Rick Just's Blog, page 51

August 9, 2023

A Deadly Explorer that came West Before Lewis and Clark

The Corps of Discovery, also known as the Lewis and Clark Expedition, travelled through a wilderness making new discoveries, naming plants and animals and mountains and rivers for the first time, and inspiring awe in the primitive people who barely subsisted there. Right?

Well, it was all new to them, but people had operated successful societies in that “unexplored” country for thousands of years. Those plants and animals and mountains and rivers already had names. The people who lived there were interested in the innovations the Corps of Discovery brought with them from pants with pockets to pistols and ammunition. But they probably thought the white men (and one black man) were woefully ignorant when they went hungry with food so easily attainable nearby.

Wilderness? The natives had no such concept. This was no unoccupied frontier. The Mandan villages in what is now North Dakota where the Corps spent the winter of 1804-1805 were more densely populated than St. Louis, according to an essay by Roberta Conner in the 2006 anthology Lewis and Clark Through Indian Eyes *. The Expedition itself estimated there were 114 tribes living along or near their route.

What they did not report, because they did not know it, was that one newcomer from the Old World had preceded them, devastating the Indian population. According to Charles C. Mann in his book 1491, New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus *, smallpox took out as much as 90 percent of the native population in the Americas. Mark Trahant, a writer with Indian ancestry from Blackfoot, noted in the above-mentioned anthology that a smallpox epidemic swept through Shoshone country around 1780.

Lewis and Clark encountered a considerable civilization on their journey, though one much reduced from what it had been a few generations before.

If you would like to learn more about how the indigenous people of the Americas lived and the impact epidemic had on them, I recommend the books previously mentioned and Guns, Germs, and Steel * by Jared Diamond.

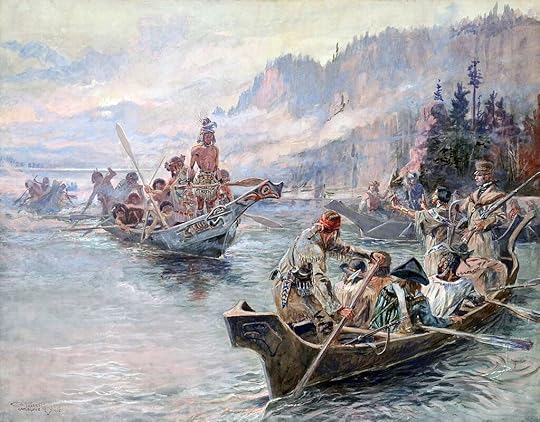

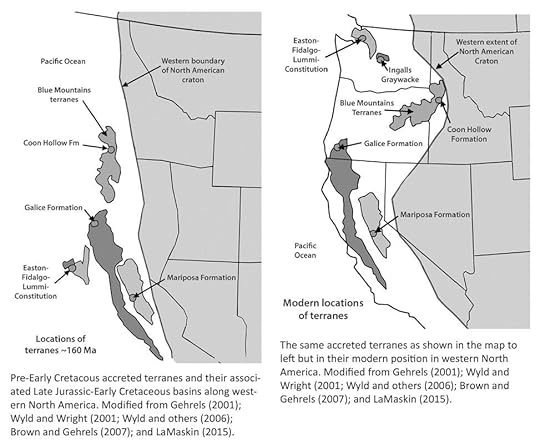

Lewis and Clark on the Lower Columbia, by Charles M. Russell.

Lewis and Clark on the Lower Columbia, by Charles M. Russell.

Well, it was all new to them, but people had operated successful societies in that “unexplored” country for thousands of years. Those plants and animals and mountains and rivers already had names. The people who lived there were interested in the innovations the Corps of Discovery brought with them from pants with pockets to pistols and ammunition. But they probably thought the white men (and one black man) were woefully ignorant when they went hungry with food so easily attainable nearby.

Wilderness? The natives had no such concept. This was no unoccupied frontier. The Mandan villages in what is now North Dakota where the Corps spent the winter of 1804-1805 were more densely populated than St. Louis, according to an essay by Roberta Conner in the 2006 anthology Lewis and Clark Through Indian Eyes *. The Expedition itself estimated there were 114 tribes living along or near their route.

What they did not report, because they did not know it, was that one newcomer from the Old World had preceded them, devastating the Indian population. According to Charles C. Mann in his book 1491, New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus *, smallpox took out as much as 90 percent of the native population in the Americas. Mark Trahant, a writer with Indian ancestry from Blackfoot, noted in the above-mentioned anthology that a smallpox epidemic swept through Shoshone country around 1780.

Lewis and Clark encountered a considerable civilization on their journey, though one much reduced from what it had been a few generations before.

If you would like to learn more about how the indigenous people of the Americas lived and the impact epidemic had on them, I recommend the books previously mentioned and Guns, Germs, and Steel * by Jared Diamond.

Lewis and Clark on the Lower Columbia, by Charles M. Russell.

Lewis and Clark on the Lower Columbia, by Charles M. Russell.

Published on August 09, 2023 04:00

August 8, 2023

Oceanfront property in Riggins

If you think history doesn’t change, you’re just not paying attention. We learn things all the time that change our interpretation of history. Geology, though, that’s something you can count on.

Well…

Geologists are learning all the time, too. As certifiable human beings, they occasionally make mistakes and frequently disagree with one another.

In my 1990 book, Idaho Snapshots, I joked about oceanfront property in Riggins, because at one time—not exactly last week—the area around Riggins would have overlooked the Pacific Ocean. This was a long time ago, in the Middle Permian to Early Cretaceous periods. I noted that what is now Washington and Oregon would have been an island before tectonic plate movement kissed that prehistorical land into what would become Idaho.

