Rick Just's Blog, page 61

April 29, 2023

Early Irrigation (tap to read)

People who move into the state and even many Idaho natives, often know little about how important irrigation is. Without it, the southern part of the state would be what it had been for millennia, a desert.

This came to mind while I was doing some research on Idaho pioneer Presto Burrell for a family magazine I edit. My family isn’t related to Burrell, but he was important enough in our history that our magazine is called Presto Press, named after him, as was the community of ranches where I grew up, near Blackfoot. It is called Lower Presto.

The April 29, 1910, issue of the Idaho Republican, a Blackfoot newspaper, had the following under the heading, Blackfoot A Historic Spot.

“The newspapers of the state are giving Blackfoot some publicity on account of the fact that this is the fortieth anniversary of the building of the first irrigating ditches in the upper Snake River Valley. Now, within four decades we have more mileage of canals and more acreage of irrigable lands than any other county in the United States, and the marvelous development of forty years, for things move rapidly now.

“It was in 1870 that Fred S. Stevens, Presto Burrell, and Henry Dunn made their first ditches to convey water out upon the soil, and they are all living and making money out of the products being raised each year by the same ditches on the same lands. Their work was experimental, and the present prosperous population is reaping the benefit of the demonstrations they made.”

My great grandparents, Nels and Emma Just moved to the valley in which Presto Burrell settled just a few months after he did. In later years, Emma would be the postmistress for the area, and Nels would suggest the name Presto for the post office. That’s how the area got its name, something Mr. Burrell was never comfortable with.

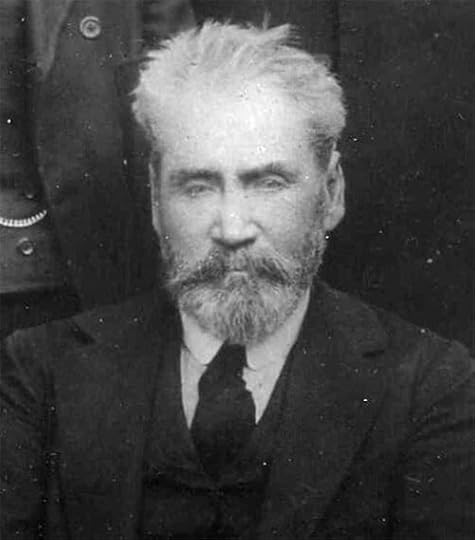

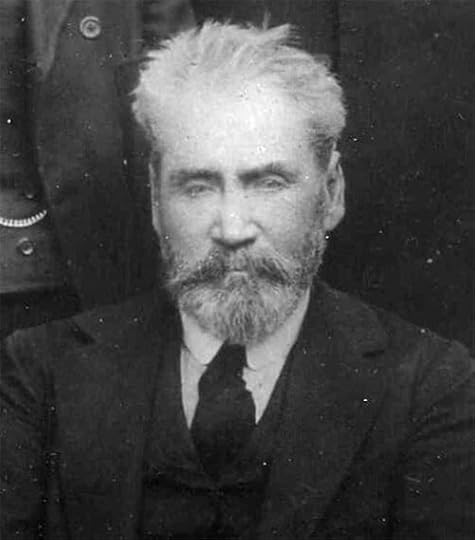

So, I grew up in that little valley where one of the first irrigation ditches in Bingham County was dug by Presto Burrell (photo). Family members—cousins—still farm and ranch in the valley.

This came to mind while I was doing some research on Idaho pioneer Presto Burrell for a family magazine I edit. My family isn’t related to Burrell, but he was important enough in our history that our magazine is called Presto Press, named after him, as was the community of ranches where I grew up, near Blackfoot. It is called Lower Presto.

The April 29, 1910, issue of the Idaho Republican, a Blackfoot newspaper, had the following under the heading, Blackfoot A Historic Spot.

“The newspapers of the state are giving Blackfoot some publicity on account of the fact that this is the fortieth anniversary of the building of the first irrigating ditches in the upper Snake River Valley. Now, within four decades we have more mileage of canals and more acreage of irrigable lands than any other county in the United States, and the marvelous development of forty years, for things move rapidly now.

