Will Buckingham's Blog, page 31

September 3, 2012

New Review on PIR Online

Just a quick update to say that my review of Simon Critchley’s How to Stop Living and Start Worrying has just been published by Philosophy in Review. The link is HERE.

August 28, 2012

Genre, old-school storytelling, and voice

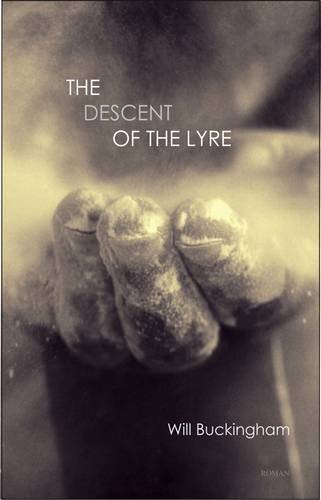

My second novel, The Descent of the Lyre, is due out in the next couple of weeks, and although I have not yet received my final author copies, I am experiencing that familiar mixture of trepidation and excitement that comes in the period before a book flies the nest and makes its way in the world. The book so far has had some very favourable pre-press: it was one of the Bookseller‘s recommended reads for August, and it has also got a slot in August’s Booktime magazine; so I wait to see how it does more widely after those handsome hardback copies (paperback edition to follow in due course, as well as e-book versions, and other formats not yet even dreamt of…) have made their way out into the world.

My second novel, The Descent of the Lyre, is due out in the next couple of weeks, and although I have not yet received my final author copies, I am experiencing that familiar mixture of trepidation and excitement that comes in the period before a book flies the nest and makes its way in the world. The book so far has had some very favourable pre-press: it was one of the Bookseller‘s recommended reads for August, and it has also got a slot in August’s Booktime magazine; so I wait to see how it does more widely after those handsome hardback copies (paperback edition to follow in due course, as well as e-book versions, and other formats not yet even dreamt of…) have made their way out into the world.

Only now that I see some of the pre-release feedback do I realise that what I have written in the Lyre is, in a certain fashion, historical fiction. This really shouldn’t surprise me at all, given that it is a book that is set firmly in the nineteenth century in Bulgaria and Paris: if not historical fiction, then what else could it be? Nevertheless, when I first saw the book described as ‘historical fiction’, I found myself thinking, ‘Oh, how strange—so that’s what it is…’

As a writer, genre is something I don’t think about very much at all. There are writers who have a clear sense of genre, and there is no doubt that this robust sense of how one’s work fits in to the marketplace can be useful, but I’m just not that kind of writer. I don’t tend to have a clear idea of what I am doing until I have done it. In the world of writing punditry, that clamour of advice for writers and would-be writers, there are those who claim that a clear sense of audience and genre are absolutely necessary, whilst there are those who claim that these things are not necessary at all; but I’m a bit sceptical of all these imperatives. I’m in favour of a kind of literary mixed ecology where people write to different ends and different purposes, where they go about writing in different ways. It’s a wide world, and there’s room for more than one approach.

But, to get back to historical fiction, I wonder if the reason that I was surprised that this is the genre the book has found its way into is that this wasn’t written as historical fiction in the realist mode, in that it doesn’t attempt to recreate an era or offer a window onto the past as it actually happened. Part of the reason for this is that the story draws not just on history but also on myth; and part of the reason is that of voice. One thing that I am always conscious of in writing is that what I am doing is telling a story. I am not providing a window onto reality, but I am spinning a yarn. And like any oral storyteller, I have the habit of occasionally breaking the apparently realist spell, if it becomes a little too realist, to remind the reader that this is, after all, an act of storytelling. ‘Oh, look…,’ I say at certain points, ‘this is a story’.

Some will no doubt disapprove; but I have always had a weakness for stories in which there is a clear storytelling voice that doesn’t quite belong to the story itself, that stands at a little remove from the story, that is not entirely involved, somewhat philosophical, a little bit wry, occasionally digressive. And whilst these things might seem to some like strange postmodern voodoo, I prefer to think of this approach as old-school storytelling in which the storyteller’s voice is a part of the story. Realism in storytelling is, after all, only a very recent invention (or, I would say, only a very recent myth…).

