Theodora Goss's Blog, page 34

July 4, 2012

Being in London

I didn’t post at all while I was in London. In his preface to Lyrical Ballads, Wordsworth says, “poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility.” I think that’s true of all sorts of writing, even perhaps of blog posts. I know that while I was in London, I couldn’t write about it. I was experiencing too much every day. It’s only afterward that I can write about intense experiences, and London was an intense experience.

I’m going to write about it over the next week or so, and even post pictures, but my posts will likely be broken, fragmentary. I’m still thinking about London, still trying to put the pieces of it together. One thing being there made me realize is that my true country is the English language. That country is made up of all the books that were ever written in English, so I have Hobbiton and Wuthering Heights and the Hundred Acre Wood all in my country. And of course London.

There was so much to see there, and I knew of course that I could never see it all, so I focused on the time period in which my novel is set. I was primarily there for research, after all. I wanted to find the London of 1860-1900, and I found it everywhere. I’m going to include some pictures in these posts. The first set of pictures I will include are from Hyde Park and Kensington Gardens, where I went the first day.

The first thing I noticed about London was how easy it is to get around. I went almost everywhere by tube or on foot, although I did take the bus twice. The city felt easy, familiar, and I think that’s more than language. I think it’s because London is the city that the cities I’m most familiar with (Boston and New York) were modeled after.

I was very lucky. While I was in London, it was sunny almost every day, so I got to see the parks, which are my favorite parts of the city. I honestly don’t think anyone gardens like the English. And of course the English climate is perfect for all those flowers I would like to plant myself, such as roses and foxgloves.

I took many pictures simply of the flowers, because they were so beautiful. I will only include a few here. On my first day there, I got off the tube at Piccadilly Circus and walked down Piccadilly to Hyde Park. (You can see Hyde Park Corner in the first picture above, and then two pictures of the garden that is located right there, by the corner.) I basically just walked through Hyde Park, along the Serpentine and to Kensington Gardens.

In this post, I’ll just include pictures from Hyde Park. I’ll save Kensington Gardens for tomorrow. Of course, you know that Hyde Park is where the ladies and gentlemen would walk and ride. As I was walking along the park, I took a picture of Rotten Row (whose name is evidently a corruption of Route de Roi, the king’s way). At one point, I saw three girls, very properly equipped and on lovely Thoroughbreds, riding along that dirt track. (You can see that dirt track below, by the way. I think Dorian may have been seen riding there in The Picture of Dorian Gray? But I’d have to check.)

This is a non sequitur, but as I was walking along Piccadilly, I came upon Fortnum & Mason. Of course I had to go in. The strange thing was, as I was standing there looking around, I had one of those moments I sometimes have in which I realize that I’ve already dreamed what I am doing. I had dreamed of being in Fortnum & Mason several years before. It had looked very much the same. I don’t know, was that my brain playing tricks on me? I tend to think that time is a much stranger thing than we think it is, and that sometimes we get echoes and indications from the future. But anyway, that was the odd moment I had. Below is a picture of the Serpentine. It’s a sort of long pond, with geese and duck and swans, and if you follow it, you will end up in Kensington Gardens. Where Peter Pan used to play.

One of the realizations I had in London is that once this trip is over, I will need to retreat into myself, to close myself off from external influences to a certain extent. In order to contemplate, to gather myself together, to write. I think you can live or write, and if you’re living as intensely as I did last week, wandering everywhere, it’s very difficult to write. So that’s what I’m going to be doing over the next year. This is my summer of living intensely, a summer that’s teaching me so much. And then, I will withdraw into myself and see what I can create.

June 26, 2012

The Wedding and the Zoo

I’m sitting in the guest bedroom of a beautiful house in the north of London, looking out the window into the back garden. I think I’ll need my umbrella today. The house belongs to my friends Farah Mendlesohn and Edward James. I arrived here on Monday, and yesterday I spent the day walking around Hyde Park and Kensington Gardens. But before I get into describing what I’m doing in England, I should finish describing what I did in Debrecen.

I mentioned that Ophelia and I went to a traditional Hungarian wedding. Really, it was more a modern Hungarian wedding incorporating traditional elements. It was very long, about twelve hours from start to finish. It included a lunch, a religious wedding ceremony in a church, a civil ceremony at a sort of hotel/spa in a forest, and a dinner at that hotel. I’ll post just a few pictures from the wedding.

