Theodora Goss's Blog, page 33

July 27, 2012

Writers and Families

Writers have families.

On the one hand, this is good because it gives the writer something to write about. On the other hand, it’s bad because it means the writer is under scrutiny. Families read the writing, and they inevitably evaluate it relative to themselves. Is a story really “about” the family? Does it put forth a position with which the family disagrees? Does it represent members of the family in a negative way?

This reminds me of a former boyfriend whom I once called Raven, and who therefore imagines that every raven in every story or poem is always him. (Even the unflattering representations.)

Families are like that. And it’s probably worse when the writer is writing non-fiction, giving interviews or describing his or her life in a blog post. Everything is taken to reflect on the family.

My family has a strange attitude toward my writing, which I think is almost always the case unless the writer comes from a family of professional creators. (By professional, I mean people who actually make a portion of their incomes from a creative endeavor — writing, art, dance, etc.) When I met my cousins in Debrecen, they told me they’d heard I’d become a famous writer, of fantasy like J.R.R. Tolkien. Of course, I’m not at all a famous writer, and what I write is nothing like Tolkien. They’d never read my writing themselves — that was simply the general family impression.

My parents’ generation was raised under communism, and still retains the assumption that literature is important to the extent that it adheres to literary realism. I remember being given Earnest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea when I was a child and being told that it was great literature. Now, I like Hemingway very much, but I loathe that particular book, partly because it’s boring, and partly because I was given it as an implicit model for what writing should be like. I think becoming a writer always involves a rebellion against what and how one was told to write. My rebellion is in part against the dreariness and tedium of what I was taught as great literature.

So it’s a problem, really. Writing professionally means writing for an audience, and that means one’s writing is out there, to be judged — including by one’s family members. Who, in some way, are the group of people it is least for. Writers treat their experiences ruthlessly — witness my making fun of the way Hungarians do laundry, which got me into trouble, but surely if I can make fun of anything, it is my own country, my own people. We are not merciful, we writers. We take things apart, we put them back together.

I’m not sure what to tell writers’ families about all this. I suppose this, at least, might be reassuring: if your name is Judith and the writer creates a character named Judith, that character is not you. Not even if Judith majored in the same thing you did in college. The writer is using you to create something completely different. Of course, no one likes to be used. But at least it’s better than actually being written about. The writer transforms everything, but in doing so he or she uses the material that is at hand. This implies no particularly insight into you, the actual Judith — either good or bad.

I write this because it’s something I discussed with Catherynne Valente, while we were both in Budapest — and also because I’ve had family members reading my writing lately, and it’s frustrating to be misunderstood. But then, it’s probably frustrating to be in a writer’s family as well. After all, if the writer becomes famous (there is always that miniscule chance), the family will be remembered only relative to the writing — as Hemingway’s is. It’s rather a horrible thought, that one might be a line in someone else’s Wikipedia entry, as writer’s parents, spouses, and even children often are. I’ve always felt sorry for Christopher Milne — although he has his own entry, mostly because he wrote about being Christopher Robin.

So basically, it kind of sucks having a writer in your family. But it’s difficult for a writer as well, because people who aren’t writers or editors or publishers have a hard time understanding exactly what it is we do, how we transmute life. How even in a blog post what we present is a story, intended to be read by an audience. How even we become our own characters. (What I write here is not about the ordinary, everyday Dora, but about Theodora Goss, who has a series of adventures and insights. She is real, and she is me, but she does not represent my every thought or moment. Perhaps it might be more accurate to say that she is realish.)

It’s difficult, isn’t it? And in the face of it, what the writer has to do is go on being ruthless. Because if you don’t mine the material, if you hold back and censor yourself, which is so easy to do when you know your writing is being read, you betray your allegiance to the story. And that is where your allegiance lies. Milne may have been a bad father, Hemingway was certainly a bad husband — but they were excellent writers.

Christopher Robin Milne, with bear:

July 23, 2012

Finding Your Balance

This is going to be a short post: today is my last day in Budapest, and I have packing to do. But I was thinking about the issue of balance. When I take a ballet class, we do each exercise on both sides, right then left. After the right side, the teacher always tells us to find our balance. There we are, en pointe, letting go of the barre and finding the center of our bodies, where we can balance: figuring out how we can stay en pointe, on two legs or sometimes just one. If you don’t find your balance, you can’t turn. You can’t do a pirouette.

We have to find our balance in life as well, of course. It’s from that balanced place that we can turn and move. We each find and maintain our balance differently, I think — just as we all have different bodies, different minds and spirits. For some people, it means living in the peace and quiet of the country, having a garden, keeping chickens. For some, it means living in the liveliness and bustle of the city. For almost everyone, I think, it means finding the work you feel as though you were meant to do.

I was thinking of this particularly because yesterday I was feeling a bit off balance. My friends Cavin and Sunshine were visiting, and we spent the day walking around the city. For lunch, we stopped at Gerbaud.

If you were wondering what Gerbaud looks like from the inside, here it is. The nineteenth century did coffee houses right, didn’t it?

At Gerbaud I had an enormous, sophisticated ice cream sundae, the Gerbaud Sundae. (This is how it’s described on the website: two scoops Gerbeaud “Valrhona” cake, three scoops chocolate ice-cream, apricot purée flavoured with apricot palinka and dried apricot, whipped cream, apricot foam, chocolate sauce, Gerbeaud bonbon.) It was absolutely delicious, but of course it was too much to eat. Still, I figured, it was the last day I would be walking around Budapest, and I could do something extravagant.

And then we went to St. Stephen’s Basilica.

Before going inside, we decided to climb up to the dome and look down on the city. Now, I’m not afraid of heights, exactly. But I am afraid of falling from them. The sign at the bottom said it was 302 steps up. When we got to the top, I stayed close to the wall. I think that may be a matter of balance as well: I always feel as though I’m going to plunge to the city below, despite the stone parapet that has surrounded the dome for more than a century. But I did take some pictures.

This is a picture of the stairs going down, with bits of Sunshine, Cavin, and Ophelia (who was much braver than I was, and held my hand walking around the entire dome). The lower stairs were stone. The upper stairs were cast iron, so you got a much clearer sense of how far you had climbed.

This is my last day in Budapest, and I feel very sad to be leaving. But I think that throughout this trip, I have gotten a much better sense of my balance. It’s often by being slightly off balance that you feel where your center of balance is. You have to test and feel your limits. I hope that knowledge will help me in the next year. It will be a year of transformations — among other things, the year in which I’m trying to finish the novel. I hope I’ll be able to find my balance, to maintain the place from which I move and turn.

July 19, 2012

Missing Budapest

I wanted to write a blog post today, because I didn’t write one yesterday, but I’ve spent all my internet time responding to emails and doing my banking. (What did people do before online banking? How did they go on long vacations? I just don’t know.) So here I am, with ten minutes of wifi left, and I don’t know what to write.

I think I’ll write about what I’m thinking and feeling right now, which is how much I don’t want to leave Budapest. When I first arrived, I wasn’t all that enthusiastic about being here. I had loved London so much, and returning to Debrecen was depressing. So the first day in Budapest, all I wanted to do was go back to London. But in the next few days, I started getting used to the city, knowing where things were, realizing that I could get literally everywhere from the apartment. That I could take the metro or walk all over this city. Also, that I could function well even without a great deal of Hungarian.

This is a picture of my favorite restaurant, the Épitész Pince Étterem, which is just around the corner form the apartment. It has stood in the same spot for at least the last hundred years, I think. This is a picture of the courtyard, where Cat, Ophelia, and I usually sit when we go there.

So I’m already nostalgic: I already miss Budapest, even though I still have almost a week here. But that’s not enough. I will miss the flavors of the food, the fact that even the tomatoes from Tesco taste like actual tomatoes. It’s different to describe how food in Hungary is different, but perhaps it will make sense if I say that everything has at least one more layer than it would have in the United States. The flavors of the food are more complex. And everything tastes fresher. I will miss having a little bakery across the square, and a large market down the road. I will miss the fact that the food is smaller: the yogurt here is in smaller packaging, for example. I will miss the variety. I will especially miss the plums and sour cherries everywhere.

This is another picture of my favorite restaurant.

I’m also having a wonderful time seeing friends here. On Tuesday, the writer and editor Csilla Kleinheintz took Cat, Ophelia, and I to the Ethnographic Museum, and on Friday two friends of mine arrive from Sarajevo. We’re going to have fun showing them around the city.

