Rick Just's Blog, page 50

August 19, 2023

Do you want fries with that? Tough.

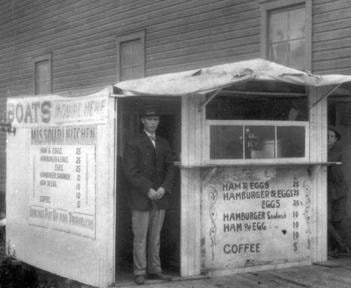

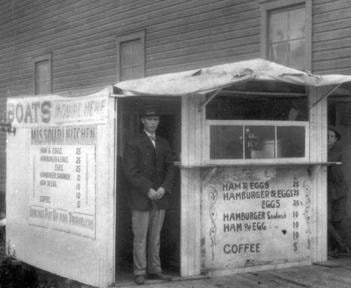

Hudson’s Hamburgers in Coeur d’Alene has been not selling fries with their hamburgers since 1907. And they do okay. You can get cheese on your hamburger, and you can order a pie for dessert. Just no fries.

Harley Hudson came to Coeur d’Alene from Brooklyn in 1905. The other Brooklyn. The one in Iowa. He sawed timber for a living for a couple of years, then thought the area could benefit from a good, basic burger. He built a rickety little stand out of canvas and boards and began selling hamburgers for a dime on the west end of the Idaho Hotel. He sold a lot of them. In 1910 he moved into a space next to the east end of the hotel that allowed him to have a counter and stools for a dozen customers.

When 1917 rolled around—the ten-year anniversary of Hudson’s Hamburgers—Harley had saved up enough money to buy a two-story brick building on the south side of Sherman Avenue, between Second and Third streets. He promptly named it the Hudson Building. The family operated the business from there until 1962 when they leased the spot to J.C. Penney and moved across the street to their present location, 207 E. Sherman Avenue.

Descendants of Harley Hudson still run the joint today. The menu is about the same as it was in 1907: plenty of burgers, no fries. They’ve been doing the burger thing so long and so well that there just isn’t much point in changing their business formulae. They’ve been named one of the top hamburger spots in the West by Sunset Magazine. The Wall Street Journal, USA Today, and Gourmet Magazine have all featured Hudson’s.

If you’re a history buff—and you probably are, if you’re reading this—stop in and take a look at the framed photos on the walls of big steamers and smaller boats that once plied the nearby waters. Maybe order a hamburger while you’re there.

Harley Hudson came to Coeur d’Alene from Brooklyn in 1905. The other Brooklyn. The one in Iowa. He sawed timber for a living for a couple of years, then thought the area could benefit from a good, basic burger. He built a rickety little stand out of canvas and boards and began selling hamburgers for a dime on the west end of the Idaho Hotel. He sold a lot of them. In 1910 he moved into a space next to the east end of the hotel that allowed him to have a counter and stools for a dozen customers.

When 1917 rolled around—the ten-year anniversary of Hudson’s Hamburgers—Harley had saved up enough money to buy a two-story brick building on the south side of Sherman Avenue, between Second and Third streets. He promptly named it the Hudson Building. The family operated the business from there until 1962 when they leased the spot to J.C. Penney and moved across the street to their present location, 207 E. Sherman Avenue.

Descendants of Harley Hudson still run the joint today. The menu is about the same as it was in 1907: plenty of burgers, no fries. They’ve been doing the burger thing so long and so well that there just isn’t much point in changing their business formulae. They’ve been named one of the top hamburger spots in the West by Sunset Magazine. The Wall Street Journal, USA Today, and Gourmet Magazine have all featured Hudson’s.

If you’re a history buff—and you probably are, if you’re reading this—stop in and take a look at the framed photos on the walls of big steamers and smaller boats that once plied the nearby waters. Maybe order a hamburger while you’re there.

Published on August 19, 2023 04:00

August 18, 2023

Making a Name Famous

If you’ve been hanging around Idaho for a few decades paying a little attention to who did what, you’ve run across the name Bowler from time-to-time. There’s Bruce Bowler who was a conservationist and attorney who pioneered the field of environmental law in Idaho. Drich (short for Aldrich) Bowler was an artist and inventor who hosted the 13-part Idaho Centennial series, produced by Idaho Public Television, "Proceeding on Through a Beautiful Country: A Television History of Idaho." Ned Bowler was a speech/language professor at the University of Colorado in Boulder.

But this is a story about their brother, Holden. Holden was an athlete, a military man, and a business man. He held a state record for high school track in Idaho, retired as a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army Reserve, ran a Denver ad agency, and taught environmental education. But it was his passion for singing that gave him a couple of interesting connections to noted contemporary figures.

While going to school at the University of Idaho in the early 1930s, Holden met Thomas Collins. They became good friends over the years, and Holden became godfather to Tom’s daughter Judy Collins, the well-known folksinger.