August 18, 2012

In Praise of the Moomins

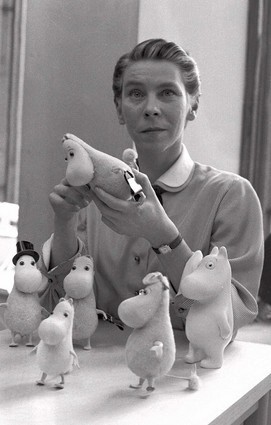

Tove Jansson, 1956: Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Tove Jansson, 1956: Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

I am writing this somewhere on the ferry between Stockholm and Turku; and as I look out of the window at the grey sea and the rocky little outcrops of Åland, I find it all seems strangely familiar, as if I have seen it somewhere before. And, in a way, I have; because these are the seas that I navigated again and again in my childhood imagination, in the company of Moominpappa and Moomintroll and Snufkin, whilst reading those incomparably strange and wonderful children’s books by Tove Jansson.

These are the seas with islands so small and remote and strange that they might seem like bits of fly-dirt on the map; seas where chilly and lonely Grokes pursue distant boats with paraffin lamps at the head of the mast, glowing in the night; tiny harbours where small, solitary creatures crawl secretly underneath the tarpaulins of tied-up boats, to fall asleep and dream. And it feels like a pilgrimage of sorts to come here, and to watch out at the cormorants scudding over the waves, and to look across the countless islands towards the distant horizon.

These days, the Moomin characters have turned into a global franchise; and yet when I think about my own relationship with these books that were so formative of my imagination, I realise that what I owe these books is something much more private and intimate, a philosophy of sorts. Because in Tove Jansson’s books, when I re-read them now, I find a fierce recognition of the importance of solitude; an expansive sense of friendship—not a friendship that erases solitude, but one that is a kind of mutual recognition within it; a sense of delight in the world, its seasons and its changes, that doesn’t require any form of transcendence; and a hospitable generosity of spirit that manages, in one way or another, to accommodate even the most awkward and tricky of characters—not just eccentrics, stove-dwelling ancestors, hemulens, free spirits and oddballs, but also genuinely alarming creatures such as grokes and philosophers. And so I am happy to confess that my Snorgh would not be the Snorgh that he is without Tove Jansson; but, more than that, I suspect that perhaps my entire sense of life, my general philosophical orientation, would not be quite what it now is, had I not fallen under the spell of those extraordinary books…

An Island on the Way to Finland (clickable). Photo courtesy of Elee Kirk

An Island on the Way to Finland (clickable). Photo courtesy of Elee Kirk

August 15, 2012

Techno-utopians, luddites, paper-fetishists and others

Saint Jerome with his books, from the Nuremberg Chronicle. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Saint Jerome with his books, from the Nuremberg Chronicle. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

When it comes to technology, I suppose that I was an early adopter. Back when I was at school, aged ten, I injured my left hand, which was as a result put into a sling. It was a small school, with no more than forty or fifty pupils, in the village of Great Snoring in Norfolk. Great Snoring was just down the road from Little Snoring, where a family called Gotobed lived. Norfolk was like that in those days. Anyway, there I was, one-handed and incapable of writing, and the school had a problem on their hands. As it happened, however, the school had just bought a Sinclair ZX81 computer; and so whilst my hand healed up, I was put in charge of working out how the strange little black box worked. In those few weeks, I learned how to write programs in Sinclair’s version of BASIC, and I was immediately fascinated by what this curious little machine could do, if you fed in the right instructions.

Since then, my life has—as with many of my generation—unfolded in symbiosis with an astonishing array of computers, variously bleeping and squeaking electronic devices, and calculating machines that would make Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace gape in wonder. And although it is possible to forget this wonder, sometimes I look at my Macbook on the desk in front of me, and am astonished by what it can do, and by how much I take it for granted. What an astounding beast this thing is, this machine that can allow me to write these words and broadcast them to the world, that can play music and draw pictures and perform calculations and send messages to Beijing or Boston or Bulgaria, that can store libraries of research papers, multiple drafts of novels.

