The Immigrant Class: Part 3

I’ve been trying to figure out how to describe the set of assumptions I grew up with because of my particular immigrant experience. It involved a double displacement: my mother had lost her home when she was a child (that’s what confiscated means, of course). She still remembers that house, and the pony she used to ride. She also lost her social class, because now there were supposedly no social classes, although of course that’s not what actually happened. What happened is that everyone still knew where everyone else fit in the social order, but the people who had once been peasants were now given preferential treatment – easier admission to the universities, for example. I wonder how much that really changed the social landscape of Hungary. I don’t know. But I do know that Hungarians still have an acute sense of social class. Once, I went on a skiing vacation in Austria with my father and his family. An uncle of mine was there, and I was told repeatedly that he was the one in the family who had inherited the title. Those sorts of things were not supposed to count under Communism, and yet they were always there – everyone still knew and remembered.

So I think that my mother grew up with a sort of double consciousness. She was taught that hereditary social privileges were ridiculous, outdated, and she will tell you that. Also that religion is the opiate of the masses. As is television. She believes, to her core, in hard work and individual merit. On the other hand, that core itself contains an instinctive conviction that there are certain ways to live. And those ways come from the ancient social structure that Communism was supposed to destroy.

I didn’t understand this, when I was a child. I didn’t understand why I couldn’t do the seemingly simple and innocent things that my classmates did. Wear an anklet or designer jeans. It took me years to understand that these things were about social class. I remember, as an adult, reading a column by Judith Martin, who wrote as Miss Manners. She was asked about the proper way to wear an anklet, and responded, “The proper way to wear an anklet is on your wrist, where it is called a bracelet.” I find Martin fascinating because she has a thorough understanding of the history of manners. Her knowledge goes back to Emily Post and the Victorians. And the reason I couldn’t wear an anklet or designer jeans is that, although I was an American middle school student, I was in training to be a lady. My mother would probably tell me that was ridiculous, because she was trained to regard those sorts of social designations as outdated. She would simply say I was expected to dress properly. But you know where those rules come from, what properly really means. It means properly for a particular social class.

One thing that happens in immigrant families that come from a relatively high status in their home countries is a deep anxiety that the status will lost. That children brought up in the new country will not rise to an equivalent status. Hence the focus on education, which is the easiest and most reliable way to rise up again.

I think back now to the strange disjunctions of my childhood: my mother was a doctor, but she was raising two children, so in terms of income we were nowhere near as comfortable as most of the children I went to school with. We shopped at discount stores, and I often marveled at what my friends had: the clothes, the houses with rooms just for watching TV, their own cars! On the other hand, I spent so much time at the museums that I can probably still remember my way around the National Galleries of Art, I had a favorite opera and Shakespeare play, and I knew from a young age how to behave at a symphony because I was expected (sometime compelled) to go. When my brother or I cooked, we made Kraft Macaroni and Cheese or Campbell’s Tomato Soup, but the silverware in the drawer was actual silver. The art on the walls was original art. I think I was the only person in my graduating class who applied to Harvard. I didn’t get in, and to be honest I’m not sure I would have survived it at that point. I was young and confused, and I didn’t know who I was or who I was supposed to become. I had both an inferiority and a superiority complex: inferiority because I was so obviously poorer than my classmates, which was even more true at the University of Virginia, and so much in America seemed to be based on wealth, but also superiority because I felt smarter, more cultured. And some of the things they cared about so much, I knew weren’t important.

A sort of aside here. I was taught from a young age that conspicuous display of wealth is vulgar – that it marks one as coming from a lower social class. Once, when I complained about my clothes, my mother told me with scorn that it was the children of the nobility who wore ragged clothes – that is, who wore their clothes out. They were the ones who did not display their wealth. The real problem with designer jeans wasn’t so much the expense – it was that I would have a label on my butt. And that was something one simply did not do. I still can’t bring myself to wear anything with a conspicuous label, even if I bought it for $5 at Goodwill, which is more likely than not. I like Ralph Lauren, but anything with an RL visible on it would make me intensely and instinctively uncomfortable. I think this particular standard exists because in an aristocracy, everyone already knows who everyone else is. It is only in a socially fluid society that external labels mark status. So having an external label signifies that you are a wannabe. Someone whose social status is not already fixed. Complicated, isn’t it? Of course for me, it meant that I was doomed to being permanently uncool.

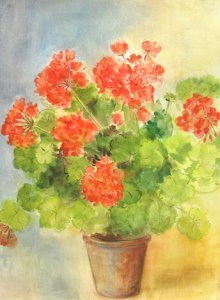

One of the reasons we had art on the walls is that my grandmother was trained as an artist, so we had her art, art from friends of ours who were artists, art that my mother had collected. She was used to living with art. I’ll end today by including two paintings by my grandmother. First, a watercolor of my mother as a child.

And second, a watercolor of geraniums. I have a painting of hers rather like this in my own collection. Because of course I have a collection of art myself. Art is the one thing I have always been extravagant about.