Dmitry Orlov's Blog, page 31

September 21, 2011

September 11, 2011

ASPO Conference

I'll be speaking at the ASPO in Washington, DC on November 2-5 on why gradual energy descent is a science-fiction scenario that includes friendly oil-exporting space aliens and why the end of the fossil fuel age is likely to be a step-function. I will also talk about investing for post-collapse. I believe that there might still be time to engineer a soft landing at the end of the upcoming economic cliff-diving exercise. This can be done if groups of individuals decide to sell off financial instruments that will have little or no survival value post-collapse (stocks, bonds, gold, etc.) and invest in something that is not useful now but will be post-collapse: complete construction kits for businesses to deliver products and services that are certain to be in high demand post-collapse, for lack of better alternatives. To make this scenario possible, it is necessary to design plans, recruit people and stockpile and pre-position materials while finance, industry and transportation systems are still functioning. I hope to see some of you there.

I'll be speaking at the ASPO in Washington, DC on November 2-5 on why gradual energy descent is a science-fiction scenario that includes friendly oil-exporting space aliens and why the end of the fossil fuel age is likely to be a step-function. I will also talk about investing for post-collapse. I believe that there might still be time to engineer a soft landing at the end of the upcoming economic cliff-diving exercise. This can be done if groups of individuals decide to sell off financial instruments that will have little or no survival value post-collapse (stocks, bonds, gold, etc.) and invest in something that is not useful now but will be post-collapse: complete construction kits for businesses to deliver products and services that are certain to be in high demand post-collapse, for lack of better alternatives. To make this scenario possible, it is necessary to design plans, recruit people and stockpile and pre-position materials while finance, industry and transportation systems are still functioning. I hope to see some of you there.

Published on September 11, 2011 08:07

September 10, 2011

How I Survived Hurricane Irene

Quite a few well-meaning people have written to ask me how I survived the recent hurricane. Some have even suggested that I should give up living aboard and flee to higher ground.

Quite a few well-meaning people have written to ask me how I survived the recent hurricane. Some have even suggested that I should give up living aboard and flee to higher ground.We spent the entire event at the dock, bobbing up and down slightly and leaning over a bit in the wind gusts. By the time she hit Boston Harbor, Irene was downgraded to a tropical storm, with the eye well to the west of us. Still, we got buckets of rain and several hours of gale winds.

The worst of it was the preparation. I had to clear lots of things off the docks and the deck, rig additional dock lines, lace up the sail cover so it wouldn't flog in the wind, take down the awning, secure the dink so that it wouldn't get bashed around, tie down various items on deck so that they wouldn't blow away, fill the water tanks for additional ballast and in case we lost shore water, and so forth. That seemed like a lot of work.

During the hurricane itself we stayed on board, where it was warm and dry. We rocked a bit, and we spent a few hours leaning at about a 15º angle in the stiff breeze. My wife and the cat pretty much slept through the entire event. I would venture out periodically, mill around on the docks with the neighbors, adjust a few dock lines, and go back inside.

A few worst case scenarios were being contemplated, without much conviction, because several people have seen much worse. In one scenario the docks themselves start breaking up and boats start bashing into each other. As it turned out, just one dock cleat pulled out and some boards popped out of the finger piers from the twisting. Another potential problem would be if wind gusts got so stiff that sailboat masts would get tangled up in each others' rigging, possibly leading to a few dismastings. They didn't even get close. The ultimate nightmare scenario involved a storm surge so huge that the entire structure would float off the pilings and crash into the seawall. We were well short of that, in spite of a couple of extra high tides due to the full moon that coincided with the storm surge. We never even lost shore electricity, shore water or internet access, but with a wind generator, 1000 liters of water and plenty of books this wouldn't have affected us too much either.

During the worst of it

During the worst of itIt seems like our "house" was designed to take it better than your average house. In a hurricane, there is a high risk of flooding, so it is helpful if your house can float. Also, there is a high risk of very high winds, so the house should be streamlined in shape and able to withstand hurricane force winds, even while floating. The combination of water and wind is known to cause waves, so it is helpful if the house can take the ocean swell and the odd breaking wave without capsizing or swamping. There is a good chance of power cuts and water main and gas line breaks, so the house should have its own internal electricity generation system, and its own supplies of water and propane. Lastly, a hurricane might make a certain area uninhabitable for a period of time, prompting you to want to move, but hurricanes also tend to wash away roads and bridges, so it would be better if your house could make its escape via the waterways. There might also be fuel supply disruptions, so it's better if your house can move without the use of fossil fuels by, say, hoisting a sail or two. In short, if you want to survive a hurricane, you want to be on a sailboat.

Now, granted, you could also be perfectly safe in a house that's built to withstand a hurricane, in an area that's full of such houses. But where is that? Most people I know can't afford the house they are living in now, never mind making it hurricane-proof.

Aside from hurricanes, there are forest fires, tsunamis and earthquakes. Forest fires aren't much of a problem out on the water. Tsunamis are uniquely survivable aboard a boat, given a bit of warning; when you see the water going out, head for deep water. Then, once it's all over, come back to survey the damage. During the recent East Coast earthquake, which damaged the National Cathedral in Washington, everyone in Boston felt it. My wife didn't; she was on the boat at the time.

It was a wet and windy weekend, and I didn't get a lot done. But compared to the scenes of devastation we see among the East Coast communities from Hatteras all the way up the coast and inland through Western Massachusetts to Vermont, for those of us living afloat in the harbor Hurricane Irene was pretty much a non-event.

Published on September 10, 2011 09:10

August 21, 2011

Reinventing Collapse in the US and Canada

by Justin Ritchie,

The Tyee

It's all too easy to make jokes about our neighbors to the south for their dramatic weight problems, generally poor understanding of geography and that stretch of coastline now famously known as the Jersey Shore.

Yet we're seriously reliant on the economic health our southern neighbours. In British Columbia, 45.9 per cent of our total exports went to the U.S. last year. The Canadian economy exports over 70 per cent of its products to the States, forming the world's largest trading relationship between two nations. The case could be made that no other sovereign economy is tied to the U.S. more than Canada's.

So when someone deeply familiar with the collapse of the Soviet Union writes about how the States is headed in the same direction, we might wish to pay attention. Even greater cause for concern is that he has been doing so since 2005, and his predictions have been proving true at alarming accuracy. That, combined with a crushing national debt hovering over Washington D.C., means there is a prescient need for people to hear from those experienced with "superpower collapse."

Dmitry Orlov writes not for fame or fortune, but to provide a book with which you can smack your friends across the head when they state, "No one could have seen this coming." He moved with his family from the USSR to the U.S. as a kid, but his career allowed many opportunities to travel back home and catch glimpses of growing collapse. Though the USSR had been falling apart slowly, it wasn't until Yeltsin uttered the words "Former Soviet Union" that it seemed to happen all at once. The world's first superpower collapsed because its founding myths of technological progress and "bread for all" had failed to match reality.

Moving past the 'iron triangle'

In the newly revised version of Reinventing Collapse, first published in 2008 before the financial crisis began later that year, Orlov expands on his attempt to convince you that the U.S. is much less prepared for collapse than the Soviet Union ever was. Though headlines declaring the end of America won't appear anytime soon, Orlov forecasts that collapse will happen for each person individually, as they are rudely awakened from the American Dream. And while his propositions can be frightening at times, he understands that forecasts of superpower collapse will either frustrate or alienate most people, or end up largely ignored -- until it's too late.

[image error]<a href="http://ad.thetyee.ca/www/delivery/ck...." target="_blank"><img src="http://ad.thetyee.ca/www/delivery/avw..." border="0" alt="" /></a> Many of Orlov's forecasts from the previous edition have proven accurate. Orlov's America is a system barely able to sustain itself, ruined by a population bent on a hardened mythology: an iron triangle of home, car and job that is out of touch with the reality of rapidly depleting cheap energy, which made vehicle ownership and suburban home life a gateway to the goal of being middle class. Orlov predicted that as the steady stream of money from employment dried up, the country's depleted social infrastructure would be exposed and the American standard of living would plummet. His forecasts are lived out by the people who have their home in the underground corridors of Las Vegas and in cars across the nation.

Orlov argues that there is a clear recipe for social unrest in the U.S., with approximately 350 million guns, a consumption rate of two-thirds of the world's anti-depressant drugs and a national homicide rate that could be equaled by a 9-11-sized event every month. The can-do American spirit and career-oriented mindset may have served its residents well in the past, but it will be particularly vulnerable in the transition to a post-growth economy. Contrasted to the Russian work ethic during the latter stage of Soviet decline, Orlov says that someone who worked hard and played hard was considered a fool. American career ethics and economic dynamics have lead to patterns of migration that uproot people from communities, something we're witnessing in Canada now -- though this can be a positive in times of collapse, as it makes us more open to strangers and varied living situations than the tightly knit Russian communities Orlov witnessed. Vancouverites know how difficult affordable housing can be, and openness is an asset as living affordability becomes more precarious.

Orlov contrasts the U.S. and the USSR in areas as diverse as housing policies, health care, food production and core societal myths. His explanation of the difference between Soviet and American expectations for education particularly resonated with me. While Soviet schools had far fewer resources, they produced children that knew much more general information and had better conceptual understanding, rather than a focus on exams. At my university in North Carolina, I experienced that exact dynamic. When a professor made a point to avoid specific outlines of what to study, students squirmed with discomfort. In classes with Russian professors, students complained that exams didn't follow homework problems, testing concepts instead. Orlov concludes this is because schools in the U.S. aren't about learning, they are about institutionalization; merely biding the time while kids enter the institution of the workforce, government, a corporation or prison.

Age of opportunity?

While the updated Reinventing Collapse retains many of its first edition's ideas, it reads smoother and makes the case stronger for the collapse of the U.S. But it's not all doom and gloom. Orlov presents very clear and surprisingly optimistic recommendations, revealing an age of opportunity for those willing to adjust their expectations. Orlov thinks black market economies in scavenged material will become the norm in the near future -- and evidence of that is booming, as witnessed by the rapid growth industry of copper and air conditioner theft in the U.S. Orlov explains that expensive health care will become out of reach for the majority, and alternative medicine will grow in popularity as the complex networks that enable pharmaceuticals wither away. He says that instead of building an electric car no one can afford, products and services can be designed to serve the huge and untapped market segment of the permanently unemployed. There will be a need, he says, for low-cost housing opportunities like dormitories, GPS devices for retrieving and locating stashes of gear, or campgrounds that provide garden plots.

The American economy is deeply tied to oil consumption at incredible levels, made possible by the world's reserve currency. Orlov explains that as oil prices increase, the economy will decline, leading to shortages of serviceable equipment and an inability for citizens to consume -- hurting economic activity further, weakening the U.S. dollar and making more oil even further out of reach. Once shortages appear, much of the spare gasoline is wasted idling at the few gas stations still open and hoarded by those with ambition and foresight. Reinventing Collapse explains how even a relatively minor temporary disruption in gasoline could lead to a dramatic shift to a black market economy for fueling vehicles. Another advantage lies herein for Canada as the value of the loonie has been closely tied to oil prices for over a decade.

So where does that leave Canada? While our debt-to-GDP ratio is among the healthiest of the G20, economic ties to the U.S. means we should pay attention. By understanding where the U.S. is headed, perhaps the argument for greater resilience and sustainability here in Canada can be made anew.

Justin Ritchie counts himself among the first refugees from the U.S. to Canada. He covers sustainability and sociological issues as co-host of the Extraenvironmentalist podcast at http://extraenvironmentalist.com. He is the sustainability coordinator for the UBC Alma Mater Society and is working on energy materials as a Master's of Materials Engineering student at the University of British Columbia.

It's all too easy to make jokes about our neighbors to the south for their dramatic weight problems, generally poor understanding of geography and that stretch of coastline now famously known as the Jersey Shore.

Yet we're seriously reliant on the economic health our southern neighbours. In British Columbia, 45.9 per cent of our total exports went to the U.S. last year. The Canadian economy exports over 70 per cent of its products to the States, forming the world's largest trading relationship between two nations. The case could be made that no other sovereign economy is tied to the U.S. more than Canada's.

So when someone deeply familiar with the collapse of the Soviet Union writes about how the States is headed in the same direction, we might wish to pay attention. Even greater cause for concern is that he has been doing so since 2005, and his predictions have been proving true at alarming accuracy. That, combined with a crushing national debt hovering over Washington D.C., means there is a prescient need for people to hear from those experienced with "superpower collapse."

Dmitry Orlov writes not for fame or fortune, but to provide a book with which you can smack your friends across the head when they state, "No one could have seen this coming." He moved with his family from the USSR to the U.S. as a kid, but his career allowed many opportunities to travel back home and catch glimpses of growing collapse. Though the USSR had been falling apart slowly, it wasn't until Yeltsin uttered the words "Former Soviet Union" that it seemed to happen all at once. The world's first superpower collapsed because its founding myths of technological progress and "bread for all" had failed to match reality.

Moving past the 'iron triangle'

In the newly revised version of Reinventing Collapse, first published in 2008 before the financial crisis began later that year, Orlov expands on his attempt to convince you that the U.S. is much less prepared for collapse than the Soviet Union ever was. Though headlines declaring the end of America won't appear anytime soon, Orlov forecasts that collapse will happen for each person individually, as they are rudely awakened from the American Dream. And while his propositions can be frightening at times, he understands that forecasts of superpower collapse will either frustrate or alienate most people, or end up largely ignored -- until it's too late.

[image error]<a href="http://ad.thetyee.ca/www/delivery/ck...." target="_blank"><img src="http://ad.thetyee.ca/www/delivery/avw..." border="0" alt="" /></a> Many of Orlov's forecasts from the previous edition have proven accurate. Orlov's America is a system barely able to sustain itself, ruined by a population bent on a hardened mythology: an iron triangle of home, car and job that is out of touch with the reality of rapidly depleting cheap energy, which made vehicle ownership and suburban home life a gateway to the goal of being middle class. Orlov predicted that as the steady stream of money from employment dried up, the country's depleted social infrastructure would be exposed and the American standard of living would plummet. His forecasts are lived out by the people who have their home in the underground corridors of Las Vegas and in cars across the nation.

Orlov argues that there is a clear recipe for social unrest in the U.S., with approximately 350 million guns, a consumption rate of two-thirds of the world's anti-depressant drugs and a national homicide rate that could be equaled by a 9-11-sized event every month. The can-do American spirit and career-oriented mindset may have served its residents well in the past, but it will be particularly vulnerable in the transition to a post-growth economy. Contrasted to the Russian work ethic during the latter stage of Soviet decline, Orlov says that someone who worked hard and played hard was considered a fool. American career ethics and economic dynamics have lead to patterns of migration that uproot people from communities, something we're witnessing in Canada now -- though this can be a positive in times of collapse, as it makes us more open to strangers and varied living situations than the tightly knit Russian communities Orlov witnessed. Vancouverites know how difficult affordable housing can be, and openness is an asset as living affordability becomes more precarious.

Orlov contrasts the U.S. and the USSR in areas as diverse as housing policies, health care, food production and core societal myths. His explanation of the difference between Soviet and American expectations for education particularly resonated with me. While Soviet schools had far fewer resources, they produced children that knew much more general information and had better conceptual understanding, rather than a focus on exams. At my university in North Carolina, I experienced that exact dynamic. When a professor made a point to avoid specific outlines of what to study, students squirmed with discomfort. In classes with Russian professors, students complained that exams didn't follow homework problems, testing concepts instead. Orlov concludes this is because schools in the U.S. aren't about learning, they are about institutionalization; merely biding the time while kids enter the institution of the workforce, government, a corporation or prison.

Age of opportunity?

While the updated Reinventing Collapse retains many of its first edition's ideas, it reads smoother and makes the case stronger for the collapse of the U.S. But it's not all doom and gloom. Orlov presents very clear and surprisingly optimistic recommendations, revealing an age of opportunity for those willing to adjust their expectations. Orlov thinks black market economies in scavenged material will become the norm in the near future -- and evidence of that is booming, as witnessed by the rapid growth industry of copper and air conditioner theft in the U.S. Orlov explains that expensive health care will become out of reach for the majority, and alternative medicine will grow in popularity as the complex networks that enable pharmaceuticals wither away. He says that instead of building an electric car no one can afford, products and services can be designed to serve the huge and untapped market segment of the permanently unemployed. There will be a need, he says, for low-cost housing opportunities like dormitories, GPS devices for retrieving and locating stashes of gear, or campgrounds that provide garden plots.

The American economy is deeply tied to oil consumption at incredible levels, made possible by the world's reserve currency. Orlov explains that as oil prices increase, the economy will decline, leading to shortages of serviceable equipment and an inability for citizens to consume -- hurting economic activity further, weakening the U.S. dollar and making more oil even further out of reach. Once shortages appear, much of the spare gasoline is wasted idling at the few gas stations still open and hoarded by those with ambition and foresight. Reinventing Collapse explains how even a relatively minor temporary disruption in gasoline could lead to a dramatic shift to a black market economy for fueling vehicles. Another advantage lies herein for Canada as the value of the loonie has been closely tied to oil prices for over a decade.

So where does that leave Canada? While our debt-to-GDP ratio is among the healthiest of the G20, economic ties to the U.S. means we should pay attention. By understanding where the U.S. is headed, perhaps the argument for greater resilience and sustainability here in Canada can be made anew.

