Rick Just's Blog, page 53

July 20, 2023

How do You Spell Cariboo?

There have been, occasionally, caribou in Idaho, and not just when Santa is flying over the state and, once again, pointedly skipping MY house. The caribou that until recently wandered in and out of Idaho in Boundary County, back and forth across the border with Canada, were the only caribou left in the Lower 48. The conservation effort that preserved them was abandoned and in early 2019 the last remaining caribou were removed to Canada.

Note that the caribou were in Boundary County. Caribou County does not have Caribou and never has in recorded history. So why would you name a county after caribou that never get closer than, say 480 miles away?

Residents are quick to tell you that Caribou County is not named after any sort of reindeer. And they are mostly correct. The county is named after “Carriboo” Jack Fairchild, a miner who was among those who first discovered gold on what is now called Caribou Mountain.

But one must wonder where Carriboo Jack got his name. As it turns out, the inveterate storyteller got his nickname because when questioned about the veracity of one of his stories he would often reply, “It is so, I will let you know I am from Cariboo.”

The Cariboo he was from was a mining district in British Columbia, where Fairchild had also worked a claim. The area retains the spelling, with a single “r” today. Carriboo had the extra “r” in his name because, I don’t know, he deserved it? And why don’t the Canadians spell it caribou?

The county in Idaho was called Carriboo until 1921, when someone decided to “correct” it. Caribou Mountian, Caribou City, and the Caribou National Forest all owe their name to Cariboo Jack, the story teller.

One story he often told was about his origins. “I was born in a blizzard snowdrift in the worst storm ever to hit Canada. I was bathed in a gold pan, suckled by a caribou, wrapped in a buffalo rug, and could whip any grizzly going before I was thirteen. That’s when I left home.” A guy like that can spell his name any way he wants.

Much of this story comes from a piece Ellen Carney wrote for the Caribou County website.

Note that the caribou were in Boundary County. Caribou County does not have Caribou and never has in recorded history. So why would you name a county after caribou that never get closer than, say 480 miles away?

Residents are quick to tell you that Caribou County is not named after any sort of reindeer. And they are mostly correct. The county is named after “Carriboo” Jack Fairchild, a miner who was among those who first discovered gold on what is now called Caribou Mountain.

But one must wonder where Carriboo Jack got his name. As it turns out, the inveterate storyteller got his nickname because when questioned about the veracity of one of his stories he would often reply, “It is so, I will let you know I am from Cariboo.”

The Cariboo he was from was a mining district in British Columbia, where Fairchild had also worked a claim. The area retains the spelling, with a single “r” today. Carriboo had the extra “r” in his name because, I don’t know, he deserved it? And why don’t the Canadians spell it caribou?

The county in Idaho was called Carriboo until 1921, when someone decided to “correct” it. Caribou Mountian, Caribou City, and the Caribou National Forest all owe their name to Cariboo Jack, the story teller.

One story he often told was about his origins. “I was born in a blizzard snowdrift in the worst storm ever to hit Canada. I was bathed in a gold pan, suckled by a caribou, wrapped in a buffalo rug, and could whip any grizzly going before I was thirteen. That’s when I left home.” A guy like that can spell his name any way he wants.

Much of this story comes from a piece Ellen Carney wrote for the Caribou County website.

Published on July 20, 2023 04:00

July 19, 2023

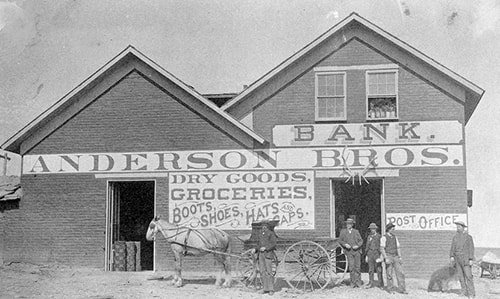

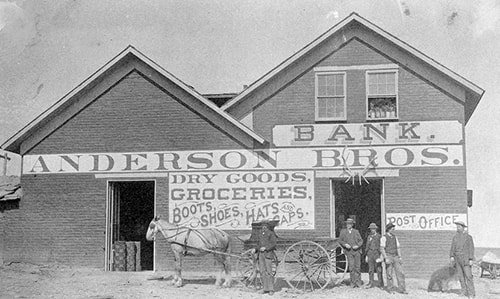

You Could get Everything at Anderson Brothers

In the 1860s it wasn’t wise to carry around a lot of money or gold in Idaho Territory. There was always someone ready to relieve you of it and, perhaps, your life if you hesitated to turn over your wealth.

Travelers between Corrine or Kelton, Utah, and Virginia City, Montana began asking the proprietors at the Anderson Brothers store at Taylor Bridge to hold their money for them, keeping it safe until they would return. Taylor Bridge was a toll bridge at what was first called Taylor Bridge, then Eagle Rock as it became a town, and Idaho Falls when it became a city. The Anderson Brothers store was one of the first to serve travelers going back and forth between the Montana mines and Utah supply points.

As the only spot for hundreds of square miles that had even a hint of security, Anderson Brothers began keeping goods and wealth as a favor to miners, often with no receipt except a handshake. The miners would drop back by in person when they were ready to claim their possessions, or they’d send a note by mail to the Anderson Brothers store requesting they send it on to another destination.

