Rick Just's Blog, page 52

July 30, 2023

The Idaho Falls Post Register Started in Blackfoot

The Post Register is one of Idaho’s more important newspapers, and one with a long history, tracing its roots back to 1880. The newspaper has published in Idaho Falls for most of that time, but it didn’t start out there. It started in Blackfoot, as the Blackfoot Register.

Blackfoot was the terminus of the railroad in 1880 and probably seemed to publisher Edward Wheeler the better bet for starting a newspaper than Eagle Rock, 25 miles to the north. Eagle Rock would later become Idaho Falls, and by far the larger city, but in 1880 it didn’t amount to much. It had a saloon, a store, and Matt Taylor’s toll bridge. Blackfoot, meanwhile, had a café, hotel, four general stores, four saloons, two blacksmith shops, a wagon shop, a lumber yard, a doctor, and even a jewelry store. It was also, at the time, the most populated city in Idaho Territory. Newspapers run on advertising, so starting one in the comparatively booming City of Blackfoot was the easy choice.

And, make no mistake, advertising was top of mind for Mr. Wheeler. In the first edition of the Blackfoot Register he wrote, “We have… one main object in view, and that is to secure as large an amount of the filthy lucre as possible.”

Wheeler did well enough in Blackfoot for the more than three years he operated there. He plunged into local political issues, championed the building of the city’s first school, and even campaigned to make Blackfoot the territory’s new capital. But lucre moved north and so did the paper.

By 1884 the railroad line had stretched to Eagle Rock and established its headquarters there. Settlers began pouring in. Wheeler pulled up stakes and moved his operation to Eagle Rock where the newspaper began calling itself the Idaho Register.

Blackfoot was the terminus of the railroad in 1880 and probably seemed to publisher Edward Wheeler the better bet for starting a newspaper than Eagle Rock, 25 miles to the north. Eagle Rock would later become Idaho Falls, and by far the larger city, but in 1880 it didn’t amount to much. It had a saloon, a store, and Matt Taylor’s toll bridge. Blackfoot, meanwhile, had a café, hotel, four general stores, four saloons, two blacksmith shops, a wagon shop, a lumber yard, a doctor, and even a jewelry store. It was also, at the time, the most populated city in Idaho Territory. Newspapers run on advertising, so starting one in the comparatively booming City of Blackfoot was the easy choice.

And, make no mistake, advertising was top of mind for Mr. Wheeler. In the first edition of the Blackfoot Register he wrote, “We have… one main object in view, and that is to secure as large an amount of the filthy lucre as possible.”

Wheeler did well enough in Blackfoot for the more than three years he operated there. He plunged into local political issues, championed the building of the city’s first school, and even campaigned to make Blackfoot the territory’s new capital. But lucre moved north and so did the paper.

By 1884 the railroad line had stretched to Eagle Rock and established its headquarters there. Settlers began pouring in. Wheeler pulled up stakes and moved his operation to Eagle Rock where the newspaper began calling itself the Idaho Register.

Published on July 30, 2023 04:00

July 29, 2023

Idaho's Two Poet Laureates

I was helping to produce an interpretive handout for use in the historic home once occupied by my great aunt, Agnes Just Reid when the subject of poet laureates came up. She was a well-known writer in the northwest when she was alive. A family member mentioned that she had been the poet laureate of Idaho. I didn’t think so, because it was the kind of thing I would remember. So, that sent me down a poet laureate path.

Poets laureate were frequently mentioned in early newspapers. Most of those stories were about poets in England, where there was a lot of respect for the title because it was bestowed by the royal family. British poets laureate often graced the pages of the Idaho Statesman in the early days. Alfred Austin was a favorite in the 1890s.

The term was loosely thrown around as an honor for those in clubs and organizations where someone would dash off a rhyme from time to time. Often the title was used in jest. The first mention of an Idaho poet laureate was used that way.

On March 25, 1911, the Idaho Statesman ran an article with the headline, Poet Laureate of Idaho is on the Job at State House. “The spring poet may be a joke in some quarters,” the article began, “but he is an actual living, glowing reality in Boise, and with the first warm rain that burst the buds of the trees he blossomed forth and has been busily engaged for the past few days distributing his poems about the statehouse.”

The man was allegedly using the pen name Hask Haskell. No further mention of that name every appeared in the paper again.

But in 1923, it finally happened. Gov. C.C. Moore named Irene Welch Grissom of Idaho Falls Idaho’s first poet laureate. She appeared in stories here and there reading her poems to various groups and releasing new books for many years. Tracking her in a digital search was a little iffy because although everyone seemed to agree on the spelling of her first and last name, her middle name sometimes appeared as Welsh, sometimes Walsh, sometimes Welsch.

Shortly after Idaho named a poet laureate, Wyoming residents decided they needed one. Wyoming Governor W.B. Ross was reluctant to appoint one because he wasn’t sure he had the legal authority. The editor of the Casper Daily Herald was checking into how Idaho had done it, according to a blurb in the Statesman, which quoted Kelly the elevator man at the statehouse as saying, “Now I ask you, what have they in Wyoming to muse about ‘cept rattlesnakes, oil and cows?”

So, snark was alive and well in 1923.

Irene Welch Grissom was apparently expected to serve as Idaho’s poet laureate for life. She did so for many years until she committed a scandalous crime. In 1948 she moved to (gasp!) California.

So, that year, Gov. C.A. Robbins appointed a committee of writers who would nominate a new poet laureate. Agnes Just Reid was on that committee, so that may have been the connection in my cousin’s memory. They recommended, and Gov. Robbins selected, Sudie Stuart Hager of Kimberly as Idaho’s second poet laureate. There was confusion over her middle name in stories, as well. It sometimes appeared as Stewart.