“It was in 1870 that Fred S. Stevens, Presto Burrell, and Henry Dunn made their first ditches to convey water out upon the soil, and they are all living and making money out of the products being raised each year by the same ditches on the same lands. Their work was experimental, and the present prosperous population is reaping the benefit of the demonstrations they made.”

My great grandparents, Nels and Emma Just moved to the valley in which Presto Burrell settled just a few months after he did. In later years, Emma would be the postmistress for the area, and Nels would suggest the name Presto for the post office. That’s how the area got its name, something Mr. Burrell was never comfortable with.

So, I grew up in that little valley where one of the first irrigation ditches in Bingham County was dug by Presto Burrell (photo). Family members—cousins—still farm and ranch in the valley.

Published on April 29, 2023 04:00

April 28, 2023

The Desmet Fires (tap to read)

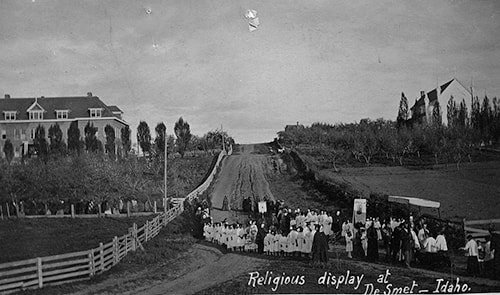

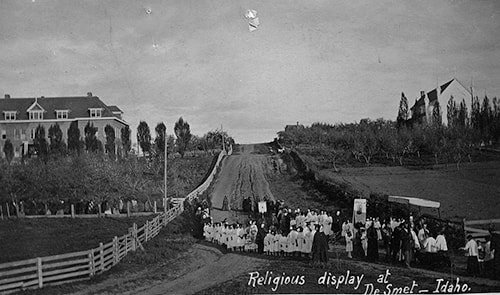

In this postcard image taken sometime before 1939, the Mary Immaculate School in Desmet is on the left, while the Gothic-style Sacred Heart church is on the right. Both structures would end in flames, though 72 years apart.

The first to burn was the Sacred Heart church of the Jesuit Mission on April 2, 1939. Archbishop Seghers, the first bishop of the Pacific Northwest and Alaska, had placed the cornerstone of the church in 1881. A legend about the fate of the church is told at the Museum of North Idaho. An elderly Coeur d’Alene named Agatha Timothy is said to have loved the church so much that she vowed to “take it to heaven with her.” The day after she died a furnace explosion caused the fire that destroyed the building.

The nearby Mary Immaculate School, run by the Sisters of Charity of Providence, was built in 1892 as a boarding school for girls. It was one of many built across the West, with, perhaps, the best of intentions. Often the schools served to educate but also separate Native American students from their families. The school closed in 1974. It burned on Feb. 3, 2011. The landmark building on the hill above DeSmet was on the National Register of Historic Places. The Coeur d’Alene Tribe is planning the Sister’s Building Park and Gathering Area on the site. It will include interpretive panels telling the history of the area.

The first to burn was the Sacred Heart church of the Jesuit Mission on April 2, 1939. Archbishop Seghers, the first bishop of the Pacific Northwest and Alaska, had placed the cornerstone of the church in 1881. A legend about the fate of the church is told at the Museum of North Idaho. An elderly Coeur d’Alene named Agatha Timothy is said to have loved the church so much that she vowed to “take it to heaven with her.” The day after she died a furnace explosion caused the fire that destroyed the building.

The nearby Mary Immaculate School, run by the Sisters of Charity of Providence, was built in 1892 as a boarding school for girls. It was one of many built across the West, with, perhaps, the best of intentions. Often the schools served to educate but also separate Native American students from their families. The school closed in 1974. It burned on Feb. 3, 2011. The landmark building on the hill above DeSmet was on the National Register of Historic Places. The Coeur d’Alene Tribe is planning the Sister’s Building Park and Gathering Area on the site. It will include interpretive panels telling the history of the area.

Published on April 28, 2023 04:00

April 27, 2023

A Radio in Kamiah (tap to read)

In the early days of radio, it was common for communities to come together to purchase a receiver. Radios were expensive and not affordable for everyone, so people often pooled their resources to buy a radio that could be shared among the community. This was particularly common in rural areas, where the cost of a radio was even more prohibitive.