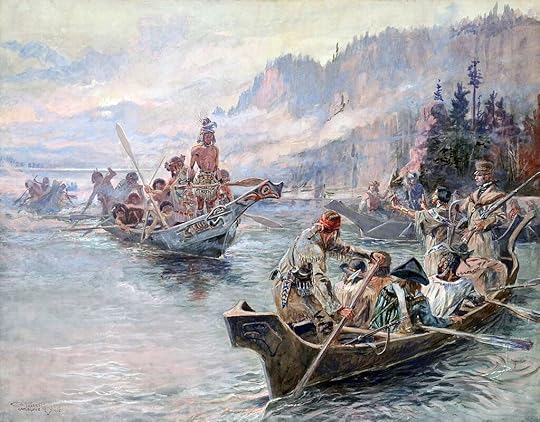

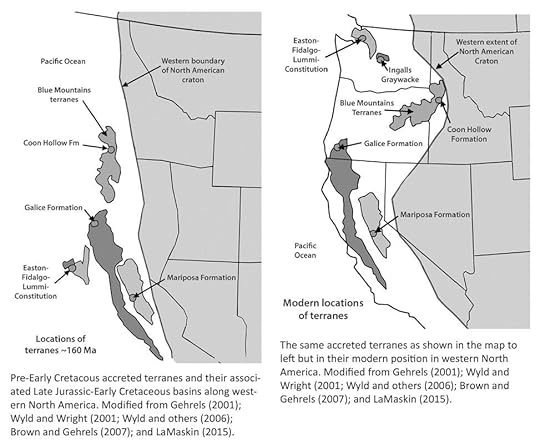

Lands roughly west of Riggins along a north-south squiggly line (not an official term of geology) from Alaska to Mexico did form at different times, play their roles as islands, then snuggle up against the North American continent, adding much beloved land to these United States, including California (see graphic).

Most of these islands were formed by volcanic activity or started as mountain ranges beneath the Pacific. They rode oceanic plates on their journey to their present position. The result is called accreted terrane, meaning that land masses formed somewhere else found a different home. Geologists generally agree that a wide swath of the west coast is accreted terrane. They disagree on exactly when and how it all came together.

Evidence that those islands piled up against the rest of the continent is on display in the Riggins area. The photo below, generously contributed by Terry Maley from his book Idaho Geology, shows where two radically different kinds of rocks are squished side-by-side to form part of what we call Idaho.

Well…

Geologists are learning all the time, too. As certifiable human beings, they occasionally make mistakes and frequently disagree with one another.

In my 1990 book, Idaho Snapshots, I joked about oceanfront property in Riggins, because at one time—not exactly last week—the area around Riggins would have overlooked the Pacific Ocean. This was a long time ago, in the Middle Permian to Early Cretaceous periods. I noted that what is now Washington and Oregon would have been an island before tectonic plate movement kissed that prehistorical land into what would become Idaho.

Lands roughly west of Riggins along a north-south squiggly line (not an official term of geology) from Alaska to Mexico did form at different times, play their roles as islands, then snuggle up against the North American continent, adding much beloved land to these United States, including California (see graphic).

Most of these islands were formed by volcanic activity or started as mountain ranges beneath the Pacific. They rode oceanic plates on their journey to their present position. The result is called accreted terrane, meaning that land masses formed somewhere else found a different home. Geologists generally agree that a wide swath of the west coast is accreted terrane. They disagree on exactly when and how it all came together.

Evidence that those islands piled up against the rest of the continent is on display in the Riggins area. The photo below, generously contributed by Terry Maley from his book Idaho Geology, shows where two radically different kinds of rocks are squished side-by-side to form part of what we call Idaho.

Published on August 08, 2023 04:00

August 7, 2023

Idaho's Camas Prairies

After you’ve topped White Bird Pass, look to your left as you enter the rolling farm country around Grangeville. If you’re there in the early spring you can see patches of blue sometimes so thick they look like rippling ponds. If you’re paying attention you might pull over and read the Idaho Historical Society marker that explains that swatch of color. Camas. The flowering root was a key part of the diet of the Nez Perce.

If you’re a fan of historical markers, you probably already stopped at the one part-way up the steep White Bird grade that marks the beginning of the Nez Perce War. The first shots in that months-long running battle were fired from the top of a low hill as the Indians created a diversion there that allowed Chief Joseph and his people, who were camped on the prairie above, to slip away from soldiers.

When we talk about Camas Prairie, we could be talking about that one. Or we could be talking about the other Camas Prairie near Fairfield. It wasn’t part of the Nez Perce War, but it was the site of a war over the edible bulb itself, just one year later.

Farmers and ranchers were encroaching on land promised to the Bannock Tribe in 1878, and no one took the Tribe’s complaints seriously. The dispute turned into a war when hogs were found rooting in the camas fields. One can imagine the seething anger of the Bannocks when they saw pigs tearing up the plants that had been a staple for them for time beyond memory.

The Indians went on a rampage, stealing cattle and horses, attacking and burning a wagon train, and sinking the ferry at Glenn’s Ferry. The Bannocks joined up with Paiutes pillaging across southeastern Oregon. Troops pursued them and the Indians suffered a final defeat in the Blue Mountains, though small raiding parties trickled back into Idaho stirring up trouble well into the fall.

There’s a historical marker about the Bannock War on U.S. 20 near Hill City.

So, now we know there are two… Wait. There’s ANOTHER historical marker on Idaho 62 between Craigmont and Nez Perce that talks about THAT Camas Prairie. Lalia Boone, in her book Idaho Place Names, A Geographical Dictionary, says that “Camas as a place name occurs throughout Idaho,” and doesn’t even bother to count up all the prairies and creeks so named.

If you’re still confused just know that camas is a beautiful flower that has been a key part of the unwritten and written history of this place we call Idaho.

If you’re a fan of historical markers, you probably already stopped at the one part-way up the steep White Bird grade that marks the beginning of the Nez Perce War. The first shots in that months-long running battle were fired from the top of a low hill as the Indians created a diversion there that allowed Chief Joseph and his people, who were camped on the prairie above, to slip away from soldiers.

When we talk about Camas Prairie, we could be talking about that one. Or we could be talking about the other Camas Prairie near Fairfield. It wasn’t part of the Nez Perce War, but it was the site of a war over the edible bulb itself, just one year later.

Farmers and ranchers were encroaching on land promised to the Bannock Tribe in 1878, and no one took the Tribe’s complaints seriously. The dispute turned into a war when hogs were found rooting in the camas fields. One can imagine the seething anger of the Bannocks when they saw pigs tearing up the plants that had been a staple for them for time beyond memory.

The Indians went on a rampage, stealing cattle and horses, attacking and burning a wagon train, and sinking the ferry at Glenn’s Ferry. The Bannocks joined up with Paiutes pillaging across southeastern Oregon. Troops pursued them and the Indians suffered a final defeat in the Blue Mountains, though small raiding parties trickled back into Idaho stirring up trouble well into the fall.

