Theodora Goss's Blog, page 20

September 29, 2014

On Middle Age

Goodness, I suppose I must be middle-aged. By which I mean that I’m in my 40s, and that’s what they call middle age, right? It’s supposedly somewhere in the middle . . .

Although my grandmother lived to 96, and I’m not halfway there yet. And I don’t feel as though I’m in the middle of anything. One of the problems of being an artist is that you feel, always and for all time, as though you’re at the beginning, just getting started. You don’t think Picasso sat around thinking, “I’m in the middle,” do you? No, he was always at the beginning of another period, of discovering the way to paint. Sometimes I beat myself up mentally, asking myself, why haven’t I accomplished anything yet? Why am I still at the very beginning of writing? And then I remind myself that I’ve been at this ten years, that I’ve published four books. Oh, but those were poems, stories, essays, I think. Not a novel, not yet. And anyway, I’m still learning . . .

Every night, when I sit down in front of the computer and write a new sentence, I learn something new. Every sentence is a beginning.

So perhaps middle-age means physically? But I feel healthier than I’ve ever felt in my life, more fit both physically and mentally. I have back problems, but those started in my twenties, when an Evil Partner at my law firm cast a curse that kept me revising documents for the financing of a technology startup, twelve hours a day. After a week, I couldn’t move my neck. When I went to see the doctor, she told me it looked as though I had been in a car accident. Ever since, I’ve had back problems. So I go to a magical Physical Therapist, and I exercise, and try to get enough sleep, and manage as best I can. I will never get rid of the underlying injury.

The strange thing about writing a blog is that I can remember back, two years ago, when I started this one. I was still working on my doctoral dissertation, then. I remember writing about butterflies, and how when they are in the chrysalis, they must feel as though they’re dying. I wrote that because I felt that way myself, at the time. I had faith, then, that I would emerge at some point, and that what I would emerge as would look like a butterfly.

And guess what? I feel like a butterfly. A very tired butterfly, sometimes. But free, and beautiful, and able to do all sorts of things I could only dream about, when in the caterpillar stage of my twenties and thirties. Like, you know, fly . . . So whatever age I am now, whether middle or something else, thank goodness for it.

This year, several people I knew died, in their thirties or forties. What was the middle for them — their teens? Twenties? The truth is, we don’t know what the middle of a life is. We never know. So I’ve decided that middle age is like fairies, or the stock market — it exists only if people believe in it. I’m not sure I do. (At least, I’m more likely to believe in fairies . . .)

If I had to describe the way I feel, today, the day before my birthday, I would have to say that I feel as though I’m in my late childhood. Just emerging from the process of learning who I am, for the first time confident enough to say “I think I know.” Not yet confident enough to say “I know,” but I don’t think I’ll ever get there, because I keep changing. As do we all. We have a tendency to discount how much we change, how much life changes around us. We think the present is it, that in the present we have arrived somewhere. But we haven’t. We don’t arrive anywhere until our deaths — everything else is journey. And where we are on that journey . . . we just don’t know.

Personally, I intend to live until I’m a hundred. And I intend to write all the way. Perhaps by the time I reach my 80s, I’ll know what I’m doing.

This was me last weekend, out in the country visiting Fruitlands, the farm where Bronson Alcott and his family tried to create a rural utopia. It didn’t work very well . . . But it makes for a wonderful visit in fall, when the trees are starting to turn yellow and orange and red, and the apples are hanging on the trees. And then there was apple pie and maple walnut ice cream. A wonderful way to spend a birthday . . .

September 25, 2014

Telling Stories

In a blog post called “The Storyteller’s Art,” Terri Windling included a wonderful quotation from Philip Pullman:

“[T]here was a sort of embarrassment about storytelling that struck home powerfully about one hundred years ago, at the beginning of modernism. We see a similar reaction in painting and in music. It’s a preoccupation suddenly with the surface rather than the depth. So you get, for example, Picasso and Braque making all kinds of experiments with the actual surface of the painting. That becomes the interesting thing, much more interesting than the thing depicted, which is just an old newspaper, a glass of wine, something like that. In music, the Second Viennese School becomes very interested in what happens when the surface, the diatonic structure of the keys breaks down, and we look at the notes themselves in a sort of tone row, instead of concentrating on things like tunes, which are sort of further in, if you like. That happened, of course, in literature, too, with such great works as James Joyce’s Ulysses, which is all about, really, how it’s told. Not so much about what happens, which is a pretty banal event in a banal man’s life. It’s about how it’s told. The surface suddenly became passionately interesting to artists in every field about a hundred years ago . . .

“In the field of literature, story retreated. The books we talked about just now, Middlemarch, Bleak House, Vanity Fair — their authors were the great storytellers as well as the great artists. After modernism, things changed. Indeed, modernism sometimes seems to me like an equivalent of the Fall. Remember, the first thing Adam and Eve did when they ate the fruit was to discover that they had no clothes on. They were embarrassed. Embarrassment was the first consequence of the Fall. And embarrassment was the first literary consequence of this modernist discovery of the surface. ‘Am I telling a story? Oh my God, this is terrible. I must stop telling a story and focus on the minute gradations of consciousness’ . . .