These shared radios were often placed in a central location, such as a community center or a local store, where people could come and listen to news, music, and other broadcasts. In some cases, people would take turns bringing the radio home for a day or two so that they could listen to it in the privacy of their own homes.

The community of Kamiah came together in March, 1923 to purchase a receiver. The contract read:

“We, the undersigned, donate Three Dollars ($3.00) to be used by Jack Dundas and Hubert Renshaw in the purchase and installing of a Radio Receiving Machine. This Machine will be installed in Legion Hall, and belong to the undersigned and to those who wish to donate the same sum later. This fee will entitle me and my family (or if single, the company of one other) to free admission to all concerts.”

Forty-eight other residents sign the document and pitched in $3. The Receiver cost a little more than the $150 they raised. No word on how they made up the difference. That first receiver was terrible and the community got little use out of it. By the time they decided to ditch it, most everyone had begun to buy much less expensive sets of their own.

These shared radios were often placed in a central location, such as a community center or a local store, where people could come and listen to news, music, and other broadcasts. In some cases, people would take turns bringing the radio home for a day or two so that they could listen to it in the privacy of their own homes.

The community of Kamiah came together in March, 1923 to purchase a receiver. The contract read:

“We, the undersigned, donate Three Dollars ($3.00) to be used by Jack Dundas and Hubert Renshaw in the purchase and installing of a Radio Receiving Machine. This Machine will be installed in Legion Hall, and belong to the undersigned and to those who wish to donate the same sum later. This fee will entitle me and my family (or if single, the company of one other) to free admission to all concerts.”

Forty-eight other residents sign the document and pitched in $3. The Receiver cost a little more than the $150 they raised. No word on how they made up the difference. That first receiver was terrible and the community got little use out of it. By the time they decided to ditch it, most everyone had begun to buy much less expensive sets of their own.

Published on April 27, 2023 04:00

April 26, 2023

Top This One! (tap to read)

Once you’ve been a member of the U.S. Senate and a vice presidential candidate, what do you do with the rest of your life? The answer, for Glen Taylor, was to make hair pieces.

After running unsuccessfully for office several times, Taylor became a U.S. Senator from Idaho in 1944, defeating incumbent D. Worth Clark in the primary and Gov. C.A. Bottolfsen in the general election. To say he was colorful would be to understate it.

As a young man he played the vaudeville circuit with his brothers as the Taylor Players. During a performance of the group in Montana, he met an usher named Dora Pike. He married her in 1928 and they formed their own vaudeville act called the Glendora Players. When a son came along, Arod (Dora spelled backwards), he was added to the act. That’s Glen, Arod, and Dora sitting in front in the picture with backing players behind.

What he learned in vaudeville served him well in politics. He campaigned often on horseback wearing a ten-gallon hat and singing songs encouraging voters to elect him. When they finally did, the Singing Cowboy famously rode his horse Nugget up the steps of the capitol. He found housing tight in Washington, DC, so he stood out in front of the capitol singing “O give us a home, near the Capitol dome, with a yard for two children to play...” to the tune of Home on the Range. The stunt worked.

Taylor was an unabashed liberal, perhaps the most so of any elected politician from Idaho in history. He was an early proponent of civil rights and was a stalwart advocate for peace. In 1948 he ran for vice president on the Progressive Party ticket. That all but guaranteed that he would not be elected to a second term from conservative Idaho.

Taylor tried a lot of things to make his way in life following his defeat in 1950. Finally, it occurred to him that there might be some money in making hairpieces for men. He had made his own hairpiece and wore it for the first time in an election the year he won, 1944. A good sign.

He perfected and patented a design for a hairpiece and named it the Taylor Topper. In the 50s and 60s little ads for the Taylor Topper were a familiar component of magazines for men. He did well with them. Taylor died in 1984, but his son, Greg, owns the company, still. Today it’s called Taylormade and is based in Millbrae, California, where they custom make high-end hair pieces for men and women.

Glen Taylor, white hat, and his band.

Glen Taylor, white hat, and his band.

