Will Buckingham's Blog, page 32

July 18, 2012

Philosophy at a Gallop

Napoleon’s attempts an assault on Kant’s “Critique of Pure Reason”. Jacques-Louis David, 1800.

Napoleon’s attempts an assault on Kant’s “Critique of Pure Reason”. Jacques-Louis David, 1800.

Every summer I try and make a point of launching into a Big Fat Philosophy Book that I have, for some reason or another, not got round to reading before. My ideal holiday reading, in other words, is not a thriller or an airport blockbuster, but instead is something appetisingly dense like Merleau-Ponty’s The Phenomenology of Perception. Merleau-Ponty is my choice for this summer, because this is a book that I have made use of, talked about and skirted round for years, but one that I have not actually ever read from beginning to end.

Big Fat Philosophy Books are always rather daunting things. One of the reasons I like reading philosophy is not that I turn page after page thinking, “Hmmm… that makes sense,” but instead that I turn the pages thinking, “What the hell’s going on?”, whilst being aware — somewhere just on the threshold of perception — that my insides are being subtly realigned. And one of the things I have come to appreciate is that reading philosophy is, in part, a way of making friends with bafflement, non-comprehension and bewilderment; it is a way of seeing that these things, too, are a part of what it means to think.

Every time I launch into a Big Fat Philosophy Book, I am reminded of the sage advice of the philosopher Franz Rosenzweig, who has a lot of interesting things to say on reading and on thinking. Rosenzweig claims, in his essay The New Thinking, that when we read philosophy, we often make the mistake of thinking that what we are reading is “especially logical”, that ideas follow each other in neat chains of reasoning, and that each sentence leads on to the next. But then he says, “Nowhere is this less the case than in philosophical books.” Often, in fact, the sentences that follow make sense of the sentences that have come before. Or when you close the book, suddenly you get a sense of what was going on at the opening. Philosophy books, in other words, are often complex systems of thought that do not unfold proposition by proposition, but that require instead a kind of wholehearted engagement, a passage through them, before they begin to make sense.

How, then, to read philosophy? Rosenzweig’s answer is clear: Napoleonically. You launch in, at at gallop, “in a bold attack on the enemy’s central force”, in the hope that the smaller fortresses will fall once the decisive battle has been won. Of course, you don’t know at what point this battle will take place: and, Rosenzweig notes, it will surely not be in the same place for two different readers. But the important thing is this: “Above all: rush! Do not stop!” The worst that can happen is that you end out galloping out the other side, none the wiser; but usually, by the end, something has happened.

So this is how I will be reading Merleau-Ponty this summer. I’ll be putting on my Napoleonic bicorne hat of firm resolve, saddling up the horses of philosophical hunger, and launching an offensive on the citadels of Merleau-Ponty. I’d say “Wish me luck!”; but I won’t, because I bet Napoleon never said “Wish me luck!” before he galloped off on his latest campaign. He probably just said, “Adieu,” set his jaw nobly towards the horizon, and galloped off…

July 14, 2012

Philosophers, Cleverness and Storytelling

Philosopher: Engraving by Marco Carloni: Wikimedia Commons

Philosopher: Engraving by Marco Carloni: Wikimedia Commons

I’m very happy to have just signed a contract with Bloomsbury for a book about Levinas and storytelling called Levinas, Storytelling and Anti-Storytelling. The book comes out some time early next year, all being well, and it’s been a long time in the making. It aims to read Emmanuel Levinas, the French-Lithuanian philosopher of ethics, both as a storyteller of ethics, and as somebody who calls storytelling to ethical account. There is an intriguing tension here. On the one hand Levinas talks about ethics (almost despite himself) by recourse to the telling of stories; but on the other hand he raises all kinds of interesting questions about the ethical dangers of certain kinds of storytelling.

As a writer of stories myself, it seems that I cannot prevent myself from reading philosophers as storytellers of sorts. Of course, telling stories is not the only thing that philosophers do; but the boundary between storytelling and philosophy is always a blurred one. And the thing about stories is that when you are caught up in them, they can seem so terribly, terribly compelling, not to say self-justifying; but when you step outside of them and ask, ‘why this story and not another?’, then the answer is not always clear.

