Rick Just's Blog, page 49

August 29, 2023

A Boise School Ahead of its Time

When Amity School was built in southwest Boise, the design was ahead of its time. Only two other earth-sheltered schools were in existence in the US. And, if 50 years is the yardstick you use to measure what qualifies as a historical building—as many do—it is again ahead of its time. The Amity School is coming down this summer after 39 years of use.

When the Boise School District purchased 15 acres for a new elementary school in 1975, energy issues were on everyone’s mind. The Yom Kippur war had taken place two years earlier and Arab countries were embargoing oil to the United States in retaliation for our country’s assistance to Israel in that conflict. Oil prices quadrupled.

So the school district decided to build an energy efficient building. They needed voter approval, of course. Usually school bonds are set for a given amount of money, then the district designs to that amount and comes in at or under budget. Not this time. Voters knew exactly what they were voting on when they went to the polls to give the up or down on the Amity School Bond. The district had already called for designs and chosen the most expensive one, at $3.5 million. They sold the proposal to voters on the idea that this earth-sheltered school with solar panels providing hot water heat, would pay for itself in lower energy costs. They expected the extra construction costs to be paid back in 16 years, and the solar panels to pay for themselves in 11 years. The district was wrong. With ever-increasing energy costs, the payback time was about half that.

Most people thought of Amity School as that “underground” school. It wasn’t. The concrete outer walls were poured on site, above ground, and the inner walls were completed with concrete block. Then, they put pre-cast concrete beams across the whole thing to form a roof. Once all the concrete was in place, they pushed about two feet of dirt up onto the roof and angled it against the walls on all sides to provide added insulation. The plan was originally to let the kids spend recess on the roof, playing in the grass. Early drawings showed landscaping up there, but it never happened, perhaps because there was plenty of ground for recess around the school and perhaps because watering the roof would add extra cost and complication, potentially causing leaks. That is, more leaks than were destined to happen anyway.

Designers didn’t want the school to feel like a cave, so they designed it so that every classroom had a door to the outside and one good-sized window. Offices, the lunchroom, restrooms, the gym, and the library were in the center of the structure and without natural light, but every room was painted in light, bright colors to compensate.

When the school came on line in 1979, its innovative design made Time Magazine. That first year the energy costs of the school were 72-74 percent lower than other schools in the district of similar size.

Amity School could handle 788 kids from kindergarten to sixth grade in 26 classrooms. Thousands of Boise kids grew up as “Groundhogs” (the school mascot was Solar Sam).

But, everything has a lifespan, and Amity School reached the end of its days in 2018, replaced by a new school built right next door.

Why tear down an innovative building? Leaks, mostly. That sod and concrete roof never could keep water out. But the district has learned a lot from the school. Several other schools in Boise use earth sheltered walls (not roofs) and other innovative features first tried out at Amity.

By the way, the first Amity School was in what was then the Meridian School District. It was built in 1919 to serve students a few miles west of the current school. The original Amity School was named such (probably) because the word means friendship and goodwill. They built a road to the school, which became Amity Road. The original school was converted to a private residence in the early 1950s, but was recently torn down. The name still stuck for the road, though, which then got attached to the earth-sheltered school, built in 1978, and first occupied in 1979.

Early aerial photo of Amity Elementary. The building was a rectangle with ten entrances angling from it, providing some light to each classroom. The solar panels are clearly visible on the top of the roof in this shot. That center structure housed the mechanical room and gave a little extra height for the gym.

Early aerial photo of Amity Elementary. The building was a rectangle with ten entrances angling from it, providing some light to each classroom. The solar panels are clearly visible on the top of the roof in this shot. That center structure housed the mechanical room and gave a little extra height for the gym.

You can see the concrete roof beams in this interior picture of the gym. Note the cheery colors.

You can see the concrete roof beams in this interior picture of the gym. Note the cheery colors.

The school had two main entrances and eight other classroom entrances.

The school had two main entrances and eight other classroom entrances.

The roof and sloping outside walls were planted in native grasses. The steel cables strung up between the concrete entrances were to assure that motorcycle riders and four-wheel drive fans didn’t attempt to climb the school. The original intent was to make the roof part of the playground, but that never came about.

The roof and sloping outside walls were planted in native grasses. The steel cables strung up between the concrete entrances were to assure that motorcycle riders and four-wheel drive fans didn’t attempt to climb the school. The original intent was to make the roof part of the playground, but that never came about.

When the Boise School District purchased 15 acres for a new elementary school in 1975, energy issues were on everyone’s mind. The Yom Kippur war had taken place two years earlier and Arab countries were embargoing oil to the United States in retaliation for our country’s assistance to Israel in that conflict. Oil prices quadrupled.

So the school district decided to build an energy efficient building. They needed voter approval, of course. Usually school bonds are set for a given amount of money, then the district designs to that amount and comes in at or under budget. Not this time. Voters knew exactly what they were voting on when they went to the polls to give the up or down on the Amity School Bond. The district had already called for designs and chosen the most expensive one, at $3.5 million. They sold the proposal to voters on the idea that this earth-sheltered school with solar panels providing hot water heat, would pay for itself in lower energy costs. They expected the extra construction costs to be paid back in 16 years, and the solar panels to pay for themselves in 11 years. The district was wrong. With ever-increasing energy costs, the payback time was about half that.

Most people thought of Amity School as that “underground” school. It wasn’t. The concrete outer walls were poured on site, above ground, and the inner walls were completed with concrete block. Then, they put pre-cast concrete beams across the whole thing to form a roof. Once all the concrete was in place, they pushed about two feet of dirt up onto the roof and angled it against the walls on all sides to provide added insulation. The plan was originally to let the kids spend recess on the roof, playing in the grass. Early drawings showed landscaping up there, but it never happened, perhaps because there was plenty of ground for recess around the school and perhaps because watering the roof would add extra cost and complication, potentially causing leaks. That is, more leaks than were destined to happen anyway.

