David Allen Sibley's Blog, page 7

March 29, 2015

Red-winged Blackbirds showing off

This is the time of year when Red-winged Blackbirds are returning to marshes all over the continent, and the males are performing their showy displays to impress females and intimidate rivals. You might think the display simply involves fluffing up the body feathers and especially the red patches on the wings, but there is a lot more going on. I took these photos in May 2014 at Pelee Island, Ontario, and they work well to show the directional component of the display.

This is the time of year when Red-winged Blackbirds are returning to marshes all over the continent, and the males are performing their showy displays to impress females and intimidate rivals. You might think the display simply involves fluffing up the body feathers and especially the red patches on the wings, but there is a lot more going on. I took these photos in May 2014 at Pelee Island, Ontario, and they work well to show the directional component of the display.

When a male Red-winged Blackbird sings it fluffs up all of its feathers, spreads its wings slightly, lowers its head, and “hunches” its shoulders to show them off to full advantage. The best show is from the front of the bird.

Male Red-winged Blackbird singing and facing away, so that we see the bright red feathers of the shoulders “edge-on” and can see to their whitish base. photo © David Sibley

The Red-winged Blackbird from the front, the way this display is intended to be viewed, with the intense red of the shoulders set off against the very deep black shadows of the body and underwing. photo © David Sibley

Seen from behind or above, the display is still impressive but lacks the extremes of color that show from the front. The sheen of the back and wings is not really black, and because we are looking at the red wing coverts from behind we see down into the whitish bases of the raised feathers.

Viewed from the front, the red wing coverts have been pushed up to face us so that we see their flat red surface in full glory. The slightly spread wings, arched neck, and spread tail angled down all combine to create a solid and deep black that accentuates the brilliant red patches.

Knowing something like this is interesting on its own, but it can also help you find other birds. It’s a safe bet that the male has positioned himself to show off his best side, and looking in that direction may reveal the object of his attention.

March 23, 2015

A new quiz on backyard birds

Test your “partial cues” recognition skills. Each photo shows only part of a common North American backyard bird. (All photos © David Sibley.)

Backyard bird fragments

Please wait while the activity loads. If this activity does not load, try refreshing your browser. Also, this page requires javascript. Please visit using a browser with javascript enabled.

If loading fails, click here to try again

Question 1

AEuropean StarlingBBrown-headed CowbirdCRed-winged BlackbirdDCommon GrackleQuestion 1 Explanation:

AEuropean StarlingBBrown-headed CowbirdCRed-winged BlackbirdDCommon GrackleQuestion 1 Explanation:

Question 2

ARed-winged BlackbirdBFox SparrowCAmerican RobinDEastern TowheeQuestion 2 Explanation:

Question 3

Question 3

ANorthern CardinalBBrown-headed CowbirdCMourning DoveDAmerican RobinQuestion 3 Explanation:

Question 4

Question 4 ABrown-headed CowbirdBRed-winged BlackbirdCSong SparrowDHouse FinchQuestion 4 Explanation:

ABrown-headed CowbirdBRed-winged BlackbirdCSong SparrowDHouse FinchQuestion 4 Explanation:

There are 4 questions to complete.

You have completed

questions

question

Your score is

Correct

Wrong

Partial-Credit

You have not finished your quiz. If you leave this page, your progress will be lost.

Correct Answer

You Selected

Not Attempted

Final Score on Quiz

Attempted Questions Correct

Attempted Questions Wrong

Questions Not Attempted

Total Questions on Quiz

Question Details

Results

Date

Score

Hint

Time allowed

minutes

seconds

Time used

Answer Choice(s) Selected

Question Text

All doneNeed more practice! Go ahead, try again.Give it another try!Not bad!Good work!Perfect!

March 17, 2015

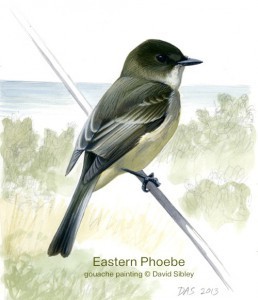

Why do phoebes pump their tails?

Lots of birds have a habit of pumping (or wagging) their tails. It’s mostly open-country birds like phoebes, wagtails and pipits, Palm Warbler, Spotted Sandpiper, and others. Many hypotheses have been suggested to explain why the birds do it, but nobody came up with an answer until Gregory Avellis in 2011.