The Anderson Brothers began to worry about having money and gold sitting around on shelves beneath the counter, so they ordered a safe. That safe, and its continued use inspired them to open Anderson Brothers Bank.

The store became an unofficial post office the same way it became an unofficial bank, by being a place where people stopped on their way to someplace else.

The post office came about because people would leave letters in a box, hoping someone going more or less in the direction the letter was headed would pick it up and take it a few miles closer. People just pawed through the mail looking for a letter for them, or finding a letter for someone else that they could move on down the road a bit.

If that sounds like a haphazard way to run a post office, it sounded the same way to a postal inspector that happened through on his way to Montana. When he pointed this out to the Anderson Brothers, according to an article in the August 26, 1932 edition of the Post Register, one of them kicked the box of letters out the door and said, “There is your post office. Take it with you, and if you don’t like the way we do things around here we will throw you after the box.”

The inspector had a change of heart and decided they could continue their unauthorized post office, which they did until an official one was established a few years later when the railroad arrived.

Travelers between Corrine or Kelton, Utah, and Virginia City, Montana began asking the proprietors at the Anderson Brothers store at Taylor Bridge to hold their money for them, keeping it safe until they would return. Taylor Bridge was a toll bridge at what was first called Taylor Bridge, then Eagle Rock as it became a town, and Idaho Falls when it became a city. The Anderson Brothers store was one of the first to serve travelers going back and forth between the Montana mines and Utah supply points.

As the only spot for hundreds of square miles that had even a hint of security, Anderson Brothers began keeping goods and wealth as a favor to miners, often with no receipt except a handshake. The miners would drop back by in person when they were ready to claim their possessions, or they’d send a note by mail to the Anderson Brothers store requesting they send it on to another destination.

The Anderson Brothers began to worry about having money and gold sitting around on shelves beneath the counter, so they ordered a safe. That safe, and its continued use inspired them to open Anderson Brothers Bank.

The store became an unofficial post office the same way it became an unofficial bank, by being a place where people stopped on their way to someplace else.

The post office came about because people would leave letters in a box, hoping someone going more or less in the direction the letter was headed would pick it up and take it a few miles closer. People just pawed through the mail looking for a letter for them, or finding a letter for someone else that they could move on down the road a bit.

If that sounds like a haphazard way to run a post office, it sounded the same way to a postal inspector that happened through on his way to Montana. When he pointed this out to the Anderson Brothers, according to an article in the August 26, 1932 edition of the Post Register, one of them kicked the box of letters out the door and said, “There is your post office. Take it with you, and if you don’t like the way we do things around here we will throw you after the box.”

The inspector had a change of heart and decided they could continue their unauthorized post office, which they did until an official one was established a few years later when the railroad arrived.

Published on July 19, 2023 04:00

July 18, 2023

Chief Washakie Received many Honors

Back before there was an Idaho, or a Wyoming, or pick your state, there was a Shoshoni land that stretched irregularly from Death Valley north to where Salmon is today, and east into the Wind River Range. It encompassed much of southern Idaho and northern Utah.

It was into this vast territory that a boy was born, known then as Pinaquanah and today as Washakie. He would become a leader of the Shoshone people and would be richly honored. He may have met his first white men in 1811 along the Boise River when Wilson Hunt’s party was on its way through to Astoria. When he was 16 he met Jim Bridger. They were friends for many years and Bridger married one of Washakie’s daughters in 1850.

Washakie became the chief of the Eastern Snakes in the late 1800s. His people were friendly with fur traders and later soldiers. He and his warriors helped General George Crook defeat the Sioux following Custer’s defeat at Little Big Horn.

Chief Washakie, and other tribal chiefs, signed the Fort Bridger treaties of 1863 and 1868, establishing large reservations for the Shoshone people. The Eastern Shoshones, Washakie’s band, initially received more than three million acres in the Wind River Country. In most such treaties between the U.S. and Indian tribes, the tribes saw their lands dramatically reduced in size. Today the Wind River Reservation is about 2.2 million acres.

Washakie loved gambling and was a renowned artist, using hides as the medium on which he painted. He was interested in religion and became first an Episcopalian, then later in his life, as he became friends with Brigham Young, a convert to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. He believed deeply in education. Today’s Chief Washakie Foundation carries on his tradition of educating his people with his great-great grandson as its head.

Chief Washakie was honored in many ways. In 1878 Fort Washakie, in Wyoming, became the first—and to date—only U.S. military outpost to be named after a Native American. Wyoming’s Washakie County is named for him. Washakie, Utah, now a ghost town, carries his name. The dining hall at the University of Wyoming is Washakie Hall. There’s a statue of the man in downtown Casper. More importantly, Chief Washakie is depicted in a bronze sculpture in Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol building. Two ships have carried his name, the Liberty Ship SS Chief Washakie commissioned during World War II, and the USS Washakie, a U.S. Navy harbor tug. When he died in 1900 he was given a full military funeral.

