Rick Just's Blog, page 60

May 10, 2023

Inventing Teenagers (Tap to read)

Parents, of course, you love your children. But be honest, haven’t you once or twice wished there was no such thing as a teenager? There was a time in Idaho history, and world history for that matter when they did not exist.

The term teenager didn’t start making its way into popular usage until the 1930s and 1940s. The first instance of the word that I found in an Idaho paper was in the Statesman in 1941. It didn’t come up again there until 1943.

Teenage came along a little earlier, though newspapers were slow to standardize it. They used teen age, ‘teen age, “teen” age, and teen-age, depending on the whim of typesetters, perhaps. An expert on the teen-age from Chicago was speaking at a Boise church convention on “the boy problem” in 1914. Thank goodness we’ve now solved that one.

This wasn’t just about semantics. In a sense, there were no teenagers throughout most of recorded history. There were children who toddled around until they were five or six or seven, not contributing much to a family. Once they could start working at some menial labor, that’s what they did, simply becoming more useful as they got older.

The introduction of standardized education and child labor laws began to change this in the 19th century. Some scholars attribute the invention of the teenager, more or less as we know them today, to the automobile. Cars provided freedom for young people to occasionally get away from their parents. Dating became much more common. Then consolidated high schools began to use buses to bring students from further and further away. There they were, together, learning, dating, and beginning to dress in their own fashions in the 1950s (picture). Voila! Teenagers!

I have done no research on the subject, but feel confident that eye-rolling and insolence came into vogue about the same time as the word teenager.

The term teenager didn’t start making its way into popular usage until the 1930s and 1940s. The first instance of the word that I found in an Idaho paper was in the Statesman in 1941. It didn’t come up again there until 1943.

Teenage came along a little earlier, though newspapers were slow to standardize it. They used teen age, ‘teen age, “teen” age, and teen-age, depending on the whim of typesetters, perhaps. An expert on the teen-age from Chicago was speaking at a Boise church convention on “the boy problem” in 1914. Thank goodness we’ve now solved that one.

This wasn’t just about semantics. In a sense, there were no teenagers throughout most of recorded history. There were children who toddled around until they were five or six or seven, not contributing much to a family. Once they could start working at some menial labor, that’s what they did, simply becoming more useful as they got older.

The introduction of standardized education and child labor laws began to change this in the 19th century. Some scholars attribute the invention of the teenager, more or less as we know them today, to the automobile. Cars provided freedom for young people to occasionally get away from their parents. Dating became much more common. Then consolidated high schools began to use buses to bring students from further and further away. There they were, together, learning, dating, and beginning to dress in their own fashions in the 1950s (picture). Voila! Teenagers!

I have done no research on the subject, but feel confident that eye-rolling and insolence came into vogue about the same time as the word teenager.

Published on May 10, 2023 04:00

May 9, 2023

Counties and States that Measure Up (Tap to read)

You’ve heard that Idaho’s largest county, Idaho County, is larger than three states, Rhode Island, Delaware, and Connecticut. In fact, you’ll sometimes hear that you could put all three of those states inside Idaho County.

Take this with a grain of salt. The area of a state seems to be determined by… what? Humidity? You’ll find numerous conflicting numbers if you Google the area of our smallest states. Rhode Island’s area is 1,045 square miles. Unless it’s 1,545 square miles. Or 1,037 square miles. Delaware comes in at 2,489 square miles or 1,982 square miles and 1,954 square miles. Comparatively gigantic, Connecticut is 5,567 square miles, or possibly 5,028 square miles, or 5,018 square miles.

Not surprisingly, when asking about the area of Idaho County in square miles, you get a couple of answers, 8,503 or 8,477 square miles.

If you took the lowest numbers for the area of the three smallest states, yes, they could be shoehorned into Idaho County. But use the highest numbers, and only any two of the three would fit, with nearly enough left over to cram in the third one.

I thought it might be fun to see how Idaho’s smallest county, Clark, measures up to small states. Clark County is 1,765 square miles. Now, don’t make me fit a jigsaw piece into a differently shaped hole, but if the square miles in Clark County were SQUARE, Rhode Island, the smallest state in the US, would fit easily inside of Idaho’s smallest county.

How about the number of counties in Idaho compared with other states? Idaho has 44 counties. The state with the fewest is Delaware, with three. Unless you count Rhode Island and Connecticut, which don’t bother having any counties at all. And, of course, Louisiana doesn’t call its political subdivisions counties. They are parishes, and there are 64 of them.

