Will Buckingham's Blog, page 24

May 7, 2013

Document Mountains, Meeting Oceans

Somewhat to my sadness, the teaching year is over; but because bureaucracy abhors a vacuum, rushing in to fill the void left by the departing students is a coming tide of endless meetings, a long summer of juggling paperwork. It’s always a relief when the autumn rolls around, and I head in to my first lecture of the new academic year to see the ranks of faces from the years before, and I have a chance to remind myself that this is why I am doing the job.

They are strange, these summer months in the academic world. Everybody imagines that we are retiring to our quiet hillside villas to write in our libraries, when we are, in fact, lost in a blizzard of spreadsheets and documents and meetings known only by their acronyms. So the following passage struck something of a chord. It comes from the wonderful A Dictionary of Maqiao, which I’m picking my way through in Chinese, with the English translation to one side. The novel, written by Han Shaogong (韩少功) and translated beautifully by Julia Lovell, is a dictionary of the rural village of Maqiao during the Cultural Revolution. It is savage, funny, wonderfully digressive, and deeply strange—my kind of novel. I’m about half way through, as I’m making my way through the Chinese slowly; but the following, from the dictionary entry on “Speech Rights”, particularly struck me.

Documents and meetings are both the key to safeguarding power and the best way of reinforcing speech rights. Mountains of paperwork and oceans of meetings are a fundamental or integral part of, and genuine source of excitement within, the bureaucratic way of life. Even if meetings are river upon river of empty talk, even if they haven’t the slightest real use, most bureaucrats still derive a basic level of enjoyment from them. The reason is very simple: it’s only at these moments that the chairman’s podium and the mats of the listening masses will be placed in position, that hierarchies will be clearly demarcated, giving people a clear consciousness of the existence (or lack thereof) and degree (large or small) of their own speech rights… Only in this kind of an environment do those with power and influence, immersed in the language with which they themselves are familiar, become aware that their power is receiving the warm, moist, nurturing, nourishing, safeguarding protection of language… and this is often far more important than the actual aims of the meeting.

“Mountains of Paperwork and Oceans of Meetings”; or, in Chinese, 文山会海 (wen shan hui hai , literally “document mountains, meeting oceans”) — I love this expression. Of course, meetings are not only empty talk: glimmering somewhere amongst those spreadsheets there are, I have to remind myself, useful and valuable purposes. But nevertheless, earlier today whilst we were mid-meeting, with five of us looking frowningly at one version of a spreadsheet whilst a sixth was talking about an entirely different spreadsheet, I thought of Han Shaogong’s book, and I thought that if I am to get through the coming months of paperwork, I’ll probably need crampons, ropes, and plenty of Kendal Mint Cake, whilst if I am to survive the next barrage of meetings, I should probably make sure that, at the very least, I am wearing a rubber ring around my waist…

May 2, 2013

Wrestling the Goat: Article in Reconstruction 13.1

I’m very pleased to have an article in Reconstruction’s volume 13, issue 1, which is a special issue called “How Did I Write That? Reflections on Singularity in the Creative Process.” It’s another of my Yijing-based pieces, mixing reflection and storytelling. This one I’m particularly fond of, because of the strange overlap between the story, and the process by means of which I arrived at the story. The link is here, if you would like to have a read: Wrestling the Goat. Or click on the goats—they’ll like that.

Do have a read through some of the other excellent articles whilst you are at it!

