Rick Just's Blog, page 48

September 8, 2023

Rock Cairns in Idaho

You’ve probably seen a rock cairn somewhere in your travels. People with an artistic bent often leave little stacks of rock in or alongside riverbeds, a tribute to their balancing abilities.

Just don’t. Artistic as your stones may be, they are a distraction from the natural beauty people have come to see. Moving rocks around disturbs micro-ecosystems, often killing creepy crawly critters that might not be on anyone’s list of favorite animals, but are an important part of nature. If you must stack, do it in your yard. End of editorial.

Stone cairns are common on all continents. Stacking rocks is an ancient way to mark things. They may be memorial markers, markers to locate caches, and in later years, property markers on the corner of lots.

In Idaho, Basque sheepherders made stone cairns to mark trails or just to pass the time. They are called “harrimutilak’ or stone boys. They could be over six feet tall. I remember one at the top of Garden Creek Peak in Bingham County when I was a kid. It may not have been a Basque cairn, since it was on the Fort Hall Reservation, but I remember my dad calling it a “sheepherders monument.” You could see it for miles around.

Post Office Creek, which runs into the Lochsa, got its name from a misunderstanding about Nez Perce cairns in the area. Meriwether Lewis wrote about them in his June 27, 1806 journal entry: “…on this eminence the nativs have raised a conic mound of Stons of 6 or 8 feet high and erected a pine pole of 15 feet long.” According to Borg Hendrickson and Linwood Laughy’s 1989 book, Clearwater Country!, two such mounds were at the head of the creek. They became known as Indian Post Office because people believed the Nez Perce left messages for one another on or in the cairns. Lewis had been told they were markers for trails and fishing sites, which seems more likely. Here a hiker is resting on a stone chair built into the base of a large rock cairn on the top of Granite Peak in the Coeur d’Alene River Ranger District. Nearby were additional rock chairs constructed Adirondack-style, with views of a mountain lake at the base of the peak. Photo Courtesy of the US Forest Service.

Here a hiker is resting on a stone chair built into the base of a large rock cairn on the top of Granite Peak in the Coeur d’Alene River Ranger District. Nearby were additional rock chairs constructed Adirondack-style, with views of a mountain lake at the base of the peak. Photo Courtesy of the US Forest Service.  Indian Post Office, courtesy of Dr. Ed Brenegar.

Indian Post Office, courtesy of Dr. Ed Brenegar.

Just don’t. Artistic as your stones may be, they are a distraction from the natural beauty people have come to see. Moving rocks around disturbs micro-ecosystems, often killing creepy crawly critters that might not be on anyone’s list of favorite animals, but are an important part of nature. If you must stack, do it in your yard. End of editorial.

Stone cairns are common on all continents. Stacking rocks is an ancient way to mark things. They may be memorial markers, markers to locate caches, and in later years, property markers on the corner of lots.

In Idaho, Basque sheepherders made stone cairns to mark trails or just to pass the time. They are called “harrimutilak’ or stone boys. They could be over six feet tall. I remember one at the top of Garden Creek Peak in Bingham County when I was a kid. It may not have been a Basque cairn, since it was on the Fort Hall Reservation, but I remember my dad calling it a “sheepherders monument.” You could see it for miles around.

Post Office Creek, which runs into the Lochsa, got its name from a misunderstanding about Nez Perce cairns in the area. Meriwether Lewis wrote about them in his June 27, 1806 journal entry: “…on this eminence the nativs have raised a conic mound of Stons of 6 or 8 feet high and erected a pine pole of 15 feet long.” According to Borg Hendrickson and Linwood Laughy’s 1989 book, Clearwater Country!, two such mounds were at the head of the creek. They became known as Indian Post Office because people believed the Nez Perce left messages for one another on or in the cairns. Lewis had been told they were markers for trails and fishing sites, which seems more likely.

Here a hiker is resting on a stone chair built into the base of a large rock cairn on the top of Granite Peak in the Coeur d’Alene River Ranger District. Nearby were additional rock chairs constructed Adirondack-style, with views of a mountain lake at the base of the peak. Photo Courtesy of the US Forest Service.

Here a hiker is resting on a stone chair built into the base of a large rock cairn on the top of Granite Peak in the Coeur d’Alene River Ranger District. Nearby were additional rock chairs constructed Adirondack-style, with views of a mountain lake at the base of the peak. Photo Courtesy of the US Forest Service.  Indian Post Office, courtesy of Dr. Ed Brenegar.

Indian Post Office, courtesy of Dr. Ed Brenegar.