It was into this vast territory that a boy was born, known then as Pinaquanah and today as Washakie. He would become a leader of the Shoshone people and would be richly honored. He may have met his first white men in 1811 along the Boise River when Wilson Hunt’s party was on its way through to Astoria. When he was 16 he met Jim Bridger. They were friends for many years and Bridger married one of Washakie’s daughters in 1850.

Washakie became the chief of the Eastern Snakes in the late 1800s. His people were friendly with fur traders and later soldiers. He and his warriors helped General George Crook defeat the Sioux following Custer’s defeat at Little Big Horn.

Chief Washakie, and other tribal chiefs, signed the Fort Bridger treaties of 1863 and 1868, establishing large reservations for the Shoshone people. The Eastern Shoshones, Washakie’s band, initially received more than three million acres in the Wind River Country. In most such treaties between the U.S. and Indian tribes, the tribes saw their lands dramatically reduced in size. Today the Wind River Reservation is about 2.2 million acres.

Washakie loved gambling and was a renowned artist, using hides as the medium on which he painted. He was interested in religion and became first an Episcopalian, then later in his life, as he became friends with Brigham Young, a convert to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. He believed deeply in education. Today’s Chief Washakie Foundation carries on his tradition of educating his people with his great-great grandson as its head.

Chief Washakie was honored in many ways. In 1878 Fort Washakie, in Wyoming, became the first—and to date—only U.S. military outpost to be named after a Native American. Wyoming’s Washakie County is named for him. Washakie, Utah, now a ghost town, carries his name. The dining hall at the University of Wyoming is Washakie Hall. There’s a statue of the man in downtown Casper. More importantly, Chief Washakie is depicted in a bronze sculpture in Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol building. Two ships have carried his name, the Liberty Ship SS Chief Washakie commissioned during World War II, and the USS Washakie, a U.S. Navy harbor tug. When he died in 1900 he was given a full military funeral.

Published on July 18, 2023 04:00

July 17, 2023

A Pulling Contest Named a Landmark

The Google Earth satellite photo of Pulling Hill on the northeast side of the Presto Bench a few miles outside of Firth looks a little like an art installation. Motorcycles installed it, for the most part. I helped with that as a kid. In the winter the hillsides were where everyone went to sleigh and sometimes snowmobile.

Pulling Hill always seemed like an odd name to me. It turns out that pulling contests were often run between cars in the early days of same. Maybe some of those contests involved pulling something, but this one was all about a hill climb.

It seems that a car salesman from Boise (even then a metropolis that engendered great suspicion in rural parts of the state) walked into Rasumus Hansen’s 3A Garage in Blackfoot. A disagreement ensued over which car was better at climbing hills, the salesman’s car or Rass Hansen’s car. Sadly, the make and model of each is lost to history or we could take side bets.

They set a day for the contest and agreed that the winner would receive $100 from the loser. When the day came a large crowd was on hand to witness the event. Leading up to the main event a few other cars tried the hill with varying results. Rass Hansen went first in the main climb, getting only part-way up the hill. The man from Boise chugged all the way to the top in his car. However, upon inspection, it turned out the Boise man had modified his car for the occasion, something explicitly forbidden in the bet. Hansen’s car was declared the winner by default and the reputation of people from Boise dropped another notch.

From that day forward, the steep hill on Presto Bench became Pulling Hill. Many more matches of automobile fitness followed, as did motorcycle races, bucking horse contests, and submarine races. That last is actually a local term for necking more appropriately applied when the occupants of an automobile were parked near the Firth River Bottoms overlooking the Snake River, but the sport was much the same.

Pulling Hill became a county recreation site in 1970. The official name for the 25.5 acre site is Presto Park.

Thanks to Snake River Echoes, the quarterly publication of the Upper Snake River Valley Historical Society for much of the information in this post, found in the Spring 1985 edition in an article by Ruby Hansen Hanft.

Pulling Hill always seemed like an odd name to me. It turns out that pulling contests were often run between cars in the early days of same. Maybe some of those contests involved pulling something, but this one was all about a hill climb.

It seems that a car salesman from Boise (even then a metropolis that engendered great suspicion in rural parts of the state) walked into Rasumus Hansen’s 3A Garage in Blackfoot. A disagreement ensued over which car was better at climbing hills, the salesman’s car or Rass Hansen’s car. Sadly, the make and model of each is lost to history or we could take side bets.

They set a day for the contest and agreed that the winner would receive $100 from the loser. When the day came a large crowd was on hand to witness the event. Leading up to the main event a few other cars tried the hill with varying results. Rass Hansen went first in the main climb, getting only part-way up the hill. The man from Boise chugged all the way to the top in his car. However, upon inspection, it turned out the Boise man had modified his car for the occasion, something explicitly forbidden in the bet. Hansen’s car was declared the winner by default and the reputation of people from Boise dropped another notch.

From that day forward, the steep hill on Presto Bench became Pulling Hill. Many more matches of automobile fitness followed, as did motorcycle races, bucking horse contests, and submarine races. That last is actually a local term for necking more appropriately applied when the occupants of an automobile were parked near the Firth River Bottoms overlooking the Snake River, but the sport was much the same.

Pulling Hill became a county recreation site in 1970. The official name for the 25.5 acre site is Presto Park.