This is a problem that I often have with philosophy. To take an example, let us imagine that Philosopher A, who is probably more clever than I am or ever will be, says x. I read about x and it all sounds pretty persuasive. Not only is this really rather convincing, but x is (Philosopher A claims) a vital key to the puzzle of existence, without which we will all be the poorer.

I’m just about to sign on the dotted line when Philosopher B—who is at least as clever as Philosopher A—comes along and says that Philosopher A is completely wrong. ‘It is clear,’ (Philosopher B claims), ‘that we cannot sustain the position x; therefore I propose that Philosopher A is a buffoon and that y is the case.’ Following Philosopher B’s argument, again I am a convert. ‘Of course,’ I mutter, ‘how could I have not seen it.’

At that moment, Philosopher A gets wind of this scandalous attack, then stands up, red-faced—nobody likes to be called a buffoon—and cries out, ‘Philosopher B has clearly misunderstood!’, and sits again down to write a further refutation. So it goes on. And looking on, for those of us who are clearly not nearly as clever as Philosopher A or Philosopher B, it becomes harder and harder to know how we might decide between one or the other.

And it is true, of course, that forming arguments and the practice of reasoned debate are a part of philosophy; but what I very much suspect is that these things are not as large a part of philosophy as many people—and many philosophers—think. If they were, you would find philosophers changing their mind much more frequently than they do. You would find Philosopher A and Philosopher B coming to an agreement, and then going out together for a candlelit dinner, to talk about their new-found mutual understanding over a bottle of wine. You would find that the rallying cry of philosophers was not, ‘Bumkum!’ (or whatever those old Oxford philosopher-dons of legend used to exclaim) but instead, ‘oh, yes, you’ve got a good point there!’ As it is, this is not something you hear philosophers saying very often.

Often it seems to me that the role reason plays in philosophy is that which was summed up by Saint Anselm when he said ‘Credo ut intelligam’: ‘I believe that I may understand’, rather than ‘I understand that I may believe.’ Anselm’s astute point is that arguments about the existence of God do not convert people; but they do demonstrate that, if one is signed up to this particular story, this story can be made consonant with the demands of reason. And this is often what many arguments in philosophy are about, even if this is not acknowledged: the attempt to bring pre-philosophical commitments in line with reason.

This is why stepping back from the heat of some of the often fearsomely technical arguments of the philosophers to ask ‘what kind of story is being told here?’ can be salutary. It allows us to see that even the most meticulously reasoned argument is often a move in a game of rhetoric, and that what is being presented is instead a complex story—shot through with reason and argument, but a story nonetheless—about how the world hangs together, about what we ought to do with ourselves, about how we ought to think, and about what ultimately, if anything, matters. It is not that reasons are not important. They are. But they often take their force from the part they play within a particular story or set of stories; and sometimes the way to make progress, to be capable of thinking differently, is not to tackle these reasons from within the story being told, but by spinning new tales, and from these new vantage points, seeking new reasons and new justifications…

July 9, 2012

My Secret Life as a Writer of Romance

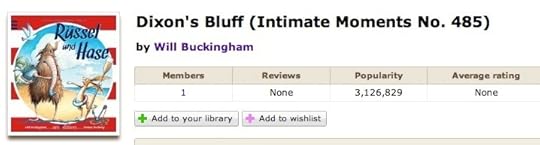

Well, it looks like I’ve been found out and my cover as a writer of romance novels has at last been blown. This morning I headed over to LibraryThing.com, where I saw the following:

Dixon’s Bluff, 1993 Sally Tyler Haynes

Dixon’s Bluff, 1993 Sally Tyler Haynes

Now, my German is far from excellent, but if I were to translate Rüssel und Hase, the title on the cover in the picture, I would probably not translate it as “Dixon’s Bluff”. Instead, I would translate it as “Trunky and the Hare”; or, taking artistic license, I might decide that it should be translated as “The Snorgh and the Sailor.” I can’t help fearing that those hoping for intimate moments will find themselves disappointed by the tale of the seafaring Snorgh, in German.

Given that I was supposed to have written the book, however, I thought I would look up Dixon’s Bluff (which sounded to me from the name alone like a kind of low-budget remake of Dawson’s Creek) online. The book turns out to be a romance published back in 1993 (“Dixon MacCauley was a desperate man, playing a dangerous and deadly game, and suddenly, into the middle of it came a nanny named Liza Snow and an innocent little girl named Jill…”), written by Sally Tyler Hayes. As the cover of the original is so very fine, I thought it worth sharing here.

