David Allen Sibley's Blog, page 9

March 4, 2013

Pairs as an aid to hawk identification

Two Red-tailed Hawks in a single tree. Modified photo by David Sibley.

By the end of February, even in cold and snowy Massachusetts, Red-tailed Hawks are courting and forming pairs in preparation for nesting. It’s common to see the male and female of a pair sitting close to each other in a tree, and this provides a very powerful clue to identification.

Hawks are generally solitary and territorial, and will not tolerate another hawk nearby. The only exception is mated pairs. You won’t see two Rough-legged Hawks, or a Red-tailed and a Red-shouldered Hawk, sharing a tree like this on the wintering grounds. Therefore, whenever you see two hawks sitting this close to each other, it’s safe to assume that they are the same species and that they are nesting nearby, which greatly reduces the number of candidate species.

Habitat also helps, and since Red-tailed Hawk is the only large open-country raptor nesting in Massachusetts it’s easy to identify these two birds as Red-tails based on nothing more than their size and their choice of perches.

February 14, 2013

Sibley eGuide for Kindle Fire HD coming within days

Some of you had noticed that the Sibley eGuide was not in the Kindle store any more. Apparently the new Kindle Fire HD tablet required changes in the app, but those are now completed, the app has been resubmitted to the Kindle store for approval, and it should be available within days.

Thank you for your patience and support.

A video bird quiz

The answer is at the end of the video, and in the text below.

It has been a relatively mild winter in Massachusetts, but the blizzard of Feb 2013 put over two feet of snow on the ground, effectively eliminating most of the grassy and weedy habitat sparrows need. In such conditions the plowed edges of roads become an oasis of open ground and exposed seeds, and sparrows gravitate to those edges. Thus a Le Conte’s Sparrow, a very rare visitor to Massachusetts, was found in Concord on 12 Feb. I suspect it had been at this location, somewhere in the acres of weedy and marshy habitat, since at least December, and was only found because of the snow that forced it into the open.

Given its behavior, it’s no surprise that it wasn’t found sooner. Le Conte’s Sparrow is known for being secretive, just like Grasshopper Sparrow and other species in the genus Ammodramus. They rely on camouflage for protection and usually crouch when alarmed rather than flying. The behavior shown in this video – burrowing under matted grass – is something most sparrows simply never do.

February 5, 2013

Dark heron/egret

Can you identify the two birds in this photo?

Photographed by William Horden in Big Cypress Preserve, FL, Dec 2012. Used by permission. You can see William's more artistic work at his website: http://www.hipikats.com

It should be immediately obvious that this photo shows two species of dark herons, and their overall slender shape and uniform grayish color, with no distinct markings on head or neck, reduces the options to two: Little Blue Heron and Reddish Egret.

It is rare to see these two species side-by-side, so we rarely get to appreciate the much larger size of Reddish Egret. This kind of grassy freshwater pool is normal habitat for Little Blue Heron, but Reddish Egret is almost always found on expansive shallow saltwater lagoons.

It’s also a great opportunity to compare the differences in overall color, as well as details of the color of bill, lores, eye, legs, etc.

This is an immature Reddish Egret, less than a year old, based on its lack of plumes, drab grayish color overall and slightly paler and brownish tips on all of the wing coverts. Compared to an adult Little Blue Heron the immature Reddish Egret’s paler ashy-gray and mottled color is easily distinguishable. An adult Reddish Egret would be even more distinctive in color, with clean gray body and shaggy reddish neck.

February 4, 2013

Updated app for iPhone

The Sibley eGuide to Birds app for iPhone has been updated.

This update adds thumbnail images of every species in the scrolling list and in search results, the option to display common names in French, Spanish, or Latin instead of English, the latest AOU taxonomy including splits of Scripps’s and Guadalupe Murrelet, new audio for Bendire’s Thrasher and Cackling Goose, and some minor corrections.

Similar features for Android and other platforms coming soon.

