Peter Cameron's Blog, page 12

May 3, 2020

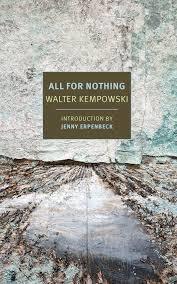

All for Nothing by Walter Kempowski, translated by Anthea...

All for Nothing by Walter Kempowski, translated by Anthea Bell

NYRB, 2018 (originally published Germany in 2006)

Sigrid Nunez recommended this book to me at one of our lunches last fall and I immediately went to 3 Lives bookshop and bought it. Soon thereafter Afterwords, the book club I belong to, decided to read it, and we were scheduled to discuss it on March 17, but had to postpone our meeting due to the Covid-1919 pandemic which resulted in social distancing.

All for Nothing is set in a large manor house outside a small village in East Prussia. The year is 1945. The Russians are advancing from the east and a large part of the population is fleeing westward, but the von Globigs, the family in the Manor House, seem unable to to make a decision about whether to flee or stay.

All for Nothing is set in a large manor house outside a small village in East Prussia. The year is 1945. The Russians are advancing from the east and a large part of the population is fleeing westward, but the von Globigs, the family in the Manor House, seem unable to to make a decision about whether to flee or stay.

The family consists of Katherina; the beautiful, introverted, and depressed mother; her twelve-year-old son, Peter; Auntie, a distant relative, a spinster who runs the estate in exchange for room and board, some pocket money, and grudging affection. Two resentful Ukranian maids and a Polish manservant complete the household. The father, Eberhard, is serving as an officer in the German army in Italy. During the final weeks the family remains in their beloved homestead various refugees are quartered, officially or secretly, in the house. The presence of these strangers force familial secrets and strains into the open, resulting in inevitable flight and tragedy. The concluding chapters harrowingly describe the plight of the family as they join the mass doomed exodus west. By focussing on the family's intimate lives during a time of tremendous public upheaval, Kempowski succeeds in telling a riveting story about the personal effects of war. He writes with brutal and unsentimental honesty, and reading the book is painful and upsetting. It was especially difficult to read this book during this period, for its constant sense of menace and imminent doom seem too close for comfort.

April 26, 2020

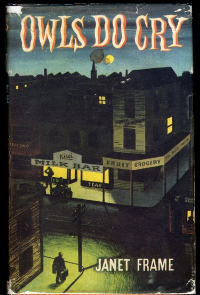

Owls Do Cry by Janet Frame

(George Brazilier, 1996; orig...

Owls Do Cry by Janet Frame

(George Brazilier, 1996; originally published by Brazilier in 1960)

Pegasus Press, New Zealand, 1957; cover illustration by Dennis Beytagh

It's been a long time since I've read a book as brilliant and creative and disturbing as Owls Do Cry. I have known about Janet Frame for a very long time, but never had a good sense of her work and never read anything by her until now. I wonder why that is? It seems odd that no one has recommended this extraordinary writer to me and urged me to read her work.

Owls Do Cry is Frame's first novel (her first book, a collection of short stories, was awarded a prize days before she was scheduled to undergo a lobotomy, which was cancelled because of the news). It is the story of the gradual but inexorable deterioration of the Withers family. They live (in New Zealand) in dirt and poverty and there seems to be no way for any of them to advance in the world. One one daughter manages to escape destruction by marrying a successful man and heartlessly distancing herself, emotionally and geographically, from her siblings and parents.

The novel follows the children from early childhood to middle age. Their lives are terrible and they seem helpless to change anything. There is only violence and madness and family, all held together with a heartbreaking ineffectual love.

Frame is a brilliant and exciting stylist: her prose is inventive and unbound by convention; even the placement of the words on the page is often surprising and poetic. She writes with the freedom and passion of Joyce but with less ego and ambition, and her prose subsequently outreaches itself, so that one reads with, rather than against, the current.

A thrillingly and uniquely good book.

Guard Your Daughters by Diana Tutton

(Persophone, 2017; ...

Guard Your Daughters by Diana Tutton

(Persophone, 2017; originally published by Chatto & Windus in 1953)

Guard Your Daughters is an interesting and engaging book. In many ways, it's familiar: an eccentric British family, the Harveys, have too many daughter -- 5 in this case: Pandora, Thisbe, Morgan, Cressida, and Teresa (the mother lost interest in naming after the fourth daughter so poor Teresa was named by her less romantic father). The Harveys life in self-elected poverty in a huge house outside of a small village. Mr. Harvey is a very successful writer of mysteries, and his wife is a beautiful but extremely fragile woman who must be constantly catered to, cosseted, and comforted, for she has a great fear of losing any of her daughters to husbands or even to friends. There is something monstrous in the way she allows her infirmity to control the family, and something mysterious about the way they allow her to thwart their lives. Any show of independence or interest or engagement with the outside world on the part of the daughters results in Mother taking to her bed with debilitating and dramatic hysterics. So the girls are haphazardly and eccentrically educated at home and made to cook and clean and basically devote their lives to maintaining the domestic status quo.