I am, in other words, not exactly a Luddite; but neither do I subscribe to what is often called techno-utopianism. So I do not think that technology is an inherent evil, I do not wish to return to some purer, technology-free age in the past—or, for that matter, in the future. On the other hand, I do not think that the world will be saved by the internet, or by developments in technology. Outside of a religious conception in which the world is fallen and in need of saving, I’m not sure that the notion of ‘saving the world’ is one that makes much sense, anyway: and it seems to me that techno-utopians, like many utopians more generally, have a religious kind of zeal in their promises of the Kingdom to come.

In the world of books, over the past five years or so, there have been great outbursts of Luddism and techno-utopianism, each of them feeding off the other. The Luddites, the paper-fetishists and manuscript-sniffers, claim that all value lies in the printed page, in the mystery of ink on paper made from wood-pulp, in the physical object that is the book. Meanwhile, the starry-eyed techno-utopians happily download their books to their e-readers, or if they are unlucky enough to fall into possession of paper copies, they immediately slice them up, run them through the scanner, and enjoy them in electronic format. The techno-utopians pour scorn onto those atavistic paper-based readers who belong only to the past, lugging around hefty tomes as they, who belong to the future, tote their super-portable e-readers. ‘The paper book is dead!’ they cry. In response, the Luddites, believing that they are guardians of a deep, spiritual culture that is under threat, and gazing at those remnants of sliced-up book in the recycling bin, cry out in response: ‘If so, then culture is dead!’

It seems to me, however, that both camps overstate their own case, and that both camps fetishise the technologies that they favour: because a book, written in ink on paper, is no less a technology than is an iPad or an e-reader. The paper book is a particular kind of technology, just as the electronic book—and the device upon which it is read—is a particular kind of technology, and these technologies are physical things in the world. Remembering the physicality of technology is important, I think, as a way of rebalancing the debate. Books, for example, are not mere information. Insofar as they are information, they are information that is reflected in, and related to, particular kinds of configurations of stuff in the world, stuff that acts as a kind of bearer or medium for that information. Literature, the Chinese critic Liu Xie said around the turn of the sixth century, is about pattern. But literature is also patterned stuff: whether the vibration of the air that are sound as a poem is recited, or marks on a page, or dots on a screen. And the stuff-ness of this patterning is important. Materiality, or matter, matters. It matters, for example, because it allows us to ask broader questions about the technologies we use to communicate with each other, or the technologies we use to store information: about freedom, about political and economic control, about how we read and how we relate to what we read.

I am not skilled in the arts of haruspication. It is just over thirty years since I first pressed the keys of that little ZX81, and so much has changed: so I would hesitate to guess what what the world will look like in another thirty years’ time. But I would prefer it if the debate could move beyond nostalgia for the papery past and cheerleeding for the digital future. It would prefer it if we could all recognise that we live, at least for now, in an age of mixed technologies, which are used to different ends, which are perhaps differently useful and differently inconvenient, differently emancipatory and differently fraught with problems.

Incidentally, my next novel is due out in hardback in a couple of weeks. Tehcno-utopians, who won’t like the book anyway, because it is set in the past (and who cares about the past?) will be able to get hold of a copy when the e-book comes out next year. It’s the future, don’t you know…

August 9, 2012

The Snorgh and the Sailor in Leicester Central Library

Just a quick update to say that I’ll be reading today from The Snorgh and the Sailor at Leicester Central Library this afternoon. The time is 2pm – 3pm, and there will be various fun activities scheduled along the way as well.

August 4, 2012

Lowering the Bar

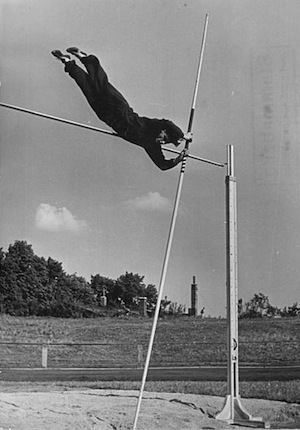

Wikimedia Commons: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-19650-0017 / CC-BY-SA

Wikimedia Commons: Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-19650-0017 / CC-BY-SA

If there is one thing that seems almost impossible to escape these days, it is the notion of excellence. As a little demonstration of our contemporary obsession with excellence, try this as an experiment: go to the website of any university and type in the term ‘excellence’. Note down the number of search results. Now type in any particular virtue that you favour, ‘curiosity’, for example, or (don’t say it too loud) ‘wisdom’, and compare your results.

