Theodora Goss's Blog, page 35

June 4, 2012

The Workshop

Tonight, I am in the Slough of Despond. That’s a reference to Pilgrim’s Progress, although Christian’s slough has to do with his sins and guilt for them, and my particular slough has to do more with my complete exhaustion. This is how the slough is described in the book:

“This miry Slough is such a place as cannot be mended; it is the descent whither the scum and filth that attends conviction for sin doth continually run, and therefore is it called the Slough of Despond: for still as the sinner is awakened about his lost condition, there ariseth in his soul many fears, and doubts, and discouraging apprehensions, which all of them get together, and settle in this place; and this is the reason of the badness of this ground.”

Well, the fears and doubts and discouraging apprehensions are right on, anyway. I think I’m feeling them because I’ve been going and going and going, as though I’m some sort of automaton, and of course I’m not. Eventually, I wear myself out.

Last week, I revised the first five chapters of the novel, and this weekend I took the bus to New York so I could workshop them with my group, The Injustice League. Some of us could not make it, but Catherynne Valente, Delia Sherman, and Ellen Kushner were all there. When we workshop, we do it a little differently from most groups. Here’s what happened this time: over lunch at a Thai place, we workshopped Cat’s story, then over dessert at a coffee shop (where I had a wonderful tiramisu) we workshopped my chapters, and then finally, over dinner at a Japanese place, we workshopped Delia’s story. Each manuscript was discussed for more than an hour, and each was discussed more intensely than I’ve ever seen a manuscript discussed in any other workshop. That’s what makes this workshop so special, I think. I’ve never talked to other writers about writing at such a high level.

And the critiques were intensely useful. I now know why I’m writing this novel and what I need to do next and after that and after that. Before, I didn’t have a clear path; I have one now. I know where to go, and how to get to the next place when I don’t–when what I do know runs out. Thank you, Cat and Delia and Ellen! You are all brilliant, and I don’t think I could do this without you.

But by the time I was sitting on the bus back to Boston, I was completely exhausted–to the level where I always become an emotional mess. It’s a combination of exhaustion, sensory overload, mental distress–a sort of stew of different things that all add up to a feeling as though I’m about to break. And that’s how I felt, sitting on that bus on the way back.

So I did the logical thing, which was to text my friend Nathan Ballingrud, who had the perfect solution. He said, let’s both write a story, under 5000 words. And I said, I’m going to start now. Actually, I had already started while standing in line, waiting to get on the bus. The first few lines had come to me then. But now, I sat there with my Moleskine notebook and my pen, scribbling. By the time I arrived in Boston, I had a very rough first draft. But I knew what the story was about, and I knew that I could type it up and give it the right shape, the narrative arc it needed.

I’m going to try to type it in the next two weeks, which is the deadline Nathan and I agreed on. Then, we will exchange stories for critiquing. But the immediate lesson for me was this:

If you’re a writer, whatever your problem, the solution is always writing.

Writing a story distracted me, calmed me, made me feel as though life was worth living again. I’m still not recovered, and I suspect recovery will take another week or so. I’ve just been working too hard. But at least I feel a little better.

I wanted to find an image of a woman writing to go with this post, and you know what? There are quite a lot of them. So here is your image: Woman Writing a Letter by Gerard Ter Borch II.

June 1, 2012

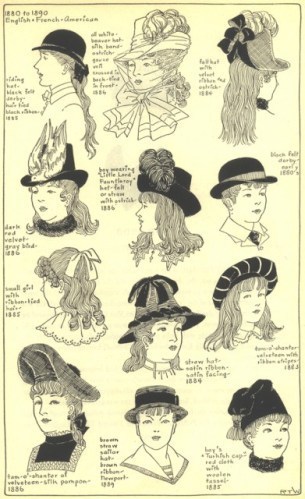

Victorian Hats

Tonight, I’m packing to go to New York, so this will be a short post with lots of pictures. Of hats.

Last night, I was up very late revising the first five chapters of The Mad Scientist’s Daughter. Around 3:00 a.m., I sent the revised manuscript to my writing group. In my email, I apologized for the roughness of the manuscript, and it really is rough at the moment: it’s at the stage where I’m still trying to get all the elements of the plot right. I’m trying to figure out the pieces of what will eventually be the central mystery of the novel. And at the same time, I’m trying to get a feel for my characters, for how they will act and interact. Since this is a historical fantasy, that includes figuring out their environment, including such seemingly mundane elements as what they wear, what rooms they go into and what furniture those rooms contain, when and what they eat. How they interact with their physical surroundings. I have to be able to imagine all those things in order to make them move through space smoothly.

In order to do that, I often have to consult research sources. Last night, for example, I was trying to figure out exactly what Mary Jekyll would look like. Here is how I started the first chapter. This may or may not be the eventual beginning of the novel.

Mary looked at herself in the hall mirror.

The face looking back was pale, with dark circles under the eyes. A halo of pale gold hair was visible under the brim of the black hat, and a high-collared black dress made the girl in the mirror look particularly sepulchral.

“What are you going to do?” Mary asked her.

“No sense talking to yourself, Miss,” said Mrs. Poole. “That’s what your poor mother started doing, toward the end. And much good it did her.”

“I doubt it did any harm,” said Mary. She turned to look at the housekeeper. “Is it still raining?”

