Theodora Goss's Blog, page 74

December 24, 2010

The Longest Night

I was going to write a post on the night of the Winter Solstice with this title, but that night I was still grading papers, and I did not have the – focus, I think. I'm still not sure I have it now.

What I want to write about is two thoughts I've had lately, one about darkness, one about writing.

Here is the first thought.

I think that when the caterpillar is spinning its cocoon, it thinks it's dying. It's going into the darkness, into a claustrophobic darkness in which it will transform, but how do we know that it, the caterpillar itself, knows that? I think it doesn't, that it goes into the darkness not knowing. And it's scared. Because it's always scary to go into the darkness, particularly the way the caterpillar goes into it: alone.

So it thinks, I'm dying. This is what dying feels like. Nevertheless, it spins its cocoon because every cell of that caterpillar is programmed to spin that cocoon, and it knows in the depths of its being, in whatever constitutes the depths of being for a caterpillar, that to spin that cocoon is its destiny, and it can't be avoided. So it spins.

Yes, this is a metaphor. Of course it's a metaphor. Aren't caterpillars and butterflies always metaphors, except when we pick the caterpillar off our roses or try to attract the butterfly with bottles of nectar? Which, if you think about it, doesn't make much sense. We want the butterfly without the caterpillar.

But the caterpillar is the longest life stage for most butterflies. They spend most of their lives as caterpillars. (If you want butterflies, you have to accept caterpillars on the roses. That's a fairly simple metaphor.) The caterpillar lives an ordinary life, the life most of us live most of the time. It eats, it grows, sometimes it becomes food for birds. (If you don't think we're all going to become food for birds, you're kidding yourself. That's another metaphor, still fairly simple.) The butterfly lives an extraordinary life. It flies, sometimes for thousands of miles, it reproduces. That really is the purpose of a butterfly: it is the reproductive form of the caterpillar.

This is another metaphor, the third and last, and I think the most complicated. There's a reason the butterfly has often been used as a symbol for the soul. It is that in us which reproduces, but I don't mean physically. I mean mentally, spiritually. The butterfly is a metaphor for that in us which produces art. It is the artist. (I know, you could see that one coming.) I identify production with reproduction because what the artist produces is always drawn out of the self. It is an image of the self that is nevertheless different from the self, as the egg is different from the butterfly.

So the caterpillar going into the darkness, drawing filaments out of itself, wrapping them around itself, does not know what it's doing. It does what its instincts tell it to do. And when it goes into the darkness, it thinks, this is what dying feels like. And it does die, because transformation is a kind of death. The caterpillar that was is no longer going to exist. What comes out is the butterfly, which we think is so beautiful, which we watch through our binoculars as it flies thousands of miles to Mexico or Brazil, telling each other how lovely, look at them!

And we do not think about the darkness that butterfly came out of. How it, on its journey, thinks: I died. I am born again. And with the sun on its wings, it almost, but not quite, forgets the pain and terror of death.

Here is the second thought.

There are two types of writers. (This statement is as simplistic as any statement that attempts to systematize the world. Bear with me.)

The first type, I will call the School of Eliot. These are writers who write about what happens in the world, about the human beings in it, what they do, how they think. Middlemarch is the epitomic (yes, I made up that word) School of Eliot novel. I walked though a bookstore today, and most of the books I saw were of that school. They were about human beings living their lives, loving, failing to love, becoming sick or well. Struggling to understand parents or children. Traveling to India for enlightenment. That sort of thing.

The second type, I will call the School of Kafka. These are writers who write about something different, not what happens in the world but that world itself as it is constituted, its structure. Not about a human being attempting to become a better mother, daughter, proprietor of a cupcake shop. About what it means to be a human being in the first place, how we define the human, how we define being. It's as though, rather than writing about the physical world, they are writing metaphysics.

I think you can see this distinction even in genre fiction. For example, Edgar Rice Burroughs belongs to the School of Eliot. He is concerned entirely with the physical world. Tertius Lydgate struggling to establish a medical practice that allows him to do research, John Carter struggling to defeat the Tharks so he can rescue Dejah Thoris. It's all about how to live in the world as it is, as a given. On the other hand, H.P. Lovecraft belongs to the School of Kafka. Gregor Samsa lives in a Lovecraftian universe that operates by rules he does not understand. The novel asks us to consider, what are the rules of the world anyway?