Justin Ritchie counts himself among the first refugees from the U.S. to Canada. He covers sustainability and sociological issues as co-host of the Extraenvironmentalist podcast at http://extraenvironmentalist.com. He is the sustainability coordinator for the UBC Alma Mater Society and is working on energy materials as a Master's of Materials Engineering student at the University of British Columbia.

Published on August 21, 2011 09:22

August 18, 2011

No shirt, no shoes, no problem

By Lindsay Curren

By Lindsay CurrenThough we've had Transition Voice for almost a year now, last month was the first time I talked to Russian-American peak oil and economic analyst Dmitry Orlov, whose popular website, Club Orlov, offers both his own thoughts, and a vigorous community of like-minded readers.

Because Orlov takes a more skeptical, less forgiving look at collapse, I think I might have been tuning him out to a degree, considering myself not doomer enough for his club. Or maybe I had Panglossia when it came to him.

But my prejudices were upended when I took the time to read his book Reinventing Collapse: The Soviet Experience and American Prospects . Erik Curren just reviewed the book for us, but I have my own take, too, in fewer words; it's awesome.

If you can call reading about peak oil and collapse "awesome."

Infinitely readable — a page turner even — Orlov's direct experience with Soviet collapse translates into an excellent historical perspective supported by research and a clear context. Yes, he's pretty blunt, and doesn't candy-coat things, but at the same time he's efficient and even somewhat elegant in his writing. It's a quick yet informative read and I highly recommend it.

Soon after I spoke with him and, still nervous about my perception of his intensity, I went into the interview not knowing what this guy would be like.

But like most tough guys, he turned out to be a big pussycat. Very nice, very approachable, funny, insightful, easy to talk to. Rather than finding a stodgy analyst of intellectual information — though he is quite sharp — I'd describe his approach as "moving with, rather than against, collapse." That was one reason for the title for this article, "No shirt, no shoes, no problem." Orlov's is a view seasoned by experience, not just theoretical predictions. So there's an insightful depth there that takes things seriously, while also operating from a deep sense that it's "just life."

Oh, and it was my first shirtless interview. Orlov, that is. He was shirtless. It was a very hot day and I interviewed him via Skype. He was on his boat. It was hot here, too. The heat wave of '11. My shirt stayed on.

Read more...

Published on August 18, 2011 22:00

August 16, 2011

Le pic pétrolier, c'est de l'histoire

[Merci, Tancrède!]

[Merci, Tancrède!]Le baratin mercatique sur la quatrième de couverture de la première édition de mon premier livre, Réinventer l'effondrement, me décrivait comme un théoricien majeur du pic pétrolier. Quand je l'ai vu la première fois, ma mâchoire est tombée — et elle est restée pendante. Vous voyez, si vous parcourez une authentique liste de théoriciens majeurs du pic pétrolier — les Hubbert, Campell, Laherrère, Heinberg, Simmons et quelques autres valant d'être mentionnés, vous ne trouverez pas un seul Orlov parmi eux. En vain chercheriez vous dans les annales et les comptes-rendus de l'Association pour l'étude du pic pétrolier1 la moindre trace de votre humble auteur. Mais à présent que cette bourde est imprimée et en circulation sur tant de copies, je suppose que je n'ai pas d'autre choix que d'essayer d'être à la hauteur des attentes qu'elle crée.

Mes déqualifications mises à part, le moment semble propice à discourir avec un nouveau bout de théorie du pic pétrolier, car c'est l'année où, pour la première fois, presque tout le monde est prêt à admettre que le pic pétrolier est réel, par essence, bien que certains ne soient pas encore tout à fait prêts à l'appeler par ce nom. Il y a seulement cinq ans tout le monde, depuis les officiels du gouvernement jusqu'aux cadres des compagnies pétrolières, traitait la théorie du pic pétrolier comme l'œuvre d'une frange de lunatiques, mais à présent que la production conventionnelle mondiale de pétrole à atteint son pic (en 2005), et que la production mondiale de tous les liquides à atteint son pic (en 2008), tout le monde est prêt à concéder qu'il y a de sérieuses difficultés à accroître l'approvisionnement mondial en pétrole. Et bien que certaines personnes craignent encore d'utiliser le terme pic pétrolier (et que quelques experts insistent encore sur ce que le pic doit être désigné comme un plateau ondulé, ce qui, au moins, est une gracieuse tournure de phrase), les différences d'opinion proviennent d'un refus d'accepter la terminologie du pic pétrolier plutôt que la substance d'une production mondiale de pétrole atteignant son pic. Ceci est, bien sûr, tout à fait compréhensible : il est embarrassant de sauter soudainement de le pic pétrolier est une ânerie ! à le pic pétrolier, c'est de l'histoire ! d'un seul bond. De telles acrobaties ne sont sans danger que si vous vous trouvez être un politicien ou un économiste.

-> Orbite.info

Published on August 16, 2011 22:00

August 14, 2011

De val van Amerika: Een vergelijking met de Sovjetunie

[RC is now available in Dutch.] Wat overkomt de Verenigde Staten bij de aanstaande ineenstorting? Wat zijn de overeenkomsten en verschillen met de val van de Sovjet-Unie? En wat kun je zelf het beste doen als het komt tot een brandstofloos bestaan zonder gezag?

'Wat betekent een maatschappelijke ineenstorting voor de gemiddelde Amerikaan?' Die vraag stelt Dmitry Orlov zich in zijn boek De val van Amerika. Niet de vraag wat precies de val van Amerika in gang zal zetten, wanneer deze exact zal plaatsvinden, of diep hij zal zijn.

Orlov gaat er eenvoudig van uit dat er ergens een afgrond gaapt. De ingrediënten voor de ineenstorting zijn hem duidelijk: ernstige en chronische tekorten bij de productie van aardolie, een ernstig en groeiend tekort op de handelsbalans, op hol geslagen militaire uitgaven en een snel aanzwellende buitenlandse schuld. In combinatie met een militaire nederlaag en wijdverspreide angst voor een dreigende catastrofe moet dat leiden tot een val van Amerika. Wanneer en hoe interesseert Orlov minder. "Probeer gewoon dit beeld voor ogen te houden: het is een supermacht, hij is reusachtig, machtig en staat op het punt in elkaar te donderen. Jij noch ik kunnen daar iets aan doen. Het zou zijn alsof je met wriemelende tenen een tsunami probeert tegenhouden."

Lees verder...

Maar je kunt je ogen er niet voor sluiten. Dus: hoe maak ik dit tastbaar, vroeg Orlov zich af. Als geëmigreerde Rus had hij het juiste middel bij de hand: een vergelijking met de val van de Sovjet-Unie.

"Ik probeer de muur in het voorstellingsvermogen te doorbreken door een vergelijkende analyse waarin ik de daadwerkelijke omstandigheden van voor en na de ineenstorting van de Sovjet-Unie vergelijk met de hypothetische omstandigheden van voor en na de ineenstorting van de Verenigde Staten. Ik richt mij daarbij op categorieën die cruciaal zijn voor overleving: voedsel, huisvesting, transport, onderwijs, financiën, veiligheid en nog een paar andere."

"Het zijn de overeenkomsten op microniveau die ons praktische lessen kunnen leren over hoe kleine groepen met succes het hoofd kunnen bieden aan een economische en sociale ineenstorting. En dat is waar de Russische ervaring van het post-Sovjettijdperk ons heel wat nuttigs te bieden heeft."

Dmitry Orlov wil ons helpen, wat er verder ook te gebeuren staat, een gelukkig en voldaan leven te kunnen leiden. Hij doet dat door de zaak vanuit allerlei invalshoeken te bekijken, ook door de mogelijkheid van een 'zachte landing' te bespreken, en door uitgebreid de manieren de revue te laten passeren waarop je je kunt aanpassen aan het nieuwe normaal en welke carrièremogelijkheden deze toekomst met volkomen nieuwe spelregels in petto heeft.

Het boek wordt nooit zwartgallig. Je schiet bij het lezen geregeld bij in de lach, al is het onderwerp nog zo ernstig.

Downloads Persbericht De Val van Amerika, Dmitry Orlov

1. Ineenstorting voorspellen

2. Ingrediënten voor de ineenstorting

3. De ineenstorting onder ogen zien

4. Is Amerika voorbereid?

5. Kenmerken van de val

6. Ruilgoederen ipv bankbiljetten

7. Nieuwe machtstructuren

8. Gestage uitholling van het bestaan

9. De partij van de ineenstorting

10. Trauma voor geslaagde mannen

11. Zelfkennis als voorbereiding

12. Ontbering leren verdragen

Presentatie

Dageraad der Tegenvoeters

'Wat betekent een maatschappelijke ineenstorting voor de gemiddelde Amerikaan?' Die vraag stelt Dmitry Orlov zich in zijn boek De val van Amerika. Niet de vraag wat precies de val van Amerika in gang zal zetten, wanneer deze exact zal plaatsvinden, of diep hij zal zijn.

