David Allen Sibley's Blog, page 21

January 20, 2012

Sibley eGuide available for Kindle Fire

The Sibley eGuide to birds was recently adapted for the Kindle Fire tablet (and still works on other Android OS devices). You can find it at the Amazon app store.

In other news an update for the Android OS is coming soon that will (among other things) remove the annoying requirement to verify over the network every 45 days, so the app will be fully functional and never need a network connection except once when it is installed.

Also, the developers tell me to expect an announcement about a Windows Phone 7 version soon.

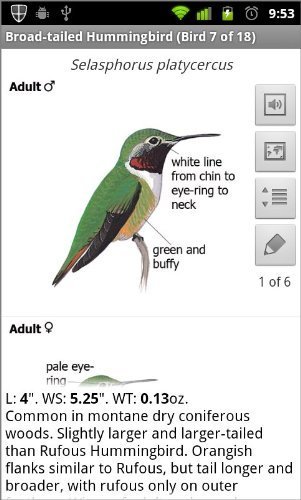

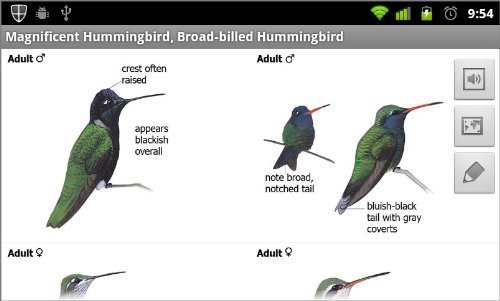

Screen Shots:

Broad-tailed Hummingbird as it appears on the Kindle screen.

Magnificent and Broad-billed Hummingbirds using the "compare" feature in landscape mode on the Kindle Fire.

Identifying sleeping female goldeneyes

Like many other species of ducks that are distinguished by head shape, Common and Barrow's Goldeneyes are at least as easy to tell apart when sleeping as when they are awake. Birds that are awake and active change head shape a lot as they go from relaxed to alert to diving, but sleeping birds are always about the same. The image below shows the typical appearance of the two species. If you like quizzes you can try to identify them before you read the next paragraph, or just read on for the answer.

Two species of female goldeneyes showing differences in head shape. See text for identification and discussion. Original gouache painting copyright David Sibley.

Differences in head shape mainly involve the placement and shape of the peak of the head. On Barrow's the peak is farther forward, and the crown is low, flat, and sloping back to the "mane". On Common the peak is farther back and taller, rising from the forehead to a rounded triangular peak, then sloping sharply down to the "mane". In addition, the forehead of Barrow's is a little steeper and bulging, and the "mane" of Barrow's is a little longer, all combining to make the head look low and oval, while Common has a more triangular or circular head. In the painting here it's Common above and Barrow's below.

If only they would sleep more often…

January 19, 2012

Distinguishing male and female American Goldfinches

The underside of the tail of four different American Goldfinches - two males and two females. See text for details. Photographs of birds trapped for banding in Concord, MA, copyright David Sibley.

For much of the year, distinguishing male and female American Goldfinches is easy (when the males show their brilliant yellow summer plumage, about March through September). Even in January and February many males have a few bright yellow feathers showing, but otherwise the gray-brown nonbreeding males can be hard to tell from females. There is very little difference between immatures and adults of each sex.

Males have really black wings with bright wingbars and feather edges, while the females have duller brownish-black wings with buffy or brownish-white wingbars and edges. This is pretty easy to judge, but it requires a bit of experience and judgment.

For a more objective and reliable difference, look at the underside of the tail, which is easily seen when birds are sitting on a feeder. Males have blackish tail feathers with well-defined white spots, females grayish feathers blending into dull white spots. Once you've confirmed the sex of a bird by the tail pattern, take a minute to look at the wings, the body plumage, bill and leg color, etc., and you'll soon become an expert on goldfinch plumage variation.

January 17, 2012

Subspecies of Scaled Quail

There are four named subspecies of Scaled Quail, three in the US and one in Mexico. The subspecies found in southern Texas is distinctly different from the other three, at least in adult male plumage, and makes the list of field identifiable subspecies. Here's a quick summary of the differences, based on study of specimens at Harvard's MCZ, and numerous photos. Some field testing is needed, and figuring out where (and how much) the subspecies intergrade is important. No difference in voice has ever been mentioned, but that's worth checking out.