It is clear from little experiments such as this that universities are excessively concerned with being excellent. And this is not just a concern of universities. Everywhere—from the halls of power down to primary school classroom—we hear the language of excellence. Teaching, we are told by government ministers, must be excellent; writers the critics say, must be excellent; and I probably don’t need to remind anybody in the UK that the Olympics in full swing, and that the second of the three so-called ‘Olympic values’ is also ‘excellence’ (along with ‘friendship’ and ‘respect’, apparently).

It seems to me that the term ‘excellence’ is so widespread that it risks becoming entirely empty of meaning; and I can’t help but wonder about this hyper-inflation of rhetoric that demands excellence on all fronts. Thinking about the notion of ‘excellence’, I have to confess that, in the end, it is simply not something I aspire to. So when it comes to writing, I don’t aspire to ‘excellent’ writing; instead I aspire to writing stuff that is interesting (to me, of course, and—I hope—to however many readers eventually stumble across what it is I have written), writing that pursues a set of questions, ideas and images with a kind of sustained determination, writing that weaves intriguing stories and fables. When I write philosophy, I don’t aim to produce ‘excellent’ philosophy—what would that be, I wonder?—but instead I’m interested in opening up interesting questions and reflecting more deeply upon these questions. When I teach, I have no interest in excellence in teaching. I am interested, instead, in teaching that is friendly, and stimulating, and sometimes a bit mad and digressive; I’m interested in communicating, as a human being and as best I can, with the other human beings with whom I have the good fortune to be sharing a teaching room.

It could be argued that all these things are constitutive of ‘excellence’; but there are problems with this. Firstly, it is clear that these various aims and aspirations that I have are not always fulfilled: sometimes I write stuff that just doesn’t quite work; sometimes I put out philosophical arguments that are as full of holes as a Swiss cheese; sometimes I get to the end of a lecture and I think, ‘Well, that was really not my greatest performance.’ You can’t be excellent all the time: and anybody who thinks that you can is simply deluded. Human life is not like that. Nor can you be excellent in all domains simultaneously. People who think that they are, who have no sense of their own shortcomings, are at risk of becoming a dangerous liability.

But more than this, things like writing and teaching involve risk—any creative activity does—and there is thus always the possibility that things won’t work out. I sometimes tell my writing students that they should take risks with their work. Sometimes they say, ‘Will I get a better grade if I do?’ And I have to say, ‘Potentially, yes… although, then again, your final grade might also be worse. But who wants to spend their life playing it safe?’ Because that’s what risk means.

When I hear somebody say ‘excellence’, I not sure that any of the things that matter about what I do are really captured by the term. ‘Excellence’ is one of those terms that tends to level out what matters into bland sloganeering; and I find myself wondering about the sheer unkindness of all of this fretting over excellence. The standards to which we hold ourselves and others are often brutally high. It was the poet William Stafford, I think, who said somewhere (and I am quoting from my less-than-excellent memory) that as writers we must be able to write without feeling that we have to write like Shakespeare or Milton. It is, I have always thought, wise and liberating advice. I have long thought that this is the case not only in writing, but also elsewhere. When I go to the doctor, I don’t want excellence. I want the doctor to do a good enough job. When I encounter people in daily life, I don’t want them to behave excellently towards me, although I’d prefer it if we could more or less get by, in a stumbling, more-or-less good-natured ad hoc fashion.

What I’m saying, then, is this: I’m in favour of lowering the bar. I’m in favour of lowering the moral bar, the literary bar, the pedagogical bar—the whole lot, across the board. I’m in favour of giving up on the nonsense idea of the perpetual pursuit of comprehensive excellence, an idea that always strikes me as exceptionally harsh, for something more sensibly and practicably human—for the notion that good enough is perhaps good enough.