He studied Black Phoebes in California, and tested four different hypotheses to see if tail pumping was related to:

balance – but tail pumping rate did not change depending on where the phoebes perched

territorial agression – playback of Black Phoebe song caused a territorial reaction but did not change the rate of tail pumping

foraging – tail pumping did not change significantly whether the birds were foraging or not

predators – playback of the calls of a potential predator – Cooper’s Hawk – caused tail pumping rate to triple

Avellis concludes that tail pumping is a signal meant to send a message to the predator. It tells the predator that the phoebe has seen it, and therefore the phoebe is not worth pursuing.

Avellis, G. F. 2011. Tail Pumping by the Black Phoebe. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 123: 766-771. abstract

December 6, 2014

Cackling-ish Geese

Cackling Goose is a rare fall migrant through Massachusetts and I usually see a couple of them each fall among the hundreds of Canada Geese around Concord. I look forward to the challenge of sorting through the flocks and picking these birds out, and once a candidate is located the identification has usually been straightforward – until 2014.

To begin the discussion and establish a baseline, here is a typical Cackling Goose with a typical Canada Goose:

A classic Richardson’s Cackling Goose (left) with a typical Canada Goose (right). The Cackling’s smaller size, relatively small bill and short neck, silvery gray back, and darker gray-brown breast with narrow white collar are all evident here. Belmont, MA Dec 2014. Photo copyright David Sibley.

In Massachusetts there are two distinct subspecies groups of Canada Goose: the breeding population (the “nuisance” geese of the suburbs) present year-round except during heavy snow cover, and northern migrants which arrive mostly in October. Learning to recognize these two forms helps with understanding the variation in Canada Goose.

Two subspecies of Canada Goose. Acton, MA, 7 November 2014. Photo copyright David Sibley.

In the photo above the larger goose on the right shows features of the mostly resident suburban Atlantic coast population (mixed subspecies moffitti and maxima) and the two birds on the left show features of migrants from the northern Quebec/Labrador breeding populations (subspecies canadensis or interior). The smaller size of the migrants can be obvious, as it is here, but there is plenty of overlap. Also note their dingier gray-brown breast color, and the fact that the far left bird is still in mostly juvenal plumage in November. Local residents molt out of juvenal plumage in September.

On November 5, 2014, I went out to browse the local geese, and I ran into this group:

Canada Goose (left) with three smaller Cackling-ish geese. Concord, MA, 5 Nov 2014. Photo copyright David Sibley.

One of the nice things about goose flocks is that geese maintain strong social relationships and birds tend to cluster in stable “subflocks”. Sometimes these are family groups, sometimes all adults, but I take it as a strong indication that the clustered birds share a common geographic (if not familial) origin. This can be very helpful for identification as it allows a sort of “average” impression of a whole group, which helps to cut through some of the extensive individual variation.

In this case the three smaller birds were staying together as a group, so I was trying to fit them all into the same species, either Cackling Goose or Canada Goose, not a mix.

Here is a close-up of two of the smaller geese.

Two Cackling-ish Geese. Concord, MA, 5 Nov 2014. Photo copyright David Sibley.

I can’t call these Cackling Geese; they are just a little too long-billed proportionally. On the other hand, I can’t call them Canada Geese either because even the right-hand bird is too small and dainty for any of the usual Canada Geese in Massachusetts.

Over the next few days I found at least three satisfactory Cackling Geese, but it became clear that there was a large group of at least 80 birds, all staying more or less together, that were a variable mix of intermediate sizes and colors.

Atlantic resident-type Canada Goose (front) and Richardson’s Cackling Goose (second from front), with a mix of intermediate birds beyond. Acton, MA, 7 Nov 2014. Photo copyright David Sibley.

Behind the Canada Goose and Cackling Goose in the foreground of the photo above, the cluster of geese on the right could be normal northern migrants, although they seem just a bit small for that. The four on the left, a family group, are distinctly smaller than any of the usual Canada Geese in Massachusetts, and the darkest juvenile (second from left) is unusually dark.

