Dmitry Orlov's Blog, page 28

March 26, 2012

Trained for Success, Bred to be Eaten

I ended my lastpost with a provocative question:

I ended my lastpost with a provocative question:Why is thatreasonably rational individuals who are able to follow an argumentand who are unable to refute it are at the same time incapable ofmaking the transition from thought to action? What is stopping them?Humans are clearly smarter than yeast, what does that matter if theyare incapable of acting any more intelligently?

As I promised, I will attempt toaddress this question in this one, helped by all the comments I havereceived. Ugo Bardi was quick to contribute this:

People just don'tcare about understanding what's going on and what's going to happen.If they are rich they care about how to make money on oil; if theyare poor they care about miracle devices that will save us from thebrink of the cliff. Then, as we start falling, interest inunderstanding what's going to happen will fade even more.

Ugo also cited TooSmart for Our Own Good by Craig Dilworth, summarizing it asfollows:

The gist ofDilworth's book is that we are smart, individually, but that wearen't collectively. So, we are very good at solving individualproblems, but that has the cost of creating larger collectiveproblems which, then, we can't solve.

Dilworth's own summary of his bookcontains this:

We are destroyingour natural environment at a constantly increasing pace, and in sodoing undermining the preconditions of our own existence. Why is thisso? This book reveals that our ecologically disruptive behaviour isin fact rooted in our very nature as a species. Drawing on evolutiontheory, biology, anthropology, archaeology, economics, environmentalscience and history, this book explains the ecological predicament ofhumankind by placing it in the context of the first scientific theoryof our species' development, taking over where Darwin left off. Thetheory presented is applied in detail to the whole of ourseven-million-year history.

This provides me with as good a jumpingpoint as any, so let me begin.

Do you know of any humans that areliving sustainably, in complete balance with the natural world?Chances are, you don't, unless you are an anthropologist, and eventhen only if you are lucky. Such humans are by now quite thin on theground. Most of them have been either murdered or herded into"civilized" (i.e., unsustainable) society. Sustainable humans area difficult subject to study, because our history is the history ofunsustainable living, and ignores long, undocumented periods of timeduring which nothing notable took place in a multitude of sparselypopulated locations.

But had these nondescript humansbeen left alone, the result would have been largely the same. Yousee, groups that live sustainably, in balance with the naturalenvironment, do not experience exponential population growth. And sothe populations which did not exhibit the fatal traits that give riseto Dilworth's "predicament of mankind," even if left unmolested,would have quickly found their numbers dwarfed by the initially tinypart of humanity that increased its numbers exponentially byconsuming nonrenewable resources while degrading the naturalenvironment. As with a yeast sample, population size doesn't matter;all that matters is that you have a few viable specimens of the rightstrain, to start a culture.

A spike and crash in human populationsis not unprecedented: out of a population of humans living inhomeostatic equilibrium within their constant environmental footprinta small group emerges that, through some technologicaldevelopment—stone-tipped spears useful for big game hunting, or aplow design useful for breaking sod for agriculture, or toxicfracking fluid cocktails useful for getting at the dregs of fossilfuel resources—gains access to a new energy resource. Madedelirious by their newly-gained powers, they throw all caution to thewind. Their population soon starts to double, crowding out everyoneelse. In the process, they hunt the big game to extinction, turnprairie to desert and deplete reserves of fossil fuels. Once furtherinvestment of energy in exploiting their favorite resource begins toproduce diminishing returns, the population dies back, and a newhomeostatic equilibrium reemerges, at a lower population level thanbefore, because of the lowered carrying capacity of the now degradedenvironment. What makes the current experiment in unsustainablegrowth different is that it has engulfed the entire planet, depletingnot just some but all natural resources in tandem.

The human populations that can live inequilibrium with their environment for thousands of years, and thosethat destroy it in a hurry, are not different species; they are noteven different subspecies. Evolution has precious little to do withtheir differences: it is a matter of culture, not genetics. The timescale on which these events take place is far too short forlong-lived organisms like humans to evolve any traits as specificadaptations to them. There are a few adaptations that develop this quickly:darkening orlightening of skin in response to sunlight, which takes less than 10000 years; resistance to diseases, through attrition of individuals who lacked genetic resistance tospecific pathogens; changes in body form, lanky and hairless to shed heat in hot climates, portly and hairy to conserve it in cold ones. Beyond that,humans exhibit remarkably little genetic variation.

Although "culture" is an easy labelto apply, and although cultural differences do abound, whatdistinguishes a population that insists on looking seven generationsback and seven generations into the future when making decisions fromone that is mainly concerned about the quarterly revenue and theyear-on-year growth and their effect on stock price is theirdifferent thought processes (or lack thereof), which are, in turn,determined by their different priorities. You see, the man who livesand dies by the quarterly earnings report is already living right atthe brink of extinction, eating through nonrenewable resources fasterand faster, riding the exponential curve on the way up. As soon asthat ride stops, he might as well promptly drop dead, but he will usually want to give cannibalism a try first.Thinking about the remote future is just not an effective short-termsurvival strategy for him. Asking him to invest in a sustainabledevelopment strategy based on some medium to long-term projections islike asking a man who is being chased by other men armed with knivesand forks—and feels that he is in immediate danger of beingeaten—to stop and help you with a crossword puzzle.

And herein lies the conundrum: topreserve all that's worth preserving—which, to me, is all the culture thatis actually worth the name—art, literature, music, science,philosophy and fine craftsmanship—and to carry it over into asustainable, low-energy, low-impact way of life, requires access toresources, and that, in turn, takes substantial quantities of money. But moneyis controlled by people who are always busy running away from theircompetitors lest they be eaten, and who cannot see how investing in ascheme which will never "pay off" could possibly be to theirpersonal advantage or benefit (which is all the poor fools seem able to think about). How can we make it so that "the fool and hismoney are soon parted"? I have some ideas, and I will take up thisquestion up in the next post or two.

