Rick Just's Blog, page 57

June 9, 2023

"The Dogcatcher is Abroad in this City"

Today’s post is about dogcatchers in Idaho history. It’s not a subject that gets a lot of attention, and this post will largely continue that tradition. I just did a word search through a couple of Idaho newspaper databases to see if anything interesting might come up.

I have more dogs than are strictly necessary (three). I keep them on leash, pick up after them, license them regularly, etc. So, this notice in the Idaho Statesman from June 10, 1911 caught my eye. It was datelined Nampa. “The dogcatcher is abroad in this city and acting under the mandates of the city council, urged to duty by the mayor and supported by the police department, a special officer has been detailed to enforce the law relative to taxation on dogs. The tax price is $3.50 for male and $5 for female dogs and any dog not wearing the tax collar will be summarily dispatched to happy hunting grounds after a short campaign in which each dog owner will have opportunity to pay up.”

This was apparently written in the days when it cost extra to insert an occasional period in a news story.

Several Idaho papers, including the Elmore Bulletin, carried a story about dogcatchers in Chicago in 1893. The short version is that they chased this big dog all over the city before finally capturing him and determining that he was a wolf.

The Wood River Times had a short opinion related to dogs and those who ought to catch them: “There are too many dogs in town for the public good. They annoy horsemen, teams and especially ladies on horseback, create disturbance with every strange dog visiting the town, keep peaceable people awake of nights, infest restaurants and public places, and are an intolerable nuisance. The dog-catchers should be started out.”

Stories about dogcatchers were often played for humor. In 1934 the Statesman ran the headline “Boise Mutts Yap Joyfully As Council Cans Dogcatcher.” It was a temporary budget move.

There were about as many stories intimating that someone couldn’t get elected dogcatcher as there were legitimate stories about dogcatchers. So, they may be able to catch dogs, but one thing dogcatchers can’t catch is a break.

I have more dogs than are strictly necessary (three). I keep them on leash, pick up after them, license them regularly, etc. So, this notice in the Idaho Statesman from June 10, 1911 caught my eye. It was datelined Nampa. “The dogcatcher is abroad in this city and acting under the mandates of the city council, urged to duty by the mayor and supported by the police department, a special officer has been detailed to enforce the law relative to taxation on dogs. The tax price is $3.50 for male and $5 for female dogs and any dog not wearing the tax collar will be summarily dispatched to happy hunting grounds after a short campaign in which each dog owner will have opportunity to pay up.”

This was apparently written in the days when it cost extra to insert an occasional period in a news story.

Several Idaho papers, including the Elmore Bulletin, carried a story about dogcatchers in Chicago in 1893. The short version is that they chased this big dog all over the city before finally capturing him and determining that he was a wolf.

The Wood River Times had a short opinion related to dogs and those who ought to catch them: “There are too many dogs in town for the public good. They annoy horsemen, teams and especially ladies on horseback, create disturbance with every strange dog visiting the town, keep peaceable people awake of nights, infest restaurants and public places, and are an intolerable nuisance. The dog-catchers should be started out.”

Stories about dogcatchers were often played for humor. In 1934 the Statesman ran the headline “Boise Mutts Yap Joyfully As Council Cans Dogcatcher.” It was a temporary budget move.

There were about as many stories intimating that someone couldn’t get elected dogcatcher as there were legitimate stories about dogcatchers. So, they may be able to catch dogs, but one thing dogcatchers can’t catch is a break.

Published on June 09, 2023 04:00

June 8, 2023

Idaho History: The Original Bingham County Courthouse

We’ve all had that feeling. The, “wait, it couldn’t have been that long ago” feeling. I get that sense when I drive by Courthouse Square in Blackfoot. It's a nice little park with a fountain that local delinquents enjoy pouring soap into on a regular basis.

But it wasn’t always a park. It was the site of the Bingham County Courthouse (picture), built in 1885. It was remodeled in 1956, which was about the time I would have started riding down Shilling Avenue past it with my mother, the “egg lady,” on her delivery rounds. I started driving past it myself in 1964 when I got my first driver’s license there at age 14.

The two-story building was something of an Italianate style with its bracketed eaves, segmental window arches, and cubical massing, all resting on a lava rock foundation. It served the needs of Bingham County for about a hundred years. The building was demolished in 1987. A new courthouse was built across town.