Thanks to Snake River Echoes, the quarterly publication of the Upper Snake River Valley Historical Society for much of the information in this post, found in the Spring 1985 edition in an article by Ruby Hansen Hanft.

Published on July 17, 2023 04:00

July 16, 2023

A Well-Schooled Mountain Man

Idaho has long sent a siren song to people who want to escape the world. “Buckskin Bill,” sometimes called the Last of the Mountain Men, may be the best known.

We associate mountain men with the fur-trapping era of the 1800s. Sylvan Hart, who became known as “Buckskin Bill,” turned into a man of the mountains nearly a century later in 1932. He started his adventure as a way to ride out the depression. He stayed for the rest of his life.

Hart believed in education. He attended four colleges, getting a B.A. in English Literature from the University of Oklahoma. It was for his continuing education that he became a hermit living on the banks of the Salmon River. In Cort Conley’s excellent book, Idaho Loners, he quotes Hart as saying, “I wasn’t trying to run away from anything. I was Just a natural born student, and I could study there, investigate for myself, and I could experiment with different things. I’m not going to give up on education. I doesn’t pay to stop. Once you get really dumb, there’s no redemption for you.”

Hart, along with his father, Artie, picked a spot on Five Mile Bar to live off the land. Artie eventually had enough of the Salmon River Country and moved into town. Sylvan stayed on, winter after long winter, spending six months at a time without seeing a soul.

“Buckskin Bill” tended a large garden, hunted, and panned a little gold for his living. He got his name from Don Oberbillig, who lived at Mackay Bar three miles down the river. Buckskin was what Hart wore. Where “Bill” came from is not exactly clear. Alliteration probably played a part.

Hermits are famously drop-outs from society. Hart ran against type in that respect. When he heard about Pearl Harbor, a few months after the event, he hiked out to Grangeville to join the Army. They wouldn’t have him because of an enlarged heart and because at 35, he was a little old for the front lines.

Hart still wanted to help in the war effort. He got himself to Wichita, Kansas where he took a job as a toolmaker with Boeing.

In 1942, with the war roaring, the Army lowered its standards for inductees. They inducted Sylvan Hart and posted him to Amchitka in the Aleutian Islands. The Japanese had taken over the remote territory. Hart’s group was meant to oust them, but they left before he saw any action. Oddly, the FBI had been looking for him, thinking he was a draft dodger.

The Army sent Hart to Colorado, where he helped develop a top-secret bombsight.

Shortly after the war ended, he drifted back to his home in Idaho. Back to gardening, hunting, fishing, and making. He made everything he used, from kitchen utensils to guns. His flintlock rifles, which took a year to make, were hand-rifled and hand-bored, with elaborately carved wooden stocks.

Buckskin Bill’s brush with the FBI was a mistake. His brush with the IRS was purposeful bureaucracy. He didn’t care much for money. Many of his checks from his Army days went uncashed so long that they expired. He didn’t feel an obligation to pay taxes since, by his estimation, he didn’t make $500 a year. The IRS had a different math. They sent him threatening letters because of his lack of filings. So, Sylvan Hart turned himself in, arriving in Boise in full “Buckskin Bill” regalia.

Hart set up camp in the IRS office. He rolled out his sleeping bag on the floor and brewed a pot of tea. A supervisor was summoned. Bill offered him a cup of tea. He explained to the IRS that he was ready to go to prison, if need be. He had brought along a supply of pemmican for his stay. Recognizing that this wasn’t your average tax scofflaw, IRS officials sent him back to Five Mile Bar and never bothered him again.

But the world wouldn’t leave Buckskin Bill alone. In 1966, a writer for Sports Illustrated showed up on his doorstep. The resulting article, titled, “The Last of the Mountain Men,” assured that Buckskin Bill would never be anonymous again. An expanded version of the story came out in book form a few years later.

This new-found fame didn’t bother Sylvan Hart, the sometimes hermit. He loved to regale rafters and hikers with stories about his life in the Salmon River Country. Buckskin Bill became a celebrity of the backcountry, enjoying his solitude and fame in equal measures.

In 1980, Buckskin Bill passed away, making it just shy of 74 years. Friends conducted his funeral in Grangeville, then flew his body to Mackay Bar to be hauled upriver by boat. He was interred on his Five Mile Bar property, which remains a popular spot for rafters to visit today.

We associate mountain men with the fur-trapping era of the 1800s. Sylvan Hart, who became known as “Buckskin Bill,” turned into a man of the mountains nearly a century later in 1932. He started his adventure as a way to ride out the depression. He stayed for the rest of his life.

Hart believed in education. He attended four colleges, getting a B.A. in English Literature from the University of Oklahoma. It was for his continuing education that he became a hermit living on the banks of the Salmon River. In Cort Conley’s excellent book, Idaho Loners, he quotes Hart as saying, “I wasn’t trying to run away from anything. I was Just a natural born student, and I could study there, investigate for myself, and I could experiment with different things. I’m not going to give up on education. I doesn’t pay to stop. Once you get really dumb, there’s no redemption for you.”

Hart, along with his father, Artie, picked a spot on Five Mile Bar to live off the land. Artie eventually had enough of the Salmon River Country and moved into town. Sylvan stayed on, winter after long winter, spending six months at a time without seeing a soul.