“Yes, and you’d better take a cab or you’ll be soaked,” said Mrs. Poole. “A week it’s been, and when will it stop, I wonder? I’ve never seen London in such a foul mood. Mr. Byles about snapped my head off when I asked for chops for your dinner, and the children in the park looked as though they’d been told there would be no Christmas this year.”

There are several reasons I started this way. First, the monster looking at itself in the mirror is a classic scene. I won’t go into the whole history of the scene, but I could: Frankenstein’s monster looks at himself in a pool, Jekyll uses a cheval glass to confirm his transformation into Hyde, etc. Second, in writing workshops, you’re always told not to have characters look at themselves in mirrors, and I like breaking writing rules. Third and most importantly, it simply felt right.

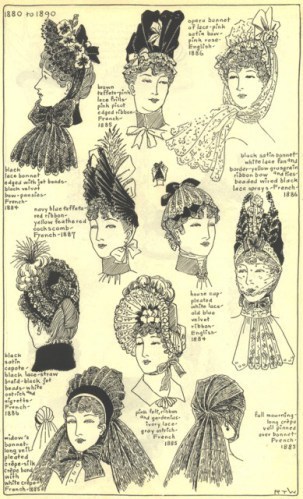

But the main issue for me was, what does Mary actually look like in this scene? Originally, I had her wearing a bonnet, but then I realized that a bonnet would have been worn earlier in the century. So I did some research, and found these pictures of late nineteenth-century hats. There were so many of them, so many different styles. I had to decide what sort of hat my character, Mary Jekyll, would wear.

They were a little earlier than the time during which my novel is set: the 1890s, when the New Woman movement became prominent. Hats became more masculine, and therefore more sensible, during those years. And Mary herself is a sensible girl. She would wear a sensible hat. But these pictures could at least give me some ideas.

The ones below were far too feminine, too fancy. Mary would never wear anything like that.

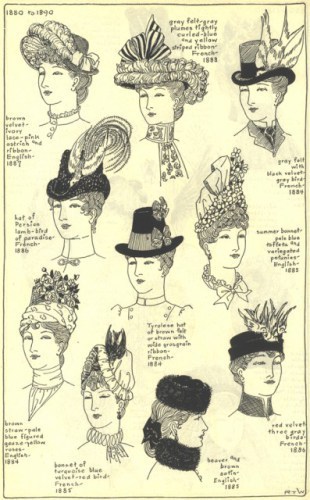

These, too, were too fancy, and far too extravagant for a girl like Mary who has no money and must make her own way in the world. In the Victorian world, financial status was almost everything (social status was everything else). And so it has to be in my novel as well, even though it’s a fantasy.

No, no, no. Seriously? Did women actually go around wearing these things?

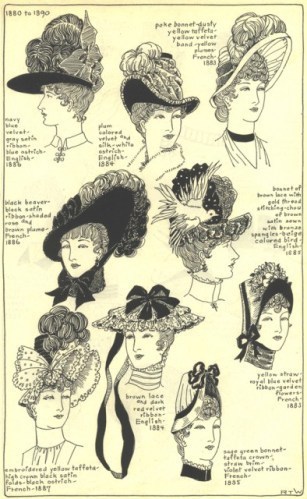

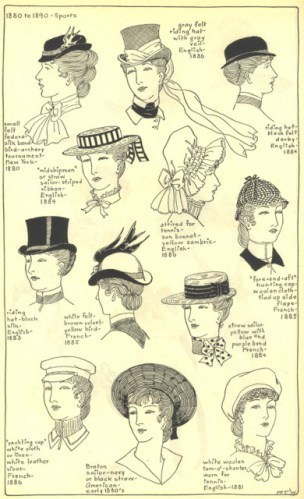

Now we were getting closer. These were hats specifically for sports, but some of them resembled the sorts of rather plain hats that Mary might wear. The one in the upper right, which looks almost like a woman’s black bowler, would fit both her pocketbook and her personality.

The last set were hats for children, and while Mary is of age, she is still young. These hats gave me a better sense of what a younger woman might wear. I decided that she was wearing something like the hat in the upper left, the black one.

The nice thing about being a writer is that you can leave so much to the reader’s imagination. So I don’t have to tell you exactly what sort of hat Mary is wearing. But it does become important later in the novel when she comes home and takes her hat off. Does she first take out a hatpin? I decided that she does not, that her hat is simple enough to just be taken off her head, and that her hair is probably in some sort of low bun that would allow her to wear a close-fitting hat. At least, that’s what I think for now. As I write the novel, I’ll get a better sense of who Mary is and what she looks like.

So there you have it, a small glimpse into what I was doing after midnight last night: revising a novel, but also looking at pictures of women’s hats from the 1880s-1900s.

May 31, 2012

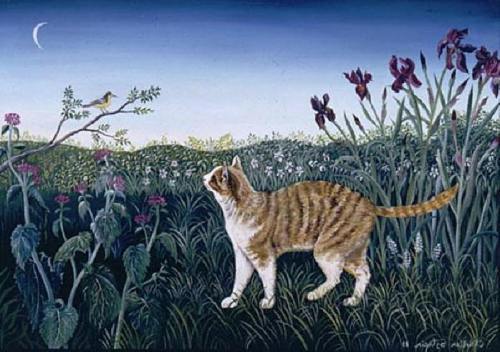

Cat Country

Daisy died this morning.

