Peter Cameron's Blog, page 15

August 16, 2018

Guest of a Sinner by James Wilcox

(Harper Perennial, 1995)

I had read and enjoyed several James Wilcox novels (Modern Baptists, Miss Undine's Living Room, Sort of Rich) back in the 1980s when they were first published, but hadn't read anything of his in a long time, so when I saw a paperback copy of this book for sale in the used books section of Northshire Bookstore in Manchester (Vermont), I bought it, and I'm glad I did.

Unlike earlier Wilcox novels, which take place in the South and have an evident southern sensibility, Guest of a Sinner is set in New York City, and is saturated with details of life in NYC late in the 20th century. Wilcox is very good at capturing the moods and atmospheres of the city, and the book is generously populated with a large cast of authentic and eccentric fin de si��cle New Yorkers.

At the center of all these characters is Eric Thorsen, a man whose stupefying beauty has in some ways incapacitated him. A talented but unsuccessful pianist, Eric (barely) makes his living as a rehearsal pianist and teaching piano to underprivileged students, while dreaming of his fabulous debut at Carnegie Hall. He lives in an (illegally acquired) rent-controlled apartment in Murray Hill. His sister, Kay, lives in a gloomy basement apartment on the Upper West Side. (Like all good NYC novels, this one revolves around real estate, and a sort of residential musical chairs drives much of the farcical plot.) Kay works in Macy's Cellar and is having a doomed but happy affair with a married man; Eric panicked and left his fiance at the altar many years ago and subsequently leads a monastic existence in New York (he is often mistaken for a homosexual).

At the center of all these characters is Eric Thorsen, a man whose stupefying beauty has in some ways incapacitated him. A talented but unsuccessful pianist, Eric (barely) makes his living as a rehearsal pianist and teaching piano to underprivileged students, while dreaming of his fabulous debut at Carnegie Hall. He lives in an (illegally acquired) rent-controlled apartment in Murray Hill. His sister, Kay, lives in a gloomy basement apartment on the Upper West Side. (Like all good NYC novels, this one revolves around real estate, and a sort of residential musical chairs drives much of the farcical plot.) Kay works in Macy's Cellar and is having a doomed but happy affair with a married man; Eric panicked and left his fiance at the altar many years ago and subsequently leads a monastic existence in New York (he is often mistaken for a homosexual).

Both Kay and Eric become involved with a hapless and rather bedraggled woman named Wanda Shopinski, who is having apartment problems of her own. Orbiting around this central triad is a constellation of very bright minor characters: Mrs. Una Merton, who lives directly below Eric with her dozens of stray (and highly odoriferous) cats; Mrs. Fogarty, the owner of a newstand who does not hesitate to participate and manipulate other people's lives; Lamar Thorson, Kay and Eric's tragically (and mysteriously) widowed father, who lives in Tallahassee but appears with alarming frequency in New York; Russell Monteith, Eric's very wealthy friend who has recently divorced his wife and embraced a homosexual lifestyle, and Arnold Murtaugh, a short ex-priest with a mysterious sexual charisma.

Wilcox makes a delicious and quietly hilarious souffle from these ingredients. His humor is so subtle and unforced that the reader often wonders if Wilcox himself is on the joke. Wilcox makes most other comic novels seem gross and artificial by comparison -- perhaps because his humor is always connected to the underlying pathos of his characters' humanity. They strive to be (and do) good in a world that seems especially designed to embarrass and defeat them.

August 15, 2018

Mates by Tom Wakefield

(Gay Men's Press, 1983)

An interesting and engaging novel that chronicles the "marriage" of two gay men in England. Cyril and Len meet one another at a basic training camp while performing their National Service in 1954. They exchange "conspiratorial smiles" and quickly fall in love, and begin a relationship that lasts until Cyril's sudden death (of heart attack) in 1981.

An interesting and engaging novel that chronicles the "marriage" of two gay men in England. Cyril and Len meet one another at a basic training camp while performing their National Service in 1954. They exchange "conspiratorial smiles" and quickly fall in love, and begin a relationship that lasts until Cyril's sudden death (of heart attack) in 1981.

The novel is artfully composed of eleven chapters that read like stories; each chapter jumps forward in time from two to five years. This episodic yet detailed and intimate portrait allows the men and their relationship to realistically and interestingly evolve over time. They split up at one point and pursue other loves, but reunite a short while later, both realizing that they are happier together than apart.