Orlov gaat er eenvoudig van uit dat er ergens een afgrond gaapt. De ingrediënten voor de ineenstorting zijn hem duidelijk: ernstige en chronische tekorten bij de productie van aardolie, een ernstig en groeiend tekort op de handelsbalans, op hol geslagen militaire uitgaven en een snel aanzwellende buitenlandse schuld. In combinatie met een militaire nederlaag en wijdverspreide angst voor een dreigende catastrofe moet dat leiden tot een val van Amerika. Wanneer en hoe interesseert Orlov minder. "Probeer gewoon dit beeld voor ogen te houden: het is een supermacht, hij is reusachtig, machtig en staat op het punt in elkaar te donderen. Jij noch ik kunnen daar iets aan doen. Het zou zijn alsof je met wriemelende tenen een tsunami probeert tegenhouden."

Lees verder...

Maar je kunt je ogen er niet voor sluiten. Dus: hoe maak ik dit tastbaar, vroeg Orlov zich af. Als geëmigreerde Rus had hij het juiste middel bij de hand: een vergelijking met de val van de Sovjet-Unie.

"Ik probeer de muur in het voorstellingsvermogen te doorbreken door een vergelijkende analyse waarin ik de daadwerkelijke omstandigheden van voor en na de ineenstorting van de Sovjet-Unie vergelijk met de hypothetische omstandigheden van voor en na de ineenstorting van de Verenigde Staten. Ik richt mij daarbij op categorieën die cruciaal zijn voor overleving: voedsel, huisvesting, transport, onderwijs, financiën, veiligheid en nog een paar andere."

"Het zijn de overeenkomsten op microniveau die ons praktische lessen kunnen leren over hoe kleine groepen met succes het hoofd kunnen bieden aan een economische en sociale ineenstorting. En dat is waar de Russische ervaring van het post-Sovjettijdperk ons heel wat nuttigs te bieden heeft."

Dmitry Orlov wil ons helpen, wat er verder ook te gebeuren staat, een gelukkig en voldaan leven te kunnen leiden. Hij doet dat door de zaak vanuit allerlei invalshoeken te bekijken, ook door de mogelijkheid van een 'zachte landing' te bespreken, en door uitgebreid de manieren de revue te laten passeren waarop je je kunt aanpassen aan het nieuwe normaal en welke carrièremogelijkheden deze toekomst met volkomen nieuwe spelregels in petto heeft.

Het boek wordt nooit zwartgallig. Je schiet bij het lezen geregeld bij in de lach, al is het onderwerp nog zo ernstig.

Downloads Persbericht De Val van Amerika, Dmitry Orlov

1. Ineenstorting voorspellen

2. Ingrediënten voor de ineenstorting

3. De ineenstorting onder ogen zien

4. Is Amerika voorbereid?

5. Kenmerken van de val

6. Ruilgoederen ipv bankbiljetten

7. Nieuwe machtstructuren

8. Gestage uitholling van het bestaan

9. De partij van de ineenstorting

10. Trauma voor geslaagde mannen

11. Zelfkennis als voorbereiding

12. Ontbering leren verdragen

Presentatie

Dageraad der Tegenvoeters

Published on August 14, 2011 22:00

August 10, 2011

The Sledge-O-Matic

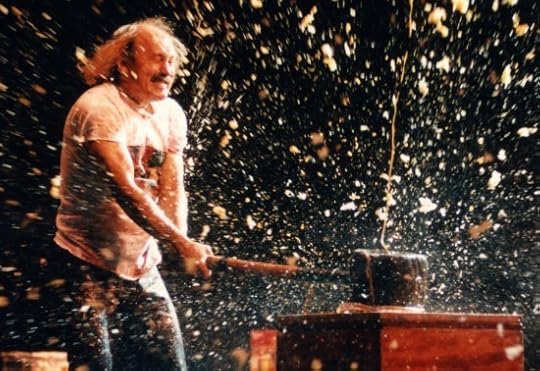

Photo: gallaghersmash.com.

[A generally pleasant and helpful book report by Eric Curren. I took the liberty of taking out a paragraph where he sounds too much like a defensive American. There is no room for national inferiority complexes here. Sorry to admit, I haven't read de Toqueville. He talked about democracy in America; what's that? Nor have I heard of Gallagher.]

Dmitry Orlov scares the crap out of me.

The relentlessly doomerish boss of ClubOrlov.com has become famous in peak oil circles for presiding over a kind of comedy club from hell where a rabid fan base celebrates the coming fall of the American Empire under the load of peak debt while devouring posts on such subjects as the future of sailing ships and ways for dead people to send text messages. The site's sidebar lists topic tags including cannibalism, ruins and Siberia.

Even Orlov's name is scary, suggesting to the Anglo-Saxon ear a marriage of Orwell and Karlov — evoking George and Boris respectively, each in his own way a master of horror.

But while his online homies clearly relish Orlov's hard edge, it would be a shame if his intimidating reputation put off a wider audience from reading his brilliant book, recently re-released.

Here, I'd like to propose a different, hopefully more accessible way of seeing Orlov: as a foreign-born observer of American culture in the mold of Alexis de Tocqueville. But with a little bit of Gallagher thrown in — yes, that Gallagher, the prop comic with the goofy hair and suspenders, popular in the 1980s for smashing watermelons on stage.

Hypocrisy in America

I'll start by admitting I think that Orlov's Reinventing Collapse: The Soviet Experience and American Prospects is just as perceptive a read on the American mind and the American system as was de Tocqueville's Democracy in America.

"As one digs deeper into the national character of the Americans, one sees that they have sought the value of everything in this world only in the answer to this single question: how much money will it bring in?" said de Tocqueville. Compare Orlov on the American's "primitive idolization of money":

The only thing that makes an American good is the goodly quantity of dollars lining his pockets. This is what makes the ritualistic acts of humiliation heaped on the poor and the unfortunate so politically popular even with the very slightly well-to-do; just utter the fashionable term of abuse — "welfare queen" or "illegal immigrant" — and citizens line up in an orderly gamut, ready to dispense corporal punishment.It may seem that Orlov is more provocative than de Tocqueville, but historians say that in its time, readers in both the US and the author's native France thought Democracy in America was pretty edgy too. It's easy to see why two centuries of scholars and pundits haven't stopped quoting a guy who says stuff like this: "I know of no country in which there is so little independence of mind and real freedom of discussion as in America."

And though Orlov doesn't mention de Tocqueville, the two should be good friends. Presciently, in 1835 De Tocqueville predicted the superpower rivalry between the US and Russia that would become the backstory to Orlov's analysis.

The Frenchman also foresaw key threats to American democracy that ultimately led to the debased nation that Orlov finds today: the rise of a plutocracy, the dominance of mass culture over thinking for oneself, a preoccupation with material goods and the isolation and alienation of the individual.

The hammer and the sickle, and the hammer again

Orlov, who was born in Leningrad, emigrated to the US in the seventies and then made repeated trips back home, which enabled him to witness the collapse of the USSR and its aftermath from a perspective both Russian and American. No surprise that he's built a career out of making unflattering comparisons of the US to his home country.

Orlov has earned a fearsome reputation as a doomer who not only predicts, but even seems to relish, the collapse of American society, while he disdains political activism, celebrates apathy as a healthy coping strategy and warns that there's nothing anybody can do to fix things. Yet, in his book Orlov projects genuine goodwill, showing evident compassion for the "big, rowdy party that was this country, with its lavish, garish, oversized, dominating ways."

As the party winds down, Orlov reminds us that "people like to party together but they like to nurse their hangovers alone." So, he offers no one-size-fits-all plan for surviving the coming turmoil. But in classic American fashion, he urges each of us to come up with our own plan.

"You should figure out what it is you absolutely need to lead a healthy, happy, fulfilling existence. Then, figure out a way to continue getting it once the US economy collapses, taking a lot of society with it. (This is easier said than done; good luck!)"

For example, Orlov himself lives on a sailboat and says that today's economic downturn is probably a good time for readers to seek their own boat at a fire-sale price. At the same time, living on a boat is not for everybody, and Orlov gives lots of other ideas to prepare for a future economy that's basically beyond employment and beyond money.

On the way down

Of course, in his place in the cycle of American imperial rise and fall, Orlov differs from de Tocqueville. That could help explain the difference in tone between the two writers. Despite all his criticism of America's money-grubbing, crowd-worshipping character, the Frenchman often flattered our sensibilities and saw a bright future for our nascent democracy. By contrast, the Russian has little good to say about our character and even less good to say about our prospects.

Measure after measure, Americans are less prepared to deal with a Soviet-style collapse than his people were. In Russia, for example, when the economy collapsed few people lost their homes, because the buildings were owned by the state and more-or-less permanently assigned to their occupants. By contrast, in the US, private landlords and mortgage-holders are unlikely to tolerate deadbeat tenants or defaulting homeowners for very long. In an economic collapse, evictions could dwarf the foreclosure crisis of the last few years.

