Theodora Goss's Blog, page 28

April 2, 2013

Being Seen

I read a poem this morning, the first of the poems that will be published on Tor.com as part of Poetry Month. It’s by Neil Gaiman, and it’s called “House.” It starts like this:

“Sometimes I think it’s like I live in a big giant head on a hilltop

made of papier mache, a big giant head of my own head.”

The poem describes how the man lives in a house shaped like his own giant head, cleaning the windows (which are the eyes), mowing the grass around it. And people drive past, waving not to him, but to the giant head, because “they think the house is me.” It isn’t, of course.

What it is, is a metaphor. I suppose a giant house shaped like a head would have to be!

The most important lines of the poem, to me anyway, are these:

“I’ll be sleeping there, or polishing the eyes, or weeding the lawn,

but no-one will see me, no-one would look.”

There’s a sense in which this is a poem about being someone like Neil Gaiman, someone so famous that he is no longer seen as a person. People no longer see him. They see the giant Neil Gaiman head. But it’s also a metaphor for how we experience other people in general: we so often don’t see them, and they so often don’t feel seen. Instead, we see who we think they are, the giant heads of themselves. The houses they inhabit, not the selves that are the inhabitants.

Strangely enough, some of the most authentic people I’ve met have been people who are famous. It’s as though they insist on authenticity — they insist on being themselves, specifically because they feel as though they are being made artificial. They know that people don’t see them, and so whenever they can, they insist on being seen as they are, even if that image is not particularly flattering. They take actions or express opinions that may be controversial, that may cause debate, but reflect what they think and feel. They want, so much, to be seen not as constructs, but as people.

It’s uncomfortable, not being seen as a person.

But we all get that to a certain extent: the giant heads we live in are constructed partially by us, but also partially by others, by who they think we are. And if we are writers or artists, there’s an assumption that we are our writing, our art.

There’s something I’ve learned about writing these posts, which is that when they become hard to write, when the sentences feel like snakes twisting around in my hands, it’s because the subject it too personal. It hits too close to the giant head that is my home. And this subject is personal, I think. Because we all get this, and I get it too: the sense of living in an artificial construct that is perceived as my self, that is addressed instead of me. The value of friends is that they see you, the real you: they automatically look through the windows and know you’re in there. One of the saddest thing, I think, is meeting someone you would like to be a friend who doesn’t do that, who can’t seem to see the person in the construct.

There is a particular pain in not being seen. In not being perceived as a person.

A friend of mine and I were talking about this last summer, sitting in my grandmother’s apartment in Budapest: two women who write fantasy, discussing how easy it seems for people to confuse the writer with the work, or even simply with an image online.

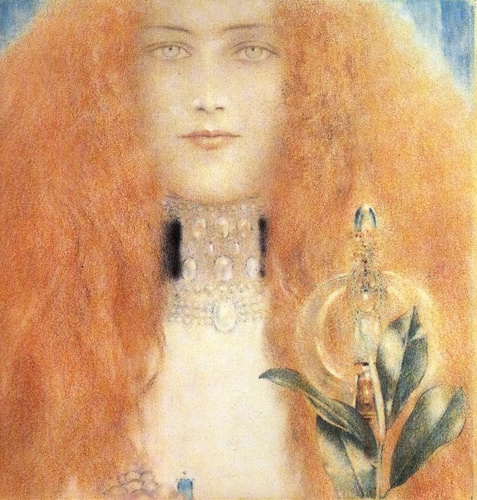

As my illustration for this post, I’ve chosen A Woman’s Head by Fernand Khnopff. She’s beautiful, isn’t she? Iconic, almost. But she must have been a real woman who modeled for the artist. I wonder who she was, and what she was like as a person . . .

