David Allen Sibley's Blog, page 22

October 26, 2011

Does technology make birders lazy?

In a recent post at the ABA blog, a new smartphone app is described that promises to help identify bird songs in the field. Bird song identification software has been around for a long time, mostly running on desktop computers and used for research, and the idea of having that capability in a smart phone has been a very popular future dream of many. This app would send your recording of a bird to a server (where the heavy analysis would happen) and then return the answer to your phone.

An app like this could begin to put bird song identification within reach of novices, and that's exciting. As the developer Mark Berres said "You'll learn more about the world around you, and there's nothing but good in that".

So I was surprised to read the comments on the ABA blog and find that five of the first nine are negative. Commenters are concerned that people would be interacting more with their phones than with nature, that birders won't even have to listen to birds, won't bother to learn the songs, etc. The common thread is that this will create a new generation of lazy birders.

The same principle has been debated for years regarding the use of calculators in schools. A good overview of that debate is here. It's worth noting that there is no evidence that calculator use does any harm to math learning. Some of the arguments in favor of calculator use can be applied directly to this bird song app debate. For example: Calculators allow students to spend less time on tedious calculations, so those who would normally be turned off by frustration or boredom can still learn the overarching concepts of math.

If an app can help relieve some of the initial frustration that beginners experience when they try to identify a sound in the forest, that might be the difference between a good experience and a bad one. Someone who feels like they succeeded in identifying a bird will be more likely to try to identify more.

Sometime in the distant future there might be a device that will simply identify sounds as we walk, and one that we can trust enough that we simply accept its identifications. I think the fear is that birding will become just a transect through the habitat while looking at the smartphone screen and reviewing the collected data. If that happens I may change my mind about this topic, but really, I don't think technology can ever take away the central birding experience of exploring and discovering.

For now, these early apps are going to be a bit cumbersome – you record the sound, send it to the server, wait for a response, read the list of likely answers, listen to the included reference recordings, reject all the suggestions, try to get a better recording to resend, repeat. Anyone who goes to all that trouble is actually going to learn a lot about bird songs, and will quickly graduate to leaving the phone in their pocket and identifying birds much more quickly and happily by ear. That's not lazy. I think that sounds like a great way to learn.

October 25, 2011

On identifying Chipping and Clay-colored Sparrows

I recently commented on this ID problem on MassBird, pointing out differences in details around the eyes.

Chipping sparrow has very distinct, narrow whitish arcs below and ABOVE the eye, contrasting with darker gray-brown feathers, and broken at front and BACK by the dark eyeline. Simply looking for these distinct white arcs is a good quick ID clue, not shared by any other sparrow. (But don't go running to your Sibley Guide to look it up, I didn't appreciate how useful it was until recently, so it's not illustrated very well in the current edition)

On Clay-colored there are pale feathers all the way around the eye, and these blend into just slightly darker feathers, not contrasting at all above the eye (just a broad pale eyebrow stripe). And there is only a very weak dark eyeline breaking the eyering behind the eye.

This leads to the 'open-faced' impression on Clay-colored, since the eye is set in a broad pale area.

After reading my comments, Phil Brown put together a nice comparison of two photos, which you can see on his blog here: http://birdsofessex.blogspot.com/2011/10/sparrow-identification-chipping-clay.html

September 20, 2011

The basics of iridescence in hummingbirds

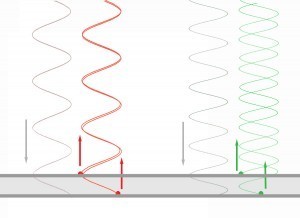

After all the discussion of orange-throated and red-throated hummingbirds, I thought it would be helpful to add a brief and simplified summary of how the brilliant iridescent colors of hummingbirds are produced. These are structural colors, not pigment, which means they are reflected by microscopic structural features of the feather surface.

The gray bands at the bottom represent a cross-section of an air bubble in hummingbird feathers. Incoming light waves are shown in gray. Some light reflects from the upper surface of the air bubble, and some light passes through and reflects off of the inner surface as well. When wavelengths of light (red in this example) match the thickness of the air bubbles. the two reflected waves combine constructively so that light of that color is

The diagram here shows how this happens. The surface of the feather is composed of layers of tiny air bubbles. When light strikes the surface of the feather, some light is reflected from the outer surface, and some light travels through the air bubble and reflects off the inner surface. Light (red in this example at right) with wavelengths that match the thickness of the air bubble are "amplified" as the reflected waves from the inner surface match up and combine with the reflected waves from the outer surface. Other wavelengths (such as the shorter green waves shown in this example) are "out of sync" when they combine after reflecting off both surfaces, and they cancel out. This is the fundamental process that creates the very pure and brilliant colors we see on hummingbirds.

This is an idealized example. In reality the structures that produce iridescent colors in hummingbirds are much more complex, with multiple layers of air bubbles. The refractive index of the material the light must pass through, along with many other factors, can alter the color that is produced, but it is the combined reflections from inner and outer surfaces of the air bubbles that creates iridescent colors. The entire system must be incredibly precise and uniform. The difference between red and orange could be a difference of a few nanometers, and one of the most amazing things about this is that there is so little observed variation in hummingbird colors.