Hager served until her death in 1982.

So, we had two poet laureates. No more. Today, the Idaho Commission on the Arts selects an Idaho Writer in Residence who serves for three years, receiving a modest stipend.

Here’s a list of the Idaho Poets Laureate and Idaho Writers in Residence to date:

Irene Welsh Grissom (1923-1948, poet laureate)

Sudie Stuart Hager (1949-1982, poet laureate)

Ron McFarland (1984-1985) (first person named Writer-in-Residence)

Robert Wrigley (1986-1987)

Eberle Umbach (1988-1989)

Neidy Messer (1990-1991)

Daryl Jones (1992-1993)

Clay Morgan (1994-1995)

Lance Olsen (1996-1998)

Bill Johnson (1999-2000)

Jim Irons (July 2, 2001-2004)

Kim Barnes (April 2004-2006)

Anthony "Tony" Doerr (July 2007-July 2010)

Brady Udall (July 1, 2010-June 20, 2013)

Dianne Raptosh, (July 2013-June 2016)

Christian Winn (July 2016 to June 2019)

Malia Collins (July 2019 to June 2020)

CMarie Fuhrman (2021-2023)

Kerri Webster (2024-2026)

Poets laureate were frequently mentioned in early newspapers. Most of those stories were about poets in England, where there was a lot of respect for the title because it was bestowed by the royal family. British poets laureate often graced the pages of the Idaho Statesman in the early days. Alfred Austin was a favorite in the 1890s.

The term was loosely thrown around as an honor for those in clubs and organizations where someone would dash off a rhyme from time to time. Often the title was used in jest. The first mention of an Idaho poet laureate was used that way.

On March 25, 1911, the Idaho Statesman ran an article with the headline, Poet Laureate of Idaho is on the Job at State House. “The spring poet may be a joke in some quarters,” the article began, “but he is an actual living, glowing reality in Boise, and with the first warm rain that burst the buds of the trees he blossomed forth and has been busily engaged for the past few days distributing his poems about the statehouse.”

The man was allegedly using the pen name Hask Haskell. No further mention of that name every appeared in the paper again.

But in 1923, it finally happened. Gov. C.C. Moore named Irene Welch Grissom of Idaho Falls Idaho’s first poet laureate. She appeared in stories here and there reading her poems to various groups and releasing new books for many years. Tracking her in a digital search was a little iffy because although everyone seemed to agree on the spelling of her first and last name, her middle name sometimes appeared as Welsh, sometimes Walsh, sometimes Welsch.

Shortly after Idaho named a poet laureate, Wyoming residents decided they needed one. Wyoming Governor W.B. Ross was reluctant to appoint one because he wasn’t sure he had the legal authority. The editor of the Casper Daily Herald was checking into how Idaho had done it, according to a blurb in the Statesman, which quoted Kelly the elevator man at the statehouse as saying, “Now I ask you, what have they in Wyoming to muse about ‘cept rattlesnakes, oil and cows?”

So, snark was alive and well in 1923.

Irene Welch Grissom was apparently expected to serve as Idaho’s poet laureate for life. She did so for many years until she committed a scandalous crime. In 1948 she moved to (gasp!) California.

So, that year, Gov. C.A. Robbins appointed a committee of writers who would nominate a new poet laureate. Agnes Just Reid was on that committee, so that may have been the connection in my cousin’s memory. They recommended, and Gov. Robbins selected, Sudie Stuart Hager of Kimberly as Idaho’s second poet laureate. There was confusion over her middle name in stories, as well. It sometimes appeared as Stewart.

Hager served until her death in 1982.

So, we had two poet laureates. No more. Today, the Idaho Commission on the Arts selects an Idaho Writer in Residence who serves for three years, receiving a modest stipend.

Here’s a list of the Idaho Poets Laureate and Idaho Writers in Residence to date:

Irene Welsh Grissom (1923-1948, poet laureate)

Sudie Stuart Hager (1949-1982, poet laureate)

Ron McFarland (1984-1985) (first person named Writer-in-Residence)

Robert Wrigley (1986-1987)

Eberle Umbach (1988-1989)

Neidy Messer (1990-1991)

Daryl Jones (1992-1993)

Clay Morgan (1994-1995)

Lance Olsen (1996-1998)

Bill Johnson (1999-2000)

Jim Irons (July 2, 2001-2004)

Kim Barnes (April 2004-2006)

Anthony "Tony" Doerr (July 2007-July 2010)

Brady Udall (July 1, 2010-June 20, 2013)

Dianne Raptosh, (July 2013-June 2016)

Christian Winn (July 2016 to June 2019)

Malia Collins (July 2019 to June 2020)

CMarie Fuhrman (2021-2023)

Kerri Webster (2024-2026)

Published on July 29, 2023 04:00

July 28, 2023

Idaho's Oakley Stone

If you’ve seen a few fireplaces in Idaho, you’ve likely seen Oakley Stone. Beginning in the late 1940s the rock mined nearly Oakley, Idaho in the Albion Mountains became a popular building material for entryways, home veneers, and fireplaces. Geologists know it as micaceous quartzite or Idaho quartzite. Oakley Stone is a trade name.

Oakley stone is popular in the U.S., Canada, and even in Europe, because of its range of colors, from silver to gold and everything in between, but also because it is efficient. It can be split much thinner than competing rock from other quarries. A ton of Oakley Stone can cover 250 to 300 feet, while a ton of other stone veneers can cover 60 feet or less.