Here are some other photos of confusing individuals and family groups in this flock seen over the next few days:

Two Cackling-ish geese. Concord, MA, 8 Nov 2014. Photo copyright David Sibley.

These two (adult male on the right and juvenile on the left) are part of a family group of 7 (also shown in the next photo) that were all confusingly close to Cackling Goose but not quite right. The adult male (on the right, above, and back center, below) had a relatively large body but short and stout bill. The adult female was longer-billed while the juveniles, although small-billed and small overall, had more Canada-like bill shape.

A whole family of Cackling-ish geese (back). Concord, MA, 8 Nov 2014. Photo copyright David Sibley.

Canada Goose (center foreground) and many variably Cackling-ish Geese. 8 Nov 2014, Concord, MA. Photo copyright David Sibley.

In the photo above, the alert bird at left center looks small and small-billed, outside the range of the typical Massachusetts Canada Geese. The other swimming birds to varying degrees show paler silvery back color, small size, and short necks suggesting Cackling, in contrast to the single typical Canada Goose in the foreground. The group out of focus at the back right is the same family group featured in the previous two photos.

A Cackling-ish Goose (second from back) surrounded by a variety of less Cackling-ish geese. Concord, MA, 9 Nov 2014. Photo copyright David Sibley.

During the week or so that this flock was around I found them on most days and spent hours studying them. I waffled between wanting to claim as many as 50 Cackling Geese (unheard of in the Atlantic states), or just calling them all Canadas. Officially I felt comfortable reporting at least three different Cackling Geese, but unofficially I couldn’t figure out what to do with the ten or twenty other birds that were “near-Cackling”, and those blended with a few dozen others that were slightly larger, and so on.

One obvious possibility is that these birds represent the smaller subspecies of Canada Goose – B. c. parvipes or Lesser Canada Goose. Conventional wisdom says this subspecies nests across northwestern Canada but recent genetic evidence refutes that, and suggests that small Canada Geese may occur only in Alaska (Leafloor et al, 2013), and in Alaska the situation is very murky. Given that, the chance of a whole flock of Lessers showing up in eastern Massachusetts is vanishingly small. And to claim a flock of Lessers in Massachusetts I would want them to be a more uniform and discrete flock of medium-size birds, unlike the mixed flock that I saw, which ranged from Cackling-size to Canada-size in one loosely-associated group.

I hesitate to suggest it, but I think the evidence points to the possibility of this being a mixed flock of hybrids and backcrosses. Hybridization between Cackling and Canada Goose has been documented on the western shore of Hudson Bay (Leafloor et al, 2013) and there’s no reason to think it’s limited to that area. Farther east Cackling and Canada Geese meet on the breeding grounds in northern Quebec, Baffin Island, and Greenland – all normal sources for Massachusetts geese.

I’ve seen the occasional confusing individual goose in the past, but never a large group like this. Maybe I’ve overlooked them, or maybe several small groups just happened to converge on Concord, but it’s possible that the large numbers I noticed this fall are a new phenomenon. With climate change there have been big shifts recently in the distribution and numbers of nesting geese in that region, which could lead to other changes.

This is all just a working hypothesis, based on lots of suppositions and with lots of unanswered questions. Regardless of the answers, it’s clear that identifying Cackling Goose is not as straightforward as I thought, and goose-watching will be more challenging and more interesting because of that.

References

Leafloor, J.O., J.A. Moore & K.T. Scribner. 2013. A hybrid zone between Canada Geese (Branta canadensis) and Cackling Geese (B. hutchinsii). Auk 130: 487-500. abstract