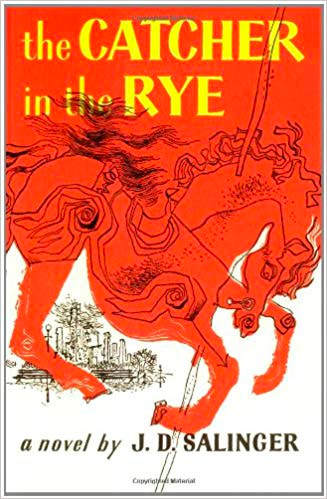

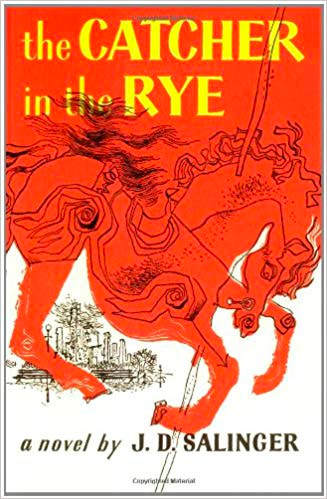

Singing took Holden to sea. He became the headline singer for a cruise line on a cruise to South America. He met a young man named Jerome who was staff on the ship. They became fast friends. The two toured the towns where the cruise ship stopped and shot the breeze. Jerome told Holden he was a writer. He liked Holden’s unusual first name and told him he would probably use it someday in a story.

When Jerome got around to using Holden’s name, the writer was going just by his first initials, J.D. J.D. Salinger. The author of Catcher in the Rye once wrote to Holden Bowler and said about the character who borrowed his name, “what you like about Holden (Caulfield) is taken from you, and what you don't like about him, I made up.”

Holden Bowler passed his passion for singing on to his daughter, Belinda Bowler, who I’ve heard called “Idaho folk music royalty.”

But this is a story about their brother, Holden. Holden was an athlete, a military man, and a business man. He held a state record for high school track in Idaho, retired as a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army Reserve, ran a Denver ad agency, and taught environmental education. But it was his passion for singing that gave him a couple of interesting connections to noted contemporary figures.

While going to school at the University of Idaho in the early 1930s, Holden met Thomas Collins. They became good friends over the years, and Holden became godfather to Tom’s daughter Judy Collins, the well-known folksinger.

Singing took Holden to sea. He became the headline singer for a cruise line on a cruise to South America. He met a young man named Jerome who was staff on the ship. They became fast friends. The two toured the towns where the cruise ship stopped and shot the breeze. Jerome told Holden he was a writer. He liked Holden’s unusual first name and told him he would probably use it someday in a story.

When Jerome got around to using Holden’s name, the writer was going just by his first initials, J.D. J.D. Salinger. The author of Catcher in the Rye once wrote to Holden Bowler and said about the character who borrowed his name, “what you like about Holden (Caulfield) is taken from you, and what you don't like about him, I made up.”

Holden Bowler passed his passion for singing on to his daughter, Belinda Bowler, who I’ve heard called “Idaho folk music royalty.”

Published on August 18, 2023 04:00

August 17, 2023

Hillside Letters

Time for a little audience participation. Get your cameras ready.

Have you ever given any thought to the big letter on the hills above your town? You know, the A above Arco, the B on Table Rock in Boise, the C on the hillside above Cambridge, etc.

According to Wikipedia, there are at least 35 letters on hillsides in Idaho, and maybe as many as 42. Most of them are the first letter of the town’s name, or a letter representing a local high school sports team. Franklin, the first town founded in Idaho Territory, has its big F (photo below), but above that are the numerals 1860 for the year it was founded.

Pocatello had a big concrete I on Red Hill representing Idaho State University for many years. It was placed there in 1927. Travelers going south on I-15 knew it as a Pocatello landmark. But in 2014 it was removed because of the risk of a hillside collapse due to heavy erosion. The fear was that the concrete initial might come crashing down on trail users below.

In the book Quintessential Boise, An Architectural Journey , by Charles Hummel, Tim Woodward, and others, they say the B on Table Rock above the Old Idaho Penitentiary, was placed there in 1931 by Ward Rolfe, Bob Krummes, Kenneth Robertson, and Simeon Coonrood, who were proud graduates of Boise High. As is the case with many such letters, the rocks often get a coat of paint to make them stand out.

Does your town have a letter? Post a picture in the comments section so we can all get a look. Do you have a story that goes along with the letter? An artifact of aliens, perhaps, or the site of your wedding proposal. Please share that, too.

Have you ever given any thought to the big letter on the hills above your town? You know, the A above Arco, the B on Table Rock in Boise, the C on the hillside above Cambridge, etc.

According to Wikipedia, there are at least 35 letters on hillsides in Idaho, and maybe as many as 42. Most of them are the first letter of the town’s name, or a letter representing a local high school sports team. Franklin, the first town founded in Idaho Territory, has its big F (photo below), but above that are the numerals 1860 for the year it was founded.

Pocatello had a big concrete I on Red Hill representing Idaho State University for many years. It was placed there in 1927. Travelers going south on I-15 knew it as a Pocatello landmark. But in 2014 it was removed because of the risk of a hillside collapse due to heavy erosion. The fear was that the concrete initial might come crashing down on trail users below.

In the book Quintessential Boise, An Architectural Journey , by Charles Hummel, Tim Woodward, and others, they say the B on Table Rock above the Old Idaho Penitentiary, was placed there in 1931 by Ward Rolfe, Bob Krummes, Kenneth Robertson, and Simeon Coonrood, who were proud graduates of Boise High. As is the case with many such letters, the rocks often get a coat of paint to make them stand out.