This is the second time in as many months that I have been given credit for books that I haven’t written. The last one was when there was a little accident in the children’s department of Waterstones’ that led to being credited, again in error, as the author of Princess Polly and Pirate Pete’s Potty Training Book.

As I wrote in a previous post, it is true that the things I write cover a fairly broad range—from children’s books to philosophy to literary fiction—but potty training and romance are domains into which I would not presume to move, areas of expertise which I am content to leave to others.

July 4, 2012

Research, or something like it (Part I)

llustration from Jules Verne’s “Around the Moon” by Bayard and de Neuville. Wikimedia Commons

llustration from Jules Verne’s “Around the Moon” by Bayard and de Neuville. Wikimedia Commons

Every few years, here in UK academic circles, there is a curious circus known as the REF, the “Research Excellence Framework”, a bizarrely arcane ritual of humiliation where academics struggle to demonstrate that their research is not merely good (one might have thought that being “good” was a sufficiently high demand, although apparently this is not so) but is instead excellent. And because this is a rigorous exercise, scholars are asked to prove their excellence in research by submitting to learned boards of their peers a range of “outputs” that are scrutinised using the best scientific and divinatory methods, so that these works may be awarded stars. Not real stars, of course; not even the kinds of stars that are handed out to primary school children, shiny sticker-stars, but just notional stars, the Platonic forms of stars that are more true and real than any actual star or representation of a star could ever be.

The next round of the REF is in 2014; and so, ever the faithful employee, I have over the past year been compiling and recompiling lists of things that I have written (“outputs”, I must remember to call them) and submitting them to various committees, so that I can find out how many hypothetical stars they might get were they to be submitted to the REF itself. Many colleagues and friends have been doing the same. And this is instructive, in a gloomy, gallows-humour kind of way. I submitted my children’s book, because it’s sold more copies than all my other books put together, and been translated, and has nice pictures in it, and features a very impressive whale. However, I was sad to discover that this book is (hypothetically) worth no stars at all, on the grounds that there was “no research content”. “But it’s got a whale!” I wanted to protest; but in the end, I restrained myself, knowing it was hopeless. I also submitted an obscure article that I wrote for a journal few people will ever read, one of those academic journals run by huge corporations that charge exorbitant fees, to virtually ensure the journal goes more-or-less unread, whilst along the way stripping authors of their copyright into the bargain: no readers, no rights—the kind of deal that no writer should agree to, in other words. This article—which was not at all bad, but which will probably languish in obscurity forever—was deemed worthy of a hypothetical three or four stars, despite being entirely free of cetaceans. And it’s not just me who has problems: as I write this, all across the country, people are anguishing over those hypothetical stars, as they dream of excellence.

So, anyway, what I want to write about is not the REF itself, a weirdly skewed process that will eventually, one hopes, be swept away by the tides of history, but instead the question of research. In the academy, at least, creative writing is seen somewhat unhelpfully as a kind of subset of English literature. You would have thought that the study of literature was a subset of the broader field of creative writing—on the grounds that some people write creatively, and that this being the case, some people decide to study what other people write creatively—and that the study of English literature was a subset of the broader study of literature, in other words, a subset of a subset of creative writing; but that is not, alas, how things are seen.

This is a problem. The thing is this: writers who write novels and stories and poems are doing a rather different kind of thing from those people who spend their life writing learned papers on Emily Dickinson, or Beowulf, or anything like that. That’s not to say that it is a better or worse kind of thing, but it is a different kind of activity. When it comes to thinking about what writers do, universities are really rather hopeless at getting their heads around the fact of this difference; and when it comes to the REF, there is a tendency to evaluate creative works on the same kinds of grounds as learned papers, which is a mistake rooted in a simple kind of category error.

The problem is this: if we take the narrow academic definition of research as our starting point, we have to concede that what writers of fiction and poetry do really isn’t research at all. Of course, when it comes down to it, we writers in universities all argue as hard as we can that what we do is research, because “research” is a shorthand for “writing stuff that matters”; and we like to think that what we write matters—as perhaps it does, to an extent. But at the same time we know that it’s not really research in the way many other people mean it. Here’s what the REF document has to say about research (it’s in Annex C of the REF guidance, if you want to be geeky about it):

1. For the purposes of the REF, research is defined as a process of investigation leading to new insights, effectively shared.

