Will Buckingham's Blog, page 30

October 3, 2012

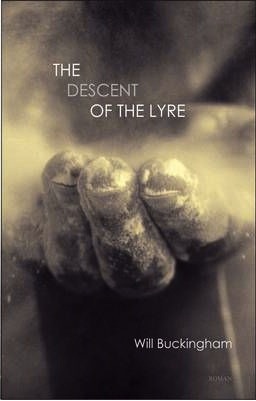

The Descent of the Lyre: GoodReads Giveaway

There are now two copies of The Descent of the Lyre up for grabs in this GoodReads giveaway. You have until the 4th November to sign up for your chance to win yourself a free copy. The Giveaway is open to Goodreads members from the UK, Canada, USA (the book is not due out in the US until 11 December, so you can sneak yourself an advance look if you win) and most European countries. Click the cover or the link below for a chance to win.

Goodreads Book Giveaway

The Descent of the Lyre

by Will Buckingham

Giveaway ends November 04, 2012.

See the giveaway details

at Goodreads.

October 2, 2012

The Snorgh Shortlisted for 2013 Coventry Inspiration Book Awards

Coventry Inspiration Book Award

Coventry Inspiration Book Award

I’m delighted to say that The Snorgh and the Sailor has been shortlisted for the Coventry Inspiration Book Awards, in the ‘What’s the Story?’ category. The award will be decided by public vote in a round of Big Brother-style (I think they mean the reality TV show, not the novel—or, I hope so at least) eliminations. So, if you know any avid young readers, do encourage them to go on over to the Coventry Inspiration Book Awards website, and to vote for their favourite book. You don’t need to be in Coventry to cast a vote!

There are some excellent books on the list, including Oliver Jeffers’ Stuck and John Fardell’s The Day Louis Got Eaten—it’s good to be in such august company. But I’m hoping that the gloomy be-trunked Snorgh, so beautifully brought to life by Thomas Docherty, will stoically drag his bathtub down to the ocean and, the wind ruffling his damp fur, set forth for success.

October 1, 2012

New Facebook Page

Just to say, I’ve now got a new official writer’s page on Facebook, so do go on over and ‘like’ my page if you would like to. The link is http://www.facebook.com/willbuckinghamwriter. I’ll be using the page to post updates about forthcoming publications and such-like.

September 24, 2012

Research, One Couch at a Time

Bulgarian Rugs. Image: Wikimedia Commons

Bulgarian Rugs. Image: Wikimedia Commons

After several years of research, writing and rewriting, my second novel, The Descent of the Lyre, is now finally published by the excellent Roman Books (in the UK at least—if you are in the USA, you will have to wait until December 11th), and it’s good to see that the novel seems to be already getting a few nice reviews here and there. But I thought I’d say a little bit here about the research that led to the book. I’ve written already about research and fiction here on The Myriad Things, and also written some research notes over on Necessary Fiction; but here I want to say more about the research trip that I made back in 2007.

Most of The Descent of the Lyre is set in the Rodopi mountains of Bulgaria and nineteenth century Paris. Early on in the writing of the book, it occurred to me that writing about elsewhere is a perilous process. There are so many ways of getting it wrong, after all. And so as I wrote the book, I did my best to grapple with history, with the Bulgarian language (what progress I made there has, alas, now been almost entirely lost), with Bulgarian history and so forth. But I was also lucky enough to be given a small grant by Arts Council England to travel to Bulgaria overland, for the purposes of research, and so I invested in a pair of sturdy boots (I still have my Arts Council Boots—they’ve held up well), planned my route, and before too long was heading South by train through Paris, Vienna and Bucharest to Sofia and beyond.

I spent eight weeks in all on that research trip, travelling from town to town and village to village, chasing down stories. When it comes to fiction, as I have probably said before, research is, in part, a haphazard process: it involves remaining open to whatever kinds of stories you happen to stumble across, keeping your ears pricked, following your nose. Researching fiction pulls in two directions: on the one hand there is the proliferation of tales and stories, and on the other hand there is the effort to sort out these threads, to disentangle them sufficiently to be able to knit together something of a story of your own.