Designers didn’t want the school to feel like a cave, so they designed it so that every classroom had a door to the outside and one good-sized window. Offices, the lunchroom, restrooms, the gym, and the library were in the center of the structure and without natural light, but every room was painted in light, bright colors to compensate.

When the school came on line in 1979, its innovative design made Time Magazine. That first year the energy costs of the school were 72-74 percent lower than other schools in the district of similar size.

Amity School could handle 788 kids from kindergarten to sixth grade in 26 classrooms. Thousands of Boise kids grew up as “Groundhogs” (the school mascot was Solar Sam).

But, everything has a lifespan, and Amity School reached the end of its days in 2018, replaced by a new school built right next door.

Why tear down an innovative building? Leaks, mostly. That sod and concrete roof never could keep water out. But the district has learned a lot from the school. Several other schools in Boise use earth sheltered walls (not roofs) and other innovative features first tried out at Amity.

By the way, the first Amity School was in what was then the Meridian School District. It was built in 1919 to serve students a few miles west of the current school. The original Amity School was named such (probably) because the word means friendship and goodwill. They built a road to the school, which became Amity Road. The original school was converted to a private residence in the early 1950s, but was recently torn down. The name still stuck for the road, though, which then got attached to the earth-sheltered school, built in 1978, and first occupied in 1979.

Early aerial photo of Amity Elementary. The building was a rectangle with ten entrances angling from it, providing some light to each classroom. The solar panels are clearly visible on the top of the roof in this shot. That center structure housed the mechanical room and gave a little extra height for the gym.

Early aerial photo of Amity Elementary. The building was a rectangle with ten entrances angling from it, providing some light to each classroom. The solar panels are clearly visible on the top of the roof in this shot. That center structure housed the mechanical room and gave a little extra height for the gym. You can see the concrete roof beams in this interior picture of the gym. Note the cheery colors.

You can see the concrete roof beams in this interior picture of the gym. Note the cheery colors. The school had two main entrances and eight other classroom entrances.

The school had two main entrances and eight other classroom entrances. The roof and sloping outside walls were planted in native grasses. The steel cables strung up between the concrete entrances were to assure that motorcycle riders and four-wheel drive fans didn’t attempt to climb the school. The original intent was to make the roof part of the playground, but that never came about.

The roof and sloping outside walls were planted in native grasses. The steel cables strung up between the concrete entrances were to assure that motorcycle riders and four-wheel drive fans didn’t attempt to climb the school. The original intent was to make the roof part of the playground, but that never came about.

Published on August 29, 2023 04:00

August 28, 2023

Idaho's First White Settler

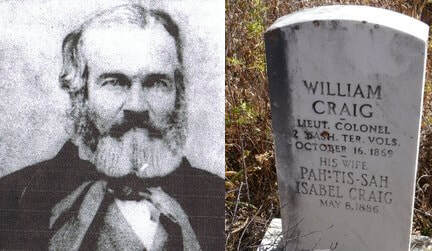

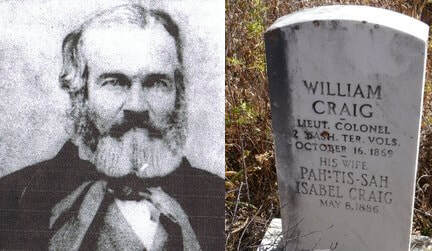

The name Idaho had not been invented in 1840 when William Craig became the first permanent settler within the bounds of what would become the 43rd state.

Born in Virginia in 1807, Craig was about 18 when he joined a group of trappers associated with the American Fur Company. In 1836 he and two other trappers established the Fort Davy Crockett trading post in what is now Colorado. When the fur trade there started to wane, he went west with his frontiersmen friends Joe Meek and Robert Newell. Those men ended up in the Willamette Valley of Oregon, but Craig, who had fallen in love with a Nez Perce woman, decided to settle in her homeland near present-day Lapwai.

Her family called his Nimiipuu wife Pahtissah, but Craig called her Isabel. The mission of Henry and Eliza Spalding was not far away. The Spaldings had established their mission in 1836, so theirs counts as the first white home in Idaho, but they left in 1847 after their missionary friends, Marcus and Narcissa Whitman were killed by Cayuse Indians at their mission near Walla Walla.

Spalding didn’t care much for Craig, but did value his ability to communicate with the Nez Perce. The Spaldings found the Craig home a handy refuge when they decided to abandon their mission.

Craig’s reputation for good relations with the natives served him well. He was an Indian agent to the Nez Perce and served the same role for a time at Fort Boise.

When the Nez Perce negotiated the treaty of 1848, they honored their friend by giving him 640 acres inside their new reservation.

Craig was not only the first permanent settler, but he was credited with coming up with the name of what would become Idaho. A lot of people have been credited with that, and it is widely disputed. In this case, it was frontiersman, poet, and newspaper editor Joaquin Miller who claimed William Craig knew it as the Indian word “E-dah-Hoe,” meaning “the light on the line of the mountains” In 1861. Click here for a more accepted etymology.

William Craig died in 1869 and is buried near his home in the Jacques Spur Cemetery, also called the Craig Cemetery. Craig Mountain Plateau, between the Snake, Salmon, and Clearwater rivers is named in his honor.

Born in Virginia in 1807, Craig was about 18 when he joined a group of trappers associated with the American Fur Company. In 1836 he and two other trappers established the Fort Davy Crockett trading post in what is now Colorado. When the fur trade there started to wane, he went west with his frontiersmen friends Joe Meek and Robert Newell. Those men ended up in the Willamette Valley of Oregon, but Craig, who had fallen in love with a Nez Perce woman, decided to settle in her homeland near present-day Lapwai.