As I said, this is of course an oversimplification, but it is what I was thinking today, walking through the bookstore. And I was thinking that there were many more writers of the School of Eliot than of the School of Kafka. One would think the School of Eliot would be more comforting. After all, it tells us that the world we live in is real, a given, something that should not be questioned. We don't need to worry about turning into an insect or being destroyed by an Elder God. (Unless, that is, the novel explicitly tells us those things are possible, but then there are usually ways to avoid or counteract such fates.)

But when I've done into the darkness, and I've thought, maybe this is what death feels like, I've always chosen the School of Kafka to comfort me. Today I came home with Italo Calvino's Invisible Cities, Difficult Loves, and Mr. Palomar. That is not a metaphor, and therefore I have no idea what it means.

December 23, 2010

Thinking about Lovecraft

First, I want you to go look at this video: Fishmen.

Did you get it? You did if you've read H.P. Lovecraft's "The Shadow over Innsmouth." It's all about the fishmen who inhabit that city, and the narrator does, at the end of the story, discover that his ancestry is Innsmouthian, and fishmenian as well. He feels himself start to transform.

If you go to YouTube, you will find many videos based on Lovecraftian themes, some of them set to Christmas music. I've seen a number of them around. People start posting them to Facebook, and the like.

So my question of the day is, why Lovecraft? There's something about him, about the whole Cthulhu mythos or non-mythos, that seems to have captured our imagination. People crochet Cthulhu dolls. People cut Chulhu-shaped paper snowflakes. People make Cthulhu gingerbread cookies. (At least, they did tonight at my house.) And the time for Lovecraft seems now. There are Lovecraft-themed anthologies. It's even been said that Guillermo Del Toro is bringing At the Mountains of Madness to the movie screen.

I don't think anyone paid much attention to Dracula when it first came out. But something about it started to capture the popular imagination. It was the Count himself, the Eastern European aristocrat who was also a blood-sucking vampire. The potential romantic partner who also wanted to suck your blood. (Although the Count wasn't exactly Tom Cruise or Brad Pitt in the novel.)

But there was something about Count Dracula that resonated, as there is something about Lovecraft's universe that resonates with us. I think it's that as we've gone through the twentieth century, Lovecraft's universe has, more and more, turned out to be the place we actually inhabit. It's common for critics to say that Lovecraft belongs in the nineteenth century, that he is in a sense a late nineteenth-century writer. That may be true stylistically. But in terms of his ideas about how the world we live in operates, he belongs right where he was born, around the same time as Franz Kafka. He tells us that our world operates by laws we do not understand. That the universe is larger than we know, and older, and that it does not care about us. He tells us that we can lose our humanity more easily than we imagine. Here I think he really is like Franz Kafka.

But there is also something in Lovecraft that belongs to a later time, and this is why I think he resonates with us. There is something fundamentally postmodern about what he's doing, because whereas most of the late nineteenth-century writers were deeply disturbed by the transformation of something human into something not human, by the abhuman, Lovecraft glories in it. Oh, his narrators tell us how terrible it is, how frightening. But I think Lovecraft is having fun.

And every once in while he tells us that the abhuman, the monster that was once human but is no longer, is having fun as well. At the end of "The Shadow Over Innsmouth," the narrator glories in his connection with the fishmen, wants to break out of his mental asylum and go down into the waters off Innsmouth, down to the city of his ancestors. At the end of "The Outsider," the narrator who discovers that he has been dead, probably for centuries, when he looks into a mirror realizes that he is a monster and goes to live with the other monsters. He tells us,

Now I ride with the mocking and friendly ghouls on the night-wind, and play by day amongst the catacombs of Nephren-Ka in the sealed and unknown valley of Hadoth by the Nile. I know that light is not for me, save that of the moon over the rock tombs of Neb, nor any gayety save the unnamed feasts of Nitokris beneath the Great Pyramid; yet in my new wildness and freedom I almost welcome the bitterness of alienage.

What the narrator implies is that it's painful to be a monster, it involves loss. But it's also way cooler. It involves riding with ghouls and playing among the catacombs, attending those unnamed feasts of Nitokris, all things to which we as ordinary people have no access. Monsters are cooler than we are.

I think that's why I love Lovecraft, despite all his faults (and he has many). Almost despite himself, he's on the side of the monsters.

December 22, 2010

Writers and Copyeditors

So, I wrote a story called "Fair Ladies." It was published in Apex Magazine, and then Jonathan Strahan asked to reprint it in The Best Science Fiction and Fantasy of the Year, Volume Five.

