Theodora Goss's Blog, page 12

March 6, 2016

Victorian Virtues

Recently, I bought boot polish.

You’d think I would be the sort of person who has boot polish. I mean, I have silver polish. I have dusting cloths. I have an entire sewing box, with a button collection. Remember button collections? Our mothers and grandmothers used to have them, and we used to take them out, look at the buttons, wonder where that one button shaped like a ladybug had come from. We used to let the buttons pour through our hands. I even have a tool box, with a hammer and different types of screwdrivers, so this isn’t about having the domestic tools associated with one gender rather than the other. I just, for some reason, didn’t happen to have boot polish. I don’t know why.

But my boots were looking positively disreputable. In Boston, when it snows the city maintenance workers spread a great deal of salt around. This winter, we’ve had very little snow. At this point it’s all melted, but the other day, while I was walking to the library, I kept seeing white piles. I thought, perhaps it hasn’t all melted yet? And then I realized they were piles of salt. That salt gets on your boots and leaves a white crust, as though the tide had come in and then gone out again — you have a tidal mark on your boots. And that’s how my boots looked: as though I had walked, or rather treked, through a frozen sea. So I went to the drug store, where there is a shoe care section, and bought black boot polish, several different kinds of brushes, and a buffing cloth. Now I have a boot and shoe care kit. As I sat there, on the kitchen floor (with some paper towels down to protect the floor from polish), polishing and buffing my boots, I felt a sense of virtue, and I thought, yes . . . this is what I always read about in Victorian novels. It’s the virtue of careful maintenance.

I don’t remember where I read this story, but it’s about a Victorian man who chose his wife by the neatness of her boot heels. What in the world? you may ask. But, as the storyteller explained, boot heels are constantly wearing down, and if you let them, worn, uneven boot heels will eventually ruin the boot itself. If you maintain the heels, the boots will be wearable for . . . well, a lifetime, but in the case of many Victorian boots it’s really several generations, since they’re so well-made. In a day when boots were much more expensive, relative to the average income, than they are now, boot maintenance, including boot-heel maintenance, was essential. It was the sort of thing that distinguished the thrifty, careful housewife from the other kind.

Nowadays, I often look at the boots left at Goodwill, some of them boots that originally cost several hundred dollars, and what I notice is that there’s nothing at all wrong with the boots. They simply have worn-out heels. Getting heels replaced isn’t cheap. It’s even more expensive if you need to have soles replaced as well, as I did recently: about $45. But that’s still less expensive than buying a good pair of boots. Polishing isn’t as important as getting heels replaced, but it’s part of maintenance. The maintenance of a household and wardrobe also includes polishing silver, dusting bookshelves, sewing on buttons. But these are all Victorian virtues. They seem so old-fashioned now that it’s almost as though they’ve been forgotten. When buttons fall off, people get rid of the garment.

The criticism of these virtues is that they seem so small, so petty. They take time, and often that time is gendered, because it’s usually women who do the dusting, who sew on the buttons or sew up the hems. Women are usually the ones responsible for maintenance and small repairs, although I think it’s still more common for men to polish shoes, partly because men’s shoes are so much more expensive. And yet I want to argue for these sorts of virtues, first because they are part of a culture of care that we seem almost to have forgotten — once, you cared for your things, rather than discarding them when they broke or tore or fell out of fashion. That led to a lot less waste. So these small virtues have larger implications for how we use our stuff, how we related to the larger world around us. Second, I think they’re good for us personally. Caring for your things changes you — polishing boots changes you, polishing silver changes you, sewing on buttons changes you. It makes you a different kind of person, a slower person in some ways, a person who takes time. It makes you feel differently inside, both about the stuff you’re caring for (because maintenance is a mark of love) and about yourself. Third and finally, they lead to beauty and elegance. My boots were a whole lot more beautiful once they were polished. I was proud of how they shone. I wore them proudly, rather than cringing with embarrassment whenever I put them on. I felt that particular satisfaction you feel when everything is in the right place. Now, there’s no reason everyone should eat with silverware, rather than stainless steel. But I love it, and the truth is that it’s cheap if you buy good, old silver plate, and it’s easier to take care of than you would think. I love the sheen of it, less hard than steel, sort of like moonlight.

I’m very proud, now, of having all the right tools to polish my boots. And to sew on buttons. And to do the sort of small maintenance work we all need to do in our lives, which makes our lives better, easier, more beautiful. So, you know, if you haven’t polished your boots and shoes in a while, this is just something to think about. There is, still, some value in those old, and seemingly old-fashioned, Victorian virtues . . .

(The painting is Sunlight and Shadow by William Kay Blacklock. Yes, I know, it’s a romanticized image of a woman sewing! No, I did not look like this while I was sitting on the kitchen floor, polishing my boots. But it still captures perfectly the beauty I associate with small Victorian virtues.)

February 23, 2016

The Overwhelm

I’m feeling a bit overwhelmed.

By the time I get to Thursday, I will have spent an entire two weeks without a single day to myself. There are all sorts of reasons for that, mostly teaching (I’ve been holding student conferences, which sometimes means meeting with students for five hours a day) and Boskone, which was a wonderful convention but also exhausting. I have all sorts of things I need to get done, most of them by the end of the month, and I’m simply overwhelmed with work. I suppose the good thing is that it’s work I want to do: teaching and writing, mostly. But that doesn’t help much when you’re feeling the overwhelm.

That’s what I call it, the overwhelm. It feels like a place I’m in the middle of, as well as a state of mind. It’s a place where I haven’t gotten enough sleep in a long time, and so I’m tired and a bit despondent, and wondering why I’m doing any of this anyway. It’s a place where I doubt myself.

It’s a place where I don’t want to talk to people anymore. Where I just want to curl up in bed, eat almonds and chocolate, and read murder mysteries. Or watch Murder, She Wrote, one episode after another. Anything having to do with people killing other people, and then a clever detective (preferably female) figuring out how and why. I suppose it’s a misanthropic impulse, as well as a sign of empathetic burnout. The last thing I want to do is feel anymore. I want clean, clear rationality, a sifting of clues.