My budget was small, and eight weeks is a long time to travel, but fortunately I had, the year before, signed up with CouchSurfing.org, which is—for those who haven’t heard of it—a global hospitality network. It is a strange and wonderful thing: a network of people who are willing to open their homes to strangers for free, a community based on the principles of hospitality; and having hosted a number of people back in the UK and found the experience fascinating and enriching, I set out on my researches for my novel, heading across Europe on a shoestring, one couch at a time.

This was not, however, simply a matter of economics—although I could not have afforded to stretch the research out to two months without CouchSurfing. It was also about friendship—I am still in touch with many of the friends I made on that trip, people who I ate and drank with, who I shared journeys with, who I talked with far into the night—and it was about gaining the kind of understanding of place that you simply cannot have if you flit from one hotel to another. I remember one night in particular, at the end of my stay in Bulgaria, when I was taken out by friends to a bar, and where over more beers and mastikas than I can recall, some of my Bulgarian friends and former CouchSurfing hosts interrogated me in forensic detail about the story, checking it point by point, until they were happy that I was going home with something more or less watertight. I am hugely grateful to them for the pains they took.

To the extent that The Descent of the Lyre has successfully managed to speak about the elsewhere that is Bulgaria and that is, to those who live there, home, I owe this to the friends that I made along the way (to the extent that it has been unsuccessful—and I have a few Bulgarian friends reading the finished novel at the moment, so I’m waiting anxiously for their verdicts—I am responsible, of course, for any shortcomings). For eight weeks, I discussed the story endlessly with my various CouchSurfing hosts, putting twists on it here and there, scrubbing out plot-lines because they didn’t work, fashioning and refashioning the tale; and by the time I caught the train home, through Budapest, Vienna and Paris, I had the skeleton of a story, a story that would still take several more years to hone into a novel, but one in which I could be relatively confident.

My instincts as a storyteller are always towards the fable, the ‘told tale’ that is shared around a table, the stories that are passed from mouth to mouth; and so perhaps it was fitting that it was as a guest in many houses that this novel took shape. I am certain that, without CouchSurfing, it would have turned out to be a different—and, perhaps, a less rich—book; and whilst I do not have any immediate plans for further extended research trips, when I do get round to the next big researched novel, I’ll be putting on my Arts Council Boots again, shunning expensive hotels, and knocking once more on the doors of complete strangers…

The Descent of the Lyre is now available in the UK and for pre-order in the USA.

September 17, 2012

Review of “The Descent of the Lyre” on Tasting Rhubarb

I’m very pleased to have received a lovely review of my second novel, The Descent of the Lyre over on Jean Morris’s wonderful Tasting Rhubarb blog. Here’s an extract from the review:

You find yourself admiring this book very much: the fluid, flowing prose and fierce, colourful historical detail… This stark, sad story somehow makes you feel a bit better about life, but not in any way that’s false or facile. It’s different from anything you’ve read in ages, and a fine, humane, intelligent work.

The full review can be found by going here.

September 15, 2012

The Lyre & the Leicester Mercury

Just a quick post to say that there’s a nice little article in the Leicester Mercury about my new novel, The Descent of the Lyre in the Leicester Mercury. To have a read, go here.

September 8, 2012

Understanding, misunderstanding and failing to understanding the classics

Japanese image of the mythical bird Peng 鵬, who transforms into the fish Kun 鲲. Image Wikimedia Commons.

Japanese image of the mythical bird Peng 鵬, who transforms into the fish Kun 鲲. Image Wikimedia Commons.

I’m writing this from Bangor, where I’m at a conference on Cultural Translation and East Asia; and in about an hour’s time, I’ll be in a panel where I’ll talking about the Chinese classic the Yijing 易經 (I Ching) and about my novel-in-progress, A Book of Changes, which puts the Yijing to work as a kind of literature machine, giving rise to one story for each of the sixty-four chapters of the Chinese text. As I need to hurtle off and give my paper, this post will be necessarily brief.

As a linguist of only middling powers, I’m intrigued by questions of mis-translation, this being something I’m guilty of almost every day. I’m interested in the grains of indeterminacy that creep in when you translate between cultures and settings, and more broadly I am interested in the role of misunderstanding and non-understanding in the way that we relate to, and understand, the world.

After seven years of working with the Yijing on this curious literary project, I would still hesitate to say that I understand the text. I would be suspicious of anybody who claimed that they did, as if the Yijing had a single core of meaning that could be sought out by sustained reflection, study or meditation. In my failure to understand, I am in some ways similar to many Chinese readers of the text: it is very common for Chinese readers to say to me things like, ‘You are writing about the Yijing? Wow. When I was younger, I read the book over and over, but didn’t understand any of it…’

However, I am not sure that a Chinese reader failing to understand the text is failing to understand it in quite the same way that I, as a reader, am failing to understand. So the question that I’m starting my paper with is this: are all failures to understand equivalent?

This interests me because the failure to understand, or the sense one has that one has somehow failed to understand, is also a particular kind of relationship with the thing that one is failing to understand. An accomplished mathematician failing to understand a complex equation is not doing the same thing as I (with my basic algebra) am doing when I fail to understand the equation. Our relationships with the complex set of symbols on the page are utterly different. And when I read the Yijing now, I fail to understand it in a richer, more complex (but also more constrained, perhaps) way than I did before I set out on the path of learning Chinese, reading, studying, and writing these curious stories based on the Book of Changes.

One reason for the continuing fascination of the Yijing, perhaps, is that it is a book that has been constructed (or that has evolved) to be somehow inherently refractory to understanding; and that this is what leads to its considerable richness in its capacity to give rise to new thoughts. As twelfth century poet, diviner, philosopher and general good sort, Yang Wanli 楊萬里 once said — and I think I’ve quoted this before — “the profound implications of the Book of Changes are what plunges people of the world into doubts and makes them think” (quoted in Ming Dong Gu’s Chinese Theories of Reading and Writing). Or, to put it differently, non-understand and doubt can give rise to a degree of cognitive flexibility.

Anyway, I’m going to be talking about all of this by means of curious stories about fish that transform into birds, three-legged-crows, obsessive ichthyologists and such-like. And I’m very much hoping that my audience will do me the service of failing to understand what I’m talking about in all kinds of interesting ways…

Cultural Translation and East Asia.

This weekend I’m at the Cultural Translation and East Asia conference in Bangor (link here) — a friendly gathering of China, Japan and Korea scholars working in film, literature, language and other areas. I’ll be reading a paper called Telling Tales about the Yijing which is about, amongst other things, three legged crows (三足烏) mythical fish, the art of looking at water (this comes from Mencius, and one of my favourite lines, 觀水有術, “there is an art to looking at water”) and how it is not the same thing for me to fail to understand the Yijing as it is for a Chinese reader to fail to understand the Yijing. The paper may see the light of day in a different form, and if so, I’ll post here when it does.

September 4, 2012

The Descent of the Lyre Now Published (an interview)

The Descent of the Lyre. Will Buckingham 2012. Published by Roman Books.

The Descent of the Lyre. Will Buckingham 2012. Published by Roman Books.

Well, I’m pleased to say that my second novel, The Descent of the Lyre, is now published, and so I thought in honour of the occasion I would post the following interview that first saw the light of day over on Necessary Fiction.

The interview that follows was conducted by my one and only pseudonym (or perhaps my heteronym), Lupe Varos. I invented Varos back in 2006, when I was running a small literary magazine and, not having enough content, decided to publish one of my stories under a pseudonym. Back then, Varos was based in the Atlas mountains of Morocco, where he was working as an English teacher. Now, by an astonishing stroke of luck, I have tracked him down to where he is currently living, and it happens to be in the Rodopi mountains of Bulgaria, which is precisely where the Lyre is set. Where would the world of fiction be without such remarkable coincidences? And Varos has kindly offered to interview me. It’s all very postmodern, don’t you know…

The following interview was conducted by fax, as Varos does not use email. He’s funny that way. We faxed and refaxed drafts of the interview between Bulgaria and the UK until we were both happy with the text. It was an arduous process, but worth it in the end, I think.

+

LV: Your new novel is set in the Rodopi mountains, which happens to now be my home. What is the novel about, and why set a novel here?

WB: I think I first visited the Rhodopes in 2005—whilst you were in Morocco, if my memory serves me right—for a short break, and I was immediately struck by the rich relationship there is here between landscape, memory, myth and music. It’s an extraordinary part of the world. Whilst on that first trip, I visited Gela, which is said to be the home village of Orpheus, as well as the Devil’s Throat cave, where the ancient musician is said to have entered the underworld. I was intrigued enough to come back to Bulgaria the year after, and then the year after that.

LV: Three trips?

WB: Indeed. The first was a holiday although, as a writer, I don’t really think of holidays as holidays: I’m always on the lookout for new stories, thoughts and possibilities. The second was a short trip. I was attending a philosophy conference at Sofia University St. Kliment Ohridski, and so I took a few extra days to travel in the country. Then the third trip was a more extended journey, in 2007, across Europe by train, which was specifically for the purposes of researching the book.

LV: Was it a conference about Bulgarian philosophy?

WB: No. French/Lithuanian. Emmanuel Levinas. It was the one hundredth anniversary of his birth. I remember lots of very long papers, simultaneously translated. It was a kind of asceticism.

LV: Let’s get back to Orpheus. You say that your novel The Descent of the Lyre is a reinvention of the myths of Orpheus. In what way?

WB: I am a classical guitarist, and so the Orpheus myth is one that has long had a resonance for me. What strikes me about the tale of Orpheus—and about the related Greek myths—is how it combines an extraordinary violence, a sense of loss and longing, a concern with religion, and a preoccupation with music as both that which is born out of violence, and that which might allow violence to be stilled. It seems to be a myth, in other words, that has what Lorca calls “duende”.

As a reinvention, these components are still there in the book, but shuffled around somewhat, so that the book touches on the myth repeatedly without following exactly the same kind of trajectory.

LV: We’re getting very abstract. How about stopping all that philosophy for a moment and telling me what the book is about?

WB: Well, you were the one who asked about philosophy… but, OK. Point taken. The book follows the fortunes of Ivan Gelski—Ivan of Gela—who leaves his village after the abduction of his bride-to-be and becomes a haidut.

LV: A bandit?

WB: Exactly. This is the early nineteenth century. Ivan Gelski takes to the hills, where he leads a small band of marauders, seeking revenge for his stolen bride. But things change when his companions abduct a Jewish guitarist, who plays extraordinary music that manages to still Ivan’s hunger for vengeance.

LV: Wait a minute—what’s a Jewish guitarist doing in the Rodopi mountains in the early nineteenth century?

WB: Well, it’s a complex story; but the Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II was engaged at the time in the reform of Turkish music—there’s quite a long and intricate history of musical cross-fertilisation between the Ottoman empire and Europe, and all of this is touched on in the book, but perhaps it is a little too intricate to go into here. Anyway, this is why the guitarist, Solomon Kuretic, was heading to Constantinople. The rest is history. Or, perhaps, fiction.

LV: As the book proceeds, Ivan himself turns to the guitar.

WB: Yes. I don’t want to give the whole story away, but the encounter with Solomon is central to the whole novel. It is what precipitates Ivan on a course that leads to his fame and later to a strange kind of sainthood.