When Ruby-throated Hummingbirds develop orange throats, that means a tiny shift to reflecting slightly shorter wavelengths of light. This could be the result of a thinner layer of air in each bubble, or a thinner layer of solid material forming the outer surface, or a slightly lower refractive index of that material, or many other possible variables.

Still lots of questions…

August 16, 2011

Progress on the orange-throated hummingbird mystery

Thanks to Sheri Williamson (author of the Peterson Field Guide to Hummingbirds) and her recent post titled Orange-throated hummingbirds – not so mysterious after all, we have a solid contribution towards understanding the orange throats of some Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, although I contend that mysteries still remain.

There is still no full explanation for the color difference shown by these summer and winter hummingbirds. Adult male Ruby-throated Hummingbirds - three in breeding plumage (left) collected in April in Florida, and three in nonbreeding plumage (right) collected in Oct-Nov in Mexico. Specimen use granted by Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University ©President and Fellows of Harvard College.

She explains the details of iridescent color on hummingbirds, and a plausible mechanism for color shifts with wear. She also includes two photos that seem to show pretty conclusively a color shift on worn feathers. Given this I stand corrected and I retract the suggestion in my previous post that color shifts with wear are unlikely. Apparently they do occur, and I am glad that Sheri has taken the time to explain it.

That still doesn't solve all of the mysteries, although it does point to some interesting possibilities for answers.

Since wear is part of the equation, it's likely that all Ruby-throated Hummingbirds become slightly more orange-throated over the course of the summer (and there must be some individual variation in the amount of orange shift). And since throat color is mainly being judged subjectively by birders and banders comparing one bird to any adjacent birds, a slight orange shift in all birds would not be noticed, and the throat would have to get really orange before it stands out from its peers.

Wear alone could explain the very drab orange throat color shown by all of the winter specimens at MCZ (see my first post on this subject), but only if there is no late summer molt. In other words, if throat feathers were molted only once in late winter they would be fresh in spring, becoming slightly more orange by late summer and very orange by midwinter. But the late summer molt is well-documented by Dittmann and Cardiff and is confirmed by hummingbird banders.

Donna Dittmann, Cathie Hutcheson, and Scott Weidensaul have all told me that they see no difference in throat color in late summer between the old feathers being dropped and the new feathers coming in. Although Sheri Williamson has posted a photo showing a Ruby-throated Hummingbird acquiring new feathers that are more red than the old ones. I wonder which is the norm? Do the incoming feathers usually look a little more red than the old ones, or do they look the same color?

If new feathers look the same color that would imply that the new feathers being acquired in the late summer are not as red as the feathers that were acquired in late winter. In that case the continued effects of wear during winter could lead to even drabber orange feathers by mid-winter. If the feathers acquired in late summer were also somehow weaker and more susceptible to wear that would lead to even more wear and even drabber feathers.

Interestingly, this hypothesis actually comes back around to my original idea, that the orange-throated specimens at MCZ are in a drab, "nonbreeding" plumage, one that becomes drabber and more obvious as the winter progresses. Contrary to my original post (and as corrected in my second post) the orange-throated males seen in late summer are not the same as the orange-throated winter specimens. Birds in worn summer plumage sometimes become obviously orange, and based on the MCZ specimens birds in worn winter plumage are always orange.

August 15, 2011

The finer points of wing translucence

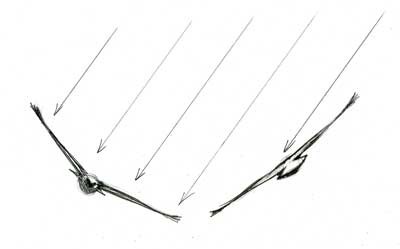

Imagine that the sun is above and to the right of these soaring juvenile Red-tailed Hawks. The birds have the plane of the back nearly perpendicular to the sun (upper) or nearly parallel to the sun (lower). Original gouache painting copyright David Sibley.

Patterns of translucence in wing feathers provide useful identification clues for many species of birds – terns, gulls, hawks, and others. Generally the translucent parts of the wing are those where there are fewer layers of feathers to block the light, and less pigment in the feathers. I've written about this before in my book Birding Basics and elsewhere, but I have just noticed another source of variation that I had not considered before.

I was enjoying a bright sunny morning a few days ago, watching two juvenile Red-tailed Hawks playing with each other in the air above me, and as they turned in flight it became apparent that their wings were strongly translucent at certain times and nearly opaque at others. A little careful observation revealed that the brightest translucence showed when the plane of the bird's back was nearly perpendicular to the sunlight, and least when the plane of the bird's back was closer to parallel with the sun's rays.

It makes sense, but I had never thought of it before. As a soaring hawk turns in circles it will alternate between having the sunlight striking its back more or less perpendicularly, and then at the other side of its circle having the sun striking its wings more "end-on" at only a low glancing angle off the upper surface of the wings. It is in this latter position that little or no light comes through the wings.