But when the oldest daughter, Pandora, meets a nice young man while teaching Sunday School and manages to quickly get herself married to him and removed to London, the mother's iron grip is weakened, and the remaining daughters begin to rebel, and seek out men for their own. The novel centers around their collective pursuit of two candidates and the disastrous effect this has on the family's and the mother's stability.

But when the oldest daughter, Pandora, meets a nice young man while teaching Sunday School and manages to quickly get herself married to him and removed to London, the mother's iron grip is weakened, and the remaining daughters begin to rebel, and seek out men for their own. The novel centers around their collective pursuit of two candidates and the disastrous effect this has on the family's and the mother's stability.

The novel is narrated by the middle sister, Morgan, and she does a good job revealing her family and their queer world to the reader, which often reminds us of two other famous British literary families: the Bennetts and the Mitfords. But beneath the idiosyncratic comic veneer lurks disturbing and dark shadows concerning Mrs Harvey's health -- unlike the Bennett or Mitford parents, her eccentricity is not benign, and the book shades darker as it concludes.

Tutton is a deft and vivid writer, and knows how to keep her work breezy but also textured and somewhat complex. Her other two novels deal with incest and a woman's affair with her son-in-law, and I'd be interested in reading both of them, as I feel that she tackles difficult issues with a funny, rosy (yet thorny) touch.

The Nature of Passion by R. (Ruth) Prawer Jhabvala

(Nor...

The Nature of Passion by R. (Ruth) Prawer Jhabvala

(Norton, 1957)

The Nature of Passion, Jhabvala's second novel, is a thoroughly charming and very adroitly observed and written. I bought it because I had read somewhere that it was reminiscent of Jane Austen, and it is, although it takes place in a very different place (India) and time (mid-twentieth-century).

The Nature of Passion, Jhabvala's second novel, is a thoroughly charming and very adroitly observed and written. I bought it because I had read somewhere that it was reminiscent of Jane Austen, and it is, although it takes place in a very different place (India) and time (mid-twentieth-century).

Lalaji runs a successful construction business in Delhi, and lives somewhat luxuriously with his (unnamed) wife, his tyrannical and tradition-bound widowed sister, his six children -- 3 males and 3 females -- and assorted servants. His children are all pretty much settled, happily or unhappily married, except for his youngest son and daughter, who both want something different than their older siblings. Nimi, Lalji's beautiful and vivacious daughter, wants to get a college education and marry for love; Vidi, his son, wants to travel to Europe and then pursue a career in the arts. All of these desires run contrary to the family's and their culture's strong tradition, which require arranged marriages and for sons to follow their fathers into business.

The book has a large cast of very well-observed and entertaining characters and Jhabvala has an energetic and merry narrative sense. Her writing is first-rate -- clear and sensual. A lovely and delightful book.

November 22, 2019

Conventional Weapons by Joycelyn Brooke

(Bello, 2017; or...

Conventional Weapons by Joycelyn Brooke

(Bello, 2017; originally published by Faber & Faber in 1961)

This is a sad, failed book, a result of the author's timidity and short-sightedness and the time at which it was written. Like The Scapegoat, another Brooke book I've written about, this is a perfect example of how societal- and self-censorship thwarted so many pre-Stonewall gay writers.

This is a sad, failed book, a result of the author's timidity and short-sightedness and the time at which it was written. Like The Scapegoat, another Brooke book I've written about, this is a perfect example of how societal- and self-censorship thwarted so many pre-Stonewall gay writers.

First published in 1961, Conventional Weapons is the story of two brothers, Nigel and Geoffrey Greene, sons of a wealthy but common family and distant cousins of the (unnamed) narrator. His family is less wealthy but more refined, and they look down upon the Greenes: "no amount of education or upper-class conditioning seemed able to affect that racial strain of coarseness betraying itself in the thickened, almost porcine texture of the skin, in the bone structure of their faces, even from the way the hair sprouted from their heads. For as long as I can remember I had heard the Greenes referred to as common." Ugly stuff.