There’s a historical marker about the Bannock War on U.S. 20 near Hill City.

So, now we know there are two… Wait. There’s ANOTHER historical marker on Idaho 62 between Craigmont and Nez Perce that talks about THAT Camas Prairie. Lalia Boone, in her book Idaho Place Names, A Geographical Dictionary, says that “Camas as a place name occurs throughout Idaho,” and doesn’t even bother to count up all the prairies and creeks so named.

If you’re still confused just know that camas is a beautiful flower that has been a key part of the unwritten and written history of this place we call Idaho.

Published on August 07, 2023 04:00

August 6, 2023

Lake Hazel had no Beach

Since my posts on Chicken Dinner Road and Protest Road, I’ve received several requests to tell how other roads got their names. I can’t research them all right away, but one did catch my attention. It was about Lake Hazel Road that runs from Maple Grove Road in Boise to S. Robinson Road in Nampa. The request wasn’t about how the road got its name. They wondered where the heck the lake was?

The answer is, there is no Lake Hazel, but there was once. Sort of.

Back in the early 1900s there was a move to create reservoirs to capture Boise River water for irrigation purposes. Potential water users contracted with David R. Hubbard, a local land owner, to excavate reservoirs called Painter Lake, Hubbard Lake (later Hubbard Reservoir), Kuna Lake, Watkins Lake, Catherine Lake, and Rawson Lake. These were to be connected by laterals. All except Rawson Lake were completed. In the meantime, the much larger Boise Project came along with the promise to bring irrigation to the valley. The lakes were abandoned because they would likely interfere with the Boise Project. Since they were not being used for water storage, all the "lakes" disappeared in later years, except for Hubbard Reservoir.

So, what does all this have to do with Lake Hazel? Painter Lake was renamed Lake Hazel at some point. Even with the new name it was fated to be a lake in name only, with no water in evidence.

Thanks to Madeline Kelley Buckendorf, who did the research on this for a National Register of Historic Places application I found from 2003.

The answer is, there is no Lake Hazel, but there was once. Sort of.

Back in the early 1900s there was a move to create reservoirs to capture Boise River water for irrigation purposes. Potential water users contracted with David R. Hubbard, a local land owner, to excavate reservoirs called Painter Lake, Hubbard Lake (later Hubbard Reservoir), Kuna Lake, Watkins Lake, Catherine Lake, and Rawson Lake. These were to be connected by laterals. All except Rawson Lake were completed. In the meantime, the much larger Boise Project came along with the promise to bring irrigation to the valley. The lakes were abandoned because they would likely interfere with the Boise Project. Since they were not being used for water storage, all the "lakes" disappeared in later years, except for Hubbard Reservoir.

So, what does all this have to do with Lake Hazel? Painter Lake was renamed Lake Hazel at some point. Even with the new name it was fated to be a lake in name only, with no water in evidence.

Thanks to Madeline Kelley Buckendorf, who did the research on this for a National Register of Historic Places application I found from 2003.

Published on August 06, 2023 04:00

August 5, 2023

No, Not that Hemingway

That beep, beep, beep you hear is the sound of me backing into this story. It’s about Hemingway Butte, which today is an off-highway vehicle play area managed by the Boise District Bureau of Land Management. It includes a popular trail system and steep hillsides where OHVs and motorbikes defy gravity for a few seconds courtesy of two-cycle engines.

Hemingway Butte is about three miles southwest of Walter’s Ferry, which itself is about 15 miles south of Nampa. Beep, beep, beep.

Walters Ferry wasn’t always called that. It became Walter’s Ferry when Lewellyn R. Walter bought out his partner’s share of the ferry business in 1886. Previous owners had been John Fruit, George Blankenbecker, John Morgan, Leonard Fuqa, a Mr. Boon, Samuel Neeley, Perry Munday, Robert Duncan, and Reese Miles. But, beep, beep, we must back up to Munday for this story, because the drama took place when it was called Munday’s Ferry.

It was at Munday’s Ferry that the stage came thundering up from the south in August of 1878, its driver mortally wounded. Indians were chasing the stage and directing bullets at it. Munday and three soldiers set across the river toward the embattled stage coach, while two other soldier remained on the north side of the Snake to provide cover fire.

The soldiers and Indians exchanged fire for several minutes, according to a report in the Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman, while the ferry landed and the wounded stagecoach driver “quietly kept his seat, and when the boat touched the bank drove the team up the grade from the river and asked for water.”

Dr. W.W. McKay was dispatched from Boise to care for the driver. He made the dusty, 30-mile trip by buggy in two and a half hours, only to find when he got there that William Hemingway had breathed his last minutes before.

William Hemingway was the name of the stagecoach driver, and the aforementioned butte was named in his honor, as it was near there that the Indian attack began. Hemingway was buried in Silver City beside his wife and two children who had gone before.

Hemingway Butte is about three miles southwest of Walter’s Ferry, which itself is about 15 miles south of Nampa. Beep, beep, beep.

Walters Ferry wasn’t always called that. It became Walter’s Ferry when Lewellyn R. Walter bought out his partner’s share of the ferry business in 1886. Previous owners had been John Fruit, George Blankenbecker, John Morgan, Leonard Fuqa, a Mr. Boon, Samuel Neeley, Perry Munday, Robert Duncan, and Reese Miles. But, beep, beep, we must back up to Munday for this story, because the drama took place when it was called Munday’s Ferry.

It was at Munday’s Ferry that the stage came thundering up from the south in August of 1878, its driver mortally wounded. Indians were chasing the stage and directing bullets at it. Munday and three soldiers set across the river toward the embattled stage coach, while two other soldier remained on the north side of the Snake to provide cover fire.

The soldiers and Indians exchanged fire for several minutes, according to a report in the Idaho Tri-Weekly Statesman, while the ferry landed and the wounded stagecoach driver “quietly kept his seat, and when the boat touched the bank drove the team up the grade from the river and asked for water.”

Dr. W.W. McKay was dispatched from Boise to care for the driver. He made the dusty, 30-mile trip by buggy in two and a half hours, only to find when he got there that William Hemingway had breathed his last minutes before.

William Hemingway was the name of the stagecoach driver, and the aforementioned butte was named in his honor, as it was near there that the Indian attack began. Hemingway was buried in Silver City beside his wife and two children who had gone before.

Published on August 05, 2023 04:00

August 4, 2023

Can You Trust a Message in a Bottle?