Shilling Avenue in Blackfoot is named after early pioneer Watson N. Shilling. He was instrumental in securing the authority for the railroad to cross the Fort Hall Indian Reservation in 1878.

This post uses information from a booklet called “The Historic Shilling District” published by the Bingham County Historical Society.

But it wasn’t always a park. It was the site of the Bingham County Courthouse (picture), built in 1885. It was remodeled in 1956, which was about the time I would have started riding down Shilling Avenue past it with my mother, the “egg lady,” on her delivery rounds. I started driving past it myself in 1964 when I got my first driver’s license there at age 14.

The two-story building was something of an Italianate style with its bracketed eaves, segmental window arches, and cubical massing, all resting on a lava rock foundation. It served the needs of Bingham County for about a hundred years. The building was demolished in 1987. A new courthouse was built across town.

Shilling Avenue in Blackfoot is named after early pioneer Watson N. Shilling. He was instrumental in securing the authority for the railroad to cross the Fort Hall Indian Reservation in 1878.

This post uses information from a booklet called “The Historic Shilling District” published by the Bingham County Historical Society.

Published on June 08, 2023 04:00

June 7, 2023

Boise's Mikado Steam Engine

One of the most common locomotive engines during the heyday of steam was the Mikado. It was called the Mikado because many of the first engines were built for export to Japan. Railroad workers nicknamed the Mikados “Mike.” That’s why the one on display at the Boise Depot is called Big Mike.

They were giants. Big Mike is almost 82 feet long, counting its tender. It’s 15 feet 10 3/8 inches from the ground to the top of the stack, and the whole thing weighs 463,000 pounds before it takes on up to 17 tons of coal and 10,000 gallons of water.

They built the 14,000 Mikados from 1911 through 1944. Big Mike is a Mikado 282, which means it has eight big wheels underneath the locomotive with two smaller wheels in front and two in back.

Big Mike, or Engine No. 2295, was retired by Union Pacific and donated to the city of Boise in 1956. The locomotive was subsequently moved to the 3rd Street entrance to Julia Davis Park.

On Dec. 9, 2007, Big Mike—minus its tender—was moved to a new home on a siding east of the Boise Depot. Hundreds of people watched the move, which occurred at midnight on a cold winter's night. The tender, which carried water and fuel for the engine, was separated from the engine and had been moved on Dec. 6, 2007.

It’s well worth visiting the Boise Depot and Big Mike if you haven’t already done so.

They were giants. Big Mike is almost 82 feet long, counting its tender. It’s 15 feet 10 3/8 inches from the ground to the top of the stack, and the whole thing weighs 463,000 pounds before it takes on up to 17 tons of coal and 10,000 gallons of water.

They built the 14,000 Mikados from 1911 through 1944. Big Mike is a Mikado 282, which means it has eight big wheels underneath the locomotive with two smaller wheels in front and two in back.

Big Mike, or Engine No. 2295, was retired by Union Pacific and donated to the city of Boise in 1956. The locomotive was subsequently moved to the 3rd Street entrance to Julia Davis Park.

On Dec. 9, 2007, Big Mike—minus its tender—was moved to a new home on a siding east of the Boise Depot. Hundreds of people watched the move, which occurred at midnight on a cold winter's night. The tender, which carried water and fuel for the engine, was separated from the engine and had been moved on Dec. 6, 2007.

It’s well worth visiting the Boise Depot and Big Mike if you haven’t already done so.

Published on June 07, 2023 04:00

June 6, 2023

Boise History: The 1967 Airport Bond

NOTE: This post was written by Tommy Dickey. Tommy was my spring intern from the Boise State University Department of History. He assisted me in researching stories for my blog.

By Tommy Dickey

Boise’s first airport was built in 1926, where Boise State University is today. The city began purchasing land at the current location in 1936. By 1938, it boasted the world’s longest runway at 8,000 feet.

In 1961 the number of enplaned passengers was 86,000. That number reached 148,000 by 1966.

The City of Boise ran a general obligation bond election in 1967 to enlarge and remodel the airport terminal, providing better passenger services and more access for automobiles and parking. Don Duvall and the five-man Airport Commission advocated for the bond by speaking at forums to businessmen, ladies’ luncheons, and late-evening community gatherings. The bond issue passed with an overwhelming 75 percent voting in favor. It cost roughly $1.5 million.