Do we really need a drum roll to announce the state with the most counties? Texas, at 254.

None of this useless information is likely to show up on a test, fourth graders, so relax.

Take this with a grain of salt. The area of a state seems to be determined by… what? Humidity? You’ll find numerous conflicting numbers if you Google the area of our smallest states. Rhode Island’s area is 1,045 square miles. Unless it’s 1,545 square miles. Or 1,037 square miles. Delaware comes in at 2,489 square miles or 1,982 square miles and 1,954 square miles. Comparatively gigantic, Connecticut is 5,567 square miles, or possibly 5,028 square miles, or 5,018 square miles.

Not surprisingly, when asking about the area of Idaho County in square miles, you get a couple of answers, 8,503 or 8,477 square miles.

If you took the lowest numbers for the area of the three smallest states, yes, they could be shoehorned into Idaho County. But use the highest numbers, and only any two of the three would fit, with nearly enough left over to cram in the third one.

I thought it might be fun to see how Idaho’s smallest county, Clark, measures up to small states. Clark County is 1,765 square miles. Now, don’t make me fit a jigsaw piece into a differently shaped hole, but if the square miles in Clark County were SQUARE, Rhode Island, the smallest state in the US, would fit easily inside of Idaho’s smallest county.

How about the number of counties in Idaho compared with other states? Idaho has 44 counties. The state with the fewest is Delaware, with three. Unless you count Rhode Island and Connecticut, which don’t bother having any counties at all. And, of course, Louisiana doesn’t call its political subdivisions counties. They are parishes, and there are 64 of them.

Do we really need a drum roll to announce the state with the most counties? Texas, at 254.

None of this useless information is likely to show up on a test, fourth graders, so relax.

Published on May 09, 2023 04:00

May 8, 2023

The Tragedy of Herbert Lemp (Tap to read)

As I search through back issues of Idaho papers looking for something of interest for this series, I sometimes get an uneasy sense of foreboding. From my vantage point, decades hence, I often know what is about to happen as I skim stories leading up to a date. Such was the case as I followed the campaign for mayor of Boise in the 1927 newspapers. The Idaho Statesman headline on Wednesday morning, April 6, 1927, read, “LEMP OVERWHELMS EAGLESON FOR MAYOR THREE TO ONE.”

It was the headline of May 2nd I was looking for: “HERBERT LEMP INJURED DURING POLO MATCH.” Lemp was the captain of the Boise polo team. In the first practice game of the season, he was riding the ball toward the goal in the fourth chukker when his horse, Craven, stumbled. That sent the mayor-elect head-first into the dirt. The first report of his condition said that he was resting comfortably at St. Lukes and that friends were confident he would be able to attend his inauguration the next day.

Alas, no. The headline on May 7th read, “MAYOR H.F. LEMP DIES OF INJURIES SUFFERED IN FALL.” The story went on: “Herbert Frederick Lemp, mayor of Boise, died Friday morning at 7 o’clock, in St. Luke’s hospital.

“The fractious caprice of a half-tamed polo pony, which hurled the city’s mayor to the ground during a practice game last Sunday afternoon inflicted the injury which took his life.

“The death was announced to Boise citizens by the tolling of the Central fire state bell, which continued at 20-second intervals for an hour, and by flags flying at half-staff.”

Though he never got to serve Herbert, was not the first Lemp elected mayor of Boise. His father, John, turned a teacup full of Idaho City gold dust into a fortune through investments in brewing and real estate, making him the wealthiest man in Ada County. John Lemp served as mayor of Boise for a year, 1875-76.

Herbert Lemp on his horse, Scrambled Eggs, on the steps of the capitol.

Herbert Lemp on his horse, Scrambled Eggs, on the steps of the capitol.

It was the headline of May 2nd I was looking for: “HERBERT LEMP INJURED DURING POLO MATCH.” Lemp was the captain of the Boise polo team. In the first practice game of the season, he was riding the ball toward the goal in the fourth chukker when his horse, Craven, stumbled. That sent the mayor-elect head-first into the dirt. The first report of his condition said that he was resting comfortably at St. Lukes and that friends were confident he would be able to attend his inauguration the next day.

Alas, no. The headline on May 7th read, “MAYOR H.F. LEMP DIES OF INJURIES SUFFERED IN FALL.” The story went on: “Herbert Frederick Lemp, mayor of Boise, died Friday morning at 7 o’clock, in St. Luke’s hospital.