In the fall of 1893, W.E. Carlin, the son of Brig. Gen. W.P. Carlin, Commander of the department of the Columbia, Vancouver, Washington, gathered together some friends for a hunting party in the Bitterroots of Idaho. They hired a Post Falls woodsman named George Colgate to cook for their little expedition.

A.L.A. Himmelwright, a businessman from New York who was on the trip, would later write a book about it. The details he provided painted a picture of a well-outfitted expedition: 125 pounds of flour, 30 pounds of bacon, 40 pounds of salt pork, 20 pounds of beans, eight pounds of coffee, and on and on. He described the guns, including Carlin’s three-barreled weapon that had two 12-gauge shotgun bores side-by-side with a .32 rifle beneath.

The group got to Kendrick by train, where they gathered together the supplies, five saddle horses, five pack horses, a spaniel and two terriers, and set out for a hunt.

Six inches of snow fell on September 22. That concerned guide Martin Spencer. He figured it would only get deeper as they moved higher into the mountains. Carlin decided to push on despite the snow, and although their cook had become ill. George Colgate’s legs had swollen to the point where he could barely hobble around. Everyone else shared in cooking duties as his abilities waned.

In the days to come Colgate rallied, then got progressively worse. One day he couldn’t even stay on his horse. As more snow flew, members of the hunting party nursed the cook while he lay in a tent.

Fifty miles from anything like civilization the Carlin party found themselves in a desperate situation with snow blocking trails and a man who could not be moved on their hands. Colgate was so sick he couldn’t talk. The men debated what to do. Should they stick it out where they were and hope the weather would break? Should they send someone ahead to bring back a rescue party?

While they pondered, another storm struck. Food was running short. They had to get out of there.

Someone struck on the idea of building a raft to float down the Lochsa. They lashed together some logs with cord and wire and attached a long sweep with which to guide the contraption. Before setting out on the raft, Himmelwright would make a dark entry in his diary: “It is a case of trying to save five lives or sacrificing them to perform the last sad rites for Colgate.”

The men set out downriver, leaving their cook behind seemingly on death’s door.

Cutting the story short, the hunting party lost their raft in a rapid several miles downstream. They survived by shooting a few grouse, catching a few fish, and even eating one of their dogs before a rescue party found them on November 21.

And now the story gets strange.

The men of the party were well known, so the tale of their failure to return when expected and their ultimate rescue had been carried in many newspapers, including the New York Times, which also carried the story of the bottle.

What bottle? The one that was purportedly found in the Snake River by one Sam Ellis at Penewawi, some 60 miles below Lewiston. Inside the bottle was this note:

FOOT OF BITTER ROOT MOUNTAINS, Nov. 27.—I am alive and well. Tell them to come and get me as soon as any one finds this. I am 50 miles from civilization as near as I can tell. I am George Colgate, one of the lost Carlin party. My legs are better. I can walk some. Come soon. Take this to Kendrick, Idaho, and you will be liberally rewarded. My name is George Colgate, from Post Falls. This bottle came by me and I caught it and wrote these words to take me out. Direct this to St. Elmo hotel, Kendrick, Idaho.

GEORGE COLGATE

“Good bye, wife and children.”

The small bottle was corked and fastened to a piece of driftwood with a rag tied to it.

The writing on the note was compared to Colgate’s signature on a hotel register and “was found to be wonderfully close.”

Two relief parties set out to rescue Colgate in the coming months. Neither met with success. Meanwhile, Carlin was adamant that the note in the bottle was a fake designed to somehow extort money from him and ruin his reputation.

The note seems a little pat and the finding of the bottle incredible, so maybe Carlin was right. In any case, his reputation suffered. There was debate for decades about the ethics of leaving a man to die in the wilderness.

And die he did. On August 23, 1894, the remains of George Colgate were found about eight miles from the spot where he was said to have been abandoned. How did he get there along with a matchbox, some fishing line, and other personal articles? Had he rallied long enough to drag himself through the snow that far? Had he lived to write a message in a bottle?

A.L.A. Himmelwright, a businessman from New York who was on the trip, would later write a book about it. The details he provided painted a picture of a well-outfitted expedition: 125 pounds of flour, 30 pounds of bacon, 40 pounds of salt pork, 20 pounds of beans, eight pounds of coffee, and on and on. He described the guns, including Carlin’s three-barreled weapon that had two 12-gauge shotgun bores side-by-side with a .32 rifle beneath.

The group got to Kendrick by train, where they gathered together the supplies, five saddle horses, five pack horses, a spaniel and two terriers, and set out for a hunt.

Six inches of snow fell on September 22. That concerned guide Martin Spencer. He figured it would only get deeper as they moved higher into the mountains. Carlin decided to push on despite the snow, and although their cook had become ill. George Colgate’s legs had swollen to the point where he could barely hobble around. Everyone else shared in cooking duties as his abilities waned.

In the days to come Colgate rallied, then got progressively worse. One day he couldn’t even stay on his horse. As more snow flew, members of the hunting party nursed the cook while he lay in a tent.

Fifty miles from anything like civilization the Carlin party found themselves in a desperate situation with snow blocking trails and a man who could not be moved on their hands. Colgate was so sick he couldn’t talk. The men debated what to do. Should they stick it out where they were and hope the weather would break? Should they send someone ahead to bring back a rescue party?

While they pondered, another storm struck. Food was running short. They had to get out of there.

Someone struck on the idea of building a raft to float down the Lochsa. They lashed together some logs with cord and wire and attached a long sweep with which to guide the contraption. Before setting out on the raft, Himmelwright would make a dark entry in his diary: “It is a case of trying to save five lives or sacrificing them to perform the last sad rites for Colgate.”

The men set out downriver, leaving their cook behind seemingly on death’s door.

Cutting the story short, the hunting party lost their raft in a rapid several miles downstream. They survived by shooting a few grouse, catching a few fish, and even eating one of their dogs before a rescue party found them on November 21.

And now the story gets strange.

The men of the party were well known, so the tale of their failure to return when expected and their ultimate rescue had been carried in many newspapers, including the New York Times, which also carried the story of the bottle.