Her family called his Nimiipuu wife Pahtissah, but Craig called her Isabel. The mission of Henry and Eliza Spalding was not far away. The Spaldings had established their mission in 1836, so theirs counts as the first white home in Idaho, but they left in 1847 after their missionary friends, Marcus and Narcissa Whitman were killed by Cayuse Indians at their mission near Walla Walla.

Spalding didn’t care much for Craig, but did value his ability to communicate with the Nez Perce. The Spaldings found the Craig home a handy refuge when they decided to abandon their mission.

Craig’s reputation for good relations with the natives served him well. He was an Indian agent to the Nez Perce and served the same role for a time at Fort Boise.

When the Nez Perce negotiated the treaty of 1848, they honored their friend by giving him 640 acres inside their new reservation.

Craig was not only the first permanent settler, but he was credited with coming up with the name of what would become Idaho. A lot of people have been credited with that, and it is widely disputed. In this case, it was frontiersman, poet, and newspaper editor Joaquin Miller who claimed William Craig knew it as the Indian word “E-dah-Hoe,” meaning “the light on the line of the mountains” In 1861. Click here for a more accepted etymology.

William Craig died in 1869 and is buried near his home in the Jacques Spur Cemetery, also called the Craig Cemetery. Craig Mountain Plateau, between the Snake, Salmon, and Clearwater rivers is named in his honor.

Published on August 28, 2023 04:00

August 27, 2023

Boise's Historical tie to Wake Island

The 1940 Fourth of July headline in The Idaho Statesman was about a contract local construction company Morrison-Knudsen had just won. “Boise Company Builds Bases,” the headline on page 3 read. No one knew how quickly that story would move to the front page, impacting Idaho families for years to come.

Harry Morrison, president of MK, had just returned from Washington, D.C. with the good news that the company had been awarded a substantial portion of construction under the National Defense Program, building air base facilities in the South Pacific. Midway and Wake Islands were mentioned in passing.

The story moved to page 2 in the Statesman on March 20, 1941, when it was announced that 150 workers, many of them from the Boise area, would sail from San Francisco for Wake Island. The company would be sending men “from engineers to dishwashers” to help build the air base.

Another page 2 article a couple of weeks later told that “several Canyon County young men (had) been given draft deferments to go to Wake Island where they would be employed by Morrison-Knudsen Construction.”

Over the course of the next few months there followed many articles about individual men on their way to build the air base in the South Pacific.

On September 19, 1941, the newspaper ran a story about the impressions of O.O. Kelso, from Caldwell. Headlined, “Idahoan Finds Wake Island ‘Crazy Place,’” it quoted Kelso as saying “rocks float; wood sinks; fish fly, and we have a bird here that runs but can’t fly.”

It got much crazier. On December 8, 1941, the day after that “Day of Infamy” at Pearl Harbor, there was a report the Japanese had taken Wake Island. This caused great concern in the Boise area, of course, because of the MK project there.

The family of 19-year-old Joe Goicoechea was on tenterhooks. He was among the civilian employees of MK on Wake Island. His dream job there—paying $120 a month—would turn into a nightmare as he and other Morrison-Knudsen employees took up arms alongside soldiers. They held off the attackers from December 8 until Christmas Eve, when he and hundreds of others were taken prisoner.

The Japanese forced the prisoners to build bunkers and fortifications against an American counter-attack. That flightless bird that O.O. Kelso mentioned, was hunted to extinction by the Japanese when the blockade by American forces brought their garrison to the point of starvation.

Goicoechea and others captured ended up spending 46 months in captivity, which included a starvation diet, inadequate clothing against the cold, and torture.

There were 1,100 Morrison-Knudson men on Wake Island on December 7, 1941. Only 700 made it home. Forty-seven died defending the island. Ninety-eight were executed by the Japanese. About a third of the men died in captivity under harsh conditions.

Joe Goicoechea made it back to Idaho. He lived until January, 2017. The Idaho Statesman reported upon his death that Goicoechea was thought to be the last of the Morrison-Knudson men who had experienced the battle on Wake Island and subsequent imprisonment to die.

The "98 Rock" is a memorial for the 98 U.S. civilian contract POWs who were forced by their Japanese captors to rebuild the airstrip as slave labor, then were blind-folded and killed by machine gun Oct. 5, 1943. An unidentified prisoner escaped, and chiseled "98 US PW 5-10-43" on a large coral rock near their mass grave, on Wilkes Island at the edge of the lagoon. The prisoner was recaptured and beheaded by the Japanese admiral, who was later convicted and executed for war crimes. (U.S. Air Force photo/Tech. Sgt. Shane A. Cuomo)

The "98 Rock" is a memorial for the 98 U.S. civilian contract POWs who were forced by their Japanese captors to rebuild the airstrip as slave labor, then were blind-folded and killed by machine gun Oct. 5, 1943. An unidentified prisoner escaped, and chiseled "98 US PW 5-10-43" on a large coral rock near their mass grave, on Wilkes Island at the edge of the lagoon. The prisoner was recaptured and beheaded by the Japanese admiral, who was later convicted and executed for war crimes. (U.S. Air Force photo/Tech. Sgt. Shane A. Cuomo)

Harry Morrison, president of MK, had just returned from Washington, D.C. with the good news that the company had been awarded a substantial portion of construction under the National Defense Program, building air base facilities in the South Pacific. Midway and Wake Islands were mentioned in passing.

The story moved to page 2 in the Statesman on March 20, 1941, when it was announced that 150 workers, many of them from the Boise area, would sail from San Francisco for Wake Island. The company would be sending men “from engineers to dishwashers” to help build the air base.

Another page 2 article a couple of weeks later told that “several Canyon County young men (had) been given draft deferments to go to Wake Island where they would be employed by Morrison-Knudsen Construction.”