Daisy was a cat, a small gray and orange and white cat. She had come to me more than twenty years ago, when she was just a kitten, rescued from a vacant lot. She lived a long life for a cat, being her own sweet self. Everyone who saw her remarked on her eyes, where were a particularly vivid shade of green. I usually give cats fancier names (Nicholas, Cordelia). But she came to me named Daisy, and the name suited her perfect: day’s eye, a simple, familiar name.

She had been getting older, slower, visibly thinner. Had stopped grooming herself. Seeing her had reminded me of my grandmother, whom I had taken care of before she died, also of old age. It was the same process, in a person and a cat.

So this morning we went through one of the rituals of childhood: the death of a pet. I’ve had many cats in my life, and I hope it doesn’t sound callous when I say that I’m used to them dying. It’s always sad, but part of the natural cycle of our lives. And there is a great beauty in that cycle. I remember thinking, even while taking care of my grandmother, that the human body was beautiful in decay. That death itself could be beautiful rather than frightening. The experience was a revelation to me, and I thought, that’s how I want to die: peacefully, suddenly, perhaps while eating breakfast one morning.

Of course, Ophelia did not have the philosophical tools to understand it that way. She responded purely emotionally, the way I would have as a child. So I told her about Cat Country.

Cat Country is a secret, so you must not tell anyone about it. I’m only sharing it here with you, and you must only share it with friends you trust. Have you ever looked for a cat everywhere, and not been able to find it–but then seen it come out from the place you just looked? It’s not that you missed the cat. It was in Cat Country.

In Cat Country, the rivers flow with milk. The berries that grow on the bushes are chicken or salmon or lamb. the trees are perfect for climbing with claws, and their leaves are like paper, easy to chew and rip. There are birds and salamanders and mice, but no dogs of any sort. There are many insects to chase in the grass, which is particularly succulent. In Cat Country there is a castle filled with pillows, and sunlit windowsills, and dark closets to explore. It is ruled over by the Lady of Cats, who adjudicates any disputes, brushes knots out of hair.

Cats, who are magical, can go to Cat Country at any time. The one thing Cat Country does not have is human beings, so they like to come into our world for what they can’t get there: hands to pet them, laser pointers. When they die, they leave their bodies and go to Cat Country.

I told Ophelia about Cat Country, and by the end, she was telling me what she thought was there, how there were fish in the streams and entire fields of catnip. By the time we buried Daisy and marked her grave with stones, she was all right–still missing Daisy of course, but able to handle her emotional response to death. (I think that’s one thing we are responsible for teaching children–how to handle their own emotional responses. And telling stories is a wonderful way to handle, to understand and create a context for, our emotions.)

Cat Country is a fairy tale, of course, but it expresses what I deeply believe about death–that it is not an end but a transition, and that what lies on the other side is another series of adventures. I believe that nothing wonderful is ever lost, that all the things we have created still exist somewhere, even though the library of Alexandria burned and entire cities have been buried under the earth. Death happens so quickly, and the sense I have, seeing a body just after the moment of death, is that something has left–has gone elsewhere. That was the sense I had with Daisy this morning.

By now, I think she’s probably in the catnip fields . . .

May 30, 2012

Fantasy and Biography

This is going to be a short post, because I’m very, very tired today and I still have a lot of work to get done. But I wanted to write about a blog post by Damien Walter: “Fantasy Must Be a Struggle With Life.” Walter writes about a lecture by Jonathan Franzen that was reprinted in The Guardian, in which Franzen says the following:

“My conception of a novel is that it ought to be a personal struggle, a direct and total engagement with the author’s story of his or her own life. This conception, again, I take from Kafka, who, although he was never transformed into an insect, and although he never had a piece of food (an apple from his family’s table!) lodged in his flesh and rotting there, devoted his whole life as a writer to describing his personal struggle with his family, with women, with his Jewish heritage, with moral law, with his Unconscious, with his sense of guilt, and with the modern world. Kafka’s work, which grows out of the night-time dreamworld in Kafka’s brain, is more autobiographical than any realistic retelling of his daytime experiences at the office or with his family or with a prostitute could have been. What is fiction, after all, if not a kind of purposeful dreaming? The writer works to create a dream that is vivid and has meaning, so that the reader can then vividly dream it and experience meaning. And work like Kafka’s, which seems to proceed directly from dream, is therefore an exceptionally pure form of autobiography. There is an important paradox here that I would like to stress: the greater the autobiographical content of a fiction writer’s work, the smaller its superficial resemblance to the writer’s actual life. The deeper the writer digs for meaning, the more the random particulars of the writer’s life become impediments to deliberate dreaming.”

Walter writes about the two conflicting impulses that have driven his own writing. One is the impulse toward autobiography (taking materials from one’s own life):

“When I began writing I found myself tugged back and forth between two seemingly conflicted urges. One was to write about my life. My first half-dozen published stories, all now hidden on my hard drive out of public sight, were very direct explorations of the tough bits of my own life. These stories, recounting for instance the exacting details of watching my mother die of cancer, felt uncomfortably like bludgeoning an emotional response from readers. (I have the same feeling even looking back at that last sentence) In literary terms I’d had the advantage of of a traumatic childhood. I had a lot of dramatic experience to draw upon and wasn’t afraid in my early twenties to beat the shit out of people with it. In fact I enjoyed the sensation and found some needed emotional resolution in it. But I couldn’t avoid the idea that this was an unfair way to treat the reader, and I could see that this was a limited kind of writing.”