After running unsuccessfully for office several times, Taylor became a U.S. Senator from Idaho in 1944, defeating incumbent D. Worth Clark in the primary and Gov. C.A. Bottolfsen in the general election. To say he was colorful would be to understate it.

As a young man he played the vaudeville circuit with his brothers as the Taylor Players. During a performance of the group in Montana, he met an usher named Dora Pike. He married her in 1928 and they formed their own vaudeville act called the Glendora Players. When a son came along, Arod (Dora spelled backwards), he was added to the act. That’s Glen, Arod, and Dora sitting in front in the picture with backing players behind.

What he learned in vaudeville served him well in politics. He campaigned often on horseback wearing a ten-gallon hat and singing songs encouraging voters to elect him. When they finally did, the Singing Cowboy famously rode his horse Nugget up the steps of the capitol. He found housing tight in Washington, DC, so he stood out in front of the capitol singing “O give us a home, near the Capitol dome, with a yard for two children to play...” to the tune of Home on the Range. The stunt worked.

Taylor was an unabashed liberal, perhaps the most so of any elected politician from Idaho in history. He was an early proponent of civil rights and was a stalwart advocate for peace. In 1948 he ran for vice president on the Progressive Party ticket. That all but guaranteed that he would not be elected to a second term from conservative Idaho.

Taylor tried a lot of things to make his way in life following his defeat in 1950. Finally, it occurred to him that there might be some money in making hairpieces for men. He had made his own hairpiece and wore it for the first time in an election the year he won, 1944. A good sign.

He perfected and patented a design for a hairpiece and named it the Taylor Topper. In the 50s and 60s little ads for the Taylor Topper were a familiar component of magazines for men. He did well with them. Taylor died in 1984, but his son, Greg, owns the company, still. Today it’s called Taylormade and is based in Millbrae, California, where they custom make high-end hair pieces for men and women.

Glen Taylor, white hat, and his band.

Glen Taylor, white hat, and his band.

Published on April 26, 2023 04:00

April 25, 2023

Our Horseshoe Town (tap to read)

Time for another in our series called Idaho Then and Now.

Utopian communities were common in 19th Century America. The still new country attracted people who envisioned a perfect society.

One such community was New Plymouth, Idaho. William E. Smythe founded the New Plymouth Society of Chicago with aim of building a planned community in Idaho’s Payette River Valley. Unlike some utopian community, this one wasn’t based on religious or moral principles but rather on planning and irrigation.

On April 17, 1885 the Idaho Daily Statesman carried a story that quoted Smythe. “Each colonist will purchase 20 acres of irrigated land and 20 shares of stock in the Plymouth company,” Smythe said. “He will also be entitled to an acre in the central area set apart for the village site if he will build a house upon it and make his home there.”

The town itself was platted out in a horseshoe shape with the open end of the horseshoe facing north toward the Payette River (Google Earth image below). Shareholders’ farms and orchards would all be within two or three miles of town.

The paper quoted Smythe, “There is to be nothing communistic about this New Plymouth. There is to be very little co-operation even, in the technical sense. The only property which is to be owned in common is the town hall, which is to be modeled after the Idaho building at the World’s Fair.” The fair had been held in Chicago in 1893. The community would have a library and an electric lighting plant.

The town was incorporated in February, 1896. It started out with a couple hundred residents, each with at least $1,000 in cash to their name, as was required by the colony. Today it’s population is about 1,500.

The shape of the town is about the only clue left about its origins. Citizens call it the “World’s Biggest Horseshoe.”

Planned communities today in Idaho tend to come in a couple of forms. The first type, not unlike New Plymouth, is built with an eye on planned amenities. Hidden Springs and Avimor near Boise and Eagle, respectively, are examples. The other type of planned community that we hear about involves a belief that some form of political or natural disaster is due. These are the survivalists who are looking for someplace to ride out the storm. The redoubt movement is an example.

Utopian communities were common in 19th Century America. The still new country attracted people who envisioned a perfect society.

One such community was New Plymouth, Idaho. William E. Smythe founded the New Plymouth Society of Chicago with aim of building a planned community in Idaho’s Payette River Valley. Unlike some utopian community, this one wasn’t based on religious or moral principles but rather on planning and irrigation.