“The fractious caprice of a half-tamed polo pony, which hurled the city’s mayor to the ground during a practice game last Sunday afternoon inflicted the injury which took his life.

“The death was announced to Boise citizens by the tolling of the Central fire state bell, which continued at 20-second intervals for an hour, and by flags flying at half-staff.”

Though he never got to serve Herbert, was not the first Lemp elected mayor of Boise. His father, John, turned a teacup full of Idaho City gold dust into a fortune through investments in brewing and real estate, making him the wealthiest man in Ada County. John Lemp served as mayor of Boise for a year, 1875-76.

Herbert Lemp on his horse, Scrambled Eggs, on the steps of the capitol.

Herbert Lemp on his horse, Scrambled Eggs, on the steps of the capitol.

Published on May 08, 2023 04:00

May 7, 2023

Gretchen Fraser (Tap to read)

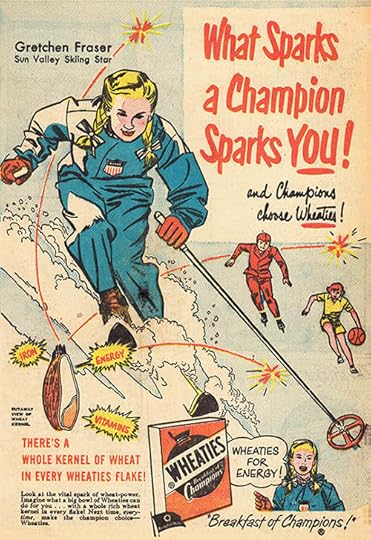

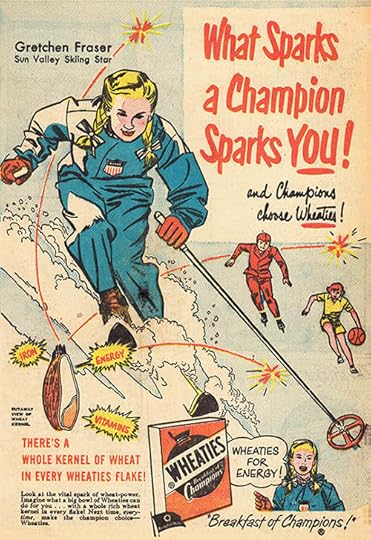

Some of our more famous Idahoans weren’t born here. They chose Idaho, which simply indicates their good sense.

Gretchen Fraser was born in Tacoma, Washington. She fell in love with Idaho—and fell in love—in 1938 when she came to Sun Valley to compete in the Harriman Cup ski race. She met her future husband, Donald Fraser on the train traveling to Idaho. Donald had been a member of the 1936 US Olympic ski team. The two were married in 1939 and took up residence in Sun Valley. Both became members of the 1940 US Olympic ski team.

The 1940 games were canceled because of the war. It was 1948 before Gretchen got her chance to compete in the Olympics at age 29. She made the most of it, winning gold in the women’s slalom and silver in the combined event. She was the first American to win a gold medal in Olympic skiing.

Fraser continued to ski and promote the sport after her triumph. She made a couple of appearances in the movies as a stand-in skier for Sonja Henie in “Thin Ice” and that quintessential Sun Valley movie, “Sun Valley Serenade.” Fraser influenced future Olympians, mentoring Idaho medal winners Christin Cooper and Picabo Street, as well as Idahoan Muffy Davis, who won three gold medals in the Paralympics in 2012.

Gretchen Fraser was born in Tacoma, Washington. She fell in love with Idaho—and fell in love—in 1938 when she came to Sun Valley to compete in the Harriman Cup ski race. She met her future husband, Donald Fraser on the train traveling to Idaho. Donald had been a member of the 1936 US Olympic ski team. The two were married in 1939 and took up residence in Sun Valley. Both became members of the 1940 US Olympic ski team.

The 1940 games were canceled because of the war. It was 1948 before Gretchen got her chance to compete in the Olympics at age 29. She made the most of it, winning gold in the women’s slalom and silver in the combined event. She was the first American to win a gold medal in Olympic skiing.

