David Allen Sibley's Blog, page 12

July 26, 2012

Quiz 43: Still more songbird legs and feet

Here are three more songbirds showing some of the variation in legs and feet.

With thanks, again, to Brian E. Small for providing the beautiful photos. You can see lots more at his website.

Legs and feet of songbirds 3

Please wait while the activity loads. If this activity does not load, try refreshing your browser. Also, this page requires javascript. Please visit using a browser with javascript enabled.

If loading fails, click here to try again

Congratulations - you have completed Legs and feet of songbirds 3.

You scored %%SCORE%% out of %%TOTAL%%.

Your performance has been rated as %%RATING%%

Your answers are highlighted below.

Question 1

Wood-WarblerOrioleSparrowThrushQuestion 1 Explanation:Baltimore Oriole - Orioles, being in the same family as blackbirds and grackles, have relatively heavy legs and strong feet. All of the orioles have blue-gray legs, while all blackbirds have black legs.

Question 2

Question 2

TowheeThrushOrioleWood-WarblerQuestion 2 Explanation:Spotted Towhee - Merely a large and heavy sparrow, with the sparrow characteristics of strong legs and feet with very strong claws, just a bit more so.

Question 3

Question 3

ThrushWood-WarblerOrioleSparrowQuestion 3 Explanation:Hermit Thrush - The woodland thrushes have very long and thin legs, with slender toes and weak claws, similar to wood-warblers. American Robin and the larger thrushes have somewhat sturdier legs.

Once you are finished, click the button below. Any items you have not completed will be marked incorrect.

Get Results

There are 3 questions to complete.

You have completed

questions

question

Your score is

Correct

Wrong

Partial-Credit

You have not finished your quiz. If you leave this page, your progress will be lost.

Correct Answer

You Selected

Not Attempted

Final Score on Quiz

Attempted Questions Correct

Attempted Questions Wrong

Questions Not Attempted

Total Questions on Quiz

Question Details

Results

Date

Score

Time allowed

minutes

seconds

Time used

Answer Choice(s) Selected

Question Text

All doneNeed more practice!Keep trying!Not bad!Good work!Perfect!

July 25, 2012

Is it hard for hummingbirds to hover in the rain?

Not really. A recently-published study used high-speed video of hummingbirds hovering in simulated rain to investigate questions of how hard it is to stay airborne while simultaneously getting wet (and heavier) and getting pelted with water drops that must be a significant blow to their 4 gram bodies.

The conclusion is that the birds have little trouble handling rain. Their flight was essentially unchanged in light to moderate rain, and in heavy rain they simply turned their body more horizontal, beat the wings more quickly and in a shorter arc. Water does not adhere to their feathers and they can quickly shake off any droplets that do. Drops that hit the bird’s wings simply flex the feathers and bounce off. The conclusion is that heavy rain only adds a little to the energetic costs of flight, and is not really a problem for a healthy hummingbird.

References

Ortega-Jimenez, V.M. & Dudley, R., 2012. Flying in the rain: hovering performance of Anna’s hummingbirds under varied precipitation. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/early/2012/07/11/rspb.2012.1285

http://blogs.nature.com/news/2012/07/hummingbirds-dont-mind-the-rain.html

A Yellow Purple Finch in Ontario

Thanks to reader Skip Pothier for sending in these photos. They show a Purple Finch with yellow color instead of red. My first thought was to call it a male that didn’t develop the full red pigment (a similar variant due to poor diet and/or poor health is fairly common in male House Finches) but the answer here may not be so simple.

Yellowish Purple Finch, Port Perry, ON. 11 July 2012. Photos copyright Skip Pothier.

Yellowish Purple Finch, Port Perry, ON. 11 July 2012. Photos copyright Skip Pothier.

Yellowish Purple Finch, Port Perry, ON. 11 July 2012. Photos copyright Skip Pothier.

Yellowish Purple Finch, Port Perry, ON. 11 July 2012. Photos copyright Skip Pothier.

Yellowish Purple Finch (left) with normal male Purple Finch, Port Perry, ON. 11 July 2012. Photos copyright Skip Pothier.

Birds get red and yellow pigments from carotenoid compounds in their food, so a diet that doesn’t include enough carotenoids will lead to a bird with weaker color. The same carotenoid chemicals are also important for immune system function, so a sick bird can also show weaker color. Even if it gets lots of carotenoids in its diet, it will use them to fight disease and won’t have enough left to color the feathers.