On April 17, 1885 the Idaho Daily Statesman carried a story that quoted Smythe. “Each colonist will purchase 20 acres of irrigated land and 20 shares of stock in the Plymouth company,” Smythe said. “He will also be entitled to an acre in the central area set apart for the village site if he will build a house upon it and make his home there.”

The town itself was platted out in a horseshoe shape with the open end of the horseshoe facing north toward the Payette River (Google Earth image below). Shareholders’ farms and orchards would all be within two or three miles of town.

The paper quoted Smythe, “There is to be nothing communistic about this New Plymouth. There is to be very little co-operation even, in the technical sense. The only property which is to be owned in common is the town hall, which is to be modeled after the Idaho building at the World’s Fair.” The fair had been held in Chicago in 1893. The community would have a library and an electric lighting plant.

The town was incorporated in February, 1896. It started out with a couple hundred residents, each with at least $1,000 in cash to their name, as was required by the colony. Today it’s population is about 1,500.

The shape of the town is about the only clue left about its origins. Citizens call it the “World’s Biggest Horseshoe.”

Planned communities today in Idaho tend to come in a couple of forms. The first type, not unlike New Plymouth, is built with an eye on planned amenities. Hidden Springs and Avimor near Boise and Eagle, respectively, are examples. The other type of planned community that we hear about involves a belief that some form of political or natural disaster is due. These are the survivalists who are looking for someplace to ride out the storm. The redoubt movement is an example.

Published on April 25, 2023 04:00

April 24, 2023

Idaho's Territorial Capitol (tap to read)

As most Idahoan’s know, Lewiston was the first territorial capital. Even as territorial governor William H. Wallace arrived in Lewiston in July of 1863, the fate of the first capital was sealed, though no one knew it. I use that old saw about Lewiston’s fate being “sealed,” knowing full well that not a few of you will groan. Those not groaning, just wait a few more words.

Idaho Territory at its inception included what is now Montana. The size of the territory was going to make governing it from anywhere difficult. Fortunately, an influx of gold-seekers into mining camps across the Bitterroots led quickly to the formation of Montana Territory in May 1864.

Miners were also pouring into camps in the Boise Basin. A census of the territory in September 1863 showed a total population of 32,342, including 12,000 who would soon be in Montana. That left 20,342 in what would end up in the territory/state we know today. Boise County, which included the boomtowns of Idaho City and Atlanta, boasted 16,000 residents. With four times the residents in the south as in the north—the census missed Franklin and Paris for some reason—a seat of government in southern Idaho made sense.

It’s important to note that the Idaho Territorial Legislature had yet to designate any town as the seat of government at that point. In November, 1864, the second legislature assembled in Lewiston. Legislators from the northern part of the territory tried to dodge the issue of naming a capital by proposing to ask Congress to create a new Idaho Territory to include the panhandle and eastern Washington. Southern Idaho could do whatever it wanted. This would have left the southern part of the territory shaped something like Iowa (how would Easterners ever tell them apart??).

The southern legislators had enough clout to stop that idea, and they had enough votes to establish Boise as the permanent capital of Idaho Territory.

At the end of the second territorial legislature, Lewiston Lawyers fought the decision. They claimed the legislature had convened on the wrong day and thus many legislators weren’t really legislators.

Then Territorial Governor Caleb Lyon, perhaps not having the stomach for this fight, simply left the territory. Quoting the Idaho State Historical Society Reference series on the subject, “Boise partisans tried to swipe the territorial seal and archives in order to remove them to Boise, Lewiston established an armed guard over the papers themselves. Both sides used loud language about each other, and there were petitions to Congress and hearings before a probate judge. His was not the proper court to hear the matter, but the proper court was incapacitated for reasons which embarrassed Lewiston. The territorial supreme court was not yet organized. The judges had not yet gotten together, and anyway the court was supposed to assemble in the capital and nobody knew where the capital was.”