“Buckskin Bill” tended a large garden, hunted, and panned a little gold for his living. He got his name from Don Oberbillig, who lived at Mackay Bar three miles down the river. Buckskin was what Hart wore. Where “Bill” came from is not exactly clear. Alliteration probably played a part.

Hermits are famously drop-outs from society. Hart ran against type in that respect. When he heard about Pearl Harbor, a few months after the event, he hiked out to Grangeville to join the Army. They wouldn’t have him because of an enlarged heart and because at 35, he was a little old for the front lines.

Hart still wanted to help in the war effort. He got himself to Wichita, Kansas where he took a job as a toolmaker with Boeing.

In 1942, with the war roaring, the Army lowered its standards for inductees. They inducted Sylvan Hart and posted him to Amchitka in the Aleutian Islands. The Japanese had taken over the remote territory. Hart’s group was meant to oust them, but they left before he saw any action. Oddly, the FBI had been looking for him, thinking he was a draft dodger.

The Army sent Hart to Colorado, where he helped develop a top-secret bombsight.

Shortly after the war ended, he drifted back to his home in Idaho. Back to gardening, hunting, fishing, and making. He made everything he used, from kitchen utensils to guns. His flintlock rifles, which took a year to make, were hand-rifled and hand-bored, with elaborately carved wooden stocks.

Buckskin Bill’s brush with the FBI was a mistake. His brush with the IRS was purposeful bureaucracy. He didn’t care much for money. Many of his checks from his Army days went uncashed so long that they expired. He didn’t feel an obligation to pay taxes since, by his estimation, he didn’t make $500 a year. The IRS had a different math. They sent him threatening letters because of his lack of filings. So, Sylvan Hart turned himself in, arriving in Boise in full “Buckskin Bill” regalia.

Hart set up camp in the IRS office. He rolled out his sleeping bag on the floor and brewed a pot of tea. A supervisor was summoned. Bill offered him a cup of tea. He explained to the IRS that he was ready to go to prison, if need be. He had brought along a supply of pemmican for his stay. Recognizing that this wasn’t your average tax scofflaw, IRS officials sent him back to Five Mile Bar and never bothered him again.

But the world wouldn’t leave Buckskin Bill alone. In 1966, a writer for Sports Illustrated showed up on his doorstep. The resulting article, titled, “The Last of the Mountain Men,” assured that Buckskin Bill would never be anonymous again. An expanded version of the story came out in book form a few years later.

This new-found fame didn’t bother Sylvan Hart, the sometimes hermit. He loved to regale rafters and hikers with stories about his life in the Salmon River Country. Buckskin Bill became a celebrity of the backcountry, enjoying his solitude and fame in equal measures.

In 1980, Buckskin Bill passed away, making it just shy of 74 years. Friends conducted his funeral in Grangeville, then flew his body to Mackay Bar to be hauled upriver by boat. He was interred on his Five Mile Bar property, which remains a popular spot for rafters to visit today.

Published on July 16, 2023 04:00

July 15, 2023

A Protest about a Road

If you’ve been reading these history posts for a while, you know that I’m interested in how things got their names. I’ve done posts on how the state got its name, where county names came from, and why cities in Idaho have their names.

So, you would not be surprised that the name Protest Road in Boise has always intrigued me. What protest was it commemorating? Women’s suffrage, perhaps? Something to do with a labor strike from back in the Wobbly days? Maybe it came from the civil rights struggle.

As it turns out, Protest Road is named such because of a protest. Over a road. That road.

In March of 1950 stakes were going up in South Boise for a new road that would connect the area to a new fire station being built on the rim above. That wasn’t a surprise. Residents had voted to construct such a road. But in the mind of a citizen protest committee, the stakes indicated the road was being planned in the wrong place. The road as staked out would send fire engines to Boise Avenue, where they would have to reverse their direction and come back into South Boise along a narrow and twisting thoroughfare. They had voted on a route that would allow engines to access South Boise more directly.

More than 500 citizens showed up in early community meetings on the matter. They voted to form the South Boise Citizens Protest Committee. Ultimately a sensible alignment of the road was proposed that seemed to work for everyone. It was decided that the road should be called Protest Road in commemoration of the efforts of the Committee.

This wasn’t the first time a citizen protest committee from South Boise had been formed. I found an article from 1907 in the Statesman headlined “Citizens of South Boise to Hold an Indignation Meeting Next Tuesday Night.” That “indignation” was also over a transportation issue, poor rail service to the area.

It’s not surprising that residents take their transportation issues seriously in South Boise. Transportation was there before there was a South Boise. The Oregon Trail runs through that section of town.

Thanks to Barbara Perry Bauer for her help with research on this post and for her delightful little book South Boise Scrapbook.

So, you would not be surprised that the name Protest Road in Boise has always intrigued me. What protest was it commemorating? Women’s suffrage, perhaps? Something to do with a labor strike from back in the Wobbly days? Maybe it came from the civil rights struggle.

As it turns out, Protest Road is named such because of a protest. Over a road. That road.