Over the course of the next few months there followed many articles about individual men on their way to build the air base in the South Pacific.

On September 19, 1941, the newspaper ran a story about the impressions of O.O. Kelso, from Caldwell. Headlined, “Idahoan Finds Wake Island ‘Crazy Place,’” it quoted Kelso as saying “rocks float; wood sinks; fish fly, and we have a bird here that runs but can’t fly.”

It got much crazier. On December 8, 1941, the day after that “Day of Infamy” at Pearl Harbor, there was a report the Japanese had taken Wake Island. This caused great concern in the Boise area, of course, because of the MK project there.

The family of 19-year-old Joe Goicoechea was on tenterhooks. He was among the civilian employees of MK on Wake Island. His dream job there—paying $120 a month—would turn into a nightmare as he and other Morrison-Knudsen employees took up arms alongside soldiers. They held off the attackers from December 8 until Christmas Eve, when he and hundreds of others were taken prisoner.

The Japanese forced the prisoners to build bunkers and fortifications against an American counter-attack. That flightless bird that O.O. Kelso mentioned, was hunted to extinction by the Japanese when the blockade by American forces brought their garrison to the point of starvation.

Goicoechea and others captured ended up spending 46 months in captivity, which included a starvation diet, inadequate clothing against the cold, and torture.

There were 1,100 Morrison-Knudson men on Wake Island on December 7, 1941. Only 700 made it home. Forty-seven died defending the island. Ninety-eight were executed by the Japanese. About a third of the men died in captivity under harsh conditions.

Joe Goicoechea made it back to Idaho. He lived until January, 2017. The Idaho Statesman reported upon his death that Goicoechea was thought to be the last of the Morrison-Knudson men who had experienced the battle on Wake Island and subsequent imprisonment to die.

The "98 Rock" is a memorial for the 98 U.S. civilian contract POWs who were forced by their Japanese captors to rebuild the airstrip as slave labor, then were blind-folded and killed by machine gun Oct. 5, 1943. An unidentified prisoner escaped, and chiseled "98 US PW 5-10-43" on a large coral rock near their mass grave, on Wilkes Island at the edge of the lagoon. The prisoner was recaptured and beheaded by the Japanese admiral, who was later convicted and executed for war crimes. (U.S. Air Force photo/Tech. Sgt. Shane A. Cuomo)

The "98 Rock" is a memorial for the 98 U.S. civilian contract POWs who were forced by their Japanese captors to rebuild the airstrip as slave labor, then were blind-folded and killed by machine gun Oct. 5, 1943. An unidentified prisoner escaped, and chiseled "98 US PW 5-10-43" on a large coral rock near their mass grave, on Wilkes Island at the edge of the lagoon. The prisoner was recaptured and beheaded by the Japanese admiral, who was later convicted and executed for war crimes. (U.S. Air Force photo/Tech. Sgt. Shane A. Cuomo)

Published on August 27, 2023 04:00

August 26, 2023

The Snake River's Lost Falls

Though largely captured for most of the year to run turbines for power generation, Shoshone Falls does sometimes run wild in the spring, giving us a taste of what it once looked like. We can see the free-falling water at Mesa Falls anytime since it is the last large, unfettered falls on the Snake River. One mystery is what one waterfall, now lost to time and the production of power looked like.

Photos of American Falls prior to the dam and power plant construction are rare. There are several postcard photos showing the area of the falls shortly after the power plant and bridges were put in, giving some idea of what the original falls looked like. All that utilitarian construction is, charitably speaking, distracting.

There is an early lithograph of the American Falls. It is from a sketch by Charles Preuss and appeared in John Charles Fremont’s first report to Congress on his western explorations. Preuss was the cartographer for the expedition. His 1843 sketch of the falls is one of the earliest depictions of what is now Eastern Idaho.

The sketch shows a dramatic drop of water, split by a rock island. But one must take the accuracy with a grain of salt. As stated in the book One Hundred Years of Idaho Art, 1850-1950, by Sandy Harthorn and Kathleen Bettis, “Because Preuss was trained as a cartographer and not an artist, we can accept that his rather naïve drawings outline the land features rather than describe them as solid forms. Drawn in a stiff, awkward manner, this deep vista appears exaggerated and fanciful. The river drops from a flattened plain over the edge of an angulated precipice more illusory than real.”

Perhaps the reason photos of the falls before they were captured are difficult to come by is that they simply weren’t picturesque enough to attract a photographer. Postcards showing the railroad bridge going across American Falls.

Postcards showing the railroad bridge going across American Falls.  A close up of the power plant.

A close up of the power plant.

The Charles Preuss lithograph of the falls.

The Charles Preuss lithograph of the falls.

Photos of American Falls prior to the dam and power plant construction are rare. There are several postcard photos showing the area of the falls shortly after the power plant and bridges were put in, giving some idea of what the original falls looked like. All that utilitarian construction is, charitably speaking, distracting.

There is an early lithograph of the American Falls. It is from a sketch by Charles Preuss and appeared in John Charles Fremont’s first report to Congress on his western explorations. Preuss was the cartographer for the expedition. His 1843 sketch of the falls is one of the earliest depictions of what is now Eastern Idaho.

The sketch shows a dramatic drop of water, split by a rock island. But one must take the accuracy with a grain of salt. As stated in the book One Hundred Years of Idaho Art, 1850-1950, by Sandy Harthorn and Kathleen Bettis, “Because Preuss was trained as a cartographer and not an artist, we can accept that his rather naïve drawings outline the land features rather than describe them as solid forms. Drawn in a stiff, awkward manner, this deep vista appears exaggerated and fanciful. The river drops from a flattened plain over the edge of an angulated precipice more illusory than real.”

Perhaps the reason photos of the falls before they were captured are difficult to come by is that they simply weren’t picturesque enough to attract a photographer.

Postcards showing the railroad bridge going across American Falls.

