Rick Just's Blog, page 54

July 10, 2023

Plastic Potatoes are Everywhere

Brown plastic potato pins are ubiquitous in Idaho. Don't you have one? The Idaho Potato Commission will sell you a bag of 50 for $7. It was that commission, specifically its director Jay Sherlock, that came up with the idea for the pins.

It was 1965 and the Girl Scouts were having their famous Girl Scout Roundup at Farragut State Park. Idaho was famous for potatoes, but the girls were disappointed because they couldn’t see them growing in North Idaho. As quoted in a 1970 Idaho Statesman interview, Sherlock said that “Idaho First National Bank scraped up some potato banks and gave them to the girls as souvenirs.” They didn’t get pins, though.

Sherlock remembered a pickle company from his childhood that had distributed pickle pins, so he decided to borrow that idea. By 1967, when the World Boy Scout Jamboree came to Farragut, the Idaho Potato Commission was ready with plastic potato pins. They have distributed, conservatively, 2.5 bajillion of them since.

It was 1965 and the Girl Scouts were having their famous Girl Scout Roundup at Farragut State Park. Idaho was famous for potatoes, but the girls were disappointed because they couldn’t see them growing in North Idaho. As quoted in a 1970 Idaho Statesman interview, Sherlock said that “Idaho First National Bank scraped up some potato banks and gave them to the girls as souvenirs.” They didn’t get pins, though.

Sherlock remembered a pickle company from his childhood that had distributed pickle pins, so he decided to borrow that idea. By 1967, when the World Boy Scout Jamboree came to Farragut, the Idaho Potato Commission was ready with plastic potato pins. They have distributed, conservatively, 2.5 bajillion of them since.

Published on July 10, 2023 04:00

July 9, 2023

Winning the War on Skis

Idaho contributed to the war effort during World War II as the site of Farragut Naval Training Station, where more than 292,000 “boots” got their training. There was another training base proposed for Idaho about the same time. The Army even started construction on the site.

Farragut was perfect for the Navy because of Lake Pend Oreille. The second base would be on a lake, too, but it wasn’t the lake that made the site “perfect.” M.S. Benedict, Targhee National Forest Supervisor at the time, was quoted as saying, “The weather is severe with sub-zero temperatures for most of the winter. The area has about 4 feet of snow and the many slopes in the area are ideal for training ski troops. There is mountainous country, too, which could be used for toughening soldiers.” Benedict also counted the “high velocity winds (that) sweep across the area” as a plus.

The War Department was looking for a place to train troops who would be experts at skiing and winter survival.

A 100,000-acre site surrounding Henrys Lake just a few miles from West Yellowstone, Montana was selected for the training center. The camp would host 35,000 troops and cost some $20 million to build.

The State of Idaho was on board with the plan. Gov. Chase Clark revealed that the Idaho Transportation Department had ordered a huge new rotary snow plow to keep the roads in the area of the proposed base open.

Construction contracts were let in 1941 and buildings started going up for the new base. Foundations and vaults appeared and the structures began to take shape.

Almost immediately the Army Quartermaster began to question much about the project from high rates paid for rental vehicles to confusion and a lack of direction for the construction.

When that “perfect” winter weather hit, all construction ceased. In the spring of 1942 salvageable materials were hauled off and demolition equipment was moved in to bring down the bones of the buildings.

The country was at war, so why the Army did what it did was kept secret. Did contractor issues kill the base so quickly? That seems unlikely.

Thomas Howell, who lives in Ashton, has done considerable research on this subject, he once had a website where I obtained the information for this short piece, but it seems to be down now. Howell has a theory that it was trumpeter swans that killed the base, and he provides some compelling information to back that up. There were only 140 adults and 69 cygnets in the Lower 48 at that time mostly at Montana’s Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge and the Railroad Ranch in Island Park (now Harriman State Park). Wildlife enthusiasts were not wild about the idea of introducing men shooting artillery into trumpeter swan habitat.

The concrete evidence of the ill-fated base can still be seen today near Henrys Lake State Park.

Farragut was perfect for the Navy because of Lake Pend Oreille. The second base would be on a lake, too, but it wasn’t the lake that made the site “perfect.” M.S. Benedict, Targhee National Forest Supervisor at the time, was quoted as saying, “The weather is severe with sub-zero temperatures for most of the winter. The area has about 4 feet of snow and the many slopes in the area are ideal for training ski troops. There is mountainous country, too, which could be used for toughening soldiers.” Benedict also counted the “high velocity winds (that) sweep across the area” as a plus.

The War Department was looking for a place to train troops who would be experts at skiing and winter survival.

A 100,000-acre site surrounding Henrys Lake just a few miles from West Yellowstone, Montana was selected for the training center. The camp would host 35,000 troops and cost some $20 million to build.

The State of Idaho was on board with the plan. Gov. Chase Clark revealed that the Idaho Transportation Department had ordered a huge new rotary snow plow to keep the roads in the area of the proposed base open.

Construction contracts were let in 1941 and buildings started going up for the new base. Foundations and vaults appeared and the structures began to take shape.

Almost immediately the Army Quartermaster began to question much about the project from high rates paid for rental vehicles to confusion and a lack of direction for the construction.

When that “perfect” winter weather hit, all construction ceased. In the spring of 1942 salvageable materials were hauled off and demolition equipment was moved in to bring down the bones of the buildings.

The country was at war, so why the Army did what it did was kept secret. Did contractor issues kill the base so quickly? That seems unlikely.

Thomas Howell, who lives in Ashton, has done considerable research on this subject, he once had a website where I obtained the information for this short piece, but it seems to be down now. Howell has a theory that it was trumpeter swans that killed the base, and he provides some compelling information to back that up. There were only 140 adults and 69 cygnets in the Lower 48 at that time mostly at Montana’s Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge and the Railroad Ranch in Island Park (now Harriman State Park). Wildlife enthusiasts were not wild about the idea of introducing men shooting artillery into trumpeter swan habitat.

The concrete evidence of the ill-fated base can still be seen today near Henrys Lake State Park.

