Dmitry Orlov's Blog, page 29

January 8, 2012

Dance of the Marionettes

It's election season in the US, whichmeans that I have the unwelcome task of wading throughwell-intentioned though off-topic comments devoted to thingspolitical: who might be the next president, and whether or not itmatters who the next president is (it doesn't). And rather than bearit quietly, I thought I'd say something about it.

It's election season in the US, whichmeans that I have the unwelcome task of wading throughwell-intentioned though off-topic comments devoted to thingspolitical: who might be the next president, and whether or not itmatters who the next president is (it doesn't). And rather than bearit quietly, I thought I'd say something about it.Electioneering in the US is steadilyexpanding to fill more and more time and space even as it providesworse and worse results with each election cycle. The Congress ismade of some of the least popular people on earth, who are manifestlyincapable of achieving anything useful. They do seem quite ready andwilling to pass laws that erode human rights and enhance the powersof the police state, but this is because they are paranoid. Perhapstheir one point of consensus is that sooner or later theirconstituents will want to open fire on them.

Still, the elections provide aspectacle, the media are conditioned to lavish attention on thecandidates, and the people, being weak-willed, are once againbeguiled into thinking that it matters who gets elected. A few yearsof Obama impersonating Bush should have taught them that it doesn'tmatter who the Prisoner of the White House is. Likewise, watching thesad spectacle of Congress trying to raise the debt limit or to reignin runaway deficit spending should have taught them that thisinstitution is no longer functional. (The US is about to bump upagainst the debt limit again; does anyone even care?) All of thisshould have been enough to make it clear to just about everyone thatwondering what might be different if, say, Ron Paul got electedpresident, is like wondering what might be different if the moon weremade of a different kind of cheese—your favorite kind, of course.

Leaving aside the meaningless questionof who the next Figurehead in Chief might be, let's look briefly atwhat is perhaps the most corrupt institution the US has: the USSenate. Everyone knows that senate seats are for sale: as soon as asenator gets elected, he starts fund-raising, to finance hisreelection campaign. Since each state, whether huge or puny, gets twoseats, these are variously priced: the two seats for a large, populousstate, like California or Texas, are very expensive, while the two seatsfor the puny State of Potatoho or some such, with its zero millioninhabitants, are more reasonably priced. Since the senatorsthemselves decide nothing and are simply mouthpieces to the moneyedinterests which buy their seats, and since this is a very dividedcountry, they are unable to achieve compromise, making the Senatecompletely useless as a deliberative body.

Let's face it: the senators are justmarionettes controlled by giant bags of money. Their seats aredefinitely for sale, all of them, all the time. But then an odd thinghappened about a month ago: the ousted Illinois Governor Rod Blagojevichwas sentenced to 14 years in prison for allegedly attempting to sellthe senate seat that was vacated when Obama was elected president. Itseems like a stiff penalty for something that is a routine, dailyoccurrence, does it not? It is especially odd since other miscreantswho actually caused serious damage, like former senator Jon Corzine,who looted investors' accounts to cover his gambling debts in thefutures market, are still at large. What set Blagojevich apart is that heviolated a taboo. Just like any normal criminal syndicate, the USSenate has rules by which the members preserve their positions andkeep each other in check. As with a criminal syndicate, these ruleshave nothing to do with serving the public interest. One of theserules is that it is not allowed to sell a senate seat if it isunoccupied. Essentially, senators get to sell senate seats, governorsdon't. It is a tribal taboo: "Of course we can have sex with ourunderage daughters—we all do it—but not when they aremenstruating! We are all good decent God-fearing Troglodytes!" Rod Blagojevichis the exception that proves the rule: senate seats are for sale.

It stands to reason, then, that the wayto influence this political system, in its current advanced state ofdegeneracy, is not through the political process, which is just a proforma activity that determines nothing. Armed with the understandingthat it doesn't matter who gets elected, we should ignore theelections altogether. To get the government to respond, it is far more effective to organizearound issues, pool resources, and hire lobbyists.

As for the rest of us, who do not havethe means to hire lobbyists, there are still a few things we can do:we can starve the system by withholding resources from it, and we canbleed the system by extracting payments from it. If we are clever, wecan also find ways to frustrate the system by artificially generatingcomplexity. The system has been gamed to our disadvantage. We are notgoing to win by playing along. But we all win whenever we refuse toplay the game.

If you simply can't resist thetemptation to play the game, don't play it to win. Play it strictlyfor the entertainment value. Ignore the front-runners and focus onall the amusing types that have zero probability of being elected.Encourage them, give them airtime and attention. And if anybodywonders why their candidacy matters, use the opportunity to explainto them why none of these political marionettes matter at all.

If you simply can't resist thetemptation to play the game, don't play it to win. Play it strictlyfor the entertainment value. Ignore the front-runners and focus onall the amusing types that have zero probability of being elected.Encourage them, give them airtime and attention. And if anybodywonders why their candidacy matters, use the opportunity to explainto them why none of these political marionettes matter at all.

Published on January 08, 2012 11:21

January 6, 2012

Where did the money go?

[A timely guest post from Gary, with all the anti-Iranian sabre-rattling going on. Spurred on by its political parasitic twin Israel, Washington seems poised to shoot itself right in the wallet. I believe that's called a "beauty shot."]

[A timely guest post from Gary, with all the anti-Iranian sabre-rattling going on. Spurred on by its political parasitic twin Israel, Washington seems poised to shoot itself right in the wallet. I believe that's called a "beauty shot."] The lesson that the United States desperately needs to learn is that their trillion-dollar-a-year military is nothing more than a gigantic public money sponge that provokes outrage among friends and enemies alike and puts the country in ill repute. It is useless against its enemies, because they know better than to engage it directly. It can never be used to defeat any of the major nuclear powers, because sufficient deterrence against it can be maintained for relatively little money. It can never defuse a popular insurgency, because that takes political and diplomatic finesse, not a compulsion to bomb faraway places. Political and diplomatic finesse cannot be procured, even for a trillion dollars, even in a country that believes in extreme makeovers. As Vladimir Putin put it, "If grandmother had testicles, she'd be a grandfather."

Reinventing Collapse, 2nd ed., p. 41

Military Keynesianism and America's Declining Infrastructure

In August 2007, the nation was stunned by the collapse of a major Minneapolis bridge, killing thirteen. The bridge had been rated structurally deficient by the U.S. government as far back as 1990, and it was only one of 72,868 bridges (12.1%) across the country with that rating. They also rated 89.024 bridges (14.8%) as functionally obsolete. Here closer to my home the eighty year old Champlain Bridge, also known as the Crown Point Bridge, was closed in October 2009 due to extensive corrosion of two structural piers. At least it was condemned before it fell down. Two years later a replacement bridge has been completed, but not without substantial inconvenience and economic loss to business and workers on both sides of the bridge. People were forced to take a ferry during reconstruction. The DOT states the average design life of US bridges is 50 years with an average current age of 43. The American Society of Civil Engineers estimates that it would take nearly $930 billion to fix the country's failing bridges and roads over the next five years (www.infrastructurereportcard.org/fact-sheet/bridges). With estimated spending of $380.5 billion, they predict a shortfall of $549.5 billion.

Where did all the money go? The recently deceased Chalmers Johnson called it "Military Keynesianism". For those who don't follow arcane economics lingo, Keynes was a British economist who said that in a period of slow or declining economic growth (recession or depression), that government spending was needed to "prime the pump" of the economy. The US recovery from the Great Depression with help from WWII military spending gave credence to this analysis. Except now we have permanent Military Keynesianism.