December 3, 2014

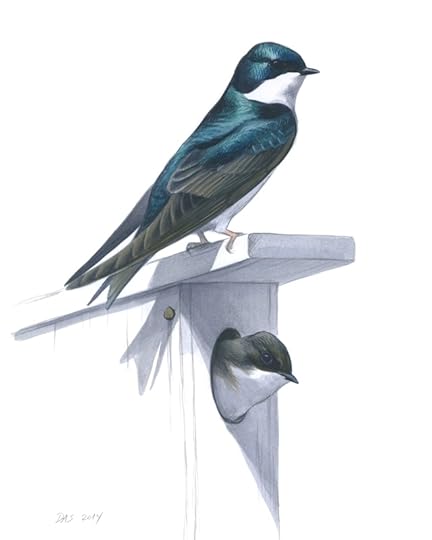

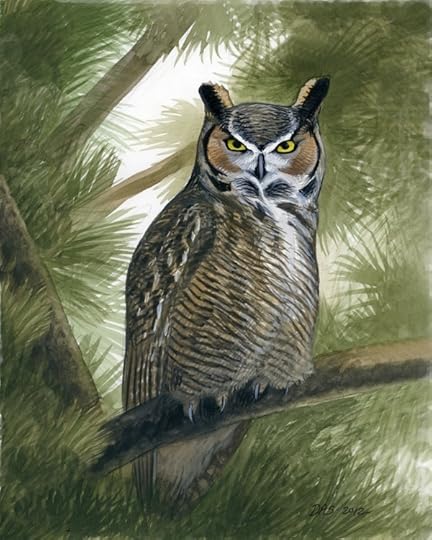

Four new prints to benefit conservation

Limited edition prints are now available of the four paintings shown below. These gouache paintings were completed between 2011 and 2014, and a portion of the proceeds from their sale will benefit the Bird Conservation efforts of Mass Audubon.

Be sure to check out the other conservation prints available here.

Male and female Tree Swallow

Great Horned Owl

Male Eastern Bluebird

Male Blackburnian Warbler, now available as a limited edition 9 x 11 print

Price: $45

When you click the “add to cart” button your “cart” will appear at the bottom of this page.

These 9 X 11″ limited edition giclee prints are made with archival ink and paper. Each edition is limited to 300 prints (with one Artist’s proof). Each print is signed and numbered, and comes with a certificate of authenticity.

Payment is through PayPal. If you are not already a PayPal member you can still pay with a credit card through the PayPal portal, which is easy and secure.

The shipping fee is $7 per shipment (not per print, higher outside the US); shipping is free on orders of three or more prints. Sales tax will be added for shipments to Massachusetts addresses.

Shipping is via USPS Priority Mail; please allow 7-10 days for packaging and shipping (contact me if you need faster delivery).

Other Prints for Sale

Gray Hawk from “The Wind Masters”

Snowy Owl

Northern Saw-whet Owl

Avocets and Semipalmated Sandpiper

The extremely variable American Pipit

I have been noticing variation in American Pipit for many years, and last month I had the opportunity to photograph a small flock. The photos here are of three randomly selected individuals in that flock, all taken within a few minutes on October 27, 2014 in Acton, MA.

The differences in color are striking: compare the color of the underparts (and contrast between flanks and back), the boldness of streaking on the breast, and the pattern on the face.

Bird A

Bird B

Bird C

Are these three different subspecies?

According to the descriptions of accepted subspecies (e.g. in Pyle 1997) I might identify bird B, the most heavily streaked, as eastern rubescens, and bird A, paler, as western pacificus. For bird C, the most richly-colored with sparse streaks, I could at least consider the possibility of montane alticola, although that subspecies should be paler. When I’ve studied pipits in California and Texas in the past that’s just how I’ve handled the variation. The problem is that in Massachusetts, unlike western states, only rubescens is expected based on range, and any of the others should be extremely rare. I know from observations over the last few years that this range of plumage variation is typical of every flock I study, and I doubt that Massachusetts is regularly getting mixed flocks that include pipits from across the continent.

Are they different ages or sexes?

Pyle (1997) mentions only molt limits and relative wear as a means of ageing, and only measurements as a means of sexing. He does suggest that females average heavier streaking than males (in breeding plumage). If that is true then it’s possible that bird B is a female and bird A is a male, but that’s just an idea that needs testing, and it doesn’t explain the differences in overall color or face pattern.

Is this just individual variation?

That’s the only answer left, and maybe it’s the right one. I resist it, though, partly because it calls the described subspecies into question, and partly because this is so much more variation than I see in other species. Think about Savannah Sparrow or Horned Lark, two other small ground-dwelling songbirds, in which tiny differences in overall color and pattern (much smaller than are shown by these three pipits) are consistent across large regions and lead to the naming of multiple subspecies.

If this is just individual variation, and American Pipit is the most variably-colored songbird on the continent, that leads to lots of other questions. And that’s what makes birding so endlessly fun and challenging.