The other is the impulse toward fantasy (making stuff up):

“Fortunately, the other tug on my writing sensibilities was the urge to write fantasy. By which I mean everything from Tolkienesque high fantasy to Gibsonesque cyberpunkian sci-fi fantasy. It’s all fantasy to my way of thinking. These were the writers I’d grown up with, the imaginary worlds I had retreated in to as an escape from all that traumatic childhood stuff. But whenever I tried, or sometimes return to trying, to write fantasy as an escape, I found that what I wrote died on the page. I have half a dozen novels worth of failed fantasy that will remain locked away until and hopefully after the day I die. It all needed to be written, it has all contributed to the million words every writer must write for their apprenticeship. But none of it ever needs to be read. I can’t quite bring myself to burn/delete it all, but I could do so with no great loss.”

He concludes, “The stories I have written that pass my internal quality tests, and which I have therefore left lying around for interested people to read, have all satisfied both my urges for biography and fantasy.”

I’ve quoted so extensively from Walter here because I think his blog post states, wonderfully, what I feel when I write: those two impulses, which are not necessarily conflicting impulses for me, perhaps because my biography has been so strange anyway. So fantastical. I find that the only way I can actually write about myself, about the story of my life, is through fantasy. I’m going to link to two stories of mine that I think of as deeply personal, even though only one of them reads as personal, and both read as at least somewhat fantastical:

“The Rapid Advance of Sorrow“

“Her Mother’s Ghosts“

In a way, “Her Mother’s Ghosts” explains a bit about the more personal elements of “The Rapid Advance of Sorrow.” I also once gave a talk at an APA convention about those elements. The talk was published as an essay: “Writing My Mother’s Ghosts.” Maybe that conjunction of the biographical and fantastical is what James Patrick Kelly and John Kessel were thinking about when they reprinted “The Rapid Advance of Sorrow” in Kafkaesque: Stories Inspired by Franz Kafka.

Walter ends by saying, of Franzan’s formulation,

“Whilst it might seem counter-intuative to some, all the fantasy writing I consider truly great conforms to that conception of the novel. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings struggles with his own story of surviving the trenches of World War One. China Mieville’s Bas Lag novels struggle with his own story of living as an intellectual and marxist in one of the worlds great capitalist cities. William Gibson’s novels from Neuromancer to Zero History struggle with his own story of understanding a world reshaped by the emerging web of media he calls ‘the net.’ It’s the thing I find missing in most of the fantasy writing I encounter. However brilliantly it builds a world, tells a story, spins out remarkable idea . . . if the author isn’t engaged in the struggle with their own story, it all adds up to little more than a calcified shell, missing the fleshy pulp of life within.”

And I agree with that.

May 28, 2012

Unnatural Woman

I’m going to go back to writing about social class, really I am. But something happened yesterday that made me think, and I want to put some of that thinking down. I was testing the camera on my new BlackBerry, and I took a photo of myself. You know, the traditional photo in the bathroom mirror. It looked like this:

In the caption, I mentioned that this was a photo with no professional makeup artist or photographer, taken in harsh bathroom lighting after I’d been refinishing furniture for hours. I was making fun of myself. What surprised me was that it got quite a lot of responses, and many of them used the words “natural beauty.” Quite a few of them also mentioned that I looked just fine without makeup. Now, I had said without a professional makeup artist. Of course the woman in the picture is wearing makeup. If she weren’t, she wouldn’t look natural, because the harsh light would have washed her out completely. (And by her, I mean me, of course.) But what really caught my attention was the concept of natural beauty. It reminded me of a comment someone had once made on a photograph of mine that I had posted on Facebook. It was, “I love the red hair. I hope you are natural woman.” I’m not sure on what basis he was hoping that, because the photograph he was commenting on was heavily photoshopped. I had meant it to be edgy, not natural. Here it is, in case you’re curious:

Granted, he was probably talking about the color of my hair. But I remember my first response to the words “natural woman”: I thought, you’ve got to be joking. Because in the modern world, there is no such thing as a natural woman.

And then I thought about all the things about me that were unnatural, from my toes up to the top of my head. Even if you took the curls out of the hair (because my hair was curled that day), there would be the haircut. Hair is not naturally cut in long layers by a genius named Robert, but mine is. And you would have to remove years of the sunscreen and moisturizing creams that have made my face what it is, because faces look very different without that sort of daily care. And you would have to replace about half of the eyebrows. Also, unmanicure and unbuff the nails, unmoisturize the hands and feet. But even if you did all that, you would have to take away all the years of dance that make me stand and move the way I do, of pilates and watching what I eat that give me the shape I have. Because none of those are natural either.

Since I was a child, I have been created and constructed, as we all are. I believe in the concept of natural beauty, but I think only children have beauty that is truly natural. The rest of us are made, like mad scientists’ monsters, but in this case the mad scientists are custom and society. When they go too far, we become truly and frighteningly artificial, like certain celebrities. But when we go only as far as we need to, and people say that we have “natural beauty,” what they mean is really that we have constructed something that looks like nature the way we wish it were, nature in a dream, the way a beautifully manicured park can look like nature at her best.

I wrote in a note to myself, earlier today, “There is no such thing as a natural woman, because being a woman is performative.” But beauty is a sort of performance as well, a sort of dance that takes place over time. Women, in particular, learn the steps when they are young, as I learned it back when my mother used to tell me, “You must suffer for beauty.” (No, I’m not joking. That’s exactly what she said, and I bet all European mothers, and many American ones, say exactly the same thing!)