What bottle? The one that was purportedly found in the Snake River by one Sam Ellis at Penewawi, some 60 miles below Lewiston. Inside the bottle was this note:

FOOT OF BITTER ROOT MOUNTAINS, Nov. 27.—I am alive and well. Tell them to come and get me as soon as any one finds this. I am 50 miles from civilization as near as I can tell. I am George Colgate, one of the lost Carlin party. My legs are better. I can walk some. Come soon. Take this to Kendrick, Idaho, and you will be liberally rewarded. My name is George Colgate, from Post Falls. This bottle came by me and I caught it and wrote these words to take me out. Direct this to St. Elmo hotel, Kendrick, Idaho.

GEORGE COLGATE

“Good bye, wife and children.”

The small bottle was corked and fastened to a piece of driftwood with a rag tied to it.

The writing on the note was compared to Colgate’s signature on a hotel register and “was found to be wonderfully close.”

Two relief parties set out to rescue Colgate in the coming months. Neither met with success. Meanwhile, Carlin was adamant that the note in the bottle was a fake designed to somehow extort money from him and ruin his reputation.

The note seems a little pat and the finding of the bottle incredible, so maybe Carlin was right. In any case, his reputation suffered. There was debate for decades about the ethics of leaving a man to die in the wilderness.

And die he did. On August 23, 1894, the remains of George Colgate were found about eight miles from the spot where he was said to have been abandoned. How did he get there along with a matchbox, some fishing line, and other personal articles? Had he rallied long enough to drag himself through the snow that far? Had he lived to write a message in a bottle?

Published on August 04, 2023 04:00

August 3, 2023

Ferry Across that River

Ferries carried cargo in Idaho once, but they lost their apostrophes along the way

Quick, which is easier to build a boat or a bridge? If you were in Idaho Territory in the early 1860s the answer was usually a boat. If the boat regularly crossed from one side of a river and back again, you’d call it a ferry. There were many such ferries in early Idaho, and they’ve left their mark in enduring place names: Bonners Ferry, Glenns Ferry, Walters Ferry, Smiths Ferry, Ferry Butte, Ferry Creek. Just kidding about that last one. It was named after Rudolph Ferry who had a homestead there.

Perhaps a good measure of the importance of something is how quickly government jumps in to regulate it. Idaho Territory was created in 1863 and by 1864 there was a statute on the books regulating ferries and toll bridges. You couldn’t operate one without a license and you were told how much you could charge.

According to Idaho Session Laws, 1864, the folks operating, say, the Eagle Rock Ferry above what would become Idaho Falls could charge the following:

For a man and a horse, .50 Page

For a horse and a carriage, $3.00

For a wagon and two horses, or two oxen, $4.00

For each additional pair of horses or cattle, $1.00

For each animal with a pack, .50

For loose animals, other than sheep or hogs, .25

For sheep and hogs, each, .15

Saying that it cost 50 cents for a man and a horse to cross doesn’t tell the whole story. A dollar then would buy a lot more than a dollar now. A dollar in 1865 would be worth the equivalent of $14.65 in today’s buying power.

Ferries in early Idaho were often tethered to a cable that stretched across the river from bank to bank. Maintenance on ferries was a headache, and they sometimes broke loose, or got rammed by floating logs. In the long run, a bridge is better, so ferries were often replaced by bridges either at the same site or at a better bridge site.

Ferries always belonged to someone, and often were named after that person. That’s obvious. What isn’t so easy to understand is why the town names linked to ferries don’t have possessive apostrophes. Much to the chagrin of English students everywhere the U.S. Board of Geographic Names, the authority on naming conventions, rarely allows apostrophes. Here’s how they explain that in their manual.

“Apostrophes suggesting possession or association are discouraged within the body of a proper geographic name (Henrys Fork: not Henry’s Fork). The word or words that form a geographic name change their connotative function and together become a single denotative unit. They change from words having specific dictionary meaning to fixed labels used to refer to geographic entities. The need to imply possession or association no longer exists. Thus, we write “Jamestown” instead of “James’town” or even “Richardsons Creek” instead of “Richard’s son’s creek.” The whole name can be made possessive or associative with an apostrophe at the end as in “Rogers Point’s rocky shore.” Apostrophes may be used within the body of a geographic name to denote a missing letter (Lake O’ the Woods) or when they normally exist in a surname used as part of a geographic name (O’Malley Draw).”

Dandy. But back in the days when ferries were operating references to them usually used apostrophes, so writing today about Glenn’s Ferry or Glenns Ferry can be a judgement call. And you thought writing this blog was easy.

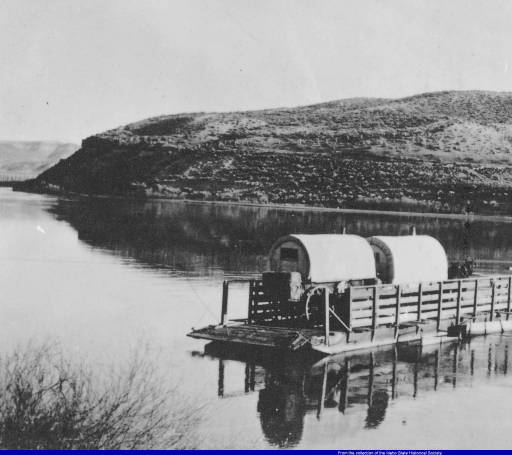

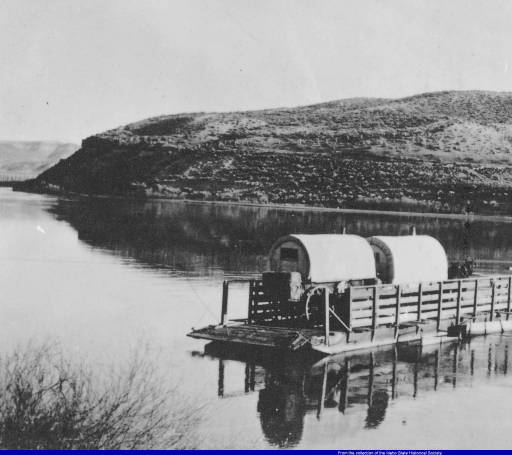

This is the Rosevear Ferry, from the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection. It operated at Glenn’s Ferry. Here it is taking a pair of sheep wagons across the Snake River.

This is the Rosevear Ferry, from the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection. It operated at Glenn’s Ferry. Here it is taking a pair of sheep wagons across the Snake River.