November 23, 2014

A hawk in pigeon’s clothing

I saw a Cooper’s Hawk catch a Rock Pigeon a few days ago. By itself that experience is noteworthy – a Rock Pigeon is a big bird for a Cooper’s Hawk to handle – but more remarkable was the way the attack unfolded.

Cooper’s Hawk, original acrylic painting copyright David Sibley

I was just finishing a birding walk at a local farm. Ahead of me was a small field, recently plowed, where twenty or so Rock Pigeons were foraging on the ground. Another bird was about ten feet up and flying across the field toward the flock. I didn’t give it much thought. It was just another pigeon making the sort of relaxed, floating approach that pigeons do – or so I thought. Except that when this “pigeon” got within about five feet of the pigeons on the ground it suddenly transformed into a Cooper’s Hawk!

The pigeons all burst into flight, but much too late. The hawk was already among them and knocked one out of the air in a cloud of feathers.

I was stunned. It’s always shocking to witness a life-and-death drama like that, but a few seconds earlier I was simply seeing a pigeon flying in to join the flock when suddenly everything changed. And I wondered: How could I (and, more amazingly, a whole flock of pigeons) misidentify a Cooper’s Hawk like that? The hawk was in plain view, flying over an open field. Admittedly I did not give it much attention in that first glance, but there was nothing that drew my attention. It “registered” as a pigeon, which made sense for a bird coasting across the field. The pigeons must have seen it the same way, because normally they would not just sit on the ground and allow a Cooper’s Hawk to fly into their midst.

I considered the possibility that this was just a very lucky Cooper’s Hawk taking advantage of an opportunity with a flock of pigeons that either didn’t see it or didn’t think it was a threat. But I can’t imagine a whole flock of pigeons not seeing this bird approaching, nor letting it get that close under any circumstances.

I think the most plausible explanation is that the pigeons saw the bird but didn’t recognize it as a hawk (the same thing that happened to me), and that this was due to some deliberate mimicry by the Cooper’s Hawk, a brilliant bit of acting.

Predators rely on surprise, so if there is any way they can camouflage or “disguise” themselves and sneak up on their prey, it makes sense that they would take advantage of that. The resemblance of Zone-tailed Hawk to Turkey Vulture is often cited as an example of this aggressive mimicry. Potential prey species don’t react to the common and benign presence of Turkey Vultures overhead, and a Zone-tailed Hawk can hide among the vultures and drop onto unsuspecting prey.

Zone-tailed Hawks are born looking like Turkey Vultures, and they take advantage of it. I believe this Cooper’s Hawk was doing something more deliberate and active, transforming its wingbeats and flight actions to mimic another bird.

I’ve seen raptors mimic the flight style of other species before. Several times at Cape May, New Jersey I saw Merlins adopt the undulating flight style of a Northern Flicker, or the irregular flicking wingbeats of a Mourning Dove. It was only for a second or two and always when they were low and actively hunting.

This behavior is so infrequent, and so brief, that I suspect it will be very hard to confirm that it is deliberate aggressive mimicry, but I believe that all of these predators are trying to disguise themselves in order to sneak up on their prey.

September 18, 2014

Print to support shorebird habitat preservation

My newest print to benefit conservation efforts is this 2014 gouache painting of a Semipalmated Sandpiper with American Avocets (more info about my gouache technique here). This is a common scene in the Mississippi River Delta region, where catfish ponds and other managed wetlands create habitat for large numbers of American Avocets, migrating Semipalmated Sandpipers, and many other species.

A portion of the sale of each print will be donated to help fund the preservation and management of shorebird habitat. Delta Wind Birds is doing this work, partnering with private landowners in the Lower Mississippi River Basin to provide quality stopover habitat for migrating shorebirds along the Mississippi Flyway.

Price: $45

When you click the “add to cart” button your “cart” will appear at the bottom of this page.

This 9 X 13″ limited edition giclee print is made with archival ink and paper. The edition is limited to 300 prints (with one Artist’s proof). Each print is signed and numbered, and comes with a certificate of authenticity.

Payment is through PayPal. If you are not already a PayPal member you can still pay with a credit card through the PayPal portal, which is easy and secure.