LV: Religion seems to be one of your preoccupations, not just here but in other things you have written as well…

WB: Yes. What can I say? As an atheist child of the clergy (there are lots of us out there), religion is inescapable for me.

LV: So you are a spiritual writer, or a writer concerned with the spiritual?

WB: Good heavens, no! I find the language of “spirituality” oddly enervating. I have no taste for it. Lots of people talk about being “spiritual but not religious.” If anything, I am the opposite: religious without being spiritual. That’s not to say that I have religious beliefs; but I am fascinated by religion. Religion, for me, is a matter of magnificent frocks and cassocks; it is the music of gongs, bells, guitars, choirs and so forth; it is strange rituals and wonderful buildings and peculiar societies of oddball individuals; it is a multitude of experiments in living, some relatively sensible, some utterly bizarre; and it is a huge and fertile mass of stories. Compared with all this stuff, the airy nothings of the “spiritual” seem unappealing to me.

LV: You talk about ‘stuff’: is this some kind of materialist view of religion?

WB: Yes, but with the qualification that stuff is wondrous and exciting and rich and strange, rather than heavy and lumpen and empty of meaning. Sometimes I think I’m not so much a materialist as a “thing-ist”. I like things.

LV: So how does this play out in the book?

WB: Well, in a few ways. For example, there’s a character called Bogdan who loves only those things he can touch, those things he can feel with his hands. I’m rather fond of Bogdan’s approach to things. In terms of the apparently “religious” dimensions of the book, the story begins with a curious evocation of a visit to a hillside chapel, and an encounter with a saint with a guitar and bandaged hands. This might seem as if it is setting the book up as somehow “spiritual”; however I think by the end it is clear that something else is going on. Nevertheless, this image of the saint becomes the guiding image for the book, although by the book’s end, despite all the miracles and strange happenings, I think I haven’t departed too far from the kind of “religious but not spiritual” thing-ism that interests me.

LV: Does the chapel exist? I’d like to visit it.

WB: Yes, it does. It’s not far from the monastery at Bachkovo. Just up the hill, in fact.

LV: Oh, that’s pretty close. I might go and visit when I have a spare moment. And what about the saint?

WB: So you mean does he exist? Well, he does now. Before I started to write the book, I decided to paint an icon of him, to give me a sense of what I was writing about. I’ll let you see the image, although I should warn you that—despite four years in art college—I’m far from being a decent artist.

The Icon of Ivan Gelski – Will Buckingham

The Icon of Ivan Gelski – Will Buckingham

LV: That’s a strange image.

WB: Indeed. Strange, and not very well-painted.

LV: What were you doing for those four years in art college if you were not learning to paint?

WB: That’s a very good question. I was mainly hiding away and reading books. It was a good education.

LV: OK. Let me get back to the question of stories and storytelling. You say that one of the reasons for your fascination with religion is that religion involves a seething mass of stories.

WB: Yes. I’m excessively preoccupied with stories. I work in both fiction and philosophy, and I like to think that what I do can be divided into two kinds of activity. On the one hand, I am concerned with story-like philosophies. And on the other hand, I write philosophical stories. This doesn’t mean that I shoehorn Kant into everything I write, of course (although jokes about Kant are always welcome in novels), but it does mean that everything I do seems to come from one or other—or both—of these directions.

LV: I’d like to hear more about your relationship with the guitar. You have been playing for—how long?

WB: About thirty years. On and off, of course. When I was at school, I used to get up early in the morning, around six, and practice for an hour or two. Every day, without fail. I was very committed. I did that for about seven years. Sometimes back then I thought I might become a professional guitarist. But I neither had the fingernails nor the determination. I play less these days, and I’m very rusty; but guitar music has been an important part of my life. It’s an extraordinarily intimate instrument, I think.

LV: In the book, one of your characters starts to write a history of the guitar, also called The Descent of the Lyre, which begins by making a link between the guitar and violence. What is this link?