April 1, 2013

On Loneliness

I’ve been thinking about loneliness lately, because friends of mine have been feeling it to various degrees, and of course I’ve felt it at various times in my life. It seems an important topic to address, and one we don’t address very often. It’s one we don’t want to address, I think because it’s an emotion we’re ashamed of feeling, as though we should somehow be sufficient onto ourselves. As though if we were stronger, strong enough, we would not feel it.

And yet we’re human beings, made to connect with one another. We evolved as social animals, and without that connection, we feel a little lost, a little aimless. We don’t quite know what to do. It’s as though we are all, after all, incomplete, and are completed only by each other. Not one of us is sufficient onto ourselves.

And so I thought, what is it, exactly? What is loneliness?

There was a quotation I put on my tumblr a while back: “Loneliness does not come from having no people around you, but from being unable to communicate the things that seem important to you.” –Carl Jung

I think that starts to get at what loneliness is. It’s not being alone, and people often say they can be lonelier in a crowd than by themselves. That’s because in a crowd, the lack of connection becomes more obvious to them — they feel it more. I think Jung is right to stress that loneliness comes from a lack of communication, of genuine interaction. But I want to offer a different definition:

Loneliness comes from being treated as a means rather than an end.

We all want to be seen, and to mean, as ends: as the people we are, as complete wholes. And yet so often we exist for other people as means, as the parent who will raise them, the spouse who will support them, the teacher who will help them. That’s unavoidable: we will always to a certain extent be seen as means. But we also need to be seen as ends, and when we’re not — that’s when we get lonely. When we are in a crowd and feel as though we’re not seen. I suppose that’s why fame also creates a kind of loneliness — you become a means for other people, who read you or watch you. You become a part of their internal landscape, but it is not after all you. It it whoever they imagine you are.

We all need at least one person in the world to see us as we are, and to accept that. To love that, because the opposite of loneliness is being loved, and loving is seeing and accepting.

And you know what? It is very difficult to find. I’m not sure why. Perhaps because at heart, we are all impatient and afraid, and truly knowing and valuing another person takes time and vulnerability. We all want to be loved, without necessarily doing the work of loving. But it doesn’t really work that way, does it? You have to do both. One way out of loneliness is loving, but you need it back, eventually. It can’t simply go one way, which is why taking care of a child can be a lonely endeavor — a child, no matter how affectionate, can’t yet see you as you are, and won’t for years.

I feel as though I should have some sort of grand pronouncement here at the end, but all I have is this: try to find people who love you, and love them back. I think it’s as simple and as difficult as that.

This image is Dreams II by Heinrich Vogeler.

March 31, 2013

Being Strong

I had a strange realization, recently.

It was after meeting a friend for chocolate. There is a famous chocolate shop in Boston called Burdick’s. That’s where we met, and when I say for chocolate, I mean to drink chocolate, or eat any one of the chocolate items that Burdick’s carries. In my case, it’s a chocolate orange hazelnut cake that is one of my favorite foods in the world. My friend is one of those delicate, graceful women who look as though they wandered out of a fairy tale. She told me about the things that had happened recently in her life, which included death threats because of some things she had written. She had handled them as she seems to handle everything: gracefully, with strength and resilience. And I thought, wait, there’s a pattern here.

The strongest people I know are delicate, graceful women who look as though they wandered out of a fairy tale. (Yes, I know a number of these. I suppose it’s being a fantasy writer, because they are all writers and artists of the fantastic.) They post about finding pink taffeta dresses in second-hand clothing stores, and have overcome incredibly difficult childhoods. They have become famous writers, scholars with international reputations. They have created magnificent lives for themselves, despite opposition, sometimes illness.

They remind me of ballerinas, who look so delicate and graceful. And yet, when you get close to them, you realize they are all muscle. They are a combination of will and art. So the pictures I’ve chosen for today are Degas ballerinas.