I received the copyedits, and I could immediately see that they were terrific. When you're a writer, there's nothing you care about more than having a good cover and a good copyeditor. The copyeditor, in particular, saves your life. There was one suggested change that amused me: I had used the "kroner" as the currency of Sylvania, where the story is set, and the copyeditor informed me that kroner was plural, and the singular would be krone. He was right of course. What was amusing, to me, was that I hadn't even thought about the fact that a krone, or krona, depending on which country you're in, is an actual unit of currency. In my mind, I had just seen the Sylvanian kroner, with the head of King Radomir IV on it. Of course, it had come into my head because there was a krone, a krona: because there were currencies out there named after the Latin for crown, corona. If that hadn't been floating out there, I would never have thought of "kroner." I wanted my currency to sound vaguely but not exactly like any other European currency. But in Sylvania, the kroner is singular. Nowadays, you can buy coffee with about ten kroners. (Or about five Euros.)

I mentioned all this on facebook, and Marty Halpern, who turned out to be the copyeditor, wrote me a comment about it. And then we exchanged some comments, me and Marty and Paul Witcover, who joined in, about the writer brain and the copyeditor brain, how they were alike and different. Marty asked if he could reproduce and comment on that conversation on his blog, and the two of us said that of course he could, so here it is, on writers and copyeditors: Writing with Style (Sheets, That Is).

It's a fascinating account of how copyeditors think and why writers should produce style sheets. One comment of Marty's particularly intrigues me:

"Dora states that the comments provide insight into the mind of a copyeditor, but I feel that Dora's explanation of how she came to use 'kroner' provides some wonderful insight into the mind of a writer, which is far more complicated than that of a copyeditor, trust me on this – we follow the rules; writers break the rules and create their own!"

Is this true? And I guess at some level I'm asking not just whether writers think differently from copyeditors, but whether they think differently from other people. And I suppose I'm thinking not just of writers, but of artists of all sorts. They break the rules and create their own. That's what they're supposed to do.

What that reminds me of is a quotation from Albert Camus that I saw somewhere: "Nobody realizes that some people expend tremendous energy merely to be normal." Is that really from Camus, or one of those things people say Camus said? I hope it is from him. Because I think it's deeply and absolutely true. "Some people," in that quotation, could refer to writers, because they do break the rules and create their own, and if you have a brain that's constantly creating its own worlds, sometimes it's difficult to see, and you have to force yourself to see, that the physical world outside your own brain still exists. It's almost as though – wait, you see, a story is coming to me. About a writer who keeps on losing the world, the actual physical world outside his head, and so he needs to keep writing things down, because that's the only way he can capture it. He keeps writing down the rules.

Fire burns.

Don't cross against the light.

You must pay for things. You may not simply take them.

Say hello, remember to shake hands, when you leave say goodbye.

If in doubt, nod.

No smoking.

You see? He has to write down the rules because otherwise he won't remember them, otherwise he will believe that the world inside his head, which is a different world altogether, is the real world.

Oh copyeditors! How do you do it? Do you really think differently than I do? (And does it have anything to do with something I just realized, that the tone and format of Marty's post is completely different from mine? I started with style sheets and ended up with an existential yawp.)

Thank goodness for copyeditors, and editors of all sorts in general, because what would this world be like with only writers in it?

No one does existential yawps better than Camus, so let him have the last word, on this day after the shortest night:

"O light! This is the cry of all the characters of ancient drama brought face to face with their fate. This last resort was ours, too, and I knew it now. In the middle of winter I at last discovered that there was in me an invincible summer."

December 21, 2010

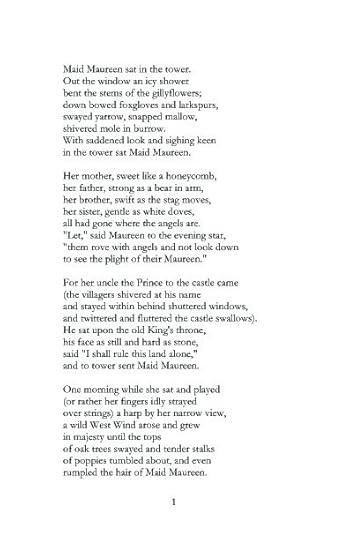

Maid Maureen

So today I went to see the friendly copy shop people, and they told me that it would be easy for them to make a booklet for me. I wouldn't even have to do the layout or printing myself, I could just bring in a file and they would print that file for me, arranging all the booklet features. (Like, you know, how all the pagination works, and all that.) And we went through all the costs, for paper, printing, binding, folding, cropping if necessary, etc.