Does your town have a letter? Post a picture in the comments section so we can all get a look. Do you have a story that goes along with the letter? An artifact of aliens, perhaps, or the site of your wedding proposal. Please share that, too.

Published on August 17, 2023 04:00

August 16, 2023

Mechanical Donkeys

What would you call a locomotive without wheels? Loggers called them donkeys. About 20 Willamette donkeys, stationary steam engines that made rolls of steel cable spin, operated in the St. Joe drainage at one time. Their purpose was to drag logs off a mountain and into a holding pond where they could be readied for a trip downriver.

Fueled by wood or oil the donkeys turned drums around which 8,000 to 12,000 feet of cable fed. That meant that the donkey puncher (the guy who operated the machine) was usually out of sight of the choker (the man up the mountain rigging the cable around downed trees). To facilitate communication between the donkey puncher and the choker—who might be a mile and-a-half apart—they would run a line all the way back to the steam engine’s whistle. The line was typically in the hands of youngster yet too small for felling trees. He was called the whistle punk. He’d yank on the line a certain number of times when the choker would signal he was ready, or not ready, for the donkey puncher to start rolling in the cable and skidding the logs downhill.

A couple of these old donkeys are still around. The St. Joe Ranger District has built a short hiking trail to one at Marble Creek, called the Hobo Historical Trail, not far from St. Maries. They can give you information how to see it. If you don’t feel like hiking, you can also see one in St. Maries (below), a town very proud of its logging history. In 1958 they rescued one and brought it to a new home on Main in a city park dedicated to that history. You’ll see a statue of John Mullen in the same park, and learn a bit about that famous first road the captain built.

Fueled by wood or oil the donkeys turned drums around which 8,000 to 12,000 feet of cable fed. That meant that the donkey puncher (the guy who operated the machine) was usually out of sight of the choker (the man up the mountain rigging the cable around downed trees). To facilitate communication between the donkey puncher and the choker—who might be a mile and-a-half apart—they would run a line all the way back to the steam engine’s whistle. The line was typically in the hands of youngster yet too small for felling trees. He was called the whistle punk. He’d yank on the line a certain number of times when the choker would signal he was ready, or not ready, for the donkey puncher to start rolling in the cable and skidding the logs downhill.

A couple of these old donkeys are still around. The St. Joe Ranger District has built a short hiking trail to one at Marble Creek, called the Hobo Historical Trail, not far from St. Maries. They can give you information how to see it. If you don’t feel like hiking, you can also see one in St. Maries (below), a town very proud of its logging history. In 1958 they rescued one and brought it to a new home on Main in a city park dedicated to that history. You’ll see a statue of John Mullen in the same park, and learn a bit about that famous first road the captain built.

Published on August 16, 2023 04:00

August 15, 2023

Unceded Land

When a people have no written history, it is difficult to establish what happened where. Such is the case of Castle Rock near the Old Idaho Penitentiary in Boise. The Shoshone, Bannock, and Paiute tribes had an oral history about the place, which they called Eagle Rock. They had used the site, which includes a hot spring, for many years before the first white man came to the area. It was a place of healing and a place where they cared for their dead.

A developer in the late 1980s owned the land and thought it would be a great place for some high-end view properties. The tribes sued to stop the project.

The developer paid for an archaeological survey which found no trace of a gravesite. How could the Indians prove it was sacred ground when they didn’t have a written history?

No historian in Idaho at that time commanded more respect than Merle Wells. It was his opinion that the site had been used for many years by the tribes. He also had something written. An 1893 article in the Idaho Statesman described the “grinning skeletons” that had been uncovered near Table Rock and the Sho-Ban beads associated with the graves.

After six years of litigation over the issue all the parties were tired of fighting. The Boise City Council agreed to purchase a key piece of the Castle Rocks property for $500,000 to keep it from development. The developer made some concessions regarding rooflines and setbacks for the remainder of the project.

Today the area is known as Castle Rock Reserve and is managed by Boise City Parks and Recreation. The city has planted some 3000 native plants on the hillside. A hiking trail loops through the area, but well away from the sacred pools.

From the Boise Parks and Recreation website: “Betty Foster approached Boise's Parks & Recreation Department in 2006 with a project to raise the awareness of Castle Rock's historical significance. She raised funds and helped design the Castle Rock Reserve tribute stone near the Bacon Drive entrance. Betty is a dedicated wife, mother, former school librarian, active volunteer, and continues to share her knowledge with our community.

“The Castle Rock Reserve tribute stone is a poignant reminder that the rocks jetting out of the hillside that touch the sky are an important part of Idaho's Native American history. Visitors will appreciate the peaceful surroundings, expanse of open sky, views of the Boise Valley area, and the river that lies below. Let them also be filled with a sense of the past, present and future converging in a moment of time. Listen closely and you may hear a faint whisper on the breeze saying… tread gently for you are on sacred ground.”

A developer in the late 1980s owned the land and thought it would be a great place for some high-end view properties. The tribes sued to stop the project.

The developer paid for an archaeological survey which found no trace of a gravesite. How could the Indians prove it was sacred ground when they didn’t have a written history?