We live in a world where physical strength is and will always be useful. Yet it seems to me that these women are stronger, in their own way, than the six-foot tall, two-hundred-pound men I know, and I know a few of those, too. (Sorry, guys.) Their strength is in not knowing when to give up. Giving up never seems to occur to them. Setbacks and adversity are seen as a part of life, a matter of course. Things to learn from, to grow from. And when these women get down and discouraged, as we all so, they talk to their friends. (It’s important to have friends.)

They support each other.

I’m not sure why this struck me so hard, recently. But it was a good realization to have: that strength means going on, doing the things you want and need to do. It means resilience. It even means stubbornness, as in not knowing when to give up, to take no for an answer. Doing what everyone tells you can’t be done, not because you believe in yourself, but because you may as well try as not. Thinking, “I’m not sure I can do this” every step of the way, but doing it. It means flexibility: thinking all right, that didn’t work, what other way can I try to do it? The women I’m thinking of aren’t tough: they get hurt, they cry. They don’t try to be tough. They remain open to the world, to the wonder and the pain of life. They remain vulnerable. They fail and fall, then they pick themselves back up, try to understand what went wrong, what they can change in themselves that will produce a different outcome the next time. And, like beautiful, unstoppable forces, they just keep on going . . .

March 30, 2013

Being at ICFA

I’ve been terrible about updating this blog, haven’t I? I’ve just been so unbelievably busy, last month and this month. But I have to post something. I feel as though I can’t let a month go by with no posts at all.

I was able to step out of the busyess for at least a little while last weekend, at ICFA (the International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts). It’s my favorite of all the conferences, either academic or industry. I like it so much because it’s small, and I know all the writers and many of the scholars there, and so it’s like meeting a group of your best friends again, many of whom you haven’t seen for an entire year. There are things to do: I gave two readings, one of “England under the White Witch” and one of my story “Estella Saves the Village,” which is in Queen Victoria’s Book of Spells. But most of my time was spent catching up with people, hearing what they had been up to, what they were planning on doing. And such people! The very best writers in the business. Writers like Kij Johnson and Andy Duncan and Jeffery Ford. And I got to meet Neil Gaiman, which was of course a pleasure.

I’m going to include two photographs here. The first one was taken at the banquet, which occurs on the last night, by Ellen Datlow.

I’m rather proud of this dress because I found it at Goodwill for $10. I bought it specifically for the banquet, but by the time ICFA came around, I had lost some weight and it no longer fit as well. Which isn’t usually a problem, but this was a strapless dress. There were loops for straps, so it had once come with them, but no straps with the dress. So I hunted all around town until I found some ribbon of the right color and matching thread (at two different stores). And I made straps!

The second photograph was taken by Jim Kelly, and it’s of me with fabulous writer friends Maria Dahvana Headley and Kat Howard. I thought we looked pretty smashing!

What I value most about ICFA is the sense of camaraderie, that we’re all in this together. That those of us writing and studying the fantastic are part of a community — we care about and take care of each other. Now that I’m back in Boston, I miss my community, but I know that I’ll see them all again, while I’m in Europe this summer, when I teach at Alpha and Stonecoast, and of course at Readercon, where one of the guests of honor will be Patricia McKillip, who influenced me so much when I was a teenager. And of course I’m in constant contact with them, and with the larger community all over the world, online.

Writing is such a solitary activity! I think it’s important that we come together, we writers. We need to hear what others are doing, tell them what we are doing — check in with each other and with other parts of the industry. Which I suppose is why we have this yearly round of conferences and conventions. It’s expensive, and there are many conventions I wish I could go to but can’t afford. Still, whenever I do manage to go, it’s so worth it.

Also, it gives my evening dresses something to do . . .

February 9, 2013

In Transition

Today was a Very Snowy Day.

