Theodora Goss's Blog, page 27

June 10, 2013

The Graveyard

On my last day in London, I went to a lecture on graveyards and then walked around the Abney Park Cemetery in Stoke Newington. Here is me in the cemetery:

(Is there a difference between cemeteries and graveyards? I’m guessing it’s another one of those instances in which the English language has two ways of expressing the same concept: one from a Latin root, one from Anglo-Saxon.)

The lecture was by a journalist who had researched and written a book on graveyards. He made the point that most of the people in large, elaborate tombs were now forgotten. They had wanted to be remembered, perhaps expected to be remembered, but a generation later, no one knew who they were. Their graves were no longer visited.

And then he talked about the people who were remembered, whose graves were still visited. John Keats. Oscar Wilde, whose grave was once covered with lipstick stains from where people had kissed it. (It has since been cleaned and a glass barrier put up, but I think the kisses are now left on the glass?) Keats was so certain he would be forgotten that all he wanted on his tomb were the words Here lies One Whose Name was writ in Water. His friends added, This Grave contains all that was mortal, of a YOUNG ENGLISH POET, who on his Death Bed, in the Bitterness of his heart, at the Malicious Power of his enemies, desired these words to be Engraven on his Tomb Stone.

Last year, I visited the graves of Louisa May Alcott, Henry David Thoreau, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Ralph Waldo Emerson. (They are all in the same graveyard in Concord, Massachusetts). On each of them, admirers had left letters, flowers, small artifacts. When I visited the grave of J.R.R. Tolkien on this trip to England, I saw the same thing. Why do we remember certain people? Because they have given us something, and we care about them even in death. They live on for us through their words, their paintings. Their influence lives on, so for us they have never really died.

I loved walking around Abney Park Cemetery. As you can see, it’s almost a wild space in London: the vegetation has grown up so. I was with friends, and we rambled along the paths, looking at the gravestones. My favorite was a tomb with a lion on top: I’ve included a picture of me with the lion at the end of this post.

The lecture and walk really made me think about what I want to accomplish in my life, how I eventually want to be buried. Because, you see, I want to be one of the people who are remembered for having contributed something. I don’t care so much about a gravestone. It can be as plain as plain (although I’ve always liked the idea of an angel, because in a book I read as a child, two friends meet beneath a tomb with an angel on it). What I care about is the work, doing something meaningful.

We never know whether our work will be meaningful, of course. It could be forgotten. So much art, of heart and skill, is forgotten. What is remembered is the art that changes something, that touches us in a deep way, and who knows whether a particular piece of art will do that? All we can do is produce, keep producing, do our best.

Not everyone cares whether or not they will be remembered after their deaths — quite a few people have explicitly told me that they don’t. But I would like my work to have that sort of impact.

Which means that it’s time to get back to work. I’m in Budapest, I have two weeks before I need to be somewhere else. And I have a novel to write.

June 8, 2013

On Bluebeard

This blog post is really about how differently men and women can perceive certain things, but I didn’t think that would make a very good title. And Bluebeard does come into it, as you’ll see.

Some time ago, a friend of mine whom I will call Nathan, because his name is Nathan, and I were having a conversation. Nathan is a big, strong guy, about twice my size. He told me that when he had lived in New Orleans, he had loved walking around the city alone, late at night. I said to him, “Nathan, I’ve never walked around a city alone late at night.” There was a moment of silence, and then he said something like, “Oh, right. Sometimes I forget how different it must be for a woman.”

I’m writing this post in part because there have been conversations recently, in the media and on the internet, that have made clear how differently men and women can perceive certain words and actions. Some of those conversations have been about the literary world I live in, particularly the fantasy and science fiction corner of it. And the point I want to make, centrally in this blog post, is that something that may not seem threatening to a man may seem profoundly threatening to a woman. I’ll give you an example.

Scenario: A woman passes a man on the street. He says, “Hello, beautiful.”

How the man perceives this: “I paid her a compliment.”

How the woman perceives this: “Is he going to attack me?”

I don’t know if this is true for all women, in all circumstances, but if I’m the woman in that scenario, particularly if I’ve been walking down that street absorbed in my own thoughts, as soon as I’m spoken to I will immediately check my surroundings. What time of day is it? Is there anyone else on the street? How threatening does the man seem? (Although I have to add, if I am completely honest, that I never walk down a street lost in thought. I used to when I was younger. I’m smarter now.)