The two brothers are very different: Geoffrey, the eldest, is strong and masculine and pugilistic, and Nigel is effeminate and unsuccessfully arty (he fails as both a composer and artist before finding modest posthumous success as a novelist, writing a book much like the one we are reading). Geoffrey marries a dull girl names Madge, goes into business, has children, and become an alcoholic while Nigel pursues his failed artistic life in the seedy underworld of gay London. The narrator, maddeningly unforthcoming and coy about his own sexuality--he avoids using gendered pronouns when referring to his own lovers--moves back and forth between the the two disparate worlds of the brothers, apparently perfectly comfortable in each.

The two brothers are very different: Geoffrey, the eldest, is strong and masculine and pugilistic, and Nigel is effeminate and unsuccessfully arty (he fails as both a composer and artist before finding modest posthumous success as a novelist, writing a book much like the one we are reading). Geoffrey marries a dull girl names Madge, goes into business, has children, and become an alcoholic while Nigel pursues his failed artistic life in the seedy underworld of gay London. The narrator, maddeningly unforthcoming and coy about his own sexuality--he avoids using gendered pronouns when referring to his own lovers--moves back and forth between the the two disparate worlds of the brothers, apparently perfectly comfortable in each.

The novel is framed by a highly coincidental encounter of the narrator and Geoffrey late in their lives. Geoffrey has divorced poor Madge and married Frankie, Nigel's ex-wife (!), an unconventional well-bred woman (her father is a Lord) who specializes in marrying and "rescuing" alcoholics and closeted gay men.

In tone and subject matter, this books is very similar to Compton Makenzie's Thin Ice, which also observes homosexual life through the eyes of a supposedly straight man. Both narrators unintentionally, I believe, reveal themselves as being unbearable people: pompous, snobbish, judgmental, mean-spirited, and totally unsympathetic. It is sad to see how gay men attempted to write about (their own) queer lives in England when it was a crime to be homosexual. In order to get their books published, they must tell their stories through a poisoning scrim of self-denial and self-hate.

Parisian Lives by Samuel M. Steward

(St. Martin's Press,...

Parisian Lives by Samuel M. Steward

(St. Martin's Press, 1984)

Samuel Steward's dual lives as a tattoo artist/pornographer and man of letters are artfully combined in this breezy and engaging novel about the life of the mind and the life of the body.

Our narrator, Mac, is a young American academic (he teaches at a university in Chicago) who every couple of years has a fellowship to spend a season in Paris. He loves Paris, partly because his dear friends, Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas live there, and partly because it is abundantly verdant cruising ground for men, sailors, and boys.

Our narrator, Mac, is a young American academic (he teaches at a university in Chicago) who every couple of years has a fellowship to spend a season in Paris. He loves Paris, partly because his dear friends, Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas live there, and partly because it is abundantly verdant cruising ground for men, sailors, and boys.

While visiting Gertrude and Alice one summer at their rented home in the south of France, Mac meets Arthur Lyly, a young homosexual English aristocrat who is swanning through Europe with Wally, his hunky and dim-witted but devious American companion. Mac then relates the story of Arthur and Wally's relationship (it ends miserably) and then goes on to tell us about Arthur's next two relationships, one with a tough French boy who is a sadist, and the other with a beautiful gypsy boy newly arrived in Paris. They both also end miserably.

While most of the books is dedicated to the chronicling of Arthur Lyly's romantic life, perhaps a fourth of the book--or maybe less; a sixth--focusses on Mac's relationship with Gertrude and Alice. These scenes are lovely and satisfying. Steward was close to both women, and his love for and admiration of them is beautifully evoked. They both seem very real and alive in these pages, and encountering them through Steward's loving lense is delightful and illuminating.

While most of the books is dedicated to the chronicling of Arthur Lyly's romantic life, perhaps a fourth of the book--or maybe less; a sixth--focusses on Mac's relationship with Gertrude and Alice. These scenes are lovely and satisfying. Steward was close to both women, and his love for and admiration of them is beautifully evoked. They both seem very real and alive in these pages, and encountering them through Steward's loving lense is delightful and illuminating.

The rest of the book is less successful and interesting, but Steward is an accomplished writer: his 1930s Paris is vividly evoked, and he excels at creating moments that are alive both physically and psychologically. Unfortunately the book has a cheap and nasty plot twist and an ugly ending, so it's not the plot that distinguishes this book--it's Steward's winning evocation of a particularly lovely time and place.

The Two-Character Play by Tennessee Williams

(New Direct...

The Two-Character Play by Tennessee Williams

(New Directions, 1979)

I bought and read this copy of Tennessee Williams' oft-revised and retitled play many years ago, and I remember that I found it beautiful and intriguing. I feel the same after re-reading it now.