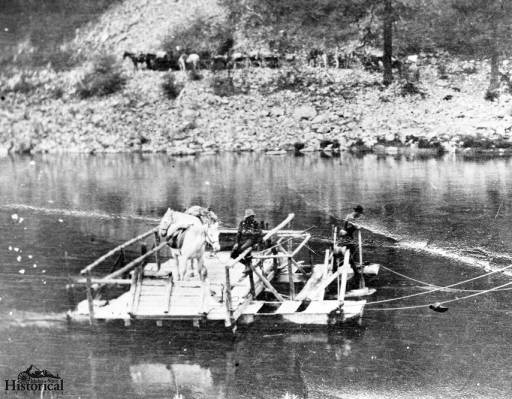

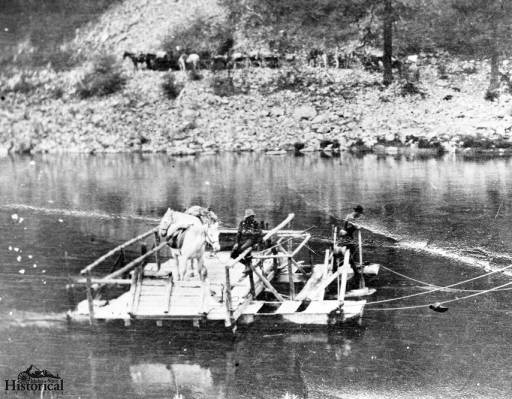

Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection, this photo is at Campbell’s Ferry, 12 miles from Dixie on the Salmon River, date unknown. There were rowboats on both sides of the platform to provide propulsion. It could carry three or four horses per trip.

Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection, this photo is at Campbell’s Ferry, 12 miles from Dixie on the Salmon River, date unknown. There were rowboats on both sides of the platform to provide propulsion. It could carry three or four horses per trip.

Quick, which is easier to build a boat or a bridge? If you were in Idaho Territory in the early 1860s the answer was usually a boat. If the boat regularly crossed from one side of a river and back again, you’d call it a ferry. There were many such ferries in early Idaho, and they’ve left their mark in enduring place names: Bonners Ferry, Glenns Ferry, Walters Ferry, Smiths Ferry, Ferry Butte, Ferry Creek. Just kidding about that last one. It was named after Rudolph Ferry who had a homestead there.

Perhaps a good measure of the importance of something is how quickly government jumps in to regulate it. Idaho Territory was created in 1863 and by 1864 there was a statute on the books regulating ferries and toll bridges. You couldn’t operate one without a license and you were told how much you could charge.

According to Idaho Session Laws, 1864, the folks operating, say, the Eagle Rock Ferry above what would become Idaho Falls could charge the following:

For a man and a horse, .50 Page

For a horse and a carriage, $3.00

For a wagon and two horses, or two oxen, $4.00

For each additional pair of horses or cattle, $1.00

For each animal with a pack, .50

For loose animals, other than sheep or hogs, .25

For sheep and hogs, each, .15

Saying that it cost 50 cents for a man and a horse to cross doesn’t tell the whole story. A dollar then would buy a lot more than a dollar now. A dollar in 1865 would be worth the equivalent of $14.65 in today’s buying power.

Ferries in early Idaho were often tethered to a cable that stretched across the river from bank to bank. Maintenance on ferries was a headache, and they sometimes broke loose, or got rammed by floating logs. In the long run, a bridge is better, so ferries were often replaced by bridges either at the same site or at a better bridge site.

Ferries always belonged to someone, and often were named after that person. That’s obvious. What isn’t so easy to understand is why the town names linked to ferries don’t have possessive apostrophes. Much to the chagrin of English students everywhere the U.S. Board of Geographic Names, the authority on naming conventions, rarely allows apostrophes. Here’s how they explain that in their manual.

“Apostrophes suggesting possession or association are discouraged within the body of a proper geographic name (Henrys Fork: not Henry’s Fork). The word or words that form a geographic name change their connotative function and together become a single denotative unit. They change from words having specific dictionary meaning to fixed labels used to refer to geographic entities. The need to imply possession or association no longer exists. Thus, we write “Jamestown” instead of “James’town” or even “Richardsons Creek” instead of “Richard’s son’s creek.” The whole name can be made possessive or associative with an apostrophe at the end as in “Rogers Point’s rocky shore.” Apostrophes may be used within the body of a geographic name to denote a missing letter (Lake O’ the Woods) or when they normally exist in a surname used as part of a geographic name (O’Malley Draw).”

Dandy. But back in the days when ferries were operating references to them usually used apostrophes, so writing today about Glenn’s Ferry or Glenns Ferry can be a judgement call. And you thought writing this blog was easy.

This is the Rosevear Ferry, from the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection. It operated at Glenn’s Ferry. Here it is taking a pair of sheep wagons across the Snake River.

This is the Rosevear Ferry, from the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection. It operated at Glenn’s Ferry. Here it is taking a pair of sheep wagons across the Snake River. Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection, this photo is at Campbell’s Ferry, 12 miles from Dixie on the Salmon River, date unknown. There were rowboats on both sides of the platform to provide propulsion. It could carry three or four horses per trip.

Courtesy of the Idaho State Historical Society digital collection, this photo is at Campbell’s Ferry, 12 miles from Dixie on the Salmon River, date unknown. There were rowboats on both sides of the platform to provide propulsion. It could carry three or four horses per trip.

Published on August 03, 2023 04:00

August 2, 2023

Idaho Loved Valentines

So, here’s a guy (me) who writes quirky little stories about Idaho history, writing about a guy who wrote quirky little stories about Idaho history. This post may eat its own tail.