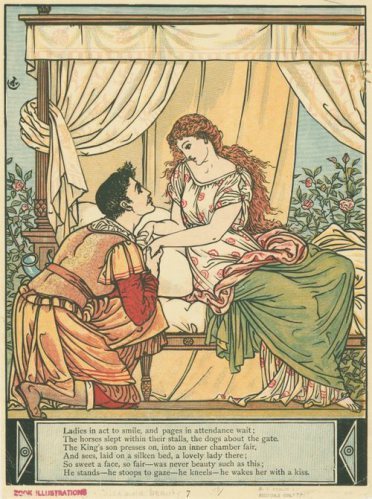

When I teach my class on fairy tales, I ask students about the moral of “Bluebeard.” Charles Perrault gives us a moral, clearly marked “moral,” at the end of the tale: “Curiosity, in spite of its appeal, often leads to deep regret. To the displeasure of many a maiden, its enjoyment is short lived. Once satisfied, it ceases to exist, and always costs dearly.” I ask my students, is that really what we learned from the story?

No, they tell me. That moral doesn’t make sense. If Bluebeard’s wife hadn’t been curious, she would never have known that he had killed his previous wives. And although he tells her that he’s going to kill her because of her curiosity, and we can infer that he killed most of his other wives for the same reason, what about the first wife? Why did he kill her? Clearly this is a man who simply likes killing his wives, and will eventually think of a reason to kill again. So, I ask them, what is the moral? And eventually we come up with something like this:

“Make sure you know whom you’re marrying, because your husband may be a serial killer.”

If you’re a woman, and you’ve lived for a while in the world, you’ve learned to be cautious. You’ve learned that you don’t know who people are, or what they’re capable of, until you’ve known them for a long time, and sometimes not even then. If a man is bothering a woman, it’s easy for another man to say “Ignore him. He’s just a creep.” Or “He lacks social skills.” But the woman in that situation has to approach it by thinking, what is the worst case scenario? What is the worst that could happen? And then she has to act based on that supposition. Often that means acting swiftly, decisively, with maximum effect. Because you have to establish, definitively, that you are not to be messed with.

She will be told, “You’re overreacting.” But she will also know that if something does happen, if there is a worst case scenario, she will be told, “You should have paid attention to the warning signs.” Either way, she faces the possibility of being blamed.

Let’s go back to that first scenario, with the woman walking down the street. If the man who thought he had paid her a compliment knew that she was assessing him as a potential attacker, he might blame her: he might say, why didn’t she realize that I was trying to be nice? What he wouldn’t know is how many times she had been approached on a street by a man who said, “Hello, beautiful,” and then continued with a sexual proposition. For an average woman, it would be a least once, but probably more than once. After a while, if you’ve been living while female, you get a sort of PTSD. Most women have been through assaults of various kinds. (I once looked up from reading a book in the public library to see a man masturbating on the seat across from me. I think I must have been about fourteen?) Most women have dealt with some sort of silencing or discrimination. (When I was at Harvard Law School, there were male students who argued that women who were going to take time off to have and care for children were taking up space that should go to qualified men.) This history conditions how they respond, whether to a compliment on a street or to male writers who talk about them with a lack of respect (see the latest SFWA scandal). (It’s also worth knowing that women talk to one another: we know when a male writer regularly hits on young female writers at conventions.)

“Bluebeard” has been interpreted in a variety of ways, but its simplest meaning is a cautionary one, to women. What it really says is, be curious, be bold, protect yourself. Considering the things women have to deal with, it’s scarcely surprising that they have learned this particular lesson.

I know I’ve put a lot into this blog post, and parts of it may not fit together with perfect logic. But it represents a series of things I’ve been thinking recently about differences in perception. If you’re a man and want to work or socialize with women, it’s probably worth considering how their perception may be different from yours, and what may lie behind that difference.

June 7, 2013

The Journey

I haven’t posted for a long time.

In the Preface to Lyrical Ballads, Wordsworth famously writes,

“I have said that poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility: the emotion is contemplated till, by a species of reaction, the tranquility gradually disappears, and an emotion, kindred to that which was before the subject of contemplation, is gradually produced, and does itself actually exist in the mind. In this mood successful composition generally begins, and in a mood similar to this it is carried on; but the emotion, of whatever kind, and in whatever degree, from various causes, is qualified by various pleasures, so that in describing any passions whatsoever, which are voluntarily described, the mind will, upon the whole, be in a state of enjoyment.”