The Boise airport has continued to adapt. The terminal has undergone several major remodels since the 1967 vote. In 2022 the Boise Airport reached almost 4.5 million passengers and is currently home to eight airlines.

Map from a 1967 brochure showing "Boise's Strategic Location."

Map from a 1967 brochure showing "Boise's Strategic Location."

By Tommy Dickey

Boise’s first airport was built in 1926, where Boise State University is today. The city began purchasing land at the current location in 1936. By 1938, it boasted the world’s longest runway at 8,000 feet.

In 1961 the number of enplaned passengers was 86,000. That number reached 148,000 by 1966.

The City of Boise ran a general obligation bond election in 1967 to enlarge and remodel the airport terminal, providing better passenger services and more access for automobiles and parking. Don Duvall and the five-man Airport Commission advocated for the bond by speaking at forums to businessmen, ladies’ luncheons, and late-evening community gatherings. The bond issue passed with an overwhelming 75 percent voting in favor. It cost roughly $1.5 million.

The Boise airport has continued to adapt. The terminal has undergone several major remodels since the 1967 vote. In 2022 the Boise Airport reached almost 4.5 million passengers and is currently home to eight airlines.

Map from a 1967 brochure showing "Boise's Strategic Location."

Map from a 1967 brochure showing "Boise's Strategic Location."

Published on June 06, 2023 04:00

June 5, 2023

Idaho History: Kitchen Matches, Gooseberries, and the White Pine

Today's post is about an Idaho state symbol that is so useful you probably have one of its products in your kitchen cupboard right now. The western white pine is an important tree for the timber industry. It's a durable, close-grained tree that is uniform in texture.

White pine is lightweight, seasons without warping takes nails without splitting, and saws easily. That makes it a terrific tree for door and window frames, cabinets, and paneling. Oh yes, about the white pine that's in your cupboard right now--kitchen matches.

The western white pine does best in a cool and dry climate. Although it can grow at sea level, it prefers elevations of 2500 to 6000 feet. In Idaho, it grows mostly in the panhandle. A mature tree typically gets to be about 100 feet high.

A gregarious tree, the western white pine seems to prefer mixing with other common evergreens rather than in large stands of its own. One plant it would be better off not mixing with is the currant. A fungus called pine blister rust kills the pine, but it's only found where currants or gooseberries also grow.

The western white pine was named the state tree of Idaho by the 1935 legislature

The photo below is on display at the Museum of Northern Idaho in Coeur d’Alene. It’s labeled as the “Largest Known White Pine.” How large? It was 207 feet tall, and its diameter was 6 feet 7 inches. It scaled at 29,800 board feet measure. The rings counted out at 425, so it was 425 years old when cut down in 1912. The live tree was located seven miles northwest of Bovill.

White pine is lightweight, seasons without warping takes nails without splitting, and saws easily. That makes it a terrific tree for door and window frames, cabinets, and paneling. Oh yes, about the white pine that's in your cupboard right now--kitchen matches.

The western white pine does best in a cool and dry climate. Although it can grow at sea level, it prefers elevations of 2500 to 6000 feet. In Idaho, it grows mostly in the panhandle. A mature tree typically gets to be about 100 feet high.

A gregarious tree, the western white pine seems to prefer mixing with other common evergreens rather than in large stands of its own. One plant it would be better off not mixing with is the currant. A fungus called pine blister rust kills the pine, but it's only found where currants or gooseberries also grow.

The western white pine was named the state tree of Idaho by the 1935 legislature

The photo below is on display at the Museum of Northern Idaho in Coeur d’Alene. It’s labeled as the “Largest Known White Pine.” How large? It was 207 feet tall, and its diameter was 6 feet 7 inches. It scaled at 29,800 board feet measure. The rings counted out at 425, so it was 425 years old when cut down in 1912. The live tree was located seven miles northwest of Bovill.

Published on June 05, 2023 04:00

June 4, 2023

Idaho History: The Bones of the Tyee

Logging was THE industry around Priest Lake in the latter part of the 19th century and much of the 20th. Diamond Match Company cut a lot of Western white pine around the lake so that people all around the world could strike a match.