During all this muddle, a new secretary of the territory, C. Dewitt Smith arrived in town. As the acting governor, in Governor Lyon’s absence, he called up troops from Ft. Lapwai and seized the territorial seal and took it to Boise. The territory organized its supreme court, and the court determined that the second territorial legislature, despite confusion about official dates, was legal and thus the capital was Boise. And thus my lame joke about Lewiston’s fate being sealed. Sorry Lewiston.

The photo is of the first territorial capitol. The building no longer exists, but history buffs and students from Lewiston High School’s senior construction class built a nice replica a few blocks away from the original site in 2013.

The photo is of the first territorial capitol. The building no longer exists, but history buffs and students from Lewiston High School’s senior construction class built a nice replica a few blocks away from the original site in 2013.

Idaho Territory at its inception included what is now Montana. The size of the territory was going to make governing it from anywhere difficult. Fortunately, an influx of gold-seekers into mining camps across the Bitterroots led quickly to the formation of Montana Territory in May 1864.

Miners were also pouring into camps in the Boise Basin. A census of the territory in September 1863 showed a total population of 32,342, including 12,000 who would soon be in Montana. That left 20,342 in what would end up in the territory/state we know today. Boise County, which included the boomtowns of Idaho City and Atlanta, boasted 16,000 residents. With four times the residents in the south as in the north—the census missed Franklin and Paris for some reason—a seat of government in southern Idaho made sense.

It’s important to note that the Idaho Territorial Legislature had yet to designate any town as the seat of government at that point. In November, 1864, the second legislature assembled in Lewiston. Legislators from the northern part of the territory tried to dodge the issue of naming a capital by proposing to ask Congress to create a new Idaho Territory to include the panhandle and eastern Washington. Southern Idaho could do whatever it wanted. This would have left the southern part of the territory shaped something like Iowa (how would Easterners ever tell them apart??).

The southern legislators had enough clout to stop that idea, and they had enough votes to establish Boise as the permanent capital of Idaho Territory.

At the end of the second territorial legislature, Lewiston Lawyers fought the decision. They claimed the legislature had convened on the wrong day and thus many legislators weren’t really legislators.

Then Territorial Governor Caleb Lyon, perhaps not having the stomach for this fight, simply left the territory. Quoting the Idaho State Historical Society Reference series on the subject, “Boise partisans tried to swipe the territorial seal and archives in order to remove them to Boise, Lewiston established an armed guard over the papers themselves. Both sides used loud language about each other, and there were petitions to Congress and hearings before a probate judge. His was not the proper court to hear the matter, but the proper court was incapacitated for reasons which embarrassed Lewiston. The territorial supreme court was not yet organized. The judges had not yet gotten together, and anyway the court was supposed to assemble in the capital and nobody knew where the capital was.”

During all this muddle, a new secretary of the territory, C. Dewitt Smith arrived in town. As the acting governor, in Governor Lyon’s absence, he called up troops from Ft. Lapwai and seized the territorial seal and took it to Boise. The territory organized its supreme court, and the court determined that the second territorial legislature, despite confusion about official dates, was legal and thus the capital was Boise. And thus my lame joke about Lewiston’s fate being sealed. Sorry Lewiston.

The photo is of the first territorial capitol. The building no longer exists, but history buffs and students from Lewiston High School’s senior construction class built a nice replica a few blocks away from the original site in 2013.

The photo is of the first territorial capitol. The building no longer exists, but history buffs and students from Lewiston High School’s senior construction class built a nice replica a few blocks away from the original site in 2013.

Published on April 24, 2023 04:00

April 23, 2023

The Mankiller (tap to read)

For your entertainment, today, a dubious clip from the Elk City News, 1908.

Few people in town on the prairie had seen an automobile until this summer, so when one of the “red devils” stopped for a few minutes in Elk City, the curious inhabitants gazed at the snorting demon with a mixture of fear and awe, and the owner who had entered the one general store to make a purchase, heard one rustic remark; “I’ll bet it’s a mankiller.” “O’course it is,” assured the other. “Look at that number on the back of the car. That shows how many people its run over. That’s accordin’ to law. Now if that feller was to run over anybody here it would be our duty to telephone that number—1284—to the next town ahead.” “And what would they do?” demanded the interested auditors. “Why the police would stop him and change his number to 1285.”