On this bird, however, the explanation may not be that simple. On closer study I notice that it shows some thin streaking on the sides of the breast. This is more than a male would usually have, but far less than a typical female. This kind of variation in streaking (which involves melanin pigments) is usually controlled hormonally – adult males with lots of testosterone would grow breast feathers with no streaks, all other birds (females and immature males) grow feathers with broad brown streaks.

If this bird is hormonally intermediate, that could also conceivably explain the yellow color. It could be a male that was not producing enough testosterone as the new feathers grew during its last molt, or it could be a female producing a lot of testosterone. The existence of “male-like females” is known in waterfowl, and those are generally assumed to be older birds that grow feathers with some male-like colors and patterns. I’m not sure how we could distinguish a male from a female in these photos, given that the bird is abnormal.

As mentioned above, yellow color is fairly common in male House Finches, with birds showing a full range of color variation from red, to orange, to yellow, but no obvious differences in plumage pattern, suggesting it involves only carotenoids and is all diet-related. In Purple Finch yellow color is very rare, and often comes along with abnormal streaking, which may mean that it is hormonal.

Why don’t male Purple Finches show a simple “carotenoid-limited” yellowish color more often? Are Purple Finches healthier than House Finches? Do they have an easier time getting the necessary carotenoids in their diets? Or is there a fundamental difference in the mechanism of red coloration in the two species?

Some other examples of yellow Purple Finches from around the webBelow is one photo apparently an Eastern bird in Jan 2010 – photo copyright Stanley York; here alongside a typical female showing the difference in extent of streaking on the breast. Click to see the full size photo on Flickr.

Below is an Eastern bird from NS in May 2010; photo copyright Maxine Quinton. Click to see the original photo and more examples on Flickr.

http://www.redhawksquest.com/?p=1472 – apparently a Western bird in Feb 2009 (click the link then scroll down for photos). This looks more like a male that has simply reduced the normal red color to orange.

Thanks to Skip Pothier for sending the photos and for help with web research.

July 24, 2012

Name changes of birds in the 2012 AOU supplement

With the annual publication of the supplement to the AOU checklist, here is a listing of the changes to names in the Sibley Guide to Birds. There were a lot of other changes announced to names of neotropical birds, which are not discussed here. There were also some big changes in the sequence of species and families, which will be the subject of an upcoming post or two.

A pdf of the supplement can be seen here: http://www.aou.org/auk/content/129/3/0573-0588.pdf

One split affects the species count

Scripps’s Murrelet Synthliboramphus scrippsi – called “Northern” in the Sibley Guide

Guadalupe Murrelet Synthliboramphus hypoleucus – called “Southern” in the Sibley Guide

Formerly lumped as Xantus’s Murrelet Synthliboramphus scrippsi, now split into two species, both of which get new common names. This split has been anticipated for a long time. Both are found in the US and are fully covered in the Sibley Guide to Birds.

Splits of extralimital species

Audubon’s Shearwater is split (Galapagos Shearwater is now a full species) but only Audubon’s occurs in North America, and it retains the same name as before.

Gray Hawk is split into two species, but only one occurs in North America, and that species retains the common name Gray Hawk, but with a new scientific name Buteo plagiatus. The more southern Gray-lined Hawk does not occur in our area.

Changes in genera leading to name changes

The genus Stellula no longer exists, being merged into the genus Selasphorus, so Calliope Hummingbird, formerly Stellula calliope, is now:

Calliope Hummingbird Selasphorus calliope

Four species of North American nightjars were formerly in the genus Caprimulgus, but all of the native North American species are now placed in the new genus Antrostomus. The genus Caprimulgus remains on the North American list by virtue of a single record of an Old World species, Grey Nightjar, in the Aleutians.

Chuck-will’s-widow Antrostomus carolinensis

Buff-collared Nightjar Antrostomus ridgwayi

Eastern Whip-poor-will Antrostomus vociferus

Mexican Whip-poor-will Antrostomus arizonae

The genus Thryothorus is now reserved solely for Carolina Wren, and the other (mostly tropical) species in that genus are moved into new genera. The only one on the North American list is:

Sinaloa Wren Thryophilus sinaloa

New DNA evidence shows that Sage Sparrow (formerly Amphispiza belli) is not closely related to other species in that genus, such as Black-throated Sparrow. It becomes the sole member of a new genus:

Sage Sparrow Artemisiospiza belli

Three species of finches formerly in the genus *Carpodacus” are moved into a new genus, based on DNA evidence. The genus Carpodacus is now reserved for Old World species, including Common Rosefinch, while the New World species are placed in the new genus Haemorhous.