Published on September 08, 2023 04:00

September 7, 2023

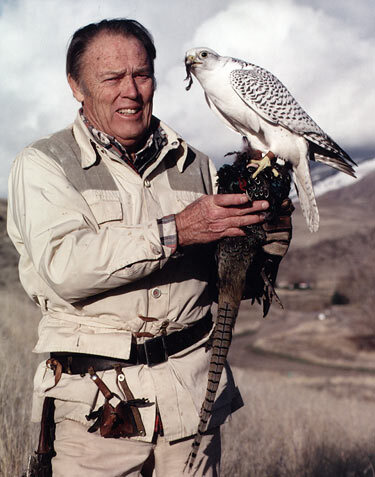

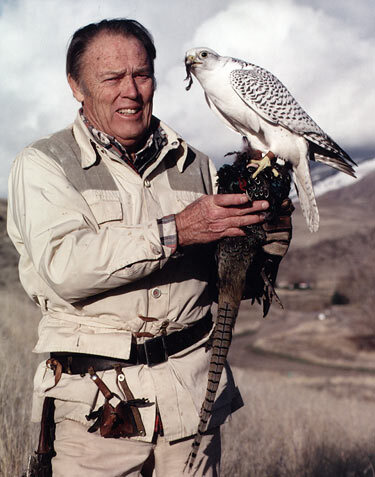

Idaho's Raptor Man

Idaho is a mecca for raptor lovers from all over the world. That’s because it is a magnet for birds of prey. The World Center for Birds of Prey is in Boise, Boise State University is home to the Raptor Research Center and offers the only Masters of Science in Raptor Research, and The Morley Nelson Snake River Birds of Prey National Conservation Area (NCA)is south of Kuna.

The birds congregate in the NCA not because it is a protected area, but because it is an ideal place for raptors to live. The uplift of air from the Snake River Canyon makes flying and gliding (sorry) a breeze for the birds, and the uplands above the canyon rim provide habitat for ground squirrels and other critters the birds consider lunch.

Morley Nelson figured that out when he first saw the canyon in the late 1940s. He had developed a love for raptors—especially peregrine falcons—growing up on a farm in North Dakota. When he moved to Idaho, following a WWII stint with the famous Tenth Mountain Division, he went out to the Snake River Canyon to see if he could find some raptors. He found a few. There are typically about 800 pairs of hawks, eagles, owls, and falcons that nest there each spring. It’s the greatest concentration of nesting raptors in North America, and probably the world.

Nelson became evangelical about the birds and their Snake River Canyon habitat. He worked on films about the birds with Walt Disney, Paramount Pictures, the Public Broadcasting System, and others. His passion for the birds was contagious, and through his efforts public understanding of their role in the natural world was greatly enhanced.

Morley Nelson convinced Secretary of the Interior Rogers Morton to establish the Snake River Birds of Prey Natural area in 1971, and an expansion of the area by Interior Secretary Cecil Andrus in 1980. Then in 1993, US Representative Larry LaRocco led an effort in Congress to designate some 485,000 acres as a National Conservation Area.

It was also Nelson who led the effort to convince the Peregrine Fund to relocate to Boise and build the World Center for Birds of Prey south of town.

While those efforts were going on, Nelson was also doing pioneer work on an effort to save raptors from power line electrocution. He worked with the Edison Electric Institute and Idaho Power to study how raptors used those manmade perches known as power poles. Through those efforts poles are now designed to minimize electrocution and even provide safe nesting areas for the birds.

When Morley Nelson passed away in 2005 he had unquestionably done more to save and protect raptors than any other single person.

For more on Morley Nelson, see his biography, Cool North Wind , written by Steve Steubner.

The birds congregate in the NCA not because it is a protected area, but because it is an ideal place for raptors to live. The uplift of air from the Snake River Canyon makes flying and gliding (sorry) a breeze for the birds, and the uplands above the canyon rim provide habitat for ground squirrels and other critters the birds consider lunch.

Morley Nelson figured that out when he first saw the canyon in the late 1940s. He had developed a love for raptors—especially peregrine falcons—growing up on a farm in North Dakota. When he moved to Idaho, following a WWII stint with the famous Tenth Mountain Division, he went out to the Snake River Canyon to see if he could find some raptors. He found a few. There are typically about 800 pairs of hawks, eagles, owls, and falcons that nest there each spring. It’s the greatest concentration of nesting raptors in North America, and probably the world.

Nelson became evangelical about the birds and their Snake River Canyon habitat. He worked on films about the birds with Walt Disney, Paramount Pictures, the Public Broadcasting System, and others. His passion for the birds was contagious, and through his efforts public understanding of their role in the natural world was greatly enhanced.

Morley Nelson convinced Secretary of the Interior Rogers Morton to establish the Snake River Birds of Prey Natural area in 1971, and an expansion of the area by Interior Secretary Cecil Andrus in 1980. Then in 1993, US Representative Larry LaRocco led an effort in Congress to designate some 485,000 acres as a National Conservation Area.

It was also Nelson who led the effort to convince the Peregrine Fund to relocate to Boise and build the World Center for Birds of Prey south of town.