No historian in Idaho at that time commanded more respect than Merle Wells. It was his opinion that the site had been used for many years by the tribes. He also had something written. An 1893 article in the Idaho Statesman described the “grinning skeletons” that had been uncovered near Table Rock and the Sho-Ban beads associated with the graves.

After six years of litigation over the issue all the parties were tired of fighting. The Boise City Council agreed to purchase a key piece of the Castle Rocks property for $500,000 to keep it from development. The developer made some concessions regarding rooflines and setbacks for the remainder of the project.

Today the area is known as Castle Rock Reserve and is managed by Boise City Parks and Recreation. The city has planted some 3000 native plants on the hillside. A hiking trail loops through the area, but well away from the sacred pools.

From the Boise Parks and Recreation website: “Betty Foster approached Boise's Parks & Recreation Department in 2006 with a project to raise the awareness of Castle Rock's historical significance. She raised funds and helped design the Castle Rock Reserve tribute stone near the Bacon Drive entrance. Betty is a dedicated wife, mother, former school librarian, active volunteer, and continues to share her knowledge with our community.

“The Castle Rock Reserve tribute stone is a poignant reminder that the rocks jetting out of the hillside that touch the sky are an important part of Idaho's Native American history. Visitors will appreciate the peaceful surroundings, expanse of open sky, views of the Boise Valley area, and the river that lies below. Let them also be filled with a sense of the past, present and future converging in a moment of time. Listen closely and you may hear a faint whisper on the breeze saying… tread gently for you are on sacred ground.”

Published on August 15, 2023 04:00

August 14, 2023

Boise's 7th Street is Missing

If I were to say that 7th Street was the best-known street in Boise, you’d probably have to pause a minute to think just where that is and why some fool thinks it’s famous. You could find it between 6th and 8th streets, but the signs won’t be any help. They all say Capitol Boulevard.

It wasn’t always so.

Boise architect and president of the Boise Civic Improvement Association, Charles Wayland, first proposed turning 7th Street into a grand entrance boulevard to the City of Boise. That was in 1914. The proposal was almost an afterthought to his larger idea of channeling the Boise River. Wayland envisioned “saddle paths, footpaths, and parkways” following the course of the newly controlled river with residential areas opening up in what had been floodways. Does that sound a little like today’s Boise Greenbelt?

It wasn’t until 1925 that city officials began to get serious about building that grand entrance. That was the year the new Boise Depot was built, dominating the skyline on the bench directly in front of the capitol building. Those striking architectural icons just begged to have a mile-long boulevard between them. New York architects Carrere and Hastings who designed the mission–style depot pushed for a grand promenade to visually and physically connect the two buildings. A municipal bond made it all happen, with the completion of the Capitol Boulevard Bridge in 1931.

Keeping the view down Capitol Boulevard free from intruding buildings, business signs, and a tangle of traffic control devices has been a constant struggle ever since. It’s a struggle that hasn’t always been won (I’m looking at you, US Bank building), but keeping a vigilant eye on what happens on the boulevard is worth doing to preserve the city’s “grand promenade.”

It wasn’t always so.

Boise architect and president of the Boise Civic Improvement Association, Charles Wayland, first proposed turning 7th Street into a grand entrance boulevard to the City of Boise. That was in 1914. The proposal was almost an afterthought to his larger idea of channeling the Boise River. Wayland envisioned “saddle paths, footpaths, and parkways” following the course of the newly controlled river with residential areas opening up in what had been floodways. Does that sound a little like today’s Boise Greenbelt?

It wasn’t until 1925 that city officials began to get serious about building that grand entrance. That was the year the new Boise Depot was built, dominating the skyline on the bench directly in front of the capitol building. Those striking architectural icons just begged to have a mile-long boulevard between them. New York architects Carrere and Hastings who designed the mission–style depot pushed for a grand promenade to visually and physically connect the two buildings. A municipal bond made it all happen, with the completion of the Capitol Boulevard Bridge in 1931.

Keeping the view down Capitol Boulevard free from intruding buildings, business signs, and a tangle of traffic control devices has been a constant struggle ever since. It’s a struggle that hasn’t always been won (I’m looking at you, US Bank building), but keeping a vigilant eye on what happens on the boulevard is worth doing to preserve the city’s “grand promenade.”

Published on August 14, 2023 04:00

August 13, 2023

What's Your Number?

Time for another then and now feature.

At one time if you exchanged telephone numbers with someone, you were exchanging two letters and five numbers. I’m ancient enough to remember that the prefix in the Blackfoot area was SU5. The SU stood for Sunset. Firth’s FI6, stood for Fireside. That changed in the 1960s

An article in the May 18, 1961 Idaho Statesman announced the change to seven-digit numbers from the alphanumeric combinations. “Boise Main office number prefixes will be 342, 343, and 344, followed by four digits.” No doubt there was some grumbling about that, even though the digits were always there beneath the letters. Those Sunset 5, or SU5, prefixes in Blackfoot, for instance, simply became 785.

That 1961 article in the Statesman announced another major change. Idaho, along with every other state in the nation, was getting an area code, 208. More populous states got several, but Idaho could get along with just one. It was all to facilitate long-distance dialing.