I think that describes blog posts rather well, actually. When I write a blog post, it’s often because at some point in the past, usually the recent past, I felt something. And now I want to do something with that feeling: I remember it, and I write about it. It’s usually something I feel strongly about, or rather felt strongly about. If I’m still feeling it strongly, if the experience of it is too recent, I can’t write about it. I can’t turn it into coherent thought, cohesive narrative.

(The pictures I’m including in this blog post were taken by Terri Windling, on a day when she and her daughter Victoria and I walked along the hills behind her house, accompanied by her dog Tilly. As you can see, we met some Dartmoor ponies.)

The reason I haven’t been writing is that I’ve been living too much. There has been so much going on in my life, both internally and externally, that I haven’t wanted to sit down and write about it — I haven’t been able to achieve enough distance from it to turn it into a blog post, or a series of blog posts. So why am I writing tonight? Because I’m in London, all alone in a large Victorian house, late at night. I spent the entire day alone, the first time I’ve done so in I don’t know how long. And you know, it was heavenly. I’m enough of an introvert that I need regular breaks from people. Yesterday, I spent an entire train journey through the English countryside entirely silent, which was blissful. And today restored some of the tranquility I had lost on my travels.

What I wanted to write about tonight, just a bit, is the strange journey I’ve been on. I left Boston three weeks ago, flew directly to Budapest, and then three days later flew to London. I spent some time here, mostly with friends although I did walk around alone for a day and see Sir John Soane’s Museum. Then I visited Oxford and the surrounding area, spending some time in Kelmscott Manor. I headed down to Glastonbury, seeing famous sights along the way: the White Horse of Uffington, Avebury, and Stonehenge.

In Glastonbury, Liz Williams read tarot cards for me. The reading was all about transformation, about the strange liminal place I was in my life, my attempt to figure out what was to come. And it gave me a message: you have to let go of the old before you can accept the new. Then I went down to the village of Chagford, to visit Terri Windling. There, I had several conversations with some very wise women (including Terri, of course). And on my last day there, something strange happened: I met a spiritual teacher named Ocean WhiteHawk, who just happened to be staying in the same Bed and Breakfast. We ate breakfast together and started talking, and she offered to embed a sentence in my subconscious that would help me in the transition I’m going through. Which she did, just before I left. So the entire journey down to Chagford, my stay in that village, turned out to be a spiritual journey as well as a physical one. The whole thing, from start to finish, taught me.

Those are the best kind of journeys, I think. There’s no point to going somewhere if, when you get there, you’re just going to be you, there. You go on a physical journey to be transformed internally, spiritually. At least, I do. The great lessons of this journey, for me, were twofold: (1) trust the transformation, and (2) complete the old so that the new can begin properly. Those are the things I’m going to be working on. And I’ll try to post more: whether or not I do will depend on my tranquility, on whether I can find it again. I am, at least, going to try.

May 17, 2013

In Budapest

I’m sitting in the California Coffee Company near Kálvin tér, in Budapest. I come here to have my morning latte, and to use the free wifi. The latte here is very strong, the strongest I’ve ever had. A Starbucks latte is not in the same category.

I haven’t posted for a long time, partly because I’ve been so busy and partly because my life feels as though it’s in such turmoil right now. Have you ever had times in your life when you’ve felt as though you’re in transition? Well, that’s where I am right now, only I don’t know where I’m in transition to. I know where I’ve come from: finishing my PhD, moving into the city. Changing my life in a fundamental way. I remember what it felt like before that, while I was still finishing the PhD: the sense of stasis, as though I could not get out. The stillness, and the desperation that accompanied it. And now I’m in the storm, it’s not still anymore. Only, I don’t know where this particular craft is sailing. There’s new land somewhere, but I have no idea where it is or what it will look like.

These thoughts were prompted in part by looking in the mirror this morning. It was the hall mirror in my grandmother’s apartment, and it had been there since I was a child. Which means that when I was four years old, I looked in that mirror. Who could ever have imagined, then, that I would be back, at this age? Looking into that mirror again, so different and yet that little girl, all grown up. I could never have predicted my own life.

Which means that I probably can’t predict what’s going to happen either, even in the next year.