If there is truly natural beauty in a woman, it’s not what we think it is. It’s at the level of the bones. Shortly before she died, I visited my great-grandmother. She was almost bedridden at that point, a ninety-year-old woman with white hair haloing her face. But lying on her pillow, she was beautiful: that beauty was written into her bones, which were more prominent than they had ever been in her life. They were sharp and delicate and lovely. But that is a beauty closely allied to death. It is the opposite of the natural beauty of a child.

I’m not sure where this train of though has led me, except back to where I often end up: the idea that beauty has a necessary darkness to it, that it is allied to our mortality. Which is probably as good a place as any to stop.

May 27, 2012

More Photos

I’ve had a very busy day. Ophelia is in Virginia with her father, riding horses and finding crawfish in the creek, and I’ve been preparing for our trip to Europe. I made sure our passports were still valid, applied for a travel credit card at the bank so I wouldn’t be charged for credit card transactions, asked about the best way to exchange dollars for forints and pounds (take money out of the ATM, evidently), and tried to figure out how to get telephone service in Hungary and England. I think I’ll be taking an unlocked cell phone and buying minutes, which means I won’t have my BlackBerry (the new one, since the old one stopped working two weeks ago, taking everything with it: contacts, texts, emails). It will be difficult being without a smartphone for five weeks, but at least I’ll have my computer, and I’ll have wifi in Debrecen, London, and Budapest. The plan for Europe looks something like this: Ophelia and I will be flying Swissair to Budapest, but going almost immediately to Debrecen, where she will stay with her grandparents. I will be flying Wizzair from Debrecen to London, where I will be staying with friends for a week and doing research. Then back to Debrecen, and on to Budapest to meet the wonderful Catherynne Valente for a writer’s vacation. We will be writing in Budapest for two weeks. Then I will meet up with Ophelia and bring her back to Boston. At that point, her Hungarian will probably be better than mine!

But before any of that can happen, I have all sorts of things to do. Administrative things, first of all, but also I have to get as far into the novel as I can. My writing group meets on June 3rd, and I’ve promised them about 10,000 words. Which I have written, but not completely revised. So it’s down to New York again next weekend, but I think that will be the last trip before Budapest. I write all this to explain that since I’ve been running around today, instead of writing a blog post, I’m going to post some photographs I received last night.

Remember the photoshoot during ICFA? Well, while I was in Florida working with Walker1812 Photography, I made a list of additional photos that I particularly liked, and would like to see edited. I received some of them last night, and I thought I would post my absolute favorite, and then an example of each of the outfits we used during the photoshoot. So here you go, this is my favorite of all.

And here are examples of the three outfits.

The hardest thing about the photoshoot, for me, was overcoming my own anxiety about it. After all, I’m not a model. What I am, most days, is that geeky high school student–at least, that’s how I still think of myself, even though I look almost nothing like her anymore. I still expect to see her in the mirror. And so I think I was probably more self-conscious than I should have been. But you know what? It was so much fun! If I ever have an opportunity to do something like this again, I certainly will. And next time, I’ll be better at it.

I just have to post one more of the pictures, because this is one of my favorites as well.

Eventually, I’ll post all the photos on the press page. There are more of them coming, as well as some special projects that I’ll post once I receive them. I’m very lucky to be able to do such interesting things . . .

And now, back to work! Because I go to Europe in three weeks, and there’s still so much to get done!

Photos by Jesse Walker

May 26, 2012

Refinishing Furniture

Today I’m going to take a break from writing about social class, although I suspect this post will touch on it anyway. I want to talk about something I did today, which was refinish furniture.

It was harder than it should have been, for two reasons. First, I started by making a stupid mistake. The furniture I’m refinishing comes from two places. There’s a wooden chair that comes from Goodwill. I think it cost maybe $10? Then, there’s a wooden chest of drawers that comes from the side of the road, where a woman who was moving out of her house put it. I asked her about it, and she sold it to me, together with three armchairs, for $25. When I got them, these items were not in particularly good shape. The chair from Goodwill wobbled, and although I liked its shape, it was stained a dark color that made it seem too somber. The wobbliness was easy to fix: it just needed putty, in a place no one would look anyway, to replace some missing wood. But what to do about the dark stain? The chest of drawers was painted black to emphasize certain details, so again it was quite dark. And the armchairs? Well, imagine wooden armchairs with orange velvet upholstery. Bright orange velvet, the color of a pumpkin. And yet, like the Goodwill chair, both the chest of drawers and the armchairs had interesting shapes. There was something there – and they were solid wood, or I would not have bought them, no matter how cheap they were.

So what to do? Well, I thought I would just repaint the chair and chest of drawers a lighter color, a sort of soft white. And I would of course get the armchairs reupholstered, after painting them as well. So I started by painting the chair and chest of drawers.

As soon as I had done so, I knew I had made a mistake. I’m not sure exactly why it didn’t work – I did a perfectly fine job painting. And painted furniture is popular nowadays – it’s in all the decorating magazines. And after all, I had used the same paint on a wicker chair and a birdcage that I had bought, with great success. Maybe I just needed to get used to the painted chair and chest of drawers? That’s what I kept telling myself for about a week. At the end of that week, I knew I had to redo them. They just didn’t look right.