Published on July 09, 2023 04:00

July 8, 2023

So Many Haydens

A reader asked where the name Hayden came from for Hayden Creek in North Idaho. It seemed like a simple request, and I found the answer quickly in Lalia Boone’s definitive Idaho Place Names. Probably. Her explanation for the name Hayden Creek referred to a creek in Lemhi County, not the one that flows into Hayden Lake. That Hayden Creek flows from Hayden Basin. The basin and creek were named for Jim Hayden who was an early packer and freighter in the area. Hayden’s claim to fame was peppered with gunfire. Bill Smith, who was one of the first to discover gold in Leesburg, was playing cards with Jim Hayden in 1871. There was a dispute about a hand. Smith took umbrage at Hayden and fired at the man. Hayden was said to be unarmed, but he found a gun somewhere and shot back, killing Smith. Hayden was acquitted when he went to trial. His relief at that was short-lived. Hayden was killed by Indians in Birch Creek Valley in 1877.

The Hayden creek our reader asked about flows into Hayden Lake in Kootenai County and is not mentioned in Boones book. The lake and town are named after Mathew Hayden so it follows that the creek probably also carries his name. Hayden was reportedly (wait for it…) playing cards with John Hager at Hager’s cabin. There was no gunplay involved with this one. The two men agreed to name the lake after the winner of a seven-up game. Hayden won.

But wait! There’s more! We can’t forget Hayden Peak in Owyhee County. It was named after Everett Hayden, a surveyor working for the Smithsonian Institution in the 1880s. Reportedly there was some local grumbling at the time because Hayden had never even been near the peak.

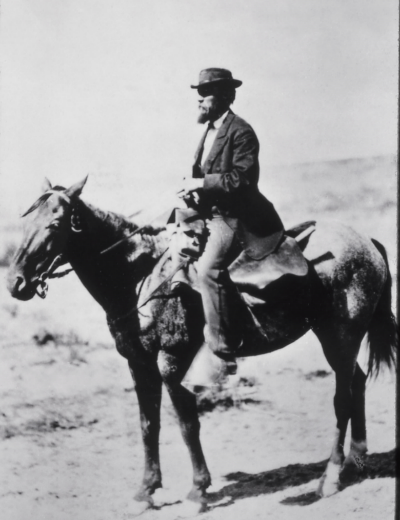

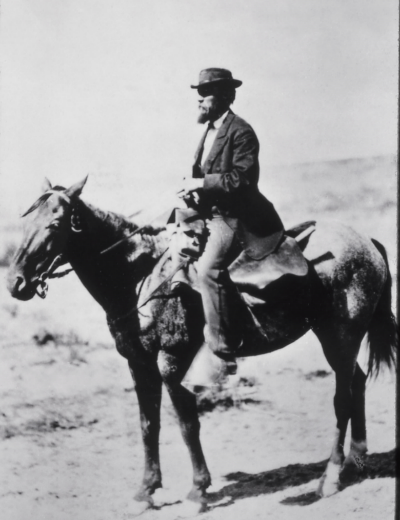

And, maybe there should be something else named Hayden in Idaho after a man the state has so far not honored. It was Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden (photo) who lead the famous Hayden Expedition to Yellowstone in 1871, which passed through Fort Hall on its way to what would become our nation’s first national park. The expedition named a lot of things, including Higham Peak in Bannock County, but nothing in Idaho bears the name of its leader.

The Hayden creek our reader asked about flows into Hayden Lake in Kootenai County and is not mentioned in Boones book. The lake and town are named after Mathew Hayden so it follows that the creek probably also carries his name. Hayden was reportedly (wait for it…) playing cards with John Hager at Hager’s cabin. There was no gunplay involved with this one. The two men agreed to name the lake after the winner of a seven-up game. Hayden won.

But wait! There’s more! We can’t forget Hayden Peak in Owyhee County. It was named after Everett Hayden, a surveyor working for the Smithsonian Institution in the 1880s. Reportedly there was some local grumbling at the time because Hayden had never even been near the peak.

And, maybe there should be something else named Hayden in Idaho after a man the state has so far not honored. It was Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden (photo) who lead the famous Hayden Expedition to Yellowstone in 1871, which passed through Fort Hall on its way to what would become our nation’s first national park. The expedition named a lot of things, including Higham Peak in Bannock County, but nothing in Idaho bears the name of its leader.

Published on July 08, 2023 04:00

July 7, 2023

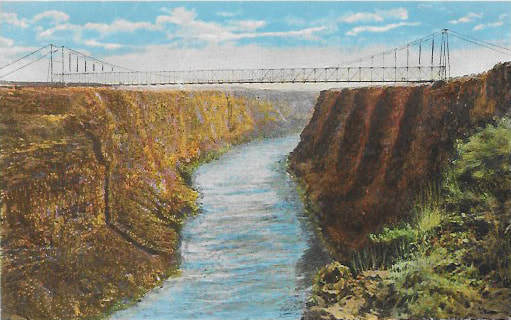

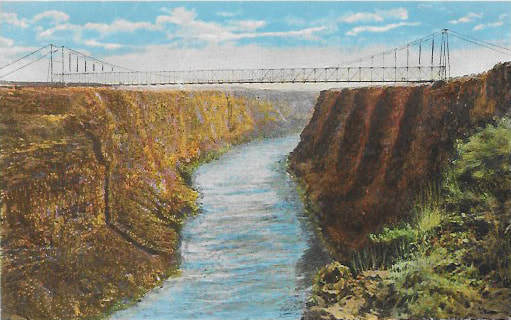

Crossing the Canyon

The Hansen Bridge, which spanned the Snake River Canyon near the town of Hansen, was a bit of a wonder in 1919 when it was built. It was 608 feet across, making it the second longest span in the country at the time. At 325 feet above the river, some accounts had it listed as being the highest suspension bridge in the world. And some accounts also listed it as being 345 feet above the Snake and 688 feet long. Break out your tape measure.

Superlatives aside, it held no record for width. At 16 feet, it seemed not to foresee a future where a couple of trucks might want to pass in opposite directions. The original wooden decking on the bridge also seemed better suited to wagons, whose use was waning, than automobiles.

Some locals may have been disappointed in the celebration for the bridge. Police seized 120 pints of booze one resident of Buhl was hoping to sell to the crowds when Gov. D.W. Davis officially opened the bridge.

