Will Buckingham's Blog, page 29

November 4, 2012

Giveaway!

I'll be sending out the winner's copies on Monday. Commiserations if you didn't win, but for those of you who have put the book on your "to read" lists, I hope that you enjoy it.

With all best wishes,

Will

October 31, 2012

The Descent of the Lyre review on thebookbag.co.uk

There’s a wonderful new five star review of The Descent of the Lyre up on book review website, theBookBag.co.uk.

“Seasoned with knowledge of philosophy and storytelling as well as a deft touch and lyrical beauty,” they say, “it feels totally original.”

You can read the full review here, and if you are convinced, you can buy a copy of the book.

October 25, 2012

Utopia etc.

Utopia, edited by Ross Bradshaw

Utopia, edited by Ross Bradshaw

I was very pleased this morning to receive my contributor’s copy to the Five Leaves anthology on Utopia, a wonderful collection of essays on utopias, dystopias and everything in between, edited by Ross Bradshaw. You can get your copy from Inpress books. My own contribution is called ‘The Trouble with Happiness’ and is a more extended philosophical riff on the tale I alluded to in my Introducing Happiness book, an encounter with the happiest man alive whilst working on a happiness research project in the city of Birmingham.

Do get hold of a copy of the book, or order it for your library, for tales of utopias from the local pub to Paraguay, from Wales to New Zealand, and from the graveyard of Moravia to the Big Rock Candy Mountain.

October 23, 2012

Boredom, Flow and the Eggs of Experience

Image from The Book of Animals of al-Jahiz, Syria, 14th century. Arabian Ostrich. Wikimedia Commons.

Image from The Book of Animals of al-Jahiz, Syria, 14th century. Arabian Ostrich. Wikimedia Commons.

Over the last couple of weeks, I’ve been engaged in the perhaps thankless task of trying to persuade my students of the virtues of boredom. This is not simply a way of finding an excuse for my occasional tendency to digress and head off on rambling philosophical excursions. It is instead something that is born out of my conviction that boredom is rather more important, and more central to the processes of learning, thinking and creation, than some might often like to admit.

One of my all-time favourite essays is Walter Benjamin’s essay on Leskov, ‘The Storyteller’, where he talks about the craft of weaving experience into stories and tales. It is in this essay that Benjamin makes the wonderful claim that boredom is the ‘dream bird that hatches the egg of experience.’ None of us who are alive, here in the world, lack in experience. But experience alone is not enough. It needs a certain kind of incubation if experience is to hatch into something interesting and new: a new thought, a story, an idea, a new possibility. You need to sit on those eggs, to cluck over them, to keep them warm. They will hatch (if they hatch at all) in their own good time. The process cannot be forced. But they won’t hatch without being willing to sit on them for as long as it takes.

I think that this is true of many things. Many of the books I have loved most have involved periods of boredom whilst reading them. Many of the things that matter most to me, that have become well-woven into the fabric of my life, matter because I have been willing to sit with boredom until I come out the other side. As a long-time (although admittedly, these days, patchy) practitioner of Buddhist meditation, I know that boredom is simply a part of the fabric of life, a part of what it means to be human. It is not necessarily a sign that something is particularly wrong. It is not a symptom. It is something that comes and goes. When I first read Husserl, when I learned to play the guitar, as I have ploughed through fairly mindless writing drills in an attempt to crack the craziness that is the Chinese writing system, whilst I have tried and tried again to put together ideas for the next book… at all these times, I have found that boredom has been a part of the experience.

These days, I’m less troubled by boredom than I used to be. If you sit in meditation for long enough, your mind becomes bored of boredom and starts paying attention again. If you work and rework that difficult chapter of the book that you can’t get right, returning to it again and again like a fretful and broody hen, then at last one of those eggs hatches, and you have something new and surprising on your hands. If you keep on reading that difficult book, eventually you may experience some sudden illumination or delight. Or, as Kafka one wrote, if you remain sitting at your table and listen, or if you do not even listen but simply wait, quiet and still and solitary, then the world will freely offer itself to you to be unmasked, and will roll in ecstasy at your feet. Because it has no choice.