The Two-Character Play is in many ways a very pure and piercing distillation of Williams' theater. Its structure is simple, yet ingenious: the play takes place before and after a performance of The Two-Character Play, which was written by Felice and performed by him and his sister Clare. In it, they play themselves: two adult children whose father murders their mother and then shoots himself. They are left behind in the now haunted house, too damaged and frightened to leave it. The situation in which the give their final performance of the play is equally pathetic: they have been abandoned by the company while on a long and financially disastrous tour, and must perform the play in a cold dark theater before a disappearing audience.

The Two-Character Play is in many ways a very pure and piercing distillation of Williams' theater. Its structure is simple, yet ingenious: the play takes place before and after a performance of The Two-Character Play, which was written by Felice and performed by him and his sister Clare. In it, they play themselves: two adult children whose father murders their mother and then shoots himself. They are left behind in the now haunted house, too damaged and frightened to leave it. The situation in which the give their final performance of the play is equally pathetic: they have been abandoned by the company while on a long and financially disastrous tour, and must perform the play in a cold dark theater before a disappearing audience.

Felice and Clare are both terribly damaged yet resilient, and they know that if the tour fails, as it obviously has, their only alternatives are the State Mental Institution or death. So there is a lot at stake and they fight valiantly and poignantly with and against each other to transcend themselves by finding an ending to the play, which they sink back into when all else is lost.

This play has never been successfully produced. It may be unplayable, with the pathos and drama curdling into bathos and melodrama when enacted, but I think that with two very fine actors and a brilliant director (and designer--the stage world is complicated) it could be heartbreaking and beautiful, for at its essence is an almost unbearable flickering flame of Williams' sad and broken genius.

Michele Williams as Claire and Dennis Coard as Felice in a 2014 production of The Two-Character Play directed by Catherine Hill at the Winterfall Theater in Melbourne, Australia

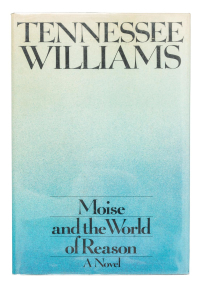

Moise and the World of Reason by Tennessee Williams

(Sim...

Moise and the World of Reason by Tennessee Williams

(Simon and Schuster, 1975)

This odd novel was written toward the end of Williams' life (he died in 1983) when he was struggling with drugs and alcohol and trying to regain his literary prowess and stature. Like Albee, he was thought to have lost his talent and genius and anything he produced was ridiculed and dismissed (unlike Albee, he did not live long enough to resuscitate his career and artist reputation). He did produce inferior work during this period, but much of it, like this book and The Two Character Play (1973; see above) contains passages that are heartbreakingly brilliant and beautiful.

Moise and the World of Reason (which is a terrible title--odd for TW, who was so usually so good with titles, especially early on--and does the book a real disservice) is narrated by a 30-year-old man living in a partitioned room in a huge unheated warehouse on the Hudson River at 11th Street. He is an unsuccessful writer who keeps his piles of rejection letters in the crate that he uses as his desk. His first lover, a Black figure skater, has died and he now lives with a younger lover, but they both seem to be biding their time.

Moise and the World of Reason (which is a terrible title--odd for TW, who was so usually so good with titles, especially early on--and does the book a real disservice) is narrated by a 30-year-old man living in a partitioned room in a huge unheated warehouse on the Hudson River at 11th Street. He is an unsuccessful writer who keeps his piles of rejection letters in the crate that he uses as his desk. His first lover, a Black figure skater, has died and he now lives with a younger lover, but they both seem to be biding their time.

The novel takes place over a single day and night. The narrator and his young lover attend a party at their friend Moise's one-room apartment on Bleecker Street. Moise is an enigmatic and waifish painter who specializes in paintings that appear to be unfinished. At the party she announces that she is withdrawing from "the world of reason" and the narrator's lover runs off with another man for dinner at Phebe's (which still exists, having miraculously survived the gentrification of the East Village). The narrator returns to the warehouse and spends the entire night writing in his Blue Jay notebooks, and when he has filled his last one, he resorts to writing on the backs of his rejection letters and on shirt cardboards (which is something James Ivory also does). He writes about growing up queer in Selma, Alabama and running away to the New York City when he was 15, meeting the figure skater, who referred to himself as "the nigger on ice," and their symbiotic friendship with Moise. A few visitors interrupt his writing marathon, and the book concludes with him returning to Moise's room where they seem to be fated to live together in an unworldly darkness and silence (the one window in her room has frosted glass).

