John G. Messerly's Blog, page 51

March 12, 2020

Public Health Emergencies Reveal The Danger Of “To Each According To His Works”

(This essay originally appeared on March 9, 2020, at 3 Quarks Daily.

By Joseph Shieber, reprinted with permission.)

[Editor’s note. This expands on yesterday’s nascent post.]

The traditional assumption in the United States has been that each person is individually responsible for their own health care. In other words, the US has a system in which the wealthy are able to afford more or better care (with the understanding that more care does not always lead to better health outcomes!), and the poor are able to afford less or no care.

There is something intuitively appealing about the idea that you should be rewarded in relation to the work that you’ve done or the results that you’ve achieved. It’s the basis of the well-known children’s fable, “The Little Red Hen”, in which the hen tries to get her fellow barnyard animals (dog, goose, etc.) to help her sow the seeds, reap the wheat, grind the grain, and bake the bread. Since none of the other animals are willing to help, when the bread is done the hen eats it all herself. In fact, the fable is so intuitively plausible that folksy free-market hero Ronald Reagan — pre-Presidency — used it himself.

The idea behind “The Little Red Hen” is so intuitively appealing that it’s not just limited to free-market views. Even socialist thinkers from pre-Marxists like Ricardian socialists to later theorists like Lenin and Trotsky embraced the formula, “To each according to his works”, rather than Marx’s “To each according to his needs”.

Indeed, in a very useful paper, Luc Bovens and Adrien Lutz trace back the dual threads of “to each according to his works” and “to each according to his needs” to the New Testament. So, for example, in Romans 2:6, we see that God “will render to each one according to his works” (compare Matthew 16:27, 1 Corinthians 3:8).

In contrast, in Acts 4:35, we read that “There was not a needy person among them, for as many as were owners of lands or houses sold them and brought the proceeds of what was sold … and it was distributed to each as any had need” (compare Acts 2:45).

The deep textual roots of these two rival maxims suggest that each exerts a strong intuitive pull — though perhaps not equally strong to everyone.

Public health emergencies, however, reveal the fragility inherent in the motto of “to each according to his works” when it comes to health systems. Everyone’s health is interconnected, and that the ability of each individual to fight infection depends in part on everyone else’s having done their part.

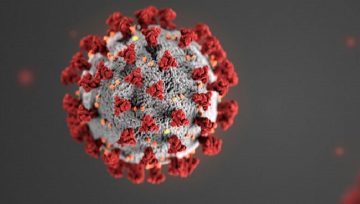

The most recent illustration of this comes from the threat of a pandemic of the newly-discovered COVID-19 virus. One of the effects of this threat is that it has led to strong questions about economic inequality and fairness of access to medical supplies and a potential vaccine.

For example, there was a widespread outcry when the current United States Secretary of Health and Human Services, Alex Azar, refused to guarantee that a vaccine for the COVID-19 virus would be affordable for all. Those comments sparked renewed attention to Mr. Azar’s own troubling history with questionable pharmaceutical price increases.

In the ten years from 2007 until his nomination to the HHS position in 2017 in which Mr. Azar worked for the drug manufacturer Eli Lilly, that company recorded a three-fold increase in the price of insulin. This is despite the fact that insulin, which is necessary for diabetes sufferers to manage their condition, has not been substantially improved since its first medical use almost a century ago.

This outcry, while understandable, actually misses the deeper point about why Mr. Azar’s actions should concern us. Even if someone resists the moral pull of “to each according to his needs” in favor of the competing maxim “to each according to his works”, the application of that maxim in the case of public health emergencies can lead to catastrophe for all.

Public health experts note that two of the most important weapons in the fight against pandemics are early detection of those infected and widespread vaccination. The “to each according to his works” model of healthcare removes both of those weapons from our arsenal.

When Mr. Azar, who is himself a lawyer and has no medical or public health expertise, fails to guarantee that any COVID-19 vaccine will be widely available, he weakens the effectiveness of vaccines as a weapon against the spread of infection. Vaccines work best when they’re distributed widely among at-risk populations.

Mr. Azar’s comments, in other words, are an indication that the Administration fails to grasp that—unlike Presidential pardons, perhaps—public health crises do not discriminate on the basis of celebrity or outsize wealth. Rather, the health of each one of us depends on all of us doing our part.

The “to each according to his works” model also threatens the other weapon against pandemic, early detection. If only those who can afford to get tested for COVID-19 report themselves to authorities, then we won’t know how widespread the disease in fact is.

To take an extreme example of this, the Miami Herald recently reported on Osmel Martinez Azcue, who sought a test for COVID-19 after returning from a work trip to China and experiencing flu-like symptoms. Although Azcue was simply acting in the way recommended by the Centers for Disease Control to be in the best interests of public health, he now faces thousands of dollars of medical bills from his insurance company, the hospital where he sought testing for the virus, and the individual doctors who treated him.

Unfortunately, these troubling examples seem themselves to be systematic of wider trends that do not inspire confidence in the ability of the United States to deal with the growing threat of COVID-19.

Profit-seeking is already causing obstacles to efforts to combat the public health risk posed by COVID-19. Stockpiling and price-hikes are making it difficult for medical personnel to acquire the masks and protective gear they need to stop spreading infection further.

Although the United States has lost valuable time in planning for this impending health care crisis while it was still contained in China, it is not too late to take steps to blunt the impact of the infection. In order to do so, however, the Administration must appreciate that pandemics do not distinguish on the basis of immigration status, ethnicity, or income. To fight COVID-19 effectively, we must begin by appreciating that we’re all in this together.