So that’s what I’ve been doing. I’ve been stripping the paint I put on, and it’s been an awful, awful job. Because you see, under that paint are layers of previous finish. On the chair, I think it was probably varnish. On the chest of drawers, there is a layer of paint that I suspect is an oil paint, by its goopiness, and under that another layer of something – maybe even some sort of shellac? Step #1 was paint stripper. On the chest of drawers, the two layers of paint together made what we furniture refinishers call, in technical terms, a “goopy mess.” Step #2 was Minwax Antique Furniture Refinisher, which is one of my favorite things in the world, because it really does take everything off, although you have to spend a lot of time rubbing and use a lot of paper towels.

I hadn’t refinished furniture for a long time, so there were some things I had to relearn, like the effectiveness of Minwax Furniture Refinisher. (I went through several cans of different refinishers, trying to deal with the aforementioned “goopy mess.”) Another is that when you buy gloves to refinish furniture, they must be gauntleted; otherwise, you will get small chemical burns on your arms. Small chemical burns sting like mosquito bites. They go away quickly, but I’d rather avoid mosquito bites if I can.

And what am I getting out of all this? Well, as it turns out, once I stripped the chair, I discovered lovely wood underneath. I’m not sure what it is, but it’s dark, with a close grain. And under all the paint and finish on the chest of drawers is a walnut veneer. They are going to look so much nicer when they’re done. I still have a long way to go, but I’m getting there.

There are two lessons in all this. The first is that when you take what you assume is the easy way, you often have to redo all your work anyway to get the job done properly. Second, if you buy solid wood, you can always take it back down to the core. So it doesn’t really matter if you make a mistake, because it can be fixed. But only if you buy good quality furniture in the first place, whether it costs hundreds of dollars or $25 by the side of the road.

The second lesson was taught to me over and over again, when I was a child. When I wanted to buy something that was fashionable but not of good quality, I was given the lecture again, told that something of inferior quality would not last. Furniture should be of solid wood, clothing should be of natural fibers, jewelry should be real, not imitation. And that’s pretty much the way I still live.

I’m not going to give you a picture of the furniture yet, since it’s still being worked on, but I will include a picture of a small antiques store I stopped in today, on my way to the hardware store. It’s one of my favorites, and the proprietor knows me well.

I’m leaving for Hungary in about three weeks. I want to finish the furniture by the time I leave, because once I come back things get complicated. So I have a lot of work ahead of me, but I love refinishing furniture – the hard physical labor of it. And I love seeing something beautiful emerge.

May 25, 2012

The Immigrant Class: Part 3

I’ve been trying to figure out how to describe the set of assumptions I grew up with because of my particular immigrant experience. It involved a double displacement: my mother had lost her home when she was a child (that’s what confiscated means, of course). She still remembers that house, and the pony she used to ride. She also lost her social class, because now there were supposedly no social classes, although of course that’s not what actually happened. What happened is that everyone still knew where everyone else fit in the social order, but the people who had once been peasants were now given preferential treatment – easier admission to the universities, for example. I wonder how much that really changed the social landscape of Hungary. I don’t know. But I do know that Hungarians still have an acute sense of social class. Once, I went on a skiing vacation in Austria with my father and his family. An uncle of mine was there, and I was told repeatedly that he was the one in the family who had inherited the title. Those sorts of things were not supposed to count under Communism, and yet they were always there – everyone still knew and remembered.

So I think that my mother grew up with a sort of double consciousness. She was taught that hereditary social privileges were ridiculous, outdated, and she will tell you that. Also that religion is the opiate of the masses. As is television. She believes, to her core, in hard work and individual merit. On the other hand, that core itself contains an instinctive conviction that there are certain ways to live. And those ways come from the ancient social structure that Communism was supposed to destroy.

I didn’t understand this, when I was a child. I didn’t understand why I couldn’t do the seemingly simple and innocent things that my classmates did. Wear an anklet or designer jeans. It took me years to understand that these things were about social class. I remember, as an adult, reading a column by Judith Martin, who wrote as Miss Manners. She was asked about the proper way to wear an anklet, and responded, “The proper way to wear an anklet is on your wrist, where it is called a bracelet.” I find Martin fascinating because she has a thorough understanding of the history of manners. Her knowledge goes back to Emily Post and the Victorians. And the reason I couldn’t wear an anklet or designer jeans is that, although I was an American middle school student, I was in training to be a lady. My mother would probably tell me that was ridiculous, because she was trained to regard those sorts of social designations as outdated. She would simply say I was expected to dress properly. But you know where those rules come from, what properly really means. It means properly for a particular social class.

One thing that happens in immigrant families that come from a relatively high status in their home countries is a deep anxiety that the status will lost. That children brought up in the new country will not rise to an equivalent status. Hence the focus on education, which is the easiest and most reliable way to rise up again.

I think back now to the strange disjunctions of my childhood: my mother was a doctor, but she was raising two children, so in terms of income we were nowhere near as comfortable as most of the children I went to school with. We shopped at discount stores, and I often marveled at what my friends had: the clothes, the houses with rooms just for watching TV, their own cars! On the other hand, I spent so much time at the museums that I can probably still remember my way around the National Galleries of Art, I had a favorite opera and Shakespeare play, and I knew from a young age how to behave at a symphony because I was expected (sometime compelled) to go. When my brother or I cooked, we made Kraft Macaroni and Cheese or Campbell’s Tomato Soup, but the silverware in the drawer was actual silver. The art on the walls was original art. I think I was the only person in my graduating class who applied to Harvard. I didn’t get in, and to be honest I’m not sure I would have survived it at that point. I was young and confused, and I didn’t know who I was or who I was supposed to become. I had both an inferiority and a superiority complex: inferiority because I was so obviously poorer than my classmates, which was even more true at the University of Virginia, and so much in America seemed to be based on wealth, but also superiority because I felt smarter, more cultured. And some of the things they cared about so much, I knew weren’t important.