Diagram showing how the turns of a soaring hawk can dramatically alter the angle at which the sun strikes the upper surface of the wings. Original pencil sketch copyright David Sibley.

It's a small point, but something to keep in mind when watching a flying bird or comparing one bird to another.

August 14, 2011

Orange-throated Hummingbirds: more questions

Now updated by a new post Progress on the Orange-throated hummingbird mystery. This adds to my previous post about orange-throated hummingbirds.

After hearing from a couple of hummingbird banders affirming that they do not see a change in throat color in the fall as male Ruby-throated Hummingbirds go though their summer molt (and the fact that banders have been aware of this molt for many years) I will have to modify my previous post suggesting that the birds molt into an orange-throated nonbreeding plumage. It was a very neat and simple hypothesis, explaining all of the data that I had, but it looks like it's a "just-so story".

In addition, it appears that there may not be a connection between the occasional orange-throated males seen in late summer (before molt, according to the hummingbird banders) and the orange-throated winter specimens at MCZ (after molt).

An orange-throated male Ruby-throated Hummingbird. Photographed in CT, 11 July 2011, copyright Mark Szantyr.

In July 2011, Mark Szantyr photographed this male Ruby-throated Hummingbird with an orange throat in Connecticut, and has allowed me to post a couple of his photos of that bird here as part of this discussion. You can see the rest of the photos and more at Mark's website.

An orange-throated male Ruby-throated Hummingbird. Photographed in CT, 11 July 2011, copyright Mark Szantyr.

The date of this orange-throated bird – 11 July – is too early for it to have completed molt. Dittmann and Cardiff found the peak of molt in mid-July through August, with throat feathers molted throughout the period but the throat generally in the later stages of molt for any individual bird. This individual also doesn't show the drab fringes on the gorget feathers that are apparent on the MCZ specimens, instead it seems to have a brilliant and uniform orange gorget.

This shift to orange color is presumably the result of a slight alteration in the structure of the gorget feathers, so that they reflect very slightly shorter wavelengths of light. I still doubt that it has anything to do with wear, for two main reasons: 1) if this was caused by wear I would expect to see a lot more such birds in late summer, but they are extremely rare. 2) If this was caused by wear I would expect the throat to be less uniform in color, as wear would not affect all the feathers precisely the same way. (Update 16 August – apparently an orange shift can be the result of wear, see my later post)

The brilliant iridescent throat color is produced by tiny air bubbles that are prefectly calibrated in thickness to reflect a certain wavelength of light. A shift to more orange color would require a slight thinning (or collapse) of the air bubbles on the order of nanometers… maybe that could happen as the feathers age, but again I would expect that effect to be more uneven (with some feathers still reflecting red) and more common.

My suspicion is that this bird molted into these feathers in the spring, and has been the same color since then. In that case orange-throated hummingbirds should show up during spring migration. All of the reports I have heard have come from late summer and fall, but maybe that's just the season when most Ruby-throated Hummingbirds are seen and studied. Have orange-throated birds like this ever been seen in spring? (Update 16 August – orange shift can be caused by wear, see my later post, but it's also possible that some birds begin the summer with more orange feathers, so still worth watching for orange-throated males in spring).

The drabber and more orange-toned throat color of the MCZ specimens remains a mystery. I'll continue to check museum collections as I am able, and I'd be very grateful for any info from others. It would also be helpful to know if observers who see this species on the wintering grounds in Mexico and Central America see this variation in throat color in real life.

Thanks to Mark Szantyr for the photos, and to Cathie Hutcheson and Scott Weidensaul for comments.

August 10, 2011

New Art for Sale – August

Pileated Woodpecker. Original gouache painting copyright David Sibley.

I've just updated the New Art page, adding a few paintings that I've completed in the past month, including the Pileated Woodpecker shown here. Thanks for taking a look.

August 5, 2011

Abnormal coloration in birds: Melanin reduction

A full (or true, or complete) albino Northern Cardinal, recognizable by the lack of pigment in the eyes, making them appear pink. see below for discussion. Original gouache painting copyright David Sibley.

The presence of white feathers on a normally dark bird is the most frequently seen color abnormality. Every birder can expect to encounter white or partly-white birds with some regularity, and the more striking examples will stand out even to novices.

All black and brown coloration in birds comes from melanin (of two types). Birds create melanin pigments using an enzyme, and this melanin is deposited in the growing feathers by color cells. At any stage and for many different reasons this complex process can break down, leading to a variety of conditions:

an inability to produce melanin and complete absence of melanin throughout

an inability to deposit melanin in the feathers and an absence of melanin in some or all feathers

a lack of one type of melanin (many possible causes), leading to an absence of that type while retaining the other

a failure to fully oxidize the melanin leading to a change in color from blackish to brownish

a partial loss of one or both types of melanin (many possible causes), and therefore a lower concentration of melanin in the feathers

Through careful study birders can sometimes deduce the cause of the abnormality, but different conditions can produce nearly identical results. Conversely, the same condition in different species of birds can produce very different results.