Published on March 26, 2012 09:48

March 9, 2012

C-Realm: Theater of the Mind

In this 300th C-Realm Podcast episode, KMO welcomes Dmitry Orlov back to the program to check in on the collapse narrative and to compare the actual unfolding of events with Dmitry's perspective of five years ago.

"...I did an episode a few months back with—Guy McPherson was on, and Kurt Cobb, and Henry Warwick. And Henry was saying that it's just really irresponsible to talk about collapse to audiences who don't understand the very specific meaning of the word you have in mind, because generally when people hear "collapse," they think 'Mad Max Scenario', when in fact a collapse in the Joseph Tainter sense can be advantageous, you know, in fact it could be that we are due for some financial, political and commercial collapse, but social and cultural collapse are things you would want to avoid at all costs."

"Well, yes, it's not all one thing. The criticism that I use this word, well, you know, let them propose a different word. I haven't exactly redefined what I'm talking about, I'm just adding detail. So I don't know if that's entirely valid."

Published on March 09, 2012 00:16

March 5, 2012

No Physical Basis for Recovery

Cyril Lagel[This is a guest post from Chris, who has been looking into nonrenewable resource depletion for some time now. His conclusion is that, even if oil weren't the immediate problem, we'd still be "running out of planet" for many commodities without which an industrial civilization will collapse.]

Cyril Lagel[This is a guest post from Chris, who has been looking into nonrenewable resource depletion for some time now. His conclusion is that, even if oil weren't the immediate problem, we'd still be "running out of planet" for many commodities without which an industrial civilization will collapse.]The prevailing perception among the American public is that the hard times we are currently experiencing are temporary, that their leaders are implementing the proper mix of economic and political fixes, and that life will be back to normal soon. While this perception is entirely understandable given their historical experience, it is also entirely wrong. There will be no recovery this time.

Nonrenewable natural resources (NNR) are industrialized humanity's fundamental enablers. The industrial lifestyle (the "American way of life," if you will) is made possible almost exclusively by enormous and ever-increasing quantities of finite and non-replenishing NNRs: fossil fuels, metals, and nonmetallic minerals.

NNRs are the raw material inputs to the industrialized economy, providing both the building blocks that make up industrial infrastructure and support systems and the primary energy sources that power industrialized society.

NNRs comprise approximately 95% of the raw material inputs to the US economy each year. In 2008, the US used up nearly 6.5 billion tons of newly mined NNRs, or 43,000 pounds per capita. This is an almost incomprehensible 162,000% increase since the year 1800.

America's historical experience has been one of having continuously more and more with each generation. Since the start of their industrial revolution in the early 1800s, but especially during the 20th century, America's level of societal well-being and material living standards have improved dramatically.

[image error]20th Century USSocietal Well-beingWhile US population increased by 270% between the years 1900 and 2000, from approximately 76 million to over 282 million, per capita US GDP, which is a proxy for the average material living standard, increased by 610%, from less than $6,000 annually to nearly $40,000 annually (source). This increase in American societal wellbeing was made possible by ever-increasing utilization of NNRs, which were both abundant and affordable.

[image error]20thCentury USNNR Utilization

Total annual US NNR utilization increased by an extraordinary 2100% between the years 1900 and 2000, from approximately 300,000,000 tons to over 6,700,000,000 tons; while annual per capita US NNR utilization increased by 525% during the same period, from approximately 7,700 pounds to over 48,100 pounds. (Source: Mineral Information Institute, from USGS data)

For the entire 20th century, Americans reality can be summarized as "continuously more and more." This being the common experience, it is little wonder that a cornucopian worldview had become firmly entrenched within the American mindset. Most Americans firmly believe that we can achieve perpetual economic growth, continuous population expansion, and ongoing improvement in material living standards through ever-increasing utilization of the earth's unlimited supplies of NNRs.

But, as their designation implies, NNR supplies are not unlimited. NNR reserves are not replenished on a time scale that is relevant to human history. Moreover, economically viable supplies associated with the vast majority of the NNRs that enable an industrialized way of life are becoming increasingly scarce, both domestically (in the US) and globally.

Domestic NNR scarcity increased throughout the second half of the 20th century and into the 21st, so that by the year 2008, immediately prior to the Great Recession, 68 of the 89 NNRs (76%) were scarce domestically. That is, domestically available, economically affordable NNR supplies were unable to meet US demand. NNRs that were scarce domestically included chromium, cobalt, copper, magnesium, natural gas, oil, potash, silicon, tin, titanium, uranium, and zinc. NNR imports provided fully 100% of 2008 US supplies in 19 of 89 cases (21%). NNRs for which the US was totally import-reliant included bauxite, graphite, fluorspar, indium, manganese, niobium, quartz crystal, rare earth minerals, tantalum, and vanadium. While the US has been able to rely increasingly on imported NNRs to offset ever-increasing domestic NNR scarcity, the world has no such safety net: there is only the one Earth, and it imports nothing.

By the year 2008, 63 of the 89 NNRs (71%), including coal, chromium, cobalt, copper, iron/steel, magnesium, manganese, natural gas, oil, phosphate rock, potash, rare earth minerals, titanium, uranium, and zinc, had become scarce globally. The planet is not running out of any NNR, but it is running short of many. That is, for an increasing number of NNRs, while there will always be plenty of resources in the ground, but there already aren't enough economically affordable resources in the ground to perpetuate an industrial lifestyle.

Global NNR scarcity is a permanent phenomenon that will persist until industrial civilization comes to an end. With the emergence of many newly industrializing nations in Asia, Africa and Latin America, global NNR requirements have increased meteorically since the beginning of the 21st century. Whereas some 1.5 billion people lived in industrialized and industrializing nations in the late 20th century, that number currently exceeds 5 billion, and most of these people have yet to even remotely approach their full NNR utilization potential.