July 24, 2012

Chinese and Bagpipe Music

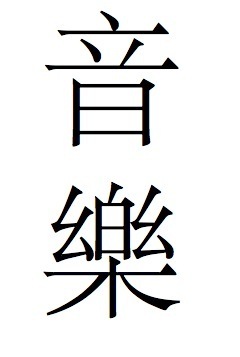

“Music” — yīnyuè

“Music” — yīnyuè

As many who know me will be aware, I’ve spent a good deal of the last three or four years trying to make some inroads into the Chinese language. This is, in part, related to my various research interests, and in part related to the book I’ve been working on exploring the Yijing, or Chinese Book of Changes, as a kind of Calvino-style literature machine. And although progress has been perhaps a little slow, Chinese being—as China scholar David Moser once famously pointed out—damn hard, I’m fairly happy overall with how it has all been going. I’m terribly rusty on conversation, to be sure—living here in the UK, I don’t have as much practice as I would like—and my reading ability goes up and down, but I can pick my way through academic articles in Chinese, at least on a good day, or if I do it in the morning when my mind is fresh; and I’m finding the experience of getting to grips with Chinese immensely fruitful. And, more to the point, fun.

I’ve been thinking a bit about the processes of moving between languages recently, in part because I am deeply immersed at the moment in Douglas Hofstadter’s wonderful book on language, music, translation, learning, cognition and—well, and almost everything else—Le Ton Beau de Marot: In Praise of the Music of Language (a book where the above-mentioned David Moser makes several appearances, incidentally). Hofstadter—a polyglot who claims, however, to only speak around π languages, which is to say, 3.14159 or so—is wonderful on the complexities and puzzles presented by the notion of translation, by the attempt to move from one language to another. And it struck me reading this book on the music of language that my Chinese has perhaps always been lacking in that distinctive ‘music’ of Chinese-ness. As the Chinese friend who I meet up with weekly, and who patiently corrects my mistakes, said some time ago, there has always been something weirdly non-natural, something weirdly foreign-sounding about the way I was speaking: the tones may have been right (more or less), the sounds may have been right (give or take a bit), but the music has always been somehow lacking.

Part of the problem here, perhaps, is that I’ve learned Chinese really rather systematically, character-by-character, memorising tones, spending hours on end just doing the ground-work: and there’s a huge amount of work to be done, after all, before a page of Hanzi doesn’t fill you with a trembling anticipatory of terror. I’ve done OK in this respect; but there is something about learning in this way that has made my ex per i ence of the Chi nese lan guage some what dis join ted.

Thinking about all this, I remembered a wonderful book I read several years ago, by Timothy Rice, about Bulgarian Music called May It Fill Your Soul: Experiencing Bulgarian Music, in which he talks about the process of learning to play the gaida, the Bulgarian bagpipes. Now the thing about the gaida for a musicologist raised in the Western European tradition is that all those ornaments are really rather hard to notate on the stave. Rice notes that he began learning about Bulgarian music by ‘refining concepts from my training in Western music in order to explain what I heard and saw in Bulgarian music and dance’: but something essential about Bulgarian music remained out of reach (he refers to it as ‘le mystère des doigts bulgares‘), and he remained incapable of playing the typically burbling gaida ornamentation at the kind of speed that was required. How, he wondered, could anybody’s fingers work so fast?

The breakthrough came when he realised that his Western European concepts of ‘melody’ and ‘ornamentation’ (perhaps mirroring the old philosophical distinction between ‘substance’ and ‘accident’…? But that’s a discussion for another day!), that these analytical categories, would not cut it, when he started to just ‘play around’ physically with the instrument, copying the way that he saw Bulgarian musicians playing around, moving his fingers the way Bulgarian players did; and when he did, these concepts of ‘melody’ and ‘ornamentation’ fused into ‘a single concept expressed most vividly in the hands, not in musical notation.’

A concept expressed in the hands? What could this mean? Here Rice draws a connection with how children learn to play music in Bulgaria, which is largely by listening and by physical imitation. A concept expressed in the hands is a way of moving, a way of embodying music, born out of a close attention to what other, better players do. If you listen enough, watch closely enough, and move your fingers in imitation of what you see, then something happens. And this is what:

The effect of this conceptual shift from notated ideas to movement ideas astonished me. I went from tense, slow playing to relaxed, fast playing in the blink of a concept. Without further practice, I doubled my playing speed, relaxed my hands, and emitted more ornaments than ever before. Without had found the elusive ‘gaida player’s fingers’ and solved le mystère des doigts bulgares. (84)