I will miss being able to go all over the city by metro, but almost as soon as I get back, I move into Boston, so I will have that experience next year. I will be able to do my marketing several times a week, rather than in one large grocery shopping trip, and I will be able to get on the metro and go to the museums. I’m looking forward to being a city girl again.

Today, we have a museum visit, the dinner with Hungarian writers and editors, and then Cat’s reading. It’s been a wonderful visit. I just don’t yet want it to end.

July 17, 2012

Fearless Women

Sometimes I write bits of stories before I actually have stories for them to go into. There is something I wrote a while back in one of the notebooks I brought with me. It goes like this:

“I felt that I was the most beautiful I had ever been in my life, and the smartest and bravest. I felt as though I deserved to feel alive, as though I deserved life and love and to do the work I was meant for. And that if I was brave enough to strive for those things, the universe would help me.”

When I wrote this, I had no idea what story it would go into, but I think now I know. While I was in London, I got an idea for, not a story, but a whole novel, to be called The Malcontents. It would be about a woman, an academic, who was researching women who had not been content with the lives they were supposed to live, and so they lived other lives: women like George Sand, Virginia Woolf. They decided to live in ways they were not necessarily supposed to. And it would be about her own life, the academic’s: about how she herself became one of the malcontents. I have no idea when I’ll have time to write this novel, but I like the idea a lot.

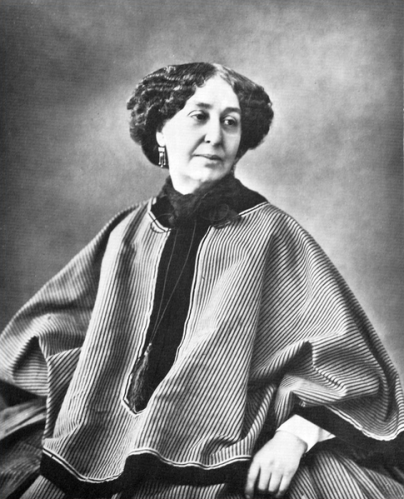

Here is George Sand:

I think there is a certain age, for women, when you become fearless. It may be a different age for every woman, I don’t know. It’s not that you stop fearing things: I’m still afraid of heights, for example. Or rather, of falling — heights aren’t the problem. But you stop fearing life itself. It’s when you become fearless in that way that you decide to live.

Perhaps it’s when you come to the realization that the point of life isn’t to be rich, or secure, or even to be loved — to be any of the things that people usually think is the point. The point of life is to live as deeply as possible, to experience fully. And that can be done in so many ways.

This is of course a personal post, because I feel as though, although I’m certainly not fearless, I have become more so in the last few years. You become fearless in part from experiencing things, from going through difficulties and setbacks. The more you do that, the more you discover that you can get through them, that you’re stronger than you thought. And suddenly, things that used to scare you aren’t so scary anymore. So I will claim for myself that I’m more fearless than I used to be.

Here is Virginia Woolf:

My internet time is about to run out. But I like this idea for a novel. I like it a lot.

July 15, 2012

The Keats House

Today I thought I would upload two pictures. Here they are:

On one of the days I was in London, I wandered around the southern and eastern parts with Lavie Tidhar. Quite by accident, as I was walking to meet him, I came upon the house that John Keats had lived in while he was studying medicine at Guy’s Hospital. The hospital is still there, and I walked around it a bit. I saw the monument to Keats (that’s the second picture). It’s a strange monument, isn’t it? Keats is sitting there alone, although you can sit on the bench next to him. I wonder how alone he was in his life? I always think of him as essentially lonely, although perhaps I’m wrong. Perhaps my impression comes from knowing that his poetry was not well-received, at first. And he died so young that there wasn’t much more than “at first,” for him.

I was thinking about this today because Ophelia and I went to visit a childhood friend of mine, who lives in the suburbs of Budapest. She followed a path that is similar to mine: she has a law degree and is doing a PhD. She’s not a writer, but the similarities made me think about my own life. What would it have been like if I had grown up in Hungary?