May 1, 2013

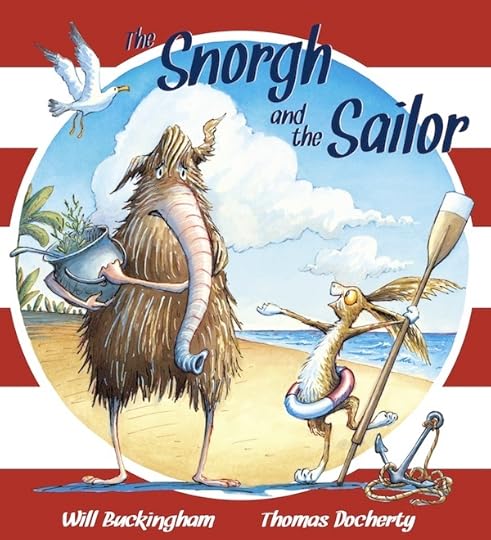

Stockport Schools Book Award

I am delighted to be able to announce that The Snorgh and the Sailor has been shortlisted for the Stockport Schools Book Award. See the link here. It’s up against some strong competition, including Helen Stephens’s lovely How to Hide a Lion, which is also published by Alison Green.

April 25, 2013

A Poem by Han Shan

I’ve been entertaining myself over the last few days translating some poems by Han Shan; and just for the hell of it, I thought I’d post one translation here. I don’t write much poetry of my own (although I used to), so I’m enjoying the experience of taking a break from writing prose, and tinkering with translations.

If you want a bit more background to this fabulous poet, to this particular poem, and to the challenges of translation, you can read Tony Barnstone’s excellent article here. But this poem will probably appeal to Buddhish visitors to this blog.

Self and No-self

There is a self,

there is no self;

this is me,

or then again not me.

This is how

I turn it over in my mind,

dragging out the hours

sat by the cliff.

Between my feet

the green grass sprouts,

above my head

the red dust falls,

and seeing me there,

the common folk

surround my bed

with funeral wine and flowers.

The article linked to above has three alternative translations, as well as the original, so you can have fun comparing, and finding objections to my version. That last line is a bit tricky, incidentally…

April 19, 2013

Radio Leicester

For those in the East Midlands, I’ll be on Radio Leicester tomorrow (Saturday 20th April 2013), on the Ed Stagg show talking about whether—and perhaps how—books can change your life, as well as all kinds of other things. Catch me between 12pm and 2pm for a couple of hours of music and chat with the other guests. According to the blurb, on the show “The best minds in Leicestershire and Rutland unravel life’s little mysteries.” So I’m looking forward to a bit of unravelling.

April 18, 2013

Two Tales of Horse-Training

Lately, I’ve been thinking about training horses. Admittedly, this has been more of an abstract and philosophical concern than a practical one: generally I don’t have much to do with horses, and horses don’t have much to do with me, even though I sometimes go down to the meadows out of town and admire the beasts from afar. So whilst I haven’t been planning to pack in all the writing and the academic stuff and so on, to take up the mantle of a horse trainer, I have been thinking about is the notion of horse-training as a metaphor for training more broadly.

It was a long time ago now that I first came across the Pāli text, the Bhaddāli sutta, and was charmed—or perhaps taken in—by its account of the virtues of horse training. Bhaddāli, according to the text, is a monk who is unwilling to subject himself to the monastic discipline, on account—the text tells us usefully—of being “like a fool, confused and blundering.” The Buddha then turns to him and asks the confused monk if he remembers a parable that he once told him about horse-training; and because Bhaddāli is a blundering fool (the kind of blundering fool for whom I have a natural sympathy), he has forgotten the parable, so the Buddha repeats it. Here’s an extract, in the translation by Bhikkhu Bodhi.

“Bhaddāli, suppose a clever horse-trainer obtains a fine thoroughbred colt. He first makes him get used to wearing the bit. While the colt is being made to get used to wearing the bit, because he is doing something that he has never done before, he displays some contortion, writhing, and vacillation, but through constant repetition and gradual practice, he becomes peaceful in that action.”

Next the horse-trainer puts a harness on the horse, which occasions further contortion, writhing and vacillation. But eventually the horse gets used to this too until it becomes a thing magnificent to behold.

“When the colt has become peaceful in these actions, the horse-trainer further makes him act in keeping in step, in running in a circle, in prancing, in galloping, in charging, in the kingly qualities, in the kingly heritage, in the highest speed, in the highest fleetness, in the highest gentleness. While the colt is being made to get used to doing these things, because he is doing something that he has never done before, he displays some contortion, writhing, and vacillation, but through constant repetition and gradual practice, he becomes peaceful in that action.”

The moral is clear: the Buddha goes on to liken the well-trained horse to the well-trained monk, who is “worthy of gifts, worthy of hospitality, worthy of offerings, worthy of reverential salutation, an unsurpassed field of merit for the world.” If you want to have those kingly qualities, if you want to prance and gallop, then you have to suffer a bit of contortion and writhing and vacillation. Bhaddāli is convinced by this argument, and goes away “satisfied and delighted in the Blessed One’s words.”

In many ways, this rings true. Certainly when I first learned to practice Buddhist meditation, I writhed and vacillated and contorted myself a whole load; but—having said this—over time found that I became “peaceful in that action.” And many of the things I have done in my life that have required a degree of training, or that have involved learning new things, have sometimes felt rather like this, involving a measure of writhing or vacillation or contortion in the process of learning to prance and gallop and charge with the highest fleetness and highest gentleness.

But I also can’t help wondering: are writhing, contortion and vacillation always necessary or desirable? Can one do pretty much the same thing, but without all this writhing about? Or—to go further—is this obsession with kingly heritage and fleetness something that should be resisted, precisely because of the writhing and vacillation that it involves? Let me try a counter-thought, moving from India to China, which I rediscovered the other day as I was rambling through the Zhuangzi. This is the translation by Burton Watson.

Horse’s hooves are made for treading frost and snow, their coats for keeping out wind and cold. To munch grass, drink from the stream, lift up their feet and gallop—this is the true nature of horses. Though they might possess great terraces and fine halls, they would have no use for them. Then along comes Bo Le. “I’m good at handling horses!” he announces, and proceeds to singe them, shave them, pare them, brand them, bind them with martingale and crupper, tie them up in stable and stall. By this time two or three out of ten horses have died. He goes on to starve them, make them go thirsty, race them, prance them, pull them into line, force them to run side by side, in front of them the worry of bit and rein, behind them the terror of whip and crop. By this time over half the horses have died…

This is a startlingly different view of the nature of horse-taming, and one that makes me think it is worth looking at my hitherto more or less uncritical view of the Bhaddāli Sutta afresh. The Zhuangzi doesn’t stop here, but—in the same way as the Sutta—makes the connection between sagely exhortation and horse-training; and yet the way that it goes about this couldn’t be more different.

Then along comes the sage, huffing and puffing after benevolence, reaching on tiptoe for righteousness, and the world for the first time has doubts; mooning and mouthing over his music, snipping and stitching away at his rites, and the world for the first time is divided… When horses live on the plain, they eat grass and drink from the streams. Pleased, they twine their necks together and rub; angry, they turn back to back and kick. This is all horses know how to do. But if you pile poles and yokes on them and line them up in crossbars and shafts, then they will learn to snap the crossbars, break the yoke, rip the carriage top, champ the bit, and chew the reins. Thus horses learn how to commit the worst kinds of mischief. This is the crime of Bo Le.

In the days of He Xu, people stayed home but didn’t know what they were doing, walked around but didn’t know where they were going. Their mouths crammed with food, they were merry; drumming on their bellies, they passed the time. This was as much as they were able to do. Then the sage came along with the crouchings and bendings of rites and music, which were intended to reform the bodies of the world; with the reaching-for-a-dangled-prize of benevolence and righteousness, which was intended to comfort the hearts of the world. Then for the first time people learned to stand on tiptoe and covet knowledge, to fight to the death over profit, and there was no stopping them. This in the end was the fault of the sage.

I love this passage from the Zhuangzi. I love the image of the sage “huffing and puffing after benevolence, reaching on tiptoe for righteousness”, because it is both funny and, I think, insightful. And whilst I recognise some truth in the Buddhist story, at the same time I can’t help thinking that when it is held up to scrutiny in the light of the Daoist story, there is a case to answer here. Indeed, I can’t help reflecting that I, too, have been guilty of “huffing and puffing after benevolence”, and that the results of this huffing and puffing have not always been very pretty.