But right now I’m sitting here, having just drunk my latte and feeling a little shaky (it’s so strong, and I’ve been up since 4:00 a.m. Budapest time, because the birds at dawn are so loud). I thought I would post some pictures of the apartment. If you want to see more pictures of my trip, go look at my Facebook page. I’m posting a bunch of them there.

So first, let’s walk down the street. Do you see the coffee shop on the right? That’s where I am right now.

We enter the apartment building through this corridor, large enough to admit carriages (which may be what it did at one time). It leads to a central courtyard, but we’re going to go up the stairs.

They are stone stairs, and have looked exactly the same since I was a child. Getting my suitcase up them was probably the hardest part of my entire trip! (Of course, I was exhausted by then. I hadn’t slept all night.)

Let’s pause in the hall and take a picture of me in the mirror. Yes, this is the hall mirror that caused such introspection.

And here we are. The apartment is furnished exactly the way it was when my grandmother was living here. (She died several years ago.) Sometimes I think about how beautiful it could be, with those high ceilings. It’s not beautiful now, but it’s nice to be back here.

This morning, I called the shuttle company and reserved my shuttle to the airport tomorrow, when I’m heading to London. I will spend a week there, and then go to Oxford, then Glastonbury, then a small village called Chagford in Devon. Whenever I complain, and I certainly do complain, I remind myself how fortunate I am to have the life I do, to be able to do the things I do. There are things I want that I don’t currently have: safe harbor is one of them. But I think they’ll come? I just have to wait. And hope.

April 14, 2013

Adventurous Spirits

I read two quotations recently that struck me as interesting and worth thinking about. They also bothered me a little: that’s how I knew they were worth thinking about! Here is the first one:

“Make a radical change in your lifestyle and begin to boldly do things which you may previously never have thought of doing, or been too hesitant to attempt. So many people live within unhappy circumstances and yet will not take the initiative to change their situation because they are conditioned to a life of security, conformity, and conservation, all of which may appear to give one peace of mind, but in reality nothing is more damaging to the adventurous spirit within a man than a secure future. The very basic core of a man’s living spirit is his passion for adventure.

“The joy of life comes from our encounters with new experiences, and hence there is no greater joy than to have an endlessly changing horizon, for each day to have a new and different sun. If you want to get more out of life, you must lose your inclination for monotonous security and adopt a helter-skelter style of life that will at first appear to you to be crazy. But once you become accustomed to such a life you will see its full meaning and its incredible beauty.” –Jon Krakauer

Jon Krakaur is most famous for writing the book Into the Wild. He’s the sort of person who’s been up Mount Everest. The sort of person who climbs mountains for fun. What bothers me about the quotation is that I think he’s right. For me, anyway: I feel most alive when I’m not quite sure what the future will bring, but I’m fairly sure it will bring something. What seems to scare me most is the possibility of stasis. But I think the new experiences he describes can take many different forms: going back to school is a new experience, having a child is a new experience, starting a business is a new experience. Planting a garden can be one as well. Some experiences are quieter than others, but they can still be new and exciting. They can still be adventures. Also, I think if adventures are to be effective, if they are to be adventures at all, you need a certain level of planning. There is, after all, a difference between an adventure and a disaster: Krakauer’s ascent of Everest was a disaster, although it did furnish material for another book. The adventurous spirit needs to be accompanied by the spirit of practicality.

A side note here: I always get a bit angry when people tell me there is nothing I can’t do. I hear this a lot, actually . . . The reason it bothers me is that it’s so patently untrue. There are all sorts of things I can’t do, because I don’t have the time, or the money, or because I don’t want to make the compromises that doing them would entail. There is an odd notion out there that life has no limitations. But life has plenty. That’s partly why it’s life.

Here is the second quotation:

“When we are doing something because it is expected of us or to please somebody else or because we are afraid of somebody else, we become further alienated from a sense of living authentically.

“If we just keep living out a role we know well, the cost of that is to become increasingly cut off from that which is in the collective unconscious, that which not only nourishes us, but also provides the raw material that allows us to mess up.

“Very often in transition periods, that’s exactly what is called for, a change by going through chaos, of losing the way, of being lost in the forest for some time before we get through and find our path again.” –Jean Shinoda Bolen

At heart, both of these quotations are about the willingness to accept uncertainty: in the Bolen quotation, for a while, and in the Krakauer quotation, as a condition of life. Although the Bolen quotation talks specifically about being lost for a while, of accepting that period of being lost before finding the path. That quotation bothered me because it felt so true, and in a way uncomfortable: it was like one of those signs saying “You Are Here.” Because that’s exactly where I am, lost in the forest for a while, doing the work I’m sure I want and need to do, but not knowing where it will lead. Trying to figure out the next adventure.