Cyril and Len suffer the indignities, inconveniences, and persecution of being gay in postwar England, but nevertheless manage to lead a conventional and happy domestic life together. Neither of the men is particularly interesting and the book is mostly focused on the drudgery of everyday life, but this lack of sensation gives the men a genuine humanity, and their relationship, which is considered so abnormal and a such a threat to polite society, is as ordinary and natural as their love.

The American Stranger by David Plante

(Delphinium, 2018)

I found this book at Rizzoli's when I went there to buy a copy Sigrid Nunez's The Friend for a friend. I had no idea that David Plante, a writer I have long admired, was publishing a new novel and was delighted to find and buy the book (fortunately P is close to N) . I started reading it almost immediately and was captivated by its piercing beauty and wisdom. I think it is an extraordinary book.

The American Stranger follows the young adult life of Nancy Green, a Jewish girl from New York City getting her masters degree in literature (Henry James, of course) in Boston. Nancy's parents are refugees from Germany and are secretive about their past. They are wealthy and cultured and Nancy is well loved by both her parents.

In Boston, she meets Yvon, an odd and insular young man who grew up in a "parish" of French Canadians in Providence, Rhode Island. He is younger than Nancy, an undergraduate. The first half of the book chronicles Nancy and Yvon's passionate love affair, which ends traumatically for both of them when Yvon's unstable and dependent mother kills herself, feeling abandoned by her son.

In Boston, she meets Yvon, an odd and insular young man who grew up in a "parish" of French Canadians in Providence, Rhode Island. He is younger than Nancy, an undergraduate. The first half of the book chronicles Nancy and Yvon's passionate love affair, which ends traumatically for both of them when Yvon's unstable and dependent mother kills herself, feeling abandoned by her son.

Nancy then meets and somewhat rashly marries Tim, a wealthy refined British Jew from the Middle East, who works as a barrister in London. Their marriage is a disaster almost from the beginning. Tim is cold and abusive, Nancy feels alone in unfriendly London, and suffers several punishing miscarriages. (One of the reasons Tim married her was because he wanted children -- his first wife was unable to.) When Nancy finds out that Tim's mistress is pregnant with his child and that he plans to keep both the woman and the child in his life, she leaves him and returns to New York. The book ends with her failed attempt to find Yvon, who has disappeared.

Plante's writing is faultless: poised and elegant, and both the world and characters in the book have a haunting and slightly mysterious aura. The American Stranger is a jewel.

The Summer Before the Dark by Doris Lessing

(Knopf, 1973)

A disappointing and somewhat tedious novel from Lessing. Perhaps it's because the main character, the dully named Kate Brown, is an unengaging and unlikable woman. After devoting herself selflessly and tirelessly to raising her four children, coddling her selfish husband, and maintaining a charming household in suburban London, Kate finds herself at 40 with a purposeless and passionless life. Fortunately, sh e is fluent in Portuguese, so when her husband and children all leave her for the summer to pursue opportunities in far-flung places abroad, she is hired at an international human rights agency, where she finds that her experience as a mother and housewife qualify her to serve as a sort of corporate den mother, solving everyone's problems and tidying up other people's messes.

e is fluent in Portuguese, so when her husband and children all leave her for the summer to pursue opportunities in far-flung places abroad, she is hired at an international human rights agency, where she finds that her experience as a mother and housewife qualify her to serve as a sort of corporate den mother, solving everyone's problems and tidying up other people's messes.

After a few months working in London as a nanny/interpreter, she is sent to manage a conference in Istanbul. There she meets a much younger man; they become lovers and when the conference concludes they take a holiday together to Spain where they both become gravely ill. This is the only part of the book that is narratively engaging: Kate and her young lover unwisely travel to a remote Spanish village where no medical care is available, and Lessing potently evokes nightmarish Sheltering Sky atmosphere of being dangerously out of one's depths in a foreign land.

Kate abandons her nearly dead lover, who is being diligently but inexpertly nursed by nuns at a nearby convent, and gets herself back to London, where she recuperates in a luxurious hotel for several (very expensive) weeks. She recovers her health but finds herself financially compromised, and so moves into a basement flat owned by a strange kittenish young woman, with whom she forms a strong but unbelievable bond. They live together for several tedious months of mutual healing and self-discovery and then Kate Brown abruptly decides to return to her family and her home.

This book is very much a product of its time. The fact that it attempts to explore the difficulties of a woman searching for a rewarding and fulfilling life as something other than a mother or wife is worthy and admirable, but Kate's insufficiently imagined and evoked life prevent Lessing's novel from engaging or rewarding the reader.