The Hansen Bridge was important in its day, even if transportation needs quickly outgrew it. It remained in service until 1966.

Superlatives aside, it held no record for width. At 16 feet, it seemed not to foresee a future where a couple of trucks might want to pass in opposite directions. The original wooden decking on the bridge also seemed better suited to wagons, whose use was waning, than automobiles.

Some locals may have been disappointed in the celebration for the bridge. Police seized 120 pints of booze one resident of Buhl was hoping to sell to the crowds when Gov. D.W. Davis officially opened the bridge.

The Hansen Bridge was important in its day, even if transportation needs quickly outgrew it. It remained in service until 1966.

Published on July 07, 2023 04:00

July 6, 2023

Grover Cleveland Probably didn't Sleep here

One step over from history is persistent, salacious rumor. Such is the story of Frieda Bethmann, one-time resident of Pardee, Idaho.

A 1990 story in the Lewiston Tribune by Diane Pettit, which is easily found on the web, recounts the persistent rumors about Frieda and her son Miner. Frieda was the daughter of Francis Alfred Ferdinand Bethmann and Emile Bethmann. Her father was in the sugar importing business and her mother was active in the kindergarten movement.

The Bethmanns were friends with President Grover Cleveland. That Frieda turned up with a “nephew” named Miner who was almost certainly her son started the rumors rumbling. Cleveland admitted to fathering one illegitimate child in his bachelor days. Perhaps there was a second.

About 1908 after the death of her father, Frieda and her mother moved to a grand house overlooking the Clearwater River. Rumors had Pres. Cleveland building the house for his “mistress.” In fact, the house was built by Frieda’s mother. She purchased the land and oversaw its construction herself.

But it was Frieda everyone was interested in. Rumor had it that she had served as Cleveland’s appointment secretary, no doubt with emphasis on the “appointment.” In fact, she had served briefly as a kindergarten instructor to the Cleveland children.

The rumors had Cleveland making several visits to Idaho by rail. No photo or newspaper account seems to exist that would prove that. Cleveland allegedly signed the guest register at a Pomeroy, Washington hotel, but even that tenuous clue seems suspect as the signature looks nothing like Cleveland’s signature.

Miner Bethmann had reporters showing up on his doorstep from time to time throughout his life. He is said to have driven them off without comment.

The rumors persist and, yes, this retelling will only help keep them alive. We will probably never know who Miner’s father was. We do know that certain parts of the speculation, such as who built the house, are incorrect. Rumors about Cleveland visiting Frieda in Pardee seem not to add up. The Bethmanns moved there in 1908, the year Grover Cleveland died at age 71.

Pres. Cleveland may not have fathered a boy who grew up in Idaho, but he did do one thing that helped shape the state. In 1887 there was a movement in Congress to split off the northern part of Idaho Territory and attach it to Washington. The bill landed on President Cleveland’s desk, where it died as a pocket veto.

Thanks to Dick Southern for supplying much information on the Bethmanns in his exhaustive local book on Pardee, Idaho history They Called This Canyon “Home.”

The inset photo is of Emile Bethmann (left) and daughter Frieda. The larger photo is of Miner in front of the Bethmann home. They are part of Dick Southern’s collection.

The inset photo is of Emile Bethmann (left) and daughter Frieda. The larger photo is of Miner in front of the Bethmann home. They are part of Dick Southern’s collection.

A 1990 story in the Lewiston Tribune by Diane Pettit, which is easily found on the web, recounts the persistent rumors about Frieda and her son Miner. Frieda was the daughter of Francis Alfred Ferdinand Bethmann and Emile Bethmann. Her father was in the sugar importing business and her mother was active in the kindergarten movement.

The Bethmanns were friends with President Grover Cleveland. That Frieda turned up with a “nephew” named Miner who was almost certainly her son started the rumors rumbling. Cleveland admitted to fathering one illegitimate child in his bachelor days. Perhaps there was a second.

About 1908 after the death of her father, Frieda and her mother moved to a grand house overlooking the Clearwater River. Rumors had Pres. Cleveland building the house for his “mistress.” In fact, the house was built by Frieda’s mother. She purchased the land and oversaw its construction herself.

But it was Frieda everyone was interested in. Rumor had it that she had served as Cleveland’s appointment secretary, no doubt with emphasis on the “appointment.” In fact, she had served briefly as a kindergarten instructor to the Cleveland children.

The rumors had Cleveland making several visits to Idaho by rail. No photo or newspaper account seems to exist that would prove that. Cleveland allegedly signed the guest register at a Pomeroy, Washington hotel, but even that tenuous clue seems suspect as the signature looks nothing like Cleveland’s signature.

Miner Bethmann had reporters showing up on his doorstep from time to time throughout his life. He is said to have driven them off without comment.

The rumors persist and, yes, this retelling will only help keep them alive. We will probably never know who Miner’s father was. We do know that certain parts of the speculation, such as who built the house, are incorrect. Rumors about Cleveland visiting Frieda in Pardee seem not to add up. The Bethmanns moved there in 1908, the year Grover Cleveland died at age 71.

Pres. Cleveland may not have fathered a boy who grew up in Idaho, but he did do one thing that helped shape the state. In 1887 there was a movement in Congress to split off the northern part of Idaho Territory and attach it to Washington. The bill landed on President Cleveland’s desk, where it died as a pocket veto.

Thanks to Dick Southern for supplying much information on the Bethmanns in his exhaustive local book on Pardee, Idaho history They Called This Canyon “Home.”

The inset photo is of Emile Bethmann (left) and daughter Frieda. The larger photo is of Miner in front of the Bethmann home. They are part of Dick Southern’s collection.

The inset photo is of Emile Bethmann (left) and daughter Frieda. The larger photo is of Miner in front of the Bethmann home. They are part of Dick Southern’s collection.

Published on July 06, 2023 04:00

July 5, 2023

The Shape we're in

With so many new residents popping up, I thought it might be helpful for them to learn some basics about the state. I'd first like to help them learn to identify Idaho by its unique shape. Can you identify Idaho by its shape? Check your answer by scrolling down.

A E

E  B

B  F

F  C

C  G

G  D

D  H

H

Well, let's see how you did.

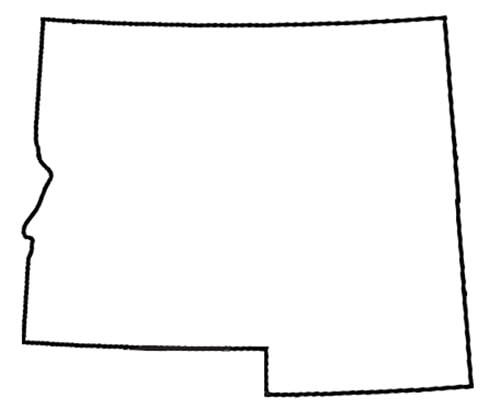

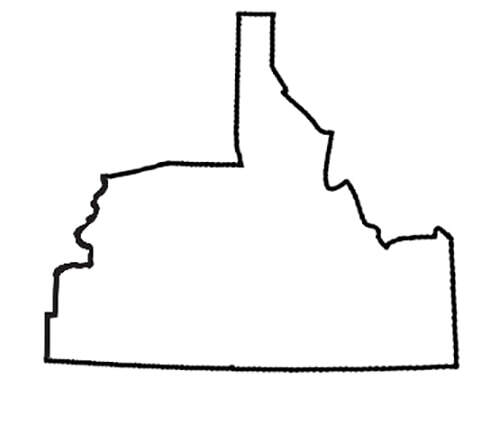

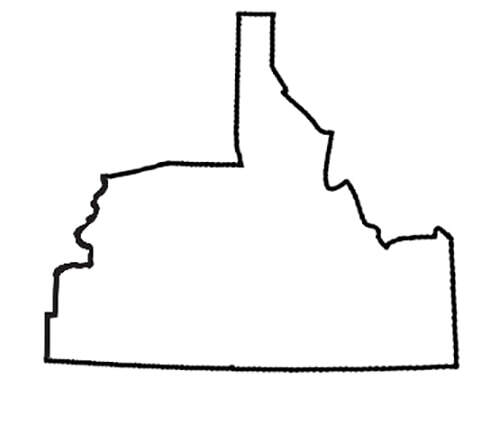

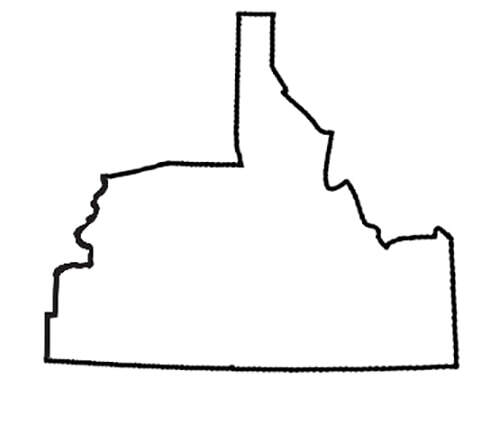

If you picked this one, check your calendar. If it’s 1863, then this one is correct. When President Abraham Lincoln signed the bill creating Idaho Territory on March 4, 1863, this is what it looked like. It included all of what would later become Montana and Wyoming. The territory was bigger than Texas and, for a few months, was the largest US Territory.

If you picked this one, check your calendar. If it’s 1863, then this one is correct. When President Abraham Lincoln signed the bill creating Idaho Territory on March 4, 1863, this is what it looked like. It included all of what would later become Montana and Wyoming. The territory was bigger than Texas and, for a few months, was the largest US Territory.  This was right, once. In 1864, Idaho Territory went on a serious diet. Congress wisely decided that one Texas was plenty, thank you very much. Northeast Idaho Territory became Montana Territory that year. At the same time, Idaho lost most of Wyoming.

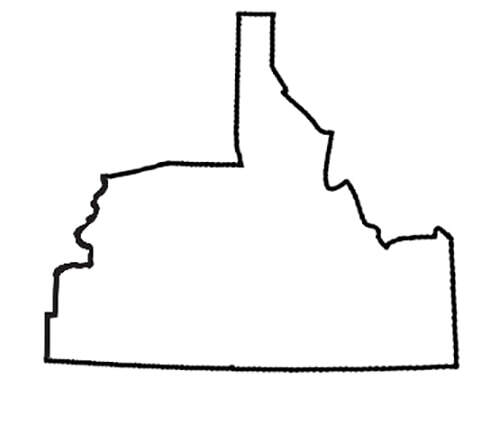

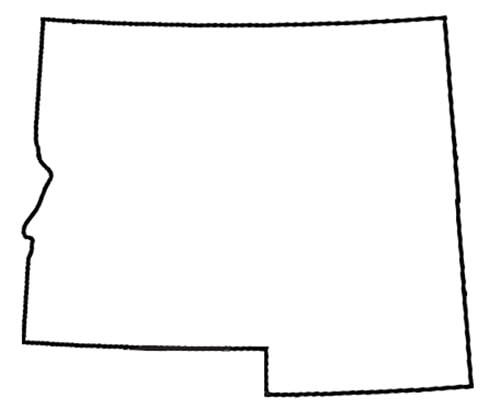

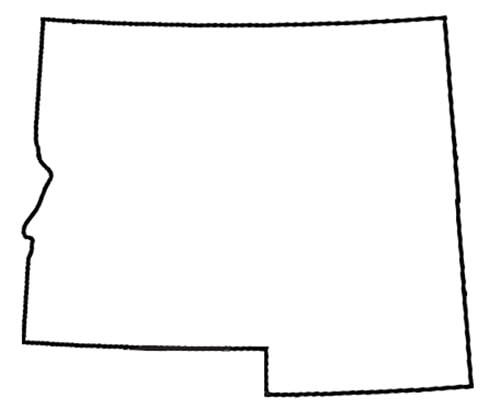

This was right, once. In 1864, Idaho Territory went on a serious diet. Congress wisely decided that one Texas was plenty, thank you very much. Northeast Idaho Territory became Montana Territory that year. At the same time, Idaho lost most of Wyoming.  Idaho Territory slimmed up again in 1868, losing the love handle on the east that would become part of Wyoming. This is what Idaho looks like today. Pat yourself on the back if you chose this one.