Oakley Stone was formed over the ages when layers of clay alternating with layers rich in quartz, compressed together. According to Terry Maley’s book, Exploring Idaho Geology , the alternating quartz-rich layers were flattened by the pressure so that the porosity of the material was removed and the quartz grains formed an interlocking mosaic.

The quarries for the stone are about halfway up Middle Mountain where they can dig through a shallow layer of dirt to access the tilted layers of sedimentary rock. It’s mostly hand work, chiseling along the front edge of the rock to break away plates as thin as a quarter inch and up to 4 inches thick. The plates can be as big as eight feet in diameter, but are usually broken into much smaller pieces. Once on site, the stone is easy to work and shape.

Frank Lloyd Wright specified the stone for the interior and exterior of Teater’s Knoll, near Hagerman. The home was built for artist Archie Teater and is the only one in Idaho designed for a particular site by the famous architect. The photo, courtesy of Henry Whiting, shows Kent Hale’s exterior rock work on the building.

Oakley stone is popular in the U.S., Canada, and even in Europe, because of its range of colors, from silver to gold and everything in between, but also because it is efficient. It can be split much thinner than competing rock from other quarries. A ton of Oakley Stone can cover 250 to 300 feet, while a ton of other stone veneers can cover 60 feet or less.

Oakley Stone was formed over the ages when layers of clay alternating with layers rich in quartz, compressed together. According to Terry Maley’s book, Exploring Idaho Geology , the alternating quartz-rich layers were flattened by the pressure so that the porosity of the material was removed and the quartz grains formed an interlocking mosaic.

The quarries for the stone are about halfway up Middle Mountain where they can dig through a shallow layer of dirt to access the tilted layers of sedimentary rock. It’s mostly hand work, chiseling along the front edge of the rock to break away plates as thin as a quarter inch and up to 4 inches thick. The plates can be as big as eight feet in diameter, but are usually broken into much smaller pieces. Once on site, the stone is easy to work and shape.

Frank Lloyd Wright specified the stone for the interior and exterior of Teater’s Knoll, near Hagerman. The home was built for artist Archie Teater and is the only one in Idaho designed for a particular site by the famous architect. The photo, courtesy of Henry Whiting, shows Kent Hale’s exterior rock work on the building.

Published on July 28, 2023 04:00

July 27, 2023

Where Melon Gravel Came from

One of our most popular posts was about the Stinker Station signs that once dotted the landscape in southern Idaho. The one everyone seems to remember said, “Petrified watermelons. Take one home to your mother-in-law.” Those melons were actually rocks, and if a few people followed the sign’s advice, no one cared. There were plenty of them.

So, what is melon gravel? It’s a common type of rock found from about Massacre Rocks State Park to the Oregon border. It is known for its shape more than its composition. Most melon gravel is basaltic rock that was torn away from the Snake River Canyon walls and lava flows during the Bonneville Flood some 15,000 years ago. The flood carried that rock along for miles, tumbling it against other rocks, knocking off the edges, until it began to round and become relatively smooth.

The gravel ranges in size from, well, a melon, to an SUV. In places, you can find deposits of it a mile wide and a mile and a half long. Many fields in the Magic Valley have piles of the rock that has been scooped up over the years to make way for crops.

For more about the Bonneville Flood, check Terry Maley’s book, Exploring Idaho Geology . For more Farris Lind and his Stinker Station signs, order a copy of my book, Fearless through the handy link on this page.

So, what is melon gravel? It’s a common type of rock found from about Massacre Rocks State Park to the Oregon border. It is known for its shape more than its composition. Most melon gravel is basaltic rock that was torn away from the Snake River Canyon walls and lava flows during the Bonneville Flood some 15,000 years ago. The flood carried that rock along for miles, tumbling it against other rocks, knocking off the edges, until it began to round and become relatively smooth.

The gravel ranges in size from, well, a melon, to an SUV. In places, you can find deposits of it a mile wide and a mile and a half long. Many fields in the Magic Valley have piles of the rock that has been scooped up over the years to make way for crops.

For more about the Bonneville Flood, check Terry Maley’s book, Exploring Idaho Geology . For more Farris Lind and his Stinker Station signs, order a copy of my book, Fearless through the handy link on this page.

Published on July 27, 2023 04:00

July 26, 2023

The Famous Spiral Highway

The Lewiston Hill road is an engineering marvel. Today it’s a four-lane, divided highway that allows drivers to zip up and down the road at 65 mph, hardly noticing the hill at all, unless you’re driving a truck. That wasn’t the case in 1915.

The Lewiston Spiral Highway was a huge project for the Idaho State Highway Commission in 1915 and 1916. It sucked up so much of the highway fund other parts of the state complained bitterly. But what a project. The road was to start in the valley at 725 feet above sea level, and top the hill above the city at 2,750 feet. That’s less than half a mile, as the crow flies, but Model T’s did not fly. The twisting road would run ten miles forth and back, and back and forth, testing many radiators in the climb.

An article in the September 27, 1916 edition of the Lewiston Morning Tribune reported that “Within just two and six tenths miles of the goal—which is the summit of Lewiston Hill—the big Marion Caterpillar steam shovel is still trembling with willing energy, still digging, still climbing, still creeping out of the valley over its own triumphant trail—a trail destined in time to become one of the noted scenic highways of the west.”

The Spiral Highway, sometimes called Uniontown Hill Road, cost the state and the Lewiston highway district $141,587. Oh, and 42 cents.