March 11, 2020

Coronavirus: We Are All Interconnected

Vox did its usual excellent job of reporting and analysis in the above video about the origins of the coronavirus in China. Now that the WHO officially declared the virus a pandemic—and since I live in Seattle, one of the epicenters of the virus—here are a few philosophical lessons that we might relearn.

I know it’s simplistic, but a major lesson is that we are really “all in this together.” I know this cliché is trite but it still points to an important truth. If you watch the video above you will find that, because there’s a market for consuming exotic animal meat among the wealthy, we’re all threatened with a pandemic. Halfway around the world, someone had a taste for exotic animals and thus you might die from a virus. Talk about the butterfly effect!

Yes, there is a sense in which we live together on spaceship earth! I don’t mean to deny the competitive struggle for existence that characterizes both our evolutionary history and the world today. When others are buying all the groceries in the stores we may have to modify our own behavior.

But the solution to this example of a prisoner’s dilemma is to recognize that we all do better and none of us do worse when we all cooperate. We aren’t always in zero-sum games, often we are in non-zero sum games. (Non-zero sum games describe situations where both parties involved in an interaction can gain something. Zero-sum games are when one party’s gain is the other party’s loss, that is, the sum is zero.)

The other lesson is how much we depend on each other. When people get sick they clamor for help from health-care workers—acting as if their lives depend on it! Where would any of us be without the doctors, nurses, pharmacists, researchers and all the others trying to keep us healthy? You may think that you are an independent individual. But you are not. Your life depends now, as it did in the past and will so in the future, on others. This should humble us all.

March 10, 2020

Trump is the American Nero

[image error][image error]

Given our current political climate, I realize that I took a relatively stable political system for granted most of my life. While the American government has always been characterized by corruption and immorality, I never feared it as I do now. Our government is becoming what can only be described by words like autocracy, totalitarianism, authoritarianism, fascism. As a further warning for what I’ve been writing about for the past few years, I want to draw my readers’ attention to two recent articles.

The first is long and complex but it is the single best essay on the danger of the Trump regime. I won’t summarize it except to say that it highlights, among other things, how the good, qualified, patriotic people are being expunged and coerced from government and being replaced by sycophants, grifters, degenerates, fanatics, and ideologues. The article, written by George Packer, appeared recently in the Atlantic and can be found below.

The second article is, “Former Bush White House lawyer Richard Painter: ‘Trump will grab as much power as he possibly can’: Former GOP ethics lawyer Richard Painter says Trump is the “American Nero,” and democracy is in extreme danger” by CHAUNCEY DEVEGA. Here is a brief summary.

Devega sets the stage for his interview with Richard Painter like this,

Trump and his regime have ushered in an Orwellian reality where truth itself is under siege, fully mated with a kakistocracy and plutocracy. The federal judiciary has been filled with Trump’s unqualified sycophants. Trump and Attorney General William Barr make threats against judges who do not do their bidding. Career government employees and other experts have been purged and replaced with unqualified

Trump loyalists.

…

Republicans have effectively declared Trump a king or emperor by “exonerating” him in an impeachment show trial in the U.S. Senate. Right-wing Christian nationalists view him as a godlike figure, the “Chosen One.”

Are there any limits left on Donald Trump’s assault on the rule of law and democracy? Could Trump order his political “enemies,” such as leaders of the Democratic Party, arrested and sent to prison? After the impeachment show trial, is Trump now the de facto king of America? …

In an effort to answer these questions and other Devega spoke with Painter, who was White House chief ethics counsel under George W. Bush. He is now a frequent political commentator and analyst, a professor of corporate law at the University of Minnesota, host of “The Politics Podcast With Richard Painter, and author of several books, including:

[image error] Getting the Government America Deserves: How Ethics Reform Can Make a Difference[image error],

and his new book, co-authored with Peter Golenbock, is

American Nero: The History of the Destruction of the Rule of Law, and Why Trump Is the Worst Offender [image error]

You can read the conversation between Devega and Painter at the above link but I’d summarize Painter’s responses by saying that he is very worried. For example, in answer to Devega’s question about Republicans agreeing with Alan Dershowitz arguing that Donald Trump is a king, that Trump’s personal interests are the country’s interests if he says they are, and therefore, Donald Trump cannot break the law, Painter’s response is chilling:

This is the great risk to our republic, and indeed this is what happened to the Roman Republic. The senators were elected by the rich people — but they were elected. They were senators and they had considerable power. And then, as the Roman Empire grew, they granted more power to the consuls. A republic transformed itself over about 150 to 200 years into a dictatorship or empire, where the leader had absolute power. Nobody stopped it. This is a lesson in how over time a republic, such as America, can be turned into a dictatorship.

Of course, a second example was the Weimar Republic in Germany, where over about 15 years a republic was turned into a dictatorship. In a matter of months after Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor, he consolidated executive power very quickly under Article 48 of the German constitution, which said the president and the chancellor could do anything they want if there’s an emergency. And then of course all a leader needed to do was declare an emergency and then it’s game over. Peter Golenbock and I wrote “America Nero” precisely because we don’t want there to be a third example of a republic becoming a dictatorship. The United States will become a dictatorship if we keep going along this path with Donald Trump.

And Painter’s answers to questions about Trump’s threats against the free press, free speech, private citizens, his threat to remain in office and punish his political opponents, the possibility of his declaring his opposition illegal, imprisoning opponents, and shutting down media critical of him, are equally disturbing. I urge you to read the entire article.