Postcards showing the railroad bridge going across American Falls.  A close up of the power plant.

A close up of the power plant.

The Charles Preuss lithograph of the falls.

The Charles Preuss lithograph of the falls.

Published on August 26, 2023 04:00

August 25, 2023

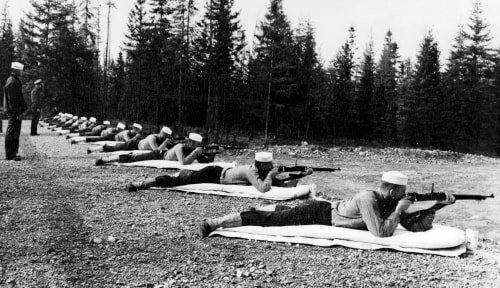

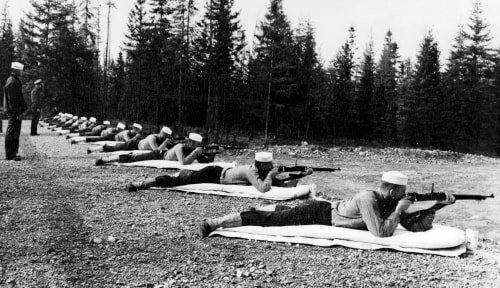

Taking Aim at Farragut

Time for one of our occasional then and now features.

Farragut Naval Training Station (FNTS) on the shores of Lake Pend Oreille, was a key facility in World War II. It went up fast. Construction began in March, 1942. By September of that year, the “boots” were already training.

The barracks, drill halls, and other facilities weren’t designed for long-term use, so few of them exist today. The only major building left on site from the base, the concrete brig, is a museum today at Farragut State Park.

One facility, though, is still in use. It’s not a building. It’s the station’s rifle range.

During rifle training, 100 men could fire their rifles at a time on the FNTS range. During the peak of training, about 12,000 rounds of ammunition were fired every day. Both the lead and the brass were salvaged and recycled into new ammunition.

The 50-, 100-, and 200-yard rifle ranges still exist and can be rented for practice and special events. They are operated by the Idaho Department of Fish and Game.

Farragut Naval Training Station (FNTS) on the shores of Lake Pend Oreille, was a key facility in World War II. It went up fast. Construction began in March, 1942. By September of that year, the “boots” were already training.

The barracks, drill halls, and other facilities weren’t designed for long-term use, so few of them exist today. The only major building left on site from the base, the concrete brig, is a museum today at Farragut State Park.

One facility, though, is still in use. It’s not a building. It’s the station’s rifle range.

During rifle training, 100 men could fire their rifles at a time on the FNTS range. During the peak of training, about 12,000 rounds of ammunition were fired every day. Both the lead and the brass were salvaged and recycled into new ammunition.

The 50-, 100-, and 200-yard rifle ranges still exist and can be rented for practice and special events. They are operated by the Idaho Department of Fish and Game.

Published on August 25, 2023 04:00

August 24, 2023

Presidential Roots in Idaho

Presidents Benjamin Harrison, Theodore Roosevelt, and William Howard Taft shared Idaho roots. No, none of them were born here, and none of them lived here, but they all put down roots.

It started with President Harrison. When he visited Idaho in 1891 he planted a red oak in front of the southeast corner of the Territorial Capitol. A rock sugar maple was the next presidential planting. That came about in 1903 when President Theodore Roosevelt visited Boise and put his tree next to Harrison’s red oak. Finally, President Taft planted an Ohio Buckeye (yes, he was from Ohio) next to Roosevelt’s maple.

The trees thrived. The first two planted lasted over 100 years. They came down in 2006, not from some disease but by the chainsaw of progress. That was the year excavation began for the new underground wings at the statehouse. They couldn’t work around the trees.

One Legislator with a sense of history and a woodworking hobby took it upon himself to preserve some of the history of the Idaho presidential trees. Then Rep. Max Black (R), District 15, saved much of the wood from the trees.

According to a story Royce Williams wrote for Idaho Public Television, saving the presidential wood was a challenge. Although Black had arranged with a contractor to secure the wood, when the chainsaws came out, it was a different contractor doing the work. Some fast talking saved the wood. Black then had to scramble to find a place to store it temporarily, and find a longer-term storage site where it could cure. Black secured a portable sawmill and 20 volunteers to slice up the trees. He located kilns in Emmett, Boise, and Meridian where he could dry the lumber.

After curing the wood for 18 months, Black began delivering it to wood carvers around the state. Each carver got enough wood to make something for themselves and a piece for public display. One of the carved art pieces is on display at the Boise Train Depot. Max Black did this one.

One of the carved art pieces is on display at the Boise Train Depot. Max Black did this one.

It started with President Harrison. When he visited Idaho in 1891 he planted a red oak in front of the southeast corner of the Territorial Capitol. A rock sugar maple was the next presidential planting. That came about in 1903 when President Theodore Roosevelt visited Boise and put his tree next to Harrison’s red oak. Finally, President Taft planted an Ohio Buckeye (yes, he was from Ohio) next to Roosevelt’s maple.

The trees thrived. The first two planted lasted over 100 years. They came down in 2006, not from some disease but by the chainsaw of progress. That was the year excavation began for the new underground wings at the statehouse. They couldn’t work around the trees.

One Legislator with a sense of history and a woodworking hobby took it upon himself to preserve some of the history of the Idaho presidential trees. Then Rep. Max Black (R), District 15, saved much of the wood from the trees.

According to a story Royce Williams wrote for Idaho Public Television, saving the presidential wood was a challenge. Although Black had arranged with a contractor to secure the wood, when the chainsaws came out, it was a different contractor doing the work. Some fast talking saved the wood. Black then had to scramble to find a place to store it temporarily, and find a longer-term storage site where it could cure. Black secured a portable sawmill and 20 volunteers to slice up the trees. He located kilns in Emmett, Boise, and Meridian where he could dry the lumber.