I think what I will take from both of those quotations is, that’s all right. Life is a series of adventures, and those of us who have adventurous spirits will seek them out. But that means we may feel lost intermittently: we will always be losing and refinding our paths. I think that’s what adventures are all about.

I do have faith that the path is there, waiting. And that it will become clear, eventually.

April 9, 2013

Going for Real

I don’t play video games.

I have friends who do, and I hope they won’t be angry with me for what I’m about to write. It applies to me, and not necessarily to anyone else. But I don’t see the point of them. I don’t want to spend time going into a secondary reality if, when I return to this reality, I haven’t brought something back — some wisdom, some sense of beauty, something that has changed me and that I can use to change the primary world I live in.

As soon as I use the term “secondary reality” here, you know I’m referring to J.R.R. Tolkien’s essay “On Fairy Stories,” in which he says that when we tell stories, we are creating a secondary reality we can enter. He justifies fantasy by saying we are allowed to create things that don’t exist, that those things may indeed have a greater reality than things in our primary world. Pegasus may be more real, in a sense, than the Chrysler building. I’m not so sure about the Chrysler building, actually, because it’s developed its own mythology. But I’m pretty sure that Pegasus is more real than the stock market. Perhaps being real isn’t predicated on actually existing. Odysseus feels real to me, as does Little Red Riding Hood.

What I’m trying to get at, I guess, is that some things feel real and important, and some things don’t. Daffodils and fairy tales do. Video games don’t, and much of contemporary popular culture doesn’t either. I know this is terribly subjective.

Video games and myths are both part of the continuum of the fantastic, and indeed video games can be based on myth. Could it be, then, that what I’m talking about has to do with the difference between Carl Jung’s idea of the collective consciousness and the collective unconscious? That video games are part of the collective consciousness, while the old myths reach much, much deeper than that? I’m trying to explain this intellectually, but really what I’m trying to explain is an instinct — a sense for the relatively realness of things. I always feel a little sick when I’m in a place that feels completely unreal to me. Being a corporate lawyer was like that. My work was consequential, certainly. But it felt unreal.

My goal in life is to live as real a life as possible, which includes those things that are fantastical but feel real to me. So I want a garden with daffodils in it, the old-fashioned kind that have such a sweet scent. And I want to read fairy tales, and write them. I want to wear clothes, not costumes, but I want them to be both modern and beautiful, which really means timeless. I want to eat fruit and vegetables from my garden. I want to hear birds, and streams, and the wind in the treetops.

I live in a large city, so I can’t have everything I want right now. But I’m trying to make life as real as I can. Until I can live here:

That, in case you haven’t guessed, is my witch’s cottage. Someday, I will live in a cottage like that, and write my books, and make magic . . .

April 8, 2013

Red Riding Hood

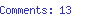

I’ve been teaching Jane Yolen’s novel Briar Rose to my students. It’s about a young woman named Rebecca whose grandmother, called Gemma, has always told her own distinctive version of the “Sleeping Beauty” story. Before she dies, she tells Rebecca that she was the princess in the fairy tale, and asks her to find the castle. She also leaves Rebecca a box of photographs, newspaper clippings, and official documents. Rebecca goes on a quest to figure out her grandmother’s past, and ends up traveling to Poland. The story goes all the way back to World War II and the Holocaust.

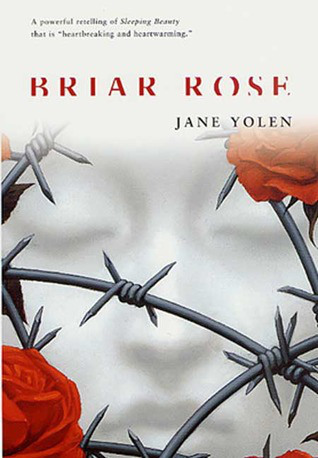

There’s a specific line in the novel that we discussed today: in Poland, Rebecca meets a gay man named Josef Potocki who tells her about what it was like in the days before the war, when Jews were already being singled out and forbidden certain activities. But he and his Jewish lover ignored all that, for a while. Josef says that they were “living in the belly of the wolf” without realizing it. Of course that’s a reference to another fairy tale, “Little Red Riding Hood.” The wolf is a metaphor: for the Nazi regime, for the coming war itself.