January 2, 2013

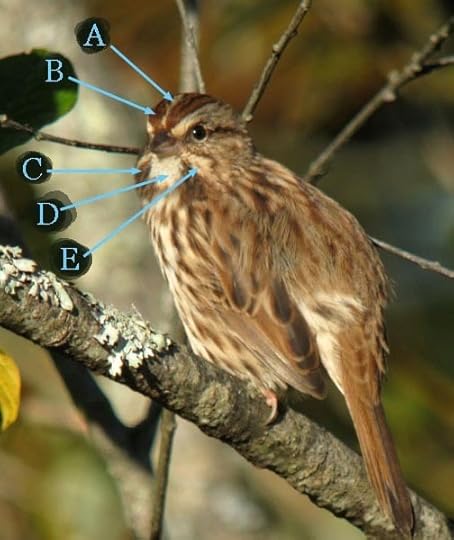

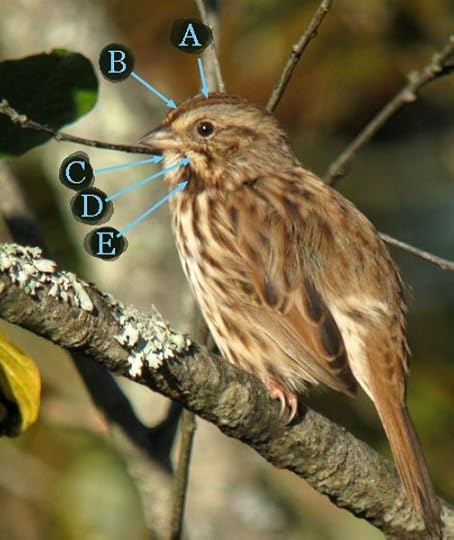

Quiz 54: Head patterns

The three photos below show a Song Sparrow as it turns its head. Your challenge is to locate the plumage marking known as the lateral throat stripe in each photo.

Photos ©David Sibley. Sep 2012, Concord MA.

Head patterns

Please wait while the activity loads. If this activity does not load, try refreshing your browser. Also, this page requires javascript. Please visit using a browser with javascript enabled.

If loading fails, click here to try again

Congratulations - you have completed Head patterns.

You scored %%SCORE%% out of %%TOTAL%%.

Your performance has been rated as %%RATING%%

Your answers are highlighted below.

Question 1

The lateral throat stripe is labeled:

AABBCCDDEEQuestion 2

The lateral throat stripe is labeled:

AABBCCDDEEQuestion 3

The lateral throat stripe is labeled:

AABBCCDDEEOnce you are finished, click the button below. Any items you have not completed will be marked incorrect.

Get Results

There are 3 questions to complete.

You have completed

questions

question

Your score is

Correct

Wrong

Partial-Credit

You have not finished your quiz. If you leave this page, your progress will be lost.

Correct Answer

You Selected

Not Attempted

Final Score on Quiz

Attempted Questions Correct

Attempted Questions Wrong

Questions Not Attempted

Total Questions on Quiz

Question Details

Results

Date

Score

Hint

Time allowed

minutes

seconds

Time used

Answer Choice(s) Selected

Question Text

All doneNeed more practice!Keep trying!Not bad!Good work!Perfect!

December 19, 2012

Posture and shape distinguishes male and female Dark-eyed Juncos

While watching a small flock of juncos at my bird feeder on December 17, 2012, I noticed one particularly brownish female. Considering subspecies and watching it a little further I noticed that it seemed more active and alert, darting around quickly and holding its body more upright than the other juncos. Could this be a regional difference? Maybe some western Juncos have a previously unnoticed tendency to stand more upright? Unlikely, but worth watching more to figure out what was going on.

Pencil sketches of Dark-eyed Juncos showing female (upper) and male (lower). Differences in posture and shape are described in the text below. Original pencil sketch copyright David Sibley.

That one bird really did stand out in posture and behavior among the three or four juncos on the ground, but I realized that the others were all males. Soon another female appeared, and while it wasn’t quite as obvious as the first one, the two females still shared more posture and behavior in common with each other than they did with the males.

Watching and sketching for the next hour or so revealed consistent and fairly obvious differences. I could watch a bird with my naked eye, guess the sex, and then check plumage through the binoculars, and it worked!

A big factor is that males are generally the dominant birds. They tend to sit still and defend one spot as they feed, and will chase away a female that gets too close. The males spend a lot of time in the center of the feeding area and in a “macho” posture, crouching and looking aggressively around, while the females are flitting nervously around at the edges, alert and always ready to fly when challenged.

Besides the females’ more upright posture, more active behavior, and lower rank in the pecking order, I also noticed that they seemed to have thinner necks and a very slight crest.

The more I watched and sketched the more obvious this seemed. The males have a “ruff” of feathers on the back of the neck, smoothing the contour of the crown into the back, and looking particularly broad and “swarthy” from behind. This is enhanced by their crouching posture, but did not seem to be solely caused by that. The neck of the females is more normally proportioned, with a subtle constriction between head and body, appearing narrow when viewed from behind and leaving a sharp corner (a slight crest) on the rear crown.