Few people in town on the prairie had seen an automobile until this summer, so when one of the “red devils” stopped for a few minutes in Elk City, the curious inhabitants gazed at the snorting demon with a mixture of fear and awe, and the owner who had entered the one general store to make a purchase, heard one rustic remark; “I’ll bet it’s a mankiller.” “O’course it is,” assured the other. “Look at that number on the back of the car. That shows how many people its run over. That’s accordin’ to law. Now if that feller was to run over anybody here it would be our duty to telephone that number—1284—to the next town ahead.” “And what would they do?” demanded the interested auditors. “Why the police would stop him and change his number to 1285.”

Published on April 23, 2023 04:00

April 22, 2023

The Whitebird Bridge (tap to read)

Do you remember the switchback road that snaked up the mountain at White Bird? If you wanted to go by car from the northern part of the state to the southern, or vice versa, you had no choice but to tackle that hill.

Coming from the south, the road brought you out of the Salmon River canyon and up onto the prairie, lifting you about 2,700 feet on a corkscrew path. It was a thrill to look down into the draws along the road to see the carcasses of cars that had failed to negotiate a turn. Legend has it that a woman from Massachusetts refused to ride down the hill with her husband. He drove the car slowly while she walked behind.

But all that changed in 1975 when the 811-foot span was dedicated. Governor Cecil D. Andrus is shown in this Idaho Transportation Department photo at the dedication. He famously referred to the old Highway 95 as a “goat path.”

The project, building the road and building the bridge, took ten years. It was a challenge just getting the 26 steel bridge sections to the site from Indiana, where they were made. They weighed between 116,000 and 148,000 pounds. Each section arrived by truck. The first one slipped off the flatbed near Riggins, causing minor injury to the rear steering unit driver. It took 45 days to get the steel sections on site so they could be assembled.

Today traveling the stretch between White Bird and the prairie above is easy enough, though it still provides some heart-stopping views into the valley. You can even spot the Seven Devils in the distance from the top of the hill if you know where to look. The old road is still in place, maintained now as a gravel road. I’ve taken it a few times in a sports car just for grins.

Governor Cecil Andrus working the crowd at the opening of the Whitebird Bridge.

Governor Cecil Andrus working the crowd at the opening of the Whitebird Bridge.

Coming from the south, the road brought you out of the Salmon River canyon and up onto the prairie, lifting you about 2,700 feet on a corkscrew path. It was a thrill to look down into the draws along the road to see the carcasses of cars that had failed to negotiate a turn. Legend has it that a woman from Massachusetts refused to ride down the hill with her husband. He drove the car slowly while she walked behind.

But all that changed in 1975 when the 811-foot span was dedicated. Governor Cecil D. Andrus is shown in this Idaho Transportation Department photo at the dedication. He famously referred to the old Highway 95 as a “goat path.”

The project, building the road and building the bridge, took ten years. It was a challenge just getting the 26 steel bridge sections to the site from Indiana, where they were made. They weighed between 116,000 and 148,000 pounds. Each section arrived by truck. The first one slipped off the flatbed near Riggins, causing minor injury to the rear steering unit driver. It took 45 days to get the steel sections on site so they could be assembled.

Today traveling the stretch between White Bird and the prairie above is easy enough, though it still provides some heart-stopping views into the valley. You can even spot the Seven Devils in the distance from the top of the hill if you know where to look. The old road is still in place, maintained now as a gravel road. I’ve taken it a few times in a sports car just for grins.

Governor Cecil Andrus working the crowd at the opening of the Whitebird Bridge.

Governor Cecil Andrus working the crowd at the opening of the Whitebird Bridge.

Published on April 22, 2023 04:00

April 21, 2023

Spuds in Space? (tap to read)

Okay, what would YOU call your potato equipment manufacturing business? If you were one of the Hobbs brothers who started their business in a potato cellar northwest of Blackfoot, you’d call it Spudnik. It was 1958. Get it? Russian satellite?

Carl and Leo Hobbs designed and developed the Spudnik Scooper. The company went on to develop harvesters, conveyors, planters, self-unloading truck beds and much other potato-oriented equipment. In 2001 they entered into a joint partnership with the Grimme Group of companies, headquartered in Damme, Germany, which is the largest potato equipment manufacturer in the world.