Purple Finch Haemorhous purpureus

Cassin’s Finch Haemorhous cassinii

House Finch Haemorhous mexicanus

A few other minor changes in names

Indian Peafowl Pavo cristatus, formerly Common Peafowl

Purple Gallinule Porphyrio martinicus, formerly P. martinica

Island Canary Serinus canaria, formerly Common Canary

There are also quite a few changes of sequence, with hummingbirds and some other families having genera and species shuffled around. The biggest changes are in the sequence of the orders Falcons and parrots, which are moved to come just before the Passerines (just after woodpeckers). That’s a relatively small move for parrots, but a huge move for Falcons. Not only does it put them in a whole new section of the list, but it moves them away from the hawks, and I suspect that will be the hardest thing for people to accept.

Interesting glimpses into the process

The proposal to split Savannah Sparrow failed by the narrowest of margins, with seven votes in favor and 3 against. Usually this would be enough to pass, but the comments reveal that, while there were seven votes in favor of a split, there was no agreement on how to split the species, and those seven members voted for four different options. Clearly there is a general feeling that there is more than one species of Savannah Sparrow, but until there is a little more clarity on where the divisions should be made, and how many, we will continue to have one species.

The Savannah sparrow proposal is in this pdf file: http://www.aou.org/committees/nacc/proposals/2011-C.pdf

Comments on the Savannah Sparrow proposal are here: http://www.aou.org/committees/nacc/proposals/2011_C_votes_web.php#2011-C–9

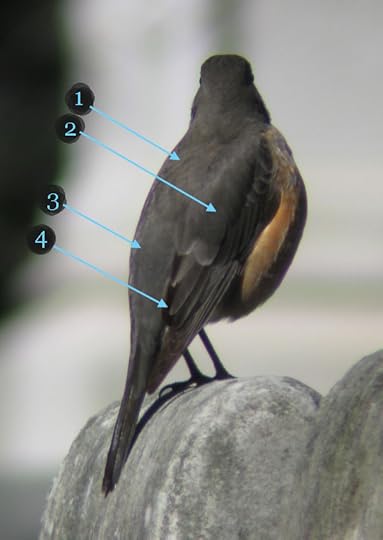

Quiz 42: More topography of the upperparts

Here is another quiz showing a bird viewed from behind, with questions about the feather groups that are visible. Notice how the contours of the back define the feather groups.

Photo copyright David Sibley

More feather topography

Please wait while the activity loads. If this activity does not load, try refreshing your browser. Also, this page requires javascript. Please visit using a browser with javascript enabled.

If loading fails, click here to try again

Congratulations - you have completed More feather topography.

You scored %%SCORE%% out of %%TOTAL%%.

Your performance has been rated as %%RATING%%

Your answers are highlighted below.

Question 1The feathers labeled 1 are: rumpscapularsnapemantleQuestion 2The feathers labeled 2 are the:greater covertsrumpmantle scapularsQuestion 3The feathers labeled 3 are the:scapularsrumpmantleuppertail covertsQuestion 4The feathers labeled 4 are the:uppertail covertsscapularssecondariesrumpQuestion 5The species is:Eastern BluebirdBlack-headed GrosbeakNorthern CardinalAmerican Robin

Once you are finished, click the button below. Any items you have not completed will be marked incorrect.

Get Results

There are 5 questions to complete.

You have completed

questions

question

Your score is

Correct

Wrong

Partial-Credit

You have not finished your quiz. If you leave this page, your progress will be lost.

Correct Answer

You Selected

Not Attempted

Final Score on Quiz

Attempted Questions Correct

Attempted Questions Wrong

Questions Not Attempted

Total Questions on Quiz

Question Details

Results

Date

Score

Time allowed

minutes

seconds

Time used

Answer Choice(s) Selected

Question Text

All doneNeed more practice!Keep trying!Not bad!Good work!Perfect!

July 23, 2012

Altruistic trees!

It turns out that trees not only communicate through fungal networks in their roots, they also pass nutrients around from tree to tree, even between species!

The fungi (many species) grow in contact with the roots of the tree, enjoying the steady source of carbohydrates that the tree has produced, and in exchange giving the tree advantages such as an increased surface area to absorb water, an ability to absorb some minerals like Phosphorus and Nitrogen, and more. Some species of fungus actually attract springtails (tiny insects) in order to kill them and absorb nitrogen from them. One study found that Eastern White Pines can get as much as 25% of their nitrogen from springtails (courtesy of these fungi).

Once nutrients and water are in the fungal network they can be transported around the forest underground. Carbohydrates, nitrogen, water, etc. gathered at one tree can end up above ground in another tree many yards away.

In this way the older and larger trees – Mother Trees – can support the growth of many smaller trees around them, and help young trees get established. Not that any conscious decision-making is involved, but it shows that the tree’s “experiences” are a lot richer than we thought. Amazing stuff, and a whole new perspective on the forest.

There are links to the scientific papers through Suzanne Simard’s web page here: http://farpoint.forestry.ubc.ca/FP/search/Faculty_View.aspx?FAC_ID=3198

July 20, 2012

Quiz 41: More identification by feet

More examples of the variety of legs and feet – color and structure – that can be found among the small songbirds.

With thanks, again, to Brian E. Small for providing the beautiful photos. You can see lots more at his website.

Legs and feet of songbirds 2

Please wait while the activity loads. If this activity does not load, try refreshing your browser. Also, this page requires javascript. Please visit using a browser with javascript enabled.

If loading fails, click here to try again

Congratulations - you have completed Legs and feet of songbirds 2.

You scored %%SCORE%% out of %%TOTAL%%.

Your performance has been rated as %%RATING%%

Your answers are highlighted below.

Question 1

FlycatcherWood-WarblerSparrowVireoQuestion 1 Explanation:Black Phoebe - Very short legs and small delicate feet are typical of the flycatchers, which use their feet for little other than grasping a perch. All flycatchers have dark gray to black legs.

Question 2

Question 2

Wood-WarblerOrioleFlycatcherSparrowQuestion 2 Explanation:American Redstart - the slender legs and delicate toes are typical of wood-warblers. Leg color varies greatly between species of wood-warblers, shape is less variable, but American Redstart has relatively long legs for a warbler.

Question 3

Question 3

Wood-WarblerSparrowFlycatcherVireoQuestion 3 Explanation:Song Sparrow - Robust legs and large sturdy feet with obvious claws are typical of the sparrows, although smaller and lighter species such as Chipping Sparrow have legs and feet similar to warblers and other small birds. Most sparrows have pale flesh-colored legs, but some are dark gray.

Once you are finished, click the button below. Any items you have not completed will be marked incorrect.

Get Results

There are 3 questions to complete.

You have completed

questions

question

Your score is

Correct

Wrong

Partial-Credit

You have not finished your quiz. If you leave this page, your progress will be lost.

Correct Answer

You Selected

Not Attempted

Final Score on Quiz

Attempted Questions Correct

Attempted Questions Wrong

Questions Not Attempted

Total Questions on Quiz

Question Details

Results

Date

Score

Time allowed

minutes

seconds

Time used

Answer Choice(s) Selected

Question Text

All doneNeed more practice!Keep trying!Not bad!Good work!Perfect!

July 18, 2012

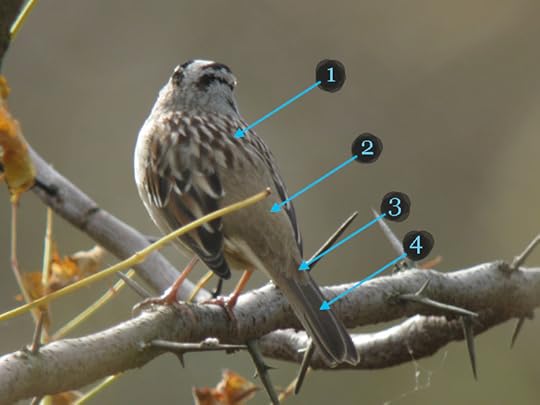

Quiz 40: Feather topography of the upperparts

More bird topography

Please wait while the activity loads. If this activity does not load, try refreshing your browser. Also, this page requires javascript. Please visit using a browser with javascript enabled.

If loading fails, click here to try again

Congratulations - you have completed More bird topography.

You scored %%SCORE%% out of %%TOTAL%%.