Terminology

There has been some recent discussion about the proper terminology for these conditions (Buckley 1982, Davis 2007, van Grouw 2006), with competing proposals from aviculturists, ornithologists, and birders. One of the reasons for the disarray is the lack of a simple "umbrella" term for all conditions involving the reduction of melanin. Birders cannot be expected to analyze each odd bird and choose the proper term to apply to that particular form of melanin reduction, and this leads to misuse of technical terms. I propose that the term "albino" is already in popular use and has become the default name for the category. Birders should continue to use the terms "albino" and "partial albino" to refer to any bird with abnormally white or pale feathers. When you look at a swirling flock of blackbirds and see one with a white tail, or one that is pale tan all over, it is OK to say "partial albino, flying left!"

A true albino is a very specific genetic mutation, rarely seen in the wild, and can easily be referred to by calling it a "full", "true" or "complete" albino. The other terms mentioned below (leucistic, dilute, etc.), and others, can be used for specific cases, but consider all of the possibilities and be wary of false precision.

The term leucistic has a confused history. In the introductions of the Sibley Guides I said the term leucistic is synonymous with dilute plumage. That usage was fairly common among birders at the time, and I was unaware that it contradicted several scholarly publications (e.g. Buckley 1982, van Grouw 2006) which define leucistic as the total lack of melanin from some or all feathers (what I called partial albino in the guides). It does make sense to distinguish birds that are unable to deposit melanin (my partial albino, their leucistic) from birds that are able to deposit melanin but only in low concentrations (my leucistic, their dilute). Below I've used the term leucistic (not partial albino) for birds which cannot deposit melanin, which helps to distinguish these birds from the narrowly-defined true albino, and allows use of the term "partial albino" as a general category for any bird showing any form of reduced melanin. These terms should be corrected in the introduction of the Sibley Guides.

The True Albino

A full or true albino (see illustration at the top of this page) is a very specific mutation with a well known genetic cause similar across all vertebrates. These birds are unable to produce melanin at all because of the absence of the required enzyme tyrosinase. All of the plumage is white and the skin is unpigmented. Even the eye is unpigmented, and appears pink or red as we see the blood vessels in the retina. Melanin serves some critical functions in vision and in protecting the eye from UV radiation, so full albino birds can't see well and for that and other reasons don't survive long in the wild. Adult full albino birds are essentially never seen in the wild. Note that the inability to produce melanin does not affect the red carotenoid pigments, so the red color appears more or less as usual on this bird's feathers and bill. An albino bird is not necessarily all white!

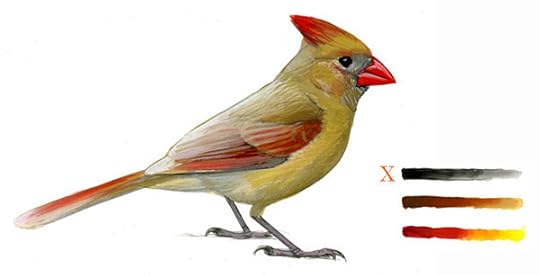

The normal Cardinal

A female Northern Cardinal with entirely normal colors. The plumage color is a combination of black/gray eumelanin, chestnut/buff phaeomelanin, and red carotenoid pigments. Original gouache painting copyright David Sibley.

Fully leucistic

A fully leucistic Cardinal lacking all melanin in all feathers. Original gouache painting copyright David Sibley.

These birds can produce melanin, so the eye appears black, but something prevents them from depositing melanin in the growing feathers. The red carotenoid pigment is unaffected so the feathers are red in all the normal places for a female cardinal. Note that in any of the numerous species that lack carotenoid pigments (e.g. Song Sparrow, Herring Gull, Blue Jay, American Robin, etc) exactly the same underlying condition – a total lack of melanin in the feathers – would result in completely white plumage.

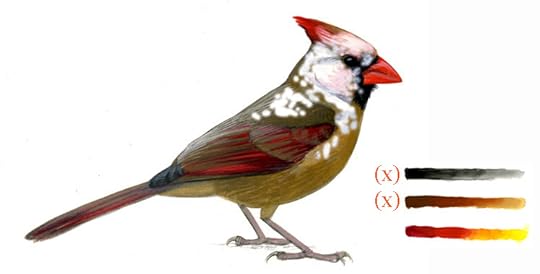

Partially leucistic

A partially leucistic Cardinal lacking melanin completely in some feathers, while other feathers are normal. Original gouache painting copyright David Sibley.

This is probably the most commonly seen plumage abnormality in wild birds. This mutation is extremely variable in appearance, as birds can have just a few white feathers scattered on any part of the body, or whole sections of the body white, or the entire body white (fully leucistic, above). The white feathers are often grouped in feather tracts, so that most of the head is white (as shown here), or some of the wing coverts are white, or most of the tail, etc.

Lacking eumelanin (Non-eumelanic)

A female Cardinal completely lacking the black/gray pigment eumelanin, this leaves only the rufous to buff phaeomelanin pigment (and red carotenoids). Original gouache painting copyright David Sibley.