For more on a related topic, I urge my audience to read Devega’s “Trump’s authoritarian assault on democracy continues: What lies ahead? Fascism scholar Ruth Ben-Ghiat: If Trump wins again, America will be “ready for full-on authoritarian rule.”

____________________________________________________________________

Author’s Note. There has always been political evil and corruption. To live in a state with limited political corruption is the exception, not the rule. But is doesn’t imply ought in this case, and it is sad to see the degradation of a political system right before your eyes.

For those interested, the Corruption Perceptions Index published annually since 1995 by Transparency International, ranks countries “by their perceived levels of public level corruption, as determined by expert assessments and opinion surveys.” The CPI defines corruption as “the misuse of public power for private benefit.” Here are the top 10 countries according to there 2018 rankings:

1. Denmark

2. New Zealand

3. (tie) Finland, Sweden, Switzerland, Singapore

7. Norway

8. Netherlands

9. (tie) Canada, Luxembourg

Stay alert.

March 7, 2020

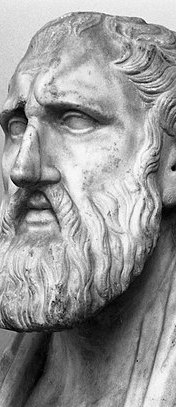

The Stoics on Happiness

Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoicism.

Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoicism.

[Previously, I promised to write about the Stoic view on living a good life. This is that post.]

I’ll begin by describing some Stoic exercises to give you a flavor of Stoicism, then I’ll provide a few bullet points of Stoicism, some summary remarks, a brief video, and links to my previous posts on Stoicism.

Part 1 – Stoic Exercises

Practice Misfortune – Practice poverty, eat less, sleep in a tent, etc. If you’re always comfortable you’ll fear that comfort will be taken away.

Turn the Obstacle Upside Down – If someone is unkind toward you, practice patience and understanding. If someone you love dies, practice fortitude.

All is Ephemeral – Remember our passions are ephemeral and our achievements are trivial.

The View from Above – Remember how small you are in the big scheme of things.

Meditate on Your Mortality – You could leave life today. Let that guide what you do and say.

Differentiate Between What You Can and Cannot Control – No amount of rage will change the weather or the traffic. But you can reject anger and rage.

Keep a Journal – Remind yourself and reflect upon what you’ve learned each day.

Practice Negative Visualization – If we prepare for the worst our inner peace will more likely remain when we encounter setbacks.

Love of Fate – Happiness isn’t getting what you want but wanting what you get. Treat all you encounter as something to be embraced.

(I am indebted to the authors of The Daily Stoic for the above list.)

Part 2 – The Bullet Points

a) Don’t Suppress Emotions, Control Them

To begin let me clear up the misconception that Stoicism advocates suppressing emotions. We instinctively react to situations with emotion but the Stoics teach us to reflect on the extent an emotion or passion is appropriate or justified. For example, we may quickly feel in love or angry with someone. But, after reflection, we may decide not to cultivate such feelings. In other words, we may (or may not) conclude that these feelings are appropriate.

For the Stoics, emotions or passions are ‘things which one undergoes’ and are to be contrasted with things one does. The Stoics aren’t arguing for apathy, but rather that you resist being subject to your passions—manipulated or moved by them. Instead, you should actively and positively control your reactions to things as they occur or will soon occur. Passions that particularly manipulate us are appetites and fear.

To reiterate, the Stoics don’t think that we should excise normal impulses or desires, only our excessive and irrational passions. These passionate emotions have a kind of momentum which subverts your reason. If, for instance, you are consumed with lust or greed you might act in ways that you would otherwise deem imprudent.

So the goal of the Stoic is to prevent the passions and emotions from controlling us and upset our peace of mind and equanimity. And this requires that we practice virtues such as wisdom, courage, justice, and moderation.

b) Control What You Can, Ignore What You Can’t Control, and Do Your Best

Stoics made a sharp (perhaps too sharp) distinction between things that are under our control and things that lay outside of it. The first category includes our own thoughts and attitudes, while the second one includes pretty much everything else. (For a funny rendition of this distinction, see this short bit by comedian Michael Connell.) The idea is that peace of mind comes from focusing on what we can control, rather than wasting emotional energy on what we cannot control.

However, this doesn’t imply that we neglect human affairs; remember, many prominent Stoics were politicians, generals, or emperors who tried to influence the world for the better while recognizing they couldn’t control the outcome of their efforts. And they accepted that things didn’t go their way.

c) Love for All

Indeed, Stoics thought of their philosophy as a philosophy of love, and they actively cultivated a concern not just for themselves and their family and friends, but for humanity at large, and even for nature itself. They were interested in improving humanity’s welfare.

d) Virtue is Happiness

The Stoics recognized that, among other things, we: (i) behave in order to advance our interests and goals (health, wealth, etc.); (ii) identify with other people’s interests; (iii) try to navigate the vicissitudes of life. These propensities are related to the four cardinal virtues of courage temperance, justice, and practical wisdom. Temperance and courage are required to pursue our goals, justice is a natural extension of our concern for an ever-increasing circle of people, and practical wisdom is what best allows us to deal with whatever happens. The most important good in life is a virtuous character.

Still, the Stoics readily admit that a preference for, say, wealth over poverty isn’t groundless even if such things aren’t always good for us. (For instance, wealth may make it easier to become addicted to harmful drugs.) Other things being equal, it is objectively preferable to have health rather than sickness.

Part 3 – Summary Remarks

The Stoics wrote about how we can become better, happier people capable of dealing with life’s problems. Consider that practicing misfortune makes you stronger in the face of adversity; reflecting on obstacles transforms problems into opportunities; not being controlled by passions leads to a better life; distinguishing between what you can and can’t control helps avoid distress; putting things in perspective makes for inner peace; and remembering how small you keep your ego in check.