After curing the wood for 18 months, Black began delivering it to wood carvers around the state. Each carver got enough wood to make something for themselves and a piece for public display.

One of the carved art pieces is on display at the Boise Train Depot. Max Black did this one.

One of the carved art pieces is on display at the Boise Train Depot. Max Black did this one.

Published on August 24, 2023 04:00

August 23, 2023

Mile Marker Negative Point Seven

Harry Potter fans are familiar with platform 9 ¾ where students on their way to Hogwarts would walk through a wall to catch the train. Idaho has a trail marker on an old railroad route that is every bit as strange. It’s going to take a little history to explain how that came about.

At the peak of mining activity in Idaho’s Silver Valley, countless carloads of ore came out of the ground and travelled by rail between Mullan and Plummer, a 72-mile stretch of train tracks operated by the Burlington Northern Railroad in North Idaho. Those railroad cars were open so it was inevitable that dust and ore particles blew and jostled out onto the tracks beneath those steel wheels.

The railway crossed land owned by the Coeur d’Alene Tribe. Concerned that years of extraction of heavy metals had severely contaminated mining areas and the routes along which the ore travelled for processing, the Tribe sued Union Pacific Railroad and several mining companies to provide funding for a cleanup.

It became clear that cleaning up all the metal contaminants scattered along the old railway would be all but impossible.

In 1995 the federal government, Coeur d’Alene Tribe, and the State of Idaho agreed on a plan to cap the contaminated railroad bed to help contain the contamination. Under the plan the Coeur d’Alene Tribe and the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation share ownership and management of a paved pathway on top of the old Mullan to Plummer line. Union Pacific built the pathway and continues to provide major maintenance. The company also created an endowment fund to help pay for trail needs into the future.

This is a sow’s-ear-to-silk-purse story if ever there was one. The Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes now attracts tourists from all over the world bringing business to bike rental shops, ice cream sellers, restaurants, and lodging establishments along the smooth route of those rattly old trains. It winds across lakes, beside rivers and streams, and between stands of timber where bicyclists can ride without a thought about traffic.

It’s 72-miles long. Plus a tad more. After all the trail markers were in place, the Coeur d’Alene Tribe built a beautiful park in Plummer in honor of Tribal members who lost their lives fighting for the United States. A new section of pathway there leads to the Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes, and serves as the start of the trail on the western end. So, yes, there is a mile-marker negative point seven. Start your ride on the Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes there and you’ll find it every bit as magical as a Harry Potter adventure.

At the peak of mining activity in Idaho’s Silver Valley, countless carloads of ore came out of the ground and travelled by rail between Mullan and Plummer, a 72-mile stretch of train tracks operated by the Burlington Northern Railroad in North Idaho. Those railroad cars were open so it was inevitable that dust and ore particles blew and jostled out onto the tracks beneath those steel wheels.

The railway crossed land owned by the Coeur d’Alene Tribe. Concerned that years of extraction of heavy metals had severely contaminated mining areas and the routes along which the ore travelled for processing, the Tribe sued Union Pacific Railroad and several mining companies to provide funding for a cleanup.

It became clear that cleaning up all the metal contaminants scattered along the old railway would be all but impossible.

In 1995 the federal government, Coeur d’Alene Tribe, and the State of Idaho agreed on a plan to cap the contaminated railroad bed to help contain the contamination. Under the plan the Coeur d’Alene Tribe and the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation share ownership and management of a paved pathway on top of the old Mullan to Plummer line. Union Pacific built the pathway and continues to provide major maintenance. The company also created an endowment fund to help pay for trail needs into the future.

This is a sow’s-ear-to-silk-purse story if ever there was one. The Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes now attracts tourists from all over the world bringing business to bike rental shops, ice cream sellers, restaurants, and lodging establishments along the smooth route of those rattly old trains. It winds across lakes, beside rivers and streams, and between stands of timber where bicyclists can ride without a thought about traffic.

It’s 72-miles long. Plus a tad more. After all the trail markers were in place, the Coeur d’Alene Tribe built a beautiful park in Plummer in honor of Tribal members who lost their lives fighting for the United States. A new section of pathway there leads to the Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes, and serves as the start of the trail on the western end. So, yes, there is a mile-marker negative point seven. Start your ride on the Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes there and you’ll find it every bit as magical as a Harry Potter adventure.

Published on August 23, 2023 04:00

August 22, 2023

Paving those Muddy Streets

Pavement is a big part of life in Boise. There are more than 5,000 lane miles in Ada County, so you can’t go far without stepping on asphalt. It wasn’t always so.

Boise, founded in 1863, was content—maybe resigned—in the early days to dusty roads on dry days and mud bogs when it rained. In 1867 the Idaho Statesman expressed pleasure to see a “nice piece of pavement” in from of Mr. Blossom and Bloch, Miller & Co. The paper asked, “When shall we see a mile of it in Boise City?” I can provide the answer from my time machine: about 30 years.

“Pavement” could mean a lot of things, depending on the situation. We think of asphalt today, or maybe concrete. In 1874, there was some paving of gutters in front of C.W. Moore’s First National Bank. The Statesman welcomed that but cautioned that no one should get the idea of hauling gravel in to make a roadbed. “There is no road so heavy and unpleasant in dry weather as deep gravel and sand. Our season is dry for two-thirds to three-fourths of the year. Suppose we have mud one-third or a fourth of the year, it is better go bear a bad road one-fourth of the time than three-fourths.”

In 1880, the Statesman was lauding “handsome wood pavement” in front of the Valley Store. This brings up another point of confusion. “Pavement” could also refer to sidewalks, not just streets. Three years later, the paper was chiding a local restaurant for the badly dilapidated condition of the wooden pavement in front of its location.