Yesterday, the snow came down all day, and today my street looked like this:

I live on a street with both apartment houses and university buildings, and you can see the mix in this picture. The snow was at least two feet deep everywhere I walked, except of course where the streets and sidewalks had been plowed. (That’s one nice thing about living in the city: all the plowing is done for you.) As I walked around the neighborhood, I stopped to take a picture of myself reflected in the post office window:

That’s me dressed for winter in a Land’s End jacket and Timberland boots. When you live in Boston, you have to be ready for winter weather. I walked around a bit, watching the students enjoying the snow. We have so many students here from other parts of the country, and from all over the world; some of them have never seen snow until they arrive in Boston. Today, I saw students building forts, having snowball fights, and taking pictures of themselves having the New England university experience. By Monday, the city will be moving again, and they will all be in classes.

I walked back to my building, which looked very much as it probably had on a winter day a hundred years ago:

It was nice to have a quiet weekend, because usually I’m so busy. This is a transitional period for me: I’m still doing all the things I was doing, and I’ve started doing all the things I’m going to be doing, and those are going on at the same time, which is exhausting. That will be my life for the next few weeks, although after that it will get easier. Transitional times are hard . . . But they’re necessary, because otherwise you can’t actually get anywhere. You have to go through the transitions.

There’s something I do to help me through them, a sort of mental game I play. I pretend to be the person who has already gone through the transition. I’ll give you an example. In the next month or so, I need to lose five pounds. (Don’t even start: I know that I’m perfectly healthy at my current weight. But I dance, and when I go to events I get photographed, and I know the weight I prefer to be, which is five pounds less than my current weight. Any less than that, and I start to look underweight.) So I think, what sort of person would weight five pounds less than I do now? Let’s call her Theo. Well, Theo would not be in the bad habit of staying up late at night, which would leave her tired and hungry and in need of a midnight snack. She would take care of her health, which means getting enough sleep and exercise. So the mental game is pretending to be Theo. I think, what would Theo do? And even more importantly, how would Theo think? And then I try to do and think that.

It just occurred to me, as I was writing this, that I actually have a picture of Theo. Here she is, just after her ballet class:

Doesn’t she look responsible, as though she’s sleeping and eating right? I wish I could be her all the time . . . But for now at least I can pretend, and that actually helps me through the transition, whether it’s a transition to being healthier, or having the career and life I want. Transitions are hard, and in some sense we’re in transition all the time, because life never stays still. But the major transitions, those times in our lives when we’re changing rapidly, and it feels as though the earth is shifting beneath our feet — those are when it can help to visualize who you will be after the transition is over, and pretend to already be her.

February 1, 2013

Being Exhausted

I did such a stupid thing tonight! I put something on the stove, and promptly forgot about it. Of course it started to smoke, which set off the fire alarm. Since I live in faculty housing at the university, my apartment is alarmed in the same way as a university dorm. Do you remember the nights when the dorm fire alarms went off, and we all had to file outside in our pajamas? I’m sure every university student has to go through that at least once. It’s a rite of passage.

The problem was, I couldn’t get the alarm to turn off again. It just kept beeping, in that incredibly loud, industrial, university fire alarm way. There’s a button you can push to turn the alarm off, but it wasn’t working. So I had to call building maintenance. The maintenance man came in about half an hour, but in the meantime, I put Persephone the Cat in the bathroom, which was the quietest part of the apartment, since I didn’t want the alarm to hurt her sensitive ears. And I went out into the hall, to escape from it myself.

That did give me an opportunity to meet my upstairs neighbor, a lovely woman who lives in the beautiful nineteenth-century apartment above me. She’s a Trustee of the university, and a friend of Elie Wiesel, and when she mentioned that she had met Katie Couric at a graduation event, I mentioned that I had met her too, at a cocktail party, since I had worked for the same firm as her husband. (She is much smaller than you would think, but just as perky.) So there was a silver lining to that particular cloud (of smoke).

This experience has led me to formulate a principle for myself: When you’re tired, don’t cook. Make yourself a cheese sandwich, eat a cereal bar, cut up an apple . . . But don’t turn the stove on!