There was much demand for the new highway. According to a story in the January 12, 1918, edition of the Idaho Statesman “an actual count made by a man stationed at the Eighteenth street bridge” recorded 1280 cars climbing the hill on a single November day. The same article noted that you could see the Blue Mountains in Oregon to the southwest from the top of the hill.

Safety was a big concern. The Statesman article put everyone’s fears to rest. “The right-of-way has been fenced on both sides for the entire distance. Guarding railings, made of frame material with heavy posts were constructed at exposed points on the grade. Barbed wire was used for the balance of the distance. Both the guarding fencing and the wire are set in far enough on the highway to serve as a guide to autoists going over the road on the darkest nights.”

Oh, blessed barbed wire guiding our nighttime autoists!

By the way, the Spiral Highway was the inspiration for a famous rock song.

The Lewiston Spiral Highway was a huge project for the Idaho State Highway Commission in 1915 and 1916. It sucked up so much of the highway fund other parts of the state complained bitterly. But what a project. The road was to start in the valley at 725 feet above sea level, and top the hill above the city at 2,750 feet. That’s less than half a mile, as the crow flies, but Model T’s did not fly. The twisting road would run ten miles forth and back, and back and forth, testing many radiators in the climb.

An article in the September 27, 1916 edition of the Lewiston Morning Tribune reported that “Within just two and six tenths miles of the goal—which is the summit of Lewiston Hill—the big Marion Caterpillar steam shovel is still trembling with willing energy, still digging, still climbing, still creeping out of the valley over its own triumphant trail—a trail destined in time to become one of the noted scenic highways of the west.”

The Spiral Highway, sometimes called Uniontown Hill Road, cost the state and the Lewiston highway district $141,587. Oh, and 42 cents.

There was much demand for the new highway. According to a story in the January 12, 1918, edition of the Idaho Statesman “an actual count made by a man stationed at the Eighteenth street bridge” recorded 1280 cars climbing the hill on a single November day. The same article noted that you could see the Blue Mountains in Oregon to the southwest from the top of the hill.

Safety was a big concern. The Statesman article put everyone’s fears to rest. “The right-of-way has been fenced on both sides for the entire distance. Guarding railings, made of frame material with heavy posts were constructed at exposed points on the grade. Barbed wire was used for the balance of the distance. Both the guarding fencing and the wire are set in far enough on the highway to serve as a guide to autoists going over the road on the darkest nights.”

Oh, blessed barbed wire guiding our nighttime autoists!

By the way, the Spiral Highway was the inspiration for a famous rock song.

Published on July 26, 2023 04:00

July 25, 2023

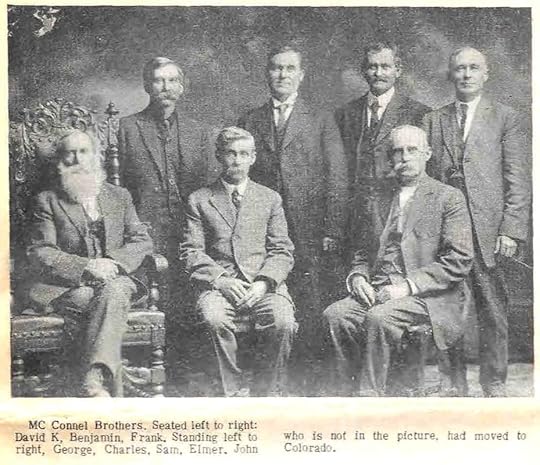

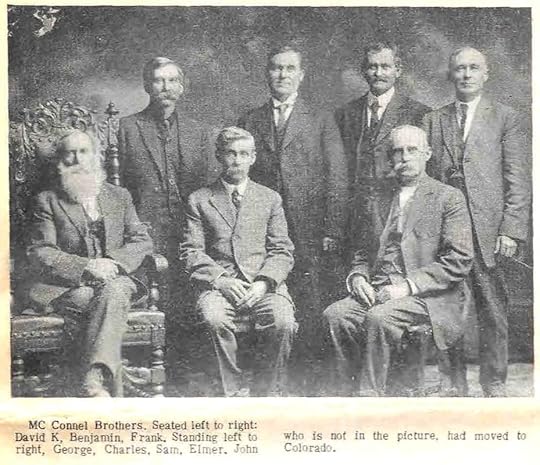

McConnel Island Disappeared

If you do a Google search for McConnel Island, you’ll come up with a couple of near matches, one for the McConnel Islands, plural, near Antarctica, and one for McConnell Island (note the second L) in the San Jaun Islands in Washington State.

If you’re looking for McConnel Island in Idaho, you’ll have to dig a little deeper. Ask around when you’re in Parma.

In the early days of settlement in that area the Boise River formed a delta, with two channels, one to the north and one to the south, forming a 4000-acre island. In 1865, David McConnel claimed land on the island and built a home there as a squatter. In 1879 he applied for and received a homestead claim of an additional 160 acres, bringing his ranch to about 500 acres. Other families, including that of David’s brother, Ben, lived there, and it even had a McConnel Island School.

David McConnel had come West in 1862 with a large Oregon Trail wagon train. He acted as a scout for that train. McConnel had 11 siblings, 10 brothers and a sister. Eight of his brothers followed him to the Boise Valley from their home in Iowa.

McConnel was a vigilante. That word has a negative note to it today, but it was a point of pride for him. It was the beginning of law and order in the area. In writing about his grandfather, Carl Isenberg recalled McConnel saying that “until the committee was formed and operated on several of the rustlers, murderers, etc., no one could feel secure, but that after a few examples, property and individual safety was secure.”