In March of 1950 stakes were going up in South Boise for a new road that would connect the area to a new fire station being built on the rim above. That wasn’t a surprise. Residents had voted to construct such a road. But in the mind of a citizen protest committee, the stakes indicated the road was being planned in the wrong place. The road as staked out would send fire engines to Boise Avenue, where they would have to reverse their direction and come back into South Boise along a narrow and twisting thoroughfare. They had voted on a route that would allow engines to access South Boise more directly.

More than 500 citizens showed up in early community meetings on the matter. They voted to form the South Boise Citizens Protest Committee. Ultimately a sensible alignment of the road was proposed that seemed to work for everyone. It was decided that the road should be called Protest Road in commemoration of the efforts of the Committee.

This wasn’t the first time a citizen protest committee from South Boise had been formed. I found an article from 1907 in the Statesman headlined “Citizens of South Boise to Hold an Indignation Meeting Next Tuesday Night.” That “indignation” was also over a transportation issue, poor rail service to the area.

It’s not surprising that residents take their transportation issues seriously in South Boise. Transportation was there before there was a South Boise. The Oregon Trail runs through that section of town.

Thanks to Barbara Perry Bauer for her help with research on this post and for her delightful little book South Boise Scrapbook.

Published on July 15, 2023 04:00

July 14, 2023

A Lake and a Creek Pretending

Sometimes place names are a little deceptive, and deliberately so.

The town of Cascade was founded in 1912, consolidating the communities of Van Wyck, Thunder City, and Crawford, according to Lalia Boone’s Idaho Place Names. The town was named for nearby Cascade Falls. Cascade Dam was completed by the Bureau of Reclamation in 1948, creating Cascade Reservoir and effectively drowning the falls the reservoir was named for.

Cascade Reservoir hosted boaters and anglers for more than 50 years until 1999, when Cascade Reservoir became Lake Cascade. So, we have a lake that isn’t a lake named for a waterfall which the (not) lake destroyed.

I get it. I’m not complaining about the dam or the reservoir, only noting the irony that can sometimes come about when naming something.

Cascade Reservoir became Lake Cascade because local tourism promoters thought it sounded better. They were right. Lake Cascade sounds like something nature created and is thus more enticing than what we may picture in our minds when we think of a reservoir.

Another example of this bait and switch is Logger Creek in Boise. Logger Creek sounds much more scenic than Logger Ditch. Ditch it is, though. It was created in 1865 to power a waterwheel flour mill, which later became a sawmill. The ditch was then used to float logs to the mill. Much of Logger Creek was filled in years later, but the remaining section, which pulls water from the Boise River now does little else but take that water for a scenic ride along the Greenbelt before diverting it back into the river.

The town of Cascade was founded in 1912, consolidating the communities of Van Wyck, Thunder City, and Crawford, according to Lalia Boone’s Idaho Place Names. The town was named for nearby Cascade Falls. Cascade Dam was completed by the Bureau of Reclamation in 1948, creating Cascade Reservoir and effectively drowning the falls the reservoir was named for.

Cascade Reservoir hosted boaters and anglers for more than 50 years until 1999, when Cascade Reservoir became Lake Cascade. So, we have a lake that isn’t a lake named for a waterfall which the (not) lake destroyed.

I get it. I’m not complaining about the dam or the reservoir, only noting the irony that can sometimes come about when naming something.

Cascade Reservoir became Lake Cascade because local tourism promoters thought it sounded better. They were right. Lake Cascade sounds like something nature created and is thus more enticing than what we may picture in our minds when we think of a reservoir.

Another example of this bait and switch is Logger Creek in Boise. Logger Creek sounds much more scenic than Logger Ditch. Ditch it is, though. It was created in 1865 to power a waterwheel flour mill, which later became a sawmill. The ditch was then used to float logs to the mill. Much of Logger Creek was filled in years later, but the remaining section, which pulls water from the Boise River now does little else but take that water for a scenic ride along the Greenbelt before diverting it back into the river.

Published on July 14, 2023 04:00

July 13, 2023

Mr. Spud

J.R. Simplot was not born in Idaho. He was born in—wait for it—Iowa, thus further confusing those who can’t tell the two states apart.

Simplot didn’t stay in Iowa long. His parents brought him and his six siblings to a little farm near Declo, Idaho when he was about a year old. One could say he left a bit of a mark on the state’s business history.

J.R. made his first money from feeding pigs, and then kept making it. And making it. He lived in a time when it wasn’t unusual to quit school after completing the eighth grade, which was what he did. Most dropouts didn’t go on to become the largest shipper of fresh potatoes in the nation, or become a phosphate king, which he also did. The story of how his company developed a method of freezing French fried potatoes, and how he did a handshake deal with Ray Kroc to supply fries to McDonalds is well known.

J.R. liked to say that he was big in chips. He meant potato chips, but he also meant computer chips. He was key in the early days of computer chip maker Micron Technology. Simplot gave the Parkinson brothers of Blackfoot $1 million in the early days of the company, then put in another $20 million to help Micron build its first fabrication plant in Boise.