Global industry's ever-increasing global NNR requirements are manifesting themselves within the context of increasingly constrained—i.e., increasingly expensive and lower-quality—NNR supplies. The cost reductions achieved through improvements in NNR exploration, extraction, production, and processing technologies have been insufficient to offset the higher costs of exploiting the remaining NNR deposits, which are smaller, less accessible, and of lower grade and purity. The earth cannot physically support the current—much less continuously increasing—NNR requirements. In fact, NNR scarcity had become sufficiently pervasive by the onset of the Great Recession to permanently depress future economic growth trajectories and societal wellbeing trajectories at both the domestic and global levels.

The pre-recession episode of pervasive NNR scarcity marked a transition point for the United States. Per capita US NNR utilization peaked in 1999 at 48,427 pounds per US citizen, while total US NNR utilization peaked in 2006 at 7,141,465,500 tons. (Source: Mineral Information Institute, from USGS data)

[image error]Peak US NNR UtilizationGiven the dramatic decreases in both per capita US NNR utilization (17%) and total US NNR utilization (21%) from their pre-recession peaks, it is almost certain that US societal well-being peaked permanently prior to the Great Recession. We should expect the average material living standards in the US will decrease over time, to be followed eventually by a population decrease as well.

[image error]Peak US Societal Wellbeing

The average US material living standard, as proxied by per capita US GDP, peaked in the year 2007 at $43,700, and decreased by 3.4% to $42,200 by 2010 (source). Total US population increased through 2010, and will likely continue to increase until widespread economic distress drives down the birth rate and the childhood survival rate while driving up the death rate.

The historical reality of "continuously more and more," which Americans had experienced since the inception of industrial revolution and had come to take for granted, is giving way to a new reality of "continuously less and less," for reasons that are entirely beyond of their control or ability to fix.

The perception among the American public regarding current "hard times" is therefore accurate. What the vast majority of Americans have yet to understand, however, is that, notwithstanding the increasingly ineffectual and transitory boosts from desperate government and central bank stimulus programs, their well-being as a society will now follow a permanently declining trajectory.

For supporting evidence and references, please request a draft copy of my forthcoming book "Scarcity—Humanity's Final Chapter?" Contact: coclugston at gmail dot com. See also www.wakeupamerika.com.

Bio

Since 2006, Chris has conducted extensive independent research into the area of "sustainability," with a focus on nonrenewable natural resource (NNR) scarcity. NNRs are the fossil fuels, metals, and nonmetallic minerals that enable all of modern industry. His previous experience included thirty years in the electronics industry, primarily with information technology sector companies. Chris received a BA in Political Science from Penn State University, and an MBA in Finance from Temple University.

Published on March 05, 2012 03:00

February 28, 2012

The Lifeboat Hour

Mike Ruppert and I spent the entire hour chatting about the accelerating rate of collapse we are seeing, its causes and what it portends. Maybe it will give you optimism, maybe it will calm you down. Just because the entire planet is on the verge of a nervous background doesn't mean that you have to be.

Mike Ruppert and I spent the entire hour chatting about the accelerating rate of collapse we are seeing, its causes and what it portends. Maybe it will give you optimism, maybe it will calm you down. Just because the entire planet is on the verge of a nervous background doesn't mean that you have to be.

Published on February 28, 2012 03:00

February 26, 2012

A Pile of Straw at the Bottom of the Cliff

There is an old Russian saying: "If Ihad known where I would fall, I would have put down some strawthere." ("Знал бы, гдеупаду—соломки бы подостлал.")It is one of thousands of such sayings that are the repository ofancient folk wisdom. Normally, it is used to express the futility ofattempting to anticipate the unexpected. Here, I am using itfacetiously, to underscore the madness of refusing to anticipate theunavoidable.

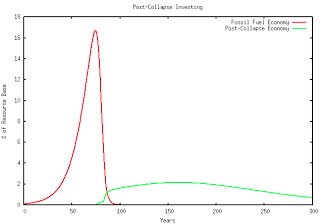

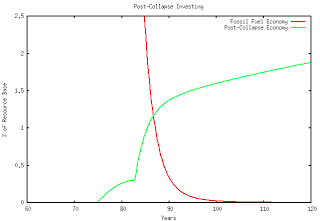

There is an old Russian saying: "If Ihad known where I would fall, I would have put down some strawthere." ("Знал бы, гдеупаду—соломки бы подостлал.")It is one of thousands of such sayings that are the repository ofancient folk wisdom. Normally, it is used to express the futility ofattempting to anticipate the unexpected. Here, I am using itfacetiously, to underscore the madness of refusing to anticipate theunavoidable.I started thinking along these lineswhen I was invited to speak at the annual conference of ASPO(Association for the Study of Peak Oil), which was held in Washingtonin October of last year. It was shaping up to be something of avictory lap for the Peak Oil movement, now that the moment whenglobal conventional oil production reached its historical peak iswell and truly behind us, while the newer unconventional sources ofliquid fuels have turned out to be insufficiently abundant and toocostly both to the pocketbook and the environment. I wanted to usethis opportunity to try yet again to correct what I see as a majorflaw in the narrative of Peak Oil: the idea of a gentle,geologically-driven decline in oil production, which seems quiteunrealistic, which I had detailed in my article "Peak Oil is History" more than a year before. But I also wanted to look beyondit and sketch out some plans that would work after oil productiondives off a cliff, and what it would take to get them off the ground.

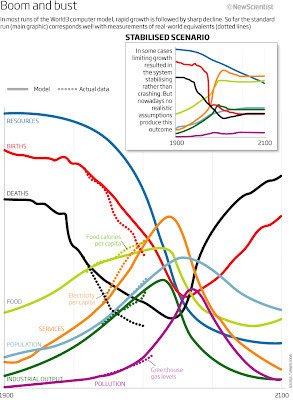

It's all well and good to presentverbal arguments, but words don't stack up against numbers andcurves, so I started looking around for a mathematical model thatwould capture the essence of what I was setting out. I put out a callfor people to contact me if they wanted to collaborate, and was veryhappy to receive an email from Prof. Ugo Bardi of the University ofFlorence, asking what I had in mind. Ugo is an authority on the Club of Rome's much maligned but now vindicated "Limits to Growth" model, having provided it with a recent book-length update.