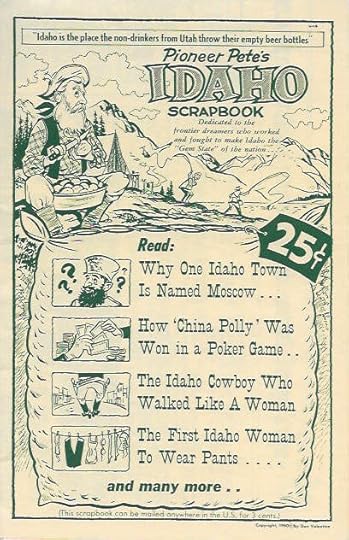

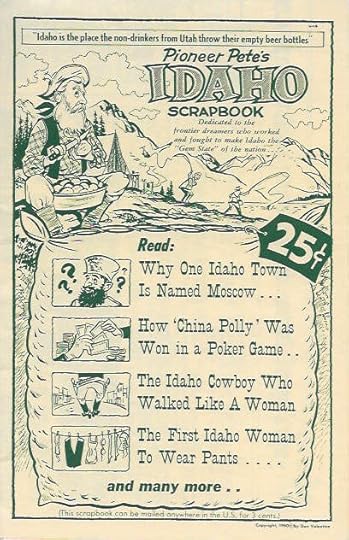

Dan Valentine wasn’t from Idaho, and he didn’t live here. Still, he was a purveyor of Idaho history, not in a scholarly sense, but in a storytelling sense. Valentine was a columnist for the Salt Lake Tribune for more than 30 years, retiring in 1980. In the 1950s and 60s, that paper was widely read in Southeastern Idaho. Enough so that Valentine included many humorous observations about the state.

Valentine published several books that grew out of his columns. They were often sold in restaurants and truck stops across Idaho and Utah. I ran across one of his publications recently while going through some family memorabilia. It’s a four-page newsletter quarter-folded into a book-sized pamphlet, called Pioneer Pete’s IDAHO Scrapbook, dated 1960. The amount of information he was able to squeeze in there is jaw-dropping. It included the story of Peg Leg Annie, a piece about Little Joe Monaghan, stories about Lana Turner, Polly Bemis, Ernest Hemingway, Diamondfield Jack, the lone parking meter in Murphy, and a dozen more. A better understanding of history has since put several of the stories into the apocryphal category, but at that time they were widely believed to be true.

Valentine’s material was featured on the Johnny Carson Show, as well as programs hosted by Tennessee Ernie Ford, Garry Moore, and Art Linkletter.

A taste from the pamphlet:

Cats were allegedly worth $10 each in Idaho City once, because of a mouse problem.

Boise (at that time) was said to boast the only wooden cigar store Indian factory in the world.

If the state of Idaho was flattened out it would be larger than Texas.

Valentine was once accused of being a bit chauvinistic in his columns, but he’s also the guy who once said "I don't know why women would want to give up complete superiority for mere equality."

Dan Valentine passed away in 1991 at age 73.

Dan Valentine wasn’t from Idaho, and he didn’t live here. Still, he was a purveyor of Idaho history, not in a scholarly sense, but in a storytelling sense. Valentine was a columnist for the Salt Lake Tribune for more than 30 years, retiring in 1980. In the 1950s and 60s, that paper was widely read in Southeastern Idaho. Enough so that Valentine included many humorous observations about the state.

Valentine published several books that grew out of his columns. They were often sold in restaurants and truck stops across Idaho and Utah. I ran across one of his publications recently while going through some family memorabilia. It’s a four-page newsletter quarter-folded into a book-sized pamphlet, called Pioneer Pete’s IDAHO Scrapbook, dated 1960. The amount of information he was able to squeeze in there is jaw-dropping. It included the story of Peg Leg Annie, a piece about Little Joe Monaghan, stories about Lana Turner, Polly Bemis, Ernest Hemingway, Diamondfield Jack, the lone parking meter in Murphy, and a dozen more. A better understanding of history has since put several of the stories into the apocryphal category, but at that time they were widely believed to be true.

Valentine’s material was featured on the Johnny Carson Show, as well as programs hosted by Tennessee Ernie Ford, Garry Moore, and Art Linkletter.

A taste from the pamphlet:

Cats were allegedly worth $10 each in Idaho City once, because of a mouse problem.

Boise (at that time) was said to boast the only wooden cigar store Indian factory in the world.

If the state of Idaho was flattened out it would be larger than Texas.

Valentine was once accused of being a bit chauvinistic in his columns, but he’s also the guy who once said "I don't know why women would want to give up complete superiority for mere equality."

Dan Valentine passed away in 1991 at age 73.

Published on August 02, 2023 04:00

August 1, 2023

The SS William E. Borah

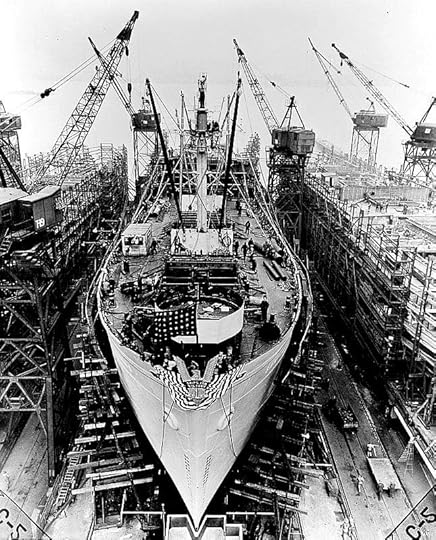

Following World War I, it became clear that America’s merchant marine fleet was becoming obsolete. In what would be a fortunate move prior to World War II, Congress passed the Merchant Marine Act of 1936. More than 2,700 mass-produced ships using pre-fabricated sections in their design, joined the fleet. They were officially called Liberty Ships. Famously, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, an aficionado of naval vessels, dubbed the ships “ugly ducklings.”

The Liberty Ships served their purpose going into the war, but it soon became apparent that they were too slow and too small to carry all the supplies needed for the war effort. The United States began a new program of shipbuilding in 1942. The faster, larger ships in this second wave were called Victory Ships.

On December 20, 1942, the Idaho Stateman announced that “Idaho’s victory ship, the William E. Borah, will slide down the ways at Portland, Ore., on Dec. 27.” Mary M. Borah, the widow of the late senator and Idaho’s Governor Chase Clark would be on hand to witness the launch.

Also invited to the ceremony were several Idaho school children who had won scrap-collecting contests. Though they probably didn’t collect enough scrap metal to build a ship, children from North Idaho and South Idaho met up in Portland for the event the day after Christmas.

The SS William E. Borah served the merchant fleet for 19 years before being scrapped in 1961, perhaps to serve again in some new form.

A liberty ship under construction at the Bethlehem-Fairfield Shipyards in Baltimore. Liberty ship. (2023, June 3). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liberty_ship

A liberty ship under construction at the Bethlehem-Fairfield Shipyards in Baltimore. Liberty ship. (2023, June 3). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liberty_ship  A typical Liberty Ship configuration.

A typical Liberty Ship configuration.