But of course I can’t do that. Tonight I have to prepare for class tomorrow, and I have emails to send. People people people — it’s all about people, isn’t it? It’s all making contact, either in person or electronically. And the truth is that I love people — I find them fascinating. If I didn’t, I couldn’t be a writer. I love teaching: my students are smart and interesting and funny (sometimes unintentionally so), my graduate students are brilliant. But people are overwhelming, for an introvert.

I’ve been an introvert since I was a child. When I was a teenager, I use to have a fantasy: that I could go away and live in the forest, in a castle, and be a sorceress. That would be my job description, sorceress. I would have a magical mirror, in which I could see whatever was happening, all over the world. But I wouldn’t have to participate. I could just stay in my castle . . . I suppose it’s a classic fantasy, for an introvert.

Sometimes I wish I could just write — live in a small house in the forest and write books, stories, poems. That’s the more realistic version of being a sorceress and living in a castle, I suppose. I would still have the internet: that would be my magic mirror. I could watch the world. But I know people who’ve done that, just written, and it’s very, very hard. Hard to eat, hard to pay rent. Not many of us have the luxury of cutting ourselves off from the world.

So what should I do? The only thing to do, really, is to become the forest, become the castle. To do what I have to, participate to the extent I must, but create a space within myself where I can be calm, where I can rest. Where I’m not so worried about getting up, getting where I need to go, that I set two alarm clocks in the morning. I mean, I still need to do that in real life. But there must be an imaginary life I can create where it’s not necessary. And I do have to get to Thursday, when hopefully I can rest just a little, before I start the mad scramble of trying to catch up.

Sometimes I think life shouldn’t be quite so overwhelming, but that’s what happens when you want to be a teacher and a writer. If I were trying to do less, it would all be easier, so really I have only myself to blame. Still, it’s a hard place to be, the overwhelm. Especially when you can’t see when you’re going to get out of it. (Thursday, I tell myself. On Thursday, I’ll get some rest.)

The truth is that I didn’t even want to write this, because that’s more communication, with more people (although you are lovely people, who read this). But I haven’t written a blog post for a while (and this is why), so I thought I should. And also, it’s good sometimes to talk about the things that aren’t working, that aren’t the way you want them to be. I want to do everything I’m doing, but I don’t want to be overwhelmed by it, and I want more than five hours of sleep a night, and I want to be able to do laundry, and shop for groceries. I want to write new stories . . .

This is what it feels like, in the overwhelm. It feels exhausting, and anxious, and filled with doubt. Will I ever be the writer I want to be? Will I ever be able to do the things I want to?

And then, because I’m a big girl, I look at my to-do list and think, one step at a time. Do the things, cross them off, it will get done. Have dinner, rest for a little while, get back to it. Sometimes you just have to keep your head down and do the work. That’s what it’s like in the overwhelm, but there is another side. I remember what it was like, that summer I went to Budapest and lived alone for six weeks, and wandered around the city, and took Hungarian classes. I remember being blissfully happy, waking up in the morning to birdsong in the park and sunlight through the windows. That exists, and I’ll get back there. In the meantime, I’m going to do the work, hoping it will get me to my goals. As, honestly, even writing this blog post has.

(This is future me in my castle in the forest. I have invisible gardeners, because of course I do. The illustration is by Charles Robinson.)

January 24, 2016

Keeping It Real

Recently, I was looking at another writer’s biography and noticed that he had attended all sorts of prestigious writing residencies. And I thought, wait, am I supposed to be applying for those? Maybe I should be applying for residencies and grants . . . After all, they look good on your CV. Don’t they?

I had to remind myself to keep it real.

Here’s real: What is the purpose of residencies? They give you places to write. I already have a place to write: my home office is where I write everything, and the most comfortable writing place I know. What is the purpose of grants? To give you money so you can write. But since I teach more than full-time, the chance that a grant will replace my income, much less my benefits, is very small. So what residencies and grants would really give me, right now, are . . . a line on my CV. A reference in my biography. And that’s not enough.

I have to think about what is real because at one time, I went wrong . . . I made decisions based on prestige, on how the world would evaluate me. That was when I ended up at Harvard Law School. It was my last year of college, and I wanted to go on to a PhD program, specifically to study English literature. But my family discouraged me, so I applied to law school instead. I got into Harvard, so that seemed the obvious choice . . . I mean, Harvard Law is sort of like getting the world on a platter, right? Or so many people believe. The reality is that you’re never handed the world on a platter. I spent four mostly miserable years in law school, and three mostly miserable years working as a lawyer. Don’t get me wrong — I have a great deal of respect for good lawyers. I hope I was one of them. But it wasn’t for me because what was real, the deep underlying reality of my life, was wanting to write. I had wanted to write since I was a child. Instead, I was revising corporate contracts until 2 a.m. And I was deeply in educational debt.

So I paid off my law school loans (all of them, in three years, because I knew that otherwise I would die inside — and I had paid for law school entirely by myself, so they were exorbitant). I applied to graduate school. Then, I had to face the question of what was real again because I got into Boston University as well as several universities that were more prestigious, that were Ivies. But Boston University was the only one that would both pay for my tuition and provide me with a stipend I could live on. Was it worth taking on educational debt again for an Ivy League university on my CV? I actually had to think about that for a while. But in the end I decided that no, it wasn’t worth it. What was real, in this situation, would be the education I was getting, the focus on literature, the time to write.

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve gotten better at distinguishing what is real from what is not — or perhaps what is simply less real, less important. Real are the stories I write, the books I publish. Not a prestigious residency or grant, unless it leads directly to more stories, better books. Real is money for food and shelter. Real is raising my daughter. Real is having lovely things around me.