At the moment, there is a fashion for the idea that everything we do should somehow provide us with delight, that we should exist as much as possible in that mystical state known as ‘flow’, that thin line (or broad path?) between frustration on the one hand and boredom on the other, and if we don’t manage this, somehow we are not doing it right. This, it seems to me, is not just wrong, it is also a recipe for disappointment. Flow, if and when it happens, is all very well if what you are doing is a good and useful thing to do. But boredom and frustration are fine too, as long as you don’t let them derail you.

My own view, when it comes to writing (or to meditation for that matter), is this: that in the end the work is the thing, the keeping on keeping on, the willingness to sit on those eggs as long as it takes, through boredom and frustration and, yes, perhaps even flow, until you hear the little tap-tap-tap of something inside your eggs, waiting to get out, at which point the work struggles to its own feet, and lets out a little, bewildered cheep!

October 18, 2012

Bishop’s Snorghford?

It’s very nice to see that The Snorgh and the Sailor has been shortlisted for the Bishop’s Stortford Picture Book award. It’s on a shortlist of nine picture books, some of which I’m familiar with, and some of which I’m looking forward to reading.

The award will be made at the Bishop’s Stortford Literature Festival in February 2013, and it will be judged by the toughest of audiences: a popular vote amongst students from participating schools.

Find out more about the award here.

October 17, 2012

On Radio Bulgaria

The other week I had a fun phone call to Sofia, Bulgaria, where I chatted to Rossitsa Petcova about my novel, The Descent of the Lyre. Radio Bulgaria have now published the interview online, and you can have a listen by clicking here. Get yourself a cup of tea before the broadcast starts, as it’s a good half hour; but they’ve done a lovely job splicing together the readings, interview and some particularly wonderful Bulgarian music.

October 11, 2012

Mo Yan, Politics and Writing

Life and Death Are Wearing Me Out, by Mo Yan

Life and Death Are Wearing Me Out, by Mo Yan

Having heard this afternoon that Chinese novelist Mo Yan 莫言 had won the Nobel Prize, I thought that I would track down some of his work to have a quick read. I only know Mo Yan indirectly, through the film Red Sorghum, which was based upon one of his books, and for which he sold the rights for £80. This seemed not very much to go on, so by a bit of judicious rooting around online I managed to dig out a copy of his short story Soaring (翱翔) in both English and Chinese; and having picked my way through the story in the original, and then read it in English, I have to say that I was very impressed. It was an old-fashioned tale of village brutality combined with uncanny, unearthly happenings, the latter very much after the model of Mo Yan’s forebear in his home province of Shandong, the strange and wonderful seventeenth-to-eighteenth century writer Pu Songling. The Nobel Committee called it “hallucinatory realism”, and it seems a fitting name for the genre.

There has, of course, already been a degree of controversy over the prize: Mo Yan, some have claimed, is not political enough. I wonder about this. I wonder what it says about our perhaps impoverished notion of what ‘politics’ means, as well as of what literature is about, and what writers (in particular Chinese writers) do, or should do. In the West, we prefer our Chinese writers and artists, it sometimes seems, to be firebrands who rage against, or pointedly pour scorn upon, the regime in Beijing. It fits a comfortable Western stereotype and, at the same time, makes us feel better about ourselves. Yet whilst there is, no doubt, a great deal to rage about in China, for all this, I would like to make a plea for a broader view of literature and the politics of writing.