The island became McConnel Island because of David McConnel’s association with it. It ceased being an island when the Ross Fill was built to block off the southern channel of the river to help solve a frequent flooding problem.

Thanks to Merv McConnel for supplying much of the information used for this story.

If you’re looking for McConnel Island in Idaho, you’ll have to dig a little deeper. Ask around when you’re in Parma.

In the early days of settlement in that area the Boise River formed a delta, with two channels, one to the north and one to the south, forming a 4000-acre island. In 1865, David McConnel claimed land on the island and built a home there as a squatter. In 1879 he applied for and received a homestead claim of an additional 160 acres, bringing his ranch to about 500 acres. Other families, including that of David’s brother, Ben, lived there, and it even had a McConnel Island School.

David McConnel had come West in 1862 with a large Oregon Trail wagon train. He acted as a scout for that train. McConnel had 11 siblings, 10 brothers and a sister. Eight of his brothers followed him to the Boise Valley from their home in Iowa.

McConnel was a vigilante. That word has a negative note to it today, but it was a point of pride for him. It was the beginning of law and order in the area. In writing about his grandfather, Carl Isenberg recalled McConnel saying that “until the committee was formed and operated on several of the rustlers, murderers, etc., no one could feel secure, but that after a few examples, property and individual safety was secure.”

The island became McConnel Island because of David McConnel’s association with it. It ceased being an island when the Ross Fill was built to block off the southern channel of the river to help solve a frequent flooding problem.

Thanks to Merv McConnel for supplying much of the information used for this story.

Published on July 25, 2023 04:00

July 24, 2023

The Grand Lady of the Lakes

I’d seen this picture, from the Idaho State Historical Society Digital Collection, many times over the years but missed one interesting detail until recently. It’s the steamboat Georgie Oakes docked at Mission Landing near the Cataldo Mission of the Sacred Heart. The picture was taken around 1891.

Mission Landing was as far up the Coeur d’Alene River as you could get with a big boat. Supplies for the mines were off-loaded here onto a narrow-gauge railway (just visible in the lower right) that took them to the Coeur d’Alene Mining District, Kellogg, Wallace, and Murray. Ore went the other direction, down the railway to the landing and by boat from there.

What I hadn’t noticed before, until I read the picture description furnished by the Idaho State Historical Society, was that the “dock” the Georgie Oakes is tied up to is the cannibalized hull of the steamer Coeur d’Alene, the boat it replaced on the river.

Today we have a romanticized view of those often-elegant looking boats that plied the waters of Lake Coeur d’Alene, and the Coeur d’Alene and St. Joe rivers. In their day, they were working boats that held little charm for most people. None of the many steamers that worked the waters are around still today. No one bothered to save even one. Most burned accidentally, or were scuttled. One went down as the center point of the Fourth of July celebration in 1927. People looked on while the burning boat sank into the lake, sputtering and smoking until it was only a memory. That was the fate of the grand lady of the lakes, the Georgie Oakes.

Mission Landing was as far up the Coeur d’Alene River as you could get with a big boat. Supplies for the mines were off-loaded here onto a narrow-gauge railway (just visible in the lower right) that took them to the Coeur d’Alene Mining District, Kellogg, Wallace, and Murray. Ore went the other direction, down the railway to the landing and by boat from there.

What I hadn’t noticed before, until I read the picture description furnished by the Idaho State Historical Society, was that the “dock” the Georgie Oakes is tied up to is the cannibalized hull of the steamer Coeur d’Alene, the boat it replaced on the river.

Today we have a romanticized view of those often-elegant looking boats that plied the waters of Lake Coeur d’Alene, and the Coeur d’Alene and St. Joe rivers. In their day, they were working boats that held little charm for most people. None of the many steamers that worked the waters are around still today. No one bothered to save even one. Most burned accidentally, or were scuttled. One went down as the center point of the Fourth of July celebration in 1927. People looked on while the burning boat sank into the lake, sputtering and smoking until it was only a memory. That was the fate of the grand lady of the lakes, the Georgie Oakes.

Published on July 24, 2023 04:00

July 23, 2023

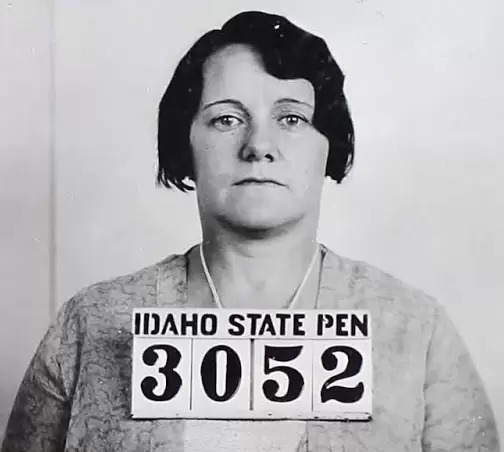

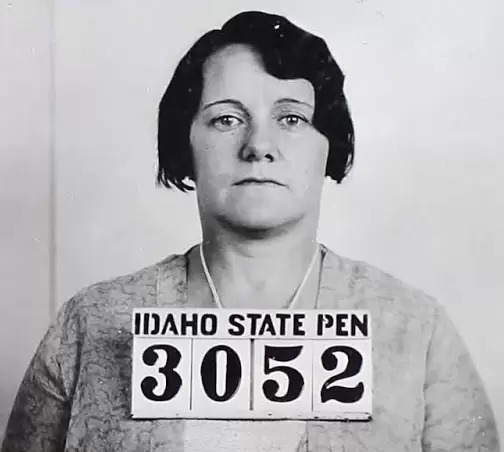

Having Tea with Lady Bluebeard

Infamy was Lyda Southard’s cup of tea. Don’t drink that tea! Southard, who had more names than a centipede has feet, caught one she didn’t seek: Lady Bluebeard.