Hunger and cold are real. Fear and failure are not — they are just the way my mind perceives reality. But they are interpretations, not facts. Joy, on the other hand, is real. (Why joy and not fear? Because I usually realize that my fear is a misinterpretation of the world, whereas my joy rarely is. Joy leads me right most of the time. Fear, rarely. Although if I were to encounter a ravenous bear, then yes, my fear would be real, and I would listen to it.) Literary prizes are real if they result in more people reading my books, or represent people I respect recognizing my work. Those are real, but the important things are the quality of my work and the extent to which I am able to reach out, speak to people through my writing. Those are the things I need to focus on.

I’ve been online long enough to realized that most internet controversies are not real. They do not change any minds, and have no tangible result in the world of actual things. Real requires substance behind the appearance (which is why fear of ravenous bears is real, when there are actual ravenous bears in the vicinity).

I hope all of this makes sense? I feel as though I’m trying to describe something rather nebulous in words, which are concrete. But what I ask myself, over and over in my life, is this:

What is real?

Because I’m tempted by the unreal as much as anyone — by prestige, by what I’m supposed to be doing. According to whom? I’m not sure, probably the invisible audience we all create in our heads of people who are judging us. Don’t you do that? Don’t you imagine an audience of people who don’t even know you, judging you for your failures? Our imaginary audiences can be harsher than any actual people . . .

So I bring myself back again and again to that question, every time someone asks me to do something or I create a new project for myself. Am I doing this because it will have some real effect, because it’s something I actually want to do? Or am I doing it because it will look good in my biography? What is real to me, what do I truly care about, what will actually change my life or perhaps myself?

I’m a fan of Mari Kondo, the Japanese neatness guru. I try to follow her injunction to only keep those things that truly give me joy. (Although I have a lot of those things — my life is definitely not minimalist.) I’ve even folded my clothes the way she suggests . . . But I think that message should be applied not only to how we organize our stuff, but also how we organize our time. What is real, what sparks joy? Some things that are real may not spark joy, certainly not all the time — if you’re working at a job you dislike because you need to pay off your educational loans, then you may not get a lot of daily joy from it. But you will at least have the satisfaction of knowing those loans are going away, month by month. (For a while, my greatest sense of joy was in looking at my diminishing loan balance.) That sense of accomplishment is real — it is a thing that exists and is important.

Sometimes I practice distinguishing what is real, because our culture makes it so difficult to tell the difference. It sells us substances that are not real food. It tells us companies are worth a billion dollars based on stock valuations that are going to change tomorrow. It praises celebrities who are famous for being famous, without actual accomplishments.

Do this: find the real, underneath. If you’re standing on that, I find, you’re standing on solid ground. You have a sense of stability, a sense that you know what’s what. When I lose that sense, when I’m not sure where I’m going and the world seems to be spinning out of control, I think, what is real right now? Lunch. Papers to grade. The fact that I have a warm jacket, so I will not be cold when I go outside, although it’s snowing. And there’s comfort and joy in that solidity.

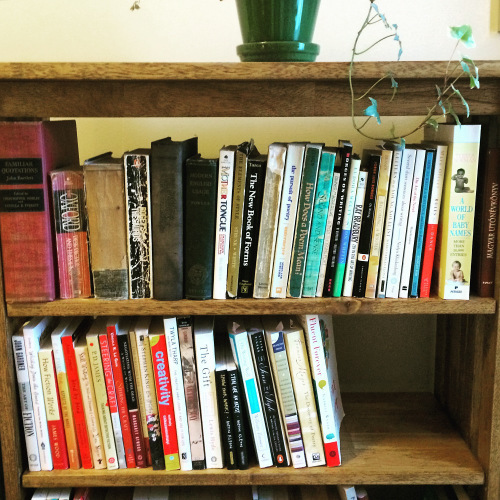

These are two pictures from my office. First, a quotation pinned to the corkboard above my desk . . .

And second, my writing books — the ones I’ve found most valuable and reread periodically.

January 17, 2016

Stasis and Stability

It feels strange to be where I am now: for the first time in, well, ever, my life feels stable. Oh, I know that could change tomorrow. I’ve gone through so much instability in my life that stability actually worries me . . . I start wondering if I’ve fallen into a period of stasis.

My childhood was marked by constant moving. Before I started third grade, I had lived in four countries and spoken three languages. After that, it was one country and one language, but the longest I ever went to a single school was three years. We just kept moving . . . Then college, then law school, then working as a lawyer for three years, then graduate school . . . I was always either moving or working towards — something else. I was never someplace I could stay. There was never a sense of home.

Now I’m in a place where I could stay, theoretically, for the next twenty years, and honestly it’s a little scary. I have a stable academic position, I teach writing in two places I love — to both undergraduates and graduate students. And I’m writing. I have a novel contract — for two novels, in fact! I have deadlines. Honestly, I’m doing more work than I’ve ever done before in my life, but it’s the work I wanted to do. And I could just keep doing it. This is what I was working towards, all those other years, the unstable ones.

So what now? Because the truth is that I don’t want to fall into stasis, to simply keep doing what I’m doing. What I want is to use this stability as a platform. First and foremost, to keep writing. I have so many ideas, so many things I want to write about. So many projects I haven’t even started tackling yet. And as I said, I have two books coming out: one in 2017 that I’m going to be editing in the next few months and one in 2018 that I still have to mostly write . . .

So I think there are several lessons for me here:

1. Most importantly, stability could change. I know this, know it deeply in my bones. I have cancer in my family, so I know perfectly well that one medical diagnosis can change everything. And I know that anyway, time’s passing. I have a limited amount of time on this earth — none of us knows how limited our time is. So I need to do what I want to get done, not with a sense of panic, but with a sense of purpose.