April 26, 2018

A Heavy Feather by A. L. Barker

(The Hogarth Press, 1978)

Another dark, disturbing and idiosyncratically brilliant book by this fascinating writer. A Heavy Feather is self-defined on the half-title page thusly: This is the story of Almayer Jenkin's progress through life. "You start alone, you finish alone, " she says. "It's fine to be alone, it's a revelation, truth at last."

The book does, indeed, as promised, follow Almayer Jenkin through her life, beginning when she is a young child and finishing in her old age. Yet it does this in an unusual and interesting way: the novel is comprised of nine chapters, and each of them records a brief period in Almayer's life from different vantage points alternating between first and third person. In the sections narrated by Almayer (about half) she is very much at the center of the book, but in many of the other sections, different characters -- her fathe r, her friends, her husband, her son -- take center stage and Almayer's presence in the book is refracted and tangential.

r, her friends, her husband, her son -- take center stage and Almayer's presence in the book is refracted and tangential.

Almayer is an interesting and original character from any and all angles. Her mother left her and her father when she was a baby, and her father, a loving but dangerously incompetent parent, barely supports the two of them with his struggling plumbing business. He dies when Almayer is a teenager, and she is sent to live with a family of benevolent strangers whose life she fairly ruins with her naivete and instinctual honesty. She then sets out on an independent life, first becoming involved with a pair of mismatched homosexual lovers (as usual, Baker's world matter-of-factly includes characters of many different and under-represented sexual persuasions) and later marries a kind and decent (but somewhat clueless) husband. She ends her life as a successful yet solitary business owner in London.

As with all books by Barker, what makes this one especially interesting is the acuity of the author's perception and expression. The book skips haphazardly (it seems) through time and space but each time it lands Baker's skills allow her to quickly evoke a complete and authentic world inhabited by interesting and well-developed characters. And so, despite its fractured and episodic nature, the novel feels rich and whole, and Baker's prose is as bracing, funny, and elegantly assured as always.

Patricia Brent, Spinster by Herbert Jenkins

(George H. Doran, 1918)

A slight and silly but charming book set in London during WWI. Patricia Brent, an intelligent and resourceful young lady, is resigned to her fate as a spinster although she is still in her twenties. She lives as a "paying guest" in a rooming house along with many other sad and thwarted people, and works as a private secretary for a "rising" young member of Parliament (it is doubtful he will ever rise).

A slight and silly but charming book set in London during WWI. Patricia Brent, an intelligent and resourceful young lady, is resigned to her fate as a spinster although she is still in her twenties. She lives as a "paying guest" in a rooming house along with many other sad and thwarted people, and works as a private secretary for a "rising" young member of Parliament (it is doubtful he will ever rise).

One day she recklessly tells her housemates that she is engaged to be married, and thus begins the romantic adventure that leads her to the altar. She presses a strange man in a restaurant into posing as her fiance, and it turns out he is no other than Lord Peter Bowen, one of London's most desirable and charming bachelors. He immediately falls in love with the Patricia and insists that their pretend engagement is real. This annoys Patricia and she spends most of the book trying to withstand his (charming) courtship, despite all the help he is given by his (charming) friends and (charming) family.

The book is amusing -- many of the characters are urbanely funny, including Patricia, who has a wry and cynical sense of humor. But because Peter is so thoroughly charming, Patricia's obstinancy seems contrived to provide a plot, and this makes the book seem somewhat effortful -- it lacks the scintillating elegance and speed of Evelyn Waugh's early novels (Vile Bodies, Decline and Fall).

The Friend by Sigrid Nunez

(Riverhead, 2018)

Sigrid had told me a year or so ago that she was working on a novel about a woman who inherits a Great Dane after the dog's owner, a friend of the woman's, dies. This sounded like a promising premise for a novel, so I felt predisposed to like the book, but I was surprised by how much Sigrid does with this simple premise and how rich and rewarding this book is.

The narrator is an independent woman who lives alone, a writer, an intellectual, a professor. The friend whose dog she inherits is also a writer and teacher -- in fact he was the narrator's teacher and mentor early in his career, but the narrator, unlike many of her fellow female students, did not have an affair or marriage with the man. Instead they shared a long and close friendship.

She is surprised, however, when he commits suicide, perhaps because of writer's block, and his third wife tells her it was his wish that she would adopt his dog, Apollo, a Great Dane that he had found abandoned in Central Park. Although the narrator has no experience of owning dogs (she is a self-avowed cat person) and lives in a rent-controlled apartment that forbids them, she agrees to take the dog, and of course bonds with it in a very real and touching way.