While those efforts were going on, Nelson was also doing pioneer work on an effort to save raptors from power line electrocution. He worked with the Edison Electric Institute and Idaho Power to study how raptors used those manmade perches known as power poles. Through those efforts poles are now designed to minimize electrocution and even provide safe nesting areas for the birds.

When Morley Nelson passed away in 2005 he had unquestionably done more to save and protect raptors than any other single person.

For more on Morley Nelson, see his biography, Cool North Wind , written by Steve Steubner.

Published on September 07, 2023 04:00

September 6, 2023

Dempsey Idaho Was a Hot Spot

So, you haven’t heard of Dempsey, largely because it wasn’t called that for long. Dempsey was in southeastern Idaho, where Bob Dempsey, a trapper, had his camp for about 10 years from 1851 to 1861. He moved to the Montana gold fields after that and dropped off the map. The town named after him got a post office in 1895, but the name Dempsey disappeared in 1915, when they started calling the place Lava Hot Springs, which is more reflective of the major draw to the town.

The hot springs were deeded to the State of Idaho in 1902. In 1913, the hot springs site became a state park, and the state built a natatorium there in 1918. In 1967 management of the site was taken over by the newly formed Lava Hot Springs Foundation, a group appointed by the governor to run the place. That foundation is still in existence today, running a large complex of water features.

The pools at Lava Hot Springs are from 102 to 112 degrees. Their Olympic-sized outdoor pool has diving boards, high and low diving platforms, and corkscrew waterslides. Next to the pool is the big waterslide that comes swooping in right across the main road into town.

Located about 45 minutes south of Pocatello not far off I-15, Lava Hot Springs is a major draw for Utah recreationists.

Early photo of the baths at Lava Hot Springs.

Early photo of the baths at Lava Hot Springs.

The hot springs were deeded to the State of Idaho in 1902. In 1913, the hot springs site became a state park, and the state built a natatorium there in 1918. In 1967 management of the site was taken over by the newly formed Lava Hot Springs Foundation, a group appointed by the governor to run the place. That foundation is still in existence today, running a large complex of water features.

The pools at Lava Hot Springs are from 102 to 112 degrees. Their Olympic-sized outdoor pool has diving boards, high and low diving platforms, and corkscrew waterslides. Next to the pool is the big waterslide that comes swooping in right across the main road into town.

Located about 45 minutes south of Pocatello not far off I-15, Lava Hot Springs is a major draw for Utah recreationists.

Early photo of the baths at Lava Hot Springs.

Early photo of the baths at Lava Hot Springs.

Published on September 06, 2023 04:00

September 5, 2023

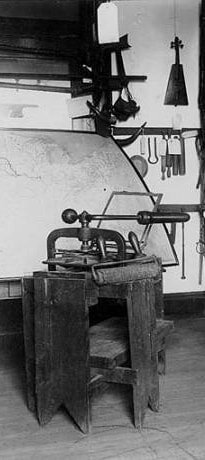

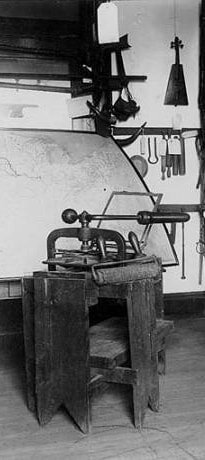

Idaho's First Press Came from Hawaii

Idaho became a state in 1890, as probably everyone reading this knows. It was 1959 before Hawaii became a state, yet it was to Hawaii that Reverend Henry Harmon Spalding turned to obtain a major machine of civilization. In 1838 Spalding wrote to the Congregational mission in Honolulu, “requesting the donation of a second-hand press and that the Sandwich Islands Mission should instruct someone, to be sent there from Oregon, in the art of printing, and in the meantime print a few small books in Nez Perces.”

The Sandwich Islands would later become the Hawaiian Islands, and the Oregon Spalding referred to what was then Oregon Territory, where his own Lapwai Mission stood. It would not become Idaho Territory until 1863, long after the Spaldings had fled the territory.

According to the book, The Lapwai Mission Press, by Wilfred P. Schoenberg, S.J., from which the quotes in this post are also taken, no book of Nez Perce was printed in Hawaii, though a proof consisting of a couple of pages of set type for a Nez Perce spelling book created by Spalding and his wife Eliza was printed. Instead, the Sandwich Island Mission prepared to fulfill Spalding’s main request, which was for a printing press to be sent to Lapwai.

The press they would send, was the fifth press in Hawaii. It would be the first in the Pacific Northwest, the eighth in what would become the West of the United States. Importantly, it is the only one of those first eight still in existence.

The Sandwich Island Mission sent not just the press, but the pressman. Edwin Oscar Hall, a lay minister in the congregation, would accompany the press to Lapwai. He agreed to do so partly because his wife’s health would benefit from a cooler climate.