2. Second, stability is not stasis if you use it wisely. Stability can be where, rather than being blown about by events, you sit down, ask yourself what you want to accomplish, and then accomplish it. And that’s what I need to do . . . the accomplishing part, since I already have a list of the things I want to accomplish. It’s on my cork board, above my desk. It’s not a long list, but it includes items like my goals as a writer.

3. Third and finally, be grateful. I’ve had so little stability in my life that when it came, it felt almost frightening. I had to keep reminding myself that this was a good thing. That this was a place where I could, for the first time, be truly productive.

Once, I read an article about the Hungarian writer Imre Kertész, who won the Nobel Prize. For years, he had worked as a translator, living in a small apartment in Budapest with his wife. He talked about having chosen that life deliberately so nothing would distract him from his writing. He had chosen a life of as much stability as he could, a life that did not require him to earn a great deal of money, a life that would support him just enough so he could write. So he could bring the images in his head into being. I’ve thought about that article ever since. It’s so easy for me to get distracted — this is a very distracting world we live in. But right now, right here, I have all the things I need. A lovely, warm home. Work that supports me — a lot of work, but not so much that it takes absolutely all my time (although some weeks it feels as though it does). Time to write, if I organize my time well enough, and if I have the calm, centered focus I need to do it. That focus is learned, not something that just happens — it’s something I need to create.

So here’s the plan: I’m going to teach, because that’s my job. And I’m going to write, because that’s what I’ve wanted to do just about all my life. In the past, I fit writing in around the instability, and still got a lot done. But it’s only recently that I’ve been able to write anything long, like a novel. Before, writing was always competing with things like, you know, graduate school. And surviving . . . Now I’m not just surviving. I have food in the refrigerator, heating in my apartment, and money in my savings account. (That last one — honestly, I wasn’t sure I’d ever get there!) So it’s time for me to produce.

To be perfectly honest, I feel deep in my bones that where I am now is not where I’ll always be. But the next step, whatever it’s going to be, is something I have to create for myself. So that’s what I’m going to do.

The photographs below are from Christmas Day, when I went to a bird sanctuary and wildlife refuge in Concord, Massachusetts. It was so peaceful there. And I thought about all these issues, about how stability was a good thing. It wasn’t necessarily stasis, or stagnation. Although really if you think about it, what is stagnation? A stagnant pool is absolutely filled with life, at the microscopic level. The fact that we can’t see it doesn’t mean it’s not there. The fact that we can’t see how what we are doing now is creating our future doesn’t mean it’s not being build, deep underneath, underground in our selves and souls. What we build there during times of stasis often creates the changes in our lives.

It’s as though we are winter forests. We may see dead leaves, bare branches. But the life is all underground, just waiting.

December 26, 2015

Guilt and Shame for Writers

I’ve been thinking about this issue a lot.

Several days ago, I posted the following:

1. Guilt and shame are the enemies of the artist.

2. Guilt is when you feel as though your time should be spent doing something else, for someone else.

3. Shame is when you think what you’re producing is not good enough, or you’re not good enough as an artist.

4. The only way to deal with guilt and shame is to feel them, because you’re going to feel them. Then do, and show, the art anyway.

I have to deal with guilt and shame all the time. I think most artists do. Guilt and shame are two different things, so I’m going to try to define them. But they’re similar in that they’re equally debilitating. And equally difficult not to feel — I think they afflict most of us who are trying to do creative work.

Guilt is focused inward and has to do with a sense of what you should be doing that is not art, and who you should be doing it for. I have a daughter; time I spend writing is time I don’t spend with her. I have a sense of duty as her mother, but of course I have a lot more than that — I want to spend as much time with her as I can, because time passes quickly and I know she’s growing up. Every experience we have together, even if it involves sitting on the sofa watching a movie, is precious. And I have students, a lot of them. I have a sense of duty towards them, and also toward the university programs that employ me — but beyond that, I want them to learn and succeed. Time I spend writing is time I don’t spend grading their papers, creating lessons plans. Would I be a better mother and teacher if I didn’t write? I don’t know. I’m sure I would have more time . . .

So that’s guilt: the continual sense that you should be doing something else, for someone else. The sense that writing is an indulgence, and your duty lies elsewhere.

Shame is different: it’s a sense about the work itself, that it’s not good enough, will never be good enough — for others. Shame has to do with how other people perceive you. If you never showed your work to anyone, you would not have a sense of shame about it. You might have a sense of failure, but it would be a private failure. You would feel relief — at least no one has to see how I failed!

Shortly after I posted about guilt and shame, I also posted the following:

Everything I write is a failure in some way. It never lives up to my original idea of it.

I think that’s true for so many writers. You have the story in your head, which you’re convinced is going to be the best one you’ve every written. And by the time it gets onto the page, it’s a flawed, awkward thing, like a young falcon, wet, tousled, squawking for worms. And you think, what happened to my original perfect conception? All the words are wrong. Even the commas are wrong . . . By that point, you’re convinced it’s the worst story you’ve ever written, and your writing career, such as it was, is over.

The more you write, the more you realize that this is a cycle, that it happens every time. Months later, particularly if you see the story in print, you’ll think — it’s not that bad after all. Not perfect certainly, but not the worst I’ve ever written either. But understanding that it’s a cycle and actually getting rid of the shame are different things — understanding happens in the conscious mind, whereas the sense of shame lies much deeper, in the unconscious. Understanding simply brings it to consciousness, helps you talk to yourself about it. The shame itself doesn’t go away.

At least I’ve found this is the case for most writers. It seems to me that there are writers without that sense of shame, who are confident in their own writing (although how would I know, since I don’t inhabit their heads). They tend to be writers who were encouraged by their families and teachers from a young age. The rest of us, particularly if we were discouraged at some point, have internalized a sort of societal voice. It says both that the work is not good enough and that you, as a writer, probably as a person, are not good enough.

And then it becomes not about the work, but about you: I must not be good enough, I must not be smart and skilled and dedicated enough, to be the writer I imagine I could be.