Fraser continued to ski and promote the sport after her triumph. She made a couple of appearances in the movies as a stand-in skier for Sonja Henie in “Thin Ice” and that quintessential Sun Valley movie, “Sun Valley Serenade.” Fraser influenced future Olympians, mentoring Idaho medal winners Christin Cooper and Picabo Street, as well as Idahoan Muffy Davis, who won three gold medals in the Paralympics in 2012.

Published on May 07, 2023 04:00

May 6, 2023

Basque Radio (Tap to read)

The Basque Museum in Boise tells the fascinating story of the culture and history of a people who have long been an important part of the fabric of our lives in Idaho. There you’ll learn about the role language has played in that history, both in the way it sometimes separated Basques from others in the West and the way it kept the traditions of the community alive.

In 1949 some Basques in Boise thought of a way to send out words and music that would be familiar to sheepherders and other Basques across the spread of the West. They started a weekly radio program on KDSH (later KBOI) broadcast entirely in the Basque language (Euskra). The program featured news of loved ones, such as birthdays, weddings, and births, as well as news of the world, weather, and the latest music from Spain.

The show also aired on KGEM at one time. The photo is of Espe Alegria, the “Voice of the Basques” on KGEM in about 1954. With volunteer announcers, the Basque language program aired for 30 years.

In 1949 some Basques in Boise thought of a way to send out words and music that would be familiar to sheepherders and other Basques across the spread of the West. They started a weekly radio program on KDSH (later KBOI) broadcast entirely in the Basque language (Euskra). The program featured news of loved ones, such as birthdays, weddings, and births, as well as news of the world, weather, and the latest music from Spain.

The show also aired on KGEM at one time. The photo is of Espe Alegria, the “Voice of the Basques” on KGEM in about 1954. With volunteer announcers, the Basque language program aired for 30 years.

Published on May 06, 2023 04:00

May 5, 2023

Idaho Art Deco (Tap to read)

Government buildings are often unimaginative cubes designed with little thought of beauty. Yet, much of Idaho’s most interesting architecture can be found in government buildings. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) was responsible for funding seven county courthouses in Idaho, all within the Art Deco style. Art Deco came into vogue in the US and Europe in the 1920s. The style found its way into architecture, as well as furniture, jewelry, cars, fashion, and everyday objects such as radios. It was a modern style that often infused functional objects from buildings to vacuum cleaners with artistic touches.

The following were all built using WPA funding. All are Art Deco, and all are also on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Boundary County Courthouse in Bonners Ferry was built by the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in 1941. National Register of Historic Places.

The brick Cassia County Courthouse in Burley was built in 1939.

The Franklin County Courthouse in Preston was built in 1939. Hyrum Pope, of Salt Lake City, was the architect. Pope died of a heart attack while on-site inspecting construction of the building.

The Gem County Courthouse in Emmett was designed by Frank Hummel of the Boise firm Tourtellotte and Hummel, and was built in 1938.

The Jefferson County Courthouse in Rigby was built in 1938. Idaho Falls architects Sundberg and Sundberg designed it.

The Jerome County Courthouse in Jerome was built in 1939.

The Oneida County Courthouse in Malad was built in 1938 from plans drawn up by Sundberg and Sundberg.

The Washington County Courthouse in Weiser was designed by Tourtellotte and Hummel, and was built in 1939.

The following were all built using WPA funding. All are Art Deco, and all are also on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Boundary County Courthouse in Bonners Ferry was built by the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in 1941. National Register of Historic Places.

The brick Cassia County Courthouse in Burley was built in 1939.

The Franklin County Courthouse in Preston was built in 1939. Hyrum Pope, of Salt Lake City, was the architect. Pope died of a heart attack while on-site inspecting construction of the building.

The Gem County Courthouse in Emmett was designed by Frank Hummel of the Boise firm Tourtellotte and Hummel, and was built in 1938.

The Jefferson County Courthouse in Rigby was built in 1938. Idaho Falls architects Sundberg and Sundberg designed it.

The Jerome County Courthouse in Jerome was built in 1939.

The Oneida County Courthouse in Malad was built in 1938 from plans drawn up by Sundberg and Sundberg.

The Washington County Courthouse in Weiser was designed by Tourtellotte and Hummel, and was built in 1939.

Published on May 05, 2023 04:00

May 4, 2023

American Falls Dam (Tap to read)

In a previous Speaking of Idaho post about moving the town of American Falls to make way for the rising reservoir behind what would be the American Falls Dam, I had a couple of folks ask if I knew of any pictures of the falls before the dam.