And so I came home and started to make another booklet, formatted differently this time. I took a poem I had written a long, long time ago, a poem called "Maid Maureen." It's a sort of parody of an old ballad, and it's about how the West Wind falls in love with Maid Maureen, trapped in her tower. I used a John William Waterhouse painting that I believe is called Boreas for the cover image. Here's what the cover looks like, but you can't quite tell the size because it doesn't have a border. That's because I learned how to save the document as a PDF, then open it in Photoshop and save it as a JPG. Rather than copying and pasting, which is what I did last time. I think I'm getting pretty good at this.

And here are two pages:

I'm really rather proud of myself. You see, my brother is Myk Melez of Mozilla (google him, he gets more hits than I do). He's, like, a computer whisperer. And I really don't have an intuitive sense for technology, at all. But I like to know how to do things like create websites and publish small books myself, because those are the sorts of skills that come in handy when you're a writer.

I don't know, maybe I'll actually make "Maid Maureen" into a booklet and then do – what with it? Let me know if you have any ideas.

And here, in case you're interested, is Boreas, which I think is a gorgeous painting:

December 20, 2010

Guilty Pleasures

I'm talking about literary guilty pleasures of course, although I have discussed my addiction (seldom indulged except on airplane flights) to chocolate-covered pretzels on various occasions.

One of my guilty pleasures is Agatha Christie murder mysteries. In a strange way, it's like my pleasure in poetry. It's the pleasure of pure form. I want to see the form of the murder mystery play out, I want to see her variations on it (because she would rewrite the exact same mystery as a novel and a short story, altering the motive and victim). I don't care whether I've read that particular mystery ten times and know who the murderer is. I don't care that her protagonists are all going to behave as they should, the countess being a true countess, the butler a true butler. I just like reading them.

Another guilty pleasure, and the one I really wanted to talk about, is the occasional Oprah Magazine. There's something fascinating about its combination of uplifting articles, fairly aggressive financial and relationship advice, and expensive advertising. I'm supposed to accept myself as I am, save a financial cushion equal to six months of my salary, and buy $200 dresses. It's enough to make me dizzy with the contradictions of late capitalism.

But what I sometimes get out of the magazine are valuable bits and pieces of – what shall I call them? Magical thinking? Like the following, in the "What I Know for Sure" section of the January 2011 issue:

"Fear comes from uncertainty. Once you clarify your purpose for doing something, the way to do it becomes clear."

That is magical thinking, isn't it? Once you know why you want to do something, you can still flounder in the morass of figuring out how. But for the most part I think it's actually true, and magical thinking is like that. It usually has an underlying veracity and effectiveness to it. (I didn't say I don't believe in magic.)

I do think that fear comes from uncertainty. If you're not sure what you want to do, or why, you're going to be fearful, you're going to hesitate. You're going to make the wrong decisions, and then try to figure out why you made them. And once you clarify your purpose for doing something, it's not necessarily that the way to do it becomes clear to you, consciously. But things start getting out of the way. It's as though you suddenly think, but that's not going to help me get where I want to go. It's a great opportunity, but it's not my opportunity. It doesn't contribute to the ultimate goal I've set for myself. And that does help. That does make the process easier.

These particular sentences struck me because they made me ask myself, do I know why I want a writing career? I don't just want to write. Anyone with a pen and paper can write. Nowadays, anyone with a computer can publish. I want a writing career, which means that I want to write, and be asked to write, and teach writing. I want to be part of the dialog about writing in my time, and perhaps if I'm very lucky after my time. I want to be part of the world of literature.

Why?

I think the answer is that I look at the world around me, and it's not the world I want to see. It's filled with things I don't think it should be filled with: ignorance, cruelty, sordidness. And I believe, on a deep and fundamental level, that we can only change material conditions by changing ideas. That's why we need to tell stories, that's why art exists in the first place. It allows us to see things that we can't see in any other way. So I want to – not make people see things differently, because you can't make readers do anything, but offer them another way of looking.

