Will Buckingham's Blog, page 28

December 21, 2012

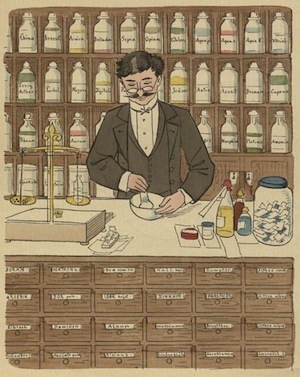

Therapeutic Philosophy and the Pharmacopoeia of Humankind

Was soll ich werden? by Lothar Meggendorfer, 1888: Wikimedia Commons

Was soll ich werden? by Lothar Meggendorfer, 1888: Wikimedia Commons

Some time ago, I attended a conference — I won’t say where the conference was — at which a certain speaker was talking about what he called the “fundamental conditions of human existence”. The speaker was a tall, rather distinguished looking Norwegian academic; and as he spoke, he laid out what he believed these conditions to be. “Existential loneliness,” he said. “Consciousness of impending mortality. Exposure to the terror of existence…” At the end of the paper, there was a chance for questions. I raised my hand. But unfortunately, time being limited, and I didn’t get a chance to ask my question; and what with one thing and another, I didn’t get round to asking the speaker in person. The question, however, has stayed with me; and so I’ll raise is here instead. The question is this: are these things — existential loneliness, consciousness of impending mortality, terror, exposure, etc. — the fundamental conditions of human existence, or are they instead the fundamental conditions of Norwegian existence?

It may seem as if this was not an entirely serious question; but, in one sense, it was a wholly serious question, because, as I was listening to this paper, I couldn’t help finding myself wondering quite how fundamental these conditions were, or wondering whose existence the philosopher was talking about. Did this apply to all of us? Why didn’t I recognise myself in this diagnosis? Would it, in fact, have made a difference if I was Norwegian?

In is true, of course, that we are all born, we all go about our lives with the various drives and impulses that come with being human, and we all die: these are things that unite us all. But the trouble with the notion of “the human condition” is not only that the authorities are really not agreed on what this condition might be, but also that this condition is more often than not seen as something that ails us, and those who like to talk about the fundamental conditions of existence often present themselves as diagnosticians of the sickness that is human life.

The notion of philosophy as diagnosis and as therapy is one that has a long and distinguished pedigree. This is something I’ve been thinking about a lot lately, in part because questions of health and sickness have been very much on my mind. As recently as a month ago, my partner was diagnosed with breast cancer; and if I have been relatively quiet on this blog, it is because I have been preoccupied with matters of more pressing importance elsewhere. For much of the last month, we have been thinking hard about health and about sickness, trying to work out the implications of the diagnosis, becoming familiar with medical processes and procedures and with the inside workings of hospitals and so forth. It has been a difficult few weeks.

But this is not what I want to talk about here: or not directly. Because spending the last few weeks actively involved with questions about the way that medicine works, has got me thinking about the way that philosophical diagnosis often works. I have long thought that philosophy — that strange business of thinking through existence and finding creative practices in response to this thinking-through of existence — is to some extent a diagnostic exercise, one that explores, and makes concrete proposals, about how one might live well, just as medicine is a diagnostic exercise that explores, and makes concrete proposals, about how one might be well. A long time ago now, I found myself intrigued by the notion in Buddhism that the so-called Four Noble Truths are diagnostic in intent, and are directly modelled on a medical model. First you diagnose the symptoms, then you diagnose the cause, then you establish if there is a cure, and then you set out the stages of the cure. This kind of model has, to an extent, become a model for how I think about philosophy more generally.

But there is, I think, a problem with the tendency to see philosophy in the light of this kind of medical analogy. It is a problem that exists in certain presentations of Buddhism, but that also exists in other forms of philosophy that attempt to explore the ills of how we are living, and to suggest how we might put these ills to right.

The problem can be made clearer if one looks more closely at how diagnosis and treatment work in medicine. The fourfold formula above is a pretty good approximation. You start with, “Oh, look, there’s a problem!” Then you look into the possible causes. Then you think about how, knowing the cause, you might treat the problem (sometimes, you don’t need to worry about underlying causes to treat symptoms, but often it can help). Then you prescribe whatever therapeutic course is the best response to the problem. So what is the difference when it comes to philosophy? The difference, I think, is that a good doctor will not assume that there is some kind of fundamental condition of corporeal existence, a fundamental condition for which there is a single cure. A doctor who prescribed antibiotics (or exorcism, or cupping, or a week’s holiday) for everything under the sun—broken legs, viruses or what have you — would be a poor doctor indeed. There is no single fundamental condition that is “illness”; and so there is no panacea for all ills. This is why doctors need a degree of cunning. They need their wits about them, they need to know that bodies are complex and that they behave in all manner of different ways, and they need to know that there are innumerable ways of responding to these complexities. Not only this, but there is not always a problem: a good doctor is also able to diagnose, sometimes, that nothing much is wrong, and that patient can be sent upon their way, reassured that nothing (at least at the moment) needs to be done.