A sort of aside here. I was taught from a young age that conspicuous display of wealth is vulgar – that it marks one as coming from a lower social class. Once, when I complained about my clothes, my mother told me with scorn that it was the children of the nobility who wore ragged clothes – that is, who wore their clothes out. They were the ones who did not display their wealth. The real problem with designer jeans wasn’t so much the expense – it was that I would have a label on my butt. And that was something one simply did not do. I still can’t bring myself to wear anything with a conspicuous label, even if I bought it for $5 at Goodwill, which is more likely than not. I like Ralph Lauren, but anything with an RL visible on it would make me intensely and instinctively uncomfortable. I think this particular standard exists because in an aristocracy, everyone already knows who everyone else is. It is only in a socially fluid society that external labels mark status. So having an external label signifies that you are a wannabe. Someone whose social status is not already fixed. Complicated, isn’t it? Of course for me, it meant that I was doomed to being permanently uncool.

One of the reasons we had art on the walls is that my grandmother was trained as an artist, so we had her art, art from friends of ours who were artists, art that my mother had collected. She was used to living with art. I’ll end today by including two paintings by my grandmother. First, a watercolor of my mother as a child.

And second, a watercolor of geraniums. I have a painting of hers rather like this in my own collection. Because of course I have a collection of art myself. Art is the one thing I have always been extravagant about.

May 24, 2012

The Immigrant Class: Part 2

I asked my mother about some of the things I had written yesterday, and she gave me some more information on my family. I thought it was quite interesting.

Evidently, I’m related to the Romantic-era Hungarian poet Dániel Berzsenyi. According to Wikipedia, “Berzsenyi was one of the most contradictory poets of Hungarian literature. He lived the life of a farmer, and wished to be close to the events of Hungarian literature. This contradiction, which he believed he could solve, made him a lonesome, introverted and bitter poet. His works show signs of classicism, sentimentalism and romanticism.” Pretty neat, hunh? When I’m in Hungary, I’ll have to find some of his poetry.

I’m also related to the nineteenth-century statesman Ferenc Deák, who was a Minister of Justice and important in the political events of the early 1800s. Evidently, “0ne of the central squares of Budapest, Deák Ferenc Square is today named after him, which is where the three lines of the Budapest Metro come together.” Also, he’s on the 20,000 forint. Here he is:

And here is a 20,000 forint:

They are both on my grandmother’s side of the family, which was the noble side. My grandfather’s father was a teacher, as I mentioned, which I assume means he had a university education. He was in World War I and came back with one leg amputated. My grandfather’s mother was a “wealthy peasant” (my mother’s words, and for her I think the term peasant has a specific meaning, because we don’t usually think of peasants as wealthy). She was the one who brought money and property into the family. My grandfather was the oldest son, and oldest sons were usually trained as agricultural engineers, which was a university degree, so they could manage the family estate. But that property was confiscated under the Communists.

Some of my grandmother’s family came from Győr, where they owned a “small palace” (my mother’s words again, because what is a small palace?). The man with the sword was my grandmother’s grandfather, and the men in that family were lawyers, judges, administrators. People in those sorts of positions all had ceremonial swords, says my mother dismissively. I’m not absolutely sure, but I think this is a picture of the specific palace:

It’s a museum now, so you can go visit. Napoleon once stayed there, and a desk he wrote on is still in the palace. I think my ancestress Katalin actually lived there.

Also, there was a physician in the family, I’m not sure on which side, who was kidnapped by a bandit and forced to tend to his wounds. Afterward, he was paid and released.

It’s all pretty romantic history, but I think many families have romantic histories of one sort or another. The more recent history is less romantic. Under Communism, my grandparents on my mother’s side lived in Budapest, in an apartment across from the National Museum. The windows look out onto the park. The apartment has two large rooms, a living room and a bedroom. My grandparents slept in the bedroom, and their two daughters slept in the living room. There was also a kitchen and a bath. In the summers, they went to Lake Balaton, to a summer house that my grandfather built himself. I think it still has no heating, and at that point I’m not sure it had electricity or gas to cook on, although it must have had running water. They cooked outdoors. They were as poor as everyone was under Communism. I don’t think my grandparents ever owned a car in their lives, although of course Budapest had a subway system and there were trains all over Hungary.

Eventually, my mother went to medical school, where she met my father. And that’s what she had when she left the country with her two children: a medical degree. That’s what allowed her to build a new life for herself in the West.

I think you could call both of my parents workaholics and overachievers. My father is an MD/PhD, a medical doctor and research scientist, faculty member at the Medical School of the University of Debrecen, and international expert on hemostasis and thrombosis (no, don’t ask me what those are). Do you think he’ll mind if I link to his official university webpage? I hope not. (I would ask him, but who knows what country he’s in today.) And then there’s my mother, who is an MD and JD, because at some point she decided that she also wanted a law degree. So she became a lawyer and patent attorney. Yeah, that’s what I came from. So you can kind of see why I ended up with a JD and PhD.

