Will Buckingham's Blog, page 26

March 11, 2013

Knowledge and Friendship at the End of the World

The following post was first published on WillBuckingham.com. From time to time, I’ll be republishing essays that disappeared from my old website when I switched over from Textpattern to WordPress a year or so back. The post had its origins in a paper that I gave at a conference on the apocalypse in literature at Westminster University in 2011.

When it comes to the ways that we think about the apocalypse, we are often inclined to moralise the end of the world. From Noah’s flood, to zombie apocalypses caused by the hubris of scientists, to the various kinds of environmental disasters that may or may not face us, our stories about the end of the world often have the distinct air of moral retribution for past misdemeanours. But there are certain kinds of apocalypse – amongst which can be numbered apocalypse by comet – that have nothing to do with blame and responsibility, nothing to do with how virtuous we are or not. These are endings that simply are, or at least that might be.

While it should be said that there’s no evidence that there is a comet heading our way, at the same time, there is no evidence that there isn’t. On their website, NASA point out only somewhat reassuringly that “None of the asteroids or comets discovered so far is on a collision course with Earth. However, we can’t speak for those that are not yet discovered. In principle, one of those could hit any time, but statistically the chances are very small.” And this is an unsettling thought. So what do we do with the idea of an apocalypse that we cannot evade, but for which we are not in any way responsible? How do we respond to the idea of a non-moral apocalypse?

There is just such an apocalypse in Tove Jansson’s 1946 book, Comet in Moominland. For those who are unfamiliar with Jansson’s work, the story goes more or less like this. One day, a comet appears in the sky over Moominvalley. A small troll called Moomintroll and his friend Sniff set off to the Lonely Mountains to speak with the learned astronomers and to find out what is happening. On the way, they meet up with the wandering harmonica-playing tramp, Snufkin, and together they eventually make it to the mountains to discover that there is nothing that they can do, and that the comet will probably hit the earth, specifically in the middle of Moominvalley, “on the seventh of October at 8.42pm. Possibly four seconds later.” They make their way home, through a world that is increasingly unsettled by the onrush of the comet. On their return, they find that Moominmamma has baked them a cake. And so the moomin-family and their friends take refuge in a cave, and there they feast on cake. The comet arrives, and it passes on its way, just brushing the earth with its tail. The sea returns, the sun rises, life goes on.

One thing that is immediately striking about Jansson’s story is that there is very little suggestion throughout that anybody can do anything about this particular end of the world. The astronomers know that nothing can be done – although as good scientists they say that they will note down with interest what happens. Moomintroll, Sniff and Snufkin come away from the observatory knowing little more than the timing of the apocalypse. However, the story is far from being fatalistic. If there is a kind of fatalism in the story, this fatalism belongs to a musk-rat philosopher who appears at the beginning of the story and describes his vocation as sitting and thinking about how unnecessary everything is. Almost immediately, it becomes apparent that this is more or less a pose, and one in which the philosopher himself doesn’t fully believe. When he is offered a glass of wine, the philosopher replies, “Wine, I am bound to say, is unnecessary, but a small drop nevertheless would not be unwelcome.” Indeed, the philosopher clearly has preferences – for wine, for cake, for the avoidance of the apocalypse – but still he holds to his philosophical position that “It is all the same to a person who knows everything is unnecessary.”

Instead of seeking to divert the comet or to prevent the end of the world, and instead of falling into philosophical despair, Moomintroll and his family and friends take another course, one that – if I was to give it a name, I would perhaps call Epicurean or Lucretian, because it reflects two themes that appear in the work of the Greek philosopher Epicurus and his Roman follower Lucretius. The first theme is that of knowledge, and the second is that of friendship. Epicurus (unlike, for example, Plato), believed that there was a value in studying celestial phenomena such as comets; but he believed that this was worthwhile for an interesting reason. If we look up to the skies and fail to understand them, Epicurus maintained that we can be caught up in all kinds of human-made stories that cause us misery and unhappiness. We spin astrologies, stories about the baleful influence of the planets, tales of divine retribution and so on. So the study of the natural sciences leads to the dissolution of stories that cause us various forms of paranoid misery. Knowledge, in the Epicurean system, is a good thing not just because it can help us solve problems, but also because fear is often rooted in a lack of knowledge. There’s a nice example of this in Jansson’s book. Towards the end of the story, the returning party comes across a group of hurrying refugees.

‘It’s strange,’ said Moomintroll, ‘but it seems to me that we aren’t as afraid as any of these people, although we’re going to the most dangerous place of all, and they’re leaving it.’

‘That’s because we are so extremely brave,’ said Sniff.

‘H’m,’ said Moomintroll. ‘I think it must be because we’ve sort of got to know the comet. We were the first ones to find out that it was coming. We’ve seen it grow from a tiny dot to a great sun… How lonely it must be up there, with everybody afraid of it!’