I wrote back to Ugo:

"I would like to argue that whereasthe method used to model Peak Oil using a Gaussian is reasonable whenlooking at individual oil fields, provinces and countries, it is notreasonable when looking at entire planets, because, unlikeoil-producing provinces and countries in decline, planets can'timport oil, while oil shocks cause industrial economies to collapserather than decline gradually along some geologically constrainedcurve. In [my] article ["Peak Oil is History"] I have a long list of effects such as EROEIdecline, export land effect, etc., to make the case for a stepwisedecline rather than a gradual one.

"If we take our nicesimple Gaussian model of Peak Oil and zoom out sufficiently far, itlooks like an impulse. The peak amplitude and the width are not sointeresting; but we do know what the area under the curve is: theultimate recoverable. This is the "Odulvai Gorge" view ofPeak Oil. Zooming back in, we see that the leading edge is the"growth" edge, influenced by economic growth, technologicalimprovement, ever-wider exploration and so on, and we expect and seeexponential growth. The trailing edge, on the other hand, dominatedby the sudden collapse of industrial economies, due to all thefactors I listed, would be expected to resemble exponential decay,but is so steep that we might as well approximate it as a stepfunction. This is what we generally see when a growth process reachesa limit. Beer-making is one popular example: yeast population andsugar-use increases exponentially, then crashes.

"As oil is the "enabling"energy source, which makes it possible to deplete all other resourcesat a high rate, a stepwise decline in the availability of oil wouldhalt the process of depleting (almost) all other resources (firewoodin rural areas and a few others are the exceptions). So, the furtherthe collapse is delayed, the less there will be left to start overwith, making any attempt to prolong the oil age quite unhelpful. Thisis an ecological argument: the greater the overshoot, the more theeventual carrying capacity is reduced. Therefore, investing in"collapse-proof" schemes and businesses is harmful.

"An alternative is to set resourcesaside (supplies, tools and equipment, designs, skill sets) that canbe rapidly deployed once collapse occurs. Entire turnkey businessschemes can be developed and capitalized, in expectation of collapse.These would 1. hasten collapse by withdrawing resources from thepre-collapse economy (a net positive) and 2. provide for rapiddevelopment of viable post-collapse businesses, such as manual,organic agriculture, sail-based and other non-motorized transport,and so on (also a net positive). Seeing as there is already adistinct lack of good ways to invest money (US "suprime"Treasuries? Gold bullion? African drought-stricken farmland?) thiscan be presented to the investment community as a way to hedgeagainst collapse."

Ugo wrote back:

"Hmmm.... let me see if I understandyour point: you say that a Gaussian is no good; that the descent onthe "other side" of the peak should be much faster than thegrowth. Am I right?

"If so, it is curious that I was workingright on this concept today - and I think I cracked the problem justone hour ago!! Maybe it was already obvious to other people, but itwasn't to me; maybe I am not so smart but, at least I am happy, now.So, I can tell you that you are right on the basis of my systemdynamics model. Descent IS much faster than ascent!!

"When Ireceived your message I was just starting to prepare a post for myblog "Cassandra's legacy" on this subject. So, if you canwait a couple of days, I am going to complete my post and publish it.Then you may give a look to it and we can discuss the matter more indepth. And I'll make sure to cite your post, because I think it isright on target."

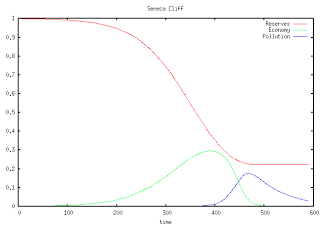

A little while later Ugo published his"SenecaCliff" post. The name came from the following quote fromSeneca:

"It would be some consolation for thefeebleness of our selves and our works if all things should perish asslowly as they come into being; but as it is, increases are ofsluggish growth, but the way to ruin is rapid." LuciusAnneaus Seneca, Letters to Lucilius, n. 91

I wrote back:

"The Seneca Effect is splendid, andwell-named. (Last winter I re-read Seneca's letters to Lucillus whilelaid up with the flu, and found a lot that's relevant.) I think Ishould be able to build on this model to include a few othereffects."

Ugo's post detailed two very simplemodels.

The first model reproduces thecanonical depletion curve, which looks like a Gaussian. It is basedon just a couple of intuitively obvious relationships: firstly, therate at which the resource base is exploited is proportional to boththe size of the resource base and the size of the economy that isbeing used to exploit it; secondly, the economy decays over time(depreciation, entropy, etc.) Set up the initial conditions, run theclock, and out comes the expected curve.

The second model incorporates the ideaof pollution, or bureaucracy, or overhead: the inevitable externalcosts of exploiting the resource. About a third of the flow isdiverted into the pollution bucket, which also decays over time. Thefirst model, it turns out, must be filling the "pollution" bucketby exploiting some other resource, through imports. But since theplanet as a whole imports nothing, the first model is not relevant tomodeling global Peak Oil, and so we have to use the second modelinstead.

I found the Seneca Cliff model veryeasy to reproduce, first using a spreadsheet, then by writing a shortprogram in Python:

I showed my results to Ugo, and hewrote back: "Yes, it seems to be working." I then started addingelements to this model, to see what it might take to "reboot" theeconomy into a post-fossil-fuel, post-industrial "operatingsystem." I made a highly idealized, wildly optimistic assumption: when a criticalmass of people realizes that global Peak Oil has occurred and thatthe global economy is beginning to crash with no hopes of recovery,they will do the right thing: take 10% of the remaining industrialoutput, divert it and stockpile it, to be used to "reboot" into apost-industrial mode once the crash has largely run its course.

There is a problem with this plan: to alayman, global Peak Oil is rather hard to detect, leading to muchconfusion and dithering. Up to the final crash, it looks like aplateau, where oil production refuses to increase in spite ofhistorically high prices.