Closer to home, I am conscious that, when it comes to writing fiction, I have very little to say, in any direct fashion, about the gang of ideologically driven hoodlums who constitute the current government of the United Kingdom. It is not that, when it comes down to it, I don’t really mind the considerable violence that is being done to many of those things that I think are worthwhile about country in which I live. I do mind. I mind so intensely that sometimes I really don’t know what to do with myself. But at the same time, I am aware that I cannot fully choose my compulsions as a writer. There are many things that can be done to try and make the world in which one lives, or the corner of it in which one lives, a better, kinder and fuller place. There are perhaps even a many things that can be done as a writer to make the world a better, kinder and fuller place. Not all of them involve ‘politics’ in the way that the term might be understood by the journalists. As Mo Yan himself said recently at the London Book Fair, ‘Of course I care about politics, and I write about things that I see that I think are wrong – but I also think that the writer should not just be a political activist, a writer should be a writer, first and foremost.’ One can argue about the ‘should’ in this sentence (why not be a political activist first, and a writer second?); but the point is well-made nevertheless.

So, what to make of the Nobel Prize for Mo Yan? I am, at root, sceptical about literary prizes. I believe in a varied and diverse literary ecosystem, and the notion of the ‘best book’ or ‘best writer’ is one that, pushed to its limit, threatens to obscure the fact that different books and different writers do very different things. Literary prizes can be like the stupid playground game of questioning, ‘which is better: a camel or a giraffe? A nightingale or a vulture? Murakami or Mo Yan?’ And, of course, the awarding of prizes, like the writing of books, is always a political act, in the broader sense of the term. But, putting this aside, I’m just pleased to have had my attention drawn to a writer whose strangeness—whose hallucinatory realism, perhaps—may open further doors (as the work of new-found writers often does for a reader) onto the possibilities that literature offers. And—who knows?—perhaps Mo Yan may provide me with new ways of thinking, seeing and acting that help as I struggle with the broader condition of hallucinatory realism in which I feel I am enmeshed, whenever I turn on the news.

October 9, 2012

Existential Romps with Short Men

It’s now five years since my first novel, Cargo Fever, was published; and—now that my second novel has emerged out into the world—I can perhaps confess that the earlier book is one towards which I harbour both a kind of affection and also a kind of ambivalence. Affection, because I still love the characters, the setting, the strangeness of it all; and ambivalence, because I am still not sure how the book managed to find itself marketed, mistakenly I think, as an adventure yarn à la Wilbur Smith, when I’d always intended it to be more of an existential romp. But there is no shelf in the bookstore marked ‘existential romps’ (although if there were, the world, I feel, would be a better place), and so it has continued to sit on the shelves a little uneasily.

It’s now five years since my first novel, Cargo Fever, was published; and—now that my second novel has emerged out into the world—I can perhaps confess that the earlier book is one towards which I harbour both a kind of affection and also a kind of ambivalence. Affection, because I still love the characters, the setting, the strangeness of it all; and ambivalence, because I am still not sure how the book managed to find itself marketed, mistakenly I think, as an adventure yarn à la Wilbur Smith, when I’d always intended it to be more of an existential romp. But there is no shelf in the bookstore marked ‘existential romps’ (although if there were, the world, I feel, would be a better place), and so it has continued to sit on the shelves a little uneasily.

But what—you might ask—is an existential romp? The romp part is straightforward enough: what I am still very fond of about the book is its friskiness and exuberance. Cargo Fever was about a series of encounters with a badly-behaved (but, I still maintain, essentially benign) orang pendek, or ‘short man’, the forest-dwelling almost-human creature famous from Indonesian legend; and there is perhaps a thread of connection between the diminutive anti-hero of the book (who is only barely glimpsed throughout) and those creatures of Greek legend, the trickster satyrs who spent their days romping in the most shameless fashion on the hillsides, far from the gaze of towns and cities. The existential part is perhaps harder to discern, but when I started out on the book, I was intrigued by questions about the limits of what it is to be human. The Indonesian characters in the book are surrounded by almost-human and not-quite human beings: animals, gods, spirits, Westerners, ancestors; and I was intrigued by how my characters might—as the scholars would perhaps say—negotiate these boundaries. But ‘existential’ is such a heavy, leaden term and, being convinced that heaviness is an aesthetic choice rather than anything else, I wanted to play around with these questions in a much lighter fashion. As a satyr might, rather than as a scholar might.