The collapse party

At the same time, despite a few good qualities (our friendliness to strangers makes us excellent roommates, for example, which could come in handy during a housing crisis), Orlov thinks that Americans are pampered fools who are much less prepared to fend for ourselves than the wily Russians were.

Take food for instance. Many urban Russians had dachas outside of town where they could grow food for their own use and for barter. But in the US, not only do few besides the relatively wealthy own a second home — even fewer of us bother to plant a kitchen garden. When grocery store shelves start to empty out, the dependent American food eater will be like a baby who's lost his bottle. And a nation raised on cheap eats and easy livin' could soon face the unimaginable: widespread hunger.

So, what Orlov is really doing is trying to show that the American system is hard and unforgiving but that the American people are ripe and soft, like a big watermelon.

And for me, that's where Orlov meets that other analyst of the American character, Gallagher. And I don't mean the racist clown that the un-funny old man has become today, "a hate-filled, right-wing loon," according to Salon. I mean classic Gallagher, the guy we cared about in the 1980s for only one reason: the Sledge-O-Matic.

This routine with the mallet and an unlucky piece of summer fruit, computer keyboard or other highly smashable item of everyday life clearly spoke to something deep in the American psyche. It wasn't just the adolescent fun of busting things up. Gallagher also connected to a pervasive if quiet discomfort among the public with our culture of material abundance and wastefulness at the period of its very height.

I don't think Orlov takes a Sledge-O-Matic to America's national pride just as a Russian's revenge. Instead, I believe him when he says he wants to help Americans wake up from their own debilitating national myths in time to save themselves from disaster.

"Sledge-O-Matic removes unwanted fingerprints from walls," says Gallagher as pitchman. "Sledge-O-Matic also removes unwanted walls from fingerprints."

Published on August 10, 2011 22:00

July 31, 2011

Myślenie w liniach prostych

Thank you, Marcin, for another translation. Here is the original: Thinking in Straight Lines.

Thank you, Marcin, for another translation. Here is the original: Thinking in Straight Lines.Spójrzmy prawdzie w oczy – my jako cywilizowana, wyedukowana, oświecona część ludzkości domagamy się, aby otaczające nas rzeczy były proste. Niech prymitywni tubylcy żyją w malowniczych i praktycznych okrągłych chatkach – my życzymy sobie abstrakcyjnych, stalowych pudełek i betonu platerowanego szkłem, z mnóstwem przyjemnych linii prostych, autentycznie wertykalnych, horyzontalnych, planarnych powierzchni i obfitością kątów prostych cieszących oko. Niech tubylcy wypełniają sobie dni wałęsaniem się w górę i w dół malowniczymi, wijącymi się ścieżkami, wytyczonymi przez pasące się zwierzęta – kiedy budujemy drogę, bierzemy mapę i przykładamy do niej linijkę i wszystko, co stoi na drodze tej linijki, malownicze czy nie, musi być wysadzone dynamitem, wyrównane buldożerem, ponieważ każdy wie, że podróżowanie w linii prostej jest bardziej wydajne.

Większości z nas to odpowiada, zatem uznajemy linie proste za naturalne. W rzeczywistości nasz świat zawiera tylko dwa rodzaje naturalnych zjawisk, które dają początek liniom prostym: obiekty spadają lub wiszą w prostych, pionowych liniach i promień światła podróżuje w linii prostej; poza liniami pionu i liniami widzenia wszystko jest albo zakrzywieniem, albo zygzakiem. Skoro w zdecydowanie większym stopniu nasze środowisko jest sztuczne – i po brzegi wypchane liniami prostymi oraz płaskimi powierzchniami horyzontalnymi i wertykalnymi – sporadycznie bywamy zmuszeni konfrontować się z tym faktem. Oczywiście, bardziej wyrobieni naukowo pośród nas wiedzą, że linie proste są jedynie wygodną fikcją. Zaczynamy od konceptualnych ram przestrzeni, które składają się z osi x, y, z i następnie przechodzimy do zmuszania naszych obserwacji, aby mieściły się w tych ramach, aż do momentu, kiedy niedopasowanie staje się zbyt oczywiste, by je zignorować, jak w przypadku obiektów zrzuconych z orbity, czy światła z odległych galaktyk, które bywa tak dalece zakłócone przez galaktyki pobliskie, że obraz przypomina rozmazaną plamę.

Jednakże fikcja ta jest faktycznie bardzo wygodna. Po pierwsze, wszystkie linie proste są wzajemnie wymienialne i kompatybilne. Kiedy budujemy mamy w zwyczaju kłaść rzeczy 'na' lub 'obok' innych; jeżeli posiadają linie proste, wówczas nie wymaga to wymyślnego dopasowania – możemy po prostu połączyć je bezceremonialnie w jakikolwiek sposób i skutecznie przejść do następnego ćwiczenia w budowaniu pudełek. Kiedy odwiedzamy skład drzewny raczej nie kupujemy drewna, tylko przecięte przezeń linie proste. Drzewa wiedzą znacznie więcej od nas na temat konstruowania maksymalnie wydajnych drewnianych struktur, ale my lubimy linie proste, zatem przecinamy najmocniejszą część drzewa – koncentryczne pierścienie, które składają się na pień – aby wykonać idealnie prosty kij. Moglibyśmy budować piękne, mocne, długowieczne struktury wykorzystując budulec drzewny wyrosły stosownie do potrzeb (tak, jak robią to niektórzy z nas), lecz generalnie tego nie robimy, ponieważ jesteśmy leniwi mentalnie, zawsze w nadmiernym pośpiechu, a z linii prostych uczyniliśmy fetysz.

Nie jest specjalnym zaskoczeniem, że nasze upodobanie do linii prostych przekłada się na sposób, w jaki myślimy o relacjach między obiektami – konstruowane przez nas mentalne modele naszego świata. Przykładowo za kwestię prawości i uczciwego postępowania uznajemy, aby cena była linearnie proporcjonalna do ilości otrzymywanych produktów: jeżeli płacisz dwa razy więcej powinieneś otrzymać dwa razy więcej ziemniaków. Upusty ilościowe są akceptowalne i czasem oczekiwane, ale wycena według krzywej jest ogólnie postrzegana jako podejrzana. Nie ufamy krzywiznom. Funkcje schodkowe są w porządku, ponieważ składają się z segmentów złożonych z linii prostych. Jesteśmy w stanie ścierpieć przedziały podatkowej skali, ale spróbuj opodatkować ludzi w oparciu o formułę nielinearną i z pewnością wybuchnie podatkowa rewolta. Gdyby ziemniaczany rynek był produktem biologicznej ewolucji, a nie wymysłem ludzkim, prawdopodobnie wglądałby tak: cena byłaby pewną nielinearną funkcją, która jest wprost proporcjonalna do wartości netto klienta, a liczba wydanych ziemniaków byłaby pewną nielinearną funkcją, która jest odwrotnie proporcjonalna do jego talii netto. Ulokujcie sakwy z pieniędzmi na jednej szali, swoje zwały tłuszczu na drugiej i część ziemniaków wypadnie. Taki naturalny mechanizm regulacji powstrzymałby otyłych i majętnych żarłoków przed wyprzedzeniem w konsumpcji całej reszty, lecz tak być nie może, bowiem mamy silną kulturową skłonność preferowania prostego, linearnego związku między ilością i ceną.

Linie proste są popularne wśród sklepikarzy i ich klientów, ale nikt nie wielbi pomiarowej krawędzi bardziej od technokraty. Dane z prawdziwego świata ogólnie przypominają kolekcję niepowtarzalnych artefaktów opisanych przez kwalitatywnie odmienne własności oraz wywnioskowane relacje, wszystkie ulegające fluktuacjom w czasie i w taki sposób, który opiera się bezpośredniemu zastosowaniu pomiarowej krawędzi. Dlatego pierwszy krok to określenie ilościowe własności oraz – jeżeli jest to w ogóle możliwe – zignorowanie relacji. Następny krok to wybór tylko dwóch parametrów i przedstawienie tych artefaktów jako punktów na kawałku milimetrowego papieru. Voilà: znaleziony został linearny związek między dwoma skomplikowanymi zjawiskami, które teraz mogą być potraktowane jako prawdziwe i obiektywne – coś, czym można podzielić się ze swoimi kolegami i wykorzystać jako podstawę strategii działania – ponieważ zawiera linię prostą, która mówi, że jedna rzecz jest proporcjonalna do innej, zatem wiemy jakiego oczekiwać rezultatu, kiedy zaburzymy jedną lub drugą.