Therefore, says guilt, you’re wasting time. You really should be doing something else: volunteering at the local food pantry, supporting a political cause you believe in. Serving on the PTA. Don’t get me wrong, those are all good activities. But guilt says, you should do them instead of your art. Because, adds shame, your art is worthless.

If this were a self-help article, this is the point at which I would tell you how to defeat guilt and shame, as though they could be removed like an appendix. It’s not that easy. I’m pretty sure guilt and shame are here to stay.

All I can tell you is what I do. The first step is understanding what they are, and how they’re stopping you. And then, since they’re different, approach them differently.

Guilt: If you have the something inside you that makes you a writer, or a painter, or a musician, it’s like an itch. I find myself writing all the time, whenever I have free time. For fun, because that’s what I enjoy doing. When I can’t write, it’s like an itch in the middle of my back that I can’t scratch. Or worse, because I start getting tangled up inside. It’s as though writing untangles me. What I believe is that if you have that particular itch, something put it in you — call it what you will, but you were created with a purpose, and it’s that purpose, unfulfilled, that causes the itch, that makes you want to scratch at it, almost desperately. You were make to create whatever you have the impulse to create, and your unhappiness when you’re not creating is it the universe itself speaking to you, saying: hey, you’re ignoring me.

So yes, you have a duty to your family, to your students. But you also have a duty to yourself, and to something greater than yourself — to the work itself that wants to be created through you, and to the creative power of the universe that is trying to find a means of expression and has chosen you for it. If you ignore that duty for all the others, you will end up unhappy, unfulfilled. If you’re anything like me, you’ll probably end up feeling guilty for a whole new reason . . . now you’ve failed in your duty in another way, to yourself and God or whatever! But at least you’ll be able to see that these are competing duties, and that sometimes your parenting or teaching need to come first, but at other times your writing needs to come first. And then, maybe, you can start to negotiate among them.

Shame: The only way I know to deal with shame is a form of behavioral therapy in which you do exactly what you’re afraid of. And if you don’t die, then you know that you probably won’t die . . . the next time you receive a rejection, or moderate a panel, or do a reading. It’s not fun, but it works. Whatever you’re afraid of the world seeing you do, do that. Every time I publish a piece of writing, I feel a sense of shame, because as I pointed out, everything I write is a failure. I think, this isn’t good enough to show the world. (It seemed so good after I finished writing it, but by the time I’ve revised it and I’m fixing commas, I realize that I can’t even punctuate properly, so what made me think I could be a writer?) That’s one of the reasons I keep writing and sending out the work — because it’s scary. And it’s partly why I write this blog, because who am I to offer advice, to tell anyone my views on life, the universe, or anything?

But many of you, in your kindness, tell me that what I write resonates: that you feel and see it too. And I’m betting that many of you, if you’re writers or artists, or maybe if you’re just human beings, will relate to what I’ve written above. Which is perhaps the final way to deal with guilt and shame, and equally applicable to both. Realize that aside from a fortunate few (and we’re not even sure of them), we all feel guilt and shame. We’re all in this together.

(I thought this would be the most appropriate picture for this particular post: it’s of me first thing in the morning, before I’ve washed my face or even brushed my hair. In exceptionally good light, but otherwise, as the universe made me, whatever idea it had in its head at the time. About to eat breakfast . . .)

December 13, 2015

The Joy of Poetry

I’ve been writing poetry for as long as I can remember.

The earliest poems of mine that I still have are from high school. That’s when I started writing seriously, on scraps of paper, whatever I had on hand, and then recopying my poems into a large green notebook. That’s also when I started submitting poems for publication in the school literary journal. I think it was junior year that I won my first poetry prize, for a poem on Icarus. It was published in the literary journal and illustrated by another student. I was so proud . . .

Why does a child start writing poetry? I think it’s natural for us to love poetry: after all, the first literature we’re introduced to is poetry, in the form of nursery rhymes. We clap our hands to poetry, jump rope to poetry. The difference between “Mary, Mary, quite contrary, how does your garden grow?” and John Keats’ “Ode to Autumn” is a difference in level of complexity, not fundamentally in kind. We love poetry naturally, and then we are taught out of that love, usually in school. I’m not sure how it happens. I think it starts with having to analyze poetry, to pick it apart for meaning and structure rather than letting it sing in our heads. It also comes from being taught, at the school level, only poetry that is somehow socially relevant: we are taught poetry with a political message because it’s easier to teach. The teacher doesn’t have to deal with the poetry-ness of it at all: it can be taught as social commentary that just happens to rhyme or have an underlying rhythm. Those of us who continue with poetry often belong to a particular sub-category of the high-school nerd, the literary magazine nerd — closely related to the theater nerd, and often found at the same parties.

I belonged to that category in high school. I was in theater, I wrote poetry. You could tell the literary magazine nerds because they tended to do things like read incredibly difficult books, books with intellectual cachet, prominently. They read Franz Kafka. They carried around James Joyce’s Ulysses. If they were female, they often swore allegiance to Sylvia Plath. The danger of belonging to this particular category is a kind of intellectual snobbery, but considering all the dangers of high school, intellectual snobbery is a fairly minor one, on the level of getting burnt by a toaster.

In college, I continued to write poetry. I continued to submit to the school (now university) literary journal, and at one point I was even on the literary journal’s editorial board. I continued to be published. But in college something changed. I started taking classes in writing poetry, and by the time I graduated from college, I was not sure if I wanted to write poetry anymore. I had been taking classes with famous poets (there were a several of them at the University of Virginia, where I went as an undergraduate), and they not only undermined my confidence in my own ability to write, but also made me question whether poetry was worthwhile. I think there were two reasons for this. First, the classes were intellectually lazy: they took place once a week, for several hours, and during those hours all we did was sit around and critique other students’ poetry. There was no rigor to the classes, no actual teaching. The teacher would lean back and let us do most of the work. Second, the teachers all emphasized the poetry that was then in fashion. This was the late 1980s, so confessional poetry still seemed fresh and innovative. That was the poetry we were supposed to be writing. It was all free verse of course, but not free verse in the way earlier 20th century poets had used it, with underlying rhythms and playful patterns. It felt loose, like one of the beanbag pillows that were popular then. And it felt insular, almost parochial (we never studied foreign poetry — it was always the American, sometimes English, poetry of the 1970s and 80s.) I could not make myself interested in it. If that was the direction poetry was heading in, I wanted out.