There is still some evidence of old logging operations around the lake if you know where to look. In the Indian Creek Unit of Priest Lake State Park—the first unit on the lake you’ll come to—you’ll find a replica of a logging flume. You’ll find it on your own, right on the edge of the campground. But if you want to see the real remains of a logging flume and the remains of the old wooden dam that diverted water into the flume to float the logs, ask a ranger. There’s a road up the hillside not far away that will take you there (on foot), if you’re adventurous.

Once you’ve seen that, drive north to the Lionhead Group Camp. You’ll see some old dormitory buildings and a shower building near the white sand beach. Those buildings, which are still used today, were once part of a floating timber camp. The camp floated so they could move it around the lake to where the current cut was taking place.

Now, head up the road a mile or so to the Lionhead boat ramp. Park there and take a look at the relic of the Tyee II, sunk in the little bay, creating a picturesque scene. The Tyee II was the last wood-burning steam tugboat on the lake. It pulled a lot of logs in its day. The picture on top shows it circa 1930, while the color picture is a snap of the old hulk resting in the sand.

By the way, Tyee means chief or boss. It also refers to a large Chinook salmon.

There is still some evidence of old logging operations around the lake if you know where to look. In the Indian Creek Unit of Priest Lake State Park—the first unit on the lake you’ll come to—you’ll find a replica of a logging flume. You’ll find it on your own, right on the edge of the campground. But if you want to see the real remains of a logging flume and the remains of the old wooden dam that diverted water into the flume to float the logs, ask a ranger. There’s a road up the hillside not far away that will take you there (on foot), if you’re adventurous.

Once you’ve seen that, drive north to the Lionhead Group Camp. You’ll see some old dormitory buildings and a shower building near the white sand beach. Those buildings, which are still used today, were once part of a floating timber camp. The camp floated so they could move it around the lake to where the current cut was taking place.

Now, head up the road a mile or so to the Lionhead boat ramp. Park there and take a look at the relic of the Tyee II, sunk in the little bay, creating a picturesque scene. The Tyee II was the last wood-burning steam tugboat on the lake. It pulled a lot of logs in its day. The picture on top shows it circa 1930, while the color picture is a snap of the old hulk resting in the sand.

By the way, Tyee means chief or boss. It also refers to a large Chinook salmon.

Published on June 04, 2023 04:00

June 3, 2023

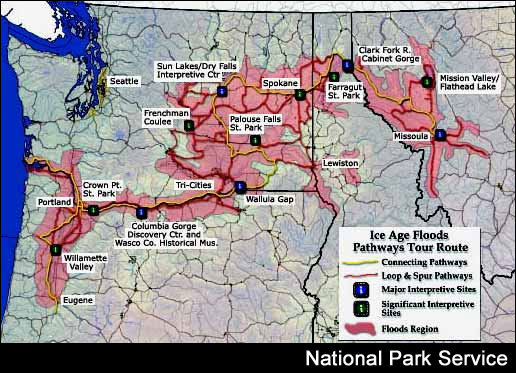

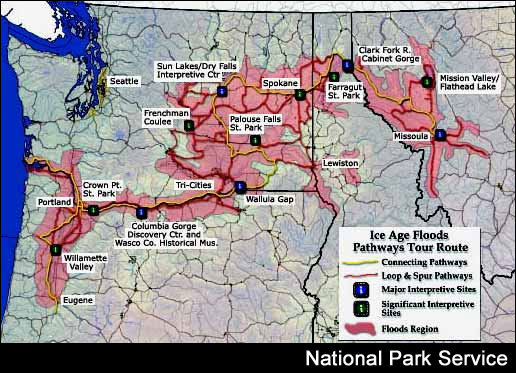

Shaped by Floods (Tap to read)

There is some good-natured competition between the north and south in our big state. Who has the best state parks? The best hunting and best fishing? The craziest politicians?

Bragging rights, for one thing, are really no contest. The Bonneville Flood, which roared through what is now southern Idaho about 12,000 years ago, was a monster. When ancient Lake Bonneville, which covered most of what is now Utah, broke through a natural plug at Red Rock Pass, it sent water crashing down the channel of the Snake River five or six times the flow of the Amazon, tearing out chunks of canyon the size of cars and tumbling the rock into rounded boulders. It drained some 600 cubic miles of water into Columbia and out to the Pacific in a matter of weeks and is said to be the second-biggest flood in geologic history.