In class, we talked about why certain stories, fairy tales in particular, have lasted as long as they have. Why do we keep retelling them, over and over? I think the answer is fairly simple: because they’re metaphors. In The Uses of Enchantment, Bruno Bettelheim treated them as metaphors for internal psychological processes, but I think they can mean more than that. They can certainly function as metaphors for historical situations, like World War II. In Briar Rose, for example, Sleeping Beauty’s sleep represents our own tendency to sleep, to be unaware of what is happening around us. The book itself is an awakening, to what happened in the Holocaust. To the horrors we can perpetrate, the unpredictability of human life — but also to its sweetness. The book is a Prince’s kiss.

That wolf is important to me, and it’s what I want to write about tonight. It’s a metaphor, of course, and it can mean so many things. The wolf can mean cruelty, poverty, injustice. All of those negative things. But it can also mean our own wildness, which is necessary for our survival, because we can’t be all good, obedient Little Reds listening to our mothers. We need to wander off into the woods sometimes. The power of a metaphor is not only that it can mean different things, but that it can mean opposite things at the same time. The wolf is both something to flee from and something to embrace.

In my own life, there are wolves I need to avoid. And by avoid, I mean that when I meet them in the woods, I need to not listen, to not let them get me off track. They are the wolves of fear, of depression, of loneliness. All the wolves that stop you from going where you need to go. And there are the wolves I need to listen to: my anger, my ambition, my passion. All those things are wild, and sometimes not entirely under my control. But I need to hear what they have to say.

We are all Little Red Riding Hood. We are all walking through the forest, with rules and duties to guide us. Sometimes we need to keep to the path, sometimes we need to go off it. Sometimes we are devoured, and we need a Huntsman to save us. Sometimes, as in older versions of the fairy tale, we learn to escape from the wolf ourselves. And sometimes, as in Angela Carter’s “The Company of Wolves,” we learn to accept the wolf, to sleep between its paws.

April 5, 2013

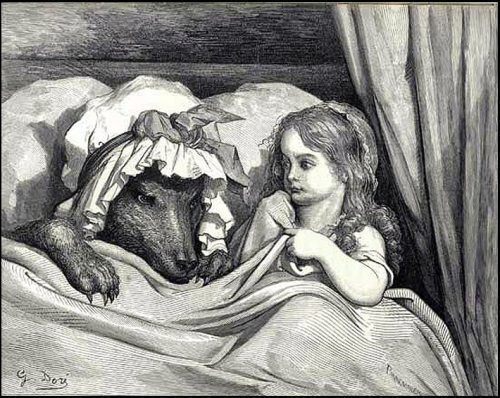

Magical Men

I wrote a blog post on magical women, so I thought I should write one on magical men as well. But the strange thing is that I know fewer magical men than I know magical women. I’m not sure why? I can tell you what magical men are like. Just like magical women, they are writers and artists who show you mystical, fantastical aspects of the world: artists like Brian Froude, Charles Vess, and David Shane Odom, for example. Or writers like Charles de Lint and Cliff Serutine. They show you different ways of thinking and being. I could certainly name others, so I’m not sure why it seems as though there are fewer of them than there are of the magical women I know. Perhaps I just know fewer personally, which means it’s my fault? Or perhaps our culture allows women to connect with the world in a magical way more readily. Perhaps they are not mocked for it, or told there is no profit in it. Perhaps there is something in nature, in the understanding and celebration of the natural world, that we still consider feminine? Even though it is men who have traditionally been though of as woodsmen, hunters. I don’t know.

What I do know is that I want there to be more magical men. We need them. (Of course, I think we need more magical women too. We need more magic generally.) We need men who are trying, not to climb the corporate ladder, but to save the world. (In whatever way presents itself. Because you know, there are a lot of ways to save the world. Some days, it may involve writing a poem, or planting a garden.) I suppose what this blog post expresses, really, is a kind of longing. Let there be men strong enough to march to the beat of their own drummers, as Thoreau said. I know, I know, they’re out there. I just wish there were more of them, and that the men I know (and I am lucky to have wonderful male friends) felt more free.