The most obvious differences from the normal bird include the lack of the blackish face and the greatly reduced pigment in wings and tail leading to very pale wingtips and tail tip. This condition is rare, and can be very similar to some dilute plumage conditions. Note that in a species that lacks the chestnut/buff phaeomelanin pigment (crows, many gulls, etc) this same condition – a lack of eumelanin – will result in completely white plumage.

Lacking phaeomelanin (Non-phaeomelanic)

A female Northern Cardinal completely lacking the chestnut/buff-colored pigment phaeomelanin. Original gouache painting copyright David Sibley.

It retains the normal dark gray eumelanin in the wing and tail color, and the dark face, but the body feathers appear quite abnormal. They lack all of the warm buff tones of phaeomelanin, leaving only pale and plain neutral gray. This condition is rare. There is no bird known that has only phaeomelanin pigment, it is always found with eumelanin, so this condition will never result in an all white bird.

Dilute plumage

A female Cardinal showing dilution. Original gouache painting copyright David Sibley.

Melanin of one or both types is produced and deposited in the feathers, but at low concentrations. The resulting pale gray-brown pigment is very susceptible to fading, and these individuals quickly become bleached by the sun. In dilute birds the relative concentrations of melanin on different feathers often remain the same as on normal birds, but all are much paler so the bird shows a faint "ghost" of the normal pattern. This is particularly striking on strongly-patterned species such as raptors or immature gulls, where the dilute bird will show the typical pattern (e.g. tail bands, etc.) but all in a faint pale brown. Many dilute birds have about 50% of the normal concentration of melanin. The palest dilute individuals can be nearly indistinguishable from fully leucistic birds, especially when bleached and worn.

Not illustrated here:

a mutation that leads to incomplete oxidation of the blackish eumelanin, so it is deposited in the feathers as a slightly paler brown color and is very quick to fade. This is obvious when it occurs in species like crows, but far less obvious on a Cardinal.

a condition known as grizzle, in which feathers are not uniform but have varying concentrations of melanin, partially dark and partially pale.1

an inherited condition known as acromelanism, in which feathers grown on warmer parts of the body (e.g. the chest and belly) are less pigmented than feathers grown on colder parts (e.g the top of the head).

And there are other variations, with other causes, too numerous to be mentioned in a brief overview such as this.

Conclusion

The coloration of birds is simple in some ways, and marvelously complex in other ways. Birds with abnormal plumage can be strikingly beautiful or just unusual-looking, and they can provide a fascinating deductive challenge as we try to figure out just what is going on.

References

Buckley, P. A. 1982. Chapter 4: Avian Genetics. in Petrak, Margaret L. (Ed) 1982. Diseases of Cage and Aviary Birds, 2nd edition. Lea & Febiger, ISBN 8121-0187-1

Davis, J. N. 2007. Color abnormalities in birds: A proposed nomenclature for birders. Birding 39:36–46.

van Grouw, H. 2006. Not every white bird is an albino: sense and nonsense about colour aberrations in birds. Dutch Birding 28: 79-89.

Notes

Note that grizzle is not to be confused with the pale-based flight feathers seen in some juvenile crows and other species. That is apparently a temporary condition caused by environmental issues (presumably health and diet). It is not a mutation and the same bird will grow normally-pigmented feathers in its next molt.

August 4, 2011

The mystery of the orange-throated hummingbirds

An orange-throated male Ruby-throated Hummingbird seen in late August 2009 in Virginia. Photograph copyright Masaharu Ishii, used by permission.

Update 16 August: a new post Progress on the orange-throated hummingbird mystery.

Update 14 Aug 2011: A follow-up to this post is now available, tempering some of these points and adding more questions – Orange-throated Hummingbirds: more questions.

Every year in August and September, a few perplexed observers in eastern North America send out questions about an odd hummingbird they have seen. The description is always the same: "similar to the common male Ruby-throated Hummingbird, but with an orange throat."

The species involved – Ruby-throated Hummingbird – is quickly and easily confirmed, and if these birds generate any further discussion, it is simply to suggest that they are odd males, with worn or otherwise degraded throat feathers. Well, they are male Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, but I believe that the rest of that speculation is wrong. They are apparently typical males in non-breeding plumage! (Update: the orange-throated males seen in late summer apparently are worn – see my later post Progress on the Orange-throated hummingbird mystery – but the orange-throated specimens from the wintering grounds probably represent a nonbreeding plumage).

Hummingbird molt

Ruby-throated Hummingbird was thought to molt all of its feathers just once each year, in a complete molt on the wintering grounds that ended with the rapid replacement of all throat feathers just before the birds migrated north (Pyle, 1997). Then a model study by Donna Dittmann and Steve Cardiff (2009) used thousands of photographs of hummingbirds visiting their Louisiana backyard feeders to document a previously unknown summer molt in Ruby-throated Hummingbird. Wing and tail feathers are molted only once each year (on the wintering grounds) but the head and body feathers are replaced twice each year, once in the summer, and again in late winter.