The relative freedom from fear here comes from dissolving the fantasy that the natural world is out to get us. In her approach to knowledge, Jansson provides us with middle way between two extremes. On the one extreme there is the musk-rat philosopher, committed to the uselessness of everything; but on the other extreme there is the unreasonable belief that we are omnicompetent, that we are capable of resolving all the problems with which we are faced. Jansson reminds us that, for all our knowledge, there are some kinds of apocalypse that no amount of human ingenuity will overcome; but she also reminds us that knowledge is still worthwhile, above and beyond its practical application, above and beyond questions of use or uselessness.

But there’s a second Epicurean or Lucretian theme in this passage, and that is friendship. I think of friendship in this sense as a kind of accommodation not only to each other, but also to the world. Moomintroll comes, by means of knowledge, to feel a kind of kinship with the comet, whilst still knowing it may very well destroy them. The moomin books as a whole are pervaded by a strong sense of the value of this kind of generous accommodation, not only to the facts of nature, but to each other. The musk-rat may not be the most congenial of characters, but he is nevertheless welcomed into the Moominhouse and given a glass of wine and treated as a member of the family. The various quirky creatures who come and go through moominvalley in the various books are all treated with generosity, hospitality and an understanding that their various quirks are – like comets – simply facts of life.

So Moomintroll, Sniff, Snufkin and their companions arrived back from the Lonely Mountains to find Moominmamma spending what may be the final hours of the world, “peacefully baking bread and cakes.” Because even if the world is ending, there is still much to be said for the baking and sharing a good cake. The image in the penultimate chapter of a group of small creatures sitting in a cave, eating cake (slightly squashed, because the musk-rat has sat on it – what can you do with philosophers?), huddled together in friendship, and waiting to see if the end is nigh, could be pathetic, or absurd, or deeply satirical; but my sense is that there is a much more robust philosophical response here to the possibility of an apocalypse that we cannot evade. The apocalypse may, or may not, be upon us; and there may or may not be anything that we can do about it. We should, of course, do what we can to avoid those things that can be avoided. But for those other possibilities about which nothing can be done, we can at least – in the time that we have here, in the time that remains to us – do all we can to cultivate the knowledge and the friendship that may make life truly worth living.

I am reminded here me of the poem by the novelist and poet Julia Darling that I found one wintery autumn day, on a postcard in the Rendezvous Café in Whitley Bay on the North-East coast. Already diagnosed with the cancer that was eventually to kill her, Darling sat one day in the very same café that we sat, looking out over the grey swell of the North Sea, and wrote the following words:

Come eat strawberry flan

while we can, while we can.

March 9, 2013

A brief note on knowledge in the hands

Some time ago, in a post on learning Chinese and the Bulgarian bagpipes, I wrote about the notion of concepts expressed in the hands, about the way in which learning a new skill—whether speaking Chinese or playing the bagpipes—goes beyond the acquisition of information, and instead involves the formation of particular kinds of bodily habit. Some time after writing that, I came across the following snippet from Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology of Perception, and I thought that it was worth sharing here. Here’s the quote:

To get used to a hat, a car or a stick is to be transplanted into them, or conversely, to incorporate them into the bulk of our own body… It is possible to know how to type without being able to say where the letters which make the words are to be found on the banks of keys. To know how to type is not, then, to know the place of each letter among the keys, nor even to have acquired a conditioned reflect for each one, which is set in motion by the letter as it comes before our eye. If habit is neither a form of knowledge nor an involuntary action, what then is it? It is knowledge in the hands, which is forthcoming only when bodily effort is made, and cannot be formulated in detachment from that effort (166)

March 8, 2013

Review in Soundboard Magazine

This is just a quick post to say that The Descent of the Lyre has had a wonderful little review in the US Guitar Foundation’s excellent Soundboard magazine. Here’s a quick extract:

The author has a deft touch with imagery and color, helping to evoke the times and places. The chapters are quite short, so it’s easy to read just one more, and then maybe another, and …There are very few novels whose protagonists are classical guitarists (Like a River of Lions by Tana de Gámez is perhaps the best-known example), and it’s a pleasure to report that this one is a most enjoyable read (especially if you’re a guitarist).

March 7, 2013

Isaac’s Gift

Just a quick email to say that I’ve got a new article online over on Aeon Magazine’s excellent website. The article is about the Tanimbar islands in Indonesia, adat ritual law, gift exchange, and talking lizards.

You can find the link here. Whilst you are at it, it’s worth signing up for Aeon’s RSS feed: they publish a new (and excellent) article every weekday.

Isaac’s Gift

Photo by Doug Meikle Dreaming Track Images

Photo by Doug Meikle Dreaming Track Images

If you have not yet come across the wonderful Aeon Magazine — a repository of fascinating thinking and excellent writing by an array of great writers— then it’s time that you paid them a visit. This is what they say on their website:

Aeon is a new digital magazine of ideas and culture, publishing an original essay every weekday.