Of course I hadn’t come prepared to go to a wedding, so I was scrambling for an acceptable outfit. I ended up wearing a long silk skirt that my father’s wife had given me and a black silk blouse that I had bought long ago at Goodwill. I thought the outfit had a sort of boho vibe, and at any rate it was cool and comfortable. (This picture was taken by Ophelia.)

At the lunch before the wedding, the groom came and ceremonially asked for the hand of the bride. He was offered two other girls first, before he got the the one he wanted. The whole event was presided over by a man who would announce what was happening next and tell everyone where to go. He was the only one dressed in a version of traditional Hungarian garb.

Everyone else was dressed the way guests dress at the American equivalent, which would be a rural summer wedding in the south, perhaps in a city like Richmond. If you imagine how a variety of guests, about two hundred of them, of all ages, would dress at a southern wedding — well, that was how this wedding looked as well. At the lunch, there was a gypsy band.

My favorite part, I have to admit, were the deserts. They were the most traditionally Hungarian parts of the menu (the rest of the menu was rather like banquet food at every wedding I’ve been to). I didn’t get a picture of the dessert table before it was ravaged by hungry hordes, but here’s what was left.

That was just the lunch. Ophelia and I were too tired to make the religious ceremony, so we slept for a while, then rejoined everyone for dinner in the forest. What it made me realize, interestingly enough, is that weddings are the same the world over. The bride in white, a large dinner to celebrate, dancing afterward with a disco ball danging overhead, and a Hungarian band singing “Hopelessly Devoted to You” (yes, the Olivia Newton-John song from Greece). I wonder what Marcel Mauss would think of that?

The next day, my father took me and Ophelia to the Debrecen zoo. It was interesting to see what was still very much an old-fashioned zoo, mostly unaffected by the more modern concern with conservation of species. It was very much what zoos were like in the nineteenth century. There was a tiger, but also a cage of fancy pigeons particularly associated with Debrecen. The focus was still on the display of animals, and there were certain animals you could feed. Ophelia fed the llamas and ostriches.

The strangest sight for me was seeing three Canadian Geese. They have such plaintive honks, and they honked at me as though trying to make the point that they should be in the skies above Boston, not in a zoo in Debrecen. And I have to say, I rather agree with them.

The next morning, my father drove me to the Debrecen airport, which has been open only two months. It’s a converted Russian airforce base, and rather looks like it. Only one airline flies out of it (Wizzair), and going through it took me back about twenty years, to when the Budapest airport was much less international. Back then, people would look at you curiously if you were traveling with an American passport, and I got those looks that morning, although I never get them anymore in Budapest. The plane was filled with Hungarians going to London, mostly to jobs there. A man started talking to me and turned out to be a doctor, a former student of my father’s who was now an oncologist in London. It paid so much better than work in Hungary, he told me.

That concludes my stay in Debrecen, at least for now. I landed at Luton to the north of London, then took the train to St. Pancras station. And since then I’ve been here. But more on that soon.

June 23, 2012

Ordinary Life

I like seeing the ordinary life of a country. Today was an ordinary sort of day, except for the wedding, about which more later. So I’ll describe the ordinary things we did. (I write this thinking of friends who may never see the ordinary life of a country like Hungary. What I wish them is the adventure of the ordinary. Because after all, that’s where the writing comes from: from jars of linden-flower honey at a farmer’s market, and sausages hanging from a rack in the grocery store, and the graffiti on the sides of everything, even the university. From the realization that weddings are the same the world over, and that even in rural Hungary, the bride will wear an imitation of Kate Middleton’s dress, and the Hungarian band will sing “Hopelessly Devoted to You.” From the taste of pogacsa and the intermingled smells of lavender and sheep.) So, to the ordinary.

Let’s start with laundry. I’ve never seen a clothes dryer in Hungary. When I mention clothes dryers, I am met with a look of scorn, as though clothes dryers were some sort of decadent American luxury. So this morning I picked up my clothes from the porch, where they had been drying in the sun.

Now, don’t get me wrong. I am adamantly pro-clothes dryer, and have been since the last time I was in Hungary. Clothes dried in the sun do not actually smell like anything except fabric softener, because if you don’t use that, they get very stiff. And the main problem is that they don’t shrink back to their proper sizes. So your jeans don’t go back to fitting properly. But that’s part of the ordinary: in every Hungarian household, you can see clothes-drying racks. And I will admit that they are more environmentally friendly. Like other Europeans, Hungarians are environmentally-minded. If you don’t bring a bag to the grocery store, you’re out of luck.