Basically, any bird with a chestnut belly is safely identified as the south Texas subspecies castanogastris. Birds without a chestnut belly could be another subspecies, or females or immatures of castanogastris, and you'll have to look at other details to identify them. Vagrants are unlikely to occur, so range will be a reliable clue to identification, but in order to work out the range we'll have to identify a lot of birds…

Males of the two forms of Scaled Quail found in the US: pale-bellied subspecies pallida and hargravei (left) in most of the species' range, and chestnut-bellied subspecies castanogastris (right) found in southern Texas. Original gouache panting copyright David Sibley.

Males differ very slightly in overall color and darkness, probably not enough to be useful in the field except in direct comparison (which is unlikely to happen in the wild). Identification will have to be based on the color of the belly and undertail coverts.

Males: southern Texas vs Arizona-New Mexico

center of lower belly with dark chestnut or maroon-brown patch, may be small or irregular (vs center of belly pale buff)

belly surrounding chestnut patch tinged strongly orange-buff, fading to cream-buff outwards (vs slightly orange-buff in center of belly where TX birds have chestnut, fading to off-white outwards)

undertail coverts with dark brownish markings, washed orange-brown to rust (vs paler gray-brown markings with cream-colored edges)

neck and breast darker gray, forming distinct gray breastband

crown and cheeks grayer and darker (vs ashy brown)

slightly darker overall

slightly darker and more brownish on back

tail darker gray above

throat slightly darker and more orange-brown

Females differ very slightly in overall color similar to male but less obvious, and south Texas females don't really show any trace of the chestnut belly patch, so the best field mark for males is not useful on females. They do seem to show a difference in throat pattern.

Females: southern Texas vs Arizona-New Mexico

throat distinctly streaked (vs smooth pale buff-gray)

belly and under tail coverts slightly more orange toned

breast and neck very slightly darker

upperparts darker and warmer brown, especiaily on scapulars and upper tail coverts

January 13, 2012

Do "dwarf" birds exist?

A recent discussion on the ID-Frontiers listserver involved an immature gull photographed in Utah (photo by Norman Jenson here). The consensus (and I agree) is that it is a Western Gull based on plumage and shape. But questions arise from the fact that it looks barely larger than the California Gulls next to it – abnormally small for a Western Gull.

Those of us who didn't see the bird in life might like to ignore the apparent size as an illusion of the photographs, but the observers report that the bird really did look small. Can it still be a Western Gull? Yes. Since size is the only thing suggesting that it's not a Western Gull, I think we have to go with the identification as a very small Western Gull. But is it a "dwarf", or just the small extreme of normal variation?

Terminology

Much of the discussion about this bird and other unusually small individuals has referred to them as "runts", but technically that is the wrong term. A runt usually means a young animal, still growing (the smallest of a litter of puppies, for example), that is smaller than its siblings. This is common in birds, caused by poor health or poor nutrition, but if runts survive they can grow to full size indistinguishable from their nest-mates. Unusually small adult birds should be called "dwarfs".1

Peter Pyle reported on ID-Frontiers that gull expert Larry Spear held the opinion that there is no such thing as a dwarf bird, and that an individual like the Utah gull is just the rarely seen tail end of normal variation in Western Gull. In the same way that full-grown humans under five feet (or over seven feet) tall simply represent the extremes of normal variation.

In humans dwarfism is neither well-defined nor simple. Dwarfism is defined by an arbitrary threshold along the continuum of adult sizes, and over 200 causes of dwarfism have been identified (Wikipedia). It seems likely that birds are similar.

An informative study by Hicks (1934; thanks to Steve Mlodinow for the tip) carefully examined over 10,000 starlings in the hand. Unusually small and large birds that caught the researchers' attention were measured. In this sample of 10,000 birds there were seven "giant" and six "dwarf" individuals that measured about 10% larger or smaller than the average of "normal" birds measured.

Unfortunately not all 10,000 birds were measured, only about 500 randomly selected "normal" birds were carefully measured, along with the 13 individuals that were strikingly large or small. Only total length measurements are given, but the largest dwarf measured only 9mm (about 5%) smaller than the smallest "normal" female. Furthermore, all of the giant birds were males (the larger sex), and five of the six dwarfs were females. It seems likely that, if all 10,000 individuals had been carefully measured, the data would fill in the relatively small gaps between the normal birds and the dwarf and giant birds.

Another documented case, with direct application to identification, is that of an unusually small Great Crested Flycatcher trapped and collected in New Jersey (Murray, 1971). This individual was immediately suspected of being an Ash-throated Flycatcher based on size, but careful study confirmed it to be a very small Great Crested. Its measurements are over 10% smaller than the average for Great Crested, and smaller than the minimum given by Pyle (1997). It is even a little too small for Ash-throated Flycatcher! In addition, it has a disproportionately short tail, while its wing measurement is just 1mm below the minimum for Ash-throated, its tail measures 9.5mm shorter than the smallest Ash-throated measured by Pyle.

It's really a semantic question. Documented cases of unusually small birds exist and must be considered when identifying rare species. We could set an arbitrary threshold that categorizes them as "dwarfs" or just consider them the extremes of normal variation. The impact on bird identification is the same either way.

References

Coulter, M.C., 1982. Development of a Runt Common Tern Chick. Journal of Field Ornithology, 53(3), pp.276–279.

Hicks, L.E., 1934. Individual and sexual variations in the European Starling. Bird-Banding, 5(3), pp.103–118.

Murray, B.G., 1971. A Small Great Crested Flycatcher: A Problem in Identification. Bird-Banding, 42(2), pp.119–119.

Pyle, P. et al., 1997. Identification Guide to North American Birds: Columbidae to Ploceidae, Slate Creek Press.

A runt Common Tern studied by Coulter (1982) was the smallest in the nest, and seemed unlikely to survive, but eventually grew to normal size and fledged, albeit about ten days later than its nest-mates. On the other hand, continued poor nutrition results in birds that never reach full size and remain smaller than normal, as several studies on Snow and Canada Geese have shown.

January 12, 2012

Want to go birding in Montana in May-June?

There are still a few places left on my 2012 birding workshops 27 May to 8 June 2012 at Pine Butte Guest Ranch in Montana. It's a great opportunity to visit a spectacular place, learn some birding skills and techniques, meet some nice people, and support the work of The Nature Conservancy

In 2010 we were lucky enough to find a family of Northern Hawk-Owls, including this fledgling, establishing one of the southernmost nesting records in North America. Photo copyright David Sibley.

During the week we'll spend our days in the field, and evenings at the lodge. And we'll have informal discussions and a couple of more formal presentations about things like how to draw birds, identifying birds by song, the psychology of perception and bird identification, bird topography, molt and plumages, wing shape and flight, and more.

Lazuli Buntings nest in willow and aspen thickets along the river and also around mountain meadows. Photo copyright David Sibley.

A male Rufous Hummingbird moves to defend its feeder, which happens to be on the porch of the Pine Butte Guest Ranch. Photo copyright David Sibley.

I'll be joined for part of the time by John Carlson, an excellent ornithologist and photographer from Montana, and also by artist and birder Keith Hansen, from Bolinas, California, and it promises to be a really fun time.

The main lodge at Pine Butte Guest Ranch. Right around the building it's common to see Mountain Bluebird, Rufous Hummingbird, Western Tanager, etc. Black Bear and Grizzly Bear have been seen occasionally on the ridge visible behind the lodge. Photo copyright David Sibley.

We spend a lot of time hiking (short distances), but the pace is relaxed, with early morning birding right around the ranch, short drives, no change of lodging, and no real "target" species, which allows time to study and discuss whatever bird is cooperative – a Red-necked Grebe, Rufous Hummingbird, or Raven all provide opportunities for learning. The food and accommodations are excellent, and the setting is unmatched.

I hope you can join us! More info.1

This is some of the wildest and most scenic land in the lower 48 states. This photo is taken from the top of Pine Butte, looking west towards the Rocky Mountain Front (where the ranch is located). Habitat ranges from prairie grassland and fen wetland, through Limber Pine, Douglas-Fir, Spruce-Fir forest, and up to treeline, all within a space of a few miles, and the birds are just as diverse.

Note that two six-day workshops are offered, but I will not be present for the first two days of the first workshop or the last two days of the second workshop. In my absence you will be in the very capable hands of the staff naturalists as well as John Carlson (week 1) and Keith Hansen (week 2).