That sounds awfully ambitious, doesn't it? But another thing I've learned from Oprah Magazine is that you need to admit to your ambitions. If you don't, if you pretend that all you want to do is – it doesn't really matter what I'm going to write, the operative word is "all" – "all" you want to do is whatever, then it's as though you're starting by tying one hand (probably your writing hand) behind your back. If you start off admitting that what you really want to do is change the world, because it doesn't seem to you at all satisfactory in its current state – that does at least give you a sort of freedom. (And a sort of permission to fail, because you're going to fail, of course. You're never going to change the world. But you might change a perspective or two or three.)

I'm trying to work all this out as I write, why those particular sentences spoke to me, what I'm getting out of them. I think they gave me a sense of freedom. Once I clarify my purpose, and I think I'm starting to get a clearer sense of my purpose already, then the way to do what I want will become clearer as well. It will still be an enormous amount of work. But I will at least know the way to go, which is something I haven't been certain about for a long time.

(Shall I tell you the bit of wisdom I've always remembered from Agatha Christie murder mysteries? At one point, Hercule Poirot guesses that a suspect is concealing her identity based on her shoes. He tells Hastings something like this: A lady is always careful about her shoes. However cheaply she may be dressed, she will choose her shoes for their quality. I've always remembered that, and tried to choose shoes that are of good quality, that will last and can be repaired. Seriously, that's where I got it, from Agatha Christie. I have no words of wisdom to pass on from chocolate-covered pretzels.)

December 19, 2010

Making a Booklet

So I was talking to a friend today about readings, and I said to him, you know what I like to do? I like to read part of a story and then pass out copies of a booklet with the whole story in it. That way, the audience members can read the whole story, and if they want you to sign something, they have something for you to sign right there. And it's fun to have something that they're not going to get anywhere other than at that reading, something they can't buy. Something the writer made.

He liked the idea and asked me how I created booklets, and honestly, I could barely remember. It's been a while. So just to try to remember, I made one out of my story "The Mad Scientist's Daughter," which you can read on the Strange Horizons website. It took me a long time to remember how. But here's what it finally looked like:

This is just three pages, to give you an idea. (Why are the page numbers on the insides? Because when I actually print the booklet, they will be on the outsides. You tell the program to print a booklet, and somehow it rearranges everything during the printing process.)

Here's the problem. I can do something like this in my favorite word processing program, which is (don't laugh) WordPerfect 11. I think it's the most perfect word processing program ever created. Simple, clear, clean. Sort of like a typewriter with word processing capabilities. I have a deep and abiding hatred for MS Word, which I find frustratingly clunky to use.

But it takes me a while to format and print a booklet like this one. What I would really like is a program that would let me create a booklet simply, easily. As easily as I created this website on WordPress. If you know of one, will you tell me? I don't need all sorts of advanced publishing capabilities. I just want to be able to make a booklet for readings.

So I was telling my friend, who is of course a fellow writer, to think about the psychology of a reading. What can you do that will make your reading stand out, that will make people want to come and then remember it afterward? I used to do two things. First, I used to let everyone know that at my reading, there would be chocolate. (And of course there was.) And then, I used to give away booklets, as I've described. I think I'll do that again this year at Readercon, which is one of my favorite conventions. (I just received the invitation, and I will most definitely be there.) Those two things gave people something to do at the reading in addition to just listening, and then something to take away.

So I'm glad I remembered how to make booklets. Now the question is, how do I do it more easily?

December 18, 2010

The Hotel Under the Sand

"So awful things happen sometimes, but good things can happen too. The trick is to be as brave as you can through the terrible parts so you can get to the wonderful ones, because they will come along someday," said Masterman.

"That's true," said Emma, looking around at the Grand Wenlocke.

"And when they come, you have to remember how to be happy again," Masterman added. "That's very important."

"But you can't ever forget the people you lose, can you?" said Emma.

"Of course not," said Masterman. He picked up his water glass and held it up. "Here's to making them proud of us!"

Those lines are from The Hotel Under the Sand, by Kage Baker. I finished it today, and I think it's one of the best books I've read recently. Why do I like it so much? Partly because it's a strange and beautiful story, and partly because of the writing. It's deceptively simple, but also lyrical. It gives off a beautiful tone, like a glass bell. It's my favorite kind of writing, straightforward and clear, with a certain lucidity, delicacy, humor. And the story itself is wise.

I'd read two of Kage Baker's stories before, and I have to admit that I'd thought of them as relatively ordinary science fiction stories, although better than most. I picked up this book at the World Fantasy Convention, partly because I liked the title and the cover image of a pair of feet in the sand. Here it is:

And I probably opened the book and read the first few paragraphs, because I tend to do that. It begins,

Cleverness and bravery are absolutely necessary for good adventures.