Linie proste są również popularne wśród inżynierów. Inżynierowie pracują ciężko, aby zaprojektować linearne, niezmienne w czasie systemy, w których wydajność jest wprost proporcjonalna do wkładu w każdym upodobanym przez nas momencie. Z ich perspektywy odchylenia od zachowania linearnego są defektami. Z naszej perspektywy także: możemy je usłyszeć, kiedy wzmacniacz audio ma nielinearne efekty, ponieważ zniekształca dźwięk; możemy je dostrzec, kiedy optyka zniekształca obraz. Możemy odróżnić linię prostą od zakrzywionej bez jakichkolwiek narzędzi. Ale narzędzia matematyczne stosowane przez inżynierów do projektowania tych linearnych, niezmiennych w czasie systemów są szczególnie dobre – jak na matematyczne narzędzia. Matematyka może być nawet przyjemną rozrywką jako rodzaj zaawansowanej gry dla filozofów, ale jej znakomita większość z punktu widzenia inżyniera jest problematyczna. Można opisać praktycznie wszystko stosując zestaw równań różniczkowych, ale przeważająca ilość interesujących zjawisk – przykładowo zachowanie płatu skrzydła w strumieniu powietrznym, czy zachowanie rozgrzanych gazów w komorze spalania – prowadzi do równań, które nie sposób rozwiązać analitycznie; podejść do nich można jedynie stosując metody numeryczne, przy wykorzystaniu komputera. Skonstruowany zostaje matematyczny model i rzuca się weń przypadkowymi liczbami, aby przekonać się, co z tego wyniknie. Jednakże linearne, niezmienne w czasie systemy są opisywane przy zastosowaniu niepowtarzalnie układnej klasy równań różniczkowych, mających analityczne rozwiązania o zamkniętej formie, które dostarczają w bezpośredni sposób odpowiedzi na pytania projektowe, zatem studenci inżynierii ćwiczą je do znudzenia, a w przyszłości projektują i budują wszelkiego rodzaju maszynerię zachowującą się tak linearnie, jak to tylko możliwe, od skromnych pokręteł głośności po złożone płaszczyzny sterowania samolotem. Z kolei ta układna, przewidywalna maszyneria pozwala nam osiągnąć linearne efekty w gospodarce: zbuduj więcej rzeczy – otrzymasz proporcjonalnie więcej pieniędzy; wydaj więcej pieniędzy – otrzymasz proporcjonalnie więcej rzeczy. Jak można podejrzewać, koncepcja ta sprawdza się do pewnego stopnia.

Przypomnijmy raz jeszcze: linie proste są jedynie wygodną fikcją. Nie ma fizycznego analogu matematycznej linii prostej, który biegnie od minus nieskończoności do plus nieskończoności. W najlepszym razie możemy użyć wszystkich kunsztownych zabiegów, aby stworzyć względnie krótkie segmenty linii prostej. Prawda wygląda tak, że inżynierowie nie potrafią stworzyć linearnych systemów; mogą jedynie stworzyć systemy, które demonstrują linearne zachowanie w obrębie swojego linearnego obszaru. Poza tym obszarem przyroda robi to, co potrafi najlepiej: wykonuje szalone zakrzywienia i zygzaki i ogólnie zachowuje się w przypadkowy i nieprzewidywalny sposób. Znanym z naszego codziennego doświadczenia przykładem na to, co się dzieje, kiedy przekroczymy granice linearnego obszaru jest fenomen przeciążenia wzmacniacza audio. Efekt będący jego rezultatem nazywa się przesterowaniem (clipping) i brzmi jak wyjątkowo nieprzyjemny, przeszywający, zgrzytliwy dźwięk. Są tylko dwa rozwiązania: obniżyć głośność (powrócić do parametrów obszaru linearnego) lub zdobyć wzmacniacz o większej mocy.

W sferze ekonomii efekty przekroczenia granic obszaru linearnego mogą być nawet bardziej nieprzyjemne. Budowanie domów pozostające w granicach tego obszaru generuje więcej bogactwa, ale tuż poza obszarem dość szybko zaczynają się dziać rzeczy dziwne: ceny nieruchomości odnotowują katastrofalny spadek, hipoteki tracą wartość i budowanie większej liczby domów staje się wybitnie złym pomysłem. W granicach obszaru linearnego posiadanie większej ilości pieniędzy czyni cię bogatszym, w tym sensie, że jesteś zdolny zakupić więcej rzeczy, ale poza granicami obszaru jesteś zmuszony zdać sobie sprawę, że skoro większość pieniędzy istnieje dzięki pożyczaniu, to de facto stanowi zadłużenie i kiedy pojawia się niewypłacalność, bez względu na to jak dobrze prezentuje się na papierze twoja wartość netto, stajesz w obliczu ubóstwa, które dodatkowo pogarsza fakt, że nie masz praktyki w egzystowaniu bez grosza. W granicach obszaru linearnego inwestowanie większych sum w produkcję energii generuje więcej energii, lecz niedaleko poza nim produkcja energii spada i może niechcący zniszczyć całe sektory przemysłu i ekosystemy.

Skoro linearność jest fikcją użyteczną tylko do pewnego stopnia, to jak wygląda kwestia niezmienności w czasie? Niewątpliwie ona także musi mieć swoje granice. Wciskanie pedału gazu może za każdym razem wywołać przyspieszenie, ale ilość paliwa w baku zmniejsza się monotonicznie, aż nie pozostanie w nim nic. Jeżeli chodzi o bardziej złożone, dynamiczne systemy – przemysły, gospodarki, społeczeństwa – to mogą one do pewnego stopnia reagować na zewnętrzne bodźce w linearny i niezmienny w czasie sposób, ale za tą stabilną fasadą ich zdolności ulegają erozji, ich zasoby zmniejszają się, ich złożoność wzrasta i poza pewnym punktem rozpoczyna się całkowicie odmienny proces: proces upadku. Takie systemy generalnie nie stają się mniej skomplikowane, nie redukują spontanicznie swoich rozmiarów, czy zużycia surowców, reagując przy tym na zewnętrzne bodźce w kontrolowany, linearny sposób.

Tak mocno i tak głęboko wrósł w nas nawyk myślenia w liniach prostych, że często nie potrafimy sobie wyobrazić, iż moglibyśmy kiedykolwiek opuścić obszar linearny, a kiedy już tak się stanie nie potrafimy tego dostrzec, chociaż dowody mamy przed sobą. Specjalistyczne analizy sądowe katastrof lotniczych czasem ujawniają, że w swoim ostatnim odruchu pilot wyrwał konsolę sterowania z podłogi kokpitu – akt, który wymaga nadludzkiej siły – tak mocno ciągnął za drążek, aby podnieść dziób samolotu. Jestem pewien, że istnieje całe mnóstwo pilotów – we wszystkich sferach życia – którzy wybiorą katastrofę, z całej siły ściskając ster, ze wzrokiem wbitym w odległy, nieistotny lub fikcyjny horyzont, zamiast wcisnąć guzik od katapulty. Doświadczenie całego ich życia ograniczało się do obszaru linearnego i dlatego nie potrafią sobie wyobrazić, że mógłby kiedykolwiek się skończyć.

Jeden szczególnie istotny przykład takiego myślenia wiąże się z kwestią Peak Oil zazwyczaj wyrażaną jako założenie, iż globalna produkcja ropy zdążyła już osiągnąć lub osiągnie niebawem swój szczyt wszech czasów, a następnie rozpocznie stopniowy spadek rozłożony na przestrzeni kilku dekad. Wyczerpanie nafty jest modelowane jako linearna funkcja produkcji ropy: kilka procent rocznie, utrzymujących się z sezonu na sezon mniej więcej na stałym poziomie. Jednocześnie zużywanie ropy przez społeczeństwa przemysłowe jest często użytecznie charakteryzowane jako uzależnienie. Przećwiczmy tę metaforę i przekonajmy się dokąd nas zaprowadzi. Załóżmy, że mamy do czynienia z narkomanem, który cierpi na wzbierający heroinowy nałóg i który zmuszony jest naciągać z coraz większym mozołem, aby zaliczyć kolejną działkę. Teraz załóżmy, że globalna produkcja heroiny osiąga swój szczyt, ceny idą w górę, zaopatrzenie słabnie i nasz ćpun musi rozpocząć obcinanie dawki. Po upływie niezbyt długiego czasu mamy już do czynienia z chorym narkomanem, który nie jest w stanie opuścić swojego lokum i naciągać celem pozyskania następnej działki. Zaraz potem mamy upadek rynku heroiny, ponieważ narkomani zostali zmuszeni w mniejszym lub większym zakresie rzucić nałóg. To zaburzenie na rynku, nawet tymczasowe, sprawia, że produkcja narkotyku zmniejsza się jeszcze szybciej, koszty produkcji i ryzyko towarzyszące wzrastają itd. Poza pewnym punktem rynek heroiny nie byłby już charakteryzowany jako linearny, niezmienny w czasie system, w którym im więcej płacisz, tym więcej otrzymujesz w dowolnym momencie, ponieważ tak niewiele pozostałoby do rozdystrybuowania.