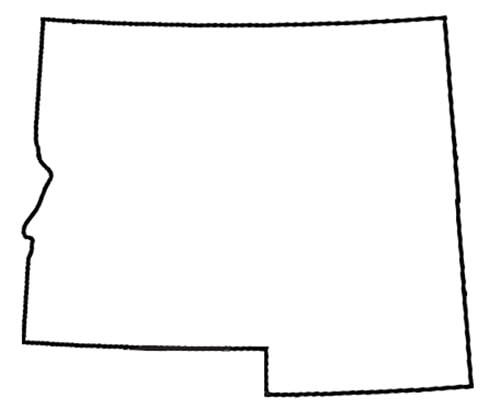

Idaho Territory slimmed up again in 1868, losing the love handle on the east that would become part of Wyoming. This is what Idaho looks like today. Pat yourself on the back if you chose this one.  This could be what Idaho looks like tomorrow if tomorrow is defined as “probably never.” When this book was written, there was something called the Greater Idaho Movement. Proponents, most of whom live in rural Oregon, so love Idaho’s scenic beauty that they just have to be a part of it. In writing circles, the preceding sentence is called a “lie.” Those secessionist Oregonians admire Idaho’s conservative politics and would love to thumb their collective noses at Salem, Oregon’s capital city, and the progressive politics in general on that side of the Cascades. Similar schemes to rejigger Idaho’s borders have popped up in the past. They have consistently failed because every state government involved in the proposal has to approve it, then Congress has to approve it.

This could be what Idaho looks like tomorrow if tomorrow is defined as “probably never.” When this book was written, there was something called the Greater Idaho Movement. Proponents, most of whom live in rural Oregon, so love Idaho’s scenic beauty that they just have to be a part of it. In writing circles, the preceding sentence is called a “lie.” Those secessionist Oregonians admire Idaho’s conservative politics and would love to thumb their collective noses at Salem, Oregon’s capital city, and the progressive politics in general on that side of the Cascades. Similar schemes to rejigger Idaho’s borders have popped up in the past. They have consistently failed because every state government involved in the proposal has to approve it, then Congress has to approve it.  If you chose this as the shape of Idaho, you are geographically challenged, but you are not alone. This is Iowa. One would think Iowa would change its name since three of the letters it contains are currently in use by Idaho. Some wags might point out that Iowa had those letters first, which is technically correct. Idaho, indisputably, wears them better. Iowa, you should consider Cornucopia, a lovely name implying abundance.

If you chose this as the shape of Idaho, you are geographically challenged, but you are not alone. This is Iowa. One would think Iowa would change its name since three of the letters it contains are currently in use by Idaho. Some wags might point out that Iowa had those letters first, which is technically correct. Idaho, indisputably, wears them better. Iowa, you should consider Cornucopia, a lovely name implying abundance.  Please say you didn’t choose this one. That’s Ohio. It, too, shares three letters with the State of Idaho. Frankly, we’re getting a little tired of that. See above. Pick your own dang name.

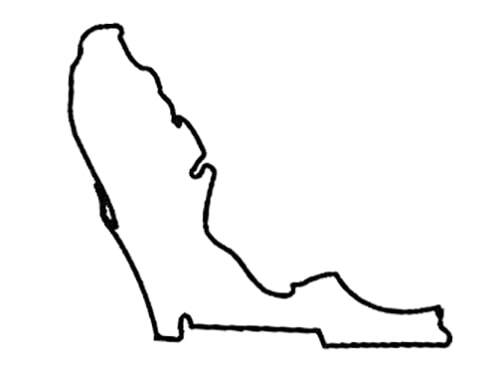

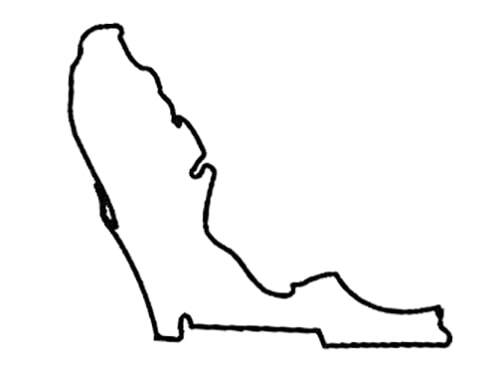

Please say you didn’t choose this one. That’s Ohio. It, too, shares three letters with the State of Idaho. Frankly, we’re getting a little tired of that. See above. Pick your own dang name.  You could almost be forgiven for picking this shape. Montana is practically begging to stick its nose in this upside-down image of Florida.

You could almost be forgiven for picking this shape. Montana is practically begging to stick its nose in this upside-down image of Florida.

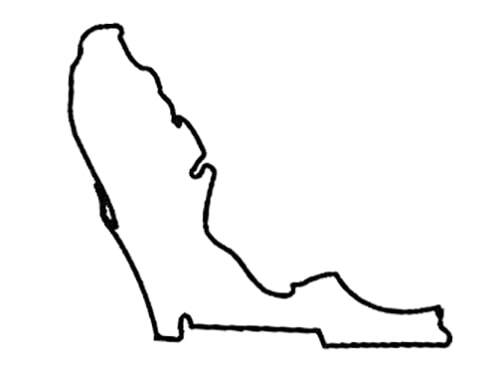

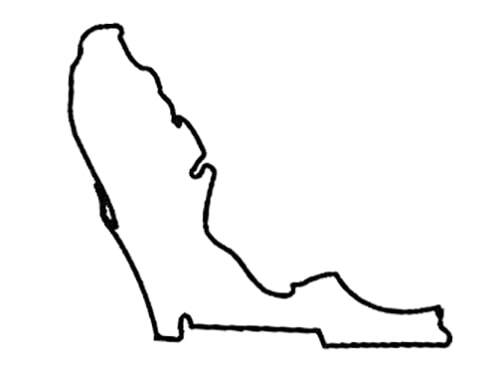

If you chose this map, you may be from Mayberry. An upside-down map of Idaho hung on the wall of the sheriff’s office in some of the old Andy Griffith shows on TV. It may have been meant to be the outline of the fictional town of Mayberry or the fictional county it was in. A map of Nevada got the same treatment in at least one episode. The map used most often for the background in those office scenes was one of Cincinnati.