“So there was a great split that took place. Story retreated, as it were, into genre fiction — into crime fiction, into science fiction, into romantic fiction — whereas the high-art literary people went another way. Children’s books held onto the story, because children are rarely interested in surfaces in that sort of way. They’re interested in what-happened and what-happened-next.

“I found it a great discipline, when I was writing The Golden Compass and other books, to think that there were some children in the audience. I put it like that because I don’t say I write for children. I find it hard to understand how some writers can say with great confidence, ‘Oh, I write for fourth grade children’ or ‘I write for boys of 12 or 13.’ How do they know? I don’t know. I would rather consider myself in the rather romantic position of the old storyteller in the marketplace: you sit down on your little bit of carpet with your hat upturned in front of you, and you start to tell a story.”

I read this and immediately thought, YES. I want to tell stories, that’s what I’m doing . . . telling stories. All of my stories are, actually, stories in which things happen. Important things: people die, countries are born. In other words, they have plot. Shhh . . . plot can be sort of a bad word nowadays. And I understand why, because honestly, a story that is all plot, with little else going on, is rather dull. Who cares what happens when we don’t understand where we are, who the characters are. When the story is written in a purely utilitarian way. But I like to have a plot, and I actually think plotting is an important part of the storyteller’s art. I want my audience to go, “Wait, and then what? What happened next?” I want to keep you awake reading the next chapter . . .

Pullman’s distinction between surface and depth seems important to me. I value art that has both: Van Gogh and Virginia Woolf, where the surface has texture and interest, and the depth has passion and incident. Mastery is being able to work both at once: to create an art that has both surface and depth.

And that, dear reader, is exactly what I’m trying to do. Plot and setting and character and theme and style. All at the same time, like a juggler of golden apples.

This, of course, is Van Gogh’s Irises . . .

September 23, 2014

Following Your Road

I keep seeing articles of various sorts about “Finding Your Purpose.” I think they’re about the wrong thing.

Nowadays, we’re all supposed to find our purpose in life: the fundamental reason we were born, the thing we are supposed to do. I think some people have a purpose, but most people don’t. If they had a purpose, they wouldn’t have to find it — a purpose isn’t something you find. It finds you.

I have a purpose: I don’t remember a time before I knew that I was a writer. My first published poems are from high school, in the high school literary magazine. I published poems and short stories in the college literary magazine. I was in a literary and debating society. I was an English major. In law school, I worked on a novel at night and published poems in a professional poetry journal for the first time. While working as a corporate lawyer, I wrote poetry while eating lunch and hid novels in my desk. When I realized that corporate law would never allow me to write seriously, I quit a job in which I was making $100,000 a year (that’s not a typo) the month after my last student loan was paid off. The month after that, I started graduate school. That year, I lived on a $10,000 stipend.

Having a purpose makes things easier in some ways. It immediately sets your priorities. I knew the important thing was for me to learn as much as possible about English literature, so I went to graduate school. Making money was . . . not even secondary. It was nothing, if I could not write. My law firm was full of people who didn’t particularly want to be there, but they didn’t know what else they wanted to do either. So they stayed.

No, if you have a purpose, it will find you. It found me young — it might find you later in life. A purpose has its own timetable, its own agenda.

What you want to do, in the meantime, is follow your road. I think that’s a lot easier than finding a purpose. With a purpose, you think, is this it? Or this? And of course it’s not, because if it were, you would know. But a road . . . you’re already on a road. Now you have to decide whether it’s the right one.

I think we each have a road, and I think we know whether it’s the right road. I think we can sense it. Have you ever been on the wrong road? Been in the wrong town, profession, relationship . . . You knew, didn’t you? You either knew and admitted it to yourself, or knew and hid it from yourself, but secretly knew underneath. You could feel the wrongness. I think following the wrong road makes you feel sick. That’s how I felt when I was a corporate lawyer. I knew it was a road I had not chosen for myself, an road I was following because other people wanted me to, because they very much emphatically did not want me to follow the road I knew was right. I felt that wrongness the day I arrived at law school.

The thing about your road is, it’s not always easy. It’s not always straight. Sometimes, you will twist your ankle on the stones. Sometimes, you will fall in the mire. But that road is always yours. You may sometimes doubt it, or hate the lessons you’re learning along the way. But it will feel authentically your own. Even the lessons you hate will feel like your lessons. You will own that road. You will own the doubt and wrong turns. And sometimes those wrong turns will lead you right. Sometimes they won’t, and you’ll make mistakes, and have regrets, and feel a sense of shame. But those will be your mistakes, and regrets, and shame. At least you won’t be feeling anyone else’s.