December 7, 2011

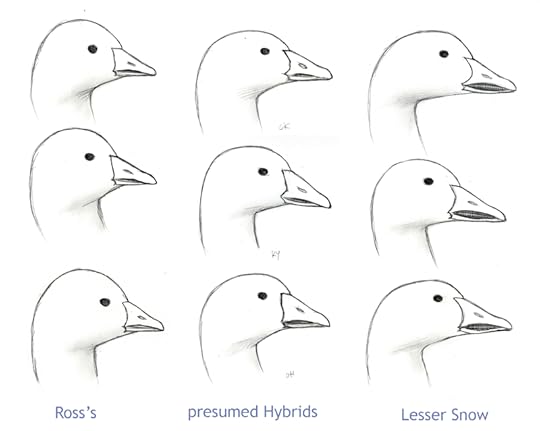

Identification of white geese

Recent discussion of the identification of a white goose in Ohio (beginning here) prompted me to put together some sketches of bill shapes of Ross's and Snow Geese, since bill shape is the most significant difference between those species. It was a very interesting exercise, as each species is surprisingly consistent in the relative size and proportions of head and bill, suggesting that the overall impression of bill size is a fairly reliable (though subjective) feature, and there are some other details that allow a more objective identification.

Tracings of head and bill shapes of white geese, adjusted so head sizes match, to emphasize differences in proportions. Original pencil sketches copyright David Sibley.

The middle column of presumed hybrids is traced from three individual birds. In the middle is one from Kentucky (photograph by David Roemer here) that seems to be a straightforward intermediate bird and almost certainly a hybrid. The top bird in the presumed hybrids is from Oklahoma (traced from a photograph by Victor Fazio here) and the bottom presumed hybrid is the contentious Ohio individual (traced from a photo by Matt Valencic here).

Besides absolute bill size, the features that seem most useful for distinguishing Ross's from Snow and from potential hybrids are:

faint or absent "grin patch" – Ross's usually show a small and inconspicuous dark line, Snow Geese an obvious black oval. This is related to the following…

lower mandible nearly straight on Ross's, strongly curved on Snow, and slightly curved on hybrids

border of feathering at base of bill relatively straight on Ross's, curved on Snow – this is somewhat variable in Ross's, and seems even more variable in hybrids (if these three are really hybrids), but Snow always has the border strongly curved, and Ross's straight or slightly curved.

As a measure of bill length, on Ross's the bill is always obviously shorter than the thickness at the top of the neck, on Snow the bill length is greater than neck thickness, and hybrids intermediate.

Round head – There is little difference in forehead slope or crown shape, the perception of a different head shape seems to come from the fact that the head of Ross's can be described as a circle, while on Snow Goose (and hybrids) the head is more oval.

I still maintain that the Ohio bird fits into the "hybrid" column better than the Ross's column. There must be backcrosses and maybe even pure Ross's Geese that blur the distinction between these categories as illustrated, and discovering that will require a more detailed study of variation in a large number of geese. Hopefully these sketches will help the discussion move forward.

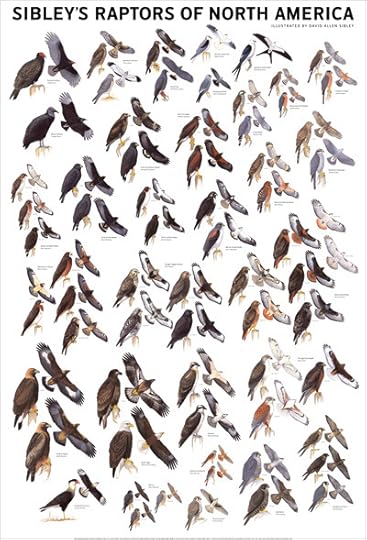

New Raptors poster and other gift ideas

New from Scott & Nix – Sibley's Raptors of North America poster

List price $29.95

24 x 36″

Buy from Amazon

Buy from Scott & Nix, framed or unframed

Other recent products

Audubon's Birds of America (Facsimile) – the first modern reproduction of this iconic work. The Natural History Museum of London made new high-resolution scans of the complete double elephant folio in their collection, and the result is outstanding. With an introduction by David Allen Sibley.

Audubon's Birds of America (Facsimile) – the first modern reproduction of this iconic work. The Natural History Museum of London made new high-resolution scans of the complete double elephant folio in their collection, and the result is outstanding. With an introduction by David Allen Sibley.

List Price $80

Buy from Amazon

And more…

2012 Weekly Engagement Calendar

Also… The Sibley eGuide has just been updated for iPad, and check out the Shop for other books, posters, t-shirts, and more.

December 5, 2011

eGuide update – Redesigned for iPad!