I had wondered what the falls had looked like. Were they spectacular, something akin to Shoshone Falls? No, more akin to Idaho Falls, a drop in the river elevation but not a heart-stopping one.

The photo shows the first power plant located on the falls. It was built in 1902 and acquired by Idaho Power in 1916. An Oregon Shortline train is shown in the background chugging across the railroad bridge. They started building the first dam in 1925 and completed it in 1927. It’s not the dam you can drive across today, though. That was completed in 1978, downstream from the original. That followed a scare in 1976 when the Teton Dam failed. Water managers were afraid the sudden influx from that failure might cause the American Falls Dam to fail, too, sending even more water crashing down the Snake, taking out dams as it went, increasing in volume all the way to the Columbia. To prevent that, they threw open the gates at American Falls, avoiding the potential of an even larger disaster.

Power generation at American Falls is the reason for the name Power County. The current dam churns out 112 megawatts annually.

I had wondered what the falls had looked like. Were they spectacular, something akin to Shoshone Falls? No, more akin to Idaho Falls, a drop in the river elevation but not a heart-stopping one.

The photo shows the first power plant located on the falls. It was built in 1902 and acquired by Idaho Power in 1916. An Oregon Shortline train is shown in the background chugging across the railroad bridge. They started building the first dam in 1925 and completed it in 1927. It’s not the dam you can drive across today, though. That was completed in 1978, downstream from the original. That followed a scare in 1976 when the Teton Dam failed. Water managers were afraid the sudden influx from that failure might cause the American Falls Dam to fail, too, sending even more water crashing down the Snake, taking out dams as it went, increasing in volume all the way to the Columbia. To prevent that, they threw open the gates at American Falls, avoiding the potential of an even larger disaster.

Power generation at American Falls is the reason for the name Power County. The current dam churns out 112 megawatts annually.

Published on May 04, 2023 04:00

May 3, 2023

The New History of Challis Hot Springs (Tap to read)

A little history and a big announcement. First, the history.

Robert Currie Beardsley, born in Woodstock, New Brunswick, Canada, in 1840, had tried his luck at running a sawmill in Montana and mining in California, but he didn’t make a real go of it until he moved to Idaho in 1877. He and two partners, W. A. Norton and J.B. Hood discovered what would become the Beardsley Mine near Bayhorse. The town was so named because an earlier miner who had a couple of bay horses first told of of riches along what would soon become Bayhorse Creek, about 14 miles southwest of Challis.

The Beardsley Mine once said to be the second-largest silver mine in the state, was one of two major operations at Bayhorse. The other was the Ramshorn Mine.

After operating his mine for several years, Robert Beardsley sold his share in the mine for $40,000, setting him up for life. Sadly, it was a short life.

In 1884, Beardsley traveled to New Orleans for the World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition. It was one of the first major world expositions. Think of it as a world fair. Beardsley probably did not go seeking a wife. Nevertheless, he found one.

The New Orleans Times-Democrat reported that on the 18th of February 1886, “another link was forged in the chain that binds Louisiana to the far Northwest. It was a golden link, and took the shape of a marriage between Robert Beardsley, one of the representative men of Idaho Territory—a hard-headed, successful miner—and Miss (Eleanor) Nellie Hallaran, of Magazine Street, a native of this city. Mr. Beardsley met the lady last year while here on a visit to the Exposition. He said nothing but bore away in his Northwestern heart so strong an impress of her image that his return was a matter of necessity.” The newlyweds left the next day, taking a train to Blackfoot, then traveling by stage to Challis.

Though his name is attached to his mine in the history books, Beardsley left a legacy that far outlasted it. He homesteaded on property east of Challis in 1880. The view was gorgeous and the meadows green, but it was the water that attracted Beardsley. It was hot. So hot that horse teams pulling Fresno scrapers to dig the soaking pools had to be changed out every couple of hours to let their hooves cool down.

Known today as Challis Hot Springs, the place was originally the Beardsley Resort and Hotel. Robert Beardsley floated logs down the Salmon from forested hillsides upriver and pulled them out on his property to construct some early buildings. Perhaps this casual, friendly relationship with the river gave him a false sense of confidence.

On June 30, 1888, Beardsley set out to cross the river to his hot springs resort with a team of horses and a wagon. While a handful of people watched, the raging current caught and tumbled the wagon, pulling the team and Beardsley under. Beardsley was sighted for a time in the current, but there was no way to attempt a rescue. You can find his grave on the mountainside above the hot springs today.