The country’s first widely known female serial killer, Lyda, wasn’t born in Idaho. Her birthplace—in 1892—was a little town in Missouri. Her family moved to the Twin Falls area when she was a teenager.

Though she came from a poor family, Lyda found a way to make a good living. She worked in insurance.

Lyda collected husbands. She married Robert Dooley in 1912. They lived with Robert’s bachelor brother, Ed, on a farm near Twin Falls. The Dooleys had a daughter, Loraine (some accounts say Laura), in 1914.

In 1915, Lyda collected insurance money after the tragic deaths of her first husband, Robert, their daughter, and Robert’s brother, Ed. The deaths were chalked up to dirty well water, typhoid fever, and ptomaine poisoning, respectively.

Lyda was a looker, by some accounts. Her prison photo may not reflect that, but who looks good in their mugshot? She used her charms to marry another man in 1917, William G. McHaffle. McHaffle had a three-year-old daughter, but not for long. The daughter died shortly after they married. The newlyweds moved to Montana, where, in 1918, Mr. McHaffle, doubly unlucky, died of influenza and diphtheria. Lyda, always practical, collected the insurance money.

Then she got married again. She waited a respectful nearly five months before hitching to Harlan C. Lewis, an automobile salesman from Billings. Lewis lasted four months. He died from complications related to gastroenteritis.

It was just over a year before Lyda found her fourth husband, Edward F. Meyer, a ranch foreman from Twin Falls. Tragedy struck again, this time just a few weeks after the marriage when Meyer died from Typhoid. He did not go easily. A nurse noted how concerned Lyda was about his health and that she always seemed to be giving him sips of water. Alas, the water didn’t save him. The insurance payout this time was $12,000.

The coincidences surrounding this woman so unlucky in love began to raise the suspicions of Twin Falls Chemist Earl Dooley. The Dooley name was not a coincidence. The chemist was a relative of Lyda’s first husband. He pressed for an investigation. Said investigation found evidence of arsenic poisoning in the bodies of Lyda’s hapless husbands and in the cookware she had regularly used. They also found a large supply of flypaper in the basement of a house where she had lived. Flypaper at that time was coated with arsenic.

Meanwhile, Lyda wasn’t sitting still. A few weeks after Meyer’s death, she snagged Paul Southard. The Navy man resisted her insistence on buying life insurance, telling her the Navy would provide for her in the event of his death.

The happy couple was living in Honolulu when police came knocking. Paul Southard insisted that Lyda, his love, was innocent. After all, he’d known her well for several weeks.

When newspapers got wind of the charges against Lyda, they generated headlines about the “temptress,” the “Black Widow,” and the “Lady Bluebeard.” They followed every word in her seven-week trial.

The evidence against Lyda was circumstantial, but there was a ton of it. The jury was reluctant to sentence a pretty 29-year-old woman to death. They convicted her of second-degree murder. She got 10 years.

Ten years in prison kept Lyda off the husband track. Mostly. In 1931 she escaped with a prison trusty, David Minton, who had been released two weeks earlier. Lyda climbed out of her cell courtesy of a handmade rope and a rose trellis.

Authorities found Minton a few months later in Denver. He denied any connection to Lyda, but they soon picked up the trail. She was also in Denver, working as a housekeeper. She already had her clutches on a new man, Harry Whitlock. He was a bit more cautious than Lyda’s previous husbands. Whitlock flatly refused to let her take out a $20,000 insurance policy on him. He wasn’t surprised when the police showed up. Lyda, meanwhile, had skipped town.

Police caught up with Lyda in Kansas 15 months after her escape. She went back to prison in Idaho for another 10 years. Lyda was released in 1941 and pardoned in 1943.

Lyda’s movements after her release are a little sketchy. Eventually, she moved to Provo, Utah, and started a second-hand store. She also started her seventh marriage to a man named Hal Shaw. Shaw’s adult children found out who Lyda was. A divorce soon followed.

Lyda Shaw was the name chiseled onto her headstone in the Twin Falls cemetery. She had the last names of Trueblood, Dooley, McHaffie, Lewis, Meyer, Southard, and Whitlock. She’s most often remembered as Lyda Southard, since that’s the name she was using when she first entered prison. Lyda was sometimes Lydia on official records. Whatever you call her, she earned the title of murderess.

The country’s first widely known female serial killer, Lyda, wasn’t born in Idaho. Her birthplace—in 1892—was a little town in Missouri. Her family moved to the Twin Falls area when she was a teenager.

Though she came from a poor family, Lyda found a way to make a good living. She worked in insurance.

Lyda collected husbands. She married Robert Dooley in 1912. They lived with Robert’s bachelor brother, Ed, on a farm near Twin Falls. The Dooleys had a daughter, Loraine (some accounts say Laura), in 1914.

In 1915, Lyda collected insurance money after the tragic deaths of her first husband, Robert, their daughter, and Robert’s brother, Ed. The deaths were chalked up to dirty well water, typhoid fever, and ptomaine poisoning, respectively.

Lyda was a looker, by some accounts. Her prison photo may not reflect that, but who looks good in their mugshot? She used her charms to marry another man in 1917, William G. McHaffle. McHaffle had a three-year-old daughter, but not for long. The daughter died shortly after they married. The newlyweds moved to Montana, where, in 1918, Mr. McHaffle, doubly unlucky, died of influenza and diphtheria. Lyda, always practical, collected the insurance money.