I think that’s enough for today. Tomorrow, I’ll try to write about what it was like growing up in the United States, coming from that background. You know, growing up with the assumption that at any moment, the Russians could come and take over your country. In which case you would lose everything: all that was truly yours was your education, because it was in your head. It was the one thing no one could take away.

May 23, 2012

The Immigrant Class: Part 1

About a week ago, John Scalzi wrote an interesting blog post called Straight White Male: The Lowest Difficulty Setting There Is. It was an attempt to explain the social effects of race, gender, and sexual orientation in terms of gaming metaphors. Like this:

“Imagine life here in the US – or indeed, pretty much anywhere in the Western world – is a massive role playing game, like World of Warcraft except appallingly mundane, where most quests involve the acquisition of money, cell phones and donuts, although not always at the same time. Let’s call it The Real World. You have installed The Real World on your computer and are about to start playing, but first you go to the settings tab to bind your keys, fiddle with your defaults, and choose the difficulty setting for the game. Got it?

“Okay: In the role playing game known as The Real World, ‘Straight White Male’ is the lowest difficulty setting there is.”

The post got quite a lot of attention, and some respondents suggested that John had omitted another important factor: social class. Christopher Barzak wrote a blog post on the effects of that particular factor in his own life, called Life on the Lowest Setting. I found his post fascinating because it was such a personal way to approach the subject, and I found his argument completely persuasive. He wrote,

“Class does matter. Wealth does, too, but class is an identity, an invisible identity in some cases, like mine. Many of my friends now say that they can’t imagine me having grown up on a farm, that I once took part in a 4-H contest to catch a greased pig when I was eleven, that I seem too intellectual and worldly for a background like that. They can’t put my past and my present together, because I’ve crossed over into their world, and I’ve learned their language and mannerisms, much as I learned how to speak Japanese. I can switch codes from the academic circles I work within to the circle of service industry oriented childhood friends who are waiting tables and retailing and fixing cars. And all of those features are part of my inherent personal nature, a personal nature that was nurtured in a working class environment in my formative years.

“I’d add class to that list of identity categories that determines privilege.”

I’m mentioning these two posts because I wanted to talk a bit away the way I grew up, my own awareness of social class. Unlike Chris, I’m not trying to construct an argument. I just want to put some things on virtual paper, so I can examine them myself. So I can understand myself in terms of this thing we call social class, which I have been intensely aware of since I was a child. And since I want to think about it for a while, I’ll explore it in several parts. I’m not yet sure how many.

First of all, if you’re an immigrant, you’re intensely aware of the fact that American has social classes. I think that often, native-born Americans are not as aware of class-based distinctions. Immigrants are more aware of them because many of them come from societies were social class is more overt, so they are taught to look for indicia of class. Also, when they arrive in American, they don’t belong to any social class. They have to learn the system, learn the indicia. That outsider status also makes them, and their children, more aware.

Of course, when I say “immigrant,” I’m eliding important differences between types of immigrants. My family belonged to a particular type: immigrants who were part of the educated or professional classes in their own countries and came to the United States either because of political oppression or because of a lack of opportunity in the home country. There is a commonality between immigrants of this type that can cut across boundaries of ethnicity or national origin. I have found common ground with people from India or China that may be more difficult for me to find with people who more obviously look like me – whose ancestors were European but whose families have been in this country for generations. We grew up with many of the same expectations, particularly educational expectations. We make many of the same choices.

I won’t go on much more in this blog post, but let me at least specify the sort of family background I came from, to give you some idea of what I mean by that particular immigrant class. In Hungary, my family was both educated and professional. I don’t have much information about it, in part because there are things I still haven’t been told. But here are the things I know. I know that I have an ancestress named Katalin Bezerédi, because I have a painting of her on porcelain. The Bezerédis were a prominent family in Hungary. I know that I have an ancestor who wore a sword to receive some sort of honor from the Emperor of Austria-Hungary, because my brother has the sword. I know that there is a famous poet in my family tree (although I’ll have to ask my mother who he was). Also that one of my great-grandfathers was a teacher, because I once saw his picture, looking stiff and respectable. In the black and white family photos I’ve seen from the nineteenth century, everyone looks prosperous. My grandmother’s father ran Szántódpuszta, a large farm close to Lake Balaton. It was owned by the Abbey of Tihany, and he was what my mother calls an agricultural engineer: someone trained to run such properties. It’s fun to visit, because it’s now a museum and you can walk around, seeing how people used to live in the late nineteenth century. It’s been frozen in time. My grandmother was born in this house, in the main room because it was the middle of winter and the other rooms were too cold:

She went to art school and married my grandfather, who was also an agricultural engineer. She was very proud of being a Székely, one of the Hungarian tribes in Transylvania. (I know how all of this sounds, but I’m not making any of it up. Yes, yes, Count Dracula claims to be a Székely in Stoker’s book. I love teaching that part.) The Székelys claim to be descended directly from Attila’s Huns, and sure enough, my grandmother always told me that we were descended from Attila. Remember that in Hungary he’s considered a cultural hero. She came from the lower nobility, and had the right to use some sort of crest, I’m not sure what. It’s pretty much the same story on my father’s side: there’s lower Transylvanian nobility there too. (But no counts, so don’t worry. I don’t bite.) My father’s father was a doctor, as are my father and his sister. He met my mother in medical school.

So, we’re taking about a family that came from a sort of upper professional, lower noble, financially secure class. Of course, everything changed during the Communist era. But I think I’ll write about that tomorrow.