2. It includes work of direct relevance to the needs of commerce, industry, and to the public and voluntary sectors; scholarship; the invention and generation of ideas, images, performances, artefacts including design, where these lead to new or substantially improved insights; and the use of existing knowledge in experimental development to produce new or substantially improved materials, devices, products and processes, including design and construction.

New insights, effectively shared. This sounds nice and broad, as does the generation of ideas, images, performances and artefacts. But the more I think about this, the more I find myself puzzling over it. Do novels lead to “new” or “substantially improved” insights? Now, it strikes me that here there is a difference in the kind of thing that a novel is and the kind of thing that a contribution to scholarship on Emily Dickinson is. The latter exists in a world where knowledge is a public, shared, heap-up-able kind of thing. I write a paper on Emily Dickinson and tooth decay, and I am adding something to a general, public store of knowledge about Emily Dickinson (and specifically about her teeth), a nugget of information that has not existed in the public domain before. This is one kind of new insight. But the kind of insight I get when reading a good novel is a different one. Let’s say I read Saramago’s The Elephant’s Journey. It’s a lovely book about a journey of an elephant from Lisbon to Vienna. I recommend you read it. I gained some insights into elephants, and into Portuguese history. But these insights were not, when it comes down to it, reliable or secure. I’d rather trust an elephant specialist, if I wanted to find out about elephants, than I would trust the notoriously tricksy Saramago. The real insights I gained when reading the book were not heap-up-able, public kinds of things in the way that further data on a poet’s molars might be. Instead they rendered my sense of life slightly different from how it was before I read the book, they were more of the nature of small displacements in the way I attended to the world, small pleasures that I could not have anticipated. Insights effectively shared: yes and no. But substantially improved insights? I think not. Creative writing sits uneasily against these kinds of definitions. We can say that we know incrementally more now about Shakespeare than was known in the time of Dickens; but I don’t think, for example, that we can say that Dickens is incrementally more insightful than was Shakespeare.

So I ask myself: do I do research? On the one hand, yes, of course I do. I’ve been breaking my back learning Chinese for my next novel, and spent the summer two years ago enduring hard seat journeys through China, finding stuff out. I spend weeks tramping round Bulgaria in hiking boots for the novel that is coming out this summer. And my children’s book, The Snorgh and the Sailor, was based upon years of close study of things like soup-making, human grumpiness and bathtubs. So this is, in the broadest sense, research, in that it is a process of investigation and exploration of the world. But if research is seen as a process of making incremental contributions to heap-up-able knowledge, then I can’t help feeling that the process of writing poems and stories is simply not that kind of thing.

Ultimately, I don’t think it is possible to square the circle of fitting what writers do into the definitions of research used today in universities. This problem of squaring creative non-heap-up-able activities with heap-up-able research demands is a problem that may have already been addressed more effectively elsewhere in universities than in creative writing departments, for example by fine art departments; but then, perhaps they have the advantage of not labouring under the misapprehension that fine art—the making of paintings and sculptures and photographs and installations and so on—is simply an aspect of the study of art history in the way that creative writing is seen as an aspect, and a minor one, of the study of english literature. It is worth holding out and arguing, then, for a different notion of research—I hope to talk about this in a future post (hence the “Part I” in the title). But until then, I’ll go on with all of my fellow writers throughout the country, arguing that what I do is something that it really isn’t, so that I can accumulate those hypothetical stars about which we have been taught to care so very much.

July 2, 2012

Woodbrooke Borders and Crossings Conference

Just a quick post from Birmingham, where I’m attending the “Borders and Crossings” conference at Woodbrooke Quaker study centre. The conference stars in the most civilised fashion imaginable with tea and cake from 3pm. I’ll be giving a paper on the Wenxin dialong 文心雕龍 (“Literary mind and the carving of dragons”) and the notion of shensi 神思, often translated as ‘imagination’. I’ve written a blog post with some preliminary reflections over on my blog, The Myriad Things. I’ll post over there again as thoughts occur to me whilst at the conference.