Johnson cites an incredible statistic from the late Seymour Melman, the Columbia University advocate of military conversion, and the "peace dividend". "By 1990, the value of the weapons, equipment, and factories devoted to the military was 83% of the value of all plants and equipment in American Manufacturing. From 1947-1990 the combined US military budget amounted to $8.7 trillion...Military industries crowd out the civilian economy (ed-and other government spending like bridges) and lead to severe economic weakness." Consider that the US military is now spending over $1 trillion per year including all black and related expenses, which is more than the entire rest of the world combined. The next biggest spender is China at $91.5 billion according to Chinese figures. Johnson summarizes, "Devotion to military Keynesianism is, in fact, a form of slow economic suicide."

But isn't war good for the economy as former President George W. Bush told Argentine President Kirchner in Oliver Stone's recent movie "South of the Border?" Johnson quotes historian Thomas Woods, "According to the US DOD, during the four decades from 1947 through 1987 it used (in 1982 dollars) $7.62 trillion in capital resources. In 1985 the Dept of Commerce estimated the value of the nation's plant and equipment and infrastructure at just over $7.29 trillion. In other words, the amount spent over that period could have doubled the American capital stock or modernized and replaced its existing stock."

Johnson cites a study by economist Dean Baker of CEPR in 2007 that concludes, "In fact most economic models show that military spending diverts resources from productive uses, such as consumption and investment, and ultimately slows economic growth and reduces employment." Why would this be? Think about nuclear weapons. The best possible use for them is not to use them at all. At the peak the US had 32,500 nuclear weapons. Think about the massive cost of something that then (thankfully) sits on the shelf and provides no use to anyone.

Finally Johnson quotes Harvard economics professor Benjamin Friedman, "Again and again it has always been the world's leading lending country that has been the premier country in terms of political influence, diplomatic influence, and cultural influence...we are now the world's biggest debtor country, and we are continuing to wield influence on the basis of military prowess alone." Think about that when you pay your family's $10,000 per year contribution to the Iraq and Afghanistan wars.

Back in the 1980's Gorbachev cut Soviet military spending, and predicted that the US would continue to spend itself into oblivion. Who will stop the madness of military Keynesianism? Obomber or Romney? LOL. Johnson concludes, "Our short tenure as the world's "lone superpower" has come to an end." All that's left is for the fat lady to sing, when the US goes broke. It won't be long now.

All quotes from Dismantling the Empire, by Chalmers Johnson, Metropolitan Books/Henry Holt and Co. 2010

Published on January 06, 2012 17:00

January 4, 2012

The Rise of Tricycle Pushcarts

[Guest post by Albert. I spent some time as Albert's guest on the little island of which he writes. It is one of my favorite places in the world.]

[Guest post by Albert. I spent some time as Albert's guest on the little island of which he writes. It is one of my favorite places in the world.] "Even in backward mining communities, as late as the sixteenth century more than half the recorded days were holidays; while for Europe as a whole, the total number of holidays, including Sunday, came to 189, a number even greater than those enjoyed by Imperial Rome. Nothing more clearly indicates a surplus of food and human energy, if not material goods. Modern labor-saving devices have as yet done no better.

Lewis Mumford, Myth of the Machine : Technics and Human Development, 1967.

In rural México, the number of holidays competes with the number of workdays to see which will find more space on the calendar. Not that the people don't work, mind you, just that they like to keep hours at any given task as brief as possible, to maintain perspective. As in most agricultural regions of the world, diversity and entrepreneurship is ingrained. When times are especially tight, this instinct goes into overdrive.

I have been wintering in a small Mayan fishing village that is part of a natural reserve and like most villages in México it is laid out on a New England-style town grid. There were no ancient Roman master planners or 1950's city engineers that surveyed these grids. Nearly all were spontaneous extensions from a single spine road that sent off perpendicular ribs at regular intervals, and those sent off cross-lanes at approximately the same intervals—usually 6 or 8 homes on a side—that created the matrix. Grids like these, as the Egyptians, Greeks, Chinese and Romans understood, enhance the interactions amongst people and encourage a free flow of products, services and information.

Living on one such street, all of them unpaved here, I have noticed a discernible uptick in the number and variety of pushcarts. Here they are called tricyclos. In other places—Denmark or Holland, for instance—modern pushcarts are "cargo cycles." They can take different forms but the most common is what is known in the bike world as tadpole or front-load trike—2 wheels in front and 1 wheel in the back. These are ideal for food vendors or pedicabs which require frequent interactions with the scene on the street.

A world leader in trike evolution is Christiania, the 800-member urban ecovillage in Copenhagen. Their company, Christianabikes began in 1976 as a small cottage industry to support the alternative community. Today Christianabikes is transnational in reach and constantly improving its designs. For long-hauls, it has low-slung cargo bikes. For vendors like those in Mexico, it has a simple tadpole design that can be customized to meet virtually any use. What we see in Mexico are mostly Chinese-made clones of Christiania's original design, or Mexican fabrications of the Chinese fabrications tacked together in local welding shops. Creations like these, which date back a century or more, should be acknowledged to be 'open source' by now.

What struck me is that I cannot recall a time in the past decade that I have been observing these vendors when there were more of them. Call it a sign of the times, but every few hours another passes by the front of my house, shouting out what he or she is selling. In the morning its newspapers and fresh, hand-made tortillas. Around lunchtime is it fresh garden vegetables, epizote, bread and other kinds of unprepared food. There might be a tricycle for fruits and juices, another for tomatoes, onions and peppers, another for potatoes, beans and rice. By late afternoons they may pass by with fresh sweetbreads, steaming hot tamales, or corn on the cob.

A man with his tricycle grinding stone offers to sharpen machetes, knives, scissors, shovels, or any other sharp objects. A man with a blender (12V but it could as easily be pedal-powered) makes cups of shaved ice with sweet corn or coconut.

You can buy a tricycle brand-new, assembled, already painted in taxi colors of orange and white, and be ready to take a fare straight from hardware store to wherever they are going. The price of a new Chinese-built trike is 3200 pesos, about US$229.32 at today's rates. The board that goes across the bars for a seat was salvaged from the trash at no cost, but perhaps some cushioned fabric is sewn over to help you through the potholes. Typically a fare pays 20 pesos ($1.43) for up to a 10-block ride.

I asked a tortilla vendor who plies a regular daily afternoon route how much he sells in an average day. "100 kilos" is what he said. His corn tortillas sell for a 3-peso mark-up over the tortilla factory (and there are three of them within a 5-block radius). So if he sells 100 kg, he makes 300 pesos per day, enough to pay for the tricycle in just under 11 days. Perhaps his wife has a masa roller and automated oven at home and he makes his own tortillas and the margin is even better.

Stopping by the largest of the tortilla factories in town — a one-room addition to a family home, which now employs three women from outside the family to turn corn meal masa into machine-stamped tortillas — I inquired how many tortillas they make in a typical day. "Ocho o nueve," she said, meaning eight or nine metric tons — 8000 to 9000 kilos — and remember, this is just one of three within a short distance, and many people prefer to make their own at home. The entrepreneurial drive explores for available niches and fills them. Many of these factories supply restaurants and grocery stores. Retail home sales pass through bulk buyers at the tortilleria, like my local trike man, who do just fine with the small margin people are willing to pay for the convenience of not walking around the corner.

I noticed that my man sometimes gets lucky and lands a really big sale, however. Maybe someone is throwing a big party (and this happens often) and needs 20 kg. Or a tendajón finds itself short on a holiday weekend and buys 50 kg. His route is pretty small, just a few blocks, but if his son could run his trike in the mornings, or a second trike in the afternoon when he is making his rounds, perhaps he could extend his family's range and double their earnings. Then again, as I've seen, he's not interested in that, preferring to live quite adequately on 300 pesos per day ($21.50) in a town where the average unskilled worker makes even less than that. Or perhaps he has another job already and is just enlarging the family's income by putting in a few extra hours while schmoozing with his neighbors.