If you chose this map, you may be from Mayberry. An upside-down map of Idaho hung on the wall of the sheriff’s office in some of the old Andy Griffith shows on TV. It may have been meant to be the outline of the fictional town of Mayberry or the fictional county it was in. A map of Nevada got the same treatment in at least one episode. The map used most often for the background in those office scenes was one of Cincinnati.

A

E

E  B

B  F

F  C

C  G

G  D

D  H

H

Well, let's see how you did.

If you picked this one, check your calendar. If it’s 1863, then this one is correct. When President Abraham Lincoln signed the bill creating Idaho Territory on March 4, 1863, this is what it looked like. It included all of what would later become Montana and Wyoming. The territory was bigger than Texas and, for a few months, was the largest US Territory.

If you picked this one, check your calendar. If it’s 1863, then this one is correct. When President Abraham Lincoln signed the bill creating Idaho Territory on March 4, 1863, this is what it looked like. It included all of what would later become Montana and Wyoming. The territory was bigger than Texas and, for a few months, was the largest US Territory.  This was right, once. In 1864, Idaho Territory went on a serious diet. Congress wisely decided that one Texas was plenty, thank you very much. Northeast Idaho Territory became Montana Territory that year. At the same time, Idaho lost most of Wyoming.

This was right, once. In 1864, Idaho Territory went on a serious diet. Congress wisely decided that one Texas was plenty, thank you very much. Northeast Idaho Territory became Montana Territory that year. At the same time, Idaho lost most of Wyoming.  Idaho Territory slimmed up again in 1868, losing the love handle on the east that would become part of Wyoming. This is what Idaho looks like today. Pat yourself on the back if you chose this one.

Idaho Territory slimmed up again in 1868, losing the love handle on the east that would become part of Wyoming. This is what Idaho looks like today. Pat yourself on the back if you chose this one.  This could be what Idaho looks like tomorrow if tomorrow is defined as “probably never.” When this book was written, there was something called the Greater Idaho Movement. Proponents, most of whom live in rural Oregon, so love Idaho’s scenic beauty that they just have to be a part of it. In writing circles, the preceding sentence is called a “lie.” Those secessionist Oregonians admire Idaho’s conservative politics and would love to thumb their collective noses at Salem, Oregon’s capital city, and the progressive politics in general on that side of the Cascades. Similar schemes to rejigger Idaho’s borders have popped up in the past. They have consistently failed because every state government involved in the proposal has to approve it, then Congress has to approve it.

This could be what Idaho looks like tomorrow if tomorrow is defined as “probably never.” When this book was written, there was something called the Greater Idaho Movement. Proponents, most of whom live in rural Oregon, so love Idaho’s scenic beauty that they just have to be a part of it. In writing circles, the preceding sentence is called a “lie.” Those secessionist Oregonians admire Idaho’s conservative politics and would love to thumb their collective noses at Salem, Oregon’s capital city, and the progressive politics in general on that side of the Cascades. Similar schemes to rejigger Idaho’s borders have popped up in the past. They have consistently failed because every state government involved in the proposal has to approve it, then Congress has to approve it.  If you chose this as the shape of Idaho, you are geographically challenged, but you are not alone. This is Iowa. One would think Iowa would change its name since three of the letters it contains are currently in use by Idaho. Some wags might point out that Iowa had those letters first, which is technically correct. Idaho, indisputably, wears them better. Iowa, you should consider Cornucopia, a lovely name implying abundance.

If you chose this as the shape of Idaho, you are geographically challenged, but you are not alone. This is Iowa. One would think Iowa would change its name since three of the letters it contains are currently in use by Idaho. Some wags might point out that Iowa had those letters first, which is technically correct. Idaho, indisputably, wears them better. Iowa, you should consider Cornucopia, a lovely name implying abundance.  Please say you didn’t choose this one. That’s Ohio. It, too, shares three letters with the State of Idaho. Frankly, we’re getting a little tired of that. See above. Pick your own dang name.

Please say you didn’t choose this one. That’s Ohio. It, too, shares three letters with the State of Idaho. Frankly, we’re getting a little tired of that. See above. Pick your own dang name.  You could almost be forgiven for picking this shape. Montana is practically begging to stick its nose in this upside-down image of Florida.

You could almost be forgiven for picking this shape. Montana is practically begging to stick its nose in this upside-down image of Florida. If you chose this map, you may be from Mayberry. An upside-down map of Idaho hung on the wall of the sheriff’s office in some of the old Andy Griffith shows on TV. It may have been meant to be the outline of the fictional town of Mayberry or the fictional county it was in. A map of Nevada got the same treatment in at least one episode. The map used most often for the background in those office scenes was one of Cincinnati.

If you chose this map, you may be from Mayberry. An upside-down map of Idaho hung on the wall of the sheriff’s office in some of the old Andy Griffith shows on TV. It may have been meant to be the outline of the fictional town of Mayberry or the fictional county it was in. A map of Nevada got the same treatment in at least one episode. The map used most often for the background in those office scenes was one of Cincinnati.

Published on July 05, 2023 04:00

July 4, 2023

Those Phantom Chinese Tunnels

I enter the Chinese tunnels of Boise with some trepidation, knowing that opinions are strong and documentation is weak. Actually, let’s say I enter the debate, since the tunnels themselves are so elusive.

There were many newspaper mentions of tunnels built by Chinese laborers in the late 1800s. They weren’t in Boise, though. The stories that mentioned the tunnels were about mining in the mountains.

Boise had a substantial Chinese population in the late 1800s and early 1900s, but did they build tunnels? If they didn’t, where did the myth come from? There were Chinese tunnels, most famously in San Francisco. Portland had a network called the Shanghai tunnels. Los Angeles had Chinese tunnels. Did Boise?

I searched for mention of them in digital scans of the Statesman from those years and turned up nothing. The first mention I found of Chinese tunnels in the Statesman was in a column by Dick d’Easum in 1961. He was addressing the “myth” of the tunnels and speculating on how it got started. There were underground rooms that led off basements in the Chinese section of the city. It was said that illicit activities sometimes occurred there, such as the smoking of opium. What did not seem to be the case was that those rooms connected in a network beneath the city that would allow someone to enter at one point and pop up blocks away.

One possible source of the tunnel stories was the prevalence of unauthorized sewers. Today we hear of sinkholes opening up and swallowing cars. In Boise in the 1880s such sinkholes could make horses disappear. Dick d’Easum told of a wagon loaded with merchandise that suddenly sank half out of sight on Idaho Street. The struggling team of horses were soon pulled into the widening hole. A Chinese sewer was the cause. Once the team and wagon were extricated it was filled in. The city engineer found more unauthorized sewers and the city council decreed that they all be filled in.

Over the years Boise has had countless street and utility projects, not to mention the construction, deconstruction, and reconstruction of numerous buildings. No Chinese tunnels have been found. Yet, the myth persists. That’s partly because one can’t prove a negative such as this. There MIGHT be a system of tunnels somewhere that have yet to be found. Dig deeper, maybe. Great Uncle Hyrum said he saw them.

By the way, the graphic is supposed to be “China Tunnel” in pinyin, if you can trust those internet translation services.

There were many newspaper mentions of tunnels built by Chinese laborers in the late 1800s. They weren’t in Boise, though. The stories that mentioned the tunnels were about mining in the mountains.

Boise had a substantial Chinese population in the late 1800s and early 1900s, but did they build tunnels? If they didn’t, where did the myth come from? There were Chinese tunnels, most famously in San Francisco. Portland had a network called the Shanghai tunnels. Los Angeles had Chinese tunnels. Did Boise?

I searched for mention of them in digital scans of the Statesman from those years and turned up nothing. The first mention I found of Chinese tunnels in the Statesman was in a column by Dick d’Easum in 1961. He was addressing the “myth” of the tunnels and speculating on how it got started. There were underground rooms that led off basements in the Chinese section of the city. It was said that illicit activities sometimes occurred there, such as the smoking of opium. What did not seem to be the case was that those rooms connected in a network beneath the city that would allow someone to enter at one point and pop up blocks away.

One possible source of the tunnel stories was the prevalence of unauthorized sewers. Today we hear of sinkholes opening up and swallowing cars. In Boise in the 1880s such sinkholes could make horses disappear. Dick d’Easum told of a wagon loaded with merchandise that suddenly sank half out of sight on Idaho Street. The struggling team of horses were soon pulled into the widening hole. A Chinese sewer was the cause. Once the team and wagon were extricated it was filled in. The city engineer found more unauthorized sewers and the city council decreed that they all be filled in.

Over the years Boise has had countless street and utility projects, not to mention the construction, deconstruction, and reconstruction of numerous buildings. No Chinese tunnels have been found. Yet, the myth persists. That’s partly because one can’t prove a negative such as this. There MIGHT be a system of tunnels somewhere that have yet to be found. Dig deeper, maybe. Great Uncle Hyrum said he saw them.

By the way, the graphic is supposed to be “China Tunnel” in pinyin, if you can trust those internet translation services.

Published on July 04, 2023 04:00

July 3, 2023

Pulaski was the Hero of the Big Burn

The Great Fire of 1910, often called the Big Burn, was one of the seminal events in Idaho history, and changed the way foresters thought about fire.

I’ll give you a brief outline today. For the complete story I recommend The Big Burn, by Timothy Egan.

The fire burned over two days, August 21 and 22 of 1910, incinerating 3 million acres in Washington, Montana, British Columbia, and Idaho. Even though fires have been growing in size in recent years, it remains the largest forest fire in the United States.

By mid-August that year there were more than a thousand fires burning in the drought-stricken Pacific Northwest. They started from a variety of sources including cinders from locomotives, campfires gone rogue, and lightening. Bad as that was, the multiple fires would become one big monster on August 20, when hurricane force winds blew through the region.

The Big Burn killed 87 people. To their peril, firefighters tried to stop it. An entire crew of 28 men lost their lives near Avery. In all, 78 firefighters perished. In desperation forest ranger Ed Pulaski led his 45-man crew into an abandoned mine tunnel to escape the flames. It was so hot and smoky in there that several men tried to go back outside. Pulaski pulled his gun on them to force them to stay. Five died in the tunnel, but the rest survived. The old War Eagle mine tunnel, south of Wallace, is now known as the Pulaski Tunnel, and is on the National Register of Historic Places. About a third of the town of Wallace was destroyed by the fire. The 1910 Fire made Ed Pulaski a hero. His name lives on for his courage and also for the firefighting tool he invented. The Pulaski has an axe head with a grubbing head on the other side.

The 1910 Fire made Ed Pulaski a hero. His name lives on for his courage and also for the firefighting tool he invented. The Pulaski has an axe head with a grubbing head on the other side.  The mouth of the old mine where Pulaski sheltered his men during the Big Burn. The tunnel is 60 feet long.

The mouth of the old mine where Pulaski sheltered his men during the Big Burn. The tunnel is 60 feet long.

I’ll give you a brief outline today. For the complete story I recommend The Big Burn, by Timothy Egan.

The fire burned over two days, August 21 and 22 of 1910, incinerating 3 million acres in Washington, Montana, British Columbia, and Idaho. Even though fires have been growing in size in recent years, it remains the largest forest fire in the United States.

By mid-August that year there were more than a thousand fires burning in the drought-stricken Pacific Northwest. They started from a variety of sources including cinders from locomotives, campfires gone rogue, and lightening. Bad as that was, the multiple fires would become one big monster on August 20, when hurricane force winds blew through the region.

The Big Burn killed 87 people. To their peril, firefighters tried to stop it. An entire crew of 28 men lost their lives near Avery. In all, 78 firefighters perished. In desperation forest ranger Ed Pulaski led his 45-man crew into an abandoned mine tunnel to escape the flames. It was so hot and smoky in there that several men tried to go back outside. Pulaski pulled his gun on them to force them to stay. Five died in the tunnel, but the rest survived. The old War Eagle mine tunnel, south of Wallace, is now known as the Pulaski Tunnel, and is on the National Register of Historic Places. About a third of the town of Wallace was destroyed by the fire.