But ignoring this issue (you have toidealize somewhat, for the sake of clarity, when working withconceptual models), if we start setting aside a "Peak Oil Tithy"around when Peak Oil occurs, and if we deploy all that we'vestockpiled when the fossil fuel economy can no longer support us, thepicture looks like this:

Zooming in, there are two triggers: when the "tithy" starts accumulating (shortly after thepeak), and when it is deployed to build a post-collapse economy (whenthe fossil fuel economy is 50% down from its peak).

The resulting post-collapse economy isquite a lot smaller than the fossil fuel economy, but still largeenough to support a significant portion of the current population,albeit at a much lower standard of living. There might not be indoorheat or hot water, certainly no tropical vacations in wintertime orfruit out of season, no advanced medical treatment and so forth. Butit would still be better than the alternative, or, rather, thecomplete lack thereof.

I presented these graphs at the ASPOconference, where they were greeted with polite silence. There weresome "investors" at the conference, but they were busy attendinga session dedicated to discussing opportunities to invest in thefossil fuel economy. Nobody offered any counterarguments, but thennobody felt compelled to act based on what I said either. Why do youthink that is? Why is that reasonably rational individuals who areable to follow an argument and who are unable to refute it are at thesame time incapable of making the transition from thought to action?What is stopping them? Humans are clearly smarter than yeast, whatdoes that matter if they are incapable of acting any moreintelligently? I will attempt to address this question in asubsequent post.

Published on February 26, 2012 10:18

February 20, 2012

Notes from the Field

Yin Jun[Guest post by Mark. As I keep saying, being poor takes practice.]

Yin Jun[Guest post by Mark. As I keep saying, being poor takes practice.]You hear a lot of talk about relocalization and deindustrialization. The pastoral life, the good old days. How romantic! Reality pays you a visit when your pick-axe hits a rock, a chunk hits your face, and you taste your own blood.

Unaware of it at the time, I was a child of privilege, one of five born to a Chairman of Earth and Space Sciences at a State University in New York. We were all expected to be high achievers. I fulfilled the expectation and put in 32 years as an engineer helping the über-wealthy zip around the skies in personal rocket ships from one golf game to another while chalking it off as business expenses, when all I ever really wanted to do was sit out in the woods and cook some food on a stick over a fire.

In 1994 I acquired a 160 acre tract of land in southeast Kansas, for a price only slightly above chicken feed, as a weekender place to go sit by that fire and decompress from the rat-race. 18 years ago the future didn't look quite so ominous. Reel forward to the present and this full-time back-to-the-land experiment is starting to look like a pretty good idea. Some stark realities become self evident however when you are actually 'living the life'. Talking about it is easy. Doing it is something altogether different. Here is where I wish to convey a few 'notes from the field':

1. You realize after a while it is mostly hard, dirty, repetitive and boring. Mud, blood, shit, sweat, discomfort, disappointment, death. There are rewards, but you have to have a passion for it to endure. People who have grown up ranching already know these things of course, but they don't have to adapt. They know the life.

2. If you create an artificial abundance of anything, Mother Nature will do her best to return things to the status quo. Plant a large garden and you will have more venison than you can eat. Goats are not native to this region, coyotes are. Eagles, hawks, owls, raccoons, possums, foxes and bobcats are also native here. Chickens are not. They will all eat your chickens, given a chance.

3. If you want to eat meat, you have to kill something. It's brutal and unpleasant. Blood is blood, you best get used to it. Warm guts smell bad. They smell different, depending on what you just killed, but they all smell bad. The first time you shove an arm elbow deep in warm guts and blood to tear loose some connective tissue, you are hard pressed to not lose your lunch. It begins to get a bit easier when you have a chilled carcass with the hide peeled off, and the pieces you hack off start to look like something you would buy in a grocery store, but the lifeless eyes continue to stare.

4. Intellectual deprivation. This was unexpected. It doesn't become apparent right away because you're so damned glad to be away from the crush of humanity and the demolition derby approach to getting around. Land is inexpensive in certain regions for a reason. Living elsewhere is much easier (so far). In this case, the regional economy has been in decline for 70 years. The population has declined nearly 80% from its peak, and the brain drain is close to 100%. Most anybody with ambition left long ago, and most youth leave, never to return. It is not hard now to understand why, historically, tribes of 1 to 5 haven't fared well. You need some minimum critical mass of human interaction to be able to survive psychologically, and some degree of specialization and division of labor just to cover all the bases. For those of you considering it, the 'survivalist bunker' approach to dealing with the future would be ill advised. Social interaction is not just something nice, it is an imperative.

Not to be too glum, on the upside there is sunshine, fresh air, fresh meat, eggs, milk, cheese, honey, fruits, nuts, vegetables, abundant wildlife and beautiful scenery. You don't need to 'go to the gym' to stay in shape either.

To peer into the future and see nothing beyond an endless re-run of this hard living is enough to put fear and dread in most hearts. I find it increasingly difficult to believe that dispossessed cubicle dwellers will be able to adapt physically or mentally.

In this setting it is not hard to envision the emergence of a tradition where you take each seventh day off from the grunt work and get together with your friends and neighbors just to celebrate the fact you are still breathing. No deities or voodoo required. Then just for fun, throw a big feast every solstice and equinox and invite everybody. Wait... haven't we been there before?

People tend to think of a 'land of milk and honey' as something idyllic and easy. This land of milk and honey is accessible, tangible and real, but it comes with strings attached.

Published on February 20, 2012 15:05

February 17, 2012

There's No Tomorrow

Here is an excellent new animated short that ties resource depletion, environmental destruction and the end of growth into a single tidy package. For those of you already versed in this subject matter, this might still be good review; for those of you who don't, PLEASE DON'T PANIC! And when introducing this to people, please remind them that they will need a couple of years to come to terms with this, and should try to not panic in the meantime.

Published on February 17, 2012 15:52

February 13, 2012

On The Edge with Max Keiser

As an experiment in unfettered communication, try discussing this interview (or anything else you want) on this Reddit thread. (BTW, Reddit has a happening subreddit: /r/collapse.)