Emma was a little girl both clever and brave, and destined – so you might think – to do well in any adventure that came her way. But the first adventure Emma had was dreadful.

One day a storm came and swept everything away that Emma had, and everything that Emma knew. When it had done all that, it swept away Emma too.

Isn't that a wonderful way to begin a book? It's certainly a way that will engage me at once, because I want to know what happens to little girls who lose everything, even themselves. I don't want to tell you too much about it, but it's the perfect book to buy for yourself, or for anyone you care about. The perfect present. If you're interested, you can order it from Tachyon Publications or Amazon.

In my last post, I talked about learning from other writers, and this is an excellent example. From The Hotel Under the Sand I learn that one can still write like this, in a style that reminds me just a little of E.B. White, but more fantastical. And I learn how: I look at the sentences and ask, how are they constructed, how does Baker achieve that ease, that effortlessness? And I see where the story places itself, in that liminal space I talk about, where Edward Gorey was working. (The Hotel Under the Sand reminds me just a little of Edward Gorey with sunlight. With a happy ending.) And it makes me ask, what in a story gives us pleasure? And helps me to see what does.

Like most well-brought-up children, she had always wanted to shoot off a real cannon.

Isn't that a wonderful line?

Engaging the World

If you're interested, my blog post "Why Go to the Museum?" was recently reposted on the SFWA blog. If you missed it the first time, feel free to go over and take a look!

Having my post reposted made me think about the importance, for a writer, of being engaged with the writing world – the world of other writers.

We don't necessarily think of writers as engaged, do we? We think of Marcel Proust in his cork-lined room, the solitary genius sequestered from the world. We don't necessarily think of writing as a collaborative activity. And yet – I think of the fact that Proust translated the works of John Ruskin into French. There's a way in which, if you're a writer, you have to be engaged with the world of other writers, whether past or present – and so much the better if both. You have to allow yourself to be influenced, to feel the words of other writers, their ideas, their style, affecting you, forcing you to think about what you're doing. That's not going to the museum – that is, in a sense, going to the library, even if it's just your own personal library.

But I, personally, need more than that as well. I need to spend time with other writers, sit down with them, talk to them, find out what they're doing. I need to hear about their projects and their lives, exchange manuscripts with them. That's what I get from being on facebook, reading writers' blogs, going to conventions. And from maintaining personal relationships, even if it means I'm emailing friends I only see once a year. It's also what I get from being a member of SFWA. (My dues are due at the end of this month. Note to self: pay SFWA dues!)

Because writing is, almost always, a collaborative activity. When I wrote "Miss Emily Gray," I collaborated with Henry James. When I wrote "Pug," which is coming out in Asimov's Science Fiction, I collaborated with Jane Austen. We are all writing mash-ups, all the time. Most of them are just more subtle than Pride and Prejudice and Zombies.

But talking to other writers, reading what other writers are working on this year, in this century of ours, gives me a sense of my own possibilities. There's a piece of advice writers are often given, which is to pay no attention to how your contemporaries are doing. That will just, we are told, create discontent. But I do pay attention, and I pay attention specifically to writers who are doing things I'm not, at least not yet. I'm thinking of writers like Nnedi Okorafor, Catherynne Valente, and Chris Barzak. Nnedi and I went to Clarion together, and over the years I've seen her publish short stories, then novels – amazing, inventive novels that address important social issues, even though they are also rousing adventure stories. I met Cat years ago in an airport, while we were both headed to Wiscon. I've seen her create a world for herself, a fascinating world in which she writes poetic novels that are unlike anyone else's, puts on fabulous shows with S.J. Tucker, and wears the most fantastic clothing. I met Chris at Clarion, although he had already graduated; he was just back to visit. I read a story of his back then, and it's been fascinating to watch him refine the style he had into something so direct, lyrical, and affecting. His stories seem to speak directly to you (at least, they do to me). Nnedi, Cat, and Chris are all being successful in their own ways, and watching them makes me think about what I want to do, how I want to be successful. Because their successes reflect their individual personalities, and so I have to think about what I can do that reflects mine. I could not be successful in their ways. But they give me a sense of the possibilities out there.

(If you haven't read their stories, you'll find links to their websites on this page. Go buy their books! You still need to buy presents, don't you? If not for others, then for yourself.)