Then she got married again. She waited a respectful nearly five months before hitching to Harlan C. Lewis, an automobile salesman from Billings. Lewis lasted four months. He died from complications related to gastroenteritis.

It was just over a year before Lyda found her fourth husband, Edward F. Meyer, a ranch foreman from Twin Falls. Tragedy struck again, this time just a few weeks after the marriage when Meyer died from Typhoid. He did not go easily. A nurse noted how concerned Lyda was about his health and that she always seemed to be giving him sips of water. Alas, the water didn’t save him. The insurance payout this time was $12,000.

The coincidences surrounding this woman so unlucky in love began to raise the suspicions of Twin Falls Chemist Earl Dooley. The Dooley name was not a coincidence. The chemist was a relative of Lyda’s first husband. He pressed for an investigation. Said investigation found evidence of arsenic poisoning in the bodies of Lyda’s hapless husbands and in the cookware she had regularly used. They also found a large supply of flypaper in the basement of a house where she had lived. Flypaper at that time was coated with arsenic.

Meanwhile, Lyda wasn’t sitting still. A few weeks after Meyer’s death, she snagged Paul Southard. The Navy man resisted her insistence on buying life insurance, telling her the Navy would provide for her in the event of his death.

The happy couple was living in Honolulu when police came knocking. Paul Southard insisted that Lyda, his love, was innocent. After all, he’d known her well for several weeks.

When newspapers got wind of the charges against Lyda, they generated headlines about the “temptress,” the “Black Widow,” and the “Lady Bluebeard.” They followed every word in her seven-week trial.

The evidence against Lyda was circumstantial, but there was a ton of it. The jury was reluctant to sentence a pretty 29-year-old woman to death. They convicted her of second-degree murder. She got 10 years.

Ten years in prison kept Lyda off the husband track. Mostly. In 1931 she escaped with a prison trusty, David Minton, who had been released two weeks earlier. Lyda climbed out of her cell courtesy of a handmade rope and a rose trellis.

Authorities found Minton a few months later in Denver. He denied any connection to Lyda, but they soon picked up the trail. She was also in Denver, working as a housekeeper. She already had her clutches on a new man, Harry Whitlock. He was a bit more cautious than Lyda’s previous husbands. Whitlock flatly refused to let her take out a $20,000 insurance policy on him. He wasn’t surprised when the police showed up. Lyda, meanwhile, had skipped town.

Police caught up with Lyda in Kansas 15 months after her escape. She went back to prison in Idaho for another 10 years. Lyda was released in 1941 and pardoned in 1943.

Lyda’s movements after her release are a little sketchy. Eventually, she moved to Provo, Utah, and started a second-hand store. She also started her seventh marriage to a man named Hal Shaw. Shaw’s adult children found out who Lyda was. A divorce soon followed.

Lyda Shaw was the name chiseled onto her headstone in the Twin Falls cemetery. She had the last names of Trueblood, Dooley, McHaffie, Lewis, Meyer, Southard, and Whitlock. She’s most often remembered as Lyda Southard, since that’s the name she was using when she first entered prison. Lyda was sometimes Lydia on official records. Whatever you call her, she earned the title of murderess.

Published on July 23, 2023 04:00

July 22, 2023

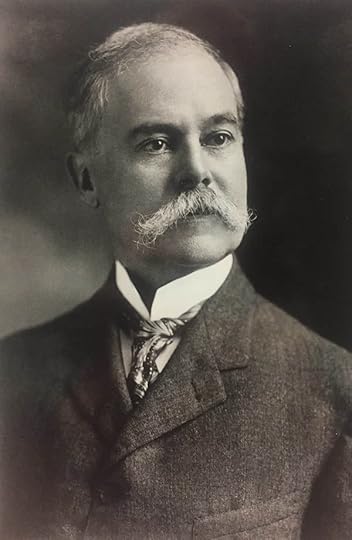

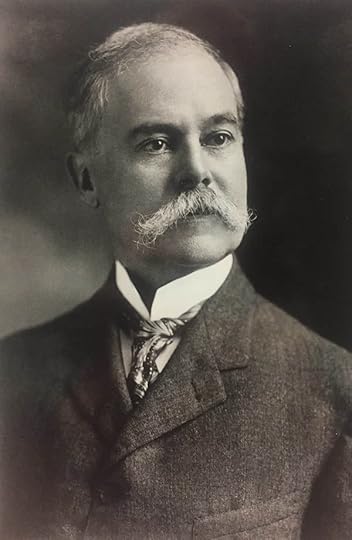

Such a Kind Looking Man

In 1882, Fred T. Dubois might be found crawling beneath a house searching for a secret compartment where a polygamist was hiding. In 1887 he could be found in Congress, representing Idaho Territory. There was a solid link between the two activities.

Fred Dubois came to Idaho Territory in 1880 with his brother Dr. Jesse Dubois, Jr, who had been appointed physician at the Fort Hall Indian Agency. The younger Dubois—Fred was only 29—spent a few months as a cattle drive cowboy before he got into his preferred career, politics. The Dubois brothers grew up in Illinois. Their parents were friends with Abraham Lincoln. So, Fred Dubois had political connections in Washington, D.C. That smoothed the way for him to become U.S. Marshall for Idaho Territory, a position for which he had no discernable qualifications.

Nevertheless, he embraced the job, especially when it came to arresting Mormon polygamists. He was frustrated, though, because juries of their peers routinely set the polygamists free.