In summary:

Females tend to stand more upright, with head held high and body higher above the ground

Females have thinner neck, lacking the male’s bulging neck feathers

Females tend to show a very slight crest, while males’ head profile is more rounded

Females are lower on the pecking order and are often chased by males, leading to more active and fidgety movements

This is based on just an hour of observation and about a dozen birds in one situation, but it has worked just as well here on subsequent days. It may not work so well under other circumstances, or in a different flock. There may be situations where some females are higher-ranking socially, and that would negate a lot of the behavioral differences. I will be watching for these differences in the future, and would be interested to hear of anyone else’s experience with it.

Video

I took a few minutes of video, which is very poor quality due to the low light and snowfall, but is still helpful to show the differences described above.

November 16, 2012

Can you find the Cackling Goose?

One of the biggest challenges of identifying a Cackling Goose is just finding one, especially in the east where the species is rare and occurs mostly as single birds (of the relatively large and pale Richardson’s subspecies) among big flocks of Canadas. The photos below show one Richardson’s Cackling Goose among Canadas. See if you can pick it out in each photo, then read below for tips on what to look for.

Canada and Cackling Geese, Acton, MA. 14 November 2012. Photo by David Sibley.

Canada and Cackling Geese, Acton, MA. 14 November 2012. Photo by David Sibley.

Canada and Cackling Geese, Acton, MA. 14 November 2012. Photo by David Sibley.

Canada and Cackling Geese, Acton, MA. 14 November 2012. Photo by David Sibley.

When looking for Cackling Goose among Canadas I find that it’s best to focus on the body size of the birds and just scan for one that looks smaller or less bulky. You’re looking for a bird about two-thirds the size of the standard Canada Goose.

It’s tempting to scan the flock looking for a bird with a small bill, since that is the most reliable distinguishing feature emphasized in all of the field guides, but the differences are hard to see, and bills are often hidden, and therefore this is not a very good way to find a Cackling Goose. Unless you’re very close to the geese it’s better to ignore bill size until you’ve located a good candidate based on other features.

Once you’ve found a bird that looks smaller, check the overall color. A typical Richardson’s Cackling Goose is slightly darker and warmer brown on the breast, and slightly more grayish or silvery on the back. If you scan through any big flock of Canadas you can find birds that match each of these features, and plumage color by itself is almost useless for picking out a Cackling Goose, but any bird with smaller size and these plumage colors is likely to be a Cackling. None of that is absolutely diagnostic for Cackling, but it will tell you that you’re on the right track and then you can work on studying the bill.

On some individuals (like the one shown above) the warm brown color of the breast blends to darker and more rusty at the upper edge just below the black neck, and this darker breast color helps to set off a small white collar (also only on some individuals). A similar white collar is only rarely shown by Canada Goose.

If you’ve actually found a small goose that looks slightly more golden on the breast and grayer on the back, then it’s time to confirm the identification by studying bill size.

Pitfalls

Judging size is harder than it sounds, since the geese are usually moving around, and standing at varying angles on uneven ground. A bird facing away and standing in a furrow will always look smaller than a bird in profile standing on a ridge. In addition, males average larger than females, and size is quite variable overall. You will have to watch a goose move around for at least a few seconds while comparing it directly to other geese to be sure you’re getting an accurate impression of size, and you can expect a lot of “false alarms” of birds that look small at first and then transform into more normal size. If it still looks small from several angles then it is worth closer study.

It’s a little easier to judge the size of birds that are swimming, since they are all on the same level. The best opportunity to judge size is when something alarms the geese and they are all in alert posture. Scan quickly then for smaller birds.

When comparing sizes within a flock, keep in mind that geese (unlike most birds) often stay together as family groups through the fall and winter. If you find a bird that really looks small, but a few of the geese around it look about the same size, it is worth making some extra comparisons to see if that whole group is smaller than the average of the flock.

I haven’t mentioned neck length above because I don’t think it’s very useful as a distinguishing feature. The neck length of an individual bird can change dramatically depending on stance and alertness. It is true that Cackling Geese average shorter-necked than Canada, but there is just too much variation, and too much overlap, to recommend this as a field mark.

When there is less variation in neck posture – in flight, in alert posture, or when grazing with head down – neck length is more reliable and worth studying, but in most situations it’s just too variable.