For me, I'd rather save 3 pesos and ride my bike a couple blocks to the tortilleria, but that's mainly because, being a writer, I need excuses to force myself out of my chair. As times have become tougher for average people, I've also noticed more homes along my bike route opening their front rooms to make tendejóns or comidas economicas. A comida economica provides a home-cooked meal with table service, giving the buyer a plate of whatever the family is making that day. A tendejón is an informal home store. It might have home-grown pigs, chickens or eggs for sale, or garden produce. It shares the same root word, tener (to have), as the more formal store or mini-mart (tienda), but whether for legal reasons or just wanting to keep it more neighborly, a tendejón is an unpredictable collection of wares in someone's living room, next to their Christmas tree and fluorescent blinking statute of the Virgin of Guadelupe.

Between the tendejón and the tienda lie the more formal abarrotes, or package stores, which usually sell cold beer, insect repellent and junk food. These are usually under a residence or in an adjoining building to the family's principal dwelling. There are one or more abarrotes, tendejóns and tiendas on nearly every block.

Tricyclos are a common sight in much of Yucatán Peninsula, as they are in Asia, Africa, South America and other parts of the two-thirds world. In the United States you mention a tricycle and people think of Monty Python or Laugh-In. In the global south they are multifunctional and ubiquitous. You see them as fishermen's friends, beach-roving gear-buckets for surfers, portable crepe parlors, bellhop cabin service, and the poor man's moving van.

Low-tech Magazine, an on-line compendium, describes many novel uses for pedal power, from archival scans of Sears Catalog pages circa 1892 to a modern recumbent cargo quads. Corn grinding, water pumping and sewer-system cleaning are all potentially portable, pedal-powered services. These are niches that will likely be explored in the South far sooner than when people in North finally decide to come down off of their high horses and get a third wheel.

Published on January 04, 2012 17:00

January 2, 2012

A Dismal Public Affair

This morning I was honored to participate in a panel discussion on what the near future holds with an illustrious panel: Richard Heinberg, Nicole Foss, James Howard Kunstler and Noam Chomsky. And it turned out really dismal, if you ask me! The overall message seems to have been that it doesn't matter what any of us say, because so few people are able to take in such bad news without becoming despondent, so we might as well just let Chomsky ramble on like he always does, as a sort of case in point. And of course the moderator just had get up Kunstler's nose with the usual "so this is all doom and gloom, isn't it?" sort of comment. The one funny bit is where Chomsky calls Daniel Yergin "a very serious analyst" right after Kunstler says that he is the oil industry's prostitute.

Do you want some good news? Here it is: Russia's GLONASS satellite navigation system is fully operational, finally, so we no longer have to rely solely on the Pentagon's GPS to tell us where we are. In fact, the two systems work and play well together.

Do you want some good news? Here it is: Russia's GLONASS satellite navigation system is fully operational, finally, so we no longer have to rely solely on the Pentagon's GPS to tell us where we are. In fact, the two systems work and play well together.

Published on January 02, 2012 17:00

December 15, 2011

A Conversation About Europe

[Première publication sur Orbite.info]

I came upon Dmitry Orlov's writings—as with most good things onthe Internet—by letting chance and curiosity guide me from link tolink. It was one of those moments of clarity when a large number ofconfusing questions find their answer along with their correctformulation. For example, the existence of fundamental similaritiesbetween the Soviet Union and the United States was for me a vagueintuition, but I was unable to draw up a detailed list as Dmitry hasdone. One must have lived in two crumbling empires in order to beable to do that.

I must say that my enthusiasm was not sharedby those around me, with whom I have shared my translations. It'sonly natural: who wants to hear how our world of material comfort,opportunity and unstoppable individual progress is about to collapseunder the weight of its own expansion? Certainly not the post-wargeneration high on exuberant growth of the postwar boom (1945-1973),well established in their lives of average consumers since the 1980s,and willing to enjoy a hedonistic age by remaining convinced thatdespite the economic tragedies ravaging society around them, theiryoung children will benefit from more or less the same well-padded,industrialized lifestyle. The generation of children is morereceptive to the notion of economic decline—though to varyingdegrees, depending on the decrease of their purchasing power andlevel of depression in their field of employment (if they have one).

It would be wrong to shoot the messenger who brings badnews. If you read Dmitry carefully, scrupulously separating thefactual bad news, which are beyond his control, from his views onwhat can be done to survive and live in a post-industrial world, youwill find evidence of strong optimism. I hope that in this he isright.

Whatever our views on peak oil and its consequences—orour appetite for scary prophecies—we can find in Dmitry Orlov freshideas on how to conduct our lives in a degraded economic andpolitical environment, reasons to seek unlikely yet fruitfulrelations with our fellow men, or the most effective approach to thefrustrating political and media chatter and the honeyed whisper ofcommercial propaganda (shrug, turn around and go on with your life).

Tancrède Bastié

TB: What difference do you seebetween American and European close future?

DO: European countries are historicalentities that still hold vestiges of allegiances beyond themonetized, corporate realm, while the United States was started as acorporate entity, based on a revolution that was essentially a taxrevolt and thus has no fall-back. The European population is lesstransient than in America, with a stronger sense of regionalbelonging and are more likely to be acquainted with their neighborsand to be able to find a common language and to find solutions tocommon problems.

Probably the largest difference, andthe one most promising for fruitful discussion, is in the area oflocal politics. European political life may be damaged by moneypolitics and free market liberalism, but unlike in the United States,it does not seem completely brain-dead. At least I hope that it isn'tcompletely dead; the warm air coming out of Brussels is oftenindistinguishable from the vapor vented by Washington, but betterthings might happen on the local level. In Europe there is somethingof a political spectrum left, dissent is not entirely futile, andrevolt is not entirely suicidal. In all, the European politicallandscape may offer many more possibilities for relocalization, fordemonitization of human relationships, for devolution to more localinstitutions and support systems, than the United States.

TB: Will American collapse delayEuropean collapse or accelerate it?

DO: There are many uncertainties to howevents might unfold, but Europe is at least twice as able to weatherthe next, predicted oil shock as the United States. Once petroleumdemand in the US collapses following a hard crash, Europe will for atime, perhaps for as long as a decade, have the petroleum resourcesit needs, before resource depletion catches up with demand.

The relative proximity to Eurasia'slarge natural gas reserves should also prove to be a major safeguardagainst disruption, in spite of toxic pipeline politics. Thepredicted sudden demise of the US dollar will no doubt beeconomically disruptive, but in the slightly longer term the collapseof the dollar system will stop the hemorrhaging of the world'ssavings into American risky debt and unaffordable consumption. Thisshould boost the fortunes of Eurozone countries and also give somebreathing space to the world's poorer countries.

TB: How does Europe compare to theUnited States and the former Soviet Union, collapse-wise?

DO: Europe is ahead of the UnitedStates in all the key Collapse Gap categories, such as housing,transportation, food, medicine, education and security. In all theseareas, there is at least some system of public support and someelements of local resilience. How the subjective experience ofcollapse will compare to what happened in the Soviet Union issomething we will all have to think about after the fact. One majordifference is that the collapse of the USSR was followed by a wave ofcorrupt and even criminal privatization and economic liberalization,which was like having an earthquake followed by arson, whereas I donot see any horrible new economic system on the horizon that is readyto be imposed on Europe the moment it stumbles. On the other hand,the remnants of socialism that were so helpful after the Sovietcollapse are far more eroded in Europe thanks to the recent wave offailed experiments of market liberalization.

TB: How does peak oil interact withpeak gas and peak coal? Should we care about other peaks?

DO: The various fossil fuels are notinterchangeable. Oil provides the vast majority of transport fuels,without which commerce in developed economies comes to a standstill.Coal is important for providing for the base electric load in manycountries (not France, which relies on nuclear). Natural gas(methane) provides ammonia fertilizer for industrial agriculture, andalso provides thermal energy for domestic heating, cooking andnumerous manufacturing processes.

All of these supplies are past theirpeaks in most countries, and are either past or approaching theirpeaks globally.