Your road may look completely different than what anyone else thinks it should look like. You may have to say, “But it feels right to live on an organic farm,” or “But I want to be a senator,” or “I know, I never thought I would be writing comic strips either, but here I am.” Or raising sheep dogs. Or raising kids. Or running a hardware store. Who knows — well, you do, or you will, once you get there. The thing about a road is, it’s not a destination. You may only be able to see a few steps ahead at some points. You have to trust your instincts, that feeling in the pit of your stomach. If you can only see a few steps ahead, well, take those steps. Maybe then you’ll be able to see a few more steps . . . And you have to be honest with yourself about whether or not it’s your road. No lying, no “It’s a perfectly good road, and my parents like it, and my friends like it, and everyone approves of me being on this road, so it must be the right one.”

I honestly don’t think you can live a meaningful, fulfilling life walking anyone else’s road.

Somewhere along that road, you may encounter your purpose. Or maybe not. But you’ll be traveling along a road, and the road will be yours. And that’s the important thing.

This is me on the road behind the Stone House, at the Stonecoast MFA Program, where I was teaching this summer. That day, it felt like my road, the road I should be walking along both actually and metaphorically. I owned that road . . .

September 21, 2014

Learning to Decorate

I’m decorating my new apartment. It’s not that new anymore, actually — I moved in June, but then I immediately went to a literary convention, and then to teach up in Maine, and then I had a few weeks to unpack before I went to visit family in California. And then the semester started. So it’s really only been in the last month that I’ve been able to decorate. This apartment is larger than my last one, so decorating involves buying new furniture or refinishing old furniture. Which takes a while . . .

I never learned how to decorate as a child. I think some people do — they watch their parents put together rooms, and get a sense of what rooms should contain, what they should look like. What makes for a comfortable, beautiful space. But I didn’t learn that, I think for two reasons. First, I was growing up in the seventies, when ugliness seemed fresh and new. No, really — isn’t that what happened? After the sixties, beauty and comfort seemed old, done — and worse, reactionary. Art and architecture embraced the ugly, which at the time seemed powerful. It seemed to make a statement, although I’m not sure anyone actually knew what it was saying. Now, in retrospect, it just seems sad: those hideous sweaters and sweater-skirts, sweater-pants. (If you grew up in the seventies, you know what I mean.) On my university campus, the law school was once a famous example of Brutalist architecture. It’s now being entirely rebuilt, partly because it turned out to be impractical to actually use, but partly because no one wants to look at it. And the same sort of thing happened in decorating.

The second reason was that I grew up with a mother who prefers the modern and minimal: no curtains, a bed that is essentially a box. When I was in Middle School, I was put into a class called Home Economics that really should have been called Reinforcing Gender Stereotypes. (The other option was Shop, in which all the boys built things.) One assignment asked us to take a cardboard box and decorate it, as though it were a room in a doll’s house. I failed the assignment because my room was modern, minimalist. I lost points for the lack of curtains, for having almost no furniture. But our house had no curtains either . . . I fought against that minimalism in my own way. In my room, I put up bed curtains, bought Laura Ashley sheets. I wanted to be romantic (I was a teenager, after all), and so I wanted my room to be romantic. It’s hard to create a romantic modern, minimalist room . . .

I learned to decorate as an adult, the same way I’ve learned most things in my life: from books. I always cared about my living spaces, always thought of them as extensions of myself. And so I bought decorating books. I would flip through them in the bookstore, picking out the ones whose pictures made me go “Yes, that.” They had titles with words in them like “mission style” and “shabby chic” and “cottage.” And I started to create my spaces, buy the furniture that would go in them and that I would carry around with me, from space to space. The curtains, the pillows, the paintings.

I believe, more strongly than ever, that the spaces we live in are important: that they should be comfortable and beautiful. They should help us become, and function as, who we are. And I believe in saving money as much as possible, in doing as much as one can oneself. Which is why I sometimes have paint on my clothes . . . This week, I painted a bookshelf, a chair, and a mirror. You can see them all being painted here:

I chose the color some time ago: it’s called Flax, and it’s a cream, but not a warm cream. Almost a beigy cream. It echoes the beiges and creams that are the basic color scheme of the apartment. The shelf was already that color when I bought it, and just needed some fresh paint to cover scratches and wear. The mirror was a cheap hardware store mirror I had bought, originally stained brown and with that shiny cheap furniture finish. I wanted it to look old, like a mirror I could have bought in an antiques store, or that my grandmother had given me. So I painted it Flax. It makes me much happier now, and looks just right in its corner of my bedroom, in front of the shelf.

The entire space is a work in progress, but I’ll show you what my living room looks like. It took a long time to learn how to decorate, because it was a process of learning not just how to put together a room, but of learning myself — my own tastes, what would make me happy. What would fit how I lived and what I needed. If a room, a house, doesn’t fit the people who live in it, it’s decorated wrong. So this is my taste, which might not be yours . . .

I love my red curtains, which I bought at a home good store. They were the cheapest and simplest I could find, all cotton so they can be washed in a machine. I’m not a fan of anything requiring special care. You can see the paintings lined up by the shelves, waiting to be hanged. But I’m not sure where to put some of them yet. And my favorite Victorian slipper chair, which I bought at an antiques store, is covered with a sample of the fabric in which I will eventually have it reupholstered.