There was little need for digits when Idaho’s first telephone was installed in Lewiston in 1878. There was just the one phone at the telegraph office, which according to the Lewiston Tribune did not operate well, perhaps due to “some defect in the instrument.” In 1879, John Halley’s telephone, the first in Boise, needed no number, either. It connected the stage office with his residence about a mile away. The first telephone exchange—a telephone system—in the state was started in Hailey in 1883.

So, that was then. This is now. Idaho has added a second area code. New telephone users in the state now get a 986 area code. Our growing population demands it. Today with the prevalence of cell phones and people keeping their area code when they move from another state, area codes are less and less an indicator of the location of a caller. The major grumbling point about having a second area code is that you must now use it whenever you dial any number, even if it’s across the street.

Dialing. There’s a word that could have been sent to history’s trashcan but remains in use today even though dials are now found mostly in museums.

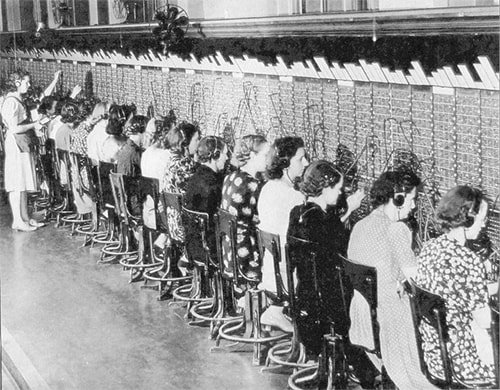

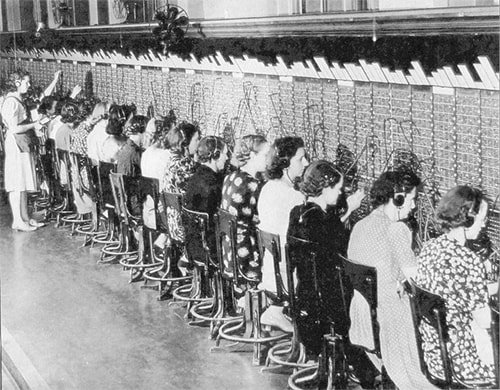

Early operators on the Pocatello exchange.

Early operators on the Pocatello exchange.

At one time if you exchanged telephone numbers with someone, you were exchanging two letters and five numbers. I’m ancient enough to remember that the prefix in the Blackfoot area was SU5. The SU stood for Sunset. Firth’s FI6, stood for Fireside. That changed in the 1960s

An article in the May 18, 1961 Idaho Statesman announced the change to seven-digit numbers from the alphanumeric combinations. “Boise Main office number prefixes will be 342, 343, and 344, followed by four digits.” No doubt there was some grumbling about that, even though the digits were always there beneath the letters. Those Sunset 5, or SU5, prefixes in Blackfoot, for instance, simply became 785.

That 1961 article in the Statesman announced another major change. Idaho, along with every other state in the nation, was getting an area code, 208. More populous states got several, but Idaho could get along with just one. It was all to facilitate long-distance dialing.

There was little need for digits when Idaho’s first telephone was installed in Lewiston in 1878. There was just the one phone at the telegraph office, which according to the Lewiston Tribune did not operate well, perhaps due to “some defect in the instrument.” In 1879, John Halley’s telephone, the first in Boise, needed no number, either. It connected the stage office with his residence about a mile away. The first telephone exchange—a telephone system—in the state was started in Hailey in 1883.

So, that was then. This is now. Idaho has added a second area code. New telephone users in the state now get a 986 area code. Our growing population demands it. Today with the prevalence of cell phones and people keeping their area code when they move from another state, area codes are less and less an indicator of the location of a caller. The major grumbling point about having a second area code is that you must now use it whenever you dial any number, even if it’s across the street.

Dialing. There’s a word that could have been sent to history’s trashcan but remains in use today even though dials are now found mostly in museums.

Early operators on the Pocatello exchange.

Early operators on the Pocatello exchange.

Published on August 13, 2023 04:00

August 12, 2023

A Horsethief and Escape Artist

It was the description of the man that really caught my eye: “He was a big, powerful Indian, five feet and nine inches in height, and weighed 171 pounds, all bone and muscle.” I happen to match the measurements to a tee, though you’d need to add a little flab to the description. Powerful as I am, I don’t think of myself as big. The average height of a man in 1906 was about 5’ 6”. Three inches over that, Jim Tannum was described as having “a magnificent physique.” I mean, now I’m blushing.

Even so, the writer for the Idaho Statesman who reported on Tannum in 1910 may have added a little spice to his physical description. It made the man sound more menacing, matching the description of his heredity: “Tannum possessed all the crafty cunning of the Indian, the vengeful instincts and the tenacity and magnificent physique of the redskin, together with the baser qualities of the degenerate white man.” Jim Tannum was one-quarter Umatilla, so he inherited the popular assumptions about Indians that settlers at the time had. Describing Indians as terrible people was a way of justifying the terrible things done to them to provide settlers with land.

And what terrible things had Tannum done? He was a drunk who stole horses. When he was captured, he became a persistent practitioner of the art of escape.