One consequence of having dirt cum mud streets got notice in the Statesman in 1895. The paper cautioned gentlemen to watch were they stepped because of the high number of toads in the road, especially at night. In the same edition, the columnist was relieved to see smoother pavement in front of Dangel’s because the walkway had become a bad place for sober gentlemen.

Throughout the early years of Boise, it was up to merchants to provide improved footing for customers. The Falk Brothers put in stone pavement in front of their store in 1888.

A big improvement in paving technology came along in 1889. As the Statesman said, “It seems somewhat surprising that an artificial compound should prove more durable than, and every way preferable to natural stone for pavement; but it is nevertheless a fact that the pavements made from Portland Cement excel the natural stone pavement in every respect.”

That was the same year W.A. Culver began advertising his services in artificial stone paving and cement pavements.

In 1890, the Statesman—which was dead set against gravel a few years earlier—called for the use of pulverized stone for the streets around town. And who would do the pulverizing? “the ‘vags’ and other petty criminals (could) be put to work breaking stone for such purpose.”

Finally, on April 18, 1897, the headline read, “Street Paving District Definitely Settled.” Sections of Fifth, Sixth, Eighth, Ninth, Tenth, Twelfth, Idaho, Main, Grove, Bannock, Jefferson and some related alleys were to be paved. The city council would require the contractor to employ Boise laborers exclusively, excepting the foreman. No wages would be less than $2 a day. Councilors wrote up the specifications and determined it would cost $4.50 a front foot.

The Statesman editorialized in its April 21 edition that the council was making a mistake in planning to do so much street paving. They wanted an emphasis on sidewalks, not street paving.

Alas, by May 4, the Council had a change of heart. Only five blocks of Main Street, from Fifth to Tenth, would get pavement.

But by June, paving that single street was going so well that local property owners began clambering more extensions to the paving district.

In July, the paper ran one of its “As Others See Us” columns, a reprint of an article from the Caldwell Record. “Main Street is being paved and it is certainly to the credit of its citizens that they are determined to retrieve the city from the mud and dust to which it has been subject and to make the capital of Idaho worthy of the name Boise the beautiful. It is to be remarked that trees and lawns are now bright and green and free from dust, something never before known at mid-summer in Boise.”

Now, more than 130 years later, as residents know, all the streets of Boise are paved and one never encounters a rough spot or controversy about the streets. Paving Broadway Avenue in Boise, 1929. Idaho State Archives.

Paving Broadway Avenue in Boise, 1929. Idaho State Archives.

Boise, founded in 1863, was content—maybe resigned—in the early days to dusty roads on dry days and mud bogs when it rained. In 1867 the Idaho Statesman expressed pleasure to see a “nice piece of pavement” in from of Mr. Blossom and Bloch, Miller & Co. The paper asked, “When shall we see a mile of it in Boise City?” I can provide the answer from my time machine: about 30 years.

“Pavement” could mean a lot of things, depending on the situation. We think of asphalt today, or maybe concrete. In 1874, there was some paving of gutters in front of C.W. Moore’s First National Bank. The Statesman welcomed that but cautioned that no one should get the idea of hauling gravel in to make a roadbed. “There is no road so heavy and unpleasant in dry weather as deep gravel and sand. Our season is dry for two-thirds to three-fourths of the year. Suppose we have mud one-third or a fourth of the year, it is better go bear a bad road one-fourth of the time than three-fourths.”

In 1880, the Statesman was lauding “handsome wood pavement” in front of the Valley Store. This brings up another point of confusion. “Pavement” could also refer to sidewalks, not just streets. Three years later, the paper was chiding a local restaurant for the badly dilapidated condition of the wooden pavement in front of its location.

One consequence of having dirt cum mud streets got notice in the Statesman in 1895. The paper cautioned gentlemen to watch were they stepped because of the high number of toads in the road, especially at night. In the same edition, the columnist was relieved to see smoother pavement in front of Dangel’s because the walkway had become a bad place for sober gentlemen.

Throughout the early years of Boise, it was up to merchants to provide improved footing for customers. The Falk Brothers put in stone pavement in front of their store in 1888.

A big improvement in paving technology came along in 1889. As the Statesman said, “It seems somewhat surprising that an artificial compound should prove more durable than, and every way preferable to natural stone for pavement; but it is nevertheless a fact that the pavements made from Portland Cement excel the natural stone pavement in every respect.”

That was the same year W.A. Culver began advertising his services in artificial stone paving and cement pavements.

In 1890, the Statesman—which was dead set against gravel a few years earlier—called for the use of pulverized stone for the streets around town. And who would do the pulverizing? “the ‘vags’ and other petty criminals (could) be put to work breaking stone for such purpose.”

Finally, on April 18, 1897, the headline read, “Street Paving District Definitely Settled.” Sections of Fifth, Sixth, Eighth, Ninth, Tenth, Twelfth, Idaho, Main, Grove, Bannock, Jefferson and some related alleys were to be paved. The city council would require the contractor to employ Boise laborers exclusively, excepting the foreman. No wages would be less than $2 a day. Councilors wrote up the specifications and determined it would cost $4.50 a front foot.

The Statesman editorialized in its April 21 edition that the council was making a mistake in planning to do so much street paving. They wanted an emphasis on sidewalks, not street paving.

Alas, by May 4, the Council had a change of heart. Only five blocks of Main Street, from Fifth to Tenth, would get pavement.

But by June, paving that single street was going so well that local property owners began clambering more extensions to the paving district.

In July, the paper ran one of its “As Others See Us” columns, a reprint of an article from the Caldwell Record. “Main Street is being paved and it is certainly to the credit of its citizens that they are determined to retrieve the city from the mud and dust to which it has been subject and to make the capital of Idaho worthy of the name Boise the beautiful. It is to be remarked that trees and lawns are now bright and green and free from dust, something never before known at mid-summer in Boise.”