Second biggest. So, who had the first? Northern Idaho, of course.

About 15,000 years ago, during the last ice age, a huge glacier blocked the flow of the Clark Fork River near where it enters Lake Pend Oreille. Water backed up into present-day Montana, forming an expansive lake that geologists call Lake Missoula. The glacial lake covered 3,000 square miles, with a depth of up to 2,000 feet.

The ice dam that created Lake Missoula could not contain it forever. When the ice finally gave way--perhaps in the period of a day or two--a massive flood resulted.

You could not have outrun the rush of water called the Spokane Flood. It came ripping out of Idaho and into Washington at up to 80 miles per hour with the force of 500 cubic miles of water behind it. The flow may have run at 13 times the output of the Amazon. It's no wonder it scoured out 200-foot-deep canyons and ripped the topsoil away across 15,000 square miles of what is now Washington State.

The Bonneville Flood happened only once, while the Spokane Flood may have happened again and again—maybe up to 25 times—while ice dams formed and broke away.

Stay dry.

Bragging rights, for one thing, are really no contest. The Bonneville Flood, which roared through what is now southern Idaho about 12,000 years ago, was a monster. When ancient Lake Bonneville, which covered most of what is now Utah, broke through a natural plug at Red Rock Pass, it sent water crashing down the channel of the Snake River five or six times the flow of the Amazon, tearing out chunks of canyon the size of cars and tumbling the rock into rounded boulders. It drained some 600 cubic miles of water into Columbia and out to the Pacific in a matter of weeks and is said to be the second-biggest flood in geologic history.

Second biggest. So, who had the first? Northern Idaho, of course.

About 15,000 years ago, during the last ice age, a huge glacier blocked the flow of the Clark Fork River near where it enters Lake Pend Oreille. Water backed up into present-day Montana, forming an expansive lake that geologists call Lake Missoula. The glacial lake covered 3,000 square miles, with a depth of up to 2,000 feet.

The ice dam that created Lake Missoula could not contain it forever. When the ice finally gave way--perhaps in the period of a day or two--a massive flood resulted.

You could not have outrun the rush of water called the Spokane Flood. It came ripping out of Idaho and into Washington at up to 80 miles per hour with the force of 500 cubic miles of water behind it. The flow may have run at 13 times the output of the Amazon. It's no wonder it scoured out 200-foot-deep canyons and ripped the topsoil away across 15,000 square miles of what is now Washington State.

The Bonneville Flood happened only once, while the Spokane Flood may have happened again and again—maybe up to 25 times—while ice dams formed and broke away.

Stay dry.

Published on June 03, 2023 04:00

June 2, 2023

Idaho History: The Treaty of 1855 Still Matters

Broken treaties with Indians were the norm in the early days of the settlement of the West. So much so that the general assumption is that they are all null and void. That’s not the assumption of the Nez Perce, who are known as Nimiipuu in their language. They have a stronger claim than most tribes because the Treaty of 1855 was signed by all 56 bands of Nimiipuu.

The government often assumed that tribal authority must ultimately rest with a single individual, the “chief” of the Tribe. Most tribes didn’t work that way, so signing a treaty with a leader from one band did not—in the view of the tribes—mean that all bands agreed.

The Tribes Gather

Bands from the Wallawallas, Cayuses, Umatilass, Yakamas, Kootenais, Coeur d’Alenes and others gathered to consider the treaty. They hoped to get an agreement that protect traditional rights and stop the flow of settlers coming into their homeland. Thousands of them came to the Walla Walla Valley and stayed for more than a week to discuss terms. General Isaac Stevens, who was also the first governor of Washington Territory at that time, presided over the negotiations. Unlike the other tribes, all 56 bands of the Nez Perce signed the Treaty of 1855. That puts the Tribe on more solid legal footing than tribes signing other treaties.

So, what did the treaty contain? The Nimiipuu gave up 7.5 million acres of land but significantly retained hunting, fishing, and gathering rights there. Less significant, they were also to get:two schools (including furniture, books, and stationary)two blacksmith shopsa tin shopa gunsmith shopa carpenter shopa wagon and plow shopa sawmilla flour mill13 people to work at and maintain the abovementioned buildings for 20 yearsa hospital stocked with medicines and a trained physician$200,000 (almost 6 million dollars in today’s money)Each tribe’s headman/chief would also receive a house and a stipend of $500 a year ($15,000 today) for twenty years.