The suburb she lived in was lovely, with houses painted in shades of yellow, orange, and green lining streets shadowed by poplar and linden trees. It was peaceful, quiet, about a half-hour outside of Budapest but on the subway line. It had parks where children could play. And I wondered if I would be living in a Budapest suburb, or perhaps still in the city itself. What would I have studied? Would I be a writer, and if so, would I write in Hungarian? (Surely I would write in Hungarian.) Would I, when the borders opened, have left for England or another European country?

I just don’t know.

And I thought (this was the conclusion I came to) that for all its turbulence, I would not change my life. I would not choose to be anyone else, or in any other place. Everything I’ve gone through had brought me to where I am now, writing my stories. I would not trade those for anyone else’s stories.

After all, out of all of Keats’ turbulence, came this:

Bright star, would I were stedfast as thou art –

Not in lone splendour hung aloft the night

And watching, with eternal lids apart,

Like nature’s patient, sleepless Eremite,

The moving waters at their priestlike task

Of pure ablution round earth’s human shores,

Or gazing on the new soft-fallen mask

Of snow upon the mountains and the moors –

No–yet still stedfast, still unchangeable,

Pillow’d upon my fair love’s ripening breast,

To feel for ever its soft fall and swell,

Awake for ever in a sweet unrest,

Still, still to hear her tender-taken breath,

And so live ever — or else swoon to death.

July 13, 2012

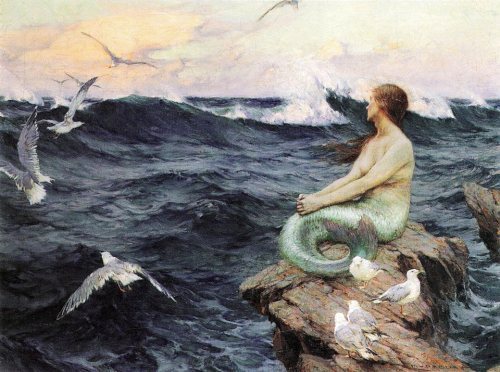

Selkie Women

I had a sort of incomplete revelation the other day about selkies.

An incomplete revelation is where I realize something, but I’m not entirely sure what I’ve realized, how it works. But I generally know what it has to do with. In this case, it has to do with the otherness of the magical animal women in folk and fairy tales. It has to do with another way of looking at them.

It occurred to me that there have always been selkie women: women who did not seem to belong to this world, because they did not fit into prevailing notions of what women were supposed to be. And if you did not fit into those notions, in some sense you weren’t a woman. Weren’t even quite human. The magical animal woman is, or can be, a metaphor for those sorts of women. Perhaps my thinking on this issue was influenced by having just read John Fowles’ The French Lieutenant’s Woman, because Sarah Woodruff is one of those women. She is presented as not quite human, which could be seen as a problem with Fowles’ characterization. Or it could be seen as something else, the fact that certain women are perceived as otherworldly, are not understood, precisely because they cannot be understood according to prevailing codes.

I had gotten an idea, too, for a book about those sorts of women, like George Sand: the women who never quite fit into their societies. Perhaps Sand isn’t the best example, because she does not strike me as particularly magical. And I’m talking about women who are seen as incomprehensible, magical, fay.

Selkie women are the women you don’t understand. They are the women who know that they belong to another tribe, in another element. And so they seem as though they don’t belong in yours — and they don’t. They are the women who live by other rules and values, because their rules and values are different from those of this world. They are the women who sometimes seem to be listening to other voices, or music you can’t hear, or the call of distant bells. There is a faraway look in their eyes.

Selkie women are the ones who look as though they came out of fairy tales, because they did. The ones who look at the sea longingly, who look at the sky as their home. They do not fear death. They only fear imprisonment.

Selkie women are the ones you can’t keep.

It is a very bad idea to hide their sealskins. They will always find them again, and then they will leave, specifically because you hid it the first time.

Selkie women are the ones who create things, but those things look as though they came from another world. Men fall in love with selkie women because they see them as conduits to something richer, stranger, more authentic. This is dangerous: wherever they came from, selkie women can’t get you there. You have to get there on your own.

There’s a story in all this, of course. I have so many other stories to write that it won’t get written for a while, and it’s still developing in my head. But now that it’s there, the idea will develop. Tonight, I need to write a rather ugly scene in my current story. That’s one reason I like writing this, about selkie women.