My small table, which I refinished, with the chairs I reupholstered myself. You can just glimpse the chair I was repainting behind the table. I found it, battered and needing care, in a thrift store. It looks so lovely now . . . And my birdcage, with birds on the outside. (They always go on the outside.) The bolt of fabric in the corner came just this week. I’m going to sew it into pillows for the daybed (not pictured because it’s on the other side of the room, and also being repainted).

And one of my desks (I have two), both of which I refinished. This is the one where I prepare to teach — the other is the one I write on. The wall is still waiting for more pictures. And did you notice? I not only have curtains, I have two sets of curtains (three windows, six curtains in all). I think I have, at least, mastered the curtains part of decorating . . .

September 18, 2014

Dealing with Envy

If envy turned you green, there are days I would look like a cucumber.

At the moment, I’m reading Dani Shapiro’s Still Writing: The Perils and Pleasures of a Creative Life. In it, she talks about how difficult writing is: how you sit down each morning in front of the blank page, and you have to fill it. She describes her writing routine, which involves writing in the morning, revising in the afternoon, in a room of her house in rural Connecticut. And I find myself envying her.

This is what my writing routine looked like yesterday: In the morning, I got up and prepared for class, which involved grading the papers I had not gotten to the night before. I went over my lesson plan, made sure I knew what I would be talking about that day. Then I taught my morning class. Back for lunch and to drop off my laptop. Then I taught my two afternoon classes. Then I went directly to physical therapy — usually I would have office hours, but it was the only time this week I could schedule an appointment, so I moved my office hours to another day. The physical therapy helps me so much — makes it so much easier for me to do my teaching and writing — that I don’t want to miss a week. Being able to write without back pain is a wonderful, wonderful thing!

Then I had time to run to the grocery store for oatmeal and sugar, and when I got back, it was time to Skype with one of my graduate students. Then dinner. Then a bath. And then, finally then, at about 9 p.m., I sat down in front of my computer, honestly feeling a sense of despair because I had not been able to write for about a week — all the other days had been even busier. Finally, I had time to write, and I didn’t even know if I wanted to.

But I started anyway, because one of my mottoes is “Do it anyway.” So I started, and then I was up writing until midnight, because once I started, I didn’t want to stop. I need to get back to novel revisions, but first I need to finish all the administrative work that one is given at the beginning of any semester. I’m almost done, but in the meantime, I wanted to write something else to clear my head — so I’m writing a fairy tale, called “Red as Blood and White as Bone.”

But envy . . . I envy other writers their time, their space, their financial resources. Their awards.

The way I’ve found to deal with envy is to tell myself, quite sternly, “All right, you can have everything she has. But you have to be her. Do you want to be her?” And when I think about it, I realize that I don’t. Do I want to be Dani Shapiro? No. She seems lovely, but no. Her childhood was a mess, and while my childhood was a mess too, at least it was my childhood, my mess. Would I have wanted to go to Sarah Lawrence, then get married and live in rural Connecticut? Sure, I hated law school, and sure, it was difficult getting through my PhD. But the furniture of my mind includes Alan Dershowitz and Derrida, and I would not trade that furniture. Not even for more comfortable furniture.

I want to be the writer I am, not the writer she is, even if that means being less successful. Even if it means working very hard, and being tired all the time. And trying, day after day, to find the time to write . . .

There is a day, in the life of every writer, when you realize that you have to cut your own path through the forest. That day, you look at the trees in front of you, and you feel your heart sink with despair. Because you just don’t think you can do it.

And then, you start to do it anyway. One tree at a time, one word at a time.

September 16, 2014

Accessorize Accordingly

“Remember who you are. Accessorize accordingly.” –Justine Musk

I love this quotation from the fabulous Justine Musk. It sounds like fashion advice, but of course it’s more than that. It’s life advice.

The first part says, remember who you are. Not discover who you are, but remember . . . because you are that already. You may have forgotten it (have you forgotten it? I bet you have, even if only a little.) I forget who I am sometimes. I think, I’m a teacher and a mother. Which is true, but those are not who I am: they are what I do. I teach, I have a daughter. But who am I when I am not teaching, when I am not with my daughter? And at other times I think, I am tired, or I am lonely, or I’m in the dark. But those, again, are not who I am. They are temporary states.

So who am I, at my essence, in my core? I am a storyteller. I am a sorceress whose magic is words. I am those things even when I am a teacher, or mother, or tired, or lonely . . . You get the point. What are you at all times and everywhere? That is what you are. All the other things are only partial, or only temporary. What you want to remember, and keep remembering, is the core.

And then, accessorize accordingly. We usually think of accessories as small, almost trivial things: jewelry, perhaps a purse or hat. But we know, or at least those of us who care about such things know, that accessories make the outfit. And of course the word has a use outside of fashion: you can be an accessory to a crime. An accessory is something that helps, or supplements, something else. So who are you, and what will help you be that, stay that, remember that?