(In the interest of full disclosure, I should state that the house I’m staying in would be considered relatively luxurious even for an American house: there is an indoor pool. But no clothes dryer.)

Meanwhile, Ophelia was watching Hungarian cartoons on the television and laughing uproariously. Notice that the channel is Nickelodeon.

When we’re in Hungary, we have Hungarian breakfasts. Here was mine: bread, cheese, and sour cherry juice. It’s no use trying to replicate an American breakfast in Hungary. The cereals taste completely different, and the orange juice is nowhere near as good, whereas the peach, pear, and sour cherry juices are excellent.

The first order of the day was marketing. We started at the farmer’s market, where there was a large variety of stalls, mostly selling local produce. I liked seeing the currents and gooseberries, since those are things one can rarely, and only expensively, buy in the United States. But there were also places where one could buy eggs, dairy products, even meats.

And then it was on to the grocery store. Did you know that there’s a brand of bottled water named after me? Well, now you do!

This particular grocery store really was a supermarket, in that it had everything an American supermarket would have and more. Food, detergents and cleaning supplies, even some clothes. But I bet your American supermarket doesn’t have a rack for sausages and salamis!

It’s late, so that’s it for today. Tomorrow, I’ll try to write about what we did in the afternoon, which was attend a Hungarian wedding. (Yes, the bride wore an imitation of Kate Middleton’s dress, and the Hungarian band sang “Hopelessly Devoted to You.” And there was pogacsa.)

June 22, 2012

Seeing vs. Staying

I think there are two ways to experience a foreign country. One is to see it: to go through in a week or less, seeing all the important sights. You can experience a great deal that way, but to be honest, I’ve never particularly liked it myself. It gives you a superficial sense of what that country is about. You’ve “done” Rome or Paris or London. And your sense of that country is largely of the past: you rush through the Acropolis without getting any sense of modern Greece. The other way is to stay for a while, to live the life of that country. That’s what my family has always done, although I have to admit it’s been because staying is cheaper rather than by conscious choice. It’s cheaper to live in a place for a while, to stay in a rented apartment or with friends.

That’s what we’re doing on this strip, a lot of staying. Right now we’re staying in Debrecen, and instead of a hotel meal, I’ve just had a breakfast of fresh yogurt made by a local grocery store, with strawberries in it. I’m going to be staying in London as well, although that trip will involve a lot more going around to see the sights. But I have friends I’ll be meeting up with, so I’ll get a sense of the place, of how people live and move around there now, rather than rushing from Buckingham Palace to Herrods to wherever else I might go.

I thought I would post some pictures from last night, when we went out to dinner at a restaurant in Debrecen. I had something called Hussar Soup. I should have written down its name in Hungarian, but I’m afraid I forgot to. I’ll try to remember next time.

The hotel even displayed the uniforms of the hussars that the soup had been made out of! Actually, it was a sort of oxtail soup. The oxtail was served separately, with the best horseradish I have ever tasted. The soup was a delicious broth with dumplings and vegetables, and you could add the meat or eat it separately. But the uniforms are in fact the real uniforms of two different Hussar regiments.

For dinner, I had something called Túrógombóc, which is a kind of cheese and semolina dumpling. What I like about the desserts in Hungary is that they’re not too sweet. The Hungarians do not have a Death by Chocolate. (I would much prefer Death by Dobos Torte anyway.) But these dumplings tasted light and delicious, while not being at all light really. My goal in Hungary is simply not to gain weight.

At least in Budapest I’ll be walking a lot. Here in Debrecen, I’m out in a small village, separated from Debrecen itself by forest and fields, and there isn’t anywhere to walk. It’s the hazard of the suburbs, which I know so well from the United States. There’s something I have to confess here: I think that food in Hungary, including the food you find in the grocery stores, simply tastes better than food back home. After dinner, we did go walking for a while, through downtown Debrecen.

It was getting dark, but I took pictures of the main square and the protestant church. Hungarian buildings are often painted these interesting, distinctive colors. They are almost Van Gogh colors. I think the Impressionists would have loved them. It’s rather wonderful to have a church this large painted a sort of canary yellow.