Looking at these two starkly contrasting stories, I am not sure which to side with, or whether it’s possible to find a third position, some kind of Hegelian synthesis (!) of the two. On the one hand, I find my taste for huffing and puffing after benevolence is less acute than it once was. Not only this, but the Buddhist story omits to say what happens to those colts who are not fine thoroughbreds, those wonky horses with matted manes who find themselves undergoing the discipline and then falling by the wayside.

But then, on the other hand, I wonder if there is a kind of appetite for training that is born not out of a desire to huff and puff after righteousness, or to transform oneself into something that one is not, but that arises instead out of a delight and fascination with the business of finding oneself here amid the ten thousand things of existence. In short, there may be more to life than drumming on one’s belly, cramming one’s mouth with food, and passing the time.

I don’t have any firm conclusion to offer here; but I wonder if, between the two stories, it might be possible to navigate a path in which training and education become matters of delight and fascination rather than the burden of the pole, yoke, crossbar and shaft. I wonder if it might be possible to think about a form of learning that harnesses our proclivities and tendencies, rather than one that attempts to supersede them. I wonder if we are too in love with the habit of difficulty when it comes to learning. And here—because it might seem that the Buddhists are coming off somewhat for the worse in this tale of two conflicting tales—let me finish with another story. Back when I was attending classes on elementary Pāli language, I studied with a monk in Birmingham. A small group of us would meet every week to get our heads around Pāli grammar. We’d practice our conjugation of Pāli verbs out loud, reciting together. And before we started our recitations, the monk in question would give a grin and say, ‘OK, let’s play…’

April 13, 2013

Heading Home

I’ve come to the end of my fortnight of Albigensian Goat Wrestling; and so this morning I was up early to catch the train back to Lille, and then from Lille back to London, and then from London back to Leicester, where I’ll arrive some time late in the evening. And I’m pleased to say that it’s been a success in that I’m returning with a substantially revised manuscript of Goat Music (as well as a couple of bottles of good local Gaillac wine…).

I’m writing this from Toulouse station on my iPad, as my laptop this morning has decided that enough is enough, and has stopped working. It was decidedly thoughtful of it to wait until the book was finished before doing so. I’ve not yet got the hang of writing on the iPad, but it has a demonic auto-correct that turns half of what I write into gibberish, so apologies for the scrappiness of this post.

Of course, “finished” is a relative, rather than an absolute, term. I’m going to be passing the manuscript to a few friends to read, and reading through myself to make a few changes. But all being well, Goat Music should be seeing the light of day next year.

There’s not a great deal else to say. but I thought it worth posting an update if nothing else than for the sake of the lovely little 19th century Russian print of a goat and a bear that adorns this post. As my last book was about bears coming and going over the mountain, at least figuratively, and as this one is about goats, it seemed fitting.

April 11, 2013

Legacy: Mythology and Authenticity in the Humanities!

I’m delighted to say that I’m taking part in the keynote round-table for the De Montfort University Legacy: Mythology and Authenticity in the Humanities conference, which will be held in June of this year. The conference aims to explore the cultural legacies and mythologies at play within humanities research, and I’ll be sharing the panel with DMU Vice-Chancellor, Dominic Shellard, and architect and theorist Sam Causer.

It should be a fun event, and there’s still just about time to respond to the call for papers (deadline 16th April) here.

April 10, 2013

Some Ceremonial Questions

I have a knack of being out of circulation for the deaths of major public figures. When Princess Diana died, I was on a Buddhist retreat in Norfolk, and by the time I returned home, the whole thing was over. And I heard about the death of Margaret Thatcher whilst down here in southwest France, where I’m spending a couple of weeks rewriting my next novel. So I have been a little set apart from all of the debate and discussion and rhetoric. I will, however, be back in the UK in time for the funeral, which we are told will be a Ceremonial, but not a State funeral; and whilst mulling over this, I found myself wondering something really rather simple. What is a Ceremonial funeral, and who decides who gets to have one?