But I called this post "Engaging the World," and that sort of engagement is not a passive activity. It doesn't mean simply paying attention to what other writers are doing. It means going out there (which many writers are not very good at doing – many of us are like deer, and prefer to stay in the shadows at the edge of the forest), joining organizations, being on panels at conventions. Putting your own ideas in front of the world, being willing to say what you think. Especially about writing, about where it is nowadays, where it needs to go. That takes a certain level of courage, because you will be contradicted and someone, and maybe a lot of someones, will say you're wrong. And you may be.

But I think it's important for writers to be engaged, with the world of other writers and, beyond that, with the world of their readers. Because the readers are what it's all about, finally. (If you're a reader, you're what this is all about, finally. If I don't reach you, if I don't engage with you, I've failed.)

Reading this post over, trying to correct misspellings, mistakes, I realize how much more random it is than my usual posts. That's because there's a though behind it that I haven't expressed, that I've withheld from you. It is this. I met a writer recently, one of the most talented I've met, who is not engaged in this way. And who, therefore, is not in touch with other writers or readers, and misses opportunities to make his writing stronger, and misses publication opportunities, and opportunities to bring his writing to readers who would enjoy it, be touched by it. He will never read this post, because he doesn't read such things, so it's as though I'm writing it completely in private, even though it can be read by the entire world. And so this post is a form of mourning for missed opportunities, for him and other writers I've known like him who are not engaged, and do not know their own possibilities. And it is a reminder to myself, and to you who are reading this, to engage, even when we feel like curling up in bed, under the fuzzy blanket (pictured in my last post, if you remember).

December 17, 2010

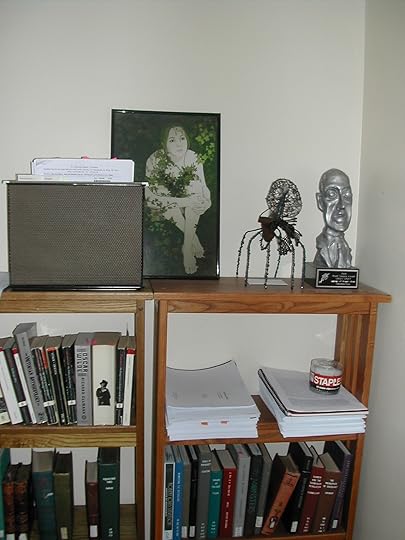

My Work Space

Terri Windling is one of my favorite writers and one of my favorite people in general (if she is a person, which I have long doubted – I suspect she's really the Fairy Queen in her mortal form). She has the most wonderful blog, and as soon as you look at it, you will realize that I stole the idea of William Morris wallpaper (get it? wallpaper!) from her, although mine is a sort of sage rather than taupe.

Well, Terri has a wonderful series on the blog, in which she is asking people to photograph their desks and posting the photographs. If you scroll down this post, you will see my desk.

When I saw this picture, I was a little sad, because my work space is so much sparer, and I have to admit so much more boring, than the work spaces of other people she's featured. It doesn't quite look like the work space of a creative person, does it? But it is what it is, and I thought on my own blog I would post some more pictures of where I work. Here they are:

These are two of my shelves, and you can see how messy they are. On top I have notebooks with stories I'm working on, and a picture I haven't yet hung up. That small black box is filled with contact information for people I know in the writing world, people I've met at conventions, etc. It's my box of professional contact information. I suggest that every writer have one.

Two more of my bookshelves, with Mr. Lovecraft Head (yes, that's my World Fantasy Award) and one of the most wonderful presents anyone has ever given me, the poet Elah Gal from "Child-Empress of Mars" sculpted by C. Jane Washburn. Also another picture (a digital one) I have not yet hung up.

And another view of the same shelves, showing the all-important basket with a fuzzy blanket in it, which I wrap around myself when I'm reading. These shelves, by the way, are currently my dissertation shelves, meaning that they are filled with library books and copies of my manuscript. May they someday be put to a nobler use!

This is the comfortable chair, with Dani, the bear I received for my first Christmas, and a pillow I sewed from William Morris fabric (can you see a theme emerging?), and my purse. (No, I did not straighten anything before taking these pictures. Perhaps I should have.) The book on the pillow is Kage Baker's The Hotel Under the Sand, which I am currently reading. The books on the arm of the chair are a set of John Carter of Mars novels, which I'm using to research a story I'm currently writing, on top of the notebooks in which I'm writing the story.