You can’t see the color very well here, I’m afraid, because I took the picture at twilight. In the square itself, there was a girl singing Hungarian folk songs. She was young, around twelve or fourteen, but she had a strong voice, and she sang with that distinctive, almost harsh intonation that Eastern European folk songs tend to have.

And those are all the pictures I have for today. Tomorrow, the adventure continues. But it’s the adventure of living in a place, rather than simply seeing it. I think that teaches you so much more.

June 21, 2012

The Adventure Begins

I haven’t been very good about posting on this blog because I’ve been preparing for the trip to Hungary. And now here I am, sitting at a desk in Debrecen, writing this update. It’s Thursday. On Monday, Ophelia and I took a SwissAir flight to Zurich, arriving Tuesday morning, and then another SwissAir flight to Budapest, arriving Tuesday afternoon. Budapest has a small airport: you still walk off the plane and over the tarmac, as I did years ago, the first time I came to Hungary as a teenager. But that was back in the communist era. There were almost no planes flying in, the airport was patrolled by soldiers with Kalashnikovs, and I had to pass through passport control. This time, passport control happened in Zurich, and it consisted of a quick glance at our passports and a quick stamp. Then we drove to Budapest so that I could pick up the key to my grandmother’s apartment. I checked to see if I could still get wifi at the California Café down the street, and I could. I bought a drink there that turned out to be watermelon lemonade, then sat at one of the small tables with my computer. On both sides of me, people were speaking English. I think California Café is one of the places where the Americans and Australians, in particular, gather. And then we drove to Debrecen.

It was a very long day, and I’ve been adjusting to the six-hour time difference. So here I am in Debrecen, where it’s almost ten o’clock although my computer is still on Boston time and tells me that it’s almost four in the afternoon. I’ve been asked to post pictures, so I’ll post them here and tell you what they are. The first picture is of my father’s house on the outskirts of Debrecen. This is where I am staying.

It’s located on a charming little street. This is a street of new houses, but it looks very much like Hungarian streets everywhere in that the houses, whether old or new, are surrounded by gardens. Everyone seems to garden, to grow both flowers and vegetables. One of the strangest things to me, living in the United States, is seeing the broad green lawns in the suburbs, with no gardens in them. Why not? I suppose it’s a cultural difference and has to do in part with the value placed here on fresh fruit and vegetables. Hungarians really care about their food.

Behind the house, there is a traditional Hungarian outdoor oven. We cooked in it the last time I was here, three years ago. I think we cooked a very traditional Hungarian dish: pizza. But this time, so far, I really have had very Hungarian foods. The first night, we went out to a restaurant and I had stuffed cabbage. Since then it’s been dishes like Lecsó, which has meat and tomatoes and peppers, and plenty of paprika, and I’ve had bread with cheese, and a cake made with sweet and sour cherries. Those sorts of things.

This morning, I was woken by a flock of sheet in the field behind the back garden. They were black sheep, with long, twisting horns. I tried to take a closer picture of them, but as I came too close, they moved away.

In the garden itself, the lavender is in bloom, which gives you a sense of the climate here: I see flowers growing that in the United States grow in California. But this landscape is more lush and fertile. There is more rainfall, so the flowers run riot (the roses are particularly beautiful), and the streets are lined with willows and linden trees. I can smell the linden flowers everywhere I go.

These, in case you’re not familiar with them, are linden flowers. They have a strong scent that, once smelled, is never forgotten I think. If you’ve read much nineteenth-century British literature, you’ve no doubt come across references to avenues of limes. Well, those aren’t trees growing the green fruit we think of as limes, which would never survive in England. They’re linden trees, also called limes.

Each of these photos has taken a long time to upload, because although I do have a good internet connection here, it’s not as fast as I’m used to. So in the meantime, I’ve been revising the poetry collection manuscript. There is still plenty of work for me to do here, and I’m trying to do it, although I’m also going around looking at black sheep and linden trees.

June 12, 2012

My Itinerary

Here is my itinerary for the European trip:

On the night of June 18th, I fly to Budapest. I will be flying overnight and arriving on the 19th. Then, I think I will be going almost directly to Debrecen. I will spend a week in Debrecen, then fly to London on June 25th, where I will stay with friends. In London I’m going to be spending most of my time doing research, but if you would like to contact me while I’m there, I may have time for coffee or whatever it is one drinks in England. Is it too much of a cliché to meet for tea?