About a quarter of all the oil is stillbeing produced from a handful of super-giant oil fields which werediscovered several decades ago. The productive lives of these fieldshave been extended by techniques such as in-fill drilling and waterinjection. These techniques allow the resource to be depleted morefully and more quickly, resulting in a much steeper decline: the oilturns to water, slowly at first, then all at once. The super-giantCantarell field in the Gulf of Mexico is a good example of such rapiddepletion, and Mexico does not have many years left as an oilexporter. Saudi Arabia, the world's second-largest oil producer afterRussia, is very secretive about its fields, but it is telltale thatthey have curtailed oil field development and are investing in solartechnology.

Although there is currently an attemptto represent as a break-through the new (in reality, not so new) hydraulic fracturingand horizontal drilling techniques for producing natural gas fromgeological formations, such as shale, that were previously consideredinsufficiently porous, this is, in reality, a financial play. Theeffort is too expensive in terms of both technical requirements andenvironmental damage to pay for itself, unless the price of naturalgas rises to the point where it starts to cause economic damage,which suppresses demand.

Coal was previously thought to be veryabundant, with hundreds of years of supply left at current levels.However, these estimates have been reassessed in recent years, and itwould appear that the world's largest coal producer, China, is quiteclose to its peak. Since it is coal that has directly fueled therecent bout of Chinese economic growth, this implies that Chineseeconomic growth is at an end, with severe economic, social andpolitical dislocations to follow. The US relies on coal for close tohalf of its electricity generation, and is likewise unable toincrease the use of this resource. Most of the energy-denseanthracite has been depleted in the US, and what is being producednow, through environmentally destructive techniques such asmountaintop removal, is much lower grades of coal. The coal is slowlyturning to dirt. At a certain point in time coal will cease toprovide an energy gain: digging it up, crushing it and transportingit to a power plant will become a net waste of energy.

It is essential to appreciate the factthat it is oil, and the transport fuels produced from it, thatenables all other types of economic activity. Without diesel forlocomotives, coal cannot be transported to power plants, the electricgrid goes down, and all economic activity stops. It is also essentialto understand that even minor shortfalls in the availability oftransport fuels have severe economic knock-on effects. These effectsare exacerbated by the fact that it is economic growth, not economicdécroissance [Fr., "de-growth"] (which seems inevitable, given the factors describedabove) that forms the basis of all economic and industrial planning.Modern industrial economies, at the financial, political andtechnological level, are not designed for shrinkage, or even forsteady state. Thus, a minor oil crisis (such as the recent steadyincrease in the price of oil punctuated by severe price spikes)results in a sociopolitical calamity.

Lastly, it bears mentioning that fossilfuels are really only useful in the context of an industrial economythat can make use of them. An industrial economy that is in anadvanced state of decay and collapse can neither produce nor make useof the vast quantities of fossil fuels that are currently burned updaily. There is no known method of scaling industry down to boutiquesize, to serve just the needs of the elite, or to provide lifesupport to social, financial and political institutions thatco-evolved with industry in absence of industry. It also bearspointing out that fossil fuel use was very tightly correlated withhuman population size on the way up, and is likely to remain so onthe way down. Thus, it may not be necessary to look too far past thepeak in global oil production to see major disruption of globalindustry, which will make other fossil fuels irrelevant.

TB: How is post-collapse Russiadoing ? Ready for its second peak ?

DO: Russia remains the world's largestoil producer. Although it has been unable to grow its conventionaloil production, it has recently claimed that it can double its oilendowment by drilling offshore in the melting Arctic. Russia is andremains Europe's second largest energy asset. In spite of toxicpipeline politics (which have recently been remedied somewhat by theconstruction of the Nordstream gas pipeline across the Baltic) it hashistorically been the single most reliable European energy supplier,and shows every intention of remaining so into the future.

TB: Is there hope for a safe,harmless European decline, or is any industrial society just bound tocollapse at once when fuel runs out?

DO: The severity of collapse willdepend on how quickly societies can scale down their energy use,curtail their reliance on industry, grow their own food, go back tomanual methods of production for fulfilling their immediate needs,and so forth. It is to be expected that large cities and industrialcenters will depopulate the fastest. On the other hand, remote,land-locked, rural areas will not have the local resources to rebootinto a post-industrial mode. But there is hope for small-to-middlingtowns that are surrounded by arable land and have access to awaterway. To see what will be survivable, one needs to look atancient and medieval settlement patterns, ignoring places that becameoverdeveloped during the industrial era. Those are the places to moveto, to ride out the coming events.

TB: I remember my grandmothertelling me about the German occupation, when urban and suburbandwellers flocked into country towns every Sunday with empty cases,eager too find some food to buy from the local farmers, hoping backin a train the same day. Is there any advantage in living in a city,in a post-collapse era, rather than in the countryside?

DO: Surviving in the countrysiderequires a different mindset, and different set of skills thansurviving in a town or a city. Certainly, most of our contemporaries,who spend their days manipulating symbols, and expect to be fed fordoing so, would not survive when left to their own devices in thecountryside. On the other hand, even those living in the countrysideare currently missing much of the know-how they once had forsurviving without industrial supplies, and lack the resources toreconstitute it in a crisis. There could be some fruitfulcollaboration between them, given sufficient focus and preparation.

TB: Can we grow sufficient food withlow technology, low energy methods, out of highly exhausted, highlypolluted farmland ? It seems we might end up in a worse farmingsituation than our ancestors just two or three generations ago.

DO: That is certainly true. Add globalwarming, which is already causing severe soil erosion due totorrential rains and floods, droughts and heat waves in other areas.It is likely that agriculture as it has existed for the past tenthousand years will become ineffective in many areas. However, thereare other techniques for growing food, which involve setting upstable ecosystems consisting of many species of plants and animals,including humans, living together synergistically. What will ofnecessity be left behind is the current system, where fertilizers andpesticides are spread out on tilled dirt (rather than living soil) tokill everything but one organism (a cash crop) which is thenmechanically harvested, processed, ingested, excreted, and flushedinto the ocean. This system is already encountering a hard limit inthe availability of phosphate fertilizer. But it is possible tocreate closed cycle systems, where nutrients stay on the land and areallowed to build up over time. The key to post-industrial humansurvival, it turns out, is in making proper use of human excrementand urine.

TB: If cities or big towns survivecollapse, what will be their core activities? What do we need citiesfor?

DO: The size of towns and cities isproportional to the surplus that the countryside is able to produce.This surplus has become gigantic during the period of industrialdevelopment, where one or two percent of the population is able tofeed the rest. In a post-industrial world, where two-thirds of thepopulation is directly involved in growing or gathering food, therewill be many fewer people who will be able to live on agriculturalsurplus. The activities that are typically centralized are those thathave to do with long-range transportation (sail ports) andmanufacturing (mills and manufactures powered by waterwheels). Somecenters of learning may also remain, although much of contemporaryhigher education, which involves training young people foroccupations which will no longer exist, is sure to fall by thewayside.

TB: Some Americans view peak oil andcollapse as another investment opportunity. You already wrote on thefallacies of the faith in money. That leaves a more useful question:what can people do of their savings during or preferably beforecollapse? What can you buy that is truly useful? I assume the answervary greatly according to how much money you still have.

DO: This is a very important question.While there is still time, money should be converted to commodityitems that will remain useful even after the industrial basedisappears. These commodities can be stockpiled in containers and aresure to lose their value more slowly than any paper asset. Oneexample is hand implements for performing manual labor, to provideessential services that are currently performed by mechanized labor.Another is materials that will be needed to bring back essentialpost-industrial services such as sail-based transportation: materialssuch as synthetic fibre rope and sail cloth need to be stockpiledbeforehand to ease the transition.

TB: You don't mention arable land orhousing. Do you think some kind of real property may turn out avaluable post-collapse asset, assuming you can afford them withoutdrowning into debt, or is it too much financial and fiscal liabilityin our pre-collapse era to be of any use?