So Stoicism is less a systematic philosophy than a series of tips for living a good life. It is a soothing ointment for the injury of living. As Epictetus said, “life is hard, brutal, punishing, narrow, and confining, a deadly business.” Stoicism means to help us flourish nonetheless by maintaining equanimity amidst the inevitable difficult situations that we will confront.

And here is a link to a short, recently-published essay:

“How an ancient philosopher helped me through one of the worst crises of my life”

Sources

Wikipedia – Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy – Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy –

Stoic Passions – How To Be A Stoic – The Daily Stoic – The School of Life – Reddit/Stoicism – “A Simplified Modern Approach to Stoicism” – Modern Stoicism

__________________________________________________________________________

[My previous posts on Stoicism. The first 3 listed have each been viewed over 50,000 times.]

March 5, 2020

Critiques of Reformed Epistemology

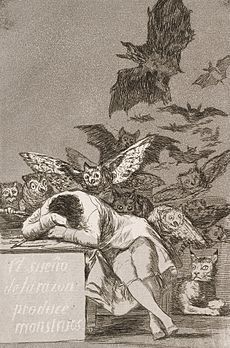

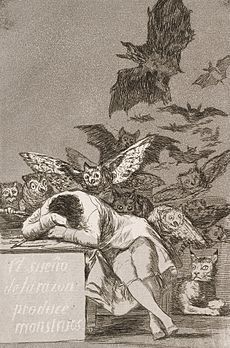

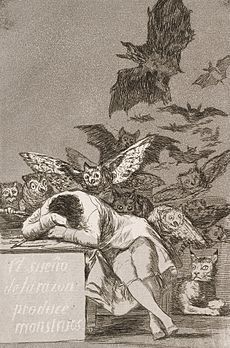

“The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters” by the Spanish painter, Francisco Goya

“The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters” by the Spanish painter, Francisco Goya

© Joshua H. Shrode – Reprinted with Permission

Reformed Epistemology … is indeed on the rise not just in Christianity, but apologists for Islam have started taking it up as well … (For more here’s a terrible paper written to commemorate the “legacy of Alvin Plantinga who reintroduced Christianity to the academy.” http://www.veritas.org/discovering-god-plantinga/ Personally, I wish the Academy had feigned a prior engagement.)

Now, remember that Plantinga claims that theists who argue that God is a properly basic belief are justified via their sensus divinitatis. It is this faculty that is defective in atheists and likely a result of sin. I kid you not. And this conclusion is, like everything it seems, self-justifying. If a being of unimaginable grandeur, power, grace, and justice can be justified “because I feel it’s true” then how is it different from claiming Flat Earthers are correct and justifying it via your sensus Flat-Earthitatis?

Plantinga tries to salvage his argument from ironically devolving into complete and total moral relativism by claiming that others with a sensus divinitatis, and especially other Christians, can still argue within that bubble of shared justified beliefs made true via direct revelation. So at best you get moral relativism, but between groups of theists.

That this is gobsmackingly stupid does nothing to either diminish his standing in Christian circles nor prevent it from, as you [Messerly] suggest, inoculating their worldview against foundational or empirical criticism. So maybe Christianity as a concept does owe much to Plantinga…but he has enabled so many zealots and fundamentalists to cloak their own ignorance in the patina of the academy.

My thoughts

For those interested, the Internet Encyclopedia devotes literally pages and pages to objections to reformed epistemology. It is a most thorough and readily accessible discussion.

For example, “There is a family of objections known as Great Pumpkin objections. These objections get their name from the Peanuts comic strip. In peanuts, the character Linus is a child who believes that each Halloween the Great Pumpkin will come to visit him at the pumpkin patch. What these objections have in common is that they claim that, if reformed epistemology is correct, then belief in God is no more rational than belief in the Great Pumpkin.”

And Wikipedia notes that “other common criticisms of Plantinga’s Reformed epistemology are that belief in God – like other sorts of widely debated and high-stakes beliefs – is “evidence-essential” rather than properly basic;[23] that plausible naturalistic explanations can be given for humans’ supposedly “natural” knowledge of God;[24] that it is arbitrary and arrogant for Christians to claim that their faith-beliefs are warranted and true (because vouched for by the Holy Spirit) while denying the validity of non-Christians’ religious experiences;[25] and that there are important possible “defeaters” of Christian belief that Plantinga fails to address (e.g., passages in the Bible that seem hard to reconcile with his assumption of divine authorship and inerrancy).

Finally, I’m well aware that arguing about such matters convinces almost no one. Believers will still believe, and doubters will still doubt. I viciously attacked these arguments in my previous post, so there isn’t much more to say. But I do worry when beliefs lack evidential justification. As W.K. Clifford argued long ago: it is immoral to believe things without sufficient evidence. Why? Because your beliefs affect others.

Critique of Reformed Epistemology

“The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters” by the Spanish painter, Francisco Goya

“The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters” by the Spanish painter, Francisco Goya

[In my previous post, I made my disdain for reformed epistemology clear. Apparently, a reader agrees. Here are Joshua Shrode’s comments, slightly edited, followed by a few final thoughts of my own.]

Reformed Epistemology … is indeed on the rise not just in Christianity, but apologists for Islam have started taking it up as well … (For more here’s a terrible paper written to commemorate the “legacy of Alvin Plantinga who reintroduced Christianity to the academy.” http://www.veritas.org/discovering-god-plantinga/ Personally, I wish the Academy had feigned a prior engagement.)