The central problem is that I’m exhausted. There’s just so much work to get done, and it’s going to be like this for the next six weeks or so. After that, I will only be teaching three classes, rather than the current four, and my schedule will get easier. And then the summer will come, and I will be traveling around Europe in my usual way, going wherever I wish, seeing whatever I wish to see, meeting people. That will be lovely . . .

This is all worthwhile, all worth the exhaustion, because I’m in the process of changing my life into the one I want to live. I just have to remember, in the meantime, to take care of myself as much as I can. Which leads me to another principle for myself:

While creating the life you want to live, try not to kill yourself.

I’m tempted to post two pictures that I posted earlier on Facebook. Should I? Yes, I think I will. The first picture is one I took of myself last week. It’s of me completely exhausted, taken in the bathroom mirror.

The second one is of my street in Budapest. Yes, that’s Múzeum Utca, with the park around the Nemzeti Múzeum to the left, and the California Coffee Company on the corner. That’s where I go for my latte and free wifi in the mornings, and for a sour cherry brownie when I’m craving one . . .

I’m in the process of rearranging my schedule and my life, and this is the hard part. But eventually, it will all have been so very worthwhile . . . (I just have to not kill myself in the process.)

January 29, 2013

Being Loved

I think we all fundamentally want the same thing, which is to be loved.

This seems like such an obvious thing to say, and yet I think it’s not obvious at all, partly because we have such a vague sense of what love actually is. We use the word for so many things! I love roses, for example. I love them because they’re beautiful, and because of their scent, and even because they can be so difficult. And I do not love the hybrid teas that to me are not really roses. (You know, the roses that you get on Valentine’s Day, which have long stems and tight buds and are impossible to grow. For me, real roses are the old Gallicas and Albas and Damasks.) If only we loved people the way we love roses, or books, or houses! Books and houses we also love because they are beautiful and difficult. And yet, when we love people, we get frustrated by the difficulty . . .

I think that when we say we want to be loved, what we really mean is that we want to be understood, and accepted, and valued. Understood for who we are, and accepted and valued for that . . . And that’s where the difficulty lies, doesn’t it? Because so often when we love people, we want them to be different. We love them despite, rather than because. And yet, who among us wants to be loved despite? We want to be loved with our thorns, and even because of our thorns.

One of the reasons I’ve only been thinking about this recently is that in my family, we never talked about love. We were supposed to behave in a certain way: to become educated and cultured, to dress properly and act appropriately. The emphasis was always on our accomplishments rather than our relationships. But loving well is a sort of skill, really. Truly understanding, accepting, and valuing another human being is not an easy thing to do. Often love has something else mixed into it, a bit of dislike, a bit of disdain. That small thing will kill it, eventually. Because we can tell when someone does not truly love us, when that love is mixed with something else. We always know, even when we try to hide it from ourselves . . . Loving is something that takes honesty and courage.

It would be easy to love a rose without thorns, a book with no complicated passages, a house in which the windows did not stick in summer. A human being without old hurts or habits that displeased us. But perhaps that would not be love, just a sort of easy pleasure. Perhaps love is in the accepting, in the valuing.

Some time ago, I found a quotation from Jeannette Winterson that struck me. Here it is:

“There are many forms of love and affection, some people can spend their whole lives together without knowing each other’s names. Naming is a difficult and time-consuming process; it concerns essences, and it means power. But on the wild nights who can call you home? Only the one who knows your name.”

She’s talking about understanding: the first step in being loved is to be truly seen, and understood. You can spend your whole life in a relationship and realize that you’ve never really been understood, that the person you’ve been with has never known your name. That’s a horrible realization to have . . .

But if you can find a person who does . . . Well then, it’s as though you are no longer on a planet spinning through space. It’s as though you’ve found, in this universe that is ceaselessly in motion, a place on which to stand. Solid ground . . .

January 27, 2013

Shadowlands

Recently, I’ve had three friends announce publicly that they’re going through depression. They are all women, all beautiful, all incredibly accomplished. The sorts of women that other people want to be, and want to be around.