We set out to invigorate conversations about worldviews, commissioning fine writers in a range of genres, including memoir, science and social reportage.

Aeon has a cosmopolitan outlook, open to diverse perspectives and commited to progressive social change. We have a high regard for science and other empirical knowledge, but also for imagination and personal experience.

Aeon has a conversational ethos, encouraging frank debate in an atmosphere of generosity and open-mindedness.

I’m delighted to say that I ‘ve got a piece over there—published today—on the Tanimbar islands in Indonesia, adat ritual law, gift exchange, and the art of sculpture. You can find the link to the article here. And while you are at it, do subscribe to the Aeon Magazine RSS feed.

Begin afresh, afresh, afresh

Well, it’s now more or less spring; and with the surging green buds etc., I thought I’d give TheMyriadThings a new look. After a few days of burrowing away behind the scenes, I’m just about ready to put the site back online. There are still a few rough edges (if you find any, then let me know), but I’ve simplified things considerably. Now the posts here are divided into three categories. There are essays, which are anything from, say, six hundred words or up; then there are snippets, which are any other bits and pieces that take my fancy but that don’t really merit further development, or that I might one day develop if I have time to do so. Finally there are news posts, which are about what I’m up to, or about what’s going on with the site. This is a somewhat loose and baggy categorisation, but it should be useful to separate out the longer-form pieces from the snappier ones.

Hopefully the new-look site is a bit tidier and brighter than before. There should be a few interesting posts coming up in the next few days and weeks, including some lost posts from an earlier draft of WillBuckingham.com, my personal website. I hope you enjoy the new site, and do let me know if there are any problems. Thanks for your patience whilst the site has been offline.

March 4, 2013

A Few Small Changes

It’s been a bit quiet here of late, as I’ve been busy writing other things; but this is just an advance warning that I’m planning to give TheMyriadThings a bit of a rejig over the next few days. I’ve fallen by happenstance into writing rather long essays here, which is fine: but I don’t want to only write long essays, as the fear of having to write at length could (given that I seem to be somewhat busy at the moment) prevent me from writing at all… So over the next few days, I’m going to give the site a new look, and to re-tailor it so that I can post—as well as longer and more essayistic pieces—various snippets, speculations and other sideshows that take my fancy.

This will mean that the blog may disappear for a few days, with a holding page in place whilst I tinker behind the scenes; but don’t fear, it will be back in action very soon!

March 1, 2013

A Busy Day at Cultural eXchanges

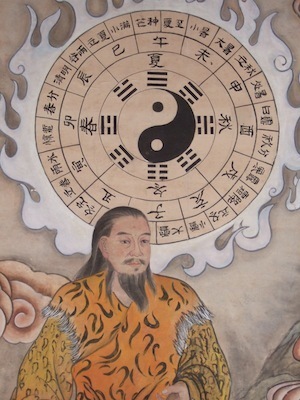

It’s the last day of the DMU Cultural eXchanges festival, and I’m involved in a couple of events. First, I’ll be doing a session on the Yijing/I Ching/易經 and literature with the poet Alan Baker (details here). This event is between 2pm and 3pm in the Clephan Building. And secondly I’m involved in the Leicester launch of the short story anthology Overheard, edited by Jonathan Taylor. The latter event is between 6pm and 7pm, and is also free. A busy day, then, which is why I should stop writing here and get a move on… Come along to either or both of these events if you can make it.

February 23, 2013

Talkin’ ’bout the Yijing (I Ching) — with Alan Baker

I’m hugely looking forward to next Friday, when I’ll be at the Cultural eXchanges festival in Leicester, talking with poet Alan Baker about the Yijing 易經, or Book of Changes. We’ll both be reading from our work that draws upon this, one of the strangest of all strange books in existence, and talking about the Yijing‘s influence on our work. The event is on Friday 1st March at 2pm, and is free of charge.

You can book a place here.

February 14, 2013

The Descent of the Lyre in Bulgarian

This is just a very quick post to say that I’m delighted to have signed a contract with Enthusiast publishing house in Bulgaria for a Bulgarian translation of my novel, The Descent of the Lyre. The Bulgarian version will be coming out some time in the next eighteen months. It feels particularly significant for me personally because, whilst I was writing the book, I was aiming to write something about a world very different from my own, but in a way that would be sufficiently convincing for Bulgarian readers; and back then, I remember thinking to myself that if it made it into a Bulgarian translation, I could be confident that I had not done too bad a job of that perilous business of straying into other people’s histories and myths. I’ll post more here when the book appears in Bulgarian.

On a related note, for those visitors to this website who are down in London, tomorrow evening (15th February) I’m doing an evening event where I’ll be talking about and reading from the book, as well as playing music for classical guitar, down at the Bulgarian Cultural Institute. There’s more information here.

Will Buckingham's Blog

- Will Buckingham's profile

- 181 followers