DO: The laws and customs that governreal property are not helpful or conducive to the right kind ofchange. As the age of mechanized agriculture comes to an end, weshould expect there to be large tracts of fallow land. It won'tmatter too much who owns them, on paper, since the owner is unlikelyto be able to make productive use of large fields without mechanizedlabor. Other patterns of occupying the landscape will have to emerge,of necessity, such as small plots tended by families, forsubsistence. Absentee landlords (those who hold title to land withoutactually physically residing on it but using it as a financial asset)are likely to be simply run off once the financial and mechanicalamplifiers of their feeble physical energies are no longer availableto them. I expect several decades more of fruitless efforts to growcash crops on increasingly depleted land using increasinglyunaffordable and unreliable mechanical and chemical farmingtechniques. These efforts will increasingly lead to failure due toclimate disruption, causing food prices to spike and robbing thepopulation of their savings in a downward spiral. The new patterns ofsubsisting off the land will take time to emerge, but this processcan be accelerated by people who pool resources, buy up, lease, orsimply occupy small tracts of land, and practice permaculturetechniques. Community gardens, guerilla gardening efforts, plantingwild edibles using seed balls, seasonal camps for growing andgathering food, and other humble and low-key arrangements can pavethe way towards something bigger, allowing some groups of people toavoid the most dismal scenario.

TB: How can people make preparationsfor collapse or decline without losing connections with their currentsocial environment, friends, relatives, jobs or customers, andeverything around them that still function as usual. That is aquestion about sanity as much as practicality.

DO: This is perhaps the most difficultquestion. The level of alienation in developed industrial societies,in Europe, North America and elsewhere, is quite staggering. Peopleare only able to form lasting friendships in school, and are unableto become close with people thereafter with the possible exception ofromantic involvements, which are often fleeting. By a certain agepeople become set in their ways, develop manners specific to theirclass, and their interactions with others become scripted and limitedto socially sanctioned, commercial modes. A far-reaching,fundamental transition, such as the one we are discussing, isimpossible without the ability to improvise, to be flexible—ineffect, to be able to abandon who you have been and to change who youare in favor of what the moment demands. Paradoxically, it is usuallythe young and the old, who have nothing to lose, who do the best, andit is the successful, productive people between 30 and 60 who do theworst. It takes a certain detachment from all that is abstract andimpersonal, and a personal approach to everyone around you, tonavigate the new landscape.

I came upon Dmitry Orlov's writings—as with most good things onthe Internet—by letting chance and curiosity guide me from link tolink. It was one of those moments of clarity when a large number ofconfusing questions find their answer along with their correctformulation. For example, the existence of fundamental similaritiesbetween the Soviet Union and the United States was for me a vagueintuition, but I was unable to draw up a detailed list as Dmitry hasdone. One must have lived in two crumbling empires in order to beable to do that.

I must say that my enthusiasm was not sharedby those around me, with whom I have shared my translations. It'sonly natural: who wants to hear how our world of material comfort,opportunity and unstoppable individual progress is about to collapseunder the weight of its own expansion? Certainly not the post-wargeneration high on exuberant growth of the postwar boom (1945-1973),well established in their lives of average consumers since the 1980s,and willing to enjoy a hedonistic age by remaining convinced thatdespite the economic tragedies ravaging society around them, theiryoung children will benefit from more or less the same well-padded,industrialized lifestyle. The generation of children is morereceptive to the notion of economic decline—though to varyingdegrees, depending on the decrease of their purchasing power andlevel of depression in their field of employment (if they have one).

It would be wrong to shoot the messenger who brings badnews. If you read Dmitry carefully, scrupulously separating thefactual bad news, which are beyond his control, from his views onwhat can be done to survive and live in a post-industrial world, youwill find evidence of strong optimism. I hope that in this he isright.

Whatever our views on peak oil and its consequences—orour appetite for scary prophecies—we can find in Dmitry Orlov freshideas on how to conduct our lives in a degraded economic andpolitical environment, reasons to seek unlikely yet fruitfulrelations with our fellow men, or the most effective approach to thefrustrating political and media chatter and the honeyed whisper ofcommercial propaganda (shrug, turn around and go on with your life).

Tancrède Bastié

TB: What difference do you seebetween American and European close future?

DO: European countries are historicalentities that still hold vestiges of allegiances beyond themonetized, corporate realm, while the United States was started as acorporate entity, based on a revolution that was essentially a taxrevolt and thus has no fall-back. The European population is lesstransient than in America, with a stronger sense of regionalbelonging and are more likely to be acquainted with their neighborsand to be able to find a common language and to find solutions tocommon problems.

Probably the largest difference, andthe one most promising for fruitful discussion, is in the area oflocal politics. European political life may be damaged by moneypolitics and free market liberalism, but unlike in the United States,it does not seem completely brain-dead. At least I hope that it isn'tcompletely dead; the warm air coming out of Brussels is oftenindistinguishable from the vapor vented by Washington, but betterthings might happen on the local level. In Europe there is somethingof a political spectrum left, dissent is not entirely futile, andrevolt is not entirely suicidal. In all, the European politicallandscape may offer many more possibilities for relocalization, fordemonitization of human relationships, for devolution to more localinstitutions and support systems, than the United States.

TB: Will American collapse delayEuropean collapse or accelerate it?

DO: There are many uncertainties to howevents might unfold, but Europe is at least twice as able to weatherthe next, predicted oil shock as the United States. Once petroleumdemand in the US collapses following a hard crash, Europe will for atime, perhaps for as long as a decade, have the petroleum resourcesit needs, before resource depletion catches up with demand.

The relative proximity to Eurasia'slarge natural gas reserves should also prove to be a major safeguardagainst disruption, in spite of toxic pipeline politics. Thepredicted sudden demise of the US dollar will no doubt beeconomically disruptive, but in the slightly longer term the collapseof the dollar system will stop the hemorrhaging of the world'ssavings into American risky debt and unaffordable consumption. Thisshould boost the fortunes of Eurozone countries and also give somebreathing space to the world's poorer countries.

TB: How does Europe compare to theUnited States and the former Soviet Union, collapse-wise?

DO: Europe is ahead of the UnitedStates in all the key Collapse Gap categories, such as housing,transportation, food, medicine, education and security. In all theseareas, there is at least some system of public support and someelements of local resilience. How the subjective experience ofcollapse will compare to what happened in the Soviet Union issomething we will all have to think about after the fact. One majordifference is that the collapse of the USSR was followed by a wave ofcorrupt and even criminal privatization and economic liberalization,which was like having an earthquake followed by arson, whereas I donot see any horrible new economic system on the horizon that is readyto be imposed on Europe the moment it stumbles. On the other hand,the remnants of socialism that were so helpful after the Sovietcollapse are far more eroded in Europe thanks to the recent wave offailed experiments of market liberalization.

TB: How does peak oil interact withpeak gas and peak coal? Should we care about other peaks?

DO: The various fossil fuels are notinterchangeable. Oil provides the vast majority of transport fuels,without which commerce in developed economies comes to a standstill.Coal is important for providing for the base electric load in manycountries (not France, which relies on nuclear). Natural gas(methane) provides ammonia fertilizer for industrial agriculture, andalso provides thermal energy for domestic heating, cooking andnumerous manufacturing processes.

All of these supplies are past theirpeaks in most countries, and are either past or approaching theirpeaks globally.

About a quarter of all the oil is stillbeing produced from a handful of super-giant oil fields which werediscovered several decades ago. The productive lives of these fieldshave been extended by techniques such as in-fill drilling and waterinjection. These techniques allow the resource to be depleted morefully and more quickly, resulting in a much steeper decline: the oilturns to water, slowly at first, then all at once. The super-giantCantarell field in the Gulf of Mexico is a good example of such rapiddepletion, and Mexico does not have many years left as an oilexporter. Saudi Arabia, the world's second-largest oil producer afterRussia, is very secretive about its fields, but it is telltale thatthey have curtailed oil field development and are investing in solartechnology.