The shipping fee is $7 per shipment (not per print, higher outside the US); shipping is free on orders of three or more prints. Sales tax will be added for shipments to Massachusetts addresses.

Shipping is via USPS Priority Mail; please allow up to 3 weeks for packaging and shipping (contact me if you need faster delivery).

Other Prints for Sale

Gray Hawk from “The Wind Masters”

Snowy Owl

Northern Saw-whet Owl

Print to Benefit Delta Wind Birds

My newest print to benefit conservation efforts is this 2014 gouache painting of a Semipalmated Sandpiper with American Avocets (more info about my gouache technique here). This is a common scene in the Mississippi River Delta region, where catfish ponds and other managed wetlands create habitat for large numbers of American Avocets, migrating Semipalmated Sandpipers, and many other species.

A portion of the sale of each print will be donated to help fund the work of Delta Wind Birds, which partners with private landowners in the Lower Mississippi River Basin to provide quality stopover habitat for migrating shorebirds along the Mississippi Flyway.

This painting of American Avocets and Semipalmated Sandpiper was done specifically for Delta Wind Birds, and sales of the 9 X 13 inch print will benefit their conservation work.

Price: $45

When you click the “add to cart” button your “cart” will appear at the bottom of this page.

This 9 X 13″ limited edition giclee print is made with archival ink and paper. The edition is limited to 300 prints (with one Artist’s proof). Each print is signed and numbered, and comes with a certificate of authenticity.

Payment is through PayPal. If you are not already a PayPal member you can still pay with a credit card through the PayPal portal, which is easy and secure.

The shipping fee is $7 per shipment (not per print, higher outside the US); shipping is free on orders of three or more prints. Sales tax will be added for shipments to Massachusetts addresses.

Shipping is via USPS Priority Mail; please allow up to 3 weeks for packaging and shipping (contact me if you need faster delivery).

Other Prints for Sale

Gray Hawk from “The Wind Masters”

Snowy Owl

Northern Saw-whet Owl

February 21, 2014

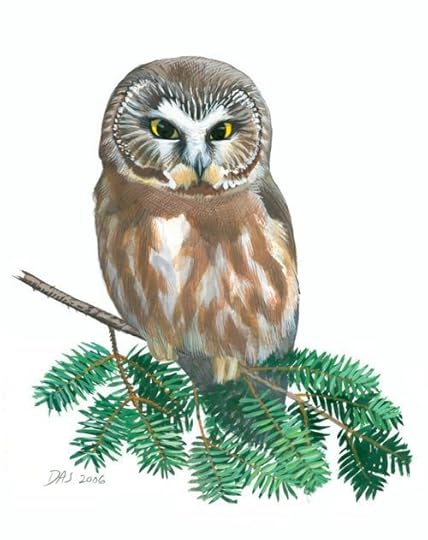

Saw-whet Owl print to benefit research

I have made prints of this gouache painting of a Northern Saw-whet Owl from 2006 (more info about my gouache technique here). This painting also appeared in a weekly newspaper column “Sibley on Birds”, and the original was auctioned to benefit the Ned Smith Center for Nature and Art.

A portion of the sale of each print will be donated to help fund the work of Project Owlnet, which facilitates communication and cooperation among hundreds of owl-migration researchers in North America, in particular studying the amazing migrations of Northern Saw-whet Owls.

Price: $45

When you click the “add to cart” button your “cart” will appear at the bottom of this page.

This 9 X 11″ limited edition giclee print is made with archival ink and paper. The edition is limited to 300 prints (with one Artist’s proof). Each print is signed and numbered, and comes with a certificate of authenticity.

Payment is through PayPal. If you are not already a PayPal member you can still pay with a credit card through the PayPal portal, which is easy and secure.

The shipping fee is $7 per shipment (not per print, higher outside the US); shipping is free on orders of three or more prints. Sales tax will be added for shipments to Massachusetts addresses.

Shipping is via USPS Priority Mail; please allow up to 3 weeks for packaging and shipping (contact me if you need faster delivery).

Other Prints for Sale

Gray Hawk from “The Wind Masters”

Snowy Owl

David Allen Sibley's Blog

- David Allen Sibley's profile

- 151 followers