Now, remember that Plantinga claims that theists who argue that God is a properly basic belief are justified via their sensus divinitatis. It is this faculty that is defective in atheists and likely a result of sin. I kid you not. And this conclusion is, like everything it seems, self-justifying. If a being of unimaginable grandeur, power, grace, and justice can be justified “because I feel it’s true” then how is it different from claiming Flat Earthers are correct and justifying it via your sensus Flat-Earthitatis?

Plantinga tries to salvage his argument from ironically devolving into complete and total moral relativism by claiming that others with a sensus divinitatis, and especially other Christians, can still argue within that bubble of shared justified beliefs made true via direct revelation. So at best you get moral relativism, but between groups of theists.

That this is gobsmackingly stupid does nothing to either diminish his standing in Christian circles nor prevent it from, as you [Messerly] suggest, inoculating their worldview against foundational or empirical criticism. So maybe Christianity as a concept does owe much to Plantinga…but he has enabled so many zealots and fundamentalists to cloak their own ignorance in the patina of the academy.

My thoughts

For those interested, the Internet Encyclopedia devotes literally pages and pages to objections to reformed epistemology. It is a most thorough and readily accessible discussion.

For example, “There is a family of objections known as Great Pumpkin objections. These objections get their name from the Peanuts comic strip. In peanuts, the character Linus is a child who believes that each Halloween the Great Pumpkin will come to visit him at the pumpkin patch. What these objections have in common is that they claim that, if reformed epistemology is correct, then belief in God is no more rational than belief in the Great Pumpkin.”

And Wikipedia notes that “other common criticisms of Plantinga’s Reformed epistemology are that belief in God – like other sorts of widely debated and high-stakes beliefs – is “evidence-essential” rather than properly basic;[23] that plausible naturalistic explanations can be given for humans’ supposedly “natural” knowledge of God;[24] that it is arbitrary and arrogant for Christians to claim that their faith-beliefs are warranted and true (because vouched for by the Holy Spirit) while denying the validity of non-Christians’ religious experiences;[25] and that there are important possible “defeaters” of Christian belief that Plantinga fails to address (e.g., passages in the Bible that seem hard to reconcile with his assumption of divine authorship and inerrancy).

Finally, I’m well aware that arguing about such matters convinces almost no one. Believers will still believe, and doubters will still doubt. I viciously attacked these arguments in my previous post, so there isn’t much more to say. But I do worry when beliefs lack evidential justification. As W.K. Clifford argued long ago: it is immoral to believe things without sufficient evidence. Why? Because your beliefs affect others.

March 3, 2020

Faith and Properly Basic Beliefs

Triumph of Faith over Idolatry by Jean-Baptiste Théodon (1646–1713)

Triumph of Faith over Idolatry by Jean-Baptiste Théodon (1646–1713)

A reader asked my opinion of this quote: “The function of faith is to take a basic belief and cloak it in the aura of a properly basic belief.” ~ Anonymous

Faith

Here I take the reader to be referring to religious faith, although faith more generally is trust or belief in a person, thing, or concept. Furthermore, religious faith itself is a concept with various meanings. For instance, it might refer to believing in spite of or without evidence, having sufficient warrant for one’s beliefs, experiencing a personal relationship with some (perceived) God, or simply having concern about humanity. It is also thought to exist in degrees such that faith may develop, grow, and/or deepen.

For this discussion, I’ll consider religious faith, at least among Christians, as having belief or trust in a religious person (God, Jesus), thing (heaven, prayer), or concept (soul, grace).

Properly Basic Beliefs

Properly basic beliefs (also called basic, foundational, or core beliefs) are, under the epistemological view called foundationalism, the axioms of a belief system. Foundationalism holds that all justified beliefs are either basic—they don’t depend upon other beliefs—or non-basic—they do derive from one or more basic beliefs.

In the philosophy of religion, reformed epistemology is a school of thought concerning the nature of knowledge as it applies to religious beliefs. Central to Reformed epistemology is the proposition that belief in God is “properly basic” and not need to be inferred from other truths to be rationally warranted.

Belief in God as Properly Basic

The philosopher/theologian most associated with this view is Alvin Plantinga. Basing his position on the theology of John Calvin he argues that we possess a special faculty or divine sense for knowing that God exists without any argument or evidence. As Plantinga puts it:

Calvin’s claim, then, is that God has created us in such a way that we have a strong tendency or inclination toward belief in him. This tendency has been in part overlaid or suppressed by sin. Were it not for the existence of sin in the world, human beings would believe in God to the same degree and with the same natural spontaneity that we believe in the existence of other persons, an external world, or the past. This is the natural human condition; it is because of our presently unnatural sinful condition that many find belief in God difficult or absurd. The fact is, Calvin thinks, one who does not believe in God is in an epistemically substandard position—rather like a man who does not believe that his wife exists, or thinks she is likely a cleverly constructed robot and has no thoughts, feelings, or consciousness. Although this belief in God is partially suppressed, it is nonetheless universally present. (Plantinga and Wolterstorff. Faith and Rationality. University of Notre Dame Press, 1983, pg. 66.)

Plantinga concludes that “there is a kind of faculty or cognitive mechanism, what Calvin calls sensus divinitatis or a sense of divinity, which in a wide variety of circumstances produces in us beliefs about God.” Thus belief in God is on par with other basic beliefs. According to Plantinga, properly basic beliefs include:

I see a tree (known perceptually),

I am in pain (known introspectively),

I had breakfast this morning (known through memory), and

God exists (known through the sensus divinitatis).