The 1910 Fire made Ed Pulaski a hero. His name lives on for his courage and also for the firefighting tool he invented. The Pulaski has an axe head with a grubbing head on the other side.

The 1910 Fire made Ed Pulaski a hero. His name lives on for his courage and also for the firefighting tool he invented. The Pulaski has an axe head with a grubbing head on the other side.  The mouth of the old mine where Pulaski sheltered his men during the Big Burn. The tunnel is 60 feet long.

The mouth of the old mine where Pulaski sheltered his men during the Big Burn. The tunnel is 60 feet long.

Published on July 03, 2023 04:00

July 2, 2023

She Wanted Asphalt with Her Chicken Dinner

Chicken dinner. Yum. It was yummy enough to get a road paved once in Canyon County.

The story about how Chicken Dinner Road got its name appeared in the Idaho Press Tribune in about 1992, and was reprinted in 2008. It seems that Morris and Laura Lamb were friends of Governor C. Ben Ross and his wife Edna. They had eaten dinner together many times at the Lamb home.

One day, in the 1930s, Mrs. Lamb, who was noted for her chicken, rolls, and apple pie meals, was in Boise. She invited the governor to come to dinner. During the same conversation, she complained to Ross about the pitiful condition of the road in front of their place, which was dirt pocked with potholes. Ross was purported to say something like, “Laura, if you get that road graded and graveled, I’ll see to it it’s oiled.

Mrs. Lamb approached the Canyon County Commissioners who saw that opportunity as a fine one. They graded and graveled the road. As soon as that was done, she was on the phone to the governor reminding him of his promise. The next day—this part seems unlikely, but it’s Mrs. Lamb’s story—the next day the road was oiled.

The story got around and local hooligans thought it would be droll to put up a big hand-scrawled sign in front of the Lamb house in the dark of night. It read “Lamb’s Chicken Dinner Avenue.” Mrs. Lamb was not amused. Still, the name stuck as Chicken Dinner Road.

Idaho Press Tribune writer Dave Wilkins penned the original story.

The story about how Chicken Dinner Road got its name appeared in the Idaho Press Tribune in about 1992, and was reprinted in 2008. It seems that Morris and Laura Lamb were friends of Governor C. Ben Ross and his wife Edna. They had eaten dinner together many times at the Lamb home.

One day, in the 1930s, Mrs. Lamb, who was noted for her chicken, rolls, and apple pie meals, was in Boise. She invited the governor to come to dinner. During the same conversation, she complained to Ross about the pitiful condition of the road in front of their place, which was dirt pocked with potholes. Ross was purported to say something like, “Laura, if you get that road graded and graveled, I’ll see to it it’s oiled.

Mrs. Lamb approached the Canyon County Commissioners who saw that opportunity as a fine one. They graded and graveled the road. As soon as that was done, she was on the phone to the governor reminding him of his promise. The next day—this part seems unlikely, but it’s Mrs. Lamb’s story—the next day the road was oiled.

The story got around and local hooligans thought it would be droll to put up a big hand-scrawled sign in front of the Lamb house in the dark of night. It read “Lamb’s Chicken Dinner Avenue.” Mrs. Lamb was not amused. Still, the name stuck as Chicken Dinner Road.

Idaho Press Tribune writer Dave Wilkins penned the original story.

Published on July 02, 2023 04:00

July 1, 2023

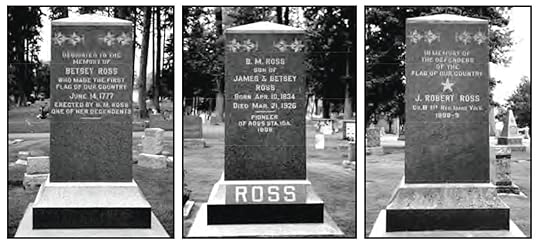

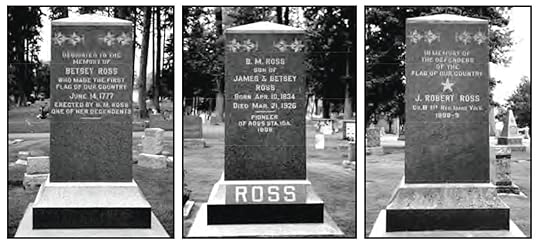

Honoring Betsey Ross in an Idaho Cemetery

Not all that is written in stone is true. I did a post earlier about a monument memorializing a (probably) nonexistent massacre near Almo. We can trace the roots of that one and get at least an inkling of why the memorial exists. Not so with the memorial to Betsey Ross in the Forest Memorial Cemetery in Coeur d’Alene.

Yes, it is apparently supposed to honor the woman of flag-making legend, although her name did not have that extra E. She died in Philadelphia in 1836. This memorial doesn’t say she’s buried in Coeur d’Alene, just that she is being honored by one of her descendants, B.M. Ross. On one side of the monument B.M. Ross is listed as the son of James and Betsey Ross, born in 1834. Interesting, in that Betsy Ross would have been 82 in 1834, two years before she died. Also, she had seven daughters and no sons.

The Coeur d’Alene Parks Department, which manages the cemeteries in the city, has done an excellent walking tour brochure about the history buried (sorry) in the cemetery. That’s where I found most of the information for this post. If you know anything about Betsey Ross or B.M. Ross, they’d love to hear about it. Clearly someone spent quite a bit of money to put up the monument. The question is, why?

Yes, it is apparently supposed to honor the woman of flag-making legend, although her name did not have that extra E. She died in Philadelphia in 1836. This memorial doesn’t say she’s buried in Coeur d’Alene, just that she is being honored by one of her descendants, B.M. Ross. On one side of the monument B.M. Ross is listed as the son of James and Betsey Ross, born in 1834. Interesting, in that Betsy Ross would have been 82 in 1834, two years before she died. Also, she had seven daughters and no sons.

The Coeur d’Alene Parks Department, which manages the cemeteries in the city, has done an excellent walking tour brochure about the history buried (sorry) in the cemetery. That’s where I found most of the information for this post. If you know anything about Betsey Ross or B.M. Ross, they’d love to hear about it. Clearly someone spent quite a bit of money to put up the monument. The question is, why?

Published on July 01, 2023 04:00