Your performance has been rated as %%RATING%%

Your answers are highlighted below.

Question 1The feathers labeled 1 are:scapularsnapemantlegreater covertsQuestion 2The feathers labeled 2 are:scapularsmantlerumpuppertail covertsQuestion 3The feathers labeled 3 are:tailuppertail covertsscapularsrumpQuestion 4The feathers labeled 4 are: rumptailmantleuppertail covertsQuestion 5The species is:White-crowned SparrowSong SparrowChipping SparrowBlack-headed Grosbeak

Once you are finished, click the button below. Any items you have not completed will be marked incorrect.

Get Results

There are 5 questions to complete.

You have completed

questions

question

Your score is

Correct

Wrong

Partial-Credit

You have not finished your quiz. If you leave this page, your progress will be lost.

Correct Answer

You Selected

Not Attempted

Final Score on Quiz

Attempted Questions Correct

Attempted Questions Wrong

Questions Not Attempted

Total Questions on Quiz

Question Details

Results

Date

Score

Time allowed

minutes

seconds

Time used

Answer Choice(s) Selected

Question Text

All doneNeed more practice!Keep trying!Not bad!Good work!Perfect!

July 17, 2012

Birds slow to react to predators because… the sun gets in their eyes

Song Sparrow avoiding the bright sun. Nogales, AZ. 30 Apr 2011. Photo copyright David Sibley.

An interesting study published recently found that cowbirds in bright sunlight were slower to detect predators and cowbirds in shade were quicker. The study concludes that the delay happens because the cowbirds are slightly disabled by the glare of the bright sun.

Could this explain why small birds are hard to find in bright sunny weather? Or why they are more active in the shade or on cloudy days? I had never really thought about it much, and just accepted the idea that it was heat-related – that birds stayed in the shade and under cover because that was more comfortable. But the absence of bird activity during the middle of the day can be explained as well or better by a simple predator-vigilance hypothesis. If it’s easier to see approaching danger and stay safe in the shade or on a cloudy day, and they have a choice, birds would be expected to avoid the bright sun glaring down.

References

Fernández-Juricic, E., Deisher, M., Stark, A. C. and Randolet, J. (2012), Predator Detection is Limited in Microhabitats with High Light Intensity: An Experiment with Brown-Headed Cowbirds. Ethology, 118: 341–350. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1439-0310.2012.02020.x/abstract

A heron ID quiz

Here is a photo of a white heron, taken by Constance Mier on the main shoreline of Biscayne Bay National Park, near Miami, Florida, on May 25, 2012.

You can see more of Constance’s photos at her webpage: http://cmierphotoandfitness.net/myphotos.html

White heron

Please wait while the activity loads. If this activity does not load, try refreshing your browser. Also, this page requires javascript. Please visit using a browser with javascript enabled.

If loading fails, click here to try again

Question 1What is the species of this all-white heron?Yellow-crowned Night HeronCattle EgretHint: Nope, bill is too thick, eye too big, and Cattle Egret should have black legsLittle Blue Heron (immature)Hint: No, bill is a little too thick, and Little Blue should have greenish-gray legs and bill, not yellow.Great EgretHint: Sorry, Great Egret would be much more slender, and have black legs.Great Blue (Great White) HeronHint: No, "Great White" Heron would be much more slender, and have drabber grayish legs and billSnowy Egret Hint: Nope, Snowy Egret is more slender and has black or greenish legs, dark billQuestion 1 Explanation:It's an albino Yellow-crowned Night Heron, identified by size and shape. The lack of melanin has left the bill and legs bright yellow, instead of the usual dark gray, but the eye color is not affected. The thick bill, large orange eye, moderately long and thick neck, and other clues all fit Yellow-crowned and no other heron.

There is 1 question to complete.

You have completed

questions

question

Your score is

Correct

Wrong

Partial-Credit

You have not finished your quiz. If you leave this page, your progress will be lost.

Correct Answer

You Selected

Not Attempted

Final Score on Quiz

Attempted Questions Correct

Attempted Questions Wrong

Questions Not Attempted

Total Questions on Quiz

Question Details

Results

Date

Score

Time allowed

minutes

seconds

Time used

Answer Choice(s) Selected

Question Text

All doneNeed more practice!Keep trying!Not bad!Good work!Perfect!

David Allen Sibley's Blog

- David Allen Sibley's profile

- 151 followers