Treaty? What Treaty?

White miners paid little attention to the treaty boundaries. That resulted in nearly immediate conflict with most of the Tribes. The Nimiipuu avoided conflict, believing that getting along with the Americans would pay off in the long run. In 1858, the Tribe fought alongside of whites in two battles against other Tribes.

Elias Pierce and others began mining operations on Nez Perce reservation land in 1860, in clear violation of the Treaty of 1855. Many Nimiipuu resented this, but a few saw it as an opportunity.

Getting a Lawyer Involved

Hallalhotsoot, better known as Lawyer, had known the Americans for decades. He was a young boy when his father, Twisted Hair, befriended the Corps of Discovery. A statue in Boise depicts that meeting with Lewis and Clark, showing Lawyer playing at their feet.

Lawyer welcomed the miners and businessmen that followed them. He saw it as an opportunity to sell them livestock and supplies. In his mind, they would take their gold and be gone.

Lawyer signed an agreement that opened up the reservation north of the Clearwater to settlement. His band was to receive $50,000.

Meanwhile, the other bands of the Nez Perce were frustrated, waiting for the promised money and services laid out in the Treaty of 1855.

A Temporary Town

In 1861, the Americans founded the town of Lewiston. Lawyer, who had yet to receive the promised $50,000, confronted the settlers. They assured him that everything was temporary. As soon as the gold was mined, Lewiston would no longer exist. The buildings would be temporary.

By 1862, the “temporary” town of Lewiston had 20,000 residents, and Lawyer still didn’t have his money.

The Treaty of 1863

Congress—better at reading the intentions of those who had settled in and around Lewiston than Lawyer was—drafted a new treaty in 1863. Unlike in the Treaty of 1855, there was a schism between the Nez Perce bands. Lawyer and others signed the new treaty; Chief Joseph and others refused to give away more of their land and their rights. Joseph publicly tore up his copy of the 1855 treaty and rode off.

Seemingly oblivious to the discord in the Tribe over the 1863 treaty, government officials assumed that the new treaty represented the wishes of all Nez Perce. At least, they acted that way.

The “treaty” Nez Perce were viewed by the government as compliant and law-abiding. The “non-treaty” bands were outlaws. The situation simmered along until 1877 when it boiled into the Nez Perce War.

The 1855 Treaty Matters Today

Today, the Treaty of 1855 is so important to the Nez Perce that they make it a part of their branding (see below).

The government often assumed that tribal authority must ultimately rest with a single individual, the “chief” of the Tribe. Most tribes didn’t work that way, so signing a treaty with a leader from one band did not—in the view of the tribes—mean that all bands agreed.

The Tribes Gather

Bands from the Wallawallas, Cayuses, Umatilass, Yakamas, Kootenais, Coeur d’Alenes and others gathered to consider the treaty. They hoped to get an agreement that protect traditional rights and stop the flow of settlers coming into their homeland. Thousands of them came to the Walla Walla Valley and stayed for more than a week to discuss terms. General Isaac Stevens, who was also the first governor of Washington Territory at that time, presided over the negotiations. Unlike the other tribes, all 56 bands of the Nez Perce signed the Treaty of 1855. That puts the Tribe on more solid legal footing than tribes signing other treaties.

So, what did the treaty contain? The Nimiipuu gave up 7.5 million acres of land but significantly retained hunting, fishing, and gathering rights there. Less significant, they were also to get:two schools (including furniture, books, and stationary)two blacksmith shopsa tin shopa gunsmith shopa carpenter shopa wagon and plow shopa sawmilla flour mill13 people to work at and maintain the abovementioned buildings for 20 yearsa hospital stocked with medicines and a trained physician$200,000 (almost 6 million dollars in today’s money)Each tribe’s headman/chief would also receive a house and a stipend of $500 a year ($15,000 today) for twenty years.

Treaty? What Treaty?

White miners paid little attention to the treaty boundaries. That resulted in nearly immediate conflict with most of the Tribes. The Nimiipuu avoided conflict, believing that getting along with the Americans would pay off in the long run. In 1858, the Tribe fought alongside of whites in two battles against other Tribes.