There is something about relative powerlessness that can, ironically, give you more freedom. Men are expected to be serious, motivated, ambitious. Women are allowed to create an Etsy store to sell their art or crafts. It’s a shame, really. So yes, I suppose I wish men strength, freedom, courage — to be magical.

I’m going to end with a poem I wrote some time ago called “Green Man” that is a love poem. I’m not sure if it’s the appropriate way to end this post, but somehow it feels right.

Green Man

Come to me out of the forest, man of leaves,

whose arms are branches, whose legs are two trunks,

rough bark covered with lichen. Come and take

my hands in yours, and lead me in this dance:

In spring, green buds will sprout upon your head;

in summer they will lengthen into leaves.

Oak man, willow man, linden man, which are you?

In autumn, they will fall, and through the winter

you will be bare, with only clumps of snow

or birds upon your branches.

Come and love me,

my man of leaves, my forest man. For you,

I’ll be an alder woman, birch woman.

In spring I’ll wear pink blossoms like the cherry;

in summer ripening fruit will bend my boughs;

in autumn I will bear, distributing

a hundred seeds, our children. And the birds

will sing my praises. Let us learn to love

the sun and wind together; let us twine

our bodies, filled with sap, until we make

a single tree on which two different kinds

of leaves are growing, where birds build their nests,

among whose roots the squirrels hide their nuts,

storing them for winter.

A hundred years from now, we will still stand,

crooked perhaps, the sap running more slowly,

our two hearts beating, separately and together,

under the summer skies, in autumn rains.

April 4, 2013

Sleeping Beauty

Since I’ve been teaching a class on fairy tales, I’ve been asked, by students and by people who are simply interested in the subject, what fairy tales “mean.” And I have to say that in my personal opinion, they don’t “mean” anything. Bruno Bettelheim thought they did: he thought he could use Freudian analysis to explain their psychological significance, which would be timeless and universal, since human beings were always the same everywhere. Except they’re not. They differ because of the times or cultures in which they live, because of race or gender or age. They differ even as individuals. Fairy tales have lasted so long precisely because different versions have meant different things to different people at different times.

So I think it makes as much sense for me to talk about what a fairy tale means to me personally as to try to find some sort of universal meaning. To me, fairy tales are about the journey of the soul, and the one I’ve been thinking about lately, because I’ve been teaching it, is “Sleeping Beauty.” So what does “Sleeping Beauty” mean to me?

The fairy tale falls into three parts: the gifts of the fairies, the hundred-year sleep, the awakening.

I. The Gifts of the Fairies

We are all given gifts by the fairies, and I think it’s useful to be honest about what they are. After all, they are gifts — we did nothing to deserve them, we can only be grateful for them. Seven good fairies came to my christening. (But be careful: it’s difficult to tell a good fairy from a bad fairy. Gifts come with a price, and what may seem like a curse can turn out to be a gift in disguise.)

The first fairy said, “I give her intelligence. She will always do well on standardized tests, and so she will be able to get into some of the best schools in the country. However, she will also be smart enough to see that the value systems she is is expected to live by are meaningless. This will make her try to live a different kind of life, which will cause her difficulty and heartache.” I told you, didn’t I? Gifts come with a price. Nevertheless, they are gifts, and we have to be grateful for them.

The second fairy said, “I give her strength. She will not always feel strong, but she will always be able to do what she needs to. She will always get through.” I’m grateful to that fairy.

The third fairy said, “I give her grace. She will be physically graceful, and will love to dance. But more than that, she will be able to accept defeat, and when it comes, she will be able to say, oh well, what next? She will have to do this more often than she would like.”

The fourth fairy said, “I give her empathy. She will feel what others are feeling, without wishing or trying to. She will not be able to stop doing so, and sometimes she will have to hide in a small room, or in a corner of her mind, simply to get away from other people.”

The fifth fairy said, “I give her beauty. However, she will never be able to see it herself, or believe in it, not when she looks into the mirror. She will, on the other hand, be able to see the beauty in the world, and in others.”

The sixth fairy said, “I give her poetry: the ability to hear the rhythms of language, and to write in language as though words were her natural element. This will be the most important gift she receives, and what will save her.”

That was, of course, when the bad fairy stepped in and said, “I curse the child. While she is still a child, she will lose her home: her country, her family. And she will never again find a place where she belongs.”