Anyway, I was reminded of all of these questions and thoughts a couple of months ago, when I unexpectedly ran into Homo floresiensis in the Stockholm museum of Natural History, whilst I was over in Sweden in the summer. Homo floresiensis is the real-life counterpart of my orang pendek, one of the most astonishing scientific discoveries of the past decade. It was only when I was putting together the final draft of Cargo Fever back in 2004, in a cave at Liang Bua in Flores, Indonesia, they discovered the remains of what seemed, back then, to be a species of the genus Homo uncannily similar to the creatures of Indonesian legend.

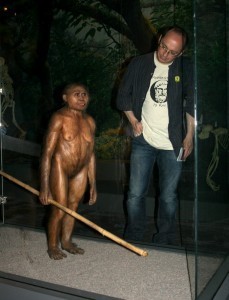

The finds in Liang Bua have led to several years of debate. Now that the arguments have gone to and fro enough to wear themselves out, the scientific consensus now seems to be that, up to at least twelve thousand years ago in Indonesia, there was indeed another species of human in the forests of Indonesia, one that was uncannily like the creatures talked about in these legends. Here’s an image (click for full size) of me communing with the reconstruction of the orang pendek in Stockholm (where, to an averagely tall and averagely short British male, the locals seem almost like another species themselves, orang tinggi perhaps…).

Communing with Homo floresiensis in Stockholm. Photo, Elee Kirk.

Communing with Homo floresiensis in Stockholm. Photo, Elee Kirk.

There was something that I found strangely moving about coming face to face with my first orang pendek over there in Stockholm — sorry, I should say my first Homo floresiensis: a sense of kinship, a sense that my own categories were being called into question. We often see ‘human’ as something that is neatly and tidily bounded, as something that is set apart from other categories. But here, as everywhere, the boundaries are really less clear than we would like to imagine.

I continue to be intrigued by those legends from Indonesia. Now we know with at least some certainty that Homo floresiensis lived in parts of Indonesia, I wonder when the last of these our cousins died out. Twelve thousand years ago? Or more recently, perhaps? How long might small communities have held on? And even if we are talking about ten thousand years or more (five hundred generations, perhaps—not so much, when you think about it), how long might stories endure, passed down from generation to generation, stories that bear the memory of other beings who are, we might claim, not quite human, but at the same time, not quite other to us. And I still wonder what it might do to our philosophies (not to mention our theologies!) and our ideas of what it might be to be human, if we were really to think through the implications of our being only one branch of a broader family. Cargo Fever began with a quote from Saint Augustine’s City of God: ‘There are accounts in pagan history of certain monstrous races of men… These accounts may be completely worthless. But if such peoples exist, then either they are not human; or, if human, they are descended from Adam.’ Now that we know that such peoples indeed existed (not to mention all of our other, better known, cousins), the question of what we do with this knowledge is still one that many philosophers have perhaps not sufficiently got to grips with.

You can get a copy of Cargo Fever here.

UK Literacy Association Book Award

Just a quick post to say that I’m delighted to hear that The Snorgh and the Sailor has been long-listed for the UK Literacy Association Book Award.

Read the full announcement and download the long-list here. The shortlist will be drawn up in early 2013, and the award will be announced on July 5th 2013.

October 3, 2012

The Descent of the Lyre: Giveaway on GoodReads

Just a very quick post to let you know that I have two copies of The Descent of the Lyre to give away on GoodReads.com. All you need to do is to click the link below, and—if you are not already a member of GoodReads—sign up for a free account. The Giveaway is open to readers from the UK, most of Europe, the USA and Canada. The book is to be released in the USA on the 11th December, so if you are over that side of the water, this is your chance to get yourself an sneak preview.

Goodreads Book Giveaway

The Descent of the Lyre

by Will Buckingham

Giveaway ends November 04, 2012.

See the giveaway details

at Goodreads.

Will Buckingham's Blog

- Will Buckingham's profile

- 181 followers