July 1, 2012

Two Tribes of Storytellers

Next week, I’m away in Birmingham at the lovely Woodbrooke Quaker Study Center for their Borders and Crossings/Seuils et Traverses conference on travel writing. I’m not exactly a travel writer myself, although much of my writing—both in fiction and in philosophy—has a preoccupation with crossings, passages, movement and travel; and so I’m hugely looking forward to a week in such wonderful surroundings talking about how, as Rebecca Solnit puts it, stories are travels and travels are stories. I’m hoping that the week will be, in spirit at least, half-conference, half-retreat. It is something—after a busy few months—that I could well do with.

I’ll be giving a paper at the conference called “Imagination as Spirit-Travel: Advice for Writers and Travellers from Sixth Century China” (or something like that—I don’t have my abstract to hand), and I’ll be drawing on the Wenxin diaolong 文心雕龍 to talk about this strange connection between travelling, imagining and writing. Writing, I always think, is a matter of exploring the world, a matter of how you navigate between strangeness and familiarity. It doesn’t matter whether what you explore is close at hand, or whether it is distant: what is crucial is this curiosity, this edge of inquisitiveness, and this passage between what seems familiar and what seems unfamiliar.

One of my favourite essays that talks about this (an essay that, sadly, I won’t have time to talk about in my paper, which I why I’m writing about it here) is Walter Benjamin’s The Storyteller, where he talks about two tribes of storytellers: those who go wandering, and those who prefer to stay put. I’m more in the former tribe, I think; but I know many people more in the latter tribe. And there’s a bit of a prejudice in favour of the latter in creative writing circles. “Write about what you know,” is the usual cliché. I’m not sure that this is good advice, for reasons I’ll return to.

For me, whatever tribe you belong to, it seems that the most interesting work often emerges out of the place where both of these things happen. We are always (even if we don’t leave our sitting room) making new departures; and we are always (even if we are paddling down the Amazon in a canoe) bringing along with us much that stays more or less the same.

Benjamin writes that the archaic type of the wandering storyteller is embodied in the figure of the “trading seamen”, and that of the storyteller who stays put is embodied in the figure of the “resident tiller of the soil”. He goes on to say:

With these tribes, however, as stated above, it is only a matter of basic types. The actual extension of the realm of storytelling in its full historical breadth is inconceivable without the most intimate interpenetration of these two archaic types. Such an interpenetration was achieved particularly by the Middle Ages in their trade structure. The resident master craftsman and the traveling journeymen worked together in the same rooms; and every master had been a traveling journeyman before he settled down in his home town or somewhere else. If peasants and seamen were past masters of storytelling, the artisan class was its university. In it was combined the lore of faraway places, such as a much-traveled man brings home, with the lore of the past, as it best reveals itself to natives of a place.

I love this passage, even if it is a decidedly Romantic view of the past, one that feels rather closer to myth than history. The notion of the workshop where itinerant journeymen and resident craftspeople mingle is a lovely one. It suggests not only that both tendencies are needed, but also that the thing that brings together these two tendencies—the tendency to wander and the tendency to stay put—is craft. Craft means working and reworking. It means long hours and patience. It can even mean facing boredom. Benjamin knows this. Boredom, he says in the same essay, is the dream bird that hatches the egg of experience. It is through the patient application of craft that the raw materials of our writing turn into something substantial. Inventing stuff is relatively easy. Look, I’ve just invented a dinosaur driving a tractor, whilst wearing a Trilby and smoking a Cuban cigar! But the work of the imagination requires more than this. We can pop out eggs all over the place. But to actually incubate the things takes hours of sitting on the nest.

So Benjamin suggests that there are three aspects to storytelling: experience from elsewhere, experience that is close to home and familiar, and craft; and it is craft that integrates our mass of experiences, draws them together, finds the hidden connections and tensions between them, and allows us to fashion them into writing that is worth reading.

There are different craft challenges, I think, depending on which tribe you belong to. The most serious problem faced by storytellers (like me) who like to wander elsewhere is the problem of becoming seduced by surface exoticism. We can assume that because something is unfamiliar, it is interesting. We don’t look deeper into the human significance of what we are seeing, but treat it as a spectacle. When writing about elsewhere, it is not enough to rely on unfamiliarity alone. It’s also a matter of burrowing beneath the surface until you stumble across the homely in the unhomely, the familiar in the unfamiliar, the mundanity that lurks behind the strange. I remember, before I started writing seriously, I was doing anthropological fieldwork in Indonesia—exciting, exotic, distant, malarial—and it struck me one day, as I sat alone with a beer on the jetty at the back of the island’s only hotel (OK, there were two hotels, but the other one was actually a brothel), that behind all this surface exoticism that had so interested me it was just a bunch people doing stuff on a small, remote and not very happy island. People like you or me, getting on with their lives, in difficult circumstances.