The story of the narrator's and Apollo's courtship and romance is constantly interrupted by observations and explorations of many diverse topics (dogs in literature, the relation between men and women and sexual harassment, competition in the literary world, life in New York City). By including so much material that is not fictionalized and reads like essays, Sigrid gives this novel a very original and pleasing texture. At times the writing and tone made me think of several other writers: Susan Sontag (interesting, given Sigrid's relationship with her -- see Sempre Susan), David Markson, Lily Tuck, Lydia Davis. There is something very cool and bracing about the tone of the book that completely prevents the dog story from becoming sentimental: it's a very winning combination of subjects and tones, and makes the book seem very fresh and refreshing.

It felt to me as if in some way Sigrid had found her true voice in this book -- or perhaps it is only the matter of her doing in this book what she is so adept and skilled at doing, and not trying to do anything that is usually expected from a novel. A smart and beautiful book.

January 31, 2018

The Handyman by Penelope Mortimer

Joan Kahn/St. Martin's Press, 1983)

I've read and enjoyed many books by Penelope Mortimer (The Pumpkin Eater, My Friends Say It's Bulletproof, The Home, A Villa in Summer, Daddy's Gone A-Hunting, Saturday Lunch at the Browning's), and I think I liked this one least of all. In fact, I found The Handyman to be a almost thoroughly unpleasant book.

It's the story of an older woman learning how to live on her own without children or a husband -- a situation that is also explored, with far more subtlety and acumen, in Mortimer's book The Home.

Phyllis Muspratt's husband drops dead one morning at the breakfast table, and she is forced to maintain her genteel and comfortable life with little help from her son and daughter (she appears to have no friends). She sells the family house in Surrey and moves to a somewhat dilapidated country cottage in the drab and ornery village of Cryck, which is ruled over by a despotic landowner called The Brigadier and whose citizens are terrorized by The Brigadier's "boys," an unsavory pack of young men who ride around on motorcycles damaging personal property.

Phyllis Muspratt's husband drops dead one morning at the breakfast table, and she is forced to maintain her genteel and comfortable life with little help from her son and daughter (she appears to have no friends). She sells the family house in Surrey and moves to a somewhat dilapidated country cottage in the drab and ornery village of Cryck, which is ruled over by a despotic landowner called The Brigadier and whose citizens are terrorized by The Brigadier's "boys," an unsavory pack of young men who ride around on motorcycles damaging personal property.

Also living in Cryck is Rebecca Bourne, an Iris Murdoch-ish author, who has lost the inspiration to write and who maniacally gardens, smokes cigarettes, scowls, and is thoroughly unpleasant to everyone she comes in contact with. Phyllis tries to befriend Rebecca with no luck at all, but does endear herself to Rebecca's damaged daughter, who has just been released from the bin (her word) after a suicide attempt.

Phyllis's two children are both preoccupied with their own lives. Her (gay) son Michael is an editor at the London publishing house that -- surprise! -- once published Rebecca Broune, and her daughter, Sophie, is a wife and mother who doesn't really seem to like her mother or care very much about her, perhaps because she has her own problems -- her husband Bron is a serial philanderer.

When life in Cryck becomes unbearable -- the titular handyman of the title, who is renovating Phyllis's cottage, turns out to be a total sexual creep and tries to molest her -- Phyllis decides to sell the cottage and move to a retirement home, where she can live safely and happily with other genteel, tea-drinking people and enjoy her old age in peace and quiet. She arranges all this behind her children's back and days before she is due to make the move, while feeling the happiest she has ever felt in her entire life, she falls down the attic stairs, hits her head on the door, and instantly dies. (It takes four days for her body to be found.)

Putting a nice, if boring, character like Phyllis through such dreary ordeals only to have her die accidentally at the end of the book seems rather cruel and perverse to me -- to both the character and the reader. Perhaps Mortimer feels that Phyllis is too dull and conventional a character to exist, but why write about her in that case?

The one interesting thing about this dreary book is the inclusion, as in all Mortimer's books, of the authentic sexual lives of the characters. Phyllis, genteel as she is, is a sexual being, which the handyman senses and acts upon (although he's a creepy and incompetent seducer, parading before her with his "private parts" bulging "through the thin cotton" of "his patterned underpants."). But Penelope Mortimer is no kinder to Phyllis than the handyman, and so this book is mean and sour.

