John G. Messerly's Blog, page 54

January 7, 2020

A Philosopher’s Lifelong Search for Meaning – Introduction

(Author’s note. I have added a brief introduction to this series of posts.)

Insignificant mortals, who are as leaves are,

and now flourish and grow warm with life,

and feed on what the ground gives,

but then again fade away and are dead.

~ Homer

Life is hard. It includes physical pain, mental anguish, loneliness, hatred, war, and death. But mere words cannot convey the quantity and intensity of human suffering. Consider that persons are starving, imprisoned, tortured, and suffering unimaginably as you read this; that our emotional, moral, physical, and intellectual lives are limited by our genes and environments; that our creative potential is wasted because of unfulfilling work, unjust incarceration, unimaginable poverty, and limited time; and that our loved ones suffer and die—as do we. Contemplate the horrors of history when life was often so insufferable that death was welcomed. What kind of life is this that nothingness is often preferable? There is, as Unamuno said, a “tragic sense of life.” This idea haunts the intellectually honest and emotionally sensitive individual. Life sometimes seems not worth the trouble.

Of course the above does not describe all of human life or history. There is love, friendship, knowledge, play, beauty, pleasure, creative work, and a thousand other things that make life, at least sometimes, worthwhile, and at other times pure bliss. There are parents caring for their children, people building homes, artists creating beauty, musicians making music, scientists accumulating knowledge, philosophers seeking meaning, and children playing games. There are mountains, oceans, trees, flowers, and blue skies; there is science, literature, and music; there is Darwin, Shakespeare, and Beethoven. Human achievement inspires us. Life sometimes seems too good for words.

Assuming that we are born without physical or mental maladies, or into bondage, famine, or war, in order to survive, we must be fed, clothed, and sheltered. Initially, we rely on others to meet these basic needs, but as we mature we must increasingly fulfill these needs on our own. The society in which we live may help us satisfy our basic needs, but many societies actively impede our attempt to live well. We often fail to meet our basic needs through no fault of our own.

But even if born healthy and into a relatively stable social and political environment, and even if all our basic needs are met, we still face pressing philosophical questions: What is real? What can we know? What should we do? What can we hope for? And, most importantly, what, if anything, is the meaning of life? This is the ultimate question of philosophy. Fortune may shine upon us but we and those we love will suffer and perish. And, if everything ultimately vanishes, then what, if anything, does it all mean? It is to this question we now turn.

January 5, 2020

Understanding Freedom: Freedom & Government – Part 1

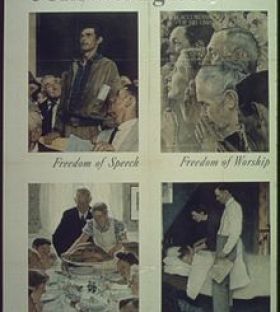

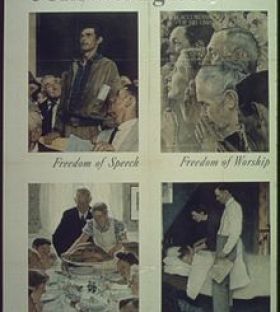

Four Freedoms, a series of paintings meant to describe the freedoms for which allied nations fought in World War II.

Four Freedoms, a series of paintings meant to describe the freedoms for which allied nations fought in World War II.

© Robert Orwell Hand – (Reprinted with Permission) https://understandingthings.net/2019/...

If freedom for all means that everyone is equally free, freedom and equality in a democratic society are, rather than competing with each other, two sides of the same coin.

Society organized in the interest of freedom and equality (ideally, if not so much in reality) is called democracy (from Greek, demos, lit., people; and kratos, lit., power). Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address summed it up as “government of the people, by the people and for the people,” updated (appropriately) by the Black Panther Party in the 1960s: “Power to the people!”

Throughout human history, the powerful have been relatively free to oppress the powerless. Which is to say that freedom has always been enjoyed by and, usually, the exclusive possession of the ruling classes. Human progress (defined in terms of freedom for all), therefore, has always consisted of restraining the power—which is to say, reducing the freedom—of rulers in the interest of empowering—that is, of freeing—the ruled. Progress has always taken the form of the long, hard road toward equalizing power relations among members of society, who cannot be equally free unless they are equally powerful (as Part I of this series explains).

Historically, government has been an instrument in the hands of the powerful to extract resources—that is, land and its natural resources, along with labor and the fruits of that labor—from the powerless to increase the wealth of the powerful, thereby maintaining and increasing their power. Only when government becomes a tool to restrain the owning class from exploiting the working class—who always represent the vast majority of “the people”—does progress toward freedom for all become a possibility.

And since freedom means the absence of external restraint, this governmental restraint of the powerful, of course, means the lessening of their (otherwise taken-for-granted and, therefore, invisible and unbounded) freedom. Therefore, freedom for all necessarily means a balancing out of freedom by means of redistributing power. This means, ideally, that rulers lose their power to rule and, by joining the ranks of the people, gain the power that is distributed among the people. (As rulers have so often resisted, by any means necessary, even minor and trivial reductions of their power, they have, in revolutionary times, sometimes lost not only their freedom/power but also their heads.)

Internationally speaking, the self-professed American goal has been to “spread freedom and democracy” to the rest of the world. Without democracy, freedom stops being a thing because it belongs un-self-consciously and only to the powerful (who cry out for “freedom!” only in relatively democratic societies in which their power has been, to even nominal degrees, limited to increase the freedom/power of the people).

The fact that the United States is a republic, that is, a state with a representative form of government, means that democracy is limited by constitutional law. This is necessary to protect the rights of individuals and minorities from the potential tyranny of the majority rