Will Buckingham's Blog, page 33

June 20, 2012

Lightness, and Editing for Pleasure

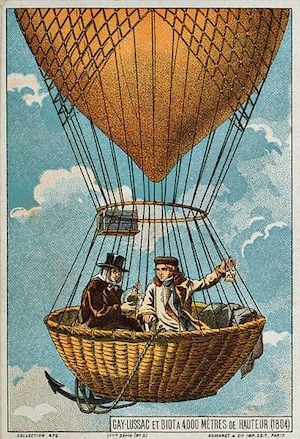

Gay-Lussac et Biot à 4,000 mètres de Hauteur (1804) — Source:Wikimedia Commons

Gay-Lussac et Biot à 4,000 mètres de Hauteur (1804) — Source:Wikimedia Commons

I probably shouldn’t be writing this, as I have a deadline on the philosophy book manuscript, which needs to be sent off by the end of the month; but there’s time for a quick post on the subject of writing and pleasure.

The philosophy book I’m working on has been through more drafts than I can possibly count; and it is good to see it close to completion. In terms of editing, I am now in the final edit, which I consider to be a kind of ‘editing for pleasure’. Editing, I think, is always a process of editing for something or other: editing for consistency, for factual accuracy, for coherence or argument, for sentence construction and so on. This is one reason that for me at least, things need multiple edits, because each time you are looking for something different.

So, in this final edit, I am editing for pleasure. That is not to say that I am editing because it is pleasurable—by this stage, I just want to get it done, and it would be more pleasurable to go and sit with a book in the park; but instead it is to say that I am editing to make sure that the text of the book itself is pleasurable. I see editing for pleasure as partly a matter of attention to the cadence and music of language, partly a matter of excising any lumpy and inelegant parts in the argument, and partly a matter of preserving that quality which Italo Calvino, in one of my favourite books, calls “lightness”.

Philosophy is a famously “heavy” subject. We talk about “weighty” tomes; we talk about “weighing” arguments, we talk about “gravity”. And particularly when it comes to the kind of continental tradition to which I am an heir, weight is often considered a virtue, and lightness associated with the flightly, the irresponsible, the hopelessly shallow. Philosophers are terrified of seeming “light”; and if they are interested in pleasure at all, as often as not it has to be a contorted kind of pleasure, a pleasure touched with darkness and with gloomy foreshadowings of death.

The kind of pleasure that I am talking about is a lighter, simpler (and less psychoanalytically tangled) thing than all this. It is about a delight in playing with patterns in language and in thought, it is about the excitement of finding new pathways, it is about the surprise of unexpected connections, and it is about the savouring of passing jokes. It is, I hope, a pleasure that has about it what Calvino calls the ‘lightness of thoughtfulness’, as opposed to the ‘lightness of frivolity’.

And this is not, I think, a matter of packaging, as if style and content could be separated entirely: it is also a matter of method. One of my contentions in the book is that there’s a commitment to the notion of existence as something inherently and fundamentally terrible that runs throughout Levinas’s work. It is a view that I do not share, and a view that I think is unhelpful. It seems to me that the notion of existence as terrible and weighty and dark and contorted may necessarily require a terrible, weighty, dark, contorted language; but, conversely, a lighter language may allow the breathing space for other possibilities, for other kinds of relationship with the world and with ourselves and with each other.

It seems to me that the prejudice that equates gloom with profundity runs deep, and not just in philosophy. So there will be those, no doubt, who find this lightness, these passing jokes, these strange conjunctions, this concern with the pleasure of the reader, frivolous. And these readers will no doubt be able to marshall weighty reasons why this is so. In response, I may—fearful of too much weight—pull out a few jokes, jokes that may serve to confirm their worst of their suspicions. And so it will go on. Nevertheless, I’m hoping that there will be some who manage to get hold of the book after it comes out in early 2013 (despite the regrettably weighty price-tag), and who might find in its pages a lightness and a pleasure that do not rule out thoughtfulness…

June 18, 2012

The Art Intervention Brigades

I’m just going to take time out from re-organising this website (and going through proofs of the novel, and pushing through the final edits of the philosophy book, and everything else that suddenly needs to be done by the end of June), to link to the wonderful Voyage à Nantes festival in France.

I was over in Nantes back in March, working with a fantastic group of students in the art-school, having fun with various creative-writing activities in French and in English. The idea was that the writing workshops, which lasted most of the week, would then be further developed by actor Will Courtais, and all this febrile creative energy would then eventually bear fruit in an event at the festival.

Well, all this has come to pass, in the form of the Brigades d’Intervention Plastiques (BIP – “The Art Intervention Brigades”), led by students, who are offering a fun and off-beat art tour of Nantes. The link is here.

Sadly, I’m not going to get out there to take part; but I’m delighted to see what has become of this project. Back in March when the people from the art school and I were interviewed about what our purposes were, and what our intended outcomes were, we confessed that we had no idea. We thought it might be fun. We hoped that what transpired, if anything at all, would be unexpected. And we acknowledged that it could all go very wrong indeed.

So it’s great to see that on this occasion, things did not go very wrong, and that those strange caffeine fuelled renga workshops (there’s a reason, I discovered, they use tea, and not espresso, for writing renga), walking/drawing/writing tours of Nantes, poems written in non-existent languages and the like have all paid off. All power to the Art Intervention Brigades, I say…

June 17, 2012

New website

Well, that wasn’t quite as painful as I thought it would be. Today I’ve refashioned WillBuckingham.com to use WordPress rather than textpattern. I thought that it would take all week, but I’ve got a skeleton site up and running in a couple of hours.

Things are not yet working as they should. I may well change the theme of the website, and there are some broken links. I also need to re-upload the various images. So my apologies for the glitchiness. But it does mean that, as time goes on, I can extend the website here in interesting ways, for example by adding more audio and such-like.

As I mentioned on my old site, I’m generally blogging over on The Myriad Things, rather than here, and I’ll keep this website for news updates about my various activities. I’ll post again when things have settled down; but for the time being, I need to get back to work with tweaking this site…

June 14, 2012

Cheese, Chinese and Chauvinism

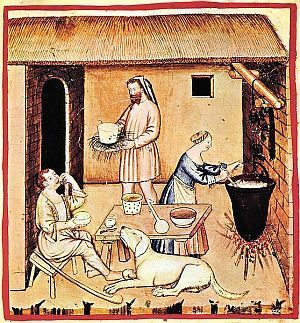

Cheese-Making in the 14th Century, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Cheese-Making in the 14th Century, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Recently I’ve been watching some philosophy programmes from Beijing Open University. It’s a slow process—transcribing as I go—but good as a way of practising my Chinese. I have realised that when it comes to language learning, you need to make use of materials that are themselves interesting. So when I bought Harry Potter (or Hali Bote 哈利波特) in Chinese because I thought it might be a good, easy read, I forgot that I’d never had the slightest desire to read more than three pages of the English version, so I really shouldn’t have been surprised when trying to read the book in Chinese did not improve the experience for me. You’d think that reading five pages of philosophy in Chinese would be more arduous than reading five pages of Harry Potter; but in Chinese, as in English, I find that the reverse is true.

Anyway, in the search for more interesting ways to improve my Chinese, I’ve been watching and transcribing these Beijing Open University programmes about philosophy, and they’ve been pretty entertaining and—occasionally—informative. And one thing that has struck me repeatedly in watching these shows is how the various scholars and talking heads are hung up on an idea of Chinese philosophy as something special. Not just something special as in something that has its own shape, form and history (everything is special in this sense), but something that is especially special: something that goes further, higher or deeper than any other philosophical tradition; something, very often, that non-Chinese philosophers are said to be unable to understand because, well, they are not Chinese; and something that has given Chinese philosophy a kind of higher historical destiny, almost a mystical function in the history of the world.

I am fascinated and intrigued by Chinese thought; but at the same time I am highly suspicious of these kinds of notions. They have the air of chauvinism. And I find the mysticism of these kinds of claims worrying, in part because if something is mystical, then you don’t need to think terribly hard about it—and this doesn’t seem much like philosophy at all.

Philosopher A: “How does this thing relate to that thing?”

Philosopher B: “Oh, it’s mystical, don’t you know?”

Philosopher A: “Yes, but how? By what mechanism?”

Philosopher B: “Mechanism? What kind of profane language is this? That which is mystical transcends all mechanisms…”

You get the idea. It’s seems to me that the assertion of the inherent rightness of any particular system of thought, and the notion that any one philosophical tradition might have some kind of mystically assured historical destiny, are both forms of cultural chauvinism that we might be better off without.

Nevertheless, this is a kind of chauvinism to which philosophers are often decidedly prone. And it is certainly not found only amongst commentators on Chinese philosophy. It also exists in European traditions. And it exists in the American traditions too, but I’ll stick to Europe for the purposes of this blog. Think of Emmanuel Levinas, who claims that philosophy is “the Bible and the Greeks” (no sign of Confucius or of Nāgārjuna, for example); or take the following passage from Husserl’s The Crisis of the European Sciences, written in the 1930s:

Europe’s greatest danger is weariness. If we struggle against this greatest of all dangers as “good Europeans” with the sort of courage that does not fear even an infinite struggle, then out of the destructive blaze of lack of faith, the smouldering fire of despair over the West’s mission for humanity, the ashes of great weariness, will rise up the phoenix of a new life-inwardness and spiritualization as the pledge of a great and distant future for man: for the spirit alone is immortal.

Now, there are many things to admire about Europe. We do cheese, for example, better than anywhere else on earth. We Europeans (yes, island-dwelling British readers, I am including you in this category) are masterful in our making of cheese. But when Husserl is talking about the historical destiny of Europe, he is—I think that it is safe to assume—not talking about cheese. And I think that the very idea that any one system of thought might bear with it a “mission for humanity” is, at best, overweening hubris, and at worst a dangerous delusion. These kinds of ideas do nobody any favours. They entrench ignorance by killing off curiosity, and this chauvinism and belligerence can often be used to shore-up broader forms of political chauvinism and belligerence. And this is a very bad thing indeed.

As Jay Garfield writes in his book Empty Words: Buddhist Philosophy and Cross-Cultural Interpretation (2002),

to treat philosophy as denoting something the Greeks and their German descendants did, and therefore as comprising nothing Asian, commits one to two grave errors: either one presumes falsely that no Asian ever did what the Greeks and Germans did (think reflectively about the nature of things) or one presumes that there is something terribly special about such reflection when done in Athens or Freiburg.

The same goes, of course, for Beijing or Shanghai. So it seems to me that philosophers, in general—wherever they come from—might do well to begin from a more modest starting-point when they think about what philosophy is and what philosophy can do. A sensible base-line seems to be this: to assume that philosophy is a matter, as Garfield says, of reflecting about the nature of things; to recognise that this is a human activity, that it’s one of the things that we do; and to see that our thinking about things is always necessarily within various kinds of traditions, conditions and contexts. In this light, perhaps also we need a sense that thinking is a kind of discovery, whether in relation to traditions we recognise as ‘our own’, or else in relation to other traditions, so that we can both be open to entertaining thoughts and possibilities from elsewhere, and also begin to rethink ideas from closer to home. And finally, we need to simply be on guard against the ideological assertion that this or that system of thought is somehow inherently and mystically supreme.

It is this openness to new possibilities (without taking leave of our critical faculties), and this willingness to rethink, that can best guard against this kind of philosophical chauvinism. Otherwise it seems to me that what passes for philosophy ends up with the kind of determined ignorance that is perfectly exemplified by this short fragment of dialogue from the film, My Big Fat Greek Wedding:

Gus: Now, gimme a word, any word, and I’ll show you how the root of that word is Greek. Okay? How about arachnophobia? Arachna, that comes from the Greek word for spider, and phobia is a phobia, is mean fear. So, fear of spider, there you go.

Schoolgirl: Okay, Mr. Portokalos. How about the word kimono?

Young Athena: [whispers] Good one.

Gus: [Pause] Kimono, kimono, kimono. Ha! Of course! Kimono is come from the Greek word himona, is mean winter. So, what do you wear in the wintertime to stay warm? A robe. You see: robe, kimono. There you go!

June 10, 2012

Philosophy, children’s literature and the question of branding

A couple of months ago, my children’s book, The Snorgh and the Sailor, was published. It has been one of the most demanding and delightful projects I’ve ever been involved in. Who would have thought that eight hundred words would require quite so much redrafting?

I fell into children’s literature somewhat by mistake, after becoming friends with the illustrator Thomas Docherty. Tom is a wonderful artist, and a lovely man; but when we decided to have a go at working together, I can remember feeling a little apprehensive. Part of the reason was that I was not sure I could write for this age group. Another part of the reason was that I was a writer who spent his time working on philosophy and novels for adults, and I couldn’t really see how writing children’s books fitted in. I worried about how my work as a whole would hang together. Wouldn’t it look, well, a little odd? Writers in the twenty-first century, I have been told more than once, don’t need to just be writers: they also need to be brands. If so, then what kind of a brand was I? My output as a writer is a curious mix—novels, children’s literature, pop philosophy, academic philosophy, Buddhist stuff, Chinese-related stuff, blogs. What, I have sometimes wondered, does it all add up to?

I put the question to one side—although it has popped up several times since—and got on with my various projects. And as the Snorgh took shape, I came to appreciate the particular delights of working in children’s literature. There really is something unutterably wonderful about seeing your words turned into images such as these (you can see more of Tom Docherty’s work at Snorgh.org or at thomasdocherty.co.uk).

The Snorgh Dreams Unsnorghish Dreams—Copyright Thomas Docherty

The Snorgh Dreams Unsnorghish Dreams—Copyright Thomas Docherty

Now that the book is published, I’ve recently discovered something else: that when you write a children’s book, you get letters—enthusiastic, creative letters—from schoolkids who have read the book, made their own books about it, written their own stories about your characters… And all of this is gratifying in a way writing philosophy books, novels and academic philosophy articles isn’t. Of course there are pleasures involved with these things also, but they are different pleasures (any academics reading this—when is the last time you so enjoyed an article that you decided to send a drawing to the author?).

Now that Snorgh is making his way in the world, and in good hands, I’m back to the philosophy, working on a relatively substantial monograph on Levinas and storytelling, due to be published in 2013. It is about as different from the children’s book as it is possible for a book to be. In terms of author branding, this is a disaster. Nobody is ever going to write on the back cover of the Levinas book, “If you liked The Snorgh and the Sailor, then you’ll love this!!” So, what does this add up to in terms of a whole? What is my ‘brand’, my ‘unique selling point’, my ‘thing’?

The moment I write these questions down, I realise that they go against almost every single reason that I write. I write because I want the freedom to explore stuff, because I want to move from one thing to another, because I’m interested in too many things not to write. And, of course, I write because I want people to read what I write. But that doesn’t mean that I need everybody to do so. I never, ever want to see a train full of people all reading identical copies of one of my books. I never, ever, want to see a train full of people all reading the same thing, whatever the book. So: different books, different audiences. It seems that already several thousand people have read the Snorgh—the first print-run sold out in a few weeks, and it doesn’t take an age to read, so they must have done. Conversely, I suspect that only a handful of people will ever read the Levinas book cover-to-cover (although others may pull it off the library shelf from time to time). When it comes to the Levinas, I wouldn’t inflict it on most of my best friends. As poet Erin Mouré said at a talk I went to a few weeks back, “Books are emigrants, they belong in the places where they arrive”; and I’d very much like each thing I work on to set out, suitcase in hand, and find its way to a different destination.

This is not to say that these different projects are not linked. Often they are, even if not obviously so. Going back to the philosophy book after the children’s book, I can see that—perhaps surprisingly—writing about Snorghs is helping me write about Levinas. It is helping in terms of style: I’m thinking about those things that matter in children’s literature—concision, clarity, humour—and that should but often don’t matter in philosophy. It’s helping in terms of method: I’m reworking some of the more lumpen philosophy by means of telling stories. And it is helping in terms of thinking: writing the Snorgh (which itself owes something to Levinas) has allowed me to ask questions that I hadn’t asked before. Questions such as, ‘What happens to Levinas’s thinking when the stranger becomes a friend?’

And then, this summer, I’m planning to start working on a few book-length projects now that have little to do with Snorghs or Levinas. None of this will do anything for my ‘author brand’. But who cares? As I see it, branding is what farmers do to cattle, so that should they stray out of their enclosures, they can be dragged back, bellowing and hollering. Better to be something small and unobtrusive—a stoat perhaps—something nimble enough to slip between the fence-posts, to go from one field to another, following its nose and its own purposes…

June 8, 2012

Nocturnal Philosophising

Well, I survived the My Night With Philosophers event at the Institut français, and so I’m now heading home after a long night of heady philosophy for some serious sleeping. It was an excellent and astonishingly well-attended event. I suspect that the organisers were surprised by the turn-out: you could see the light of panic in their eyes as the foyer filled up with more and more people, as the photocopier began to malfunction, as the coffee supply failed to keep pace with the incessant demand, and as the queues for the sessions grew longer and longer…

But, for all that, it was a wonderful, graciously organised, friendly and stimulating night. The people at the Institut did a remarkable job at programming and organising the event, and the volunteers did a good job at staying sane and cheerful throughout what must have been an exceedingly busy and very, very long night for them all. There was some thinning out of the crowds from two o’clock onwards, but at four o’clock in the morning the main lecture theatre was still densely populated, and most of us were still awake and alert, coffee or no coffee.

You can fit a lot into twelve hours, although inevitably I missed some of the things I would have liked to have attended as there was simply too much to do. By five, more or less sated when it came to philosophy, I managed to get into the café for a proper coffee, the queue having at last died down. I ordered a cappuccino. A woman from the BBC who was standing next to me at the bar stammered something like, “It’s five AM, they’re playing Celine Dion, there are philosophers dancing: that’s how a night should end…”, then she headed off through the crowd with two large gin and tonics. I found myself a corner and wrote up some scribbled notes in my notebook. All around me people chatted about Derrida, about politics, about Quine, about how speaker x was pretty darned hot, about how one might best go about plotting a revolution, about how next time they’d bring a thermos flask, and about how they really hoped there would be a next time.

There is a perception—a misperception, I think—that in Britain we don’t really “do” philosophy (whilst in France, presumably, it’s all they do. Oh, and go on strike, of course). But the fact that an event like this can draw in such massive crowds suggests that there’s a real appetite for this stuff. Even some philosophy sceptics I talked to last night seemed excited to be there, and were willing to acknowledge that there are worse things to do with your time than spend the night with a philosopher. Or, in fact, with a whole crowd of them…

Snorghs, philosophers and insomnia

A very quick post this, written in a coffee shop at St. Pancras, where I’m waiting to head down to the Institut français, for their My Night With Philosophers event, a twelve hour all-night extravaganza of philosophical joy. I’ve written about the event, and about the connection between philosophy and insomnia, on my new blog The Myriad Things. In general, in future I’m going to keep blog posts here on WillBuckingham.com relatively brief, for announcements and things, and keep longer pieces over on The Myriad Things. So do go and visit the blog and bookmark it. If you look in the sidebar of this blog, you should see that I’m now syndicating stories from the other blog here.

In terms of announcements, I’ve just got a short one. I’m delighted to say that my stoical little Snorgh has been recommended by Julia Donaldson in her list of six picture books to share, along with classics like Dogger, and quirky little masterpieces like Dogs Don’t Do Ballet. You can find out more by going here.

June 7, 2012

“One must not sleep…”

In his book, Discovering Existence with Husserl, Emmanuel Levinas writes “one must not sleep, one must philosophise.” I’ve long been a little sceptical of this. Many times I have thought, whilst being held hostage by some philosopher or other until late in the night, that quite the reverse is true: in other words, at times one must not philosophise, but instead one must sleep.

Nevertheless, I’m heading down to London tomorrow for an insomniac night of philosophy called My Night with Philosophers, at the Institut français in South Kensington. The event is free, plenty of coffee is promised, and there are some truly excellent speakers laid on. But because I’m not quite as hard-core as Levinas, and I think that on balance both philosophy and sleep are good things, I’ve bought an open ticket home, just in case I flag and want to hop on the last train. However, from where I am sitting just at the moment, it all looks so damnably interesting that I’m tempted to stay the whole course.

The Levinas quote, incidentally, comes in the middle of a discussion of the questionableness of self-evidence in philosophy, and how—in his view at least—phenomenology is a matter of revealing not certainty (as Husserl once thought, at least earlier on in his philosophical career), but instead a kind of quivery equivocation in thinking. I’m busy writing about all this stuff at the moment, for a book deadline that is about to fall at the end of the month (about more anon.); and until I heard about the event at the Institut français, I was going to spend the weekend editing. But looking at the programme, I simply can’t resist taking a short break, and making the trip to London.

All of which gives me a chance to post a small extract from the aforementioned forthcoming book, where I deal with such important matters as philosophy, insomnia, the tragedy of being and coffee:

If you find yourself waking at three o’clock in the morning, assailed by the horror of existence, insomnious and unsettled, you might indeed begin to suspect that there is a deep-rooted tragedy at the heart of being; but with the return of the bon sens that Nietzsche associates with breakfast, you might recognise that the insomnia of the night before was due to a combination of too much time in the melancholy company of philosophers, and far too many cups of coffee. The problem is not in being itself, in other words, but merely in associating with the wrong kinds of being at the wrong kinds of time.

Hopefully—if I hold out that long—by breakfast time on Saturday I will have managed to have kept hold of a degree of bon sens; and if so, I’ll post an update some time over the weekend about how the event went. If you are in London, it’s well worth coming along too. Look out for me. I’ll be somewhere in the corner, red-eyed, clasping a mug of coffee, wearing an Epicurean “Moderation is Fun” T-shirt, and muttering incomprehensibly about phenomenology and insomnia…

Image: My Night With Philosophers Website

June 2, 2012

Propaganda, Home and Away

This weekend is the Diamond Jubilee weekend here in the UK. What this means is that our head of state, Queen Elizabeth II, has now sat on her throne (we still have thrones in this quaint little nation of ours) for sixty years. And so extra holidays have been proclaimed, people are hanging out flags, and the Queen herself is planning to begin her celebrations of this extended weekend by going to the Epsom Derby—one presumes to take a flutter on the horses.

This weekend is the Diamond Jubilee weekend here in the UK. What this means is that our head of state, Queen Elizabeth II, has now sat on her throne (we still have thrones in this quaint little nation of ours) for sixty years. And so extra holidays have been proclaimed, people are hanging out flags, and the Queen herself is planning to begin her celebrations of this extended weekend by going to the Epsom Derby—one presumes to take a flutter on the horses.

There are various other kinds of celebrations extending all the way to Tuesday: street parties, beacons being lit across the country, flotillas, concerts… And there is no denying that many people seem very, very happy about the whole affair. Just down the road from us, somebody has gone to the trouble of painting a union jack to cover the entirety of the wall in front of their house. That’s how happy some people are.

The media, too, are in something approaching ecstasy, the kind of ecstasy that immediately dissolves the critical faculties. Nicholas Witchell, the BBC’s royal correspondent, is singing the praises of the Queen, and how she is a “focus of unity within the country’s increasingly diverse communities”, and how the crowds attending the Jubilee tour so far have “proved the doubters wrong.”

I confess that I am a doubter. I’ve been wondering a fair amount about this whole Jubilee business. I’ve been wondering at the strange absence of critical thought on the part of the media. I’ve been wondering about the messages that we are being given. I’ve been wondering precisely what it is about the fact that crowds turn out to see the Queen that proves me, a doubter, wrong. Are there not legitimate doubts about the monarchy (doubts that are in no way “disproved” by crowds)? Surely no political system should be seen as being inherently beyond doubt.

I don’t want to rake over all these doubts about the Monarchy and about republicanism (because whilst broadly republican, I recognise that there are also legitimate doubts about this) here. What I do want to do, however, is to point out how very, very odd this whole media circus, this astonishingly uncritical and one-sided reporting, actually is.

Recently, I was listening to a BBC news report about the 90th anniversary of the Communist Party in China, broadcast back in 2011. The voiceover went like this. “This is a partial version of history with a clear message: Mao Zedong’s communist party saved China. This propaganda is fed to children too. These children love the party, even before they are old enough to understand why. ‘We’re here to remember the party’s great achievements’ says this girl.”

But then I turn to watch news reports of schools that have gone “Jubilee crazy”, so that they do “Jubilee geography” and “Jubilee science”, and they make bunting and they all cheer when the reporter says that they are the most patriotic school in the country. Or I see another school designing (somewhat oddly) paper knickers for Queen, on the occasion of the Jubilee. And I wonder about the partial version of history that we are promoting here. Of course, we might feel intensely that this is very different. We have celebrations and popular feeling; they have orchestrated political pageants, and manipulation by means of propaganda. That is how the story goes. But there is no reasonable way to sustain this view. The intensity of our feeling is perhaps precisely because we have a prior commitment to seeing the system under which we live as somehow inherently good. And where, one might ask, does this commitment come from…?

Of course, one cannot but give a partial version of history: there is no complete version, other than history itself. And yet there is, in all of this media hoopla, almost no note of uncertainty, certainly no mention of the word “propaganda”—a word that we use so freely and with abandon when talking in news reports about other nations, but that we never mention in relation to our own—no room here for doubt.

When our critical faculties are side-lined, and when critical voices are ignored, suppressed or drowned out, when large-scale political theatre is being mounted (and I am not entirely averse to large-scale political theatre), it is worth asking about the partial version of history and of society that is being promoted. It is worth asking about viable alternatives. It is worth asking some of the more difficult questions that we are being discouraged from asking.

May 31, 2012

Divination and Doubt

Emperor Shun Performs a Divination - Wikimedia Commons

Emperor Shun Performs a Divination - Wikimedia Commons

For the last seven years or so, I have been up to my ears in one of the strangest books in the world, the Yijing 易經, or Book of Changes. The Yijing (or, as it is often more popularly known, the I Ching) is, by any measure, one of the oddest books in existence: a bronze-age manual for governing, a divinatory text, one of the foundations of Chinese culture, a book that made Leibniz’s pulse race, and one of the texts most beloved of flaky New-Agers in the West. And because, perhaps, I like to think of myself as more or less sane, I have tended to be a little shy of talking about the Yijing. It is, after all, a book that attracts all kinds of quixotic crackpots and loons, a motley and curious company to find oneself amongst.

My own interest in the book is that I’ve been putting together a ‘novel of sorts’ that is based on the sixty-four hexagrams of the Yijing, a novel that mixes short stories, travel writing and wayward philosophical speculation. Perhaps one of my inspirations has been Calvino’s curious little book, The Castle of Crossed Destinies, where grids of Tarot cards are used as a kind of story-engine to generate interlocking tales. This ‘novel of sorts’ is probably a fairly quixotic project in its own right, but it’s been a fascinating business. And over the years, my sense of what the Yijing is, and what it can do, has changed.

Seven years ago, when I first started looking seriously at the Yijing, I had no time for divinatory practices, which seemed like so much superstition. And I still think now that using the Yijing as a way of foretelling the future is, well, just a little bit nuts. But I’m increasingly interested in how one might use divinatory tools as tools for thinking. There’s a great quote from Yang Wanli 楊萬里, which I found in Ming Dong Gu’s excellent book on Chinese Theories of Reading and Writing, where the poet and philosopher says that, “The profound implications of the Book of Changes plunge people of the world into doubts and make them think.”

It is this connection between divination and doubt that, I think, makes divination potentially a useful tool for thinking. Divination is popularly seen as a tool for generating certainty. You don’t know who to marry for certain? Hey, why not check your horoscopes and then you’ll really know. You can’t decide whether to take that job or not? Well, my pretty one, gaze into my crystal ball and we’ll see what we can see…

This, I think, is probably not a sensible way to lead one’s life. I can see no reasonable mechanism by means of which these kinds of divinatory tools can move us from uncertainty to uncertainty: they don’t give us any new data about the world, they don’t tell us about anything. If you are manipulating a bunch of yarrow stalks, for example, those stalks are even more ignorant than you are about the question of whom you should marry. They know nothing, and there is nothing about your manipulation of this particular bits of the world that can magic knowledge into the stalks, however much incense you burn. But that is not to say that they are useless tools if used in the right way.

What divination can do, I think, is introduce novelties and uncertainties into a system that has become too rigid. Let me give an example. Let us say that I indeed find it very hard to decide whether to marry or not. On the plus side, the object of my affections is intelligent, kind, well-read, and has fantastic dimples when she smiles. I know for a fact that I will never encounter dimples like that again. On the minus side, she slurps when she eats soup. And I love soup. So I have something of a dilemma on my hands; and as a result I find myself going back and forth between these two poles, at one moment browsing the internet for wedding rings, at the next thinking about my exit strategy.

What is striking about these kinds of situations, these kinds of dilemmas, is that they are often very thin, or at least they become so very quickly. My entire existence becomes focussed on this one, bald question, to the exclusion of all else. The world empties out of richness and complexity. Do I? Don’t I? Do I? Don’t I? I go round and round, and don’t get anywhere.

So I cast the Yijing. And, for the sake of argument, I obtain hexagram fifty-six, which is lü 旅, ‘The Wanderer’ with a changing line at the top (for the next bit in my argument you don’t need to know anything about the Yijing, incidentally, so I’ll gloss over details). I look this up in my big, impressive book and I read passages such as, “The wanderer is such that prevalence might be had on a small scale”, and “The bird gets his nest burnt. The Wanderer first laughs and then later howls and wails.” Hmmm, I say to myself. What could it mean? Then I note that when the top line of the hexagram changes, I end up with hexagram sixty-two, called “minor superiority” (“the flying bird is losing its voice, for it should not go up but should go down…”)

Now what happens? If all goes to plan, this: my mind—which has been happily flip-flopping between only two possible futures for far too long—now starts playing, of its own accord, with other images: birds and wanderers and nests. And what was a binary decision now becomes a far richer field of symbols and images and ideas that spreads out around me and that loosens me up. New questions occur to me. What does it mean to burn one’s nest? Is it a good or a bad thing? Who is the bird? Who is the wanderer? And are these even the right questions? And then, because I need to get out, I go for a walk, and let the images settle, and I watch the birds going up and going down, and…

…well, after that, who knows? But perhaps something happens that would not have happened, or not in the same way, without this intervention. In other words, one of the big problems with decision-making is that we become fixated on dilemmas, and thus we lose our suppleness and attentiveness. The introduction of chance elements, this multiplication of doubt, makes us lighter on our feet, it frees us from this fixation on either/or, it opens up new creative possibilities. As one of my favourite books of the moment, the sixth-century Wenxin diaolong (“Carving of Dragons and the Literary Mind”) puts it, creativity arises when one seizes the chance event at just the right moment. What if divinatory tools worked precisely as ways of sowing a little disorder, and cultivating this quicksilver attentiveness to what transpires from this disordering of our too-narrow schemes?

And so, if we care about making decisions that are less constrained, more open to possibility, then it seems to me that divinatory tools can be extremely helpful in unseating our habitual trains of thought, and sending us skittering in new directions, towards new possibilities. However, to see divinatory texts as books that can tell us what to do, as texts that deliver us over to certainty, rather than to further questioning and exploration, is, I think, dangerous. It assumes that the texts hold some deeper wisdom than that which we ourselves can muster, and therefore it risks looking like a disavowal of our responsibility for our own actions.

Anyway, having said all this, I’m going to finish writing this blog post, and to contact the authorities at the university where I work, to offer them my services as diviner-in-chief. I think that a modern, forward-thinking institution deserves no less. And I bet they’d give me a very smart ceremonial hat.

Quotes from the Yijing come from Richard John Lynn’s translation, The Classic of Changes.

Will Buckingham's Blog

- Will Buckingham's profile

- 181 followers