The Flight of the Pelican by John Hopkins

Chatto & Windus/Hogarth Press, 1983

I had very much admired two other books by John Hopkins, which I had read many years ago: Tangier Buzzless Flies and The Tanger Diaries 1962 - 1979, a non-fictional and fictional account of the time Hopkins spent in Moroccoo in the '60s and '70s. These books are both artful and intelligent, and written with considerable artistry and skill.

I had very much admired two other books by John Hopkins, which I had read many years ago: Tangier Buzzless Flies and The Tanger Diaries 1962 - 1979, a non-fictional and fictional account of the time Hopkins spent in Moroccoo in the '60s and '70s. These books are both artful and intelligent, and written with considerable artistry and skill.

Unfortunately I did not think The Flight of the Pelican was anywhere near as good as those two books. It's an overwrought adventure novel, set in an imagined South (or Central) American country, where everything and everyone is larger than life and simultaneously comic and lurid.

Jonathan Bradshaw, the good-for-nothing scion of a wealthy and well-connected New England family, journeys to Puerto Gosano in search of his father, who sailed south 25 years ago, disappeared, and is assumed to be dead. But when his sailboat, the Pelican, is found the family believes he might still be alive in the jungles of Puerto Gosano, and dispatch Jonathan forthwith.

Jonathan creates a lot of (unbelievable) mayhem and encounters a lot of terrible things ( vampire bats, a house full of genetically-deformed orphans, feral dogs, vultures), before finding his father, who is indeed living in the jungle with his ferocious knife-wielding common-law wife, and suffering from a terrible rotting skin disease brought on by unsanitary jungle life.

The first two-thirds of the book are somewhat engaging, but when Jonathan finally encounters his father, most of the buoyancy and energy dissipate and the final third of the book (like the tail-end of so many journeys) is tedious and exhausting. Hopkins writes alluringly about geography and flora and fauna, and this gives the book a consistent sensual vividness, but it is not enough to sustain a reader's interest, for the world of the book, though well evoked, is finally too unreal and arbitrary to engage a reader's attention or sympathy.

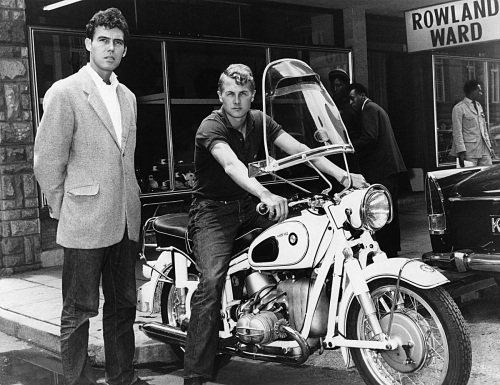

John Hopkins (l) and Joe McPhillips (r)

John Hopkins (l) and Joe McPhillips (r)

A Source of Embarrassment by A. L. Barker

Hogarth Press, 1974

Another fascinating book by this interesting and idiosyncratic writer; I think that I liked this best of the three I have read. There is something antiseptically bracing about A Source of Embarrassment that makes reading it both disturbing and delightful.

The source of embarrassment is a middle-aged Englishwoman, Edith Trembath, who lives with her husband and two children in some provincial city or town in England. She is a difficult character to describe, partly because she is so unusual and partly because Baker doesn't strive to reveal her characters: she observes them dispassionately from a distance.

At the beginning of the book Edith is diagnosed with a brain tumor and told she has three months to live, and the book explores how both she and her family and friends respond to this tragic situation. Complicating matters is the fact that Edith is a pathetic figure of fun to everyone she knows. They all mistake her clumsiness and her inability to detect sarcasm or irony or scorn as proof that she is some sort of imbecile -- even her children and husband, though fond of her, patronize and marginalize her. It is only the reader, who observes her at a slightly different angle, who can discern her integrity and true worth.

This book is also inclusive of its characters' varied sexual lives. Attention is paid to everyone of them, and there is frank and candid mention of incest, impotence, and adultery. In this way, the book seems very adult and ahead of its time.

Barker's writing is, as always, funny and brilliant. Her tone is unique, although at moments this book made me think of both James Schuyler's What's For Dinner and any number of Iris Murdoch novels. I'd like to read this book again, for Barker's writing isn't always easy to comprehend or appreciate, and I feel that a second reading would reveal many additional delights and satisfactions.

Peter Cameron's Blog

- Peter Cameron's profile

- 589 followers