On July 4th, I will return from London to Debrecen, and spend a few days there. But I need to be in Budapest by the 8th, I think, because Catherynne Valente and I have two weeks of writing scheduled. We will be writing and hanging out in cafés. However, if you are in Budapest and want to meet up, let me know. In Budapest, it will definitely be coffee. The apartment where we’ll be staying is close to the Hungarian National Museum, in Pest. It’s within walking distance of Váci Utca, which is the main shopping district. I remember being able to walk down to the Danube.

There’s one place I know I’m definitely going, which is Gerbaud. This is a slice of Dobos Torte from Gerbaud. It is the definitive Dobos Torte: you can tell because it’s the one featured on Wikipedia.

Gerbaud is only a few blocks from the apartment. Who knows, I may walk there every day simply for exercise! And then, on July 24th, I’ll be flying back from Budapest to Boston. So, this is what it looks like:

June 18th Boston to Budapest to Debrecen

June 25th Debrecen to London

July 4th London to Debrecen

By July 8th Debrecen to Budapest

July 24th Budapest to Boston

And there may be some traveling around Hungary during those two weeks in Budapest. I learned something interesting today. I have a porcelain brooch with a painting of an ancestress of mine on it. What I learned is that there’s a picture of the brooch at Bezerédj Castle, where she lived. And I have the original. Here is a picture of it:

And here is the castle where she lived:

It would be interesting to go visit, don’t you think?

All of this does mean that I won’t be able to go to Readercon this year, for the first time in about seven years, I think. I’m very sorry about that! I know there are people who were looking forward to seeing me there, and I was certainly looking forward to seeing them. I tried to find a way to come back for the convention specifically, but it was just too expensive. And my schedule was constrained by the need to go to London as early in summer as I could, to avoid the Olympics. I’m hoping that in the future, I can find a way to both go to Europe to write during the summer, and make Readercon, which is after all one of my favorite conventions.

So there you have it, that’s my itinerary. If you want to meet up with me at any point along the way, let me know! I may be able to manage it. (But if you offer to buy me anything at Gerbaud, I can pretty much guarantee that I’ll be there.)

June 11, 2012

The Immigrant Class: Part 5

Several days ago, a woman whose daughter plays with Ophelia told me that she would be moving to Jordan for a year, with the children, while her husband stayed in the United States. He was from Jordan, she was from Australia, and they wanted the children to be familiar with his culture as well. I mention this because what I’ve been calling the immigrant class could also, perhaps more accurately, be called an international intellectual class. (Remember that I’m not talking about all immigrants, but specifically those who were highly educated in their own countries. They generally come to the United States for career opportunities, but want to maintain ties to their own cultures — unless they are fleeing repressive regimes, as I suppose we were.) The international immigrant class does things like that — their children are raised all over the world, in part so they will develop the habits and expectations that come from belonging to that class. Even my brother and I were sent to Europe regularly, although my family did not have much money while I was growing up. But being international — rather than provincial, which was one of the worst things my mother could call you — was a requirement.

But I was talking about going to the University of Virginia and encountering class differences there. And there were wide class differences, because it was a state school and therefore relatively inexpensive. Good students from small towns in southern Virginia would go there, as well as the sons and daughters of wealthy lawyers from Richmond. And of course, because it had an international reputations, there were also students from places like New York and Los Angeles. You know what class they belonged to — only the children of the wealthy went to a state school for which they would have to pay out-of-state tuition.

The university had its own upper class, made up of students who were in the University Guides, who were Resident Assistants, who were admitted to the Jefferson Society. Being editor of the school newspaper counted. Some of them eventually ended up residents of the Lawn. You could tell who those were because they proudly walked around the Lawn in their bathrobes in the morning. Their bathrooms were behind the Lawn rooms, so they had to walk outside to get to them. But, on the other hand, they were on Mr. Jefferson’s Lawn — and their rooms had fireplaces. (I know all this because I dated a Lawn resident. I dated a lot of people, in those days.)

In a way, it was funny — because it could be so pretentious. There was a whole other side of the university as well, the side that I think the professors saw, in which UVA was a major research university. But among the students, in these groups, the old traditions lived on. I’m sure they live on at other universities that pride themselves on being serious research institutions — after all, Princeton still has its secret societies. (So, of course, does UVA, and belonging to one of them put you at the very highest social level.)