Parts of this book are funny, engaging, and written with Williams' poetic flair. His recollections of his mother and grandmother and his figure skater lover are particularly vibrant and fun to read. He writes frankly and graphically about sex and human bodies--it's as is if he making up for all the suppression and inversion in his great plays, and some of the language and acts described are shocking, and must have been extremely offensive to readers in 1975. The New York Times review of this book is a snide, mean, homophobic dismissal, and reading it one feels the derision piled upon Tennessee Williams during this late period. It's sad.

Another interesting thing about this book is its accurate and highly detailed evocation of New York City c. 1975. Williams uses real names of places (Phebe's, The Factory) and people (Warhol, Mary McCarthy, Jane Bowles) and this gives the book a gritty specificity I recognized in the city as I first encountered it in the late 70s and early 80s.

Note: the image above is the cover a New Directions edition of the book, reissued in 2016. I read the original Simon and Schuster edition, pictured below.

November 20, 2019

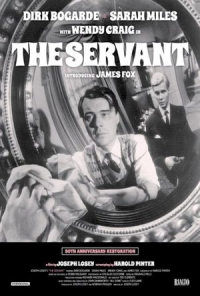

The Servant by Robin Maugham

(Harcourt Brace & Co., 1949...

The Servant by Robin Maugham

(Harcourt Brace & Co., 1949)

An unpleasant and undernourished novella, The Servant might have seemed daring and original in its day, but has not withstood the test of time.

An unpleasant and undernourished novella, The Servant might have seemed daring and original in its day, but has not withstood the test of time.

It's the story of two recently de-mobbed bachelors in London, both of whom seem to be gay and probable lovers, but of course they're not. It helps that the girl (she's 16) at the center of this menage is a certified frothing-at-the-mouth nymphomaniac. The titular character, Barrett, is a man servant who completely eclipses and control's his master's house and life. In Harold Pinter's hands this might have seemed credible and chilling, but the young Maugham isn't astute or adroit enough to make any of this nonsense believable or even engaging.

I remember the film version of this book, starring Dirk Bogard, written by Pinter, and directed by Joseph Losey, as being a subtler and more interesting treatment of this material. I wonder how it withstands the test of time.

November 19, 2019

The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne by Brian Moore

(Atl...

The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne by Brian Moore

(Atlantic, Little Brown, 1965)

The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne (originally titled Judith Hearne), like so many books that have a relentlessly downward-spiraling plot, hooks the readers and carries them forward with ever-growing narrative force. Once caught in its vortex, it is hard to put the book down, so compelling is the plight of its heroine.

Judith Hearne is a 40ish unmarried woman living in Belfast sometime in the 1950s. Her life seems to have run itself out far too quickly, leaving her poor, "plain," lonely, frightened, and alcoholic. The book begins as she moves into yet another in a long series of depressing rooms in rooming houses in what seems to be perpetually raining Belfast. But this new attempt to begin again goes wrong right from the start when she meets her landlady's brother, recently returned from New York City under dubious circumstances. Miss Hearne, due to her ever-mounting sense of anxiety and delusion, convinces herself that this man is a wealthy suitor--her last chance for marriage and happiness. In fact he is only interested in her as potential investor in his pipe-dream business plan to open an American-type hamburger joint in Dublin, and so the two court each other to tragic consequence.

Surrounding and interwoven with this central (non)romantic plot are flashbacks of Miss Hearne's difficult past. She was orphaned at an early age and raised by a proud and snobbish aunt who instilled in her a sense of superiority and entitlement that only set her up for constant humiliation and disappointment. The book also explores her complicated and mostly pathetic "friendship" with the O'Neil family, all of whom bear her weekly visits with badly disguised contempt and cruelty.

Surrounding and interwoven with this central (non)romantic plot are flashbacks of Miss Hearne's difficult past. She was orphaned at an early age and raised by a proud and snobbish aunt who instilled in her a sense of superiority and entitlement that only set her up for constant humiliation and disappointment. The book also explores her complicated and mostly pathetic "friendship" with the O'Neil family, all of whom bear her weekly visits with badly disguised contempt and cruelty.

Judy Hearne is a tragic and pathetic character, yet Brian Moore allows us to glimpse, through her unawareness and alcoholic destructiveness, a woman who is trying as hard as she can to lead a decent and dignified life. I found this book to be a tad mean spirited--about all the characters, not just the title character. Moira O'Neil is the only character who behaves with kindness and common decency. One feels the world and the circumstances that Judith Hearne faces are perhaps almost sadistically punishing.

Peter Cameron's Blog

- Peter Cameron's profile

- 589 followers