I think material things are very important. We ourselves are material, made up of the same elements that make our world. And the material affects us: whether we live in a beautiful place, whether we can wear comfortable clothes, whether we have access to healthy food. I think the phrase “accessorize accordingly” means decorate your life, choose the material elements of your life, in a way that reflects and reminds you of who you are.

So, you know, if you’re a sorceress . . . dress like a sorceress. This is me dressed to teach class, but I call this outfit “Sorceress in Disguise.” If you have the eyes to see it, you’ll see who I really am.

So, who are you? Remember, and then make your material life reflect who you are, deeply and essentially. Dress as who you are, furnish your home for yourself (not someone else’s idea of you). I think that has two important effects: first, it keeps you from having too many material things, because although the material is important, we overdo it, don’t we? It’s because we don’t know who we are, and try to be different selves by buying them. But that never works. And it helps you remember. You can stand in front of a class talking about grammar, but underneath you will know: I am a sorceress in disguise, a storyteller whose words are magic . . .

September 14, 2014

Crossing Thresholds

I redesigned my website. Did you notice?

Well, not redesigned exactly, but changed the images, changed some of the organization. I’m also updating the pages.

I suppose it’s because I feel as though I’ve crossed yet another threshold. And now I seem to have arrived somewhere, although I’m not sure where yet. It feels stable, it feels secure, although after the last few years, I don’t quite trust security. After all, we’re on a planet hurtling through space, orbiting around a sun that is itself hurtling through space. Solid ground is an illusion.

But at the moment, the illusion feels rather nice, and I think I’ll believe in it for a while . . .

I spent this summer traveling: in June I went to Budapest, in July I went to Readercon and then to teach at the Stonecoast MFA Program residency. In August, I went to Los Angeles and San Francisco. At some point, I moved into a new apartment, and it sat furnished but undecorated for most of the summer while I crossed over the Atlantic and said hello to the Pacific. I love traveling, and I love living out of a suitcase. But it feels nice to be in my own apartment, which is already almost decorated. It feels nice to have my own furniture, and my clothes in the closet. It feels nice to know where all the dishes are.

We have a tendency to think that whatever we’re living through at the moment will continue forever: if we’re in crisis, we think we’ll always be in crisis. If we’re in a period of stability, we think the floor is solid and will never start shaking and cracking under us. But life isn’t like that, is it? It has its tides, just as the sea does. It’s a continual process of crossing thresholds and entering new rooms. The writer Elizabeth Gilbert said something recently that has stuck with me: she said, we are told to find balance in life, but finding balance means that most of the time, we’re off balance. We only ever achieve balance once in a while. That perfect equilibrium is always elusive, always dependent on our leaning first one way, then the other.

And honestly, we have to lean, because that’s the only way to dance. I think, here, of a ballerina: she maintains the illusion of balance, that perfect en pointe, but she’s only ever balanced for a little while. Otherwise, she’s always in motion, always leaping and turning. As we are. As is this entire planet, spinning through space.

I don’t know where I am yet, but so far I like it here. It feels as though there’s a lot of work for me to do, and of course not enough time to do it in, because when is there ever? But for now, there’s a floor under my feet, and a soft bed, and food in the refrigerator. I’m going to put pictures up on the walls, and paint the cabinets. I’m going to see what work I can do that is worthwhile. Because in the end, that’s what matters. I’m sure there will be more thresholds in my future, more leaping through space. But for now, this feels nice. I think I’ll stay . . .

The new images on my website are photographs I took at a nature conservancy near Concord, Massachusetts. It’s a wetland, and when I visited, the lotuses were blooming — acres of them. They were like sunshine on the water, under a cloudy sky . . . And the photo above is of me among the cattails. I’m not short, I assure you. But the cattails were very tall.

September 12, 2014

Being Hypersensitive

Recently, I tried a new face cream. Big mistake. Within three days of starting to use it, I had a red rash across my face. I’d been so careful, too: I’d read all the ingredients, and nothing looked irritating. But there was the rash, red and itchy. I could mostly hide it with foundation. It went away in a few days, and my face looks normal now, but lesson learned. I have to keep reminding myself that I’m hypersensitive.

I didn’t understand that when I was young, which made life more difficult than it probably should have been. But when I was doing my PhD, I came across Elaine Aron’s The Highly Sensitive Person, and later I read Sharon Heller’s Too Loud, Too Bright, Too Fast, Too Tight, and in both I recognized aspects of myself.

What does it mean when I say that I’m hypersensitive? It means that when I buy creams and cosmetics, I look for those that say “for sensitive skin,” because I tend to react badly to certain chemicals. Like, Red Rash Zone. But I can’t go without face cream either, because I burn easily, and even the wind will make my skin red and itchy. I need to protect it. And natural products are often even worse than what I can buy in an average drugstore — Mother Nature, much as I love her, is a treasure house of irritants and allergens. I don’t react as badly as some people I know: I can wear perfume just fine, although strong smells bother me. As do loud noises. And violence.