At the time, I was intimidated by it all. It was only later that I learned about a crucial class distinction between what I will call the provincial upper class and the actual American upper class. I met the provincial upper class while I was working for law firms in Richmond. I heard law firm partners talking at length about the country club, about their daughters’ debuts. And I realized that they were palely imitating what the actual American upper class, which did not live in places like Richmond, had done for the last century. The actual American upper class lives in places like New York and Boston — or lived, because those class hierarchies are in fact breaking apart. They are listed in actual society registers. And what I had gone to school with, at UVA, were the sons and daughters of the provincial upper class, which is important in places like Richmond, or Savannah, or Atlanta, and completely unimportant anywhere else. (If you meet members of that class, nod and smile, listen politely, and get away to somewhere more interesting as quickly as you can. The truth is that, in our international world, they no longer have much power, except at a purely local level. The people who are changing our world do not belong to country clubs.)

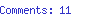

My image for the day is of the University of Virginia rotunda as it looks now:

The Rotunda itself, the physical structure, is not the cliché that you see in photographs. I used to walk around it at night, on dates with guys from the college or law school. It is a graceful building, with lovely old bricks. That was one of the reasons I went to UVA — to experience the sense of peace that only something old and graceful can provide.

June 10, 2012

Writing the Story

I’m going to try very hard to keep my blog posts to around 500 words, because I’m working on a short story. I’m writing around 1000 words a day, and in order to keep that up, I can’t spend a lot of time writing other things. Because the writing does tire me out, after a while. I know there are people who write thousands of words a day, but I find that after a while, if I’m too tired, my words are no good. And it doesn’t make sense to sit there producing writing that isn’t good. Instead, I know that I need to get out, clear my head — go to the coffee shop, buy myself a vanilla latte, walk to the top of the hill, and sit there drinking it, thinking about the story, or just anything at all.

Once I finish the short story, I’m going back to the novel, and at that point I’m going to try to write more per diem, although I don’t know if I’ll be able to — we’ll see. The novel will be more difficult, because I can usually write a short story in three drafts at most, and I’m quite sure I won’t be able to do that with this novel. I think it will take extensive revisions. Each chapter I write teaches me more about the characters, about who they are and how they respond to the world. Which of course means going back and revising the beginning.

All this is to say that I want to keep up blogging, but I’m going to try to confine myself to around 500 words, and here I’ve taken around 250 already to explain myself.

So let me tell me about what I did yesterday. I typed in the morning, then felt as though I couldn’t type anymore. I needed to get out. So I went to the coffee shop, bought myself a vanilla latte, and walked to a small park where there were benches. There, I sat on a bench and wrote the scene in which my main character betrays her lover to the secret police. Here is my Moleskine notebook with part of the scene I was writing.

As I was writing the scene, two bunnies came out and hopped around, nibbling the grass. They looked at me as though to say, “Hello. We are adorable. Are you noticing our adorableness?” So I sat there for a while, distracted, watching the bunnies. I was surprised at how close they got to me, but I suppose that’s what happens when wildlife is not at all frightened of human beings. It was rather lovely.

And here is the writer, not writing her scene, and instead watching bunnies. I’m worry to write that directly after this experience of adorable lapinity, she went back to writing the scene in which her main character sends her lover to a concentration camp. In real life, writers are gentle, harmless, eccentric creatures. But inside their heads, they are assassins. Their cruelty knows no bounds. They are capable of destroying the world. Really, I don’t know why we put up with them!

I am already over my 500 words, so I will leave you with a videotape I made of the bunnies on my cell phone. I wanted to experiment with the video function, and also to see if I could then upload the video. So I have produced what is probably the most soporific video on youtube. But there you go.

[image error]

June 8, 2012

The Immigrant Class: Part 4

This is going to be a short post, because I’m so very tired. I’ve been working all day, and I’ve spent the last two hours typing a thousand words of “England under the White Witch,” the story I drafted on the bus from New York to Boston. But I thought I would talk a bit more about social class, because I do have more to say.