This Is One Of The Most Desperate and Frightening Arguments in the History of Philosophy

It’s hard to believe that anyone would find this argument convincing unless they were already firmly committed to believing in, or are fervently motivated to believe in, a God. First of all, the lack of theistic belief around the world undercuts the argument from a divine sense. Why then so many non-believers? Furthermore, people’s ideas of the nature of Gods vary substantially. Why then so many different conceptions? Second, if the Gods are so properly basic then why are they so hidden? Why century after century do they remain so silent, so absent?

Let me also say that I’m glad I didn’t study these arguments extensively. Becoming immersed in nonsense often gives it the aura of respectability. But does anyone really believe that the non-spatial, non-temporal God of classical theism—omnipotent, omniscience, omnibenevolent, immutable, etc.—is as basic as the other beliefs listed above? I’m sure some people would say yes, but why then is there infinitely more disagreement about the existence and nature of Gods than about the existence of trees and breakfast? I think even the Gods would be amused by this argument.

Finally, reformed epistemology is quite pernicious. Once you decide your privately held beliefs must be true and needn’t be justified by evidence available to all then I fear for what might follow. Believing one has a monopoly on truth has often led to disaster.

Back To The Quote

“The function of faith is to take a basic belief

and cloak it in the aura of a properly basic belief.”

I believe the quote has it about right. Here’s my explanation of how I think this works (psychologically.) You fervently believe something because it seems true, it comforts you, you want to believe it, your group believes it, etc. Then you dig in and hold on tenaciously. But at some point, you realize your beliefs could be mistaken. Then you look for an intellectual defense to bolster your emotionally held beliefs, to defend them against outsiders. In your search, you happen to discover Christian reformed epistemology, finding that your beliefs are axiomatic or properly basic. No need for evidence, problem solved!

So the encounter with the intellectual argument augments one’s faith or belief. You begin with the belief, look for supporting reasons and then, not surprisingly, you find them. (For more see “Psychological Impediments to Good Thinking.”) Finding what seem to be good reasons further bolsters the faith. So faith makes you more receptive to viewing your beliefs as properly basic, and viewing your beliefs as properly basic bolsters your faith. They are a feedback loop. Faith is the water in which all this swims and in its absence, an argument that your beliefs are basic will never be convincing.

Psychological Explanations

Of course, you can provide a psychological explanation of mine or anyone’s beliefs. Perhaps my natural psychological tendencies lean toward being skeptical, questioning authority, wanting intellectual explanations, etc. This, in turn, was exacerbated by a scientific and philosophical education and other environmental factors. If all this is true then our beliefs simply reflect the combination of our nature and nurture. But this isn’t completely right either. Some ideas are true independent of people because they are more robust, more predictive, more consistent with the evidence, ie., more likely to be true. These are the well-confirmed ideas of modern science. All beliefs are not created equal.

Final Thoughts

In the end, I’m an evidentialist—the evidence is of primary importance to me regarding belief. But defenders of reformed epistemology say that they don’t need evidence for something properly basic because it’s axiomatic just like a = a, or triangles having 3 sides. But to me, this seems wildly implausible. And I shiver at the thought of those who defend controversially beliefs by essentially saying, “my belief in God is just like your belief that there is a table in front of you.” This is someone you cannot reason with and, as the Spanish painter, Francisco Goya so aptly put it. “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters.”

Francisco Goyo, “El sueño de la razón produce monstruos”

February 28, 2020

Trump: Corruption and Autocracy

Doug Mudar‘s latest post on his blog, The Weekly Sift, is titled “Accelerating Corruption and Autocracy.” It is the best summary and analysis of Trump’s malfeasance that I’ve found. And, as usual, Mudar’s work is painstakingly researched and his prose carefully and conscientiously crafted. Here are his introductory paragraphs,

Ever since he came down the escalator pledging to protect us from Mexican rapists, Donald Trump has shown corrupt and autocratic tendencies. Before long, he was leading chants about locking up his political opponents, welcoming Russian help in his campaign, encouraging his supporters to be violent, profiting off of campaign events, and saying that he would only accept the election results “if I win“.

Since taking office, he has funneled public money into his private businesses, continued building his wall without a Congressional appropriation, refused all demands for financial transparency and Congressional oversight, obstructed the Mueller investigation, assembled the most corrupt cabinet since Nixon, lied many times per day, and repeatedly expressed his envy of dictatorial regimes like North Korea and China.

But the authoritarian drift has definitely accelerated in the three weeks since every Senate Republican but Mitt Romney voted to let Donald Trump remain in office, despite proven abuses of power. As Atlantic’s Adam Serwer puts it, Trump’s acquittal marked “the end of the Trump administration, and the first day of the would-be Trump Regime.” Think about what we’ve seen since the Senate’s abdication of its constitutional role in controlling would-be autocrats.

1) A purge of “disloyal” officials. “The disloyalty here is not to the United States, but to the person of Donald Trump.” Examples include Lt. Colonel Alexander Vindman, his twin brother, Ambassador Bill Taylor, Ambassador Gordon Sondland, Ambassador Marie Yovanovich, Undersecretary of Defense John Rood, and Deputy National Security Adviser Victoria Coates.

Moreover, everyone in the FBI who had any connection to the original Russia investigation was purged long ago: James Comey, Andrew McCabe, Peter Strzok, Bruce Ohr, and Lisa Page, as well as the Justice Department leadership that refused Trump’s pressure to shut the investigation down: Jeff Sessions and Rod Rosenstein. The purges will likely continue throughout the administration.