Eleanor eventually remarried a man named John Kirk. Eleanor continued to build up the hot springs resort. Ownership eventually passed to Eleanor and Robert Beardsley’s daughter Isabella and her husband John Hammond in 1931. Their son Robert Beardsley Hammond took over the hot springs in 1951. Twenty years later, his son, Robert Charles Hammond, purchased Challis Hot Springs. Bob and his wife Lorna maintained a home on the property until November 2013, when Bob passed away. Their two daughters, Kate Taylor and Mary Elizabeth Conner, managed the property until 2023.

And, now, the announcement. I’m pleased to be joining Lorna Hammond and her family, Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation Director Susan Buxton, and invited guests today in Challis for the dedication of the Challis Hot Springs Unit of Land of the Yankee Fork State Park.

I’ve been among the many people working to make this happen over the past several years. It will be great to see IDPR take over ownership and management of the property to carry on the Hammond Family tradition of welcoming visitors to Challis Hot Springs.

Robert Currie Beardsley

Robert Currie Beardsley

Robert Currie Beardsley, born in Woodstock, New Brunswick, Canada, in 1840, had tried his luck at running a sawmill in Montana and mining in California, but he didn’t make a real go of it until he moved to Idaho in 1877. He and two partners, W. A. Norton and J.B. Hood discovered what would become the Beardsley Mine near Bayhorse. The town was so named because an earlier miner who had a couple of bay horses first told of of riches along what would soon become Bayhorse Creek, about 14 miles southwest of Challis.

The Beardsley Mine once said to be the second-largest silver mine in the state, was one of two major operations at Bayhorse. The other was the Ramshorn Mine.

After operating his mine for several years, Robert Beardsley sold his share in the mine for $40,000, setting him up for life. Sadly, it was a short life.

In 1884, Beardsley traveled to New Orleans for the World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition. It was one of the first major world expositions. Think of it as a world fair. Beardsley probably did not go seeking a wife. Nevertheless, he found one.

The New Orleans Times-Democrat reported that on the 18th of February 1886, “another link was forged in the chain that binds Louisiana to the far Northwest. It was a golden link, and took the shape of a marriage between Robert Beardsley, one of the representative men of Idaho Territory—a hard-headed, successful miner—and Miss (Eleanor) Nellie Hallaran, of Magazine Street, a native of this city. Mr. Beardsley met the lady last year while here on a visit to the Exposition. He said nothing but bore away in his Northwestern heart so strong an impress of her image that his return was a matter of necessity.” The newlyweds left the next day, taking a train to Blackfoot, then traveling by stage to Challis.

Though his name is attached to his mine in the history books, Beardsley left a legacy that far outlasted it. He homesteaded on property east of Challis in 1880. The view was gorgeous and the meadows green, but it was the water that attracted Beardsley. It was hot. So hot that horse teams pulling Fresno scrapers to dig the soaking pools had to be changed out every couple of hours to let their hooves cool down.

Known today as Challis Hot Springs, the place was originally the Beardsley Resort and Hotel. Robert Beardsley floated logs down the Salmon from forested hillsides upriver and pulled them out on his property to construct some early buildings. Perhaps this casual, friendly relationship with the river gave him a false sense of confidence.

On June 30, 1888, Beardsley set out to cross the river to his hot springs resort with a team of horses and a wagon. While a handful of people watched, the raging current caught and tumbled the wagon, pulling the team and Beardsley under. Beardsley was sighted for a time in the current, but there was no way to attempt a rescue. You can find his grave on the mountainside above the hot springs today.

Eleanor eventually remarried a man named John Kirk. Eleanor continued to build up the hot springs resort. Ownership eventually passed to Eleanor and Robert Beardsley’s daughter Isabella and her husband John Hammond in 1931. Their son Robert Beardsley Hammond took over the hot springs in 1951. Twenty years later, his son, Robert Charles Hammond, purchased Challis Hot Springs. Bob and his wife Lorna maintained a home on the property until November 2013, when Bob passed away. Their two daughters, Kate Taylor and Mary Elizabeth Conner, managed the property until 2023.

And, now, the announcement. I’m pleased to be joining Lorna Hammond and her family, Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation Director Susan Buxton, and invited guests today in Challis for the dedication of the Challis Hot Springs Unit of Land of the Yankee Fork State Park.