If I were to teach an undergraduate class in poetry, I would not start with workshopping at all. No, I would say, first we’re going to start by doing exercises. You’re going to write poetry in different forms: ballads, sonnets, villanelles. Because when Picasso was your age, he was imitating Velasquez. That’s how he eventually became Picasso. And it’s going to be bad, because you’re all going to be terrible at writing formal poetry — most people are. But it’s going to make you better poets, whether you’re writing in forms or in free verse. And we’re going to study the history of poetry, particularly in English but also in translation because you need to look beyond your own literary tradition. In this class you’re going to work . . . That’s the class I wish I’d had, a class that would have taught me about poetry in a deep way. That’s the sort of class I think would have inspired me.

I should rephrase my earlier statement: I still wanted to write poetry, but I no longer wanted to be a poet. Being a poet seemed incredibly pretentious, artificial — an extension of the intellectual snobbery that had seemed so cool in high school. By this point I was in law school, and I was still writing poems, on scraps of paper as I had when I was a teenager, then typing them into my computer and printing them out on a dot-matrix printer. I started sending them to small literary magazines, very small because I had no confidence in my own writing anymore. And my poems were accepted, as they had been when I was in high school and college. So I was still writing and publishing: what had changed was something inside me. I wrote though law school, then through being a lawyer — I have poems I still remember writing in my 42nd floor office in downtown Manhattan. Honestly, they were not particularly good poems. A few of them were good enough that I included them in my poetry collection, but most of them will remain hidden in my notebooks . . . The percentage of good to not-publishable was pretty low. Still, when I look at my own poems, even as far back as high school, I see something in them I like, a way of using words, an inventiveness. Writing all those poems made me the writer, including the prose writer, I am.

After several years of working as a lawyer, I went back to graduate school for a PhD in English literature. I continued to avoid poetry — all my graduate work was in prose fiction. But I wrote poetry in secret. I didn’t submit much, because it didn’t seem worthwhile. By this time I was attending fiction-writing workshops (Odyssey, and then Clarion), and I was starting to sell short stories. Unlike poetry, those paid — and editors reprinted them, so they continued to circulate, to get attention. Since my first fiction sale, I’ve been writing short stories regularly. Some of them have been finalist for or won awards, and of course I’ve been paid for them, sometimes well, but always something. My first novel will be coming out in 2017. Until a few weeks ago, I’d mostly given up on poetry. I realized, from looking at my notebooks, that I rarely wrote it anymore. At one time, I would write approximately a poem a week. Recently, there have been years when I wrote one or two . . . for the entire year, and then only because I was asked by an editor who wanted a poem for a specific purpose.

So what changed in the last few weeks? Nowadays I’m a teacher, teaching writing of all sorts, to both undergraduates and graduate students. Since November, I’ve been so busy with end of the semester work that I haven’t had time to write, and that’s not good. When I don’t write, I don’t feel quite myself . . . So I’ve been writing poetry, because that’s something I can do over breakfast, or in between teaching classes. I can finish a poem in a day and feel a sense of accomplishment. But I had to think about what to do with those poems. I didn’t want them to languish in notebooks. Trying to publish them in literary magazines no longer seemed worthwhile. When I sent poems to magazines, they were usually accepted. But it could take weeks to months before I heard back, and longer than that for the poem to actually be published. And I certainly didn’t write poetry for the money — the average payment for a poem is between a copy of the magazine and $20. Once the poems were published, few people read them — few people read literary magazines anyway, and poems get the least attention of all.

And yet . . . the few times I had shared poems online, people had liked them. They had reshared them, commented on them. That surprised me . . . I thought, why don’t I just continue to do that? So I started sharing poems on my blog. That had a magical and unexpected effect: I started writing more poetry. I think when you’re a creative person, you need to get whatever it is you’re creating out, so you can create more. If you keep it in, it starts getting blocked up, and then what you’re left with is stagnant water, like the pool behind a beaver’s dam. You want the creativity to flow like a stream. Once I started putting the poems out there, publishing them online, I started writing a lot more. And that felt good . . .

But I started running out of room on my blog. So I created a new blog, dedicated specifically to poetry. It’s called, quite simply, Theodora Goss: Poems. You can go take a look . . .

The poetry I write is rooted in myth and legend and fairy tale, not as a conscious choice but because those are the things that inhabit my head. They assume the world is deeply alive because that is how I approach the world. In a way, they are the clearest statements of what I believe in and care about — even more than my prose. They are deeply influence by the poets I have loved, some of them poets who are fashionable (W.B. Yeats, Anne Sexton), some of them poets who fell out of fashion long ago, or never were fashionable in the first place (Mary Coleridge, Robert Graves). I am particularly influenced by the history of women writing fantastical poetry, such as Christina Rossetti and Sylvia Townsend Warner. In their poetry I find a subtle subversiveness, and a fine feeling for the underlying magic of human existence. And that, fundamentally, is what I write about.

The blog is an experiment — we’ll see if it works. But my goal is simply to write more poetry and share it. If it does that, it will have fulfilled its purpose.

(The painting is by Edward Robert Hughes.)

December 12, 2015

The Bear’s Daughter

The Bear’s Daughter

by Theodora Goss

She dreams of the south. Wandering through the silent castle,

where snow has covered the parapets and the windows

are covered with frost, like panes of isinglass,

she dreams of pomegranates and olive trees.