What does all this have to do with Chinese? Well, remembering Rice’s account of his Bulgarian music experience, and thinking about the music of language, I’ve had a small insight into how to improve my Chinese. The other day I realised I realised that the concepts that I had been labouring under—the concepts of ‘initials’ and ‘finals’ and ‘tones’ and so forth, concepts of ‘characters’ and ‘words’, even—could be blended into something else: a physical, embodied concept that was, for want of a better way of putting it, the concept ‘speaking Chinese‘. And so I got up from my desk where I was studying, and started to declaim the dialogue I was working on, with gestures, watching the way my mouth moved in the mirror, turning myself bodily into a Chinese speaker. And, as with Rice’s experience, something changed. Within ‘the blink of a concept’, I was speaking with a kind of ease that I have hitherto never managed. Later on, when I met up with my Chinese friend, she was astonished. ‘Your Chinese sounds like Chinese, she said.’

Of course, there’s a long way to go, and I’m not expecting anything like fluency any time soon; but I feel that here I’ve turned at least one corner in this twisting path towards something like eventual competence in the damnably hard language that is Chinese. And this says something, I think, more generally about what it is to learn, about how learning is not just an acquisition of further bits of information, but is also a refashioning of the body and what we do with it. But that, too, is perhaps something for another day.

P.S. If you were disappointed that this post wasn’t about Louis MacNeice, then click here.

July 19, 2012

Snorghs, Sailors, Philosophy and Mood

Interdisciplinary Humanities: Children’s Media. Spring Issue 2012

Interdisciplinary Humanities: Children’s Media. Spring Issue 2012

With apologies for cross-posting from my personal website; but I’m very pleased to have received this morning two copies of the Spring Issue of Interdisciplinary Humanities journal, which includes my essay on “What the Snorgh Taught me about Emmanuel Levinas”. It’s a fairly personal essay/paper about the questions around children’s literature, creative writing, research and philosophy. The paper started out when I began to realise that the process of writing my children’s book, The Snorgh and the Sailor was (whatever Martin Amis might say about children’s literature) one that fed back into my philosophical writing, opening up new questions and lines of inquiry.

Here are some quotes, for the fun of it. Some of these ideas I might follow up in future posts here at The Myriad Things:

Far from being a way of passing the time for those suffering from various kinds of mental impairment [as Amis suggests], it seems increasingly apparent to me that the writing and reading of children’s literature can lead to precisely the opposite: to new kinds of freedom, to the development of new ideas…

…and…

“Philosophers are often more like Snorghs than they are like Sailors, which is to say that they generally prefer solitude, their own soup, routine, gloom and drizzle to high adventure, storytelling, good cheer, and companionship…”

…and, finally…

Philosophy, as all diligent readers of Heidegger will know, is fundamentally rooted in mood; and mood acts as a kind of framing of the possibilities of the philosophy that grows out of it. But part of the power of narrative and of story lies in the fact that stories work by means of the transformation of moods, from one state to another, opening up new possibilities of thought as they do so.

I’ll pick up on some of these things here as time goes on. Meanwhile, the paper should soon be available via EBSCO’s Academic Search Premier (if you don’t have access, get in touch and I might be able to root out a draft copy somewhere).

What the Snorgh Taught me about Emmanuel Levinas

Interdisciplinary Humanities: Children’s Media. Spring Issue 2012 I’m very pleased to have received this morning two copies of the Spring Issue of Interdisciplinary Humanities journal, which includes my essay on “What the Snorgh Taught me about Emmanuel Levinas”.

Interdisciplinary Humanities: Children’s Media. Spring Issue 2012 I’m very pleased to have received this morning two copies of the Spring Issue of Interdisciplinary Humanities journal, which includes my essay on “What the Snorgh Taught me about Emmanuel Levinas”.

“Philosophers are often more like Snorghs than they are like Sailors, which is to say that they generally prefer solitude, their own soup, routine, gloom and drizzle to high adventure, storytelling, good cheer, and companionship…”

The paper is available via EBSCO’s Academic Search Premier. If anybody who doesn’t have access to EBSCO wants a draft copy, get in touch and I’ll send one.

July 18, 2012

Weaving Words: 18 July 2012

Very much looking forward to doing an reading/event at Weaving Words writers group this evening. More about the writing group can be found here.

Will Buckingham's Blog

- Will Buckingham's profile

- 181 followers