July 11, 2012

The British Library

Today I’m going to combine two things, the British Museum and the British Library, because I don’t have pictures from the latter. But I want to talk about what I saw there, because it was one of the most important parts of my trip to London. Here is the picture I took going up to the second floor of the British Museum.

And here’s an example of the sort of thing I found there. Once again, the collection was so incredibly rich. These were documents from the Royal Library of Nineveh.

One of my favorite items was this relief of either Inanna or Ereshkigal. I’d seen pictures of it before, but of course it was quite different to see the real thing. It was smaller, but also more powerful, than I had expected.

This is the last picture I’ll include from the museum, but you can imagine what a treasure-house it was. I must have walked through the rooms of that upper floor for two or three hours.

Later that week, I went to the British Library, specifically to see an exhibit called . The only way I can give you a sense for what the exhibit included is to list some of the items I saw there:

1. The oldest copy of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight in existence.

2. Marked proofs of Thomas Hardy’s Far from the Madding Crowd.

3. Oscar Wilde’s manuscript version of The Importance of Being Earnest.

4. An audio of an interview with Stella Gibbons about why she wrote Cold Comfort Farm. (Which I listened to rather than saw, of course.)

5. A copy of A.E. Houseman’s diary from 1891 recording the temperature and what was blooming. (It snowed on May 14th, even though the cherries were in bloom.)

6. A watercolor painting by J.R.R. Tolkien of The Hill and Hobbiton-across-the-Water.

7. George Eliot’s manuscript version of Middlemarch.

8. A copy of Household Words containing the serialized first chapter of Elizabeth Gaskell’s North and South.

9. George Orwell’s hand-drawn map of his trip while researching The Road to Wigan Pier.

10. A letter by William Wordsworth describing how he had composed Tintern Abbey.

11. Dorothy Wordsworth’s Grasmere Journal.

12. A letter John Keats wrote to his brother while on a walking tour of Scotland.

13. Emily Brontë’s Gondal Poems in manuscript.

14. Charlotte Brontë’s manuscript version of Jane Eyre, open to the page where Jane first meets Rochester.

15. William Blake’s notebook with a draft of “The Tyger.”

16. Robert Louis Stevenson’s manuscript version of Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

17. J.K. Rowling’s manuscript version of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone.

18. Angela Carter’s manuscript version of Wise Children. It was open to the first page, which begins, “Why is London like Budapest? Because it is two cities divided by a river.”

19. Jane Austen’s manuscript version of Persuasion.

20. A newspaper produced by Virginia Woolf and her siblings when they were children. (They reported on going to a lighthouse.)

21. Lewis Carroll’s manuscript verison of Alice in Wonderland, the one presented to Alice Liddell, with a drawing of the Red Queen and Alice.

22. Kenneth Graham’s manuscript version of The Wind in the Willows.

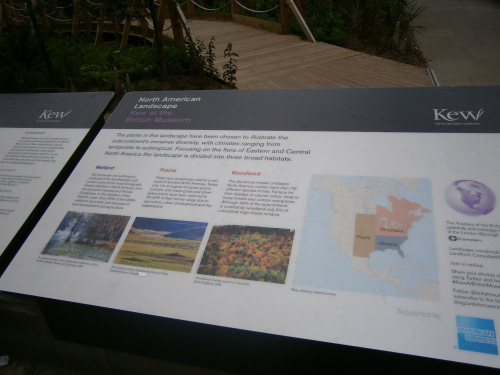

And that is a very partial list. You can imagine how slowly I walked around that room, how in places that exhibit almost brought me to tears. I’m going to end this blog post with two pictures of something I saw at the British Museum that amused me very much. It was an exhibit just outside the museum, in the garden area. It was called North American Landscape, and it included all sorts of native North American plants.

Except that they were planted very much as they would have been in an English garden. I can’t imagine any collection of native North American plants looking less like an actual North American landscape than this:

But my trips to the British Museum and Library were both wonderful beyond words. They were experiences that I will remember for the rest of my life.

July 9, 2012

The Elgin Marbles

This may be a short post, because I’m not sure how many minutes I have left on my free wifi.

