A Pile of Straw at the Bottom of the Cliff

There is an old Russian saying: "If Ihad known where I would fall, I would have put down some strawthere." ("Знал бы, гдеупаду—соломки бы подостлал.")It is one of thousands of such sayings that are the repository ofancient folk wisdom. Normally, it is used to express the futility ofattempting to anticipate the unexpected. Here, I am using itfacetiously, to underscore the madness of refusing to anticipate theunavoidable.

There is an old Russian saying: "If Ihad known where I would fall, I would have put down some strawthere." ("Знал бы, гдеупаду—соломки бы подостлал.")It is one of thousands of such sayings that are the repository ofancient folk wisdom. Normally, it is used to express the futility ofattempting to anticipate the unexpected. Here, I am using itfacetiously, to underscore the madness of refusing to anticipate theunavoidable.I started thinking along these lineswhen I was invited to speak at the annual conference of ASPO(Association for the Study of Peak Oil), which was held in Washingtonin October of last year. It was shaping up to be something of avictory lap for the Peak Oil movement, now that the moment whenglobal conventional oil production reached its historical peak iswell and truly behind us, while the newer unconventional sources ofliquid fuels have turned out to be insufficiently abundant and toocostly both to the pocketbook and the environment. I wanted to usethis opportunity to try yet again to correct what I see as a majorflaw in the narrative of Peak Oil: the idea of a gentle,geologically-driven decline in oil production, which seems quiteunrealistic, which I had detailed in my article "Peak Oil is History" more than a year before. But I also wanted to look beyondit and sketch out some plans that would work after oil productiondives off a cliff, and what it would take to get them off the ground.

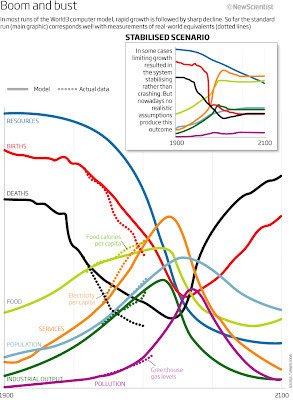

It's all well and good to presentverbal arguments, but words don't stack up against numbers andcurves, so I started looking around for a mathematical model thatwould capture the essence of what I was setting out. I put out a callfor people to contact me if they wanted to collaborate, and was veryhappy to receive an email from Prof. Ugo Bardi of the University ofFlorence, asking what I had in mind. Ugo is an authority on the Club of Rome's much maligned but now vindicated "Limits to Growth" model, having provided it with a recent book-length update.

I wrote back to Ugo:

"I would like to argue that whereasthe method used to model Peak Oil using a Gaussian is reasonable whenlooking at individual oil fields, provinces and countries, it is notreasonable when looking at entire planets, because, unlikeoil-producing provinces and countries in decline, planets can'timport oil, while oil shocks cause industrial economies to collapserather than decline gradually along some geologically constrainedcurve. In [my] article ["Peak Oil is History"] I have a long list of effects such as EROEIdecline, export land effect, etc., to make the case for a stepwisedecline rather than a gradual one.

"If we take our nicesimple Gaussian model of Peak Oil and zoom out sufficiently far, itlooks like an impulse. The peak amplitude and the width are not sointeresting; but we do know what the area under the curve is: theultimate recoverable. This is the "Odulvai Gorge" view ofPeak Oil. Zooming back in, we see that the leading edge is the"growth" edge, influenced by economic growth, technologicalimprovement, ever-wider exploration and so on, and we expect and seeexponential growth. The trailing edge, on the other hand, dominatedby the sudden collapse of industrial economies, due to all thefactors I listed, would be expected to resemble exponential decay,but is so steep that we might as well approximate it as a stepfunction. This is what we generally see when a growth process reachesa limit. Beer-making is one popular example: yeast population andsugar-use increases exponentially, then crashes.

"As oil is the "enabling"energy source, which makes it possible to deplete all other resourcesat a high rate, a stepwise decline in the availability of oil wouldhalt the process of depleting (almost) all other resources (firewoodin rural areas and a few others are the exceptions). So, the furtherthe collapse is delayed, the less there will be left to start overwith, making any attempt to prolong the oil age quite unhelpful. Thisis an ecological argument: the greater the overshoot, the more theeventual carrying capacity is reduced. Therefore, investing in"collapse-proof" schemes and businesses is harmful.

"An alternative is to set resourcesaside (supplies, tools and equipment, designs, skill sets) that canbe rapidly deployed once collapse occurs. Entire turnkey businessschemes can be developed and capitalized, in expectation of collapse.These would 1. hasten collapse by withdrawing resources from thepre-collapse economy (a net positive) and 2. provide for rapiddevelopment of viable post-collapse businesses, such as manual,organic agriculture, sail-based and other non-motorized transport,and so on (also a net positive). Seeing as there is already adistinct lack of good ways to invest money (US "suprime"Treasuries? Gold bullion? African drought-stricken farmland?) thiscan be presented to the investment community as a way to hedgeagainst collapse."

Ugo wrote back:

"Hmmm.... let me see if I understandyour point: you say that a Gaussian is no good; that the descent onthe "other side" of the peak should be much faster than thegrowth. Am I right?