Spudnik is still headquartered in Blackfoot, the “Potato Capital of the World,” if you didn’t know. The photo is of their downtown Blackfoot office in 1960.

Carl and Leo Hobbs designed and developed the Spudnik Scooper. The company went on to develop harvesters, conveyors, planters, self-unloading truck beds and much other potato-oriented equipment. In 2001 they entered into a joint partnership with the Grimme Group of companies, headquartered in Damme, Germany, which is the largest potato equipment manufacturer in the world.

Spudnik is still headquartered in Blackfoot, the “Potato Capital of the World,” if you didn’t know. The photo is of their downtown Blackfoot office in 1960.

Published on April 21, 2023 04:00

April 20, 2023

Shoup at Sand Creek (tap to read)

History is full of imperfect men. How could it be otherwise?

Idaho’s last territorial governor and the first governor of the State of Idaho was George L. Shoup. He didn’t serve long as Idaho’s governor. The Idaho Legislature elected him to the US Senate just a few weeks after he had been appointed governor. He served in the senate for ten years.

There is much one can say about Shoup that is positive. He was a strong force in shaping Idaho in its early days. Strong enough that he is honored in the National Statuary Hall Collection at the US Capitol. Each state gets only two statues. Idaho chose Shoup and Senator William E. Borah for that honor (photo).

Among his many business and political accomplishments is one that is a mere footnote in his biography, but it is one that has always troubled me. Col. George L. Shoup was a key leader of what is most often referred to today as the Sand Creek Massacre in Colorado. Here’s how Wikipedia describes it:

The Sand Creek massacre (also known as the Chivington massacre, the Battle of Sand Creek or the massacre of Cheyenne Indians) was a massacre in the American Indian Wars that occurred on November 29, 1864, when a 675-man force of Colorado U.S. Volunteer Cavalry attacked and destroyed a village of Cheyenne and Arapaho in southeastern Colorado Territory, killing and mutilating an estimated 70–163 Native Americans, about two-thirds of whom were women and children. The location has been designated the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site and is administered by the National Park Service.

It is too complex an issue for a short post to examine all sides of the story and better understand the motives of those involved. To his credit, many times in his later life Shoup showed a willingness to work with Native Americans and he supported fair treatment for them. It is also worth noting that two troop commanders, Captain Silas Soule and Lt. Joseph Cramer, refused to have their soldiers engage. They are seen as heroes today by many.

Idaho’s last territorial governor and the first governor of the State of Idaho was George L. Shoup. He didn’t serve long as Idaho’s governor. The Idaho Legislature elected him to the US Senate just a few weeks after he had been appointed governor. He served in the senate for ten years.

There is much one can say about Shoup that is positive. He was a strong force in shaping Idaho in its early days. Strong enough that he is honored in the National Statuary Hall Collection at the US Capitol. Each state gets only two statues. Idaho chose Shoup and Senator William E. Borah for that honor (photo).

Among his many business and political accomplishments is one that is a mere footnote in his biography, but it is one that has always troubled me. Col. George L. Shoup was a key leader of what is most often referred to today as the Sand Creek Massacre in Colorado. Here’s how Wikipedia describes it:

The Sand Creek massacre (also known as the Chivington massacre, the Battle of Sand Creek or the massacre of Cheyenne Indians) was a massacre in the American Indian Wars that occurred on November 29, 1864, when a 675-man force of Colorado U.S. Volunteer Cavalry attacked and destroyed a village of Cheyenne and Arapaho in southeastern Colorado Territory, killing and mutilating an estimated 70–163 Native Americans, about two-thirds of whom were women and children. The location has been designated the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site and is administered by the National Park Service.

It is too complex an issue for a short post to examine all sides of the story and better understand the motives of those involved. To his credit, many times in his later life Shoup showed a willingness to work with Native Americans and he supported fair treatment for them. It is also worth noting that two troop commanders, Captain Silas Soule and Lt. Joseph Cramer, refused to have their soldiers engage. They are seen as heroes today by many.

Published on April 20, 2023 04:00