But to be the bear’s daughter is to be a daughter, as well,

of the north. To have forgotten a time before

the tips of her fingers were blue, before her veins

were blue like rivers flowing through fields of ice.

To have forgotten a time before her boots

were elk-leather lined with ermine.

Somewhere in the silent castle, her mother is sleeping

in the bear’s embrace, and breathing pomegranates

into his fur. She is a daughter of the south,

with hair like honey and skin like orange-flowers.

She is a nightingale’s song in the olive groves.

And her daughter, wandering through the empty garden,

where the branches of yew trees rubbing against each other

sound like broken violins,

dreams of the south while a cold wind sways the privet,

takes off her gloves, which are lined with ermine, and places

her hands on the rim of the fountain, in which the sun

has scattered its colors, like roses trapped in ice.

(This poem was originally published in The Journal of Mythic Arts. It was reprinted in my poetry collection Songs for Ophelia The illustration is by the Russian artist Boris Olshansky.)

December 11, 2015

How to Make It Snow

How to Make It Snow

by Theodora Goss

First you must fall down the well.

At the bottom of the well

is the country at the bottom of the well.

That is its name, the only one it has.

You have two names, either the beautiful girl

or the kind girl, depending

on what day it is.

At the bottom of the well is a green meadow,

just like in the country you came from

but different. For one thing, the cows can speak.

They say, “Scratch our backs, scratch us

under the chin,” and you do.

The meadow is filled with poppies

and cornflowers. The air is warm,

and the sun is shining.

“Thank you, beautiful girl,” say the cows

and you walk on.

Across the meadow, there is a narrow path

worn by cow hooves. Follow it.

First you come to the oven.

“Take me out, take me out,” cries the bread.

“I’m burning up!” You take it out,

a brown wholemeal loaf. Carry it with you

for the birds — they appear later.

Next you come to the apple tree.

“Shake us down, shake us down,” cry the apples.

“We’re ripe!” So you shake the branches, as though

you were dancing with them.

The apples come tumbling down.

You put three in your pocket.

Now you are at the edge of the forest

and the birds call, “Feed us, feed us!”

You ask the loaf, “May I?”

“This is what I was baked for,” says the loaf.

So you scatter breadcrumbs

and the birds come, sparrows and chickadees,

robins and finches and juncos,

and a nuthatch. They perch on your arms

as you feed them. Absentmindedly,

you whistle as they do.

In the forest, a wild sow approaches.

For the first time you are afraid and step back,

but she says, “My little ones are hungry,

and I smell something sweet.”

You pull the apples out of your pocket.

“May I?” you ask, and the apples reply,

“This is why we fell.”

You kneel while the sow watches protectively,

feeding the apples to her three piglets,

bristle-backed, with tusks just starting to form

but still striped as though someone had marked them

with her fingers. The sow nods and says,

“You are a kind girl.” Then, followed by her progeny,

she disappears into the trees.

You continue alone.

It is getting dark. You have passed through the oaks

and now it is all pines. You are walking on needles.

The light is fading when you come to the cottage.

It looks like the cottage out of a fairy tale:

peaked roof like a witch’s hat, dark green trim,

small-paned windows through which firelight is flickering.

Someone is waiting for you.

You have nothing left, no bread, no apples.

So you knock.

The woman who answers is old, small,

like a doll made of cornhusks.

“You’re hungry,” she says,

“and tired. Come in, my dear.

The soup is almost ready.”

There is a fire, and a cauldron on the fire,

and a chair by the fire, and a cat in the chair,

and you can smell the soup.

“Come on, then,” says the cat, and gets up,

but only to settle again in your lap

once you sit down.

Here are the things you know about the old woman:

she milks the cows, she causes the apples to ripen,

she teaches the birds their songs, she runs her fingers

along the backs of the wild piglets

to put the stripes on them.

Here are the things she knows about you:

everything, also your name.

“What are you called, my dear?” she asks.

“The beautiful girl,” you answer. “Or the kind girl.”

“No,” she says. “From now on, you shall be

she who makes it snow.

Or Holle, for short.”

Holle: it suits you.

“Here’s what I’d like you to do tomorrow morning.

Sweep the floor and dust the shelves,

wash the curtains and wind the clock,

polish the silver. And when that’s done,

shake out my bedspread until the feathers

fly like snowflakes. It’s time for winter.

Can you do that?”

You nod. Yes, of course.

That night you sleep under the cat,

in her attic bedroom.

The next morning, you put on an apron she left for you,

then sweep the floor and dust the shelves,

wash the curtains in a metal basin,

wind the clock and polish the silver. Finally,

you stand on the cottage steps under tall pines

and shake out the old woman’s bedspread.

Snow falls and falls, until

the forest is silent.

“Well done, my dear.” She’s wearing a gray wool coat

and carrying a battered suitcase. “Can you do that again

tomorrow morning, and the day after tomorrow?

I need to visit my sisters, and I’m not sure

when I’ll be back yet.

It takes a responsible girl, but I’ve heard good things

about you from the cows, the bread, the apples,

the birds, even the trees. And the cat likes you.”

“I’ll do my best,” you say.

She kisses you on both cheeks, then rises up, up,

through the trees until she is only a speck

in the colorless sky.

You go back into the cottage.

There is a cat to scratch under the chin,

and books with stories you have never read,

and you haven’t introduced yourself to the clock yet.

Besides, you like your new name.

It’s the right name for a woman

who makes the snow fall.

(If you know fairy tales, you’ll recognize this poem as a sort of prequel to the Grimms’ “Frau Holle.” I could not find a source for the illustration, but I’m guessing it’s from an early 20th century edition of Nursery and Household Tales.)

Lady Winter

Lady Winter

by Theodora Goss

My soul said, let us visit Lady Winter.

Why? I responded. Look, the leaves still lie

yellow and red and orange in the gutters.

The geese float on the river. On the sidewalks,

puddles continue to reflect the sky.