Now, more than 130 years later, as residents know, all the streets of Boise are paved and one never encounters a rough spot or controversy about the streets.

Paving Broadway Avenue in Boise, 1929. Idaho State Archives.

Paving Broadway Avenue in Boise, 1929. Idaho State Archives.

Published on August 22, 2023 04:00

August 21, 2023

Our First Female Treasurer

Idaho has a long history of women in the position of state treasurer. Julie Ellsworth (R) is Idaho’s current treasurer. Seven have held it previously, including, in reverse order, Lydia Justice Edwards (R), 1987-1998; Marjorie Ruth Moon (D), 1963-1986; Ruth Moon (D) (Marjorie’s mother), 1945-1946, and 1955-1959; Margaret Gilbert (R), 1952-1954; Lela D. Painter (R) (who died in office) 1947-1952; and Myrtle P. Enking (D), 1933-1944.

Enking was Idaho’s first female treasurer and the second female treasurer in the nation. Myrtle Powell graduated from high school in Avon, Illinois in 1898, and came to Idaho in 1909 to take a position as a bookkeeper at the Gooding Mercantile Company. She married William Enking in 1911. He passed away in 1913 leaving Myrtle with a son to raise.

Mrs. Enking was the first librarian of the Gooding Public Library and served as the Gooding County Auditor for 15 years before her successful run for state treasurer. In 1943, UPI Correspondent John Corlett called her “the greatest vote-getter in Idaho history.” There was speculation at that time that she might take on Congressman Henry Dworshak, but she did not. She was known for wearing tall hats, possibly because she stood only four foot eleven inches.

Myrtle Enking passed away in Boise in July, 1972 at the age of 92.

Enking was Idaho’s first female treasurer and the second female treasurer in the nation. Myrtle Powell graduated from high school in Avon, Illinois in 1898, and came to Idaho in 1909 to take a position as a bookkeeper at the Gooding Mercantile Company. She married William Enking in 1911. He passed away in 1913 leaving Myrtle with a son to raise.

Mrs. Enking was the first librarian of the Gooding Public Library and served as the Gooding County Auditor for 15 years before her successful run for state treasurer. In 1943, UPI Correspondent John Corlett called her “the greatest vote-getter in Idaho history.” There was speculation at that time that she might take on Congressman Henry Dworshak, but she did not. She was known for wearing tall hats, possibly because she stood only four foot eleven inches.

Myrtle Enking passed away in Boise in July, 1972 at the age of 92.

Published on August 21, 2023 04:00

August 20, 2023

Of Maniacs and Wampus Cats

There are 155 schools in the state that have mascots. I can’t name them all without a little help from my friend Google. You know who you are.

There are several unusual ones, i.e., the Bonneville Bees, the Malad Dragons, the American Falls Beavers, etc. The Soda Springs Cardinals? Really? Has anyone ever spotted one in Soda Springs?

According to Maxpreps.com, a website about high school sports, there are seven schools in Idaho that have unique mascot names. That is, no one else in the U.S. uses that mascot. They are the Orofino Maniacs (is anyone surprised?), the Kamiah Kubs (thanks to the spelling), the Kuna Kavemen (ditto), the Maranatha Christian Great Danes, the Cutthroats of the Community School in Sun Valley, the Shelley Russets, and the Camas County High School Mushers.

I would have thought the Clark Fork Wampus Cats might be unique. Nope. There are at least five other schools that use that name. The one in Conway, Arkansas has a claim to being unique among Wampus cats, though. Their mascot has six legs.

What is a Wampus cat? Clark Fork High School has its own legend. It’s also a half-dog, half-cat in Appalachian folklore. But I digress.

Back in Idaho we need to spotlight the Shelley Russets for their brave use of a vegetable as a mascot, albeit one wearing a crown. I couldn’t find another high school using a vegetable mascot, but Scottsdale Community College is proud of their Fighting Artichoke. There’s also a Fighting Okra at Delta State.

You will, no doubt, share your favorite mascot and/or vegetable observations.

The Orofino High School mascot which, according to boosters, has nothing to do with the nearby State Hospital North.

The Orofino High School mascot which, according to boosters, has nothing to do with the nearby State Hospital North.

There are several unusual ones, i.e., the Bonneville Bees, the Malad Dragons, the American Falls Beavers, etc. The Soda Springs Cardinals? Really? Has anyone ever spotted one in Soda Springs?

According to Maxpreps.com, a website about high school sports, there are seven schools in Idaho that have unique mascot names. That is, no one else in the U.S. uses that mascot. They are the Orofino Maniacs (is anyone surprised?), the Kamiah Kubs (thanks to the spelling), the Kuna Kavemen (ditto), the Maranatha Christian Great Danes, the Cutthroats of the Community School in Sun Valley, the Shelley Russets, and the Camas County High School Mushers.

I would have thought the Clark Fork Wampus Cats might be unique. Nope. There are at least five other schools that use that name. The one in Conway, Arkansas has a claim to being unique among Wampus cats, though. Their mascot has six legs.

What is a Wampus cat? Clark Fork High School has its own legend. It’s also a half-dog, half-cat in Appalachian folklore. But I digress.

Back in Idaho we need to spotlight the Shelley Russets for their brave use of a vegetable as a mascot, albeit one wearing a crown. I couldn’t find another high school using a vegetable mascot, but Scottsdale Community College is proud of their Fighting Artichoke. There’s also a Fighting Okra at Delta State.

You will, no doubt, share your favorite mascot and/or vegetable observations.

The Orofino High School mascot which, according to boosters, has nothing to do with the nearby State Hospital North.

The Orofino High School mascot which, according to boosters, has nothing to do with the nearby State Hospital North.

Published on August 20, 2023 04:00