In the light of this, sometimes it seems to me that philosophical diagnosticians lack the cunning of their medical counterparts (not for nothing were the precursors of today’s doctors called “cunning men”). Let us say, for the sake of argument, that if doctors treat bodies and what goes wrong with bodies, philosophical diagnosticians try (at least) to treat lives, and what goes wrong with lives. But it seems to me that good philosophical diagnosticians, just like good doctors, should be capable of recognising that lives too are complex things, and that just as there is no single “human condition” that needs treating, so there is no single treatment that is appropriate. Indeed, a good philosophical diagnostician, I think, should — just like a doctor — have the ability to recognise that sometimes there is nothing much wrong with the way that life is going, and to refrain from offering remedies that in truth remedy nothing (and that may have unwelcome side-effects).

This is why talk of the “human condition” is so unhelpful. It would be unwise to consult a doctor who believed that there was a single illness that pervaded all of humanity and that required a single cure; and I think it would be unwise to consult a philosopher who claimed the same thing. For philosophy to be useful, we need to free ourselves firstly from the idea that there is something inherently and necessarily wrong about our existence, and secondly from the idea that the things that do go wrong within human life can be gathered together into a single problem. Then we can revisit the various philosophies that aim to respond to the different problems with which we might be confronted not as “cures” for some over-arching “human condition” or sickness, but instead as contributions to what might be called the pharmacopoeia of humankind, a store of knowledge, experience, hunches, proposals, suggestions and ideas to which we have access, and which might be used — now here, now there — to address problems as and when they arise. It is this approach that I took in my little book Introducing Happiness—A Practical Guide, published earlier this year: a book that has disappointed some readers in its refusal recognise either a single problem — “unhappiness”, for example — or a single solution, for example, “happiness”.

So let me end on a personal note. The last few weeks have been unusually difficult. Buddhist friends might say that I’ve been encountering what they call “Reality” (spoken in such a way that the capital “R” is almost audible). Certain Norwegian philosophers might like to claim that I’ve been face-to-face with “the human condition”. But what has been going on, it seems to me, has been rather more everyday and pragmatic. These few weeks have been made up of now this, now that particular demand or difficulty; and in responding to these demands and difficulties, no single body of knowledge has provided the resources that have helped us, between ourselves, to respond to each of these problems. Nevertheless, over these few weeks, I’ve been enormously grateful for the little philosophy I have studied over the years, this rich pharmacopoeia that has been bequeathed to us all, whether drawn from the ancient Greeks, the Buddhist traditions, Chinese thought, or more recent philosophy (a body of knowledge to which we have, these days, the most extraordinary access). I have been grateful, because this body of knowledge has helped with navigating the difficulties of these peculiarly difficult few weeks, and because it will, I am sure, help with navigating the difficulties of the weeks to come.

There is no human condition. There is no philosophical cure for the human condition. Recognising these two things, I am reminded, once again, of the very usefulness of the various philosophical traditions as a resource for living.

December 14, 2012

Updates, Interviews and Readings

A few small bits and pieces… First of all, for those of you who have not yet read it, there’s a long interview with me on the blog of the tireless blogger and writer, Morgen (“Morgen with an ‘e’”) Bailey, published last week. The interview is here if you would like to have a read.

Secondly, I’ve updated this site to the shiny new WordPress 3.5 and updated the theme as well. There shouldn’t be any problems or glitches, and things should be functioning a bit more smoothly after the update, but let me know if there are any problems.

And finally, I’ve just put up a post on my events page for a reading I am doing in February of next year at the Cultural eXchanges festival, with poet Alan Baker. We’ll be talking about the Yijing 易經, about poetry, about divination and about storytelling. It should be a fun event, so do come along if you are in Leicester. Full details are here.