"If so, it is curious that I was workingright on this concept today - and I think I cracked the problem justone hour ago!! Maybe it was already obvious to other people, but itwasn't to me; maybe I am not so smart but, at least I am happy, now.So, I can tell you that you are right on the basis of my systemdynamics model. Descent IS much faster than ascent!!

"When Ireceived your message I was just starting to prepare a post for myblog "Cassandra's legacy" on this subject. So, if you canwait a couple of days, I am going to complete my post and publish it.Then you may give a look to it and we can discuss the matter more indepth. And I'll make sure to cite your post, because I think it isright on target."

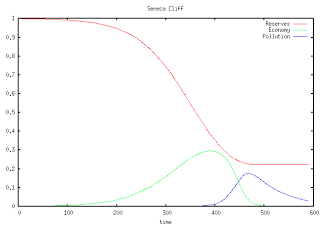

A little while later Ugo published his"SenecaCliff" post. The name came from the following quote fromSeneca:

"It would be some consolation for thefeebleness of our selves and our works if all things should perish asslowly as they come into being; but as it is, increases are ofsluggish growth, but the way to ruin is rapid." LuciusAnneaus Seneca, Letters to Lucilius, n. 91

I wrote back:

"The Seneca Effect is splendid, andwell-named. (Last winter I re-read Seneca's letters to Lucillus whilelaid up with the flu, and found a lot that's relevant.) I think Ishould be able to build on this model to include a few othereffects."

Ugo's post detailed two very simplemodels.

The first model reproduces thecanonical depletion curve, which looks like a Gaussian. It is basedon just a couple of intuitively obvious relationships: firstly, therate at which the resource base is exploited is proportional to boththe size of the resource base and the size of the economy that isbeing used to exploit it; secondly, the economy decays over time(depreciation, entropy, etc.) Set up the initial conditions, run theclock, and out comes the expected curve.

The second model incorporates the ideaof pollution, or bureaucracy, or overhead: the inevitable externalcosts of exploiting the resource. About a third of the flow isdiverted into the pollution bucket, which also decays over time. Thefirst model, it turns out, must be filling the "pollution" bucketby exploiting some other resource, through imports. But since theplanet as a whole imports nothing, the first model is not relevant tomodeling global Peak Oil, and so we have to use the second modelinstead.

I found the Seneca Cliff model veryeasy to reproduce, first using a spreadsheet, then by writing a shortprogram in Python:

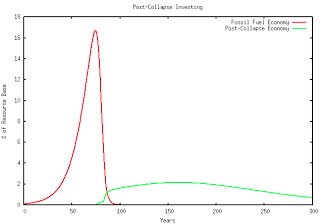

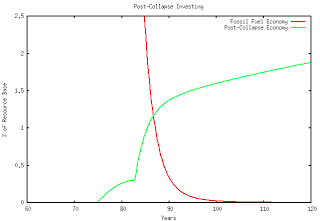

I showed my results to Ugo, and hewrote back: "Yes, it seems to be working." I then started addingelements to this model, to see what it might take to "reboot" theeconomy into a post-fossil-fuel, post-industrial "operatingsystem." I made a highly idealized, wildly optimistic assumption: when a criticalmass of people realizes that global Peak Oil has occurred and thatthe global economy is beginning to crash with no hopes of recovery,they will do the right thing: take 10% of the remaining industrialoutput, divert it and stockpile it, to be used to "reboot" into apost-industrial mode once the crash has largely run its course.

There is a problem with this plan: to alayman, global Peak Oil is rather hard to detect, leading to muchconfusion and dithering. Up to the final crash, it looks like aplateau, where oil production refuses to increase in spite ofhistorically high prices.

But ignoring this issue (you have toidealize somewhat, for the sake of clarity, when working withconceptual models), if we start setting aside a "Peak Oil Tithy"around when Peak Oil occurs, and if we deploy all that we'vestockpiled when the fossil fuel economy can no longer support us, thepicture looks like this:

Zooming in, there are two triggers: when the "tithy" starts accumulating (shortly after thepeak), and when it is deployed to build a post-collapse economy (whenthe fossil fuel economy is 50% down from its peak).

The resulting post-collapse economy isquite a lot smaller than the fossil fuel economy, but still largeenough to support a significant portion of the current population,albeit at a much lower standard of living. There might not be indoorheat or hot water, certainly no tropical vacations in wintertime orfruit out of season, no advanced medical treatment and so forth. Butit would still be better than the alternative, or, rather, thecomplete lack thereof.

I presented these graphs at the ASPOconference, where they were greeted with polite silence. There weresome "investors" at the conference, but they were busy attendinga session dedicated to discussing opportunities to invest in thefossil fuel economy. Nobody offered any counterarguments, but thennobody felt compelled to act based on what I said either. Why do youthink that is? Why is that reasonably rational individuals who areable to follow an argument and who are unable to refute it are at thesame time incapable of making the transition from thought to action?What is stopping them? Humans are clearly smarter than yeast, whatdoes that matter if they are incapable of acting any moreintelligently? I will attempt to address this question in asubsequent post.

Published on February 26, 2012 10:18

No comments have been added yet.

Dmitry Orlov's Blog

- Dmitry Orlov's profile

- 48 followers

Dmitry Orlov isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.