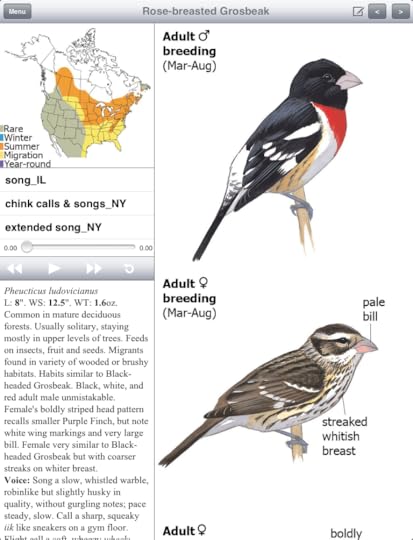

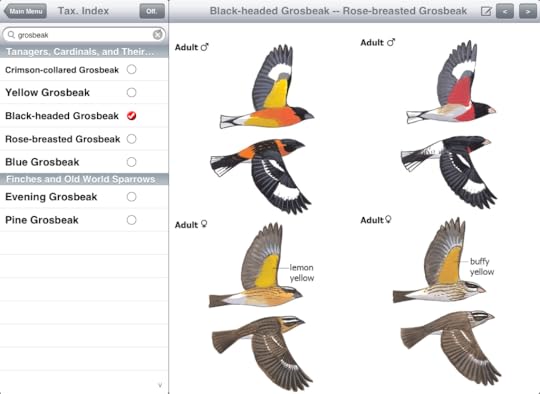

The Sibley eGude to Birds for iPhone and iPad has been updated to be a universal app. The new version takes advantage of the full screen of the iPad to show images and maps at high resolution, show all information (images, text, map, and audio) on a single screen, and in landscape orientation allows viewing the species list and species account at the same time for quick navigation.

Rose-breasted Grosbeak in the new iPad layout with images, text, map, and audio all together. Scroll up and down to see all images. Tap any image or map to view full screen. Swipe left or right to see previous or next species.

The iPad version in landscape orientation comparing Black-headed and Rose-breasted Grosbeaks. You can scroll the images of each species independently up and down, swipe left or right for previous or next species, and select any other species from the list on the left. Tapping any image shows it full screen.

Other projects in the works include a version for Windows Phone 7, a version for Amazon's Kindle Fire, and various minor improvements to content and navigation.

A few users have reported issues with the new version on the iPod Touch. If this is you please contact us and we'll get it sorted out. Also note that the update might wipe out any bird list records you have in the app, so make sure you download those and save them before installing the new version. At this time we recommend using the listing function in the app only for temporary record-keeping because of this, for example to keep a list for a day or a trip, then download that data and archive it in another program.

The 2011 name changes announced by the AOU will appear in the next update.

October 27, 2011

Overconfidence

A recent article by Tim Enthoven in the New York Times – Don't Blink! The Hazards of Confidence – offers some fascinating thoughts on judgment, expertise, and illusions of confidence, and it's an interesting perspective from which to examine the challenge of bird identification.

One of his key points is that confidence does not arise from a careful assessment of probabilities.

"Confidence is a feeling, one determined mostly by the coherence of the story and by the ease with which it comes to mind, even when the evidence for the story is sparse and unreliable. The bias toward coherence favors overconfidence. An individual who expresses high confidence probably has a good story, which may or may not be true."

Our confidence in bird identification is often based on fleeting glimpses, subjective impressions, and snap judgments, yet we still say we are "one-hundred-percent sure". This confidence, according to Enthoven, comes from the tidy narrative we construct around our sighting, more than from the actual observation. The real danger of this confidence is that it prevents us from recognizing our mistakes. Overconfidence leads us to reject the possibility of error and instead adapt our story to emphasize our correctness. Overconfidence, ironically, can be one of the biggest barriers to developing expertise.

Admitting mistakes forces us to reconsider and rewrite the narrative, and we get better at bird identification by developing a richer and more nuanced library of scenarios to describe our sightings. In his conclusion Enthoven says: "True intuitive expertise is learned from prolonged experience with good feedback on mistakes."

In other words, the best way to develop true expertise as a birder is to spend long hours in the field, to be alerted to your mistakes quickly, and to review them unflinchingly. Unfortunately, most of our mistakes as birders disappear into the distance, and we never have a clue that a mistake was made, let alone what it might have been. The ones we do know about are often pointed out by other birders, and at that point most people get defensive.

That's normal, but also counterproductive. Mistakes happen, and they provide excellent learning opportunities, but only if we are open to admitting and examining them.

David Allen Sibley's Blog

- David Allen Sibley's profile

- 151 followers