When I read about this summer molt and the "extra" replacement of throat feathers, I wondered if there could be a connection to the odd orange-throated males that are seen each fall. If Ruby-throated Hummingbirds were only growing iridescent throat feathers once each year, just before migrating north in the spring, it's hard to explain a different throat color in the fall. But, if these hummingbirds are growing a set of feathers that will only be worn in the non-breeding season, it makes sense that there would be less selection for brilliant red throats at that season. Molting the throat feathers twice each year essentially allows the male hummingbirds to "go casual" for the winter and grow feathers that are less bright, without paying any social penalty for it. Could the orange throat be a recognizable winter plumage shown by some or all males?

The nonbreeding plumage of Ruby-throated Hummingbird

Adult male Ruby-throated Hummingbirds - three in breeding plumage (left) collected in April in Florida, and three in nonreeding plumage (right) collected in Oct-Nov in Mexico. Specimen use granted by Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University ©President and Fellows of Harvard College.

A survey of specimens at Harvard's Museum of Comparative Zoology confirms that all of the winter specimens there have a significantly different throat color than specimens collected in spring and early summer. The photo above shows three spring Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in "breeding color", with three winter birds in "nonbreeding color".

The color difference can be tricky to see. Like other iridescent colors it changes slightly as the angle of view changes. For the photo shown here I chose the angle that showed the most dramatic color difference, but from some other angles the colors appeared much more similar. Nevertheless, the color difference is consistent and definite. No winter males show the deep red color of the summer birds, and only a couple of summer birds approach the more orange throat color of the winter birds.1

More questions than answers

Currently the biggest question is this: Is the color difference in the orange throat really the result of molt, or is there some other explanation?2

And there are a lot of other questions:

Do any other North American hummingbirds have summer molts? If so, do they also have a recognizable non-breeding plumage?

Besides throat color, are there other parts of the body plumage that show differences between summer and winter plumages?

Do females show any difference between summer and winter plumages?

What is the evolutionary origin (and correct terminology) for these molts?3

Do Ruby-throated Hummingbirds undergo this summer molt wherever they are in eastern North America, or do they migrate to favored molting areas?

Do all of them molt before migration, or do some migrate to the wintering grounds and molt there?

Many of these questions could be answered by careful observations by backyard birders. This is yet another reminder that new discoveries are still waiting to be made, even among the most common backyard birds of eastern North America. A well-executed study like the one by Dittmann and Cardiff can lead to new discoveries anywhere, for any species. All it takes is curiosity and observation.

References

Dittmann, D. L. and S. W. Cardiff. 2009. The Alternate Plumage of the Ruby-throated Hummingbird. Birding 41: 32–35. http://www.aba.org/birding/v41n5p32.pdf continued here: aba.org/birding/v41n5p35w1.pdf

Howell, S. N. G. 2010. Molt in North American Birds. 267 pp. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Pyle, P. 1997. Identification Guide to North American Birds: Part I. Slate Creek Press. 731 pp.

Notes

Thanks to Masaharu Ishii for allowing use of his photo. Thanks to Peter Pyle and Donna Dittman for comments and discussion, and to Jeremiah Trimble and Harvard's MCZ for access to specimens.

The few summer birds showing orange throats may be one-year-olds in their first breeding plumage, or perhaps adult males that were less healthy or had lower hormone levels when their feathers were growing. Immature males in their first fall and winter also show this orange color on the few iridescent feathers they have acquired on their throats.Donna Dittmann (email) reports that during her study she did not see a color difference between old and new feathers on molting males in Louisiana. Furthermore, she says that comparing specimens of fresh fall males with worn summer males in the museum at LSU shows no difference in throat color, and that the only orange-throated specimens at LSU were collected in winter in Mexico (just like the orange-throated MCZ specimens). What does this mean? I don't know. The throat color of the MCZ winter specimens (all from Mexico and Central America) shows a clear and consistent difference from the spring specimens. If it's true that this difference is not apparent in Louisiana immediately after molting, then something must change in the next month or two as the birds travel to their wintering grounds. They can't go through another molt, but maybe the existing feathers change somehow. Any hypothesis would also need to explain the occasional orange-throated birds that are noticed all across the eastern US in early fall. It remains a mystery.For those who really like molt studies: see Dittmann and Cardiff (2009), and Howell (2010) for some discussion of molt terminology, and the debate is ongoing. If the wing and tail molt in winter is connected with the complete body molt in late winter, that must be the annual complete Prebasic molt. In that case this newly-discovered summer molt of body feathers must be the Prealternate. But if the summer molt of body feathers is connected to the winter molt of wing and tail feathers (with a pause for fall migration and restart on the wintering grounds), then that whole process would be the Prebasic molt, and the body molt in late winter is a separate event unconnected to the replacement of wing and tail feathers, and would be the Prealternate. This latter scenario is a better match for the "standard" molt cycles of birds, but hummingbirds are an unusual group, so there's no reason to assume that they comply with any standards of molt. The answer to those questions can probably best be found by studying the exact timing and extent of molts on the wintering grounds.