Hall set up the press and began working it on May 16, 1839, three days after they arrived at Lapwai. He set about running proof sheets, and by May 24 he had printed four hundred copies of an 8-page book using an artificial alphabet of the Nez Perce Spalding had devised. This “reader for beginners and children” was the first book printed in Oregon Territory. If you had a copy of that thin tome it would be worth quite a lot today. But you don’t, because shortly after the little books were printed they were destroyed.

In July, 1839, all the missionaries of Oregon Territory got together to discuss the book. They found Spalding’s attempt to create a Nez Perce alphabet and provide a means for translating the language could not “be relied on for books, or as a standard in any sense.”

The Reverend Asa Bowen Smith edited a new version of Spalding’s book, which would be called First Book: Designed For Children And New Beginners.” It was published in August, 1839.

The book the missionaries rejected and ordered destroyed, lived on in a way. In later years it was discovered that some pages of that earliest printing were used in the cover and binding of the new “first book.”

The printer Hall and his wife returned to the Sandwich Islands in May of 1840, leaving the press behind.

In 1842 or 43 the press was used to print a book for young readers in the Spokane language, a book of The Laws and Statutes, and a hymn book. Spalding labored for two years on a Nez Perce translation of the gospel of St. Matthew. It was printed in 1845. That year the last of the imprints from the Lapwai press appeared, a “vocabulary” of Nez Perce and English words. In 1846 the press was moved to The Dalles. It had a short history printing The Oregon and American Evangelical Unionist, and, years later, in 1875, was donated to the Oregon State Historical Society in Salem, where it resides today.

The Lapwai press at the Oregon State Historical Society. University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, IND0323

The Lapwai press at the Oregon State Historical Society. University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, IND0323

The Sandwich Islands would later become the Hawaiian Islands, and the Oregon Spalding referred to what was then Oregon Territory, where his own Lapwai Mission stood. It would not become Idaho Territory until 1863, long after the Spaldings had fled the territory.

According to the book, The Lapwai Mission Press, by Wilfred P. Schoenberg, S.J., from which the quotes in this post are also taken, no book of Nez Perce was printed in Hawaii, though a proof consisting of a couple of pages of set type for a Nez Perce spelling book created by Spalding and his wife Eliza was printed. Instead, the Sandwich Island Mission prepared to fulfill Spalding’s main request, which was for a printing press to be sent to Lapwai.

The press they would send, was the fifth press in Hawaii. It would be the first in the Pacific Northwest, the eighth in what would become the West of the United States. Importantly, it is the only one of those first eight still in existence.

The Sandwich Island Mission sent not just the press, but the pressman. Edwin Oscar Hall, a lay minister in the congregation, would accompany the press to Lapwai. He agreed to do so partly because his wife’s health would benefit from a cooler climate.

Hall set up the press and began working it on May 16, 1839, three days after they arrived at Lapwai. He set about running proof sheets, and by May 24 he had printed four hundred copies of an 8-page book using an artificial alphabet of the Nez Perce Spalding had devised. This “reader for beginners and children” was the first book printed in Oregon Territory. If you had a copy of that thin tome it would be worth quite a lot today. But you don’t, because shortly after the little books were printed they were destroyed.

In July, 1839, all the missionaries of Oregon Territory got together to discuss the book. They found Spalding’s attempt to create a Nez Perce alphabet and provide a means for translating the language could not “be relied on for books, or as a standard in any sense.”

The Reverend Asa Bowen Smith edited a new version of Spalding’s book, which would be called First Book: Designed For Children And New Beginners.” It was published in August, 1839.

The book the missionaries rejected and ordered destroyed, lived on in a way. In later years it was discovered that some pages of that earliest printing were used in the cover and binding of the new “first book.”

The printer Hall and his wife returned to the Sandwich Islands in May of 1840, leaving the press behind.

In 1842 or 43 the press was used to print a book for young readers in the Spokane language, a book of The Laws and Statutes, and a hymn book. Spalding labored for two years on a Nez Perce translation of the gospel of St. Matthew. It was printed in 1845. That year the last of the imprints from the Lapwai press appeared, a “vocabulary” of Nez Perce and English words. In 1846 the press was moved to The Dalles. It had a short history printing The Oregon and American Evangelical Unionist, and, years later, in 1875, was donated to the Oregon State Historical Society in Salem, where it resides today.

The Lapwai press at the Oregon State Historical Society. University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, IND0323

The Lapwai press at the Oregon State Historical Society. University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, IND0323

Published on September 05, 2023 04:00

September 4, 2023

How to be a Billionaire

J.R. Simplots origin story, as it were, is well known because he loved telling it. It’s a great story, so I’ll tell it again. By origin, I mean how he got to be wealthy.

John Richard Simplot understood how to make a dollar. He struck out on his own at age 14, leaving family and school behind. Not far behind, though. Simplot moved into a boarding house in his hometown of Declo to avoid arguments with his father. Leaving school at that age was quite common at the time. Young men had to get on with their working lives.