Because hypersensitivity manifests itself in all sorts of ways: it means, I think, that you have fewer layers of protection from the world than most people. You are more vulnerable to it. This can be a strength: you notice things that other people don’t. If we were in a room, I would probably intuit your emotions, perhaps even what you’re thinking. I would know from the expression on your face, the way you’re holding yourself. But it’s also a weakness. Things that other people find energizing might exhaust you, if you’re hypersensitive. I find theme parks mildly horrifying.

Because I’m missing some of those barriers, I have to build them myself. Some of them are physical: my apartment, which is a sort of refuge from the world, beautiful and soothing. It has thick walls, and soft carpets, and light that filters in through large windows. Books and art and music. Even my face cream is a sort of barrier. But most of them, and the most important ones, are internal. I have to be able to, emotionally and mentally, find a peaceful center within myself, so I can live in a magnificent city, and teach at one of the best universities in the world. So I can interact with sixty students, being there for them without feeling as though I’m losing myself.

I don’t quite know how I build those internal barriers. I didn’t have them as a child, which made childhood incredibly difficult. Imagine if you’re a child, sensing the world so deeply, alive to beauty, but also every criticism. You live intensely — I still do, and I don’t want to lose that intensity of perception. It took a long time to build them, and some of them are unconscious now. (One of them is kindness, and another of them is politeness, and if you don’t know how kindness and politeness can be barriers, then pay attention the next time someone is being kind and polite. Pay close attention to how you’re being shut out.) But I know that those barriers are necessary . . . And I’ve once again learned my lesson about face cream!

August 31, 2014

Travel Lessons

Once again, this summer, I’m recovering from jet lag. I’ve done a lot of traveling . . .

This time, I traveled with my daughter to Los Angeles and San Francisco to visit family. Travel is always a disruption, no matter how good you are at it, and I pride myself on being pretty good. I can sleep in airports if I need to . . . But it’s also always worth it, and I particularly wanted to travel with my daughter, so we could learn together the sorts of things that travel teaches you.

I wanted to go out there in part to see an old friend of mine: the Pacific Ocean. Years ago, during a particularly tumultuous period in my life, I had gone out to Los Angeles to take care of my grandmother, who was living in a house by the beach. Every day, I would walk down to the ocean, and we would have a talk, the ocean and I. It’s a very soothing sort of ocean, more so than the Atlantic, although I’m not sure why. Perhaps because it’s larger, and calmer, and seems older. It’s a very sensible ocean, and puts your problems into perspective.

So of course the first thing I did when I woke up, my first morning in Los Angeles, was go down to see the Pacific.

The sensation of salt water on your feet never gets old, does it? And then, of course, I introduced my daughter to an ocean she had never met before: Ophelia, meet the Pacific Ocean. Pacific, meet my daughter Ophelia. They both bowed politely . . .

So what sorts of lessons can one learn from traveling, anyway?

1. Changing your location can change your perspective.

Being on a different coast, beside a different ocean, can change the way you see the world or your own life, your self. I don’t know who said “Wherever you go, there you are,” but it’s not quite true: the self there may not be the same as the self here. Traveling places changes us. The self is not such a solid, constant, reliable thing that it’s unchanged by location, distance.

I think that’s a wonderful thing, really. If we can see things differently and anew, that means we can change. And we can change our circumstances as well. We are not stuck in one place. Travel involves a kind of optimism: going someplace will be worthwhile, perhaps because it will be interesting or beautiful, perhaps simply because it will be different.

In Los Angeles, we went to the Getty Villa, which has a collection of Greek, Roman, and Etruscan antiquities. My daughter had read the Rick Riordan books, so she knew all the old gods and goddesses, both by their Greek and Roman names. It was lovely to see a ten-year-old wandering around a museum where she felt completely at home, although she did ask me at one point, somewhat exasperated, if we would ever get to the end of the naked people. No, I told her, because the Greeks and Romans thought the human body was beautiful. Which was met with a typical ten-year-old eye-roll.

The nice thing about the Getty is that the villa is built like a Roman house, with inner courtyards. It’s lovely to wander around under a blue sky, in the cool coastal air.

2. You must see what you can, when you can see it. In other words, carpe diem, because you’re only passing through.

We weren’t in Los Angeles for that long, so we had to decide what we wanted to see. The Getty Villa of course, and the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, which has a wonderful collection of dinosaur fossils. I wish we could have gone to the Huntington Botanical Gardens, but there simply wasn’t time. And then we were on to San Francisco, where we went to an exhibit of skulls at the California Academy of Sciences and had tea at the Japanese Garden. The skulls were for Ophelia, the tea and garden were for me.

Again, there simply wasn’t enough time to see everything we wanted to in San Francisco. But we did the most important things, which were spend time with my brother, who introduced Ophelia to Speed Racer, and get a sense for one of the great cities of the world. I hope we can go back . . .