My soul said, the branches are bare.

And you can feel it, can’t you, in your bones?

The chill that is a promise of her coming.

The year is growing older. Anyway,

you haven’t seen her in so long: it’s time.

We put on our visiting hats.

I stood admiring myself in the mirror

while my soul stood beside me looking pensive

and pale. Was she a little sick? I wondered.

Lady Winter lives on an ancient street

lined with elms that canker has not touched,

in a tall brownstone with lace curtain panels,

empty window boxes, two stone lions.

We rang the bell and heard it echoing.

A maid opened the door. Her name is Frost.

My lady looked the way she always does:

white hair, a string of pearls, rings on her fingers,

age somewhere between forty and four thousand,

a kind, implacable smile.

She said, my dear, what’s wrong? You don’t look well.

What, me? I’m fine. Perfectly fine, I said.

My soul just shook her head.

My lady has a parlor with a fireplace

in which I’ve never seen a fire. Instead,

it’s filled with decorative branches. Doilies

lie like snowflakes on the tables, bookshelves,

over the backs of armchairs.

She’s always wearing a gray cashmere sweater

and expensive shoes. She must have a closetful.

She usually serves us tea and ladyfingers.

But this time she said, I want you to go to bed.

Frost will take you upstairs, then I’ll come up

to cover you in blankets of felted wool,

comforters stuffed with down from eiderducks

that nest by Norwegian fjords. I’ll read you books

of fairytales about bears and princesses,

and stolen crowns, and castles beneath the sea,

and northern lights.

Grandmothers who grant wishes, talking reindeer,

a village in the clouds.

I’ll talk to you until you fall asleep.

Your soul will sit and watch through the long night.

From time to time she’ll take your temperature

to make sure you’re all right.

So I lay down in Lady Winter’s guest room:

reluctantly, but it looked so inviting,

a bed with draperies and a painted ceiling

from which the moon was hanging

by a silver chain.

My soul sat down beside me.

Don’t worry, she said. There’s plenty for me to do.

Poetry to embroider, plans to knit.

I’ll wake you when the crocuses have broken

through the black soil, when warmth has come again.

Then Lady Winter put her soft, dry hand

like paper on my forehead

and she said

rest now.

(The image is by Elizabeth Sonrel.)

Snow White Learns Witchcraft

Snow White Learns Witchcraft

by Theodora Goss

One day she looked into her mother’s mirror.

The face looking back was unavoidably old,

with wrinkles around the eyes and mouth. I’ve smiled

a lot, she thought. Laughed less, and cried a little.

A decent life, considered altogether.

She’d never asked it the fatal question that leads

to a murderous heart and red-hot iron shoes.

But now, being curious, when it scarcely mattered,

she recited Mirror, mirror, and asked the question:

Who is the fairest? Would it be her daughter?

No, the mirror told her. Some peasant girl

in a mountain village she’d never even heard of.

Well, let her be fairest. It wasn’t so wonderful

being fairest. Sure, you got to marry the prince,

at least if you were royal, or become his mistress

if you weren’t, because princes don’t marry commoners,

whatever the stories tell you. It meant your mother,

whose skin was soft and smelled of parma violets,

who watched your father with a jealous eye,

might try to eat your heart, metaphorically —

or not. It meant the huntsman sent to kill you

would try to grab and kiss you before you ran

into the darkness of the sheltering forest.

How comfortable it was to live with dwarves

who didn’t find her particularly attractive.

Seven brothers to whom she was just a child, and then,

once she grew tall, an ungainly adolescent,

unlike the shy, delicate dwarf women

who lived deep in the forest. She was constantly tripping

over the child-sized furniture they carved

with patterns of hearts and flowers on winter evenings.

She remembers when the peddlar woman came

to her door with laces, a comb, and then an apple.

How pretty you are, my dear, the peddlar told her.

It was the first time anyone had said

that she was pretty since she left the castle.

She didn’t recognize her. And if she had?

Mother? She would have said. Mother, is that you?

How would her mother have answered? Sometimes she wishes

the prince had left her sleeping in the coffin.

He claimed he woke her up with true love’s kiss.

The dwarves said actually his footman tripped

and jogged the apple out. She prefers that version.

It feels less burdensome, less like she owes him.

Because she never forgave him for the shoes,

red-hot iron, and her mother dancing in them,

the smell of burning flesh. She still has nightmares.

It wasn’t supposed to be fatal, he insisted.

Just teach her a lesson. Give her blisters or boils,

make her repent her actions. No one dies

from dancing in iron shoes. She must have had

some sort of heart condition. And after all,

the woman did try to kill you. She didn’t answer.

And so she inherited her mother’s mirror,

but never consulted it, knowing too well

the price of coveting beauty. She watched her daughter

grow up, made sure the girl could run and fight,

because princesses need protecting, and sometimes princes

are worse than useless. When her husband died,

she went into mourning, secretly relieved

that it was over: a woman’s useful life,

nurturing, procreative. Now, she thinks,

I’ll go to the house by the seashore where in summer

we would take the children (really a small castle),

with maybe one servant. There, I will grow old,

wrinkled and whiskered. My hair as white as snow,

my lips thin and bloodless, my skin mottled.

I’ll walk along the shore collecting shells,

read all the books I’ve never had the time for,

and study witchcraft. What should women do

when they grow old and useless? Become witches.

It’s the only role you get to write yourself.

I’ll learn the words to spells out of old books,

grow poisonous herbs and practice curdling milk,

cast evil eyes. I’ll summon a familiar:

black cat or toad. I’ll tell my grandchildren

fairy tales in which princesses slay dragons

or wicked fairies live happily ever after.

I’ll talk to birds, and they’ll talk back to me.

Or snakes — the snakes might be more interesting.

This is the way the story ends, she thinks.

It ends. And then you get to write your own story.

This image is The Enchanted Wood by Helen Jacobs.