2) Interference in the Stone trial. Roger Stone, Paul Manafort and Michael Flynn are the last loose ends in the obstruction of the Mueller investigation. Trump and Barr interfered with “the prosecutors’ sentencing recommendation (causing all four prosecutors to withdraw from the case rather than participate in political corruption of the processes of justice), attacked the judge, and attacked a juror.” Note that “Stone lied to Congress to protect Trump, and he threatened a witness who could expose that lie. A jury of his peers unanimously found that Stone’s guilt had been proved beyond a reasonable doubt.” The message to anyone who might testify against him is keep quiet and you’ll be taken care of.

3) Pardons for money. Trump’s pardons include Rod Blagojevich whose guilt is beyond doubt, “tax evader Paul Pogue, whose family has contributed over $200K to the Trump Victory Fund” and “criminal financier Michael Milken was pardoned after a request from billionaire Nelson Peltz, a Milken business associate who had just hosted a Trump fundraiser that netted the campaign $10 million.”

4) Pardons to maintain a corrupt network. Jeffrey Toobin explained the authoritarian nature of his other pardons:

Authoritarianism is usually associated with a punitive spirit—a leader who prosecutes and incarcerates his enemies. But there is another side to this leadership style. Authoritarians also dispense largesse, but they do it by their own whims, rather than pursuant to any system or legal rule. The point of authoritarianism is to concentrate power in the ruler, so the world knows that all actions, good and bad, harsh and generous, come from a single source. …

In this era of mass incarceration, many people deserve pardons and commutations, but this is not the way to go about it. All Trump has done is to prove that he can reward his friends and his friends’ friends.

Naturally, “all the beneficiaries of Trump’s mercy were convicted of the kinds of white-collar crimes Trump’s people might commit themselves.” That was exactly the point as Sarah Chayes explained in “This Is How Kleptocracies Work“

In return for this torrent of cash and favors and subservience, those at the top of kleptocratic networks owe something precious downwards. They owe their subordinates impunity from legal repercussions. That is the other half of the bargain, without which the whole system collapses.

That’s why moves like Trump’s have to be advertised. … Trump’s clemency came not at the end of his time in office, as is sometimes the case with such favors bestowed on cronies and swindlers, but well before that—indeed, ahead of an election in which he is running. The gesture was not a guilty half-secret, but a promise. It was meant to show that the guarantee of impunity for choice members of America’s corrupt networks is an ongoing principle.

5) Threats to the rule of law. The Justice Department under Bill Barr is no longer an independent agency but one dedicated to shielding Trump from the rule of law. Marcy Wheeler provides a great summary of the corruption. Here are a few highlights

The Stormy Daniels hush-money investigation sent Michael Cohen to prison, but all the follow-up evaporated after Barr took over at DoJ. Cohen claimed he worked under Trump’s instructions, and that the Trump Organization reimbursed his illegal campaign contribution. But those leads have been dropped.

SDNY seems to be slow-walking its investigation into Rudy Giuliani’s Ukraine shenanigans, now that a new US attorney has been appointed. The head of the neighboring Eastern District of New York has been put in charge of Ukraine-related investigations that SDNY had been pursuing.

A new US attorney in D.C. has led to a “review” of investigations there, including cases involving Michael Flynn and Erik Prince.

Barr assigned Connecticut US attorney John Durham to investigate the origins of the Trump/Russia investigation. Anyone tempted to investigate further Trump wrongdoing now knows that they risk becoming targets themselves.

Barr tried to stop the Ukraine whistleblower’s account from reaching Congress, and did not recuse himself even though he is mentioned in the complaint.

6) Tightening control of the intelligence services. When a February 13 briefing to House leaders of both parties “reported that Russia was repeating its 2016 interference in the 2020 election process, again for the purpose of electing Trump,” well, Trump wasn’t going to accept the intelligence. In response “He dismissed Maguire and replaced him with Richard Grenell, who has no intelligence background whatsoever. In a Washington Post column, retired Admiral William McRaven lamented Maguire’s fate: ‘in this administration, good men and women don’t last long’.” Or, as quoted by the a former director of the National Counterterrorism Center states:

Nothing in Grenell’s background suggests that he has the skill set or the experience to be an effective leader of the intelligence community. … His chief attribute seems to be that President Trump views him as unfailingly loyal.

As Mudar puts it: “As Ambassador to Germany … Grenell was noted for his identification with right-wing parties like Alternative for Germany. The German news magazine Der Spiegel … interviewed more than 30 sources including “numerous American and German diplomats, cabinet members, lawmakers, high-ranking officials, lobbyists and think tank experts.” Their conclusion?

Almost all of these sources paint an unflattering portrait of the ambassador, one remarkably similar to Donald Trump, the man who sent him to Berlin. A majority of them describe Grenell as a vain, narcissistic person who dishes out aggressively, but can barely handle criticism. … They also say Grenell knows little about Germany and Europe, that he ignores most of the dossiers his colleagues at the embassy write for him, and that his knowledge of the subject matter is superficial.

Furthermore, “Grenell used to work for a corrupt Moldavian oligarch, but didn’t register as a foreign agent.” This by itself should prevent you from getting a security clearance.

7) Summing up. Now you might think well, shouldn’t the President be in charge? Shouldn’t his subordinates follow his orders? No! “One problem — you might fairly say it was THE problem — the Founders were trying to solve when they wrote the Constitution was how to control executive power. Unfettered executive power quickly becomes dictatorship, and the rights of the People are then only as safe as the Dictator allows them to be.” That was the whole idea of separate but equal branches of government.