Simplot learned the basics of being a billionaire in that boarding house because of the eight school teachers who also boarded there for a dollar a day. Those teachers may have made some effort to pass on some knowledge to Simplot, but what he really learned was that they were willing to pass on half their salaries to him.

It was the middle of the Great Depression and money was tight. Teachers were paid not in dollars, but in scrip. Scrip was essentially an IOU, promising to pay the teachers at a later date, with a little interest. The teachers couldn’t wait until a later date, because they had bills to pay right then, such as what it cost to stay at the boarding house.

J.R. had left his home with $80 in gold certificates, money he had made from the sale of fat lambs. Carrying around that much money during hard times wasn’t wise, so he started a bank account. When he found out the boarding house residents were willing to sell their scrip to him for half its face value, he put that account to good use. He could afford to wait until the scrip matured.

In his biography, A billion the hard way , by Louie Attebery, Simplot is quoted as saying, “It wasn’t a lotta money, but it was enough to make some money. I’d buy that scrip every month when [they got paid]. They had to pay their board bill…Damn board bill was about half their [salary]. Tough. You talk about tough times; they were tough! Tough, boy! But I accumulated a few hundred dollars, and I made some money.”

He had a lot of stories like that, because spotting a bargain or a deal was his life. Simplot was known as the potato king because his company invented a way to process French fries that caught on just a little bit with companies such as McDonalds. He was big in fertilizer, raising cattle, and funding the development of microchips. The latter proving that he never lost the business acumen that he gained back at that boarding house in Declo.

J.R. Simplot was Idaho’s first billionaire. In 2007 he was the 89th richest person in the United States, with a personal fortune estimated to be about $3.6 billion dollars. When he passed away in 2008 at age 99, Jack Simplot was the oldest billionaire on the Forbes 400 list.

John Richard Simplot understood how to make a dollar. He struck out on his own at age 14, leaving family and school behind. Not far behind, though. Simplot moved into a boarding house in his hometown of Declo to avoid arguments with his father. Leaving school at that age was quite common at the time. Young men had to get on with their working lives.

Simplot learned the basics of being a billionaire in that boarding house because of the eight school teachers who also boarded there for a dollar a day. Those teachers may have made some effort to pass on some knowledge to Simplot, but what he really learned was that they were willing to pass on half their salaries to him.

It was the middle of the Great Depression and money was tight. Teachers were paid not in dollars, but in scrip. Scrip was essentially an IOU, promising to pay the teachers at a later date, with a little interest. The teachers couldn’t wait until a later date, because they had bills to pay right then, such as what it cost to stay at the boarding house.

J.R. had left his home with $80 in gold certificates, money he had made from the sale of fat lambs. Carrying around that much money during hard times wasn’t wise, so he started a bank account. When he found out the boarding house residents were willing to sell their scrip to him for half its face value, he put that account to good use. He could afford to wait until the scrip matured.

In his biography, A billion the hard way , by Louie Attebery, Simplot is quoted as saying, “It wasn’t a lotta money, but it was enough to make some money. I’d buy that scrip every month when [they got paid]. They had to pay their board bill…Damn board bill was about half their [salary]. Tough. You talk about tough times; they were tough! Tough, boy! But I accumulated a few hundred dollars, and I made some money.”

He had a lot of stories like that, because spotting a bargain or a deal was his life. Simplot was known as the potato king because his company invented a way to process French fries that caught on just a little bit with companies such as McDonalds. He was big in fertilizer, raising cattle, and funding the development of microchips. The latter proving that he never lost the business acumen that he gained back at that boarding house in Declo.

J.R. Simplot was Idaho’s first billionaire. In 2007 he was the 89th richest person in the United States, with a personal fortune estimated to be about $3.6 billion dollars. When he passed away in 2008 at age 99, Jack Simplot was the oldest billionaire on the Forbes 400 list.

Published on September 04, 2023 04:00

September 3, 2023

The Good Ol' Hornikabrinka

Ah, what can one say about Hornikabrinka? Apparently, almost nothing. If you search for the word in The Idaho Statesman digital archives, you get several hits that talk about the 1913 revival of Hornikabrinka, which was to be held in conjunction with the semicentennial of the State of Idaho and the creation of Fort Boise that September. They were looking for “old-timers” who might be convinced to “reenact the stunts they used to do during the old time affairs.” What those stunts were is anyone’s guess.

There was little spate of interest in Hornikabrinka in 1968 when a reader asked the Action Post columnist at the Statesman about it. They provided an answer that, though sketchy, set me on the right track. The columnist spelled it Hornikibrinki. The spelling of the event also included Horniki Brinki and Hornika Brinka in some references.

Speculation about exactly what it was, what it meant, and how it started seemed to be part of the fun. A headline from the August 1913 Idaho Statesman read “Hornika Brinika—What’s His Batting Average?” The reporter had walked around town asking people what the word or words meant to them. “Is it a drink, a germ, or a disease?”