First, I thought you might like to see the Elgin Marbles in the British Museum. I know the political controversy that surrounds them and their purchase by Lord Elgin, but I was glad to be able to see them in a museum, at eye level. I believe a museum is where they belong. But then, I think art is more important than nation-states. Walking through the British museum reinforced that notion: all the nations that have passed, that no longer exist! Except in their art. The art is important. Borders and national ownership are temporary.

My favorite sculpture, as you might expect, was this head of a horse. So wonderfully modeled and so expressive!

One of the most interesting parts of the museum in terms of my research was the long room in which items are displayed as they would have been in the nineteenth century: in a series of evolutionary sequences. So for example, pots were displayed to show the development of pots, evolutionarily. There is a beautiful and false logic to that sort of display and the thinking it represents. That was the subject of my doctoral dissertation, and it’s finding its way into my novel as well. About which more anon.

This was another of the really wonderful meals I had in England: just a slice of oat honey loaf and a cappuccino. The best places I found to have coffee in England were, strangely enough, the British Museum and Victorian and Albert Museum cafés. And both of them sold this delicious loaf.

I think I’ll end my post here today, because I have to run to Tesco to pick up some more food before picking up Catherynne Valente at the airport. If you’ve been following my blog, you’ll know that the two of us are here on a writing retreat. We’ll be working hard, writing and editing. But we’ll also be seeing the city.

Oh, and about the novel. I think I finally figured out how to write it. Last night, I intensively revised part of the first chapter. It’s going to be quite different than I thought it would be, more like the original novella than I expected. And I have no idea if, in this form, anyone will want to publish it. But I’ve decided that the only thing worth thinking about, when I write a story, is whether I like it, whether I want to write it, whether it excites me. The time to think about all those other considerations is afterward . . .

July 8, 2012

The British Museum

Last night, I couldn’t get to sleep. I think it was the excitement and nervousness of being in a new place, for the third time in three weeks. Or maybe it was the coffee I had yesterday. Hungarian coffee is strong!

This morning, I woke up and walked around a bit. It’s Sunday, so the city is very quiet. It feels almost empty. I ended up at the Danube, looking across the river toward the Gellert baths. Then I walked back toward the apartment and found a Tesco, so later I will be doing some marketing.

But what I feel more than anything this morning is a strange sense of sadness. I think it has to do with what I’ve been writing about: this effort to figure out who exactly I am. Because when I was in London, I felt as though I was saying hello to a city I was seeing for the first time. A far too brief hello. But here in Budapest, I feel as though I’m saying goodbye. I’m here for another two weeks, so perhaps that feeling will change. But I’ve felt this before: the sense that even though I’m in a particular place, I’m already gone.

Today, I’m going to be including some pictures I took of the British Museum, where I went on my second full day in London.

I suppose that sense comes in part from knowing, deep down, that if I’m serious about having the writing career I want, this is probably the last summer I’ll be able to do something like this: just take off and go to Europe for a month and a half, even though I am doing research while I’m here. My friends who are writers, and who have the sort of career I want, mostly travel on business. They go to conventions, or to signings, or to meet with publishers.

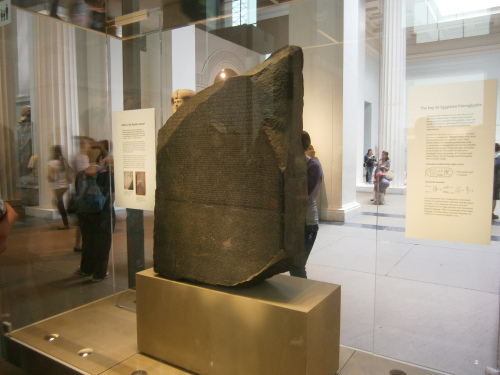

I will always love Budapest, but it feels as though it belongs to my past. Perhaps that sense will change this week? Look, the Rosetta Stone! It really is incredibly impressive, when you see the real thing up close.

And perhaps it’s a sense, too, that there are so many places in the world I want to see. If I could go anywhere next, it would be the English countryside. And then Ireland. And then Scotland. And then, perhaps, Greece.

I walked for hours through the British Museum. It’s the sort of museum that you can tackle systematically, unlike the Victorian and Albert, which I visited later that week. But I sort of ambled, looking closely only at the things I particularly loved. It’s the perfect museum to amble through.