Published on February 13, 2012 02:07

February 5, 2012

The Wheel of Misfortune

Jonas Burgert, RoulettePredating all of the wonderful props atHarry Potter's Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry (HSWW), theoriginal Wheel of Fortune surfaced in Monday Begins on Saturday,a Soviet-era science fiction novella by brothers Strugatsky, where wefind it installed at a the Scientific Research Institute of Sorceryand Magic (НИИЧAВO). It looks like the side of a moving conveyorbelt protruding out of a wall: since it never repeats its course, thewheel must rotate slower than one RPE (revolutions per eternity)meaning that its radius must be infinite, and its edge, projectedinto our physical universe, appears as the edge of a conveyor beltmoving past us.

Jonas Burgert, RoulettePredating all of the wonderful props atHarry Potter's Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry (HSWW), theoriginal Wheel of Fortune surfaced in Monday Begins on Saturday,a Soviet-era science fiction novella by brothers Strugatsky, where wefind it installed at a the Scientific Research Institute of Sorceryand Magic (НИИЧAВO). It looks like the side of a moving conveyorbelt protruding out of a wall: since it never repeats its course, thewheel must rotate slower than one RPE (revolutions per eternity)meaning that its radius must be infinite, and its edge, projectedinto our physical universe, appears as the edge of a conveyor beltmoving past us.Unbeknownst to most of ourcontemporaries, Fortune is actually a deity, like Allah or Jesus, butunlike them she has been worshipped since most ancient times, as Tyche in Greece and as Fortuna in Rome. She continues tobe worshipped in the present times, around the world, but especiallyin the US, where her temples and shrines are everywhere, from thehumble lottery machines at every corner shop, gas station and liquorstore to the casino capitalists who inhabit the glass towers of WallStreet. Millions of mortals supplicate before Tyche daily. Virtuallyunnoticed, the cult of Tyche dominates the religious landscape in theUS: just compare the sizes of the casino buildings in Las Vegas andAtlantic City to the country's largest cathedrals and temples: exceptfor a few mega-churches, the former consistently dwarf the latter.

The essential act of worshipping Tycheis by drawing lots, from which derives the term "lottery."Tyche's promise is that you too may win some day, and this simplepromise is powerful enough to allow her to hold much of thepopulation captive to her every whim, ready to gamble away their lastdollar. Tyche's spiritual solace is that, whatever happens, it isnever your fault, just your luck. Tyche also keeps the peace,allowing us to overcome the envy and rancor we inevitably feelagainst our betters: they succeed not because of their superiority,but because of sheer dumb luck; we could all be just like them, ifonly the all-powerful Tyche would favor us.

Of our two biggest religions, Islam wasfar more successful of purging all other deities, locking up theiridols within the Kaaba at Mecca. (I would love to take a peek insidethe Kaaba to see if Tyche is imprisoned there, except that, being aninfidel, I would get beheaded for even trying.) While the Christianshave attempted to negotiate with Tyche, thinking that there is roomin the universe for both God's will and Tyche's random chance, Islamdid no such thing: Allah is eternal, omnipotent, omniscient,omnipresent and omni-licious, so, if you please, check yourquestioning mind at the gate and prostrate rhythmically in thegeneral direction of Mecca. Wagering is allowed, but only at camelraces, and only among the participating camel jockeys, while"intoxicants and games of chance" are, according to the Quran[5:90-91], "abominations of Satan's handiwork," and so they areharam (verboten). In a strict Moslem society the cult of Tychecan gain no purchase.

Meanwhile, Christianity seems to haveutterly failed at resisting Tyche's charms. In the middle agesFortuna and her wheel were temporarily absorbed into Christian dogma,making her a servant of divine will. But this gambit has failed, aswe recently saw when the Pope tried and failed to answer a simplequestion from a young girl from a war-ravaged land: "Why did Godallow my friends to be killed?" Why does a just and merciful Godallow the murder of innocents? The real answer ("They wereunlucky") cannot be spoken, because it would indicate that Tyche'sauthority supercedes that of the supposed Almighty, causing cognitivedissonance within the flock. At a less intellectual level, salvationcan be seen as an infinitely long winning streak, and the faithfulfeel luckier from being sanctified in the blood of the Lamb. At thealmost completely non-intellectual level of superstition wherein manybelievers dwell, Jesus is a sort of good luck charm. But what all ofthis points to is that, in Christianity, nobody is really in chargeup there, so Tyche feels free to step in and fill the void,incidentally absolving God of any responsibility for what actuallyhappens. He may be all-merciful and love mankind, but then He is not reallythe one issuing the orders on a day-to-day basis. Bewildering, isn'tit?

More bewildering yet, Tyche's claim todominance is not limited to religion or gambling or finance. Inmodern science, randomness (that is, chance, which is Tyche's domain)is at the heart of all explanations of what happens at the level ofelementary particles. The functioning of the transistor—the deviceat the heart of all electronics—is explained by saying that the instantaneous location of any given electron is not a point in space but aprobability distribution, with the actual location picked at random.In spite of this, the observed behavior of transistors is quitedeterministic (except for a bit of hiss which we ignore).

As Einstein famously said, "Goddoesn't play dice with the world." And he was right: it is not Godwho plays dice with the world, it's Tyche, and she is not shy aboutit. The scientists are certainly keeping her busy with the so-calledMonte-Carlo models that are widely used in particle physics, whichare driven by randomness. The gigantic particle accelerators atFermilab and at CERN are the largest prayer wheels ever built,praying that Tyche might show us an exotic particle or two.Impressive though these are, perhaps the largest playground sciencehas given over to Tyche is in evolutionary biology: we are who we arethanks to a sequence of random mutations. Thank you, Tyche, for theopposable thumb, for bipedal locomotion, bifocal vision, and for thefact that we possess language! Without you, not only would we notexist, but life itself would not have evolved out of primordial oozeincessantly zapped by lightning.