December 10, 2012

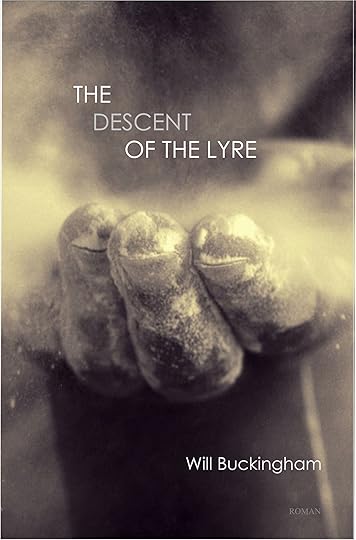

US Launch of The Descent of the Lyre

For those in the USA, my novel, The Descent of the Lyre should be released over the other side of the water tomorrow, on the 11th December. So some time during the next week, news of its availability should have filtered through to your favourite bookseller: just in time for Christmas…

November 29, 2012

Lyre reviewed on Vulpes Libris

I was very pleased this morning to wake up to a lovely review of The Descent of the Lyre on the excellent Vulpes Libris, one of my favourite book blogging sites. Here’s a short extract:

“It’s just a good novel, a very good read, and a highly memorable tale told simply. Buckingham also writes compellingly as a guitarist, the descriptions of the music also sounding like music, in how the words sit on the page and how the phrases are paced… I enjoyed this novel very much for its feeling of being a fable, a handed-down tale, constructed from bits and pieces of fact and fiction, blended back into myth.”

Read the full review here.

November 28, 2012

On Radio Wildfire, in the Loop

Radio Wildfire is one of the UK’s most innovative literary radio stations, broadcasting on the first Monday of every month, and—in between—offering all kinds of literary goodness in their continually streaming Loop.

This month, I’m in the Loop, giving a couple of readings from my novel, The Descent of the Lyre. Tune in to have a listen here. If you miss either reading, you just need to wait for the Loop to loop on round: but there’s plenty of excellent stuff in the mean-time, from Angela France to Mark Goodwin.

Happy listening!

November 16, 2012

Bibliodiversity, Competition and Charismatic Megafauna

Image Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Image Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Tomorrow is the UK launch event for my novel, The Descent of the Lyre; and I’m delighted to be launching it alongside my good friends, Jonathan Taylor, Maria Taylor and Simon Perril, who are all launching books of their own (Jonathan’s Entertaining Strangers, Maria’s Melanchrini and Simon’s Newton’s Splinter — excellent books all!). It is at times like this that I realise how fortunate I am to work with a bunch of fellow writers who are as talented as they are generous; and it will be a delight to be launching the books en masse, and turning the book launch into a collective celebration.

Yesterday, in the lead up to the launch, I was interviewed by the lovely people at DemonFM about my book and about the launch, and they asked me an intriguing question that I’d never been asked before: what about the fierce competition that exists between writers? How do I deal with it? After all, why launch your book alongside your competitors? For a moment, I was not sure what to say; and the reason I was not sure what to say was in part that I think competition is greatly over-rated. The business-world article of faith that competition drives “excellence” is, at best, only a dangerously small part of the story and, at worst, simple nonsense. Competition is often depicted as the primary engine of all that is good in the world, but this is a view that can only be sustained if we imagine that the world is structured in terms of a single hierarchy of excellence. However, when it comes to writing (and to many other things), it is clear that this single hierarchy simply doesn’t exist. Writing is not one, but instead many things. It makes sense to see literature less like a Great Chain of Being (with Shakespeare close to the top and Barbara Cartland somewhere near the bottom), and more like a rich ecological system made up of countless niches. Writing well, I think, is not so much about clambering up some abstract ladder of greatness and influence, as it is about creatively making the most of one or another ecological niche within the great jungle of literary possibility.

It’s easy to get caught up in a kind of spellbound admiration of the charismatic megafauna of the literary world: Don DeLillo, or J.K. Rowling, or Jonathan Safran Foer, or Margaret Atwood. But whilst these behemoths stride through the jungles of the literary world, there are plenty more writers, who to my mind are as interesting if not more interesting, scurrying around in the undergrowth, going about their business, exploring now this, now that, producing books and poems and stories. They are often a bit more reclusive, a bit harder to spot, less easy to catch on camera; but they are also more numerous, and are well worth the patience it takes to track them down. And so, whilst I have nothing against charismatic megafauna, these days I am often as fascinated, if not more, by the mesofauna and microfauna of the literary world, by those people producing beautiful and strange little books in tiny editions, books that most of us will never have heard of, poets crafting lovely, startling lines tucked away in small, beautifully-formed pamphlets, all of this sheer, seething life that makes up the greatest proportion of the bibilodiversity in the jungle of literature. And what you realise when you become aware of this sheer diversity is that most writers, most of the time, exist happily alongside each other. Sometimes they ignore each other. Sometimes they exist in contented symbiosis. Sometimes they stray into each other’s territories and there are little scuffles: but these generally don’t lead to the loss of much other than a bit of fur and dignity. Most of the time, the jungle is peaceable.