Of course, I was in London to research the late nineteenth century, and it doesn’t seem as though these monuments would have anything to do with that period, does it? But somehow, all week, I kept ending up in places where I could learn about my era. Even in these halls, because the items in them had been collected in the nineteenth century, during the era of empire.

The English were such collectors. Of everything, really. After ambling through the British Museum, I started wondering if there were any of those red and black jars left in Greece!

One of my favorite items in the museum was this small plate, with a picture of Aphrodite riding a goose. It’s such a domestic image, somehow.

So that’s me this morning, sitting in the California Coffee Company on Múzeum Utca, in the middle of an identity crisis. But that’s not necessarily a bad thing, is it? It’s out of those moments of crisis that we learn about ourselves, even though they’re uncomfortable at the time. The thing is, I feel as though my life is shifting in deep and fundamental ways. And I hope that I can keep my balance. Or if I fall, I hope that I can get up again.

Tomorrow, more pictures of the British Museum, including the Elgin Marbles.

July 6, 2012

Kensington Gardens

On this trip, I have a secret mission. It’s to figure out who I am, now that the dissertation is done. Who I am and what I want to do, because now that the dissertation is done, I have the time to become that person, to do those things. But of course, you can’t simply decide who you are. It’s a process of discovery.

The pictures I’m going to post today are from Kensington Gardens, where I went on my first full day in London after visiting Hyde Park. The picture below is the Peter Pan statue.

If you look at it right, every experience can teach you about yourself, about who you are at the core. Because you will respond to those experiences, and you can examine your own responses. This sounds like a bit of an arduous process, I know. But I think that many people are actually mistaken about who they are. They think they are one thing and are actually another. You can live like that, but you can’t write like that. I would venture to say that all of the arts, even music and dance, require self-knowledge. And honestly, I feel as though I lost myself for a while there. It’s only been in the last two years that I’ve started finding myself again, figuring out who I am at the core. Because I think the core doesn’t change: what I am, I was at twelve, and will likely be at eighty-two.

Kensington Gardens is quite different from Hyde Park. It’s larger, more open: there are more areas of just grass and trees. I entered it by the Peter Pan statue, which is next to the Long Water, which is basically a continuation of the Serpentine. It’s a long lake with ducks, geese, all sorts of waterfowl. And then I walked along the lake until I came to one of the most beautiful parts of the park, the Italian Garden.

After walking around the Italian Garden, I left the park for just a moment and took a picture of the street. This is a picture of a London street, but quite a posh street, since it’s next to the park. Think of New York next to Central Park: that’s what it reminded me of.

But then I turned and walked through the leafy avenues of Kensington Park. It was cool and lovely under the long alleys of linden trees.

Finally, I visited Kensington Palace. I paid to go in, and at first I thought I had wasted my money (it was £15!), because the palace itself is in the process of being refurbished, and so many of the items that are usually there weren’t. But I was in luck, because instead there was a exhibit focused on the reign of Queen Victoria, who had grown up there. And I saw many things that I don’t think I would have seen otherwise: two pairs of her stockings (one for her wedding, one from when she was in mourning), her personal jewelry, a piece of Honiton lace she had worn as part of her wedding veil. So now I know what Honiton lace looks like and why it was considered so precious. It really is the most beautiful lace that I think I’ve ever seen. Here is the statue of Queen Victoria in front of Kensington Palace.

And I gained new respect for Prince Albert, seeing how much time he spent working on the Great Exhibition, how much thought he put into it. He did not have to be so enterprising; he would simply have done nothing for the rest of his life. But instead, he did a great deal for Britain and the public good. He’s become a figure of fun because the monument to him in Kensington Gardens is so extravagant, and I have to admit that it does look like a bit of Las Vegas that has landed in an English park. But I like Prince Albert.

In the café in Kensington Palace, I had what was one of the best meals I had in London, although it was so simple: a cheese sandwich with a sort of sweet relish, and a ginger beer. (Ginger beer, by the way, is nothing at all like American ginger ale.

Since I started writing this blog post, a storm has sprung up in Debrecen. I may lose my internet connection, so I’m going to post what I have now. More on finding myself in the next blog post.