August 1, 2011

Possible hybrid Little x Snowy Egrets

Snowy-like egret with two long and sturdy head plumes like Little, see below for more photos. 10 May 1995. Hammonasset State Park, CT, USA, Photo copyright Ray Schwartz, used by permission..

A few records of "Snowy" Egrets with long head plumes have turned up in places where Little Egret has also occurred. Are they hybrids, or just rare variants of Snowy?

Update 6 Aug 2011 – I had overlooked Martin Reid's photos from Texas in May 1998 of a very similar long-plumed Snowy-like Egret. So obviously there is a record from Texas, where a Little Egret hybrid is far less likely to show up, and this seems to tilt the balance a little more towards pure Snowy Egret. In addition, Steve Mlodinov reports a long-plumed bird similar to the Antigua photos, from southern Baja California, Mexico. The plumes of the Connecticut and New Hampshire birds still look a little more sturdy than this, but it's hard to say for sure, and it becomes harder to argue that those are hybrids if the others are not….

Little Egret (Egretta garzetta) and Snowy Egret (Egretta thula) are extremely similar species occupying large areas of the Old World and New World, respectively. Since the 1980s (with a major influx in the early 1990s) Little Egret has been detected in small and increasing numbers in the West Indies, with breeding records on Barbados, and a few individuals have also appeared along the Atlantic coast of the US and Canada. Given their similarity in appearance and behavior, and the fact that some Little Egrets in eastern North America have stayed through the summer, associating with Snowy Egrets, hybridization is plausible. Copulation was observed in a mixed pair at Barbados in 1999 (fide Floyd Hayes, ID-Frontiers email 22 Apr 2008), but whether any hybrid offspring fledged is unknown.

For more details on the plumes of these two species see my post on Differences in plumes of Little and Snowy Egret.

The two species are so similar that detecting and identifying a hybrid is extremely difficult. The Connecticut, New Hampshire, and Antigua birds discussed here, a record from Florida, and one sight record from Trinidad are the only reports of possible hybrids ever published. It is possible that the Connecticut and three New Hampshire records could involve repeat sightings of one individual, but there is no way to know.

Records

10 May 1995, Hammonasset Beach State Park, CT, photo above and more below

28-29 Apr 1990, Hampton, NH, photos below

20 Apr 1997, Rye, NH1

1998, Newmarket, NH2

Apr 1993, Pinellas Co. FL,3

17-18 Apr 2008, Antigua, two or three birds, photo below (Jaramillo, 2008)

Trinidad4

May 1998, Fort Worth, Texas photos here: http://www.martinreid.com/Main%20website/egrets2.html

Photos of the Connecticut bird (above, and more below) show what is essentially a Snowy Egret (with yellow lores, bushy crest), except for the two long lanceolate plumes that extend well beyond the normal Snowy Egret crest. Snowy Egrets often show a few slightly longer feathers in the midst of their lacy crest, and the lacy plumes can sometimes clump together to form more obvious strands, but the individual feathers are always extremely flimsy and lacy. The extreme length of these plumes, however, and the fact that they are bending in the wind without breaking up, seems so far beyond the normal range of variation in Snowy Egret that I think a hybrid is the more plausible explanation.

Snowy-like Egret with two long plumes, Hampton, New Hampshire, 29 April 1990. Photo copyright Steve Mirick, used by permission.

The 1990 New Hampshire bird (above, and more photos below) shows a similar bushy crest with two long lanceolate plumes. This bird has darker orange facial skin as in the high-breeding condition of Snowy and Little Egrets, which might indicate that it was nesting somewhere in the area. The very long plumes blown up by the wind are clearly not the typical fine lacy plumes of Snowy Egret.

Snowy-like Egret with several unusually long head plumes. Antigua. Photo copyright Alvaro Jaramillo, used by permission.

Photos of one bird from Antigua (where at least two or three similar individuals were thought to be present) show a Snowy-like Egret with lacy crest and several much longer, but still lacy, feathers. The Texas bird also seems to show long but somewhat lacy plumes. Photos of these birds show long plumes, but with a more Snowy-like feather structure than the Connecticut and New Hampshire birds show. It is impossible to determine the actual feather structure of the latter birds, but the plumes look thicker and more sturdy, more like Little Egret.

Pros and Cons

The main argument against these being hybrids is that they do not show any sign of Little Egret influence other than the long head plumes. BUT, the two species are so similar in all respects, there is no reason to expect a hybrid to stand out in any way other than head plumes. Some Little Egrets are larger than Snowy Egrets, but overall size and bill size overlaps extensively. The back plumes are slightly less curled on Little. The breast plumes are slightly thicker on Little. The facial skin is often gray on Little, but turns yellow to red in breeding season. It is plausible that a hybrid would show yellow loral skin all year and no detectable difference in size, back plumes, or breast plumes.

One point in favor of the hybrid theory is that they have only been found in places where Little Egret is known to occur with Snowy. BUT, maybe that's simply because in those places people are looking very hard for Little Egret and notice the long head plumes. These birds would be easily overlooked in other places where Little Egret is not actively searched for. If birders looked this hard for Little Egret in Texas, for example, would they find long-plumed Snowys there as well? Some people do look for Little Egret in Texas, and have never reported plumes like this. Alvaro Jaramillo, after seeing possible hybrids on Antigua, has looked very closely at Snowy Egrets in California and elsewhere and has not seen any with plumes like the Antigua birds. Many birders have watched for Little Egret in Florida, and only one "long-plumed Snowy" has been found there.