When it comes to staying put, however, we have a rather different set of problems. Familiarity may or may not breed contempt, but it certainly can breed inattention. You go on holiday and everything seems vibrant and new and fresh. But back at home, everything seems a bit dull, a but humdrum. It is worth remembering, however, that everywhere is exotic from some point of view. Exotic is a relative term. From where I’m sitting, the Mongolian Steppe might seem to be just the coolest, the most exotic, the most exciting place on earth. But for somebody who has spent their life on the Steppe, there might be nothing more exotic than the East Midlands of the UK where I happen to live. And the East Midlands is exotic. Last week I was in a second-hand bookshop eavesdropping on a conversation with one of Britain’s only professional knife-throwers. Now that’s exotic. But the danger for writers who like to stay put is that of becoming habituated, the danger of the attention being dulled, the danger of falling back on assumptions instead of keeping the attention honed. Assumptions are hard to root out, because they are almost invisible to us. This is obvious when you ask people to draw: they don’t draw what they can see, they draw what they think they can see. To learn how to see the world, we have to unlearn our assumptions about the world, or we risk becoming lazy observers.

This is why I don’t agree with the old “write what you know” schtick. It privileges one tribe over the other; and I’m with Walter here in my view that it is in the craft that mediates between the two tribes that the most intriguing stuff happens. The labour of writing about your home-town and rendering it unfamiliar, and the labour of writing about somebody else’s home-town and rendering it familiar, are equal in extent; and they demand an equally robust application of imagination. And so, whatever tendencies one has as a writer—whether resident tiller of the soil, or trading seaman—in honing one’s craft in the great workshop that is the community of those who write, my advice would not be “write what you know.” Instead it would be this: “get to know about what you are writing about.” And that applies whether what you are writing about distant or whether it is nearby, whether you prefer to set out on distant sea-voyages, or whether you like stay put.

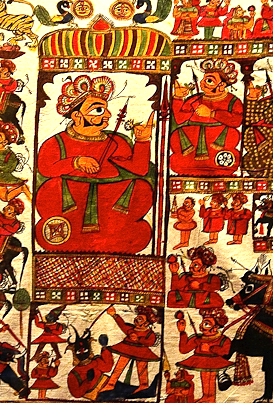

Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons: Pabuji par by Jaravcand Josi of Bhilwara Tropenmuseum – Pabuji-Verteldoek licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic.

June 28, 2012

The Descent of the Descent of the Lyre

I’m delighted to say that my novel, The Descent of the Lyre, is due to be published this summer by Roman Books. It will be available both in the UK and the US. I’ve just published a trailer for the book over on YouTube, and you can see it in action here.

So, now that the book is so close to being published, I thought I’d write a little bit here about the descent of The Descent of the Lyre (you see, the title of this post was not a typo after all).

A long time ago, a friend asked me to write a story “about the guitarist’s hands”. This must have been some time around 1997 or 1998. I thought it would take a week or so, but soon realised that the story was not going to take shape quickly. The idea rattled round my head for years, and there was one striking image that kept haunting me—the image that appears in the book towards the end, where Ivan, the book’s protagonist is discovered in the theatre. It wasn’t until I first went to Bulgaria in 2005 that I felt as if I had a way in to this story, and that I realised that this story would be a novel.

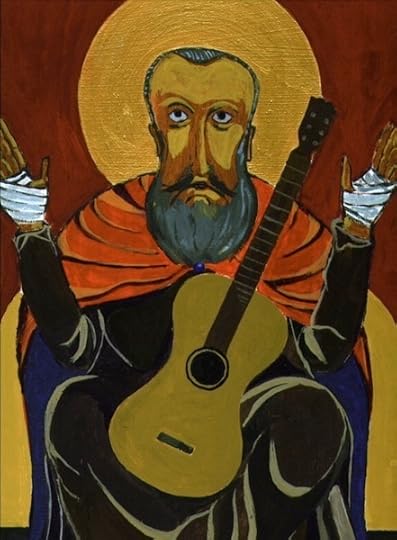

Bulgaria was not the most obvious choice for a novel about the nineteenth century guitar: there is no tradition of guitar music in Bulgaria in the early nineteenth century; but somehow, this is where the story decided to put down roots, and somehow the figure of a Bulgarian saint emerged, a saint, ‘about whom, ‘the lives of the saints, the hagiographies and concordances, the encyclopaedias and church documents, say nothing’, who moves from his home village of Gela, the legendary birthplace of Orpheus, to a life of banditry, exile and suffering. Very early on, I decided to paint an icon of the saint, with a guitar and bandaged hands. Despite the crudeness of the end-result, this image of Ivan Gelski accompanied me through the long process of writing the book. Even as I write this, Saint Ivan is sitting on the shelf, gazing out at me severely…

The Icon of Ivan Gelski – Will Buckingham

The Icon of Ivan Gelski – Will Buckingham

For me, writing is never just about writing. It always involves other, unexpected things. So in 2007, I made an extended research trip through Europe to Bulgaria for the novel, thanks to a generous Arts Council grant. How do you ‘research’ a novel? You go somewhere, and you hang out, and you hope stories will fall into your lap, or some sniffing around you, or surprise you in the dark back-streets like muggers. There’s nothing particularly systematic about it. And so, the process of researching this book was one that took me to some interesting places, from small private guitar museums, to shady Bulgarian bars where they did fantastic shopska salata…

A Bar in Plovdiv, Photo Will Buckingham

A Bar in Plovdiv, Photo Will Buckingham

…to monasteries and chapels up in the mountains.

A Bulgarian Hillside Chapel. Photo Will Buckingham.

A Bulgarian Hillside Chapel. Photo Will Buckingham.

If I hadn’t expected that this story about the guitarist’s hands would lead me to painting icons, neither had I expected that it would require me to actually write any music myself; but a few years into writing the book, I found myself needing to think about what kind of music might be written by a gloomy nineteenth century Spanish guitarist living in Paris who, after hearing some strange and unsettling Bulgarian music in an uneven time signature, decides to give up the guitar in favour of the piano (this is the kind of question that you ask yourself when writing stories). I wanted to be able to hear the music, so I took some chord progressions from Fernando Sor and mixed them up with a deliberately uneasy take on Bulgarian dance rhythms (one-two-three, one-two-three, one-two, one-two-three). This resulted in the following lost piano work by Fernando (or Ferdinand) Sor.

The Barbarian — a 19th century piano piece in an odd time signature.

The Barbarian — a 19th century piano piece in an odd time signature.

If you are a pianist, give it a go. It is rather difficult to play, and very, very strange (but the supposed author in the novel is in a state of some derangement, so that’s fine), and there’s also a wrong note somewhere in those left hand octaves. The score made its way into the final book; the painting, thank goodness, didn’t.

Somehow, all of this has added up to form the story that is The Descent of the Lyre. Looking back, it is a curious trajectory; and in the end, perhaps, what matters now is the book itself, which is launching itself out into the world, and which—however it is received, whether with cheers or complains or chilly and echoing silence—will separate off from these personal obsessions and strange biographical byways, to make its own way in the world.

Copies of The Descent of the Lyre are now available to pre-order.

June 27, 2012

The Descent of the Lyre: Podcast reading and trailer

I’ve just put together a trailer for my forthcoming novel, The Descent of the Lyre, and uploaded it to YouTube. If you are intrigued to know more about the book, then have a listen here.

I’ve also recorded a podcast of the opening section of the book, and this is now up on the Descent of the Lyre page on this site. Just click the “listen” tab at the bottom of the page.

June 23, 2012

On the Dangers of Philosophical Spaghettification

Well, it has been a large job, but the philosophy book is now drafted and ready, more or less, to be sent off to the publishers; and I’m relieved that it is done. The book, which is to be called Levinas, Storytelling and Anti-Storytelling, and which will appear some time next year, takes up some of the themes in my earlier Finding Our Sea-Legs, but perhaps in a rather less free-wheeling fashion. Much of the book is a somewhat close reading of the philosopher Emmanuel Levinas (who was a huge influence on Sea-Legs) as a storyteller and as, at the same time, an anti-storyteller, a thinker who set himself against the telling of stories. It is the closest to a monograph that I’ll ever get, despite a few very un-monograph-like jokes along the way.