The Liberty Ships served their purpose going into the war, but it soon became apparent that they were too slow and too small to carry all the supplies needed for the war effort. The United States began a new program of shipbuilding in 1942. The faster, larger ships in this second wave were called Victory Ships.

On December 20, 1942, the Idaho Stateman announced that “Idaho’s victory ship, the William E. Borah, will slide down the ways at Portland, Ore., on Dec. 27.” Mary M. Borah, the widow of the late senator and Idaho’s Governor Chase Clark would be on hand to witness the launch.

Also invited to the ceremony were several Idaho school children who had won scrap-collecting contests. Though they probably didn’t collect enough scrap metal to build a ship, children from North Idaho and South Idaho met up in Portland for the event the day after Christmas.

The SS William E. Borah served the merchant fleet for 19 years before being scrapped in 1961, perhaps to serve again in some new form.

A liberty ship under construction at the Bethlehem-Fairfield Shipyards in Baltimore. Liberty ship. (2023, June 3). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liberty_ship

A liberty ship under construction at the Bethlehem-Fairfield Shipyards in Baltimore. Liberty ship. (2023, June 3). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liberty_ship  A typical Liberty Ship configuration.

A typical Liberty Ship configuration.

Published on August 01, 2023 04:00

July 31, 2023

The Movie Star Buried Near Priest Lake

It wasn’t unusual for me to be picking my way across the backs of downed giants, jumping little creeks, and seeking picturesque shafts of light streaming through the cedars. I’d done it many times along the shores of Priest Lake, looking for that picture that would transport the viewer to that same spot to experience my awe of the big trees.

I was the communication chief for the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation, and part of that job was to serve as photographer of the parks. I had my favorite vantage point in each park where I could catch a sunrise, or the certain shadow of a dune. At Priest Lake the cedar groves were difficult to capture; their enormity and the cathedral-like nature of the forest they formed did not easily fit into an eyepiece.

That day I found a newly downed cedar, roots pointing into the air, still clinging to chunks of earth that had served the tree for at least a century. I walked the trunk toward those roots and looked through them, down to the shallow hole they had left behind and to the grassy area just beyond. There was a familiar formation of rocks, 13 stones in the shape of a cross, placed years before at the foot of a much younger tree.

I knew at once what it was. This was a part of the park known as Shipman Point, named after Nell Shipman, silent movie star who had her own movie studio in these woods. She had likely placed those stones there herself, in memory of Tresore, her great Dane.

Tresore was a movie star himself. He had played a feature role in one of Shipman’s movies, Back to God’s Country, filmed in 1919 in Canada. Shipman adored animals and was an early advocate for their humane treatment in films. She had a menagerie with her at Priest Lake, including Brownie the Bear, Barney the Elk, cougar, deer, sled dogs, and others.

In July, 1923, someone poisoned many of those animals, including Tresore. Shipman always suspected that her landlord, to whom she owed money, had been the culprit. She mourned the loss of her Dane and memorialized him with these words: “Here lies Champion Great Dane Tresore, an artist, a soldier, and a gentleman. Killed July 17 by the cowardly hand of a human cur. He died as he lived, protecting his mistress and her property.”

What Shipman could not have known was that Tresore, in his death, played a huge part in the revival of interest in her movies some 60 years later. A BSU professor named Tom Trusky ran across an essay she had written about the poisoning of Tresore in the Idaho State Historical Society Archives. He decided to find out more about Shipman. That led him down a path on which he discovered and restored every movie she ever made, and oversaw the publication of Shipman’s autobiography. Interest in her work as a pioneer woman in films remains high today because of Tom’s efforts.

Park rangers at Priest Lake, and some locals, knew where Tresore’s grave was long before I stumbled across it, of course. For me, my personal discovery came just a few months after my friend Tom’s death. It was a quirk he would have appreciated. He would have called it “a little treat.” Nell Shipman with Tresore on the left. Tresore's grave marker on the right.

Nell Shipman with Tresore on the left. Tresore's grave marker on the right.

I was the communication chief for the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation, and part of that job was to serve as photographer of the parks. I had my favorite vantage point in each park where I could catch a sunrise, or the certain shadow of a dune. At Priest Lake the cedar groves were difficult to capture; their enormity and the cathedral-like nature of the forest they formed did not easily fit into an eyepiece.

That day I found a newly downed cedar, roots pointing into the air, still clinging to chunks of earth that had served the tree for at least a century. I walked the trunk toward those roots and looked through them, down to the shallow hole they had left behind and to the grassy area just beyond. There was a familiar formation of rocks, 13 stones in the shape of a cross, placed years before at the foot of a much younger tree.

I knew at once what it was. This was a part of the park known as Shipman Point, named after Nell Shipman, silent movie star who had her own movie studio in these woods. She had likely placed those stones there herself, in memory of Tresore, her great Dane.

Tresore was a movie star himself. He had played a feature role in one of Shipman’s movies, Back to God’s Country, filmed in 1919 in Canada. Shipman adored animals and was an early advocate for their humane treatment in films. She had a menagerie with her at Priest Lake, including Brownie the Bear, Barney the Elk, cougar, deer, sled dogs, and others.

In July, 1923, someone poisoned many of those animals, including Tresore. Shipman always suspected that her landlord, to whom she owed money, had been the culprit. She mourned the loss of her Dane and memorialized him with these words: “Here lies Champion Great Dane Tresore, an artist, a soldier, and a gentleman. Killed July 17 by the cowardly hand of a human cur. He died as he lived, protecting his mistress and her property.”

What Shipman could not have known was that Tresore, in his death, played a huge part in the revival of interest in her movies some 60 years later. A BSU professor named Tom Trusky ran across an essay she had written about the poisoning of Tresore in the Idaho State Historical Society Archives. He decided to find out more about Shipman. That led him down a path on which he discovered and restored every movie she ever made, and oversaw the publication of Shipman’s autobiography. Interest in her work as a pioneer woman in films remains high today because of Tom’s efforts.

Park rangers at Priest Lake, and some locals, knew where Tresore’s grave was long before I stumbled across it, of course. For me, my personal discovery came just a few months after my friend Tom’s death. It was a quirk he would have appreciated. He would have called it “a little treat.”

Nell Shipman with Tresore on the left. Tresore's grave marker on the right.

Nell Shipman with Tresore on the left. Tresore's grave marker on the right.

Published on July 31, 2023 04:00