Tannum had been thieving livestock for some time in and around Washington County and across the river in Oregon, when he stole one horse too many in 1905. The horse belonged to a prominent citizen. Washington County Sheriff Robert Lansdon vowed to track down the thief. It took some weeks to catch up with Tannum in Meadows, which is just a few miles east of today’s town of New Meadows.

Tannum, who had bragged that he wouldn’t be taken alive, fought fiercely. He was no match for the five men who took him into custody. They hauled him to Weiser to await trial.

While in jail, Tannum began an intense study of the methods of escape. First, he rolled the metal from the sink in his cell into a club, with which he intended to overcome the sheriff. Lansdon became suspicious, searched Tannum’s cell, and found the weapon.

Next, the prisoner worked the steel support out of the instep of one of his shoes, somehow fashioning it into a saw. It took him two days to saw through the chain of his shackles. Tannum had complained bitterly about having to wear the cuffs. When he suddenly stopped complaining about it, the sheriff wondered why. The why was because Tannum didn’t want anyone to see that the severed chains were now held together by a shoelace.

Tannum was convicted of grand larceny and sentenced to five years in the pen. The two attempts at escape swayed the sheriff to bet Idaho State Penitentiary Warden Whitney a suit of clothes that the new inmate would get away within six months. Whitney took the bet. Landon won by a month and three days. Tannum escaped on April 7, 1906.

The prison escape came about while Tannum was working on a new wall around the women’s ward. When a guard turned away, the inmate slipped down the other side of the wall and crawled into an irrigation ditch. He followed the ditch until he was out of sight of the prison, and ran.

When Sheriff Landsdon heard about the escape, he “grinned and sent Whitney the measurements for that new suit,” according to the Statesman.

Landsdon stationed a deputy at the Weiser Bridge, thinking the escapee might come back to familiar territory. Tannum turned up riding a “borrowed” pony one night, intending to cross into Oregon. The deputy hollered for him to stop, but the horse thief had another plan. He spurred his horse into a run. The deputy fired buckshot at Tannum. It took his saddle horn off and left a couple of pellets in the Indian’s back, but he galloped back into Idaho.

Friends of Tannum got word to him that they had supplies and horses waiting for him in Oregon, if he could get across the Snake River. With the bridge under guard, the Indian dove into the water. The nearby posse spotted him and began to fire. He weaved, and dove, and weaved, and stroked, and dove his way across the river, evading bullets all the way. It was good enough to get away. For four years.

No posse ran Jim Tannum to ground. He caught himself. After spending some time sheepherding, he became bored. He rode into Burns, Oregon, had a few drinks, and announced that he was tired of the simple life and wanted some new trouble. He got it. Harney County Sheriff Richardson cuffed Tannum and took him to jail.

Idaho Penitentiary Deputy Warden Dan W. Ackley went to Burns to retrieve the escaped convict. While bending over to install an Oregon Boot, Ackley exposed his pistol to the prisoner. Tannum reached across Ackley’s back, grabbed the gun, and fired at Sheriff Richardson. He missed. Ackley grappled with the Indian, getting gut-shot in the process. The sheriff pulled his pistol and emptied it into Tannum, taking him out with six shots.

That was the end of Jim Tannum, and nearly so for Ackley. Early reports said he was dying, but he recovered well enough to live another 25 years.

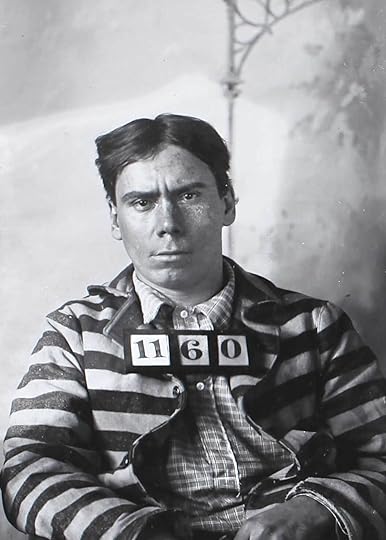

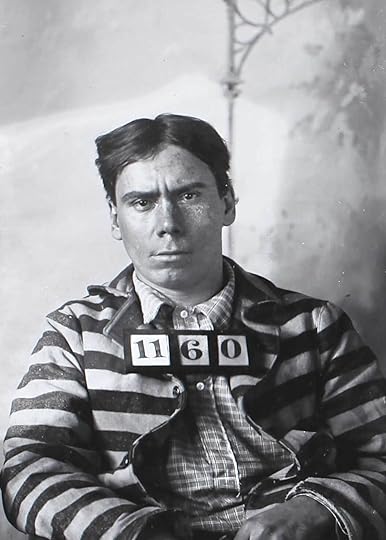

Booking photo oF Jim Tannum. Note that at this time the Idaho State Penitentiary was using a commercial photographer's screen as the background for booking photos. It added a cherry touch, I guess.

Booking photo oF Jim Tannum. Note that at this time the Idaho State Penitentiary was using a commercial photographer's screen as the background for booking photos. It added a cherry touch, I guess.