Life is like traveling, of course. (You knew this was a metaphor, right?) You’re passing through, and you don’t know how long you’re going to be here, so see what you can while you have the time. And do what you can, which brings me to the third lesson:

3. Experiences are more important than things.

There’s something refreshing about living out of a suitcase. You realize how little you actually need . . . We traveled with one suitcase between us, with our clothes and toiletries, and a carry-on bag each for our laptops, books, whatever we would need on planes. Whatever we could not replace or do without. Don’t get me wrong, I love my closet full of clothes, but I know that I don’t need them. And although I would not give up my pretty china, I can live very well, comfortably and even elegantly, with a mug, bowl, and plate, as I did for a month in Hungary.

Doing is more important than having. In California, we walked on the beach, watching the sandpipers running back and forth. We ate inordinate amounts of ice cream. We ate crickets. (No, really, we ate crickets. They were sold in packets at the Natural History Museum, and Ophelia wanted to try them, and then of course I had to try as well. Because I couldn’t let her be the only one to eat crickets, could I? I would never live that down.) Back in Los Angeles after our trip to San Francisco, we got henna tattoos to commemorate our trip: a butterfly for me, a dragon for her. Our last day in Los Angeles, we wrote our names on the sand, knowing they would disappear, as the henna tattoos will in a couple of weeks (although right now they are still there, brown designs on our arms.)

It’s the things we do that we remember the most.

4. It’s good to come home.

Home isn’t a place you have. It’s a place you make. It’s good to make a home, and then travel away from it, and then come back to it. I write this sitting at the desk in my bedroom, which still needs work: shelves I need to buy and refinish, bed curtains that need to be put up. I moved into this apartment two months ago, and I’m not done decorating. But already it’s starting to feel like home, like a place I can wrap around myself on winter nights. It’s bright and cozy, and it makes me happy to be back.

So my advice to all you travelers, because you are all travelers, on this planet that is itself traveling through space, is: create a home, and then travel away from it so you can change and return, change and return. That’s what the waves do, and that’s what we have to do, because all life moves in cycles, and so should we. As though we were dancing . . .

August 16, 2014

Staying Healthy

Let’s be honest: writing is not particularly good for you, physically. It involves a lot of mental work, but a limited range of physical motions: you can end up sitting in front of a computer for five hours at a stretch. At some point during those five hours, you will get incredibly hungry, and you will eat something, anything, because you need the energy to keep going. Writing is energy-intensive work. So there you are in front of the computer with a bowl of . . . something (in my case, Trader Joe’s raw trail mix, but that’s because I’m trying very hard, and very consciously, to stay healthy). At the end of those five hours, you come to, almost as though you were waking up or coming out of a coma. And you’re not entirely sure what year it is, much less what day. That’s how deeply you can disappear into a story. At that point, you may realize that it’s long past midnight, and you’ve just pushed yourself, and pushed yourself, because the writing was so compelling that you didn’t want to stop. And guess what? You’re going to be a wreck the next day.

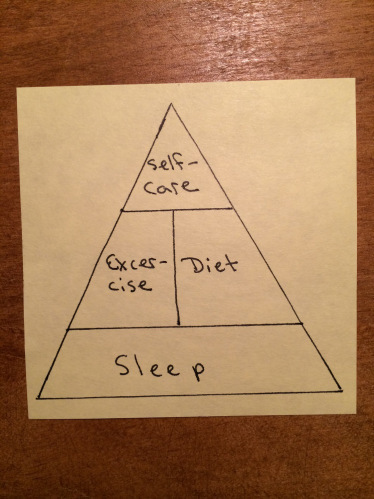

I thought I would write a post on saying healthy for writers, because it’s something I’m working on myself. I mean this very seriously: in order to write well, you must stay healthy. I’ve seen writers develop terrible back and shoulder problems that prevented them from writing. I’m in physical therapy myself: I go once a week. I have a foam roller. (For my back. I roll on it. Not joking.) I’ve gotten into periods where I haven’t taken very good care of myself, staying up until all hours, not exercising, which inevitably leads to eating badly. And my writing has suffered. I write best, and most efficiently, when I’m healthy. So now I have a sticky over my desk. It’s actually a drawing of a pyramid, and it looks like this:

(I know, I’m not an artist. Someone should make a graphic of this, I think.)

It reminds me of the four things that are essential to staying healthy. I’ll talk about them a bit below.

1. Sleep

Sleep is the absolute essential, the base of the pyramid on which everything else rests. When I don’t get enough sleep, I don’t have the energy to exercise and I end up eating more than usual, and differently than usual — as in, a lot more chocolate. You see, chocolate has sugar and caffeine, and both of those things keep me going. When I haven’t had enough sleep, my body says, “Lady, I need energy from somewhere. And you’re going to give it to me, or I’m going to collapse right here, in the middle of the street or classroom.” If you don’t get enough sleep and you end up eating badly, that’s not you eating badly — that’s you giving your body what it needs, which is energy. You just happen to be giving it to your body in the wrong way, a way that is ultimately inefficient.