Although there is currently an attemptto represent as a break-through the new (in reality, not so new) hydraulic fracturingand horizontal drilling techniques for producing natural gas fromgeological formations, such as shale, that were previously consideredinsufficiently porous, this is, in reality, a financial play. Theeffort is too expensive in terms of both technical requirements andenvironmental damage to pay for itself, unless the price of naturalgas rises to the point where it starts to cause economic damage,which suppresses demand.

Coal was previously thought to be veryabundant, with hundreds of years of supply left at current levels.However, these estimates have been reassessed in recent years, and itwould appear that the world's largest coal producer, China, is quiteclose to its peak. Since it is coal that has directly fueled therecent bout of Chinese economic growth, this implies that Chineseeconomic growth is at an end, with severe economic, social andpolitical dislocations to follow. The US relies on coal for close tohalf of its electricity generation, and is likewise unable toincrease the use of this resource. Most of the energy-denseanthracite has been depleted in the US, and what is being producednow, through environmentally destructive techniques such asmountaintop removal, is much lower grades of coal. The coal is slowlyturning to dirt. At a certain point in time coal will cease toprovide an energy gain: digging it up, crushing it and transportingit to a power plant will become a net waste of energy.

It is essential to appreciate the factthat it is oil, and the transport fuels produced from it, thatenables all other types of economic activity. Without diesel forlocomotives, coal cannot be transported to power plants, the electricgrid goes down, and all economic activity stops. It is also essentialto understand that even minor shortfalls in the availability oftransport fuels have severe economic knock-on effects. These effectsare exacerbated by the fact that it is economic growth, not economicdécroissance [Fr., "de-growth"] (which seems inevitable, given the factors describedabove) that forms the basis of all economic and industrial planning.Modern industrial economies, at the financial, political andtechnological level, are not designed for shrinkage, or even forsteady state. Thus, a minor oil crisis (such as the recent steadyincrease in the price of oil punctuated by severe price spikes)results in a sociopolitical calamity.

Lastly, it bears mentioning that fossilfuels are really only useful in the context of an industrial economythat can make use of them. An industrial economy that is in anadvanced state of decay and collapse can neither produce nor make useof the vast quantities of fossil fuels that are currently burned updaily. There is no known method of scaling industry down to boutiquesize, to serve just the needs of the elite, or to provide lifesupport to social, financial and political institutions thatco-evolved with industry in absence of industry. It also bearspointing out that fossil fuel use was very tightly correlated withhuman population size on the way up, and is likely to remain so onthe way down. Thus, it may not be necessary to look too far past thepeak in global oil production to see major disruption of globalindustry, which will make other fossil fuels irrelevant.

TB: How is post-collapse Russiadoing ? Ready for its second peak ?

DO: Russia remains the world's largestoil producer. Although it has been unable to grow its conventionaloil production, it has recently claimed that it can double its oilendowment by drilling offshore in the melting Arctic. Russia is andremains Europe's second largest energy asset. In spite of toxicpipeline politics (which have recently been remedied somewhat by theconstruction of the Nordstream gas pipeline across the Baltic) it hashistorically been the single most reliable European energy supplier,and shows every intention of remaining so into the future.

TB: Is there hope for a safe,harmless European decline, or is any industrial society just bound tocollapse at once when fuel runs out?

DO: The severity of collapse willdepend on how quickly societies can scale down their energy use,curtail their reliance on industry, grow their own food, go back tomanual methods of production for fulfilling their immediate needs,and so forth. It is to be expected that large cities and industrialcenters will depopulate the fastest. On the other hand, remote,land-locked, rural areas will not have the local resources to rebootinto a post-industrial mode. But there is hope for small-to-middlingtowns that are surrounded by arable land and have access to awaterway. To see what will be survivable, one needs to look atancient and medieval settlement patterns, ignoring places that becameoverdeveloped during the industrial era. Those are the places to moveto, to ride out the coming events.

TB: I remember my grandmothertelling me about the German occupation, when urban and suburbandwellers flocked into country towns every Sunday with empty cases,eager too find some food to buy from the local farmers, hoping backin a train the same day. Is there any advantage in living in a city,in a post-collapse era, rather than in the countryside?

DO: Surviving in the countrysiderequires a different mindset, and different set of skills thansurviving in a town or a city. Certainly, most of our contemporaries,who spend their days manipulating symbols, and expect to be fed fordoing so, would not survive when left to their own devices in thecountryside. On the other hand, even those living in the countrysideare currently missing much of the know-how they once had forsurviving without industrial supplies, and lack the resources toreconstitute it in a crisis. There could be some fruitfulcollaboration between them, given sufficient focus and preparation.

TB: Can we grow sufficient food withlow technology, low energy methods, out of highly exhausted, highlypolluted farmland ? It seems we might end up in a worse farmingsituation than our ancestors just two or three generations ago.

DO: That is certainly true. Add globalwarming, which is already causing severe soil erosion due totorrential rains and floods, droughts and heat waves in other areas.It is likely that agriculture as it has existed for the past tenthousand years will become ineffective in many areas. However, thereare other techniques for growing food, which involve setting upstable ecosystems consisting of many species of plants and animals,including humans, living together synergistically. What will ofnecessity be left behind is the current system, where fertilizers andpesticides are spread out on tilled dirt (rather than living soil) tokill everything but one organism (a cash crop) which is thenmechanically harvested, processed, ingested, excreted, and flushedinto the ocean. This system is already encountering a hard limit inthe availability of phosphate fertilizer. But it is possible tocreate closed cycle systems, where nutrients stay on the land and areallowed to build up over time. The key to post-industrial humansurvival, it turns out, is in making proper use of human excrementand urine.

TB: If cities or big towns survivecollapse, what will be their core activities? What do we need citiesfor?

DO: The size of towns and cities isproportional to the surplus that the countryside is able to produce.This surplus has become gigantic during the period of industrialdevelopment, where one or two percent of the population is able tofeed the rest. In a post-industrial world, where two-thirds of thepopulation is directly involved in growing or gathering food, therewill be many fewer people who will be able to live on agriculturalsurplus. The activities that are typically centralized are those thathave to do with long-range transportation (sail ports) andmanufacturing (mills and manufactures powered by waterwheels). Somecenters of learning may also remain, although much of contemporaryhigher education, which involves training young people foroccupations which will no longer exist, is sure to fall by thewayside.

TB: Some Americans view peak oil andcollapse as another investment opportunity. You already wrote on thefallacies of the faith in money. That leaves a more useful question:what can people do of their savings during or preferably beforecollapse? What can you buy that is truly useful? I assume the answervary greatly according to how much money you still have.

DO: This is a very important question.While there is still time, money should be converted to commodityitems that will remain useful even after the industrial basedisappears. These commodities can be stockpiled in containers and aresure to lose their value more slowly than any paper asset. Oneexample is hand implements for performing manual labor, to provideessential services that are currently performed by mechanized labor.Another is materials that will be needed to bring back essentialpost-industrial services such as sail-based transportation: materialssuch as synthetic fibre rope and sail cloth need to be stockpiledbeforehand to ease the transition.

TB: You don't mention arable land orhousing. Do you think some kind of real property may turn out avaluable post-collapse asset, assuming you can afford them withoutdrowning into debt, or is it too much financial and fiscal liabilityin our pre-collapse era to be of any use?