Of course, the seventh good fairy was hiding out (I think they’d been through this routine before). She stepped forward and said, “I can’t change the curse, but I can give her a gift that will help her bear it. She will always be a good traveler, able to pack efficiently and create temporary homes for herself wherever she goes.” I think that fairy was supposed to give me either humility or self-confidence, either of which would have been useful gifts. But she had to mitigate the bad fairy’s curse, you see.

We are all given gifts, we are all cursed in our own ways. That is the first way in which we are like the Sleeping Beauty.

II. The Hundred-Year Sleep

The sleep doesn’t always last for a hundred years, and it doesn’t necessarily happen once. It’s the state in which we fall asleep metaphorically, in which we forget who we are. I think I fell asleep for a while in my own life, during the years I was trying to finish the PhD. There’s one thing I can tell you about that experience. Awakening? Is so. Incredibly. Painful.

III. The Awakening

In different versions of “Sleeping Beauty,” the princess awakens in a variety of ways. Awakening to the prince’s kiss is actually a fairly modern development. In some of the earliest versions, the princess sleeps right through two pregnancies.

The thing about fairy tales is, we can always rewrite them. There are always new versions to be written. In my version, at some point the princess realizes she’s asleep, and she tries to wake up. She tries several times, each time thinking she is awake, but eventually she succeeds. She sits up in bed, and instead of a prince, sees a sign on the wall. I’m pretty sure it was left by the bad fairy. (I mentioned, didn’t I, that you can’t actually tell whether fairies are good or bad? They are both, and neither, and either at different times.) The sign says,

YOU MUST SAVE YOURSELF

Which, I’m pretty sure, is the beginning of a new fairy tale.

April 3, 2013

Magical Women

I realized, this morning, that there are certain people whose Facebook posts I always look forward to reading. Most, although not all, of them are women. I look forward to reading them because even their Facebook posts reflect a quality they have, an inner brightness. They are bright spirits, which doesn’t mean that they are always cheerful or optimistic. No, it means that they are always honest, direct, clear. There is something fundamentally true about them. They shine brightly, like lights that illuminate parts of the world. They show you things.

The ones I am thinking of as I write this are Jane Yolen and Terri Windling, and if you don’t read their writing, you should. And then there is a group of artists, like Iris Compiet and Jackie Morris, Ali English and Bryony Whistlecraft. (Terri is also an artist, of course.) And there are bloggers like Grace Nuth. I love the images they post, the parts of their lives they share with the world.

I think of them as magical women. They make the world more magical, show me the parts of it that are magical, in case I’ve forgotten. But they also write about work. They are all doing wonderful, important work: this week, I’m teaching Jane Yolen’s young adult novel Briar Rose, which was edited by Terri Windling, in my fairy tale class. I think that’s partly where they get their magic and power, that dedication to the work that is truly worthwhile. To the arts in some form, specifically to the mythic in arts, and to arts that change the world. I think it takes a great deal of courage to be one of the people who tries to change the world in some way — I’ve heard too many people say that they’re not trying to change the world, that they’re just trying to entertain (particularly in their writing). But that’s the point of that? If you’re not trying to change the world, what are you doing, and why? I mean, doesn’t the world need changing?

I still remember when I was a corporate lawyer, doing work that other people thought was important. In Manhattan, working with major corporations, flying around the country. I certainly looked and sounded important, and yet I knew the work I was doing was not, ultimately, worthwhile. That it changed nothing, except by making corporations, and their wealthy shareholders, richer. I could feel the hollowness of it. That was why I left.

The life I have now can be exhausting — it’s been particularly exhausting this year. But I know the work I do, whether it’s teaching or mentoring or writing, is all worthwhile. It’s all work that changes the world, even if only in the most minor ways, by changing one person’s perception. I wonder if that is, after all, the definition of magic?

There are all sorts of things I wish for right now in my life, but one consistent wish is to become one of those bright spirits, who speak honestly, directly, clearly. And with courage.

While I was thinking about this blog post, I ran across two videos that I want to include here. The first is an interview with the artist Evelyn Williams, who died late last year. Her art has such intensity. It is sometimes almost too much to take, but how interesting it is — as she was.

The other is a song from Noe Venable called “Sparrow I Will Fly,” which somehow seemed appropriate just now. The song goes, in part,

I’m still waiting

in the cyclone’s eye

for the day when like

the sparrow I will fly

Two videos by two magical women . . .