Dubois pushed to get a bill passed in the territorial legislature that would allow him to bring men with multiple wives to justice, even though polygamy was already illegal under federal law. The result was the “test oath.” Under the terms of the law territorial officials could require an oath of nonsupport of “celestial marriage” before a person could vote, hold office, or serve on a jury. Suddenly a jury of a polygamist’s peers could not include members of the LDS faith. The prohibition was soon ensconced in the Idaho constitution. It was enforced for only a few years, but remained in the constitution until 1982.

It wasn’t polygamy itself that Dubois abhorred, or the Mormon faith. It was the political power of Mormons he wanted to quell. They tended to vote in a block. In 1880, for instance, every vote in Bear Lake County was for a Democrat.

Politics was very much Fred T. Dubois’ game. He became popular with non-Mormons statewide, and since Mormons could no longer vote, he easily won election as a territorial delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1887. He was elected to the Senate after Idaho became a state, serving from 1901 to 1907.

Thanks to Randy Stapilus for his book Jerks in Idaho History , and Deana Lowe Jensen for her book about Fred T. Dubois, Let the Eagle Scream . I depended heavily on both for this post.

Fred Dubois came to Idaho Territory in 1880 with his brother Dr. Jesse Dubois, Jr, who had been appointed physician at the Fort Hall Indian Agency. The younger Dubois—Fred was only 29—spent a few months as a cattle drive cowboy before he got into his preferred career, politics. The Dubois brothers grew up in Illinois. Their parents were friends with Abraham Lincoln. So, Fred Dubois had political connections in Washington, D.C. That smoothed the way for him to become U.S. Marshall for Idaho Territory, a position for which he had no discernable qualifications.

Nevertheless, he embraced the job, especially when it came to arresting Mormon polygamists. He was frustrated, though, because juries of their peers routinely set the polygamists free.

Dubois pushed to get a bill passed in the territorial legislature that would allow him to bring men with multiple wives to justice, even though polygamy was already illegal under federal law. The result was the “test oath.” Under the terms of the law territorial officials could require an oath of nonsupport of “celestial marriage” before a person could vote, hold office, or serve on a jury. Suddenly a jury of a polygamist’s peers could not include members of the LDS faith. The prohibition was soon ensconced in the Idaho constitution. It was enforced for only a few years, but remained in the constitution until 1982.

It wasn’t polygamy itself that Dubois abhorred, or the Mormon faith. It was the political power of Mormons he wanted to quell. They tended to vote in a block. In 1880, for instance, every vote in Bear Lake County was for a Democrat.

Politics was very much Fred T. Dubois’ game. He became popular with non-Mormons statewide, and since Mormons could no longer vote, he easily won election as a territorial delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1887. He was elected to the Senate after Idaho became a state, serving from 1901 to 1907.

Thanks to Randy Stapilus for his book Jerks in Idaho History , and Deana Lowe Jensen for her book about Fred T. Dubois, Let the Eagle Scream . I depended heavily on both for this post.

Published on July 22, 2023 04:00

July 21, 2023

Slot Machines were the Cause of Idaho's Foot-Wide Towns

In the August 20, 1951 edition of Life Magazine there was an article entitled, “Idaho’s Foot-Wide Towns.” The article listed the towns of Banks, Garden City, Island Park, Batise, Chubbuck, Atomic City, and Island Park as examples of same. Crouch was the “foot-wide” town most prevalently featured, population 125, and 10 miles long.

These were the towns exploiting a loophole in state law that allowed slot machines in any incorporated town of 125. That encouraged 17 villages along state highways to incorporate by stretching their boundaries up and down the highway, ballooning out here and there, until they snagged 125 people into their city limits. It was gerrymandering for a different cause.

Several of the featured towns, such as Garden City, didn’t much fit the “foot-wide” definition, though Garden City was created to take advantage of the fact that Boise had voted slot machines out.

The January 18, 1951, edition of the Idaho Statesman featured an article about the controversy over slot machines. It quoted a Fremont County legislator as saying 95 percent of Island Park’s income came “from tourists who like to play slot machines.”

Island Park, which has sometimes boasted that it has the longest Main Street in the country at 33 miles long, didn’t quite fit the foot-wide claim in Life Magazine. Its boundaries are 40 or 50 feet wide at the narrowest.

The Idaho Legislature outlawed slot machines in 1953, but some skinny towns such as Island Park retained their incorporation, so they could serve liquor by the drink, also made possible by the aforementioned loophole.

These were the towns exploiting a loophole in state law that allowed slot machines in any incorporated town of 125. That encouraged 17 villages along state highways to incorporate by stretching their boundaries up and down the highway, ballooning out here and there, until they snagged 125 people into their city limits. It was gerrymandering for a different cause.

Several of the featured towns, such as Garden City, didn’t much fit the “foot-wide” definition, though Garden City was created to take advantage of the fact that Boise had voted slot machines out.

The January 18, 1951, edition of the Idaho Statesman featured an article about the controversy over slot machines. It quoted a Fremont County legislator as saying 95 percent of Island Park’s income came “from tourists who like to play slot machines.”

Island Park, which has sometimes boasted that it has the longest Main Street in the country at 33 miles long, didn’t quite fit the foot-wide claim in Life Magazine. Its boundaries are 40 or 50 feet wide at the narrowest.

The Idaho Legislature outlawed slot machines in 1953, but some skinny towns such as Island Park retained their incorporation, so they could serve liquor by the drink, also made possible by the aforementioned loophole.

Published on July 21, 2023 04:00