I’ve been among the many people working to make this happen over the past several years. It will be great to see IDPR take over ownership and management of the property to carry on the Hammond Family tradition of welcoming visitors to Challis Hot Springs.

Robert Currie Beardsley

Robert Currie Beardsley

Published on May 03, 2023 04:00

May 2, 2023

Archie Teater (Tap to read)

Frank Lloyd Wright designed only one home and studio for another artist. Can you guess where it is? Yes, it’s a fair bet the home is in Idaho, given the state-shaped geographical boundaries of this history series. But where in Idaho? Pssst! Say, Hagerman.

Wright designed a home for Archie and Patricia Teater to be built near Hagerman in 1952. The house is perched above the Snake River just north of town. The site is called Teater’s Knoll. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1984. The house is privately owned but occasionally opened for special events. A couple of books are available about the house, Teater’s Knoll: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Idaho Legacy and At Nature’s Edge: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Artist Studio .

But who was Teater? Born in 1901 in Boise, Archie Boyd Teater was a plein-air landscape artist who painted mostly Western scenes. His oils were displayed alongside Frederick Remington, Charles Russell, Thomas Moran, and Thomas Hart Benton. In his youth, he worked alongside miners, trappers, and lumberjacks who probably cared little for Teater’s passion for painting, which would draw him away for days into the mountains, where he would lose himself in the grandeur he meant to capture.

The Teater paintings below are owned by the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation and are on display at agency headquarters in Boise. The top painting is a view of Ritter Island, now a state park unit, from the cliffs above the island. On the bottom is a depiction of what Thousand Springs once looked like from the island itself. A power-generating structure now captures most of the flow of the springs and their once splendid beauty.

Wright designed a home for Archie and Patricia Teater to be built near Hagerman in 1952. The house is perched above the Snake River just north of town. The site is called Teater’s Knoll. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1984. The house is privately owned but occasionally opened for special events. A couple of books are available about the house, Teater’s Knoll: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Idaho Legacy and At Nature’s Edge: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Artist Studio .

But who was Teater? Born in 1901 in Boise, Archie Boyd Teater was a plein-air landscape artist who painted mostly Western scenes. His oils were displayed alongside Frederick Remington, Charles Russell, Thomas Moran, and Thomas Hart Benton. In his youth, he worked alongside miners, trappers, and lumberjacks who probably cared little for Teater’s passion for painting, which would draw him away for days into the mountains, where he would lose himself in the grandeur he meant to capture.

The Teater paintings below are owned by the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation and are on display at agency headquarters in Boise. The top painting is a view of Ritter Island, now a state park unit, from the cliffs above the island. On the bottom is a depiction of what Thousand Springs once looked like from the island itself. A power-generating structure now captures most of the flow of the springs and their once splendid beauty.

Published on May 02, 2023 04:00

May 1, 2023

The Massacre that wasn't (Tap to read)

So, here’s the story, as commemorated on an Idaho-shaped marker in the tiny Idaho town of Almo. “Dedicated to the memory of those who lost their lives in a horrible Indian Massacre, 1861. Three hundred immigrants west bound. Only five escaped. –Erected by S & D of Idaho Pioneers, 1938.”

I’m always a little peeved when someone depicts the shape of Idaho from memory, getting it a little wrong. This monument stretches the state from east to west, giving it a fat panhandle hardly worthy of the name. But that’s the least of the issues with this monument. The number of pioneers killed is a little off. By 300.

The earliest recorded mention of what would have been about the worst massacre ever in the old West was in 1927. That was 66 years after it was supposed to have taken place.

A 1937 article in the Idaho Statesman about the effort to erect a monument at the site noted that, “Idaho’s written histories, for some reason, say little or nothing of the Almo Massacre.”

Esteemed historian Brigham Madsen decided to look into the massacre. Madsen was a meticulous researcher and truth seeker. He checked newspapers of the time, which typically carried every clash between Indians and settlers with practiced sensationalism. Nada. He checked records from the War Department, the Indian Service, and state and territorial records. Zip.

His conclusion was that there was no such incident. So why did the Sons and Daughters of Idaho Pioneers put up the monument? In his opinion, it came about when a couple of area newspapers came up with something called “Exploration Day” in 1938. It was meant to bring tourists to Almo to gawk at City of Rocks, a nearby area of rock pinnacles that stands well enough on its own grandeur, thank you very much, and needs no help from a monument.