DO: The laws and customs that governreal property are not helpful or conducive to the right kind ofchange. As the age of mechanized agriculture comes to an end, weshould expect there to be large tracts of fallow land. It won'tmatter too much who owns them, on paper, since the owner is unlikelyto be able to make productive use of large fields without mechanizedlabor. Other patterns of occupying the landscape will have to emerge,of necessity, such as small plots tended by families, forsubsistence. Absentee landlords (those who hold title to land withoutactually physically residing on it but using it as a financial asset)are likely to be simply run off once the financial and mechanicalamplifiers of their feeble physical energies are no longer availableto them. I expect several decades more of fruitless efforts to growcash crops on increasingly depleted land using increasinglyunaffordable and unreliable mechanical and chemical farmingtechniques. These efforts will increasingly lead to failure due toclimate disruption, causing food prices to spike and robbing thepopulation of their savings in a downward spiral. The new patterns ofsubsisting off the land will take time to emerge, but this processcan be accelerated by people who pool resources, buy up, lease, orsimply occupy small tracts of land, and practice permaculturetechniques. Community gardens, guerilla gardening efforts, plantingwild edibles using seed balls, seasonal camps for growing andgathering food, and other humble and low-key arrangements can pavethe way towards something bigger, allowing some groups of people toavoid the most dismal scenario.

TB: How can people make preparationsfor collapse or decline without losing connections with their currentsocial environment, friends, relatives, jobs or customers, andeverything around them that still function as usual. That is aquestion about sanity as much as practicality.

DO: This is perhaps the most difficultquestion. The level of alienation in developed industrial societies,in Europe, North America and elsewhere, is quite staggering. Peopleare only able to form lasting friendships in school, and are unableto become close with people thereafter with the possible exception ofromantic involvements, which are often fleeting. By a certain agepeople become set in their ways, develop manners specific to theirclass, and their interactions with others become scripted and limitedto socially sanctioned, commercial modes. A far-reaching,fundamental transition, such as the one we are discussing, isimpossible without the ability to improvise, to be flexible—ineffect, to be able to abandon who you have been and to change who youare in favor of what the moment demands. Paradoxically, it is usuallythe young and the old, who have nothing to lose, who do the best, andit is the successful, productive people between 30 and 60 who do theworst. It takes a certain detachment from all that is abstract andimpersonal, and a personal approach to everyone around you, tonavigate the new landscape.

Published on December 15, 2011 18:57

December 12, 2011

Grinch season

[image error]

[image error] One of these men stole an election, the other over a billion dollars. Or is it the other way around? Among their many similarities, one stands out: they both seem to be getting away with it. They must both be magicians! (One of them is now a meme. And so is the other.)

[image error] One of these men stole an election, the other over a billion dollars. Or is it the other way around? Among their many similarities, one stands out: they both seem to be getting away with it. They must both be magicians! (One of them is now a meme. And so is the other.)

Published on December 12, 2011 16:48

December 8, 2011

Party of Swindlers and Thieves

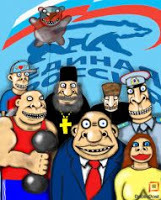

Russia has recently held parliamentary elections, which were, by most accounts, riddled with fraud. In the aftermath of the election, protests have erupted in Moscow, St. Petersburg and other parts of Russia. In the run-up to the elections, Putin's United Russia party was characterized as "Party of Swindlers and Thieves," known for phenomenal levels of corruption and for enshrining a new, untouchable bureaucratic aristocracy, bloated on siphoned-off oil and gas revenues, who refer to the commonplace bribes as "gratitude." In polling prior to the election, United Russia was garnering only some 15% of the vote, behind both the Communists and the Liberal Democrats. But thanks to rampant ballot stuffing, vote miscounting and other types of forgery, often carried out quite openly, it came in with a majority. The number of votes for United Russia was roughly doubled. Now it seems that the fraudulent tallies will be disputed in the courts. The word "revolution" is being bandied about only half-jokingly.

Russia has recently held parliamentary elections, which were, by most accounts, riddled with fraud. In the aftermath of the election, protests have erupted in Moscow, St. Petersburg and other parts of Russia. In the run-up to the elections, Putin's United Russia party was characterized as "Party of Swindlers and Thieves," known for phenomenal levels of corruption and for enshrining a new, untouchable bureaucratic aristocracy, bloated on siphoned-off oil and gas revenues, who refer to the commonplace bribes as "gratitude." In polling prior to the election, United Russia was garnering only some 15% of the vote, behind both the Communists and the Liberal Democrats. But thanks to rampant ballot stuffing, vote miscounting and other types of forgery, often carried out quite openly, it came in with a majority. The number of votes for United Russia was roughly doubled. Now it seems that the fraudulent tallies will be disputed in the courts. The word "revolution" is being bandied about only half-jokingly. United RussiaPublic disillusionment with Putin was already quite profound before the elections, but the ensuing protests are something new in Russia's recent political experience: people who were not likely to protest up until this point have decided to turn up. Many of them have clearly decided that enough is enough. But I feel that they are being misread, both in Russia and in the West. In Russia, commentators from the official media are eager to paint them orange: they are stooges propped up by operatives and money from the US State Department, which wants to strip Russia of its sovereignty and turn it into another Libya. Western commentators, meanwhile, seem to believe that Russia is, variously, about to revert into the USSR, or to go through another revolution. All of this is pretty much nonsense. Whether their demand is voiced in exactly these terms or not, what will make these protesters go home, and then peacefully show up and vote the next time, is full and immediate enforcement of Chapter 141 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation: "Obstruction of voting rights or work of election commissions: ...punishable by a fine from 200 to 500... [minimum monthly] wages... or correctional labor for a term of one year to two years, or imprisonment for up to six months, or imprisonment for a term not exceeding five years." The operatives in the field would get a stiff fine, the middle-managers of this election fraud extravaganza would get to cool their heels, and the masterminds and orchestrators of the fraud would get five years in the slammer. This would placate the electorate, and also make a replay highly unlikely.

United RussiaPublic disillusionment with Putin was already quite profound before the elections, but the ensuing protests are something new in Russia's recent political experience: people who were not likely to protest up until this point have decided to turn up. Many of them have clearly decided that enough is enough. But I feel that they are being misread, both in Russia and in the West. In Russia, commentators from the official media are eager to paint them orange: they are stooges propped up by operatives and money from the US State Department, which wants to strip Russia of its sovereignty and turn it into another Libya. Western commentators, meanwhile, seem to believe that Russia is, variously, about to revert into the USSR, or to go through another revolution. All of this is pretty much nonsense. Whether their demand is voiced in exactly these terms or not, what will make these protesters go home, and then peacefully show up and vote the next time, is full and immediate enforcement of Chapter 141 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation: "Obstruction of voting rights or work of election commissions: ...punishable by a fine from 200 to 500... [minimum monthly] wages... or correctional labor for a term of one year to two years, or imprisonment for up to six months, or imprisonment for a term not exceeding five years." The operatives in the field would get a stiff fine, the middle-managers of this election fraud extravaganza would get to cool their heels, and the masterminds and orchestrators of the fraud would get five years in the slammer. This would placate the electorate, and also make a replay highly unlikely. The CommunistsBut just how far gone is Putin's government? The evidence so far is that they are still feeling invincible, and are willing to resort to repression in order to make the election results stick. But the Russian people want to express themselves; they want to be heard; they want those who hear them to make the required changes in response. Immediately after the election Medvedev was quick to start talking about coalition-building, but then the inertia of the party apparatus took over. Everybody wants to keep their seat, votes be damned. And now arrests are being made, troop carriers are rolling in and helicopters are circling overhead: these are not the right moves for opening a dialog and offering to make amends. Tomorrow, 10 of December, is likely to see large demonstrations. Perhaps it will turn out to be a date for the history books. Or perhaps the government will come to their senses in time, and start clawing back the legitimacy they have so foolishly squandered.