This is my desk, which was also shown on Terri's blog. The CDs stacked on the shelf, by the ancient boombox I salvaged from the basement of the apartment building where I used to live, are mostly Loreena McKennitt, music from the Renaissance, or experimental modern music (Eric Satie, Arvo Pärt, Morton Feldman).

And panning over, you get to . . .

My other desk, where I do anything that does not require a computer. The cabinet holds writing supplies, and in front of it is my new favorite thing in the world, my space heater. Because in a drafty old house in Massachusetts, it is never, ever warm enough.

And there you have it, my work space. If I owned this house, it would probably be fancier in some way. But it's functional, and here I write my stories and poems and essays. I suppose finally that's what counts, the output. Right?

December 16, 2010

One of Those Days

It's been one of those days. This morning I discovered that my laptop has been infected with spyware, so I can't use it until the spyware is removed. As a result, I could not do any work that required a laptop. I have a netbook, on which I am typing this post, but it's too small to type on well, and for someone who's used to touch-typing rather quickly, it's almost impossible to use for serious work. So I spent the day doing work for which I did not need a laptop: writing by hand part of a story I've promised to an anthology, and then reading through the first chapter of my dissertation. I need to revise the second chapter in the next two weeks, but in order to do that, I need to understand what I wrote in the first chapter. And I need to revise that as well. The final section on anthropology and the monster is not as strong as I want it to be.

So what to do? I promised myself that I would post every day, but my brain is empty of anything interesting and filled with all sorts of things you probably don't want to read about. Except that I did have some ideas about poetry, coming from having read some of the poems in Mythic Delirium 23.

Recently, I read a blog post about the best poetry books of 2010. It included some of the best lines from each book, and as I read them, I could feel a sort of sinking sensation. Based on those lines, there was almost nothing on the list that I would enjoy reading. And I thought, as I usually do when it comes to poetry, that it must be me – I must just have terrible taste in poetry. (Although I did want to read the Paul Muldoon and a new edition of Ezra Pound. Those sounded interesting.) I mean, when I read a standard Norton anthology of poetry, I love almost everything in it. And I love early modernism, Eliot and Auden and those guys. Even quite a lot of Stevens. And then something happens, and I find very little that I love anymore. Some Anne Sexton. Some Sylvia Plath. But so much of it goes flat for me.

But I do know what I like, what I respond to. As examples, I'm going to give you stanzas from two poems, both published in Mythic Delirium 23.

Ovid's Two Nightmares

by Sonya Taaffe

Not like Odysseus to his wife's ever-olive arms

nor like Agamemnon to the unapologetic knife

I return, the patron of exiles repatriated

windburned, ink-stained, grey-haired as the sea

tossing chips of rime on a black shore,

old Daedalus disbelieving the labyrinth's fall.

So many spilt words, so many missteps

like across my hands like shadows in the afternoon,

ripening lemon and bay, the grape's bitter leaves.

So many ghosts sent begging for salt and violets

hang back quivering in the August sun.

She Who Rules the Bitter Reaches

by C.S.E. Cooney

In avalanche silence, the unceasing breezes

Sculpt from the mountain a luminous keep

Lay carpets of snowflake and beds all of diamond

Preparing a nest for the Winterbird's sleep

Here she will live, in an ice-blooming vastness

Her breath forming opal of flesh and of stone

Here she will rest in this radiant fastness

A splendor of silver and feather and bone

If you want to read the rest of these poems, you'll have to order Mythic Delirium 23 . . .

What I want poetry to do, those two poems do for me. They send me somewhere only poetry can send me, to a place that is like the top of a mountain, where the air is clear. They give me a sense of joy, almost of ecstasy, as though my mind were dancing. That's what I want from poetry. I don't want it to make me think, although it can do that too. I want it to make me feel life coursing through me, as though I were breathing clear air at the top of a mountain, as though I were suddenly completely alive.

(Technically? In Taaffe it's the progression of the vowels and consonants: spilt, missteps. The way she arranges her vowels and consonants, that's the technical basis for the sensation the poem produces. In Cooney it's the rhythm, which is both regular and irregular, so that you're constantly juggling its irregularity, struggling to read it as regular. I'm not sure why, but that's a strong source of poetic pleasure.)

I think it's important, if you're a writer, to point out what you think is good, what gives you pleasure. It's a way of having and continuing a dialog about what is worthwhile in art. I started that with my last post about modernism, didn't I? And I suspect that I'll continue it. After all, I'm pretty opinionated about these things.