J.R. Simplot died in 2008 at age 99. His company recently built a new headquarters building in Boise, and the J.R. Simplot Foundation built something called JUMP next door. That stands for Jack’s Urban Meeting Place. It’s the site of public performances in the arts, various makers studios, giant slippery slides, and a bunch of tractors. That description doesn’t do it justice. None does. You have to see it yourself to understand the vision. It’s worth a visit for the tractors alone. About 50 antique tractors from J.R. Simplot’s personal collection are on display at JUMP in downtown Boise.

The photo of J.R. Simplot with some unidentified kind of tuber is from the Idaho State Historical Society’s digital collection.

Simplot didn’t stay in Iowa long. His parents brought him and his six siblings to a little farm near Declo, Idaho when he was about a year old. One could say he left a bit of a mark on the state’s business history.

J.R. made his first money from feeding pigs, and then kept making it. And making it. He lived in a time when it wasn’t unusual to quit school after completing the eighth grade, which was what he did. Most dropouts didn’t go on to become the largest shipper of fresh potatoes in the nation, or become a phosphate king, which he also did. The story of how his company developed a method of freezing French fried potatoes, and how he did a handshake deal with Ray Kroc to supply fries to McDonalds is well known.

J.R. liked to say that he was big in chips. He meant potato chips, but he also meant computer chips. He was key in the early days of computer chip maker Micron Technology. Simplot gave the Parkinson brothers of Blackfoot $1 million in the early days of the company, then put in another $20 million to help Micron build its first fabrication plant in Boise.

J.R. Simplot died in 2008 at age 99. His company recently built a new headquarters building in Boise, and the J.R. Simplot Foundation built something called JUMP next door. That stands for Jack’s Urban Meeting Place. It’s the site of public performances in the arts, various makers studios, giant slippery slides, and a bunch of tractors. That description doesn’t do it justice. None does. You have to see it yourself to understand the vision. It’s worth a visit for the tractors alone. About 50 antique tractors from J.R. Simplot’s personal collection are on display at JUMP in downtown Boise.

The photo of J.R. Simplot with some unidentified kind of tuber is from the Idaho State Historical Society’s digital collection.

Published on July 13, 2023 04:00

July 12, 2023

A Mexican Packer Made His Mark

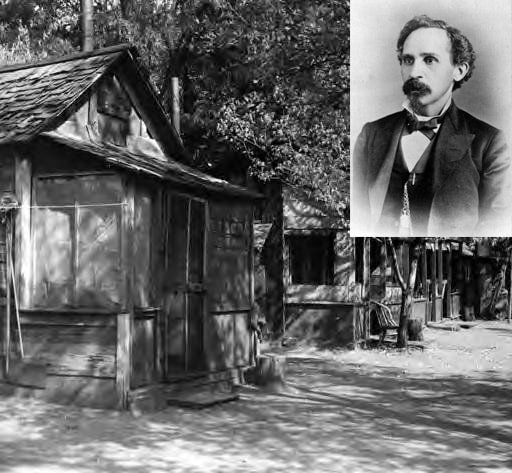

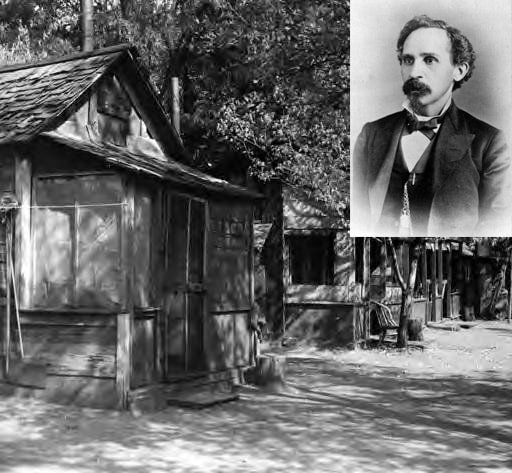

When you were a miner in the early days of Idaho, you couldn’t just order up supplies from Amazon. There were no planes, no trucks, and most importantly, no roads. Everything had to be packed in to remote areas, usually by a string of mules. If you had a big job, you counted on Jesus Urquides to get what you needed where you needed it.

Urquides was born in 1833, perhaps in San Francisco, as many sources claim, or perhaps in Sonora, Mexico, as he once said in a magazine interview. He is often called Boise’s Basque packer, though he was probably Mexican, not Basque.

Urquides started freighting in 1850, taking supplies to the Forty-niners—the miners. The football team of the same name would come along about a hundred years later.

He bragged that there was not a camp of any size between California and Montana that he had not packed supplies to. He packed a lot of whiskey, ammunition for the military, railroad track, and the first mill to the mine at Thunder Mountain. We’re not talking about a couple of mules here. Urquides would have trains of 65 or more.

Probably his most famous packing feat came when he was called on to take a roll of wire for a tram to the Yellow Jacket mine outside of Challis. A roll of wire doesn’t seem like much, but it weighed 10,000 pounds. It had to be distributed in coils across 35 mules working three abreast. The tricky thing was that you couldn’t simply cut it and make a couple of tidy rolls for each mule. Cutting the wire, then splicing it back together would make it too dangerous to use on a tram. Urquides’ solution was to wrap each mule in a coil of wire it could handle—maybe up to 300 pounds—then string it on to the next mule, and on and on. Of course, if one mule took a tumble, he’d drag other mules down with him. This happened several times. Each time Urquides and his men would get the mules back on their feet, make sure the wire was okay, then set off again. He only had 70 miles to travel, much of it up and down mountains and through canyons.