I see all of this particularly clearlybecause I am by nature highly resistant to Tyche's charms. The ideaof gambling revolts me, and I have never gambled, or purchased alottery ticket or a raffle ticket, or made a bet. To me, chance andrandomness are noise and garbage. I try to construct pockets ofdifference and meaning within what appears to me as an indifferent anmeaningless universe. Any explanation that hinges on the work ofchance strikes me as one lacking explanatory depth. I do whatever Ican to eliminate chance from my life, and I actually detest the veryidea of luck. This puts me at quite a considerable advantage vis àvis those who waste their energies on Tyche. This has nothing to dowith luck; it just has to do with conserving energy, because that isprecisely what Tyche is (in my opinion): a demon that haunts feebleminds, forcing them to expend their energies in futile pursuits, inorder to keep other, even worse demons at bay.

Such futile pursuits can be quitepleasant (not to me, but then I will concede that I am unusual) whenthere is plenty of energy left to squander. But when that energystarts to run out (along with most other resources on thisovercrowded, depleted, polluted planet), which it is currentlyshowing every sign of doing, then everyone's luck starts torun out at the same time. As the situation goes from bad to worse,people gamble away their savings and drop out of the game. The USlabor market since the financial collapse of 2008 is a case in point:the labor pool has shrunk to the point that something like 10% havelost their jobs, never to gain them back. There is a term for that:it is called a decimation.

Decimation is a Roman military practicethat was used to discipline legions that did not perform well inbattle. Soldiers were organized in groups of ten and drew lots. Outof each group of ten, one comrade drew the shortest stick, and waspromptly bludgeoned to death by the others. This, to them, made perfect sense.In a superstitious culture, victory is a matter of luck, and so toachieve victory, all one needs to do is to identify and purge theunlucky ones, by the luck of the draw. Once they are gone, then bydefinition all those who remain are lucky, and can go on to victoryconfident in the knowledge that Tyche is on their side.

The decimation in the labor market hashad a similar effect: a lot of people are gone and have faded fromview, but the ones who were dismissed as companies "trimmed thefat" are seen as the unlucky ones. Those who remain are, bydefinition, lucky, and try to make the best use of their luck byworking ridiculously long hours. That may work once, but what if thecycle of decimation is to repeat endlessly? The only historical caseof repeated decimation (the Legion of Thebes) was an act ofmartyrdom, and so is not relevant. If a single round of decimationfails to rally the troops to victory, the next one should drive themto mutiny.

The labor market is just one example ofthis sort; the retirement debacle is another. Those people in the USwho have managed to save for retirement are gambling with it, byinvesting it in stocks (whose upside is limited by the economy'sinability to grow) and bonds (whose upside is limited by runawaypublic debt, currency debasement, and eventual sovereign defaultand/or currency devaluation). The financial collapse of 2008 hasdecimated their retirement savings, and yet they are still gamblingwith them. At what point will they refuse to keep playing? When allof their savings are gone, or at some point before then?

At what point does a society made up ofgambling addicts refuse to gamble? Once they have lost everything? Or once it has become clear to them that the game has degenerated into"Heads you lose, tails you lose"? Tyche's charms are appealing onlywhen she isn't cheating. But if you are invited to play, although you(and just about everyone you know) always loses while someperpetually "lucky" group always wins, then that fails to satisfythe gambling urge, and Tyche fades away, to be replaced by the farmore destructive demons of envy and rancor which she previously heldin check. It will be very interesting to see how this will (pardonthe pun) play itself out. Obviously, I am not making any bets.

Published on February 05, 2012 13:46

January 26, 2012

Perfectly Comfortable

I don't particularly like cars. I don'tlike the way they smell, on the inside or the outside. I don't likethe feeling of being trapped in a sheet metal-and-vinyl box, my bodyslowly warping to the shape of a bucket seat. I don't enjoy thevisually unexciting and inhospitable environment of highways or theboredom of spending hours gazing at asphalt markings and highwaysigns. I particularly dislike the insect-like behavior that carsprovoke in people, reducing their behavioral repertoire to that ofants who follow each other around, their heads in close proximity tothe previous insect's rear end. Nor do I enjoy having a mechanicaldependent that I have to feed and house all the time, even though Irarely have need of it. I do sometimes need to use a car, and then Irent one or use one from a car-sharing service that charges by thehour. The most enjoyable parts of that exercise is when I pick it up and when I drop it off. Cars end up costing me a few hundred dollars each year, whichis a few hundred dollars more than I would like to spend on them.

I don't particularly like cars. I don'tlike the way they smell, on the inside or the outside. I don't likethe feeling of being trapped in a sheet metal-and-vinyl box, my bodyslowly warping to the shape of a bucket seat. I don't enjoy thevisually unexciting and inhospitable environment of highways or theboredom of spending hours gazing at asphalt markings and highwaysigns. I particularly dislike the insect-like behavior that carsprovoke in people, reducing their behavioral repertoire to that ofants who follow each other around, their heads in close proximity tothe previous insect's rear end. Nor do I enjoy having a mechanicaldependent that I have to feed and house all the time, even though Irarely have need of it. I do sometimes need to use a car, and then Irent one or use one from a car-sharing service that charges by thehour. The most enjoyable parts of that exercise is when I pick it up and when I drop it off. Cars end up costing me a few hundred dollars each year, whichis a few hundred dollars more than I would like to spend on them.I do like bicycles. They are about themost ingenious form of transportation humans have been able to inventso far. I especially like mine, which I bought second-hand, from afriend, for something like $150. That was about 20 years ago. Itstill has a lot of the original parts: frame, fork, chainrings andcranks, bottom bracket, rims and hubs. The spokes and rims werereplaced once; the cables twice; the freewheel, cassette and chainfive or six times; the tires a dozen times or more; I've lost countof the inner tubes, which don't last long thanks to all the brokenglass on the road from cars smashing into each other. Over time, I'veupgraded various bits. Nice titanium break levers from a used partsbin at a local bicycle school set me back $10. One of the down-tubeshift lever mechanisms fell apart (it was partly made of plastic),and I replaced it with an all-metal one from a nearby bin at the sameestablishment. The original rear derailleur was by Suntour, which nolonger exists, and so I replaced it with a Shimano part, for $60, Irecall. Ruinous expense, that! (The front derailleur is still theoriginal Suntour.) The frame is made of very high qualitychrome-molybdenum alloy of a sort rarely encountered today. Chromeand molybdenum prices have gone up by a lot since then, andsteelmakers have found new ways to cut corners. It survived a ride upand down the East Coast aboard a sailboat, exposed to the elements,without a problem. It looks like a beat-up, rusty old road bike—notsomething bicycle thieves normally find interesting—and that'sexactly how a bicycle should be made to look even when it is new.