During the 1913 celebration, it was billed as a revival of the tradition from around the founding of Boise. George Washington Stilts, a well-known practical joker in town during those earliest days, seemed to be one of the ringleaders of those celebrations. Which were exactly what?

Think Mardis Gras.

The September 27 Idaho Statesman had a full page about the festivities, headlined, “FROLIC OF THE FUNMAKERS—Mask Parade and Street Dance a Wild Revel of Pleasure.” The article began, “Herniki Briniki—symbol for expression of a wild, care free, abandoned, and yet not unduly boisterous variety of mirth that only that phrase will describe…” It continued “Fully 500 maskers took part in the parade, and such costumes! From the beautiful to the ridiculous, with the emphasis on the latter, they ranged, in a kaleidoscopic and seemingly endless variety.”

Then, showing the cultural sensitivity of the times it went on, “Every character commonly portrayed on the stage, from the pawnshop Jew and the plantation darkey, the heathen Chinee (sic) was there in half a dozen places.”

Moving on.

“At Sixth and Main streets a stop was made, and with the devil’s blacksmith shop as a backdrop and the red lights from The Statesman office lighting up the scene, the maskers staged the devil’s ball to the tune of that popular rag in a manner that would have set a grove of weeping willows to laughter.”

Now, there’s a metaphor you don’t often see.

When the parade was done, a dance commenced in front of the statehouse. “The capitol steps were black with humanity, and no space from which one could obtain a view of the dance space was vacant.”

All in all, good, clean fun. So, Boise kind of owns the name, however you spell it. It sounds way more entertaining than any parade I’ve ever seen in town. Someone should claim the name—however you want to spell it—and fest away.

There was little spate of interest in Hornikabrinka in 1968 when a reader asked the Action Post columnist at the Statesman about it. They provided an answer that, though sketchy, set me on the right track. The columnist spelled it Hornikibrinki. The spelling of the event also included Horniki Brinki and Hornika Brinka in some references.

Speculation about exactly what it was, what it meant, and how it started seemed to be part of the fun. A headline from the August 1913 Idaho Statesman read “Hornika Brinika—What’s His Batting Average?” The reporter had walked around town asking people what the word or words meant to them. “Is it a drink, a germ, or a disease?”

During the 1913 celebration, it was billed as a revival of the tradition from around the founding of Boise. George Washington Stilts, a well-known practical joker in town during those earliest days, seemed to be one of the ringleaders of those celebrations. Which were exactly what?

Think Mardis Gras.

The September 27 Idaho Statesman had a full page about the festivities, headlined, “FROLIC OF THE FUNMAKERS—Mask Parade and Street Dance a Wild Revel of Pleasure.” The article began, “Herniki Briniki—symbol for expression of a wild, care free, abandoned, and yet not unduly boisterous variety of mirth that only that phrase will describe…” It continued “Fully 500 maskers took part in the parade, and such costumes! From the beautiful to the ridiculous, with the emphasis on the latter, they ranged, in a kaleidoscopic and seemingly endless variety.”

Then, showing the cultural sensitivity of the times it went on, “Every character commonly portrayed on the stage, from the pawnshop Jew and the plantation darkey, the heathen Chinee (sic) was there in half a dozen places.”

Moving on.

“At Sixth and Main streets a stop was made, and with the devil’s blacksmith shop as a backdrop and the red lights from The Statesman office lighting up the scene, the maskers staged the devil’s ball to the tune of that popular rag in a manner that would have set a grove of weeping willows to laughter.”

Now, there’s a metaphor you don’t often see.

When the parade was done, a dance commenced in front of the statehouse. “The capitol steps were black with humanity, and no space from which one could obtain a view of the dance space was vacant.”

All in all, good, clean fun. So, Boise kind of owns the name, however you spell it. It sounds way more entertaining than any parade I’ve ever seen in town. Someone should claim the name—however you want to spell it—and fest away.

Published on September 03, 2023 04:00

September 2, 2023

Idaho's Traveling Forts

One of the more confusing things about Idaho history is keeping track of which fort someone is talking about. Two were built in 1834 to begin the confusion. First, Fort Hall, on the south bank of the Snake River near present-day Pocatello, was established by Nathaniel Jarvis Wyeth, who needed a site from which to sell trade goods. The Hudson’s Bay Company, at least partly to provide competition for Fort Hall, built a trading post at the mouth of the Boise River where it flows into the Snake that same year. Two years later, the Hudson’s Bay Company purchased Ft. Hall.

Fort Boise, the trading post, operated until about 1855. The military Fort Boise was established in 1863, about 40 miles upriver from where the Hudson’s Bay trading post had been. The town of Boise was established next to the fort the same year.

Fort Hall moved around a little more. It stayed in its original location until 1855, serving first as a fur trading post, then, as the pioneers started streaming through as an important supply stop on the Oregon and California trails. In 1869 and 1870, the first military Fort Hall was built on Lincoln Creek, where it streams into the Blackfoot River. It remained there until 1883 when the barracks moved to Ross Fork Creek, about 25 miles to the west.