Well, it has been a large job, but the philosophy book is now drafted and ready, more or less, to be sent off to the publishers; and I’m relieved that it is done. The book, which is to be called Levinas, Storytelling and Anti-Storytelling, and which will appear some time next year, takes up some of the themes in my earlier Finding Our Sea-Legs, but perhaps in a rather less free-wheeling fashion. Much of the book is a somewhat close reading of the philosopher Emmanuel Levinas (who was a huge influence on Sea-Legs) as a storyteller and as, at the same time, an anti-storyteller, a thinker who set himself against the telling of stories. It is the closest to a monograph that I’ll ever get, despite a few very un-monograph-like jokes along the way.

As a book, this one will probably be for enthusiasts only (what I like to think of as the abridged version, The Snorgh and the Sailor, is more suited to a general audience); but despite the small potential audience, this is material that I’ve been thinking about for the better part of a decade, and throughout this time I’ve found thinking about Levinas immensely enriching and illuminating. My interest in Levinas has not just been an intellectual interest, but something that has had an enormous impact on how I go about leading my own life, not just how I have gone about thinking, but also how I have gone about acting; and for this, I am extraordinarily grateful.

Nevertheless, I’m glad in the end to be moving on to new territories. In many ways, the book feels more like a farewell note to Levinas (and to some of his fellow phenomenologists) than it feels like the initiation into a life of faithful Levinas scholarship. But this always seems the way with me: I’ve followed a curious kind of trajectory over the years from the study of art and art history, to anthropology, to a long engagement that never quite led to a marriage with Buddhism, to phenomenology, to Chinese thought, with large doses of fiction and storytelling along the way; and I’ve never quite persuaded myself to settle down.

I suppose, in the end, that when it comes to thinking, I fear ploughing one single furrow. And it occurs to me now that I am more interested in where I am going to move to next than I am in going over old ground. Particularly when it comes to philosophy, it seems to me that often philosophers are like black holes. They have an enormous gravitational pull. If they argue consistently and determinedly and with a degree of panache, it is hard to resist them. I know people, for example, who have wandered into the depths of the Shwarzwald that is Heidegger’s thinking and who have found themselves still wandering those maze-like Holzwege ten or more years later. I have met courteous, diffident Husserlians who have become so preoccupied with practising their eidetic reductions that it is astonishing that they manage to get dressed in the morning, or eat breakfast, or keep appointments at the opticians. I have stumbled across Levinas scholars who have gone so far beyond the event-horizon that is Otherwise than Being that they emit no further information, only surges of radiation.

I have always feared getting sucked in to any one system of thought, and the philosophical spaghettification that inevitably follows. This is, no doubt, consistent with my fear of weight and my love of lightness. And if philosophers are like black holes, it seems to me that the trick of navigating through philosophical space is finding a course by means of which you can come just close enough to use the gravity-well of any one philosopher to impart further momentum to your travels, but not so close that you fall into the well entirely, never to emerge again. For me, philosophy is at its most exciting, in other words, when it can hurl you outwards on new trajectories, or can precipitate you in new directions…

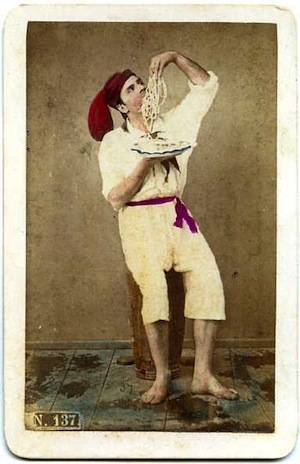

Image: Giorgio Conrad (1827-1889): Spaghetti-eater. Wikimedia Commons

June 20, 2012

The Lady Empress in Brittle Star

Another quick post to say that my story, ‘The Lady Empress’ has just been published in the excellent Brittle Star Magazine #30. Sadly I couldn’t make the launch event down in London last week, but I’ve received my copy through the post, and it’s looking great. The story is a very short piece about a jazz singer, a story which owes something to Billie Holiday.

Will Buckingham's Blog

- Will Buckingham's profile

- 181 followers