I think I’ve seen a fairly broad range of the social classes this country has to offer. I haven’t seen the bottom or top of the range intimately, but I have at least seen it: the truly poor, whether the urban homeless or the rural poor living in run-down houses, and the ridiculously wealthy. I’ve met a billionaire: Jan Stenbeck, a Swedish media mogul who was mentioned in that crime novel — The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. He died several years ago, but while I was working as a corporate lawyer, he was a client of one of the firms I worked for. The firm flew me down to New York regularly to meet with the heads of his companies. We were doing some sort of corporate restructuring, I remember. But most of the people I’ve known and spent my time with belong in what we like to think of as the middle class, although in America the middle class goes all the way from teacher’s aids to law firm partners. You can be earning $20,000 a year or $200,000 a year. And the bottom and top of that class are as alien to each other as they are to other classes, I sometimes think.

I still remember going to the University of Virginia, my freshman year (although it’s called first year, there), and realizing that I was in a completely different social world. I had gone to high school in the suburbs of Washington, D.C., among children whose parents belonged to the broad middle of the middle class. Some of them were government employees who could not afford to live in the city. Some were people who serviced the new suburban economy: construction workers, librarians, restaurant managers. The suburbs had been built up in the last twenty or so years, and there were still fields with horses in them, or actually being farmed. My high school was surrounded by fields. This was a culture shock for me: I had grown up in Budapest, Brussels, and the area around the National Institutes of Health, all of which were more dense, urban, cultured. I didn’t quite know what to do with myself in these new suburbs.

One way social class differences are enforced even during the teenage years is by tracking in the high schools. I was on the advanced academic track, in the gifted program. But there were kids who left in the middle of the day for vocational training. This was the American high school as depicted in so many movies from the 1980s, where football players, cheerleaders, and prom are all important. Where students don’t necessarily go on to college. I, of course, was expected to go to college and then graduate school. But it was a strange atmosphere to be in, where students had such different expectations. My graduating class was not particularly small, several hundred students, but there were only about thirty of us tracked at our level, all taking the same sequence of honors courses. In a sense, we formed a small school within the school. Need I add that we were of course the nerds of the school? The top of the class was drawn from our ranks.

Going to UVA meant encountering a very different social class: kids who had gone to private schools, who recognized each other’s private schools, whose families often knew each other. This was the top of the “middle class” and bottom of the “upper class,” which the broad middle middle class doesn’t truly know or understand. These were the kids who, when they graduated, had internships waiting for them at Sotheby’s or in congressional offices. I think it will take an entirely different blog post to talk about the social structure of UVA, but it involved certain clubs and secret societies — partly because UVA emulated and believed itself equal to the northern Ivies. I saw this social structure from the fringes because I dated some boys from it — my college boyfriend, whom I dated for two years, had gone to Groton, as had his father before him, and he understood that structure while despising it heartily. But he could not escape it either, and walked around campus in the same uniform of untucked button-down oxfords, khakis, and what we called boat shoes — Sperry top-siders. When something more formal was required, he threw a jacket over the oxford shirt. I don’t think he ever tucked it in.

Although I’m so tired, this has been surprisingly easy to write. I think it’s because when you’re outside a social structure, it’s easier to see inside it, to note its small details. Because it was all in the small details. And to understand the nuances that determine how people are placed, and drive how they behave. More on this to come.

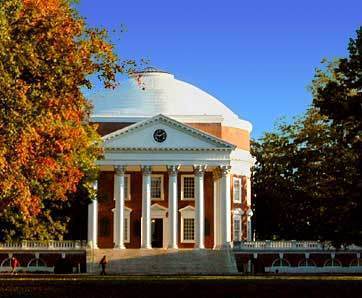

My image for to day is the UVA Rotunda, from the 1870s:

There’s one thing I should be more specific about. I went to such a variety of schools that it’s not quite fair to talk about one high school as being mine. I started school in Brussels; then went to a private Catholic school in Pennsylvania; then a small public school, and then a larger public school, in Maryland; and then H.B. Woodlawn in Virginia, which is one of the best purblic schools in the country (and can best be described as hippie alternative); then a suburban middle school when my mother decided that we needed to be in surburbs (in part because I had been followed and almost attacked by a man while walking home from the bus stop); then a large and rather frightening high school in California; then the high school I described above. The longest I went to any one school was three and a half years. After that, I went to college — which was a relief. But more on that another time.