The promotion seemed to work, though President Franklin Delano Roosevelt sent his regrets when invited to the unveiling of the monument. In 1939, the Statesman carried a detailed account of the massacre, notably starting with this paragraph: “Public interest in the City of Rocks near Oakley was revived recently by the second official exploration. Efforts to have the area designated as a national monument are progressing.” The detailed account gave practically a blow-by-blow description of the massacre, leaving out only the names of a single person who died there or the names of any of the five survivors.

So where did all the detail about the massacre come from? I found the account in a book called Six Decades Back, by Charles Shirley Walgamott, published first by Caxton in 1936 and republished by University of Idaho Press in 1990. Many of the newspaper accounts are lifted word for word from the book. Walgamott relied on the memory of W.M. E. Johnston who was a 12-year-old living in Ogden, Utah at the time of the alleged massacre. He remembered stories about the event from that time. About a dozen years later he and his family moved to the Almo area and began farming at the massacre site. He claimed they often plowed up old coins, pistols, and other evidence that it had taken place.

Merle Wells and other historians at the Idaho State Historical Society agreed with Madsen that the event never happened, and in the mid-1990s they proposed to take the stone down in the interest of accuracy. The residents of Almo were not at all thrilled with that idea. They had grown up hearing the story of the Almo Massacre. It was part of their cultural fabric. So, the stone stayed in place.

So did the City of Rocks. It should be on your bucket list to see the City of Rocks National Reserve, now jointly managed by the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation and the National Park Service. While you’re there, check out Castle Rocks State Park. Oh, and that monument, if you’re curious.

I’m always a little peeved when someone depicts the shape of Idaho from memory, getting it a little wrong. This monument stretches the state from east to west, giving it a fat panhandle hardly worthy of the name. But that’s the least of the issues with this monument. The number of pioneers killed is a little off. By 300.

The earliest recorded mention of what would have been about the worst massacre ever in the old West was in 1927. That was 66 years after it was supposed to have taken place.

A 1937 article in the Idaho Statesman about the effort to erect a monument at the site noted that, “Idaho’s written histories, for some reason, say little or nothing of the Almo Massacre.”

Esteemed historian Brigham Madsen decided to look into the massacre. Madsen was a meticulous researcher and truth seeker. He checked newspapers of the time, which typically carried every clash between Indians and settlers with practiced sensationalism. Nada. He checked records from the War Department, the Indian Service, and state and territorial records. Zip.

His conclusion was that there was no such incident. So why did the Sons and Daughters of Idaho Pioneers put up the monument? In his opinion, it came about when a couple of area newspapers came up with something called “Exploration Day” in 1938. It was meant to bring tourists to Almo to gawk at City of Rocks, a nearby area of rock pinnacles that stands well enough on its own grandeur, thank you very much, and needs no help from a monument.

The promotion seemed to work, though President Franklin Delano Roosevelt sent his regrets when invited to the unveiling of the monument. In 1939, the Statesman carried a detailed account of the massacre, notably starting with this paragraph: “Public interest in the City of Rocks near Oakley was revived recently by the second official exploration. Efforts to have the area designated as a national monument are progressing.” The detailed account gave practically a blow-by-blow description of the massacre, leaving out only the names of a single person who died there or the names of any of the five survivors.

So where did all the detail about the massacre come from? I found the account in a book called Six Decades Back, by Charles Shirley Walgamott, published first by Caxton in 1936 and republished by University of Idaho Press in 1990. Many of the newspaper accounts are lifted word for word from the book. Walgamott relied on the memory of W.M. E. Johnston who was a 12-year-old living in Ogden, Utah at the time of the alleged massacre. He remembered stories about the event from that time. About a dozen years later he and his family moved to the Almo area and began farming at the massacre site. He claimed they often plowed up old coins, pistols, and other evidence that it had taken place.

Merle Wells and other historians at the Idaho State Historical Society agreed with Madsen that the event never happened, and in the mid-1990s they proposed to take the stone down in the interest of accuracy. The residents of Almo were not at all thrilled with that idea. They had grown up hearing the story of the Almo Massacre. It was part of their cultural fabric. So, the stone stayed in place.

So did the City of Rocks. It should be on your bucket list to see the City of Rocks National Reserve, now jointly managed by the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation and the National Park Service. While you’re there, check out Castle Rocks State Park. Oh, and that monument, if you’re curious.

Published on May 01, 2023 04:00