I headed over to the official No. 10 Downing Street website to try and find out an answer to this question; but I confess that this did not help much. The website told me that the decision was ‘in line with the wishes of Lady Thatcher’s family’, and that it was ‘with the Queen’s consent’. The first of these suggests that the family are happy to support a decision made elsewhere, and the second suggests that that the queen is also happy, for reasons of her own, to approve it. But it doesn’t tell us anything about the decision itself. It doesn’t tell us who made this decision, nor on the basis of which criteria it was made.

Next I found the a handy parliamentary guide to State and Ceremonial funerals (download the PDF here), but this is also astonishingly unhelpful. “The process for deciding when a state funeral should be held for a person other than the Sovereign,” it reads, “is relatively unclear, not least since it happens so rarely and at long historical intervals. There is no official process set out in public, but the Sovereign, Prime Minister, and Parliament have been involved in the past.”

That, for what it is worth, is the process for State funeral. For Ceremonial funerals, the document is even more vague, noting that there is no parliamentary process needed to authorise a Ceremonial funeral, going on to read, with a studied vagueness, “It is not clear whether Cabinet is consulted, or whether the official Opposition is consulted before the announcement takes place…”

All of this points to the kind of shadowy decision-making process that has no place in a mature democracy. It risks replacing transparent democratic processes with cults of celebrity that can be used for political manipulation by the vested interests of those who are in power.

Here, then, is a suggestion. What if the decision whether a former Prime Minister had a Ceremonial funeral or not was not an unaccountable political decision made in each individual case, reflecting attitudes (whose attitudes, incidentally?) to the individuals who have held the office? What if, instead, the decision was a general principle decided by parliament, and reflecting attitudes to the office of the Prime Minister itself. In other words, what if, in the interests of a democratic and transparent political process, the question “does this person individually deserve a ceremonial funeral?” could be replaced with the question, “do we give former Prime Minsters Ceremonial funerals in this country?”

In moving from the first question to the second, if the decision was to go ahead with Ceremonial funerals for former Prime Ministers, then it would be on a clear an unambiguous principle. Margaret Thatcher, John Major, Tony Blair, Gordon Brown, David Cameron—all of them could have Ceremonial funerals not because somebody or other thinks that they personally do or don’t deserve it, but because there’s a general consensus that the office of Prime Minister is one that deserves a degree of ceremonial honour. And if the decision was that this is not the kind of thing that we wanted, then the families of those who had died could make their own arrangements as they saw fit.

This would have the virtue of clarity, and it would free us from the disadvantages of the present system which is, at best, non-transparent, and at worst, open to the worst kinds of political manipulation.

Image of St. Paul’s: Wikimedia Commons.

The Evolution of the Concept of De 德 in Early China

For visitors to this blog who are not yet familiar with it, the Sino-Platonic Papers website is a repository of freely-available PDF richness and wonder that should not be overlooked. The purpose of SPP, which is edited by Victor H. Mair of the University of Pennsylvania’s Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations is ”to make available to specialists and the interested public the results of research that, because of its unconventional or controversial nature, might otherwise go unpublished”; and new on SPP is an extended essay called “The Evolution of the Concept of De 德 in Early China” by Scott Barnwell of the admirable Bao Pu blog. Scott’s essay is top of my “to read” pile. I’m particularly interested in the idea of “forgetting” the good that one does, which is something I’ve been thinking about for a while. However, it’s a long paper, so it will be a month or so before I get round to it (must get this manuscript finished first…); but you can get your own copy of the paper here, and I’ll write about it when I have the time and leisure to give it my proper attention.

Will Buckingham's Blog

- Will Buckingham's profile

- 181 followers