WB: Well, it’s there in the myths of Hermes creating the lyre. It’s there in the tales of Orpheus. And it’s there in Lorca as well, of course: both in his poetry, and in his life as well, I think.

LV: In the book there are a number of recognisable historical characters: Fernando Sor the guitarist; Antoine Meissonnier the publisher and composer; Karl Toepfer the guitarist and philosopher; Félicité Hullin the dancer. How did you research the book?

WB: Fairly meticulously, I hope. There were the three trips to Bulgaria. I also spent time in Paris and Vienna. The UK Arts Council funded the final research trip, which was invaluable. I bought some very solid boots with a part of the grant, so that I could tramp over hillsides. They were excellent boots. That was five years ago, and I am still wearing them today. I did a fair amount of archival research as well, because it is important to get things right; but I didn’t need any special footwear for that bit.

For me, writing fiction is a kind of research. It is a testing out of ideas in relation to the wider world. It is a kind of exploration. If my writing stopped feeling exploratory, I’d stop writing, which is why my books are all rather different from each other. One of the biggest challenges with The Descent of the Lyre was making sure that the story I was telling was one that was in harmony with the actual historical events. I drew a lot of time-lines. But—no doubt—there will be mistakes. There are always mistakes.

Getting to grips, even ever so slightly, with the language certainly helped. Back in 2007, when I carried out much of the research, I spoke at least some Bulgarian, although it’s currently been pushed out of the way by the Chinese I am learning for another project, so I’ve forgotten most of it, or else when I remember it I stick bits of Chinese in, which leads to terrible confusion.

There were other kinds of research too. Painting the icon was a kind of research, as was the few days that I spent writing an imaginary lost musical work of Fernando Sor. The score for this piece actually appears in final version of the book (although I only realised after the last proofs had gone off that I had included the wrong draft of the score — something that will matter only to sharp-eyed musical purists…).

LV: The Descent of the Lyre is out now. Are you working on anything else at the moment?

WB: Well, there’s a philosophy book that is for enthusiasts only, called Levinas, Storytelling and Anti-Storytelling. Then there’s my children’s book, The Snorgh and the Sailor which is just out, and seems to be doing well, so I’m wondering about working more in that particular world. I have a couple of projects in the area of children’s writing that I am following up on. And I’m also doing a book of stories – a ‘novel of sorts’, I am calling it – based around the Yijing or Chinese Book of Changes, hence the Chinese-learning. This has been fascinating, although it’s a curious hybrid of a book, so who knows who will publish it. In fact, it contains one of your stories.

LV: One of mine?

WB: Yes—that one about the apple pie and the old woman that I published back in 2006 or so.

LV: It would have been polite to ask permission first.

WB: Yes, I know. But you are very hard to track down.

LV: Fair enough. Let me finish by asking you about Bulgaria, which—as you know—is now my home. Are you planning to return any time soon?

WB: Is that an invite?

LV: You’d be welcome any time. Life here is good. At this very moment, I’m looking out over the hillside, a glass of rakiya in my hand, a shopska salata in front of me…

WB: Well, I’d love to, of course. It would be good to blow the cobwebs off my poor Bulgarian language, and I have friends in Bulgaria who it would be good to catch up with. Perhaps if the book is translated into Bulgarian, I can come over for a launch.

LV: If you do that, I will interview you in the flesh. No faxes.

WB: That would be wonderful!

LV: Well, let’s see what happens…

September 3, 2012

The Descent of the Lyre: now out in hardback

I’m delighted to say that my novel, The Descent of the Lyre, is now out in hardback and available to buy. The novel, a reinvention of sorts of the myth of Orpheus, is set in Bulgaria and Paris in the nineteenth century, and traces the history of the guitarist-saint Ivan Gelski, Ivan of Gela. Find out more about the novel here, or watch the trailer below.

Will Buckingham's Blog

- Will Buckingham's profile

- 181 followers