Answers

In the first photo the Cackling Goose is the bird in the left foreground with head down; in photo 2 right foreground; in photo 3 second from right foreground with head up; in photo 4 right foreground. All of the other geese are Canadas.

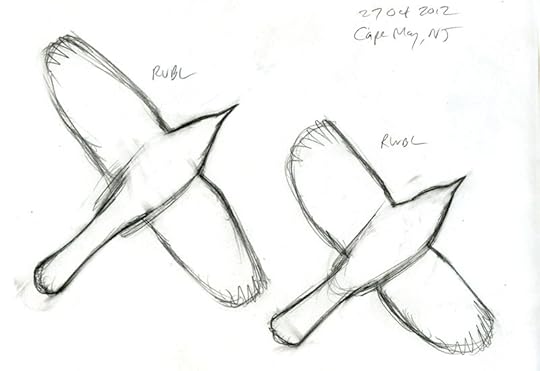

November 5, 2012

My trick to finding Rusty Blackbirds

Almost every Rusty Blackbird that I see in the eastern United States is in flight, so the simple trick is to look up. In order to do that you need to know what to look for: I use sound to know when to look, then look for flying blackbirds that are solitary or in small groups, with long wings and long, club-shaped tails.

Rusty Blackbird (left) and Red-winged Blackbird, showing subtle differences in shape. Original pencil sketch by David Sibley.

Use your ears

First, listen for a slightly different call. All of the blackbirds and grackles give a low harsh check or tuk call in flight. In Red-winged Blackbird this is a relatively simple and unmusical chek, like hitting two twigs together. Rusty Blackbird’s call is more like chook, it has more complexity and depth. Rusty’s call is slightly longer, slightly descending, and with a bit of musical tone. It reminds me vaguely of the harsh chig call of Red-bellied Woodpecker.

These differences are subtle and not easy to pick out, and there is a lot of variation in the calls of Red-winged Blackbirds. Distinguishing Rusty Blackbird by call is definitely an advanced skill, but by paying attention to the various check sounds of blackbirds you can learn to hear the differences. When I hear a Rusty-like call I still like to see the bird to confirm that it also looks like a Rusty, but call is how I know when to look up and the best way to find a potential Rusty, and with a little bit of practice you should be able to use sound in that way.

The song is much more distinctive, and is often given by flying birds even in the fall and winter. It is a short jumble of creaking or gurgling, ending with a high thin whistle – inconspicuous but very distinctive.

Recordings at Xeno-Canto are here: http://www.xeno-canto.org/species/Euphagus-carolinus

Blackbirds do not all flock together

Rusty Blackbirds do not mingle freely with Red-wingeds, even in flight. They are usually seen flying in singles and small groups, sometimes joining larger flocks of other species but usually just along the edges and soon separating. When you hear a Rusty-like call, sifting through a dense flock of Red-wingeds is not worth the time. Instead, look around the edges of a flock or look for a few blackbirds on their own.

Shape is the key

Color is usually no help in identifying flying blackbirds. Most are simply dark silhouettes against a bright sky. Even when lighting is good and colors can be seen the differences are simply too subtle. Distance can blur the streaked pattern on a female Red-winged, or lighting can enhance the rich rufous tones, making it appear very much like a Rusty Blackbird.

The red coverts on a male Red-winged Blackbird are distinctive, and are never duplicated by Rusty. Similarly, if you are close enough and the lighting is good you can see the pale eye of a Rusty (just make sure you’re not looking at a grackle). But other than that there is no reason to look at color, you should focus on shape and proportions.

Compared to Red-winged Blackbird look for:

longer tail with club-shaped tip

longer and relatively narrow wings

shorter head and thin bill

The overall impression is of a more elongated, sleeker bird, with long tail, long wings, pointed head and streamlined body. The wingbeats seem a little slower and flight more buoyant. If you want to focus on one thing then tail shape is probably the single best feature to study, but tail shape alone is not enough to identify this species. If you can combine call and shape, then you should be able to make a very confident (even if subjective) identification. If you can hear the song or see the pale eye, then you’re all set and you can make a more objective identification of Rusty Blackbird in flight.

September 17, 2012

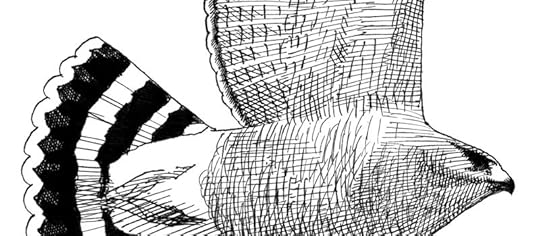

My Pen-and-ink technique

With the publication of the revised edition of Hawks in Flight, I wanted to post a little bit about my drawing technique with pen and ink.

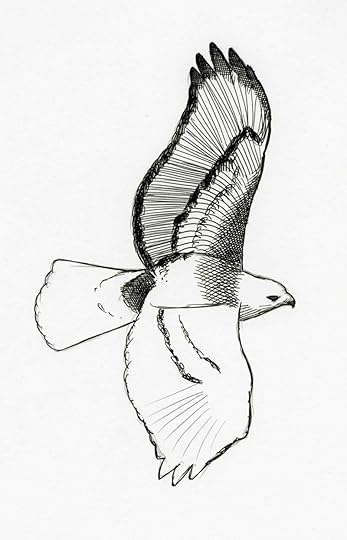

Gray Hawk, drawn for the revised edition of Hawks in Flight. The pale color of this species requires a lighter touch, with sparse fine lines, and in pen-and-ink there is little room for error. If you put on too much ink there is no way to take it back.

African Elephant, my first paid job as an artist, drawn for a travel brochure in about 1978.

I’ve always enjoyed black-and-white drawing. I remember being in third grade and spending hours looking at Earl Poole’s ink drawings in James Bond’s “Birds of the West Indies”. A few years later I was enthralled by the simplicity and grace of George Sutton’s drawings in “Fundamentals of Ornithology”.

Ink was my favorite “formal” medium from my childhood through my late-20s when I started doing a lot more painting. My first paid job as an artist was doing drawings for travel brochures, like the elephant shown above (drawn from photographs when I was about 17) and all of my early published art was pen-and-ink drawings.

I was drawing with a pencil almost every day in the field, and cross-hatching was a major part of my pencil shading technique, so the transition from pencil to ink was very easy for me. By the time I started the drawings for Hawks in Flight (when I was about 24) I had a well-developed style.

The materials I use now are the same ones I used in the 1970s: a bottle of India Ink, a crow-quill pen nib in a handle, and a watercolor brush for painting ink in large areas, and I work on smooth white paper.

I only use one pen size, either 0 or 00, making very fine lines. I can vary the thickness of the lines slightly by putting more pressure on the pen, and I use the brush when I want to fill in large areas of black, but otherwise I just build up darker colors by adding more cross-hatching.

Every drawing begins with a very simple pencil outline. The first lines with a pen simply trace the outlines, then I start adding “structural” lines that will define the contours of the bird – feather shafts are a major defining feature of the contours. Next I’ll work on some of the darkest areas, adding ink with a brush or adding multiple layers of cross-hatching to build up a darker color.

In a color painting I generally work across the entire painting at once, adding a layer to all parts of the bird. But in pen-and-ink I find that it’s easier to add layers in one small area and complete one section, like a wing, then move on and start another section.

In the final stage I sit back to look for rough edges or distracting dots of white in areas that are supposed to be dark, and once those are filled in (try to resist the temptation to keep adding more ink) it is finished.

Below are some close-ups of drawings from Hawks in Flight, where you can get a better sense of the actual process.

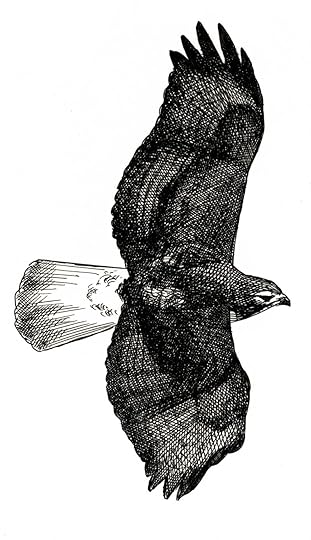

Just starting a drawing of Harlan's Red-tailed Hawk for Hawks in Flight, beginning with a simple pencil outline and adding ink lines to form the "framework". It's very important for all of the lines to follow the contours of the feathers, and I use this stage to set up the form of the bird.

A finished drawing of Harlan's Hawk (similar but not the same drawing shown above). Once the form is created in the early stages, it is simply a matter of adding cross-hatching to create darker areas and shading.

Detail of the body of the immature Common Black-Hawk, showing the combination of brushed areas (thick black streaks) and cross-hatching with the pen to develop shading.

David Allen Sibley's Blog

- David Allen Sibley's profile

- 151 followers