Since the founding of our country

executive power has also been controlled through the professionalization of the various departments, each of which balances political control by the President with its own inherent mission. So the Justice Department takes its policy from the President, but pursues the departmental mission of justice. The intelligence services try to find truth, the EPA protects the environment, the CDC defends public health, the military safeguards our country and its allies, the Federal Reserve balances economic growth against the threat of inflation, and so on. For the most part, presidents have known when to keep their hands off.

Until Trump … There is no truth other than the story Trump wants to tell. There is no mission other than what Trump wants done.

Students of authoritarianism have been warning us about his dangerous tendencies since he first began campaigning. But, as Rachel Maddow noted Friday night, we are well past the time for warnings. “The dark days are not ‘coming’,” she said. “The dark days are here.”

Brief Reflection

I wish that my many warnings weren’t apparently coming true. It’s possible that the Democrats will win the Presidency, Senate, and House. Maybe they will clean up corruption and start to play hardball like the Republicans have been doing to prevent the slide toward autocracy. But this will inevitably lead to even more violent civil war, as Republicans have made it clear that only naked power now matters. And once civil discourse is impotent it’s hard to see how things won’t become increasingly violent. I still fervently hope that I’m wrong. But if not I’d encourage my readers, if they have the means and opportunity, to consider leaving the country. (For more see “Best Countries to Live In“)

February 25, 2020

Is Philosophy Dangerous?

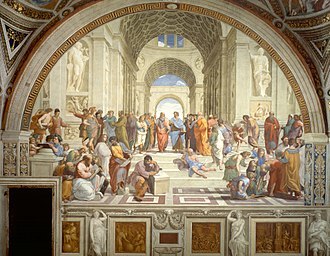

Clockwise from top left – Plato, Kant, Nietzsche, Averroes, Confucius, the Buddha

Clockwise from top left – Plato, Kant, Nietzsche, Averroes, Confucius, the Buddha

In my last post, I applauded a reader’s search for truth. I concluded that post as follows:

it’s easy to accept the first ideas you’re taught and be done with it. What’s hard is to keep searching and growing and changing, never anchoring as Kazantzakis put it. The search for truth is just so much nobler and humbler than simply affirming the first ideas you encountered.

I still agree with my conclusion but feel compelled to add a few caveats.

First, it’s natural for a professional philosopher to want others to follow in their footsteps or at least take an interest in what they are passionate about. It’s easy to recommend something that has provided you with so much intellectual stimulation, led to many rewarding friendships, and given your life, as far as is possible, a large part of its meaning.

But this supplies a reason to be (somewhat) skeptical of a philosopher’s advice. Perhaps they just want followers or are simply flattered that others share their passion. Or, more cynically, maybe they want your employment prospects to be as bleak as their own. Regardless of the philosopher’s motives, remember that philosophy isn’t for everyone. You may lack the interest or enthusiasm for it. Or it might not be where a field conducive to your particular talents. Regardless of your desires and aptitude, there is another reason not to embark on a philosophical quest—philosophy is dangerous.

Here’s what I mean. Serious students of philosophy must ask potentially disturbing questions. Does morality matter? Is love important? Is life progressing? Is it better that humanity exists rather than goes extinct? Is it better that I live rather than die? Does anything really matter at all? These questions aren’t merely academic; they pierce deep into the heart.

Honestly confronting these and other existential questions changes you—philosophizing has consequences. As Camus put it “beginning to think is beginning to be undermined.” After all, you may decide that life isn’t worth living.

Once the dam that holds back a world of ideas begins to crack, there is a good chance it will break altogether. And what then? Do you want to spend a lifetime trying to replace those first ideas you heard with (supposedly) truer ones? And even if they are truer, are they worth believing? Maybe it’s better to believe one of Plato’s noble lies?

So that’s my caveat. I have found philosophizing to be one of the great passions of my life. I literally have a truth fetish. I remember thinking when I was a teenager that if the answer to life, the universe, and everything was written on a piece of paper I would read it even if I knew that it might say life was pointless (or that the answer was 42!)

Still, philosophy is a dangerous pursuit which potentially will undermine your foundations and have nothing to replace them. You may end up with only a tragic optimism or hopeful nihilism to sustain you in the face of the tragic sense of life. That’s not much to hang your hat on.

You may even wish that you had never started to think at all. Every now and then I wonder if it would have been better to have remained relatively unconscious, comforted by those noble lies.

I’m not trying to dissuade you. Ultimately, I’m glad I outgrew my childhood beliefs and could never and would never go back to them. But philosophy is dangerous.

February 20, 2020

Searching for Truth

my book on Piaget.

my book on Piaget.

Bringuier – I wonder if what you attack in philosophy isn’t what is called metaphysics?

Piaget – Yes, of course …

Bringuier – But isn’t metaphysics, like the religious turn of mind or mysticism, a sign of one’s longing for unity? That’s what I meant about philosophy. One can’t turn up one’s nose at it too quickly, because the need exists. People have a need for unity.

Piaget – But, to me, the search for unity is much more substantial than the affirmation of unity; the need and the search, and the idea that one is working at it …

So anyone can say they have the truth, that they accept that Jesus is their savior or Mohammed is the last prophet. That’s easy. It seems like an insurance policy. But of course, it isn’t. Perhaps the gods reward those who use their minds, proportioning their assent to the evidence. Maybe the gods reject those who blindly accept things on faith alone, defaulting on the use of their reason. There is no sure bet.

So it’s easy to accept the first ideas you’re taught and be done with it. What’s hard and noble and humble is to keep searching and growing and changing. The search for truth is so much nobler than simply affirming the first ideas you encountered.