When I was going through depression, I was public about it too. I’m not sure there’s any other way you can be, particularly when you have a public presence, as they all do. People begin to wonder what’s wrong with you, why you’re not tweeting, blogging, writing. Still, there’s such shame associated with it, with admitting that you are less than all right. That you can’t, in fact, deal. And people can make it worse in a variety of ways, by saying it will pass, you will be all right. That you should cheer up, shouldn’t be so sad. The worst is when they remind you of how lucky you are to have what you do have, when they tell you that you are so much better off than many other people. The implication is that if you have a best-selling book, or a major award, or significant publications, you really shouldn’t feel depressed. That your depression is a sort of ingratitude.

Which ends up making you feel depressed, ashamed, and ungrateful.

When you’re depressed, it’s impossible to ignore the criticism, because it’s an external form of your own internal dialog. When you’re depressed, nothing rolls off your back.

(Funnily enough, a blog post I wrote recently received a similar critical comment from a nameless reader — that I was unaware of my own privilege, and ungrateful for it. I left the comment up because it demonstrated, better than anything I could have written, my point that if you have a public presence of any sort, you will be criticized by people who don’t know you or where you’ve come from. But that criticism is much harder to take, almost impossible to take, when you’re depressed.)

My depression was connected to a specifically difficult time in my life, the two years in which I completed my doctoral dissertation. It took a while to go away, even after I graduated. And it changed me permanently. I’m stronger than I was before in some ways, but more fragile in others. I will never again have the easy toughness I once had. I miss it, sometimes. Nowadays, my sense of joy is more delicate. I am more aware that beneath the sunlit earth, there are Shadowlands. (I used to call depression “going to the Shadowlands.” Depression isn’t sadness. It’s blankness. It’s when reality loses one of its dimensions and becomes flat, monochromatic.) I can feel them there, and I can tell when stress or loneliness or tiredness, those things we all experience, brings me closer to them.

I’m not writing this blog post to say anything in particular, except that it makes me sad (not depressed, but sad) to see such wonderful friends, such creative, artistic spirits, going through that. When I heard them speak out about it, I thought, what is the appropriate response when someone tells you they are dealing with depression? Back when I talked about my own depression, there were a few people who gave me the only response that helped, which was “I’ve been there too.”

I thought that for this post, I would use one of the photographs I took at Stonecoast, of a stone wall.

It fits the mood of this post because it shows the cold monochrome of winter. But the truth is that when I took this picture, I was wonderfully, gratefully happy, because I was in an environment that was all about writing. I suppose that contradiction is appropriate . . .

January 26, 2013

Inner Countries

Do you have inner countries? I’ve always had them. I’ve always been able to go to other countries in my mind.

I remember the ways to reach them (because there is always a journey). Sometimes you have to climb over the mountain ridge before you see the valley. Sometimes you have to wait on the shore, until the boat shaped like a swan comes for you. It takes you to the island, and the castle. Sometimes all you have to do is step into the tapestry and find your way through the forest. (You will find your way, because you’ve been there before.)

I wonder if we are born imaginative, or become imaginative by circumstance? I think it’s a combination of both. It made a difference for me that I was a shy, dreamy child. When other children were playing kickball at recess, I was reading. My mind became populated by the things I was reading about, but there was also a consistency to my imagination, to the countries I had inside me. They were based on the fundamental premise that the world was alive, that animals and trees could communicate, that even rocks had things to say. That the true things were the old things: cottages made of stone, and ancient books — mountains, seas, and the great sky above. And that the world was filled with magic: shoes that took you wherever you wanted to go, mirrors that showed you whatever you wanted to see. I think J.R.R. Tolkien would say that my countries exist in Faerie, which he describes as the state in which magic can happen.