Even so, the writer for the Idaho Statesman who reported on Tannum in 1910 may have added a little spice to his physical description. It made the man sound more menacing, matching the description of his heredity: “Tannum possessed all the crafty cunning of the Indian, the vengeful instincts and the tenacity and magnificent physique of the redskin, together with the baser qualities of the degenerate white man.” Jim Tannum was one-quarter Umatilla, so he inherited the popular assumptions about Indians that settlers at the time had. Describing Indians as terrible people was a way of justifying the terrible things done to them to provide settlers with land.

And what terrible things had Tannum done? He was a drunk who stole horses. When he was captured, he became a persistent practitioner of the art of escape.

Tannum had been thieving livestock for some time in and around Washington County and across the river in Oregon, when he stole one horse too many in 1905. The horse belonged to a prominent citizen. Washington County Sheriff Robert Lansdon vowed to track down the thief. It took some weeks to catch up with Tannum in Meadows, which is just a few miles east of today’s town of New Meadows.

Tannum, who had bragged that he wouldn’t be taken alive, fought fiercely. He was no match for the five men who took him into custody. They hauled him to Weiser to await trial.

While in jail, Tannum began an intense study of the methods of escape. First, he rolled the metal from the sink in his cell into a club, with which he intended to overcome the sheriff. Lansdon became suspicious, searched Tannum’s cell, and found the weapon.

Next, the prisoner worked the steel support out of the instep of one of his shoes, somehow fashioning it into a saw. It took him two days to saw through the chain of his shackles. Tannum had complained bitterly about having to wear the cuffs. When he suddenly stopped complaining about it, the sheriff wondered why. The why was because Tannum didn’t want anyone to see that the severed chains were now held together by a shoelace.

Tannum was convicted of grand larceny and sentenced to five years in the pen. The two attempts at escape swayed the sheriff to bet Idaho State Penitentiary Warden Whitney a suit of clothes that the new inmate would get away within six months. Whitney took the bet. Landon won by a month and three days. Tannum escaped on April 7, 1906.

The prison escape came about while Tannum was working on a new wall around the women’s ward. When a guard turned away, the inmate slipped down the other side of the wall and crawled into an irrigation ditch. He followed the ditch until he was out of sight of the prison, and ran.

When Sheriff Landsdon heard about the escape, he “grinned and sent Whitney the measurements for that new suit,” according to the Statesman.

Landsdon stationed a deputy at the Weiser Bridge, thinking the escapee might come back to familiar territory. Tannum turned up riding a “borrowed” pony one night, intending to cross into Oregon. The deputy hollered for him to stop, but the horse thief had another plan. He spurred his horse into a run. The deputy fired buckshot at Tannum. It took his saddle horn off and left a couple of pellets in the Indian’s back, but he galloped back into Idaho.

Friends of Tannum got word to him that they had supplies and horses waiting for him in Oregon, if he could get across the Snake River. With the bridge under guard, the Indian dove into the water. The nearby posse spotted him and began to fire. He weaved, and dove, and weaved, and stroked, and dove his way across the river, evading bullets all the way. It was good enough to get away. For four years.

No posse ran Jim Tannum to ground. He caught himself. After spending some time sheepherding, he became bored. He rode into Burns, Oregon, had a few drinks, and announced that he was tired of the simple life and wanted some new trouble. He got it. Harney County Sheriff Richardson cuffed Tannum and took him to jail.

Idaho Penitentiary Deputy Warden Dan W. Ackley went to Burns to retrieve the escaped convict. While bending over to install an Oregon Boot, Ackley exposed his pistol to the prisoner. Tannum reached across Ackley’s back, grabbed the gun, and fired at Sheriff Richardson. He missed. Ackley grappled with the Indian, getting gut-shot in the process. The sheriff pulled his pistol and emptied it into Tannum, taking him out with six shots.

That was the end of Jim Tannum, and nearly so for Ackley. Early reports said he was dying, but he recovered well enough to live another 25 years.

Booking photo oF Jim Tannum. Note that at this time the Idaho State Penitentiary was using a commercial photographer's screen as the background for booking photos. It added a cherry touch, I guess.

Booking photo oF Jim Tannum. Note that at this time the Idaho State Penitentiary was using a commercial photographer's screen as the background for booking photos. It added a cherry touch, I guess.

Published on August 12, 2023 04:00

August 11, 2023

Buried Three Times

There is a lot of history buried in cemeteries, some of it a little quirky. The Oneida County Relic Preservation and Historical Society in Malad City has a story on their website, written by Sue Thomas that lives up to that label.

Twenty-five-year-old Benjamin Waldron was harvesting with a horse-drawn thresher in the fall of 1878. Somehow he slipped into the workings of the machine and got his leg caught. Locals pried him out and threw him in the back of a wagon, then set out for Logan, Utah as fast as the horses could run. They ran fast enough to save Waldron, but not his leg. Doctors in Logan had to amputate it.

It would be one of the worst puns I’ve ever come up with to say that Waldron was attached to his leg, so I’ll skip that. Let’s just say he was fond of it. He asked that the leg be buried in the Samaria Cemetery, complete with its own headstone. His friends did that, and we have the picture below as evidence. The—well, we can’t call it a headstone, can we?—marker is engraved with the words “B.W. October 30, 1878.”