I ride something like 7 km just aboutevery weekday of the year. Sometimes I ride quite a bit farther,spending half a day meandering through the countryside or along thecoast. I've ridden as much as 160 km in one day; that was a bittiring. I rarely take the shortest path, preferring meandering bikepaths that go through parks and along the river. I do ride throughtraffic quite a bit of the time, and have developed a style forkeeping safe. I pay minimal attention to traffic signals and lights(they wouldn't be needed if it weren't for cars) and mostly just payattention to the movements of cars. (Traffic lights are sometimesuseful in predicting the behavior of cars, but not reliably, and notso much in Boston.) I also tend to take up a full lane whenever abicycle lane is not available (cars are not a prioritized form oftransportation, to my mind). A person who is in a hurry, here inBoston, would get there sooner by riding a bicycle. I understand thatthis annoys certain drivers quite a lot, raising their bloodpressure. Perhaps the elevated blood pressure will, in due course,get them off the road, along with their cars, freeing up the spacefor more bicycles.

In the summer, my riding attireconsists of a tank-top, shorts, and flip-flops (I've tried variouscombinations of pedals with toeclips, clipless pedals and bicycleshoes with cleats, and eventually settled on the most basic pedalsavailable and flip-flops. I've also experimented with paddedbicycling shorts and jerseys made of Lycra, and found them tooconfining. Also, I just couldn't get over the feeling that Ishouldn't wear such outfits, no more than I should be going around intights and a tutu, and so I went back to wearing hiking shorts. Butit can be a fine show when Balet russe comes rolling through town.When it rains, I put on a Gortex bicycle jacket that evaporates thesweat while keeping the rainwater out. The hood goes under thehelmet, keeping my head dry as well.

The bicycling outfit gets morecomplicated in wintertime. The Gortex jacket is still there, butunderneath it is a hoodie, under that a wool shirt and thermalunderwear (microfiber works best). The shorts are replaced withjeans, with Gortex zip-on pants over them for messy weather. Theflip-flops are replaced with insulated, waterproof half-boots, withtwo layers of wool socks. Add ski gloves and a ski mask, and theoutfit is complete.

Oddly enough, bicycling on a frosty butdry winter day is even more enjoyable than on a balmy summer day.Firstly, in the winter cooling is not an issue, so I can ride as fastas I want without breaking a sweat. If I start feeling too warm, Ican unzip the jacket partway and get all the cooling I want.Secondly, there is the realization that bicycling in wintertime ismore comfortable than walking, since I can generate as much heat as Ineed to keep warm simply by going faster. The one somewhat unpleasantpart of winter riding is the wind: cold winter air is a lot denserthan warm summer air: a 20 km/h headwind is hard to pedal against inthe summer, but much harder in the winter. (I recently rode acrosstown in a gale, and it was not unlike a mountain climb, grinding awayin the lowest gear. The ride back was all downwind, and I was flying,riding the brakes the entire way.)

Snow and ice present an interesting setof challenges to a two-wheeled vehicle. I've experimented withstudded tires, fat cyclocross tires with deep treads and regular roadtires. Road tires won. Studded tires on both front and back are ahuge performance killer, making a fast road bike into more of astationary exercise bike. Putting the studded tire just on the front(which is where it is really needed the most, since the rear canfishtail all it wants without compromising stability) helps quite alot. But overall, studded tires create a false sense of security; itis better, I have found, to keep the regular road tires on and simplylearn to recognize and adjust to the conditions.

High-pressure road bicycle tires havetiny contact patches, and apply tremendous pressure to the roadsurface—enough to indent packed snow, creating side-to-sidetraction. It's still not possible to bank steeply, but it is quitepossible to keep balance by slowing down. Fore-and-aft traction isnot quite as good, making rapid acceleration and braking unlikely. Ona slippery surface, the game becomes to avoid breaking frictionbetween the road and the tire. Tires with a deep tread seem to workwell on mud, but do not seem to help at all on snow, because thetread becomes packed with compacted snow, causing a lot of rollingresistance but not much traction. With regular road tires, the onlytruly frictionless surfaces I have found so far are smooth icecovered by water and oiled steel plates. When I encounter either ofthese, I get off and walk, having once wiped out quite badly on anoiled steel plate, in the middle of summer, in fine weather.

If any of this seems strange to you,then there may be something funny going on inside your head and youshould get it checked out. Around the world, for over a century,people everywhere have used the bicycle to get around in every kindof climate and weather. There are year-round bicyclists in theSahara, as well as in Edmonton, Alberta. Bicycling year-round is verymuch a solved problem everywhere. Here in Boston I know dozens ofpeople who commute by bicycle year-round, and I see hundreds ofpeople out on bicycles, every day, at all times of the year.

And yet with just about any randomgroup of people I encounter the idea of bicycling through winter isregarded as very strange: somewhere between suicidal and heroic. (Thefact that driving a car is far more dangerous, and suicidal onmultiple levels, does not seem to register with most people.) Whatcan I say? To each his own. As for me, I am perfectly comfortableriding a bicycle year-round.

Published on January 26, 2012 15:00

Dmitry Orlov's Blog

- Dmitry Orlov's profile

- 48 followers

Dmitry Orlov isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.