The CommunistsBut just how far gone is Putin's government? The evidence so far is that they are still feeling invincible, and are willing to resort to repression in order to make the election results stick. But the Russian people want to express themselves; they want to be heard; they want those who hear them to make the required changes in response. Immediately after the election Medvedev was quick to start talking about coalition-building, but then the inertia of the party apparatus took over. Everybody wants to keep their seat, votes be damned. And now arrests are being made, troop carriers are rolling in and helicopters are circling overhead: these are not the right moves for opening a dialog and offering to make amends. Tomorrow, 10 of December, is likely to see large demonstrations. Perhaps it will turn out to be a date for the history books. Or perhaps the government will come to their senses in time, and start clawing back the legitimacy they have so foolishly squandered. Liberal DemocratsIf they fail to do so, they would be setting the stage for, if not a revolution, then at least a rebellion. The outraged but well-meaning and peaceful crowds of protesters of today would, over a period of months or years, morph into a surly, implacable, vicious mob ready to drown the government in their own blood. In due course, their instinct for self-preservation will become suppressed, as other, opportunistic, idealistic or heroic motivations move to the forefront. The progression is the same everywhere: first the people ask, then they demand, then they come and they take. For now, talk of revolution is restricted to those, both in the West and in Russia, who use it to justify their budgets for fermenting or suppressing revolt, respectively. They are, in both cases, a waste of public money.

Liberal DemocratsIf they fail to do so, they would be setting the stage for, if not a revolution, then at least a rebellion. The outraged but well-meaning and peaceful crowds of protesters of today would, over a period of months or years, morph into a surly, implacable, vicious mob ready to drown the government in their own blood. In due course, their instinct for self-preservation will become suppressed, as other, opportunistic, idealistic or heroic motivations move to the forefront. The progression is the same everywhere: first the people ask, then they demand, then they come and they take. For now, talk of revolution is restricted to those, both in the West and in Russia, who use it to justify their budgets for fermenting or suppressing revolt, respectively. They are, in both cases, a waste of public money. The Future is Ours!But if this dynamic were allowed to develop, then much more would be lost. Under Putin, Russia has become more stable and more prosperous. The cities have become more vibrant, and life has become better for many people, not just the ones at the very top. In striking contrast to the USA or the European Union, Russia is solvent rather than bankrupt. Putin gets the credit for these achievements. The slogan of his "United Russia"—"The future is ours"—is overweening and pompous (and, inadvertently, reminiscent of the Third Reich!) but, in some part thanks to his efforts, Russia does have a discernible future in a way that the US and the EU do not.

The Future is Ours!But if this dynamic were allowed to develop, then much more would be lost. Under Putin, Russia has become more stable and more prosperous. The cities have become more vibrant, and life has become better for many people, not just the ones at the very top. In striking contrast to the USA or the European Union, Russia is solvent rather than bankrupt. Putin gets the credit for these achievements. The slogan of his "United Russia"—"The future is ours"—is overweening and pompous (and, inadvertently, reminiscent of the Third Reich!) but, in some part thanks to his efforts, Russia does have a discernible future in a way that the US and the EU do not. The Future is... Oops!Given that this is the case, one would expect the more thoughtful people in the US and in Europe to simply stand back and watch, hoping to learn something. Yet mindsets are slow to change, and some of them are still operating with their illusions of imperial power intact. Some of them are seeing orange, and thinking that there might be an opening to smuggle a neocon like Gary Kasparov into the Kremlin. But to a great many Russians their ruse of promoting "freedom and democracy" is already transparent: what they want to do is to destroy Russia's sovereignty. They almost succeeded in destroying it in the 1990s; they won't get that chance again. Now is not their time to try to influence Russian politics; now is their time to shrivel up.

The Future is... Oops!Given that this is the case, one would expect the more thoughtful people in the US and in Europe to simply stand back and watch, hoping to learn something. Yet mindsets are slow to change, and some of them are still operating with their illusions of imperial power intact. Some of them are seeing orange, and thinking that there might be an opening to smuggle a neocon like Gary Kasparov into the Kremlin. But to a great many Russians their ruse of promoting "freedom and democracy" is already transparent: what they want to do is to destroy Russia's sovereignty. They almost succeeded in destroying it in the 1990s; they won't get that chance again. Now is not their time to try to influence Russian politics; now is their time to shrivel up.

Published on December 08, 2011 04:00

December 2, 2011

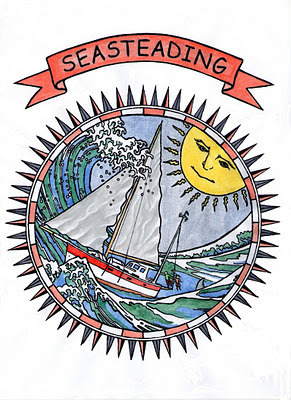

Seasteading!

Many thanks to Mark, who turned my clumsy sketch into a real piece of art. If you would like to own a t-shirt with this on it, please vote over on the right, because I need to know how many of which size to order. I'll place the order once the voting is done.

Yes, that's our boat, and yes, that's me and my wife hanging off the mizzen mast, and yes, that's a shark's fin in the water behind us. See if you can find the cat.

Yes, that's our boat, and yes, that's me and my wife hanging off the mizzen mast, and yes, that's a shark's fin in the water behind us. See if you can find the cat.

(For the strange people who believe "Seasteading" implies building private artificial islands for rich people to hide out on, and who might also think I am infringing on their trademark: in my case it is about selling t-shirts that happen to say "Seasteading" on them. We are in different industries, see?)

Yes, that's our boat, and yes, that's me and my wife hanging off the mizzen mast, and yes, that's a shark's fin in the water behind us. See if you can find the cat.

Yes, that's our boat, and yes, that's me and my wife hanging off the mizzen mast, and yes, that's a shark's fin in the water behind us. See if you can find the cat. (For the strange people who believe "Seasteading" implies building private artificial islands for rich people to hide out on, and who might also think I am infringing on their trademark: in my case it is about selling t-shirts that happen to say "Seasteading" on them. We are in different industries, see?)

Published on December 02, 2011 22:16

Occupy the Million Dollar View

Now that the current phase of the Occupation movement—one that involved camping out in public places—is drawing to a close, thoughts turn to other, even more effective venues and exploits. Occupying the front lawns of mansions owned by the 1% would certainly send a message, although a very brief one, since trespassing happens to be illegal.

Now that the current phase of the Occupation movement—one that involved camping out in public places—is drawing to a close, thoughts turn to other, even more effective venues and exploits. Occupying the front lawns of mansions owned by the 1% would certainly send a message, although a very brief one, since trespassing happens to be illegal. And then it hit me: it just so happens that the 1% own, roughly speaking, 99% of the really desirable beachfront properties, while the 99% have to make do with the 1% or so of the coastline that is reserved for public use. The 1%ers really like that "million-dollar view," and the seaside mansion is one of their ultimate status symbols. Try to approach them from land, and you will quickly get spotted by vigilant local police and private security and won't make it very far—well shy of making any sort of statement, or even getting on the 1%er's radar.

But it just so happens that, according to US Federal law, they can only own property down to the low water line. In absence of specific regulations (marine sanctuary, public beach, municipal harbor, shipping lane, military reservation and so on) everything below the low water line is considered public anchorage. (It is everything below the high water line in Canada, which means that you can even occupy the beach at low tide and still not be trespassing.) Any vessel can anchor within a few meters of the 1%ers property, entirely spoiling their precious view, but if the boat is manned and is legal, then there is not a thing that they can do about it. On a calm evening, you can sail up, anchor, raft up, put up a big screen to use as a sail, and project a movie onto it. Eat the Rich, anyone? Then film their reaction, and project that next.

You might think that getting a sailboat flotilla together takes a lot of money. The boats that 1%ers such as Senator John Kerry prefer certainly are super-pricy, but then there are also many boats that can be had for free or for $1 (provided you agree to sail it away), or for a very small sum. If a sailboat is engineless or has an outboard engine of 9.9 horsepower or less (which doesn't count as a real engine) then it is automatically grandfathered in and doesn't even need to be registered: just paint a name and a port of call on the transom, and it is legal. Would you like a more permanent occupation? Rotate vessels through the anchorage, going on an overnight cruise to nowhere every fortnight or so, keep all of the boats occupied at all times, and you are still legal.