Conclusion

My guess is that the Connecticut and New Hampshire birds are hybrids. The structure of the plumes seems to show the broad, lanceolate shape typical of Little Egret. The Antigua bird certainly shows long plumes, and may be a hybrid, but the structure of the plumes looks similar to typical Snowy Egret, and this may represent the extreme of length in Snowy Egret plumes.

This question might never be fully resolved unless one of these odd birds can be captured (or a feather retrieved) for DNA testing. If observers in other parts of the range of Snowy Egret can document that similar individuals do occur in California, Texas, etc, that would suggest that the plumes are a rare variant of Snowy and not a hybrid feature.

Photo Gallery

10 May 1995. Hammonasset State Park, CT, USA, Photo copyright Ray Schwartz, used by permission..

10 May 1995. Hammonasset State Park, CT, USA, Photo copyright Ray Schwartz, used by permission..

10 May 1995. Hammonasset State Park, CT, USA, Photo copyright Ray Schwartz, used by permission..

10 May 1995. Hammonasset State Park, CT, USA, Photo copyright Ray Schwartz, used by permission..

10 May 1995. Hammonasset State Park, CT, USA, Photo copyright Ray Schwartz, used by permission..

10 May 1995. Hammonasset State Park, CT, USA, Photo copyright Ray Schwartz, used by permission..

Snowy-like egret with two long and sturdy head plumes like Little. 10 May 1995. Hammonasset State Park, CT, USA, Photo copyright Ray Schwartz, used by permission..

10 May 1995. Hammonasset State Park, CT, USA, Photo copyright Ray Schwartz, used by permission..

10 May 1995. Hammonasset State Park, CT, USA, Photo copyright Ray Schwartz, used by permission..

Snowy-like Egret with long head plumes. Hammonasset State Park, CT. Photo copyright Mark Szantyr, used by permission.

Hampton, New Hampshire, 29 April 1990. Photo copyright Steve Mirick, used by permission.

Hampton, New Hampshire, 29 April 1990. Photo copyright Steve Mirick, used by permission.

Hampton, New Hampshire, 29 April 1990. Photo copyright Steve Mirick, used by permission.

Snowy-like Egret with two long plumes, New Hampshire, April 1990. Photo copyright Steve Mirick, used by permission.

Snowy-like Egret with several unusually long head plumes. Antigua. Photo copyright Alvaro Jaramillo, used by permission.

References

Wilson, A. 1999. Separation of Little Egret (Egretta garzetta) from Snowy Egret (E. thula). http://www.oceanwanderers.com/LTEGRT.html – discussion and photos of a Little Egret in Delaware.

Hayes, F. IDENTIFICATION ESSAY: Little Egret (Egretta garzetta) and Snowy Egret (E. thula). http://secrb.trinidadbirding.com/idlittlesnowyegret.html – detailed notes and many photos from Trinidad.

Anonymous. Snowy Egret Egretta thula or Little Egret Egretta garzetta? http://azores.seawatching.net/index.php?page=egret Discussion of the identification of vagrants on the Azores

Jaramillo, A. 2008. CARIBBEAN EGRETS: LITTLE EGRETS. http://www.coastside.net/chucao/gulls/egrets.htm – photos showing variation of Little Egret in the Lesser Antilles, and one possible hybrid x Snowy Egret very similar to the Connecticut bird.

Reid. M. http://www.martinreid.com/Main%20website/egrets.html – Martin Reid's web pages with lots of discussion of variation in Snowy Egret as it applies to Little Egret identification in Texas;

Massiah, E. (1996) Identification of Snowy Egret and Little Egret. Birding World 9(11): 434-444.

Grant, P. J. et al., (1980) Bare-part colour of Snowy and Little Egrets. British Birds 73: 39-40.

McLaren, I. A. (1989) Thoughts on North American Little Egrets. Birding 21: 284-287.

Sibley, D. (1997) Snowy vs Little Egret. ID-Frontiers: 27 Aug 1997.

McCarthy, E. M. 2006. Handbook of avian hybrids of the world. Oxford Univ. Press. 583 pp.

Notes

Thanks to Mark Szantyr, Steve Mirick, Alvaro Jaramillo, and Louis Bevier for photos and help with this note.

fide Steve Mirickfide Steve MirickThe record from Florida involves a long-plumed egret identified as a Little. The Florida bird records committee did not accept it as such, saying that it could have been a Snowy with long plumes (brief discussion in pdf here http://www.fosbirds.org/sites/default/files/FFNs/FFNv24n4p123-134Anderson-FOSRC12.pdf photos apparently on file in Florida, I have not seen them).sight record reported in McCarthy, 2006, no other details

David Allen Sibley's Blog

- David Allen Sibley's profile

- 151 followers