I used to think that sleep was a waste of time, and that’s why I didn’t get enough — I had a lot to do, and no time to waste. Then I read a scientific study that said the brain is just as active while sleep as it is while awake. So what is it doing? Scientists aren’t entirely sure, but the brain seems to sort through and consolidate knowledge while sleep. Whatever it’s doing, it’s important stuff, and you’re going to be a better writer when your brain is working well. To work well, it needs enough sleep. So now sleep is on my to-do list. It’s one more of those things, like brushing my teeth, that I know I need to do in a day. Whatever it’s doing to my brain, I think it makes me a better writer.

2. Exercise

I’ve written about exercise before, in a blog post on forming habits. So you may know that I exercise every day, for about twenty minutes, in a routine that includes pilates, yoga, and stretching. It doesn’t require any special clothes or equipment. I do it barefoot, in pajamas, in my living room. First thing. For me, it’s a necessity because if I don’t, my back problems get worse. But I think if you’re writing for any length of time, intensely, you have to exercise regularly or you’ll develop serious physical problems. We know, now, that sedentary jobs and lifestyles are dangerous to your health, and writing is the ultimate sedentary job. I’m lucky that my non-writing life involves a lot of movement: I live in a city, so I walk or take public transportation everywhere. I teach, which means that at least while I’m teaching, I’m always on my feet — although meeting with students and grading papers both involve sitting. But I try to be as active as I can, and to take breaks when I write — stretch, change my position, walk around for a bit.

For me, twenty minutes a day, every day, is a minimum. And I know that if I don’t, I’ll start having physical problems . . . Back pain is a pretty good motivator, for exercise!

3. Diet

By diet, I mean the food you eat every day — your ordinary, everyday diet. I find that diet affects my health as much as exercise — specifically in terms of energy. If I eat badly, I don’t have the energy to do the things I want to do — the teaching, the writing, even the staying in touch with people. I need to eat frequently enough (every couple of hours, for me), and I need to eat the right things: whole grains (whole wheat bread and pasta, brown rice, oatmeal), lean protein (meat, cheese and other dairy products), vegetables (lots of these!), and fruit. Usually I try to get whole grains and lean protein at every meal, and then as many veggies as often as I can. And some treats: nuts and dried fruit, dark chocolate, Whole Foods fudge bars. And sometimes, total blow-out treats, like chocolate cake! But not that often . . . (You need the blow-out treats. See “self-care” below.) And I do watch my calories, but the most important thing is to eat real, healthy foods often enough that you’re never really hungry. Because if you are, you’ll head straight for the chocolate.

And I have a trick for the writing munchies. I’ve made a rule for myself, which is that I don’t eat in front of the computer. This is ostensibly because it’s not good for the computer, but really it’s not good for me. I trick myself by drinking flavored fizzy water while writing. This feels to my body as though it’s getting something, but really it’s getting water — which is good, because it means I’m also drinking water, which is another thing I forget to do. Unfortunately, I haven’t managed to convince my body that it’s getting anything with plain old tap water, I suppose because it has no flavor — it would be so much cheaper! But if I have a long writing day ahead of me, I stock up on fizzy water, usually raspberry and lime flavored. I know, it’s silly, but there it is . . .

The thing is, we’re all different, with different bodies, and we need different things: you need to find out for yourself how much sleep you need, how much and what type of exercise, how much and what type of food. Experiment. Figure out what makes you feel healthy, what gives you energy. What makes you feel your absolute best. What works for me may not work for you. But I can guarantee that you’ll need to pay attention to sleep, exercise, and diet. And that if you do, the writing will go better and easier.

4. Self-Care

The last item on the list is self-care. I’ve tried all sorts of different words for this category, and can’t find one that really encompasses what I mean. What I really mean is “Being Nice to Yourself,” but that’s cumbersome, isn’t it? I mean taking care of yourself, however you like to be taken care of. My favorites are taking bubble baths, buying myself flowers, meditating. Going to see beautiful things, like art museum exhibits or ballets. And making sure that each week, I get in a blow-out treat, with lots of fats and sugars. Usually cake. But it has to be absolutely delicious, and I have to enjoy every bit of it — that’s the rule.

I tend to forget things if I’m not reminded of them, especially things like taking care of myself. So it’s useful to have the Staying Healthy pyramid up on my wall, where I can see it. And then I can ask myself what I’ve done for myself that day, whether I’ve remembered to treat myself well. Because, obviously, there’s one person I’m going to have to live with for the rest of my life, and that’s me. If I don’t treat myself well, I’m going to suffer the consequences. And honestly, it’s going to be harder for me to treat anyone else well either, because I’ll be moody, and vaguely angry, and just generally out of sorts with the world. I need to be physically healthy to be psychologically healthy, too.

But really what I’m focusing on here is the writing. I need to be healthy to write well and efficiently. Which is why, since it’s almost 11 p.m., I’m going to sleep . . .

(This is me being thoroughly urban, running around the city on an ordinary day. And feeling very healthy . . .)