Though his wishes had been carried out, Ben Waldron wasn’t quite satisfied. He suffered with pain for weeks after his leg was interred. He couldn’t get it out of his head that his appendage was twisted somehow in its resting place, and that was causing his pain. Humoring him once again, Ben’s friends dug up the leg. They reported to him that, yes, it had been twisted but they had buried it again in a more comfortable pose.

Waldron felt better after that and eventually adjusted to life with just one leg. He became a businessman in later years. We don’t know much more about him, except that he died in 1914 and is buried in the same cemetery, albeit not near his resting leg.

The two gravestones of Ben Waldron.

The two gravestones of Ben Waldron.

Twenty-five-year-old Benjamin Waldron was harvesting with a horse-drawn thresher in the fall of 1878. Somehow he slipped into the workings of the machine and got his leg caught. Locals pried him out and threw him in the back of a wagon, then set out for Logan, Utah as fast as the horses could run. They ran fast enough to save Waldron, but not his leg. Doctors in Logan had to amputate it.

It would be one of the worst puns I’ve ever come up with to say that Waldron was attached to his leg, so I’ll skip that. Let’s just say he was fond of it. He asked that the leg be buried in the Samaria Cemetery, complete with its own headstone. His friends did that, and we have the picture below as evidence. The—well, we can’t call it a headstone, can we?—marker is engraved with the words “B.W. October 30, 1878.”

Though his wishes had been carried out, Ben Waldron wasn’t quite satisfied. He suffered with pain for weeks after his leg was interred. He couldn’t get it out of his head that his appendage was twisted somehow in its resting place, and that was causing his pain. Humoring him once again, Ben’s friends dug up the leg. They reported to him that, yes, it had been twisted but they had buried it again in a more comfortable pose.

Waldron felt better after that and eventually adjusted to life with just one leg. He became a businessman in later years. We don’t know much more about him, except that he died in 1914 and is buried in the same cemetery, albeit not near his resting leg.

The two gravestones of Ben Waldron.

The two gravestones of Ben Waldron.

Published on August 11, 2023 04:00

August 10, 2023

The Tolo Lake Mammoths

Tolo Lake, near Grangeville, was in the news in the fall of 1994 when the Idaho Department of Fish and Game was deepening the drained lake to provide for better fishing. Fish and Game was hoping to take out a dozen feet of silt so that it could better support fish and waterfowl. What they found during the excavation was neither fish nor fowl. It was something much, much larger.

Tolo Lake, which is about 36 acres, was a rendezvous point for the Nez Perce, or nimí·pu, for many years, including at the start of what became the Nez Perce War. Digging there could help wildlife, sure, but it could also shed light on the Tribe’s history. But when the first bone was exposed it was clearly not an artifact of the Nez Perce occupation of the site. It was a leg bone 4 ½ feet tall. Its discovery quickly piqued the interest of archeologists, so scientists from the Nez Perce National Forest, Idaho State Historical Society, University of Idaho, and the Idaho Natural History Museum descended on the site where it was quickly determined that these were the bones of mammoths.

Mammoths were not called that for nothing. They weighed 10-15,000 pounds and stood about 14 feet at the shoulder. They were alive in North America as recently as 4,500 to 12,500 years ago, meaning they may have been familiar to the first people on the continent.

The dig exposed the bones of three mammoths and an ancient bison skull. The longest tusk discovered was measured at 16 feet. One of the tusks is on display at the Bicentennial Museum in Grangeville. The town also boasts a mammoth skeleton replica in an interpretive exhibit next to the Grangeville Chamber of Commerce office.

Tolo Lake, which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2011, was named for a Nez Perce woman who alerted settlers of the rampage that started the Nez Perce War. Tolo Lake Mammoth replica.

Tolo Lake Mammoth replica.  Tolo Lake.

Tolo Lake.

Tolo Lake, which is about 36 acres, was a rendezvous point for the Nez Perce, or nimí·pu, for many years, including at the start of what became the Nez Perce War. Digging there could help wildlife, sure, but it could also shed light on the Tribe’s history. But when the first bone was exposed it was clearly not an artifact of the Nez Perce occupation of the site. It was a leg bone 4 ½ feet tall. Its discovery quickly piqued the interest of archeologists, so scientists from the Nez Perce National Forest, Idaho State Historical Society, University of Idaho, and the Idaho Natural History Museum descended on the site where it was quickly determined that these were the bones of mammoths.

Mammoths were not called that for nothing. They weighed 10-15,000 pounds and stood about 14 feet at the shoulder. They were alive in North America as recently as 4,500 to 12,500 years ago, meaning they may have been familiar to the first people on the continent.

The dig exposed the bones of three mammoths and an ancient bison skull. The longest tusk discovered was measured at 16 feet. One of the tusks is on display at the Bicentennial Museum in Grangeville. The town also boasts a mammoth skeleton replica in an interpretive exhibit next to the Grangeville Chamber of Commerce office.

Tolo Lake, which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2011, was named for a Nez Perce woman who alerted settlers of the rampage that started the Nez Perce War.

Tolo Lake Mammoth replica.

Tolo Lake Mammoth replica.  Tolo Lake.

Tolo Lake.

Published on August 10, 2023 04:00