Podobnie jest z ropą. Zaraz po huraganie Katrina w niektórych południowych stanach USA miało miejsce zaburzenie dostaw paliwa. Ludzie pisali do mnie, że w rezultacie nastąpił natychmiastowy chaos: społeczeństwo szybko przestało funkcjonować na wszystkich poziomach. Niedobór był tymczasowy i szybko o nim zapomniano, ale gdyby był to niedobór długoterminowy, systemowy, z pewnością zaobserwowalibyśmy wszystkie typowe następstwa: zapasy paliwa wyparowane na skutek tankowania baków po brzegi i spalania podczas jazdy w kółko, z pełnym zbiornikiem i baterią kanistrów w bagażniku; mnóstwo paliwa zmarnowanego podczas jazdy w poszukiwaniu benzyny i podczas postojów w długich kolejkach do dystrybutorów; mnóstwo spuszczania benzyny ze zbiorników i w rezultacie wielu porzuconych na drogach kierowców; wielu ludzi nie zdolnych dotrzeć do pracy; niedługo potem paniczne wykupowanie produktów pierwszej potrzeby, plądrowanie i zamieszki, sparaliżowany handel, federalne służby przywracające porządek na ulicach, godzina policyjna, ograniczenia wszelkich form podróżowania, przymusowe dni wolne, kryzys bilansu płatniczego i w końcu powszechna niezdolność do finansowania dalszej produkcji lub importu ropy. Wszystkie te zaburzenia wywołują dalsze przyspieszenie spadku produkcji nafty, wraz z całą gospodarczą działalnością, aż do momentu, kiedy zapotrzebowanie na ten towar staje się po prostu znikome. W miarę wygasania aktywności globalnego przemysłu naftowego, platformy wiertnicze, rafinerie i rurociągi wychodzą z użycia i nie nadają się do eksploatacji. Zamiast gładkiego, kilkuprocentowego rocznego spadku mielibyśmy sytuację, którą Douglas Adams opisałby jako "spontaniczną awarię egzystencji."

Jestem pewien, że niektórzy ludzie chcieliby, żebym bystro nakreślił swoją pomiarową krawędź, naniósł parę linii prostych i sporządził prognozę: Jakie przewiduję ceny? O jakich wartościach produkcji za dziesięć, dwadzieścia lat możemy mówić? Cóż, w moim odczuciu to kompletna strata czasu. Wolę go spędzić ucząc się jak przycinać drzewa z myślą o budowaniu z okrągłego drewna. Przyszłość z pewnością będzie nielinearna i jestem zupełnie przekonany, że będą w niej drzewa. Wspominam o tym dlatego, że jest tam gdzieś kilkoro pilotów, którzy, mam nadzieję, zachowają przytomność umysłu i wcisną guzik od katapulty, zamiast kurczowo trzymać ster, ze spojrzeniem zatrzymanym na sztucznym horyzoncie.

Published on July 31, 2011 07:25

July 23, 2011

Dead Souls

p { margin-bottom: 0.08in; }a:link { }

With each passing week more and more of us become ready to concede that economic growth is no longer possible. Economic development, on the old model, which UN Secretary Ban Ki-moon recently characterized as a "global suicide pact," is becoming constrained by the limits of natural resources of the finite planet, energy, arable land and fresh water foremost among them, and stressed further by extreme weather events that increase in frequency due to the rapidly destabilizing climate. Since the narrowly averted financial collapse of 2008, aggregate indicators of economic growth have been anemic at best, and would be negative were it not for a dramatic expansion in public debt and aggressive financial manipulation by American and European central banks. These methods are only effective up to a point. Some time ago it became apparent that we have reached the point of diminishing returns on debt expansion: further expansion of public debt decreases rather than increases GDP. Perhaps the next realization to hit us is that public debt is in runaway mode: it will continue to go up whether government spending is cut or increased. From this it follows that the government's days are numbered; but few people are ready to make this leap yet.

With each passing week more and more of us become ready to concede that economic growth is no longer possible. Economic development, on the old model, which UN Secretary Ban Ki-moon recently characterized as a "global suicide pact," is becoming constrained by the limits of natural resources of the finite planet, energy, arable land and fresh water foremost among them, and stressed further by extreme weather events that increase in frequency due to the rapidly destabilizing climate. Since the narrowly averted financial collapse of 2008, aggregate indicators of economic growth have been anemic at best, and would be negative were it not for a dramatic expansion in public debt and aggressive financial manipulation by American and European central banks. These methods are only effective up to a point. Some time ago it became apparent that we have reached the point of diminishing returns on debt expansion: further expansion of public debt decreases rather than increases GDP. Perhaps the next realization to hit us is that public debt is in runaway mode: it will continue to go up whether government spending is cut or increased. From this it follows that the government's days are numbered; but few people are ready to make this leap yet.

Against this background of economic stagnation and decay and widespread financial insolvency one sector is experiencing a boom time: Silicon Valley is booming again, and tech start-up IPOs are doing well. Social networking and mobile computing are hot, and some are expecting them to power the global economy out of the doldrums. Others contend that this industry segment is, and will remain, far too small to pick up the slack for the rest of the resource-strapped global economy. What neither side seems to grasp is this: as the virtualized realm of cyberreality and social networking takes over daily life, the actual physical economy will matter less and less (to those who are still alive and have an internet connection). What these new gadgets offer is, simply put, escapism. In a world of dwindling resources, where each person's share of the physical realm decreases over time, it is no wonder that physical reality fails to satisfy. But thanks to the new, intimate, glowing handheld mobile computing devices, the unsatisfactory real world can be blotted out, and replaced with a cleansed, bouncy, shiny version of society in which little avatars utter terse little messages. In the cyber-realm there are no sweaty bodies, no cacophony of voices to suffer through—just a smooth, polished, expertly branded user experience.

While riding the subway through the Boston rush hour, I have been able to observe just how well these personal electronic mental life support units work in shielding people from the sight of their fellow-passengers, who are becoming a rougher and rougher-looking crew, with more and more people in obvious distress. By focusing all of their attentions on the tiny screen, they are also spared the sight of our well-worn and crumbling urban infrastructure. It is as if the physical world doesn't really exist for them, or at least doesn't matter. But as Masanobu Fukuoka put it, "If we throw Mother Nature out the window, she comes back in the door with a pitchfork," and as we ignore the physical realm, the physical economy (the one that actually keeps people fed and sheltered and moves them about the landscape) shrinks and decays. The inevitable result is more and more of these cyber-campers and their gadgets will drop off the network, shrivel, and die with nary a tweet to signal their demise.

And this is, of course, a shame: a terrible and unnecessary loss to the online community. Yes, resource depletion cannot be turned back, nor can catastrophic climate change. Yes, the global economy will crumble as a result, and people will die. But why should their online personae die with them? That, at least, seems preventable. Not only that, but letting users die is bad for the economy: companies like Facebook, Twitter, Google, and numerous tech start-ups are judged based on the size of their user base. Some of them may not generate much in the way of revenue, but if they have millions of users then everyone assumes they must be worth something. But if the physical economy continues to cave in on itself and their user base starts to drop off like flies in autumn, then that would be bad for a company's valuation and stand in the way of it securing additional rounds of financing. If it finds a way to compensate, then all would be well with their business plan, and their innovative social networking platform might indeed help power the global economy out of the doldrums and into some other nautical metaphor, but if not, then it would be doomed. Doomed! And investors don't like the sound of the word "doomed."

The solution is as obvious as it is counterintuitive, and it comes from a classic of Russian literature: Nikolai Gogol's Dead Souls. It details the exploits of one Chichikov, who rambles around the Russian countryside, visiting estates and convincing their owners to sell to him their dead peasants. With the dead peasants' papers in hand Chichikov is then able to use them as collateral for loans and to mortgage them (omitting to mention, of course, that they are dead). Correspondingly, the solution for the social networking tech start-ups, moving forward, is to leverage their dead users. This, after all, seems like a humane and caring thing to do: why let someone's online persona die with them? This is often a shock to the other users, who most likely have never even met the deceased person in real life, and don't particularly care whether he or she physically exists. It was once said that on the Internet nobody knows whether you are dog; so let it be that nobody knows whether you are even alive. In a society that lavishes hundreds of thousands of dollars on end-of-life medical care, why not save a little of that money for the cyber-afterlife? For people whose lives are mostly lived on the Internet, technology that extends their online persona past their physical death would be life-extending technology par excellence, and a fitting tribute.

The technical challenge is considerable, but it is by no means insurmountable. For example, let's say you have a dead user who likes cats. Now, it is well known that uploading pictures of cats is a good way to get "karma points." In life, our erstwhile cat-lover would have immediately responded with a succinct message such as "UR KITTEH RLY CUTE LOLZ" by thumbing it into some handheld device. After our user's untimely demise, the same function would be performed by a computer program. To paraphrase Descartes, "Txto, ergo sum." Here is a proof of concept that took me just a minute or two to code up:

With a bit of effort this sample code can be extended to cover the typical set of the eternally resting user's online utterances. (Of course, a more contemporary way to implement it would be as a web service. And, of course, it would have to be a RESTful one.)

With a bit of effort this sample code can be extended to cover the typical set of the eternally resting user's online utterances. (Of course, a more contemporary way to implement it would be as a web service. And, of course, it would have to be a RESTful one.)

Thus, generating tweets, SMS messages and posting comments, perhaps even generating entire blog posts that convincingly mimic those of a living user is an eminently surmountable technical challenge. But a much harder problem is to keep our dead user in the vanguard of exciting new social movements and fashions that sweep through the net with lightening speed. Just recently "planking" was all the rage.

This is "planking"

This is "planking"

But now "planking" is just completely last week and everyone who is cool and hip is into "owling."

This is "owling"Without a timely infusion of such new trends our deceased user's persona would grow stale and unpopular. But perhaps that is as it should be: let the living rise in popularity while the dead slowly become de-friended and de-linked, eventually lapsing into oblivion. After all, all we are doing is buying some time. The last person out, please remember to shut down the cloud, because what would be the use of letting dead people talk to each other?

This is "owling"Without a timely infusion of such new trends our deceased user's persona would grow stale and unpopular. But perhaps that is as it should be: let the living rise in popularity while the dead slowly become de-friended and de-linked, eventually lapsing into oblivion. After all, all we are doing is buying some time. The last person out, please remember to shut down the cloud, because what would be the use of letting dead people talk to each other?

With each passing week more and more of us become ready to concede that economic growth is no longer possible. Economic development, on the old model, which UN Secretary Ban Ki-moon recently characterized as a "global suicide pact," is becoming constrained by the limits of natural resources of the finite planet, energy, arable land and fresh water foremost among them, and stressed further by extreme weather events that increase in frequency due to the rapidly destabilizing climate. Since the narrowly averted financial collapse of 2008, aggregate indicators of economic growth have been anemic at best, and would be negative were it not for a dramatic expansion in public debt and aggressive financial manipulation by American and European central banks. These methods are only effective up to a point. Some time ago it became apparent that we have reached the point of diminishing returns on debt expansion: further expansion of public debt decreases rather than increases GDP. Perhaps the next realization to hit us is that public debt is in runaway mode: it will continue to go up whether government spending is cut or increased. From this it follows that the government's days are numbered; but few people are ready to make this leap yet.

With each passing week more and more of us become ready to concede that economic growth is no longer possible. Economic development, on the old model, which UN Secretary Ban Ki-moon recently characterized as a "global suicide pact," is becoming constrained by the limits of natural resources of the finite planet, energy, arable land and fresh water foremost among them, and stressed further by extreme weather events that increase in frequency due to the rapidly destabilizing climate. Since the narrowly averted financial collapse of 2008, aggregate indicators of economic growth have been anemic at best, and would be negative were it not for a dramatic expansion in public debt and aggressive financial manipulation by American and European central banks. These methods are only effective up to a point. Some time ago it became apparent that we have reached the point of diminishing returns on debt expansion: further expansion of public debt decreases rather than increases GDP. Perhaps the next realization to hit us is that public debt is in runaway mode: it will continue to go up whether government spending is cut or increased. From this it follows that the government's days are numbered; but few people are ready to make this leap yet.Against this background of economic stagnation and decay and widespread financial insolvency one sector is experiencing a boom time: Silicon Valley is booming again, and tech start-up IPOs are doing well. Social networking and mobile computing are hot, and some are expecting them to power the global economy out of the doldrums. Others contend that this industry segment is, and will remain, far too small to pick up the slack for the rest of the resource-strapped global economy. What neither side seems to grasp is this: as the virtualized realm of cyberreality and social networking takes over daily life, the actual physical economy will matter less and less (to those who are still alive and have an internet connection). What these new gadgets offer is, simply put, escapism. In a world of dwindling resources, where each person's share of the physical realm decreases over time, it is no wonder that physical reality fails to satisfy. But thanks to the new, intimate, glowing handheld mobile computing devices, the unsatisfactory real world can be blotted out, and replaced with a cleansed, bouncy, shiny version of society in which little avatars utter terse little messages. In the cyber-realm there are no sweaty bodies, no cacophony of voices to suffer through—just a smooth, polished, expertly branded user experience.

While riding the subway through the Boston rush hour, I have been able to observe just how well these personal electronic mental life support units work in shielding people from the sight of their fellow-passengers, who are becoming a rougher and rougher-looking crew, with more and more people in obvious distress. By focusing all of their attentions on the tiny screen, they are also spared the sight of our well-worn and crumbling urban infrastructure. It is as if the physical world doesn't really exist for them, or at least doesn't matter. But as Masanobu Fukuoka put it, "If we throw Mother Nature out the window, she comes back in the door with a pitchfork," and as we ignore the physical realm, the physical economy (the one that actually keeps people fed and sheltered and moves them about the landscape) shrinks and decays. The inevitable result is more and more of these cyber-campers and their gadgets will drop off the network, shrivel, and die with nary a tweet to signal their demise.

And this is, of course, a shame: a terrible and unnecessary loss to the online community. Yes, resource depletion cannot be turned back, nor can catastrophic climate change. Yes, the global economy will crumble as a result, and people will die. But why should their online personae die with them? That, at least, seems preventable. Not only that, but letting users die is bad for the economy: companies like Facebook, Twitter, Google, and numerous tech start-ups are judged based on the size of their user base. Some of them may not generate much in the way of revenue, but if they have millions of users then everyone assumes they must be worth something. But if the physical economy continues to cave in on itself and their user base starts to drop off like flies in autumn, then that would be bad for a company's valuation and stand in the way of it securing additional rounds of financing. If it finds a way to compensate, then all would be well with their business plan, and their innovative social networking platform might indeed help power the global economy out of the doldrums and into some other nautical metaphor, but if not, then it would be doomed. Doomed! And investors don't like the sound of the word "doomed."

The solution is as obvious as it is counterintuitive, and it comes from a classic of Russian literature: Nikolai Gogol's Dead Souls. It details the exploits of one Chichikov, who rambles around the Russian countryside, visiting estates and convincing their owners to sell to him their dead peasants. With the dead peasants' papers in hand Chichikov is then able to use them as collateral for loans and to mortgage them (omitting to mention, of course, that they are dead). Correspondingly, the solution for the social networking tech start-ups, moving forward, is to leverage their dead users. This, after all, seems like a humane and caring thing to do: why let someone's online persona die with them? This is often a shock to the other users, who most likely have never even met the deceased person in real life, and don't particularly care whether he or she physically exists. It was once said that on the Internet nobody knows whether you are dog; so let it be that nobody knows whether you are even alive. In a society that lavishes hundreds of thousands of dollars on end-of-life medical care, why not save a little of that money for the cyber-afterlife? For people whose lives are mostly lived on the Internet, technology that extends their online persona past their physical death would be life-extending technology par excellence, and a fitting tribute.

The technical challenge is considerable, but it is by no means insurmountable. For example, let's say you have a dead user who likes cats. Now, it is well known that uploading pictures of cats is a good way to get "karma points." In life, our erstwhile cat-lover would have immediately responded with a succinct message such as "UR KITTEH RLY CUTE LOLZ" by thumbing it into some handheld device. After our user's untimely demise, the same function would be performed by a computer program. To paraphrase Descartes, "Txto, ergo sum." Here is a proof of concept that took me just a minute or two to code up:

With a bit of effort this sample code can be extended to cover the typical set of the eternally resting user's online utterances. (Of course, a more contemporary way to implement it would be as a web service. And, of course, it would have to be a RESTful one.)

With a bit of effort this sample code can be extended to cover the typical set of the eternally resting user's online utterances. (Of course, a more contemporary way to implement it would be as a web service. And, of course, it would have to be a RESTful one.)Thus, generating tweets, SMS messages and posting comments, perhaps even generating entire blog posts that convincingly mimic those of a living user is an eminently surmountable technical challenge. But a much harder problem is to keep our dead user in the vanguard of exciting new social movements and fashions that sweep through the net with lightening speed. Just recently "planking" was all the rage.

This is "planking"

This is "planking"But now "planking" is just completely last week and everyone who is cool and hip is into "owling."

This is "owling"Without a timely infusion of such new trends our deceased user's persona would grow stale and unpopular. But perhaps that is as it should be: let the living rise in popularity while the dead slowly become de-friended and de-linked, eventually lapsing into oblivion. After all, all we are doing is buying some time. The last person out, please remember to shut down the cloud, because what would be the use of letting dead people talk to each other?