June 6, 2012

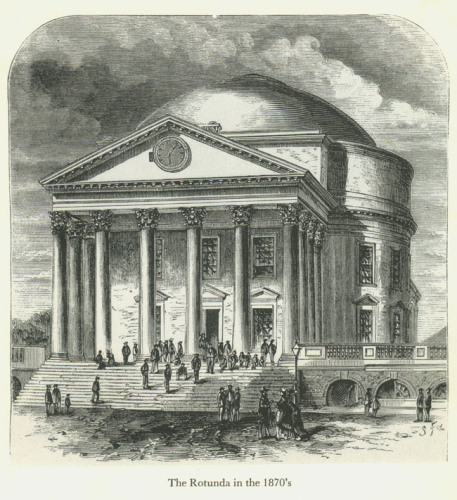

Ray Bradbury

This morning, it was all over the news and social media: Ray Bradbury had died. Can something be a shock without being a surprise? This afternoon, I found his book on writing, Zen in the Art of Writing, which had somehow gotten into a pile of other books, about five books down, even though I was in the middle of reading it, on p. 59 to be exact. I think I’m going to finish it now.

But it’s a bit superfluous, because for me at least, Bradbury is one of those writers I absorbed into my DNA — I think because of the poetry with which he wrote the fantastic. I was lucky enough to grow up on writers of the fantastic who were also poets (Bradbury and Ursula Le Guin among them), so I never thought there was one particular way to write science fiction and fantasy. I always thought one should have literary aspirations.

I’m not even sure, now, what I read by Bradbury: Farenheit 451, of course; The Martian Chronicles; a whole bunch of short stories. I read him knowing that in his writing I would find a particular mixture of poetry and seriousness. He was at once in deadly earnest and intensely playful. His death reminds me of a poem by Stephen Spender, “I Continually Think of Those.” It goes like this:

I think continually of those who were truly great.

Who, from the womb, remembered the soul’s history

Through corridors of light where the hours are suns,

Endless and singing. Whose lovely ambition

Was that their lips, still touched with fire,

Should tell of the spirit clothed from head to foot in song.

And who hoarded from the spring branches

The desires falling across their bodies like blossoms.

What is precious is never to forget

The delight of the blood drawn from ancient springs

Breaking through rocks in worlds before our earth;

Never to deny its pleasure in the simple morning light,

Nor its grave evening demand for love;

Never to allow gradually the traffic to smother

With noise and fog the flowering of the spirit.

Near the snow, near the sun, in the highest fields

See how these names are fêted by the waving grass,

And by the streamers of white cloud,

And whispers of wind in the listening sky;

The names of those who in their lives fought for life,

Who wore at their hearts the fire’s center.

Born of the sun, they traveled a short while towards the sun,

And left the vivid air signed with their honor.

Bradbury was one of those who were truly great, who remembered the soul’s history. I still remember the conclusion of Farenheit 451, of people gathered around a fire in the darkness — people who are also bits of literature, who carry in them our human and cultural heritage. That is, in a sense, an image for what we should all be. We should all carry in ourselves the highest, the best, that we as human beings can produce. We should participate in it, absorb it into us. And if we are fortunate enough to be able to, create out of it.

So often, I am so tired. But I would like to be one of those who fought for life, the life of the spirit — who wore at their hearts the fire’s center. I suppose the height and purpose of human life is to try.

Here is what Bradbury himself said about writing, and it really can’t be said any better:

“And what, you ask, does writing teach us?

“First and foremost, it reminds us that we are alive and that it is a gift and a privilege, not a right. We must earn life once it has been awarded us. Life asks for rewards back because it has favored us with animation.

“So while our art cannot, as we wish it could, save us from wars, privation, envy, greed, old age, or death, it can revitalize us amidst it all.

“Second, writing is survival. Any art, any good work, of course, is that.

“Not to write, for many of us, is to die.

“We must take arms each and every day, perhaps knowing that the battle cannot be entirely won, but fight we must, if only a gentle bout. The smallest effort to win means, at the end of each day, a sort of victory. Remember that pianist who said that if he did not practice every day he would know, if he did not practice for two days, the critics would know, after three days, his audience would know.

“A variation of this is true for writers. Not that your style, whatever that is, would melt out of shape in those few days.

“But what would happen is that the world would catch up with and try to sicken you. If you did not write every day, the poisons would accumulate and you would begin to die, or act crazy, or both.”

And then he says the following:

Rest in peace, master.