Elias Pierce and others began mining operations on Nez Perce reservation land in 1860, in clear violation of the Treaty of 1855. Many Nimiipuu resented this, but a few saw it as an opportunity.

Getting a Lawyer Involved

Hallalhotsoot, better known as Lawyer, had known the Americans for decades. He was a young boy when his father, Twisted Hair, befriended the Corps of Discovery. A statue in Boise depicts that meeting with Lewis and Clark, showing Lawyer playing at their feet.

Lawyer welcomed the miners and businessmen that followed them. He saw it as an opportunity to sell them livestock and supplies. In his mind, they would take their gold and be gone.

Lawyer signed an agreement that opened up the reservation north of the Clearwater to settlement. His band was to receive $50,000.

Meanwhile, the other bands of the Nez Perce were frustrated, waiting for the promised money and services laid out in the Treaty of 1855.

A Temporary Town

In 1861, the Americans founded the town of Lewiston. Lawyer, who had yet to receive the promised $50,000, confronted the settlers. They assured him that everything was temporary. As soon as the gold was mined, Lewiston would no longer exist. The buildings would be temporary.

By 1862, the “temporary” town of Lewiston had 20,000 residents, and Lawyer still didn’t have his money.

The Treaty of 1863

Congress—better at reading the intentions of those who had settled in and around Lewiston than Lawyer was—drafted a new treaty in 1863. Unlike in the Treaty of 1855, there was a schism between the Nez Perce bands. Lawyer and others signed the new treaty; Chief Joseph and others refused to give away more of their land and their rights. Joseph publicly tore up his copy of the 1855 treaty and rode off.

Seemingly oblivious to the discord in the Tribe over the 1863 treaty, government officials assumed that the new treaty represented the wishes of all Nez Perce. At least, they acted that way.

The “treaty” Nez Perce were viewed by the government as compliant and law-abiding. The “non-treaty” bands were outlaws. The situation simmered along until 1877 when it boiled into the Nez Perce War.

The 1855 Treaty Matters Today

Today, the Treaty of 1855 is so important to the Nez Perce that they make it a part of their branding (see below).

Published on June 02, 2023 04:00

May 31, 2023

Sunbeam Dam (Tap to read)

Today, when gathering energy from the sun through solar collectors is common, the word sunbeam as it pertains to energy is positive. The same was true in 1910 when the Sunbeam Dam was constructed on the Salmon River. It would positively power the Sunbeam mining operation up Jordan Creek from the new dam.

A new power source was needed because the area had been logged out partly to supply fuel for a steam-powered mill. Without logs, that mill couldn’t run. Without the mill to process raw ore, there was no point in mining.

Sunbeam Dam to the rescue. It took 300 tons of concrete to build the dam, which was 95 feet wide and 35 feet high. The dam produced cheap electricity for the mine for a year. But the low grade of the ore coming out of Jordan Creek couldn’t make the operation pay, no matter how cheap the electricity was.

The dam, and other mining properties, were sold at a sheriff’s auction in 1911. The dam never produced electricity again.

One little problem with the dam was that it proved to be an obstacle for migrating salmon. Fish ladders helped solve that problem for several years. The wooden ladders fell into disrepair, and the salmon started to disappear from their spawning grounds. Fish and Game repaired the ladders at least once, but in 1933 the agency tired of the upkeep and decided to blow the dam up.

The dam belonged to someone, though, and dreams of mining riches die hard. Owners talked of using electricity from the dam again in “future” mining operations. They brought suit against the state to stop the destruction of the dam.

The mining company and the state settled out of court, with both parties agreeing to share costs in opening the dam up for migrating salmon. Fish passage was assured in 1934 by the careful application of dynamite.

Today, Sunbeam Dam is a tombstone to itself, a concrete reminder of a failed mining operation.

A new power source was needed because the area had been logged out partly to supply fuel for a steam-powered mill. Without logs, that mill couldn’t run. Without the mill to process raw ore, there was no point in mining.

Sunbeam Dam to the rescue. It took 300 tons of concrete to build the dam, which was 95 feet wide and 35 feet high. The dam produced cheap electricity for the mine for a year. But the low grade of the ore coming out of Jordan Creek couldn’t make the operation pay, no matter how cheap the electricity was.

The dam, and other mining properties, were sold at a sheriff’s auction in 1911. The dam never produced electricity again.