Ridiculous as the arrangement seems, Urquides made it work. He delivered the unbroken wire to its destination. He once commented, “I never coveted another job like that.”

In the late 1870s Urquides built about 30 one-room buildings in Boise behind his home at 115 Main, to house his drivers and wranglers. It became known as “Spanish Village.” This shanty town would last about a hundred years, furnishing low-rent housing long past the days of 65-mule strings.

Jesus Urquides died in 1928 at age 95 and is buried in Pioneer Cemetery, not far from his Boise home. The photo of Spanish Village and Urquides are courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Urquides was born in 1833, perhaps in San Francisco, as many sources claim, or perhaps in Sonora, Mexico, as he once said in a magazine interview. He is often called Boise’s Basque packer, though he was probably Mexican, not Basque.

Urquides started freighting in 1850, taking supplies to the Forty-niners—the miners. The football team of the same name would come along about a hundred years later.

He bragged that there was not a camp of any size between California and Montana that he had not packed supplies to. He packed a lot of whiskey, ammunition for the military, railroad track, and the first mill to the mine at Thunder Mountain. We’re not talking about a couple of mules here. Urquides would have trains of 65 or more.

Probably his most famous packing feat came when he was called on to take a roll of wire for a tram to the Yellow Jacket mine outside of Challis. A roll of wire doesn’t seem like much, but it weighed 10,000 pounds. It had to be distributed in coils across 35 mules working three abreast. The tricky thing was that you couldn’t simply cut it and make a couple of tidy rolls for each mule. Cutting the wire, then splicing it back together would make it too dangerous to use on a tram. Urquides’ solution was to wrap each mule in a coil of wire it could handle—maybe up to 300 pounds—then string it on to the next mule, and on and on. Of course, if one mule took a tumble, he’d drag other mules down with him. This happened several times. Each time Urquides and his men would get the mules back on their feet, make sure the wire was okay, then set off again. He only had 70 miles to travel, much of it up and down mountains and through canyons.

Ridiculous as the arrangement seems, Urquides made it work. He delivered the unbroken wire to its destination. He once commented, “I never coveted another job like that.”

In the late 1870s Urquides built about 30 one-room buildings in Boise behind his home at 115 Main, to house his drivers and wranglers. It became known as “Spanish Village.” This shanty town would last about a hundred years, furnishing low-rent housing long past the days of 65-mule strings.

Jesus Urquides died in 1928 at age 95 and is buried in Pioneer Cemetery, not far from his Boise home. The photo of Spanish Village and Urquides are courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection.

Published on July 12, 2023 04:00

July 11, 2023

Idaho's Oryctodromeus

Idaho’s newest state symbol is also its oldest. Designated Idaho’s State Dinosaur in 2023, Oryctodromeus (or-ik-tow-drohm-ee-us) lived about 98 million years ago during the Cretaceous Period. That makes Idaho’s State Fossil, the Hagerman Horse, a relative newcomer, having lived here about 3.5 million years ago.

Paleontologist Dr. L. J. Krumenacker, an instructor at the College of Eastern Idaho, found the first fossilized remains of Oryctodromeus in the Caribou-Targhee National Forest in 2006. It was a lucky find since dinosaur fossils are rare in Idaho. Even so, Oryctodromeus is the most common dinosaur in the state.

Oryctodromeus was a burrowing dinosaur, so far the first to be discovered in the world. Oryctodromeus means “digging runner.” They would have been good at both. The herbivore’s burrows were large since the dinosaurs stood about 3 feet tall, weighed between 50 and 70 pounds, and were nearly 11 feet long. Most of that length—about 2/3 of it—was made up of tail.

White Pine Charter School students in Ammon convinced lawmakers to add Oryctodromeus to the state’s list of symbols. So far, fossils of this dinosaur have been found only in eastern Idaho and the southwest corner of Montana.

Oryctodromeus. (2022, September 18). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oryctod...

Oryctodromeus. (2022, September 18). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oryctod...

Paleontologist Dr. L. J. Krumenacker, an instructor at the College of Eastern Idaho, found the first fossilized remains of Oryctodromeus in the Caribou-Targhee National Forest in 2006. It was a lucky find since dinosaur fossils are rare in Idaho. Even so, Oryctodromeus is the most common dinosaur in the state.

Oryctodromeus was a burrowing dinosaur, so far the first to be discovered in the world. Oryctodromeus means “digging runner.” They would have been good at both. The herbivore’s burrows were large since the dinosaurs stood about 3 feet tall, weighed between 50 and 70 pounds, and were nearly 11 feet long. Most of that length—about 2/3 of it—was made up of tail.

White Pine Charter School students in Ammon convinced lawmakers to add Oryctodromeus to the state’s list of symbols. So far, fossils of this dinosaur have been found only in eastern Idaho and the southwest corner of Montana.

Oryctodromeus. (2022, September 18). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oryctod...

Oryctodromeus. (2022, September 18). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oryctod...

Published on July 11, 2023 04:00