As somebody who has been fortunate enough to spend much of my time in this more or less peaceable jungle, sometimes I glance at other writers shambling past, and gaze upon their books, and find that I am filled with admiration. So I read them, and take delight in them, and hope to learn from them. But I also know, ultimately, that I cannot write what they write, and they cannot write what I write, because we inhabit different niches. So I get on writing what I write, because I am not certain that I could have chosen otherwise, because I am aware that I write out of impulses and thoughts over which I have little control, out of commitments that are mine without ever having signed up to them. And it is in this environment of relative freedom from competition, this network of peaceable relationships, friendships and mutual indifferences, that a rich bibliodiversity—and thus a richness of word, thought and image—can be guarded, maintained, and can be encouraged to flourish.

So all of this is why, tomorrow, I am delighted to be launching my book alongside the magnificent work of such good and talented and diverse writer friends. We are four very different writers; our books are four very different books. The sheer difference of the books that we are launching is, for me at least, a cause for celebration. It is a pleasure and an honour to be celebrating this mass launch together. Long live bibliodiversity!

[If you want to come to the launch, the details are here].

Contact Form

Just a quick post to say that I’ve fixed the contact form on this site. Never needing to contact myself, I’d overlooked the fact that after changing a few settings, the form was no longer working properly.

Things should now be back to normal (I’ve just tested the new form, and it works fine), so you can go here to get in touch if you want to say hello.

November 12, 2012

“The Lake” – a Short Story in “Overheard: stories to Read Aloud”

I’m very pleased to say that today is the publication day for Overheard – Stories to Read Aloud, edited by Jonathan Taylor and published by Salt Publications.

My contribution to the collection (in the section called “Laughing Stories”) is called “The Lake”, a story I owe to a strange encounter with a nude bather, several years ago, somewhere in the hills of Bulgaria: but don’t buy this wonderful collection just on my account. It’s full of great stories by the likes of Ian McEwan, Louis de Bernières, Hanif Kureshi, Vanessa Gebbie, Tania Hershman, Kate Pullinger, Salman Rushdie, Blake Morrison, not to mention many of my wonderful fellow writers from here at De Montfort University. What better in the cold, winter months than turning off the TV, unplugging the internet, and spending your evenings with friends, reading out loud?

November 11, 2012

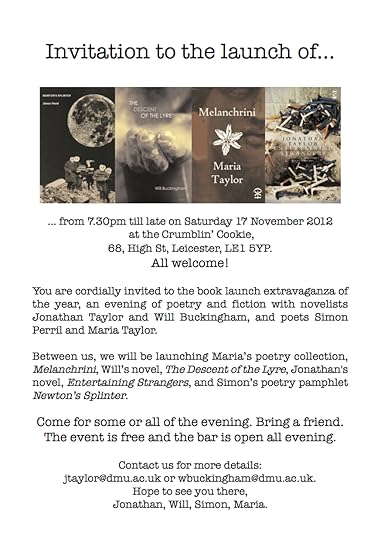

Book Launch!

If I’ve not posted here on The Myriad Things for a while, it is in part because things have got very busy with work and with various other projects, and in part because I’ve been getting ready for the launch of The Descent of the Lyre here in Leicester next week. I’ll be launching the book along with three good friends, all of whom are launching their own publications (Jonathan Taylor’s novel, Entertaining Strangers, Maria Taylor’s poetry collection, Melanchrini and Simon Perril’s poetry pamphlet, Newton’s Splinter) at my favourite Leicester venue, The Cookie Jar. So if you happen to be within striking distance of Leicester on the 17th November, come along to join the party. It’s free, and the bar is open all evening.

Here’s the invite (click for full size).

Meanwhile, the Lyre has been getting some nice reviews here and there, including an excellent five star write-up on theBookBag.co.uk. Do pay them a visit and see what they have to say.

Book Launch! November 17th 2012.

For those of you who are in striking distance of Leicester, in the UK, do come along to the book launch of the year. I’ll be launching The Descent of the Lyre along with Maria Taylor who will be launching her poetry collection,Melanchrini, Jonathan Taylor who will be launching his novel, Entertaining Strangers, and Simon Perril who will be launching his poetry pamphlet, Newton’s Splinter.

It should be a fabulous evening! It’s free, and all are welcome. Here’s the invite (click for full size).

Will Buckingham's Blog

- Will Buckingham's profile

- 181 followers