Of course, they still exist: I still have those countries inside me. Nowadays, I don’t visit as often as I used to. I have work to do, and there’s not as much time for dreaming as there used to be. But because I have them inside me, I’ve never accepted a simulacrum, a false country of the imagination. I don’t play video games. I barely watch television, and when I do, it’s because a show reminds me of the true countries of my imagination. They’re created by people who have true countries inside them as well, or so I believe. I would rather live in this world, and find in it places that remind me of those countries: I would rather have reality, and glimpse in it pieces of the countries I’ve known since a child. (I see pieces of them quite often: a stream running under a bridge, a horse standing in a field, a tangle of wild roses . . .) And since I am an adult, and a writer, I have the power to bring parts of those inner countries into this one — to write about them, or make them manifest in other ways.

I think that’s part of the writer’s, and more generally the artist’s, task. To bring his or her inner countries into reality, whether by showing where they exist in our world or describing and therefore creating them. Art changes our perceptions, which changes our reality (because our experience of reality is so fundamentally determined by our perceptions). The way an artist describes a copse of birches can change those birches for us.

When I see a copse of birches in winter, I can see the women sleeping inside them . . .

January 24, 2013

The Unsafe Life

I was struck, recently, by a contrast.

I have a friend named Joe. Except that Joe is not his real name. In fact, he doesn’t exist: Joe is a composite of various people I’ve know. But he’s a convenient example.

Joe’s a big guy, about twice my size. If you put him in a movie, he would be either the martial-arts expert hero or the martial-arts expert villain. He lives in a small town in the South, and he owns his own business. Let’s say he’s in construction. He builds things, makes things, some work that gives him a relatively steady and reliable source of income. He has a home, a family, a community. If he wanted, he could live exactly as he is living for the rest of his life.

How do I know Joe? I’m pretty sure we went to high school together. Or not, it doesn’t much matter. He’s just an example, remember.

What struck me recently, rather hard, is that of the two of us, I’m the one who lives an unsafe life. I don’t mean physically, although I live in a large city and regularly receive reports of local robberies from the university police. No, I mean in another way.

I’m the one who ended up going to law school, working as a corporate lawyer. There were days when I got on a plane in the morning, and got on another plane at night. I made telephone calls that moved millions of dollars around the world. It was a world in which the stakes were high, the responsibilities great. And I left that world for the even less safe one of being a writer and scholar. Less safe because after all, corporate law had been a path. If you followed the path, you would do well. But a writer and scholar has to create her own path. She is rewarded for her originality, her insight — her ability to say what has never been said before. To shed light.

I don’t think I ever expected to be where I am today: teaching at one of the largest research universities in the world, whose freshman class is larger than the entire population of Joe’s town, and in a well-known MFA program. Publishing steadily, being respected as a writer. But it’s difficult too: I am responsible for performing, for producing. Standing up in front of sixty students a day, showing them what they did not know before. Flying to conferences, speaking on panels, reading my stories. Delivering new stories, hopefully (but not always) by deadline. There is a point at which people ask you to do things not because you have the right training or skills (like a corporate lawyer), but because you’re you. Because they want a Theodora Goss story. Which is wonderful — but which also means being an artist, doing the work to become an artist, always questioning yourself. Always pushing yourself. Getting better, going deeper. And, of course, accepting criticism, because you’re out there. Presenting yourself to the world.

If I make it sound hard, that’s because it can be very hard. At least for someone like me, who is an introvert and would love to dream her life away, maybe reading books or planting a garden.

I have no idea what the future will bring. Sometimes I sit in my apartment in this great city at night, and feel afraid. And sometimes I envy Joe’s life. It seems so peaceful, one day essentially the same as another. He can grow a garden. He can read for fun. But I realize, looking at my own life, that I’ve always chosen the more difficult path, as though by instinct. The path of greater challenge, and greater freedom. I’ve always gotten on the plane and taken off, to wherever I’m going.

I’m not quite sure why. I think it has to do with the fact that I’m an artist. I think perhaps living an unsafe life is the only way to create art.