One little problem with the dam was that it proved to be an obstacle for migrating salmon. Fish ladders helped solve that problem for several years. The wooden ladders fell into disrepair, and the salmon started to disappear from their spawning grounds. Fish and Game repaired the ladders at least once, but in 1933 the agency tired of the upkeep and decided to blow the dam up.

The dam belonged to someone, though, and dreams of mining riches die hard. Owners talked of using electricity from the dam again in “future” mining operations. They brought suit against the state to stop the destruction of the dam.

The mining company and the state settled out of court, with both parties agreeing to share costs in opening the dam up for migrating salmon. Fish passage was assured in 1934 by the careful application of dynamite.

Today, Sunbeam Dam is a tombstone to itself, a concrete reminder of a failed mining operation.

Published on May 31, 2023 04:00

May 30, 2023

The Incredible Sinking Farm (Tap to read)

Buhl doesn't get in the news much, which is probably the way the residents like it. In 1937, though, there was national attention on a farm near there. It was dubbed “the sinking farm” in newspaper headlines. Hundreds of tourists flocked to the area, and Buhl residents began hiring themselves out as guides. They even started selling picture postcards of the event.

The farm was on the rim overlooking Salmon Falls Creek Canyon. Strictly speaking, the farm wasn’t so much sinking as it was falling into the canyon as erosion undercut the foundations of the canyon wall. The wall was breaking off in huge chunks like a glacier calving. Some rock would fall into the canyon, and big chunks of it would sink and break and shift, making the land on top of it less than favorable for farming.

Paramount News was there to capture the event on film for newsreels. Geologists from local universities were also on hand to view the phenomenon and explain things to reporters.

Newspaper reports sometimes called it the H.A. Robertson farm. But other reports claimed it was Dr. C. C. Griffith who owned 320 acres on the canyon rim. He was away at his summer house in New York when all the excitement happened. According to a dispatch from the New York Herald-Tribune, which ran in the August 28, 1937, edition of the Idaho Statesman, he wasn’t worried about losing a few acres to the canyon. “What worries him most is the hazard the public is running invading his property.” His ranch manager, Emil Bordewick, was apoplectic about the crowds of people coming to the ranch. There was a deputy on site who wasn’t arresting anyone because wholesale arrests for trespassing might “cause a lot of trouble.” Bordewick had hired a guard. He had informed his employer it would cost $500 a month to “keep these people from getting killed.” And by the way, he wanted a raise.

Meanwhile, experts from the United States Geological Survey were not in a panic. They predicted the sinking would go on for a while. About five million years.

The grumpy ranch manager did see one potential silver lining. Well, a gold lining. He was hoping the new fissures in the earth might reveal a vein of gold.

The farm was on the rim overlooking Salmon Falls Creek Canyon. Strictly speaking, the farm wasn’t so much sinking as it was falling into the canyon as erosion undercut the foundations of the canyon wall. The wall was breaking off in huge chunks like a glacier calving. Some rock would fall into the canyon, and big chunks of it would sink and break and shift, making the land on top of it less than favorable for farming.

Paramount News was there to capture the event on film for newsreels. Geologists from local universities were also on hand to view the phenomenon and explain things to reporters.

Newspaper reports sometimes called it the H.A. Robertson farm. But other reports claimed it was Dr. C. C. Griffith who owned 320 acres on the canyon rim. He was away at his summer house in New York when all the excitement happened. According to a dispatch from the New York Herald-Tribune, which ran in the August 28, 1937, edition of the Idaho Statesman, he wasn’t worried about losing a few acres to the canyon. “What worries him most is the hazard the public is running invading his property.” His ranch manager, Emil Bordewick, was apoplectic about the crowds of people coming to the ranch. There was a deputy on site who wasn’t arresting anyone because wholesale arrests for trespassing might “cause a lot of trouble.” Bordewick had hired a guard. He had informed his employer it would cost $500 a month to “keep these people from getting killed.” And by the way, he wanted a raise.

Meanwhile, experts from the United States Geological Survey were not in a panic. They predicted the sinking would go on for a while. About five million years.

The grumpy ranch manager did see one potential silver lining. Well, a gold lining. He was hoping the new fissures in the earth might reveal a vein of gold.

Published on May 30, 2023 04:00