To confuse things a bit further, you can now visit the full-scale Fort Hall Replica in Pocatello. It’s not at the original site, but it is worth a visit. And, finally, to muddy the historical waters, there is the town of Fort Hall, which is close to the site of the original trading post.

Idaho's military Fort Hall in 1872. The Hayden Expedition is camped in the foreground. Photo by William Henry Jackson.

Idaho's military Fort Hall in 1872. The Hayden Expedition is camped in the foreground. Photo by William Henry Jackson.

Fort Boise, the trading post, operated until about 1855. The military Fort Boise was established in 1863, about 40 miles upriver from where the Hudson’s Bay trading post had been. The town of Boise was established next to the fort the same year.

Fort Hall moved around a little more. It stayed in its original location until 1855, serving first as a fur trading post, then, as the pioneers started streaming through as an important supply stop on the Oregon and California trails. In 1869 and 1870, the first military Fort Hall was built on Lincoln Creek, where it streams into the Blackfoot River. It remained there until 1883 when the barracks moved to Ross Fork Creek, about 25 miles to the west.

To confuse things a bit further, you can now visit the full-scale Fort Hall Replica in Pocatello. It’s not at the original site, but it is worth a visit. And, finally, to muddy the historical waters, there is the town of Fort Hall, which is close to the site of the original trading post.

Idaho's military Fort Hall in 1872. The Hayden Expedition is camped in the foreground. Photo by William Henry Jackson.

Idaho's military Fort Hall in 1872. The Hayden Expedition is camped in the foreground. Photo by William Henry Jackson.

Published on September 02, 2023 04:00

September 1, 2023

The First Settlers Married in Idaho

Do you know who the first non-native couple married in Idaho was? It could be difficult to track down. Still, I have a nomination. Let’s see if you know of a couple who were married in Idaho earlier.

I’m talking about a place officially named Idaho, so the first candidates would have to have been married on or after March 3, 1863, when Idaho became a territory.

My candidates are Niels and Mary Christofferson Anderson, who were married in Morristown on July 30, 1863. Morristown lasted only a few years and later became a part of Soda Springs.

The year before, 15-year-old Mary Christofferson had been struck in the face by a cannonball, the beginning shot fired in what would be known as the Morrisite War, which took place at Kington Fort, Utah. Joseph Morris and his followers were holed up there waiting for the Second Coming when a group called the Mormon Militia came to demand the release of a prisoner they were holding. Morris had formed the breakaway Church of the Newborn when Brigham Young refused to acknowledge the prophecies of Morris.

In the siege that followed, several Morrisites were killed, including their leader. About half of the followers of Morris were escorted into the newly formed Idaho Territory in May 1863, where they founded Morristown.

Mary Anderson did not let her disfigurement—her jaw was shot off—ruin her life. She and Niels raised a thriving family. Many of their descendants live in Idaho today.

This was the shortest possible telling of the story of the Morrisite War. I give a one-hour presentation about the war to interested groups. You can also watch my YouTube video about it. The best book available on the subject is Joseph Morris: and the Saga of the Morrisites Revisited , by C. Leroy Anderson.

So, do you know of another non-native couple who were married in Idaho earlier?

Mary Christofferson Anderson

Mary Christofferson Anderson

I’m talking about a place officially named Idaho, so the first candidates would have to have been married on or after March 3, 1863, when Idaho became a territory.

My candidates are Niels and Mary Christofferson Anderson, who were married in Morristown on July 30, 1863. Morristown lasted only a few years and later became a part of Soda Springs.

The year before, 15-year-old Mary Christofferson had been struck in the face by a cannonball, the beginning shot fired in what would be known as the Morrisite War, which took place at Kington Fort, Utah. Joseph Morris and his followers were holed up there waiting for the Second Coming when a group called the Mormon Militia came to demand the release of a prisoner they were holding. Morris had formed the breakaway Church of the Newborn when Brigham Young refused to acknowledge the prophecies of Morris.

In the siege that followed, several Morrisites were killed, including their leader. About half of the followers of Morris were escorted into the newly formed Idaho Territory in May 1863, where they founded Morristown.

Mary Anderson did not let her disfigurement—her jaw was shot off—ruin her life. She and Niels raised a thriving family. Many of their descendants live in Idaho today.

This was the shortest possible telling of the story of the Morrisite War. I give a one-hour presentation about the war to interested groups. You can also watch my YouTube video about it. The best book available on the subject is Joseph Morris: and the Saga of the Morrisites Revisited , by C. Leroy Anderson.

So, do you know of another non-native couple who were married in Idaho earlier?

Mary Christofferson Anderson

Mary Christofferson Anderson

Published on September 01, 2023 04:00

August 31, 2023

A Major Force in Art and Design

Edgar Miller was born in or near Idaho Falls a few weeks before the turn to the Twentieth Century. He was destined to become a major force in the art and design worlds in that century.

Miller knocked around with his brother exploring what there was to explore near his home growing up. They would go camping for days in the nearby hills, where Edgar drew. And drew. Creating pictures of wildflowers was a passion. One of his high school teachers saw his talent and got him accepted at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1917.

He took to the city the way he took to his art, eventually creating a live-work art community much of which exists still today. Most famous for his stained glass, he was a pioneer in graphic art advertising, and influential in architecture.

Miller loved growing up in Idaho. He saw a painting of Custer’s Last Stand when he was four and from that moment wanted nothing more than to be an artist. He began sketching everything he saw. Much of his work was inspired by his childhood in and around the frontier town.

For more on Edgar Miller, see this Time Magazine slideshow of his work. A comprehensive article about Miller is available from on the CITYLAB website. The Edgar Miller Legacy is a nonprofit dedicated to preserving the art and "handmade homes" he created. Finally, there is quite a lavish book called Edgar Miller and the Hand-Made Home: Chicago's Forgotten Renaissance Man.

Thanks to architectural historian Julie Williams of Idaho Falls for telling me about Edgar Miller.

Miller knocked around with his brother exploring what there was to explore near his home growing up. They would go camping for days in the nearby hills, where Edgar drew. And drew. Creating pictures of wildflowers was a passion. One of his high school teachers saw his talent and got him accepted at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1917.

He took to the city the way he took to his art, eventually creating a live-work art community much of which exists still today. Most famous for his stained glass, he was a pioneer in graphic art advertising, and influential in architecture.

Miller loved growing up in Idaho. He saw a painting of Custer’s Last Stand when he was four and from that moment wanted nothing more than to be an artist. He began sketching everything he saw. Much of his work was inspired by his childhood in and around the frontier town.

For more on Edgar Miller, see this Time Magazine slideshow of his work. A comprehensive article about Miller is available from on the CITYLAB website. The Edgar Miller Legacy is a nonprofit dedicated to preserving the art and "handmade homes" he created. Finally, there is quite a lavish book called Edgar Miller and the Hand-Made Home: Chicago's Forgotten Renaissance Man.

Thanks to architectural historian Julie Williams of Idaho Falls for telling me about Edgar Miller.

Published on August 31, 2023 04:00

August 30, 2023

Bridges Gone Bad

The Idaho Transportation Department has released thousands of digitized photos from their files for the public’s enjoyment. In looking at the database recently, I decided to pull together a little series of bridges gone bad.

This is an old bridge at Cataldo, circa 1910. It shows the distorted trusses and the temporary braces put in place to stave off a complete collapse. It’s doubtful there is any remnant of this old bridge today.

This is an old bridge at Cataldo, circa 1910. It shows the distorted trusses and the temporary braces put in place to stave off a complete collapse. It’s doubtful there is any remnant of this old bridge today.

This is the collapse of the Parma Bridge. It looks to me like it was probably 1950s, by the way the men are dressed.

This is the collapse of the Parma Bridge. It looks to me like it was probably 1950s, by the way the men are dressed.

Perhaps the most dramatic bridge collapse in the ITD files is this one, which caught a Union Pacific Bus as it tried to cross. This may have been a bridge across the Bear River. Does anyone have any information about this incident?

Perhaps the most dramatic bridge collapse in the ITD files is this one, which caught a Union Pacific Bus as it tried to cross. This may have been a bridge across the Bear River. Does anyone have any information about this incident?  Some of the photos are more recent. This is an overpass across I-84 near Burley after a truck crashed into a support in 1988.

Some of the photos are more recent. This is an overpass across I-84 near Burley after a truck crashed into a support in 1988.

This is an old bridge at Cataldo, circa 1910. It shows the distorted trusses and the temporary braces put in place to stave off a complete collapse. It’s doubtful there is any remnant of this old bridge today.

This is an old bridge at Cataldo, circa 1910. It shows the distorted trusses and the temporary braces put in place to stave off a complete collapse. It’s doubtful there is any remnant of this old bridge today. This is the collapse of the Parma Bridge. It looks to me like it was probably 1950s, by the way the men are dressed.

This is the collapse of the Parma Bridge. It looks to me like it was probably 1950s, by the way the men are dressed. Perhaps the most dramatic bridge collapse in the ITD files is this one, which caught a Union Pacific Bus as it tried to cross. This may have been a bridge across the Bear River. Does anyone have any information about this incident?

Perhaps the most dramatic bridge collapse in the ITD files is this one, which caught a Union Pacific Bus as it tried to cross. This may have been a bridge across the Bear River. Does anyone have any information about this incident?  Some of the photos are more recent. This is an overpass across I-84 near Burley after a truck crashed into a support in 1988.

Some of the photos are more recent. This is an overpass across I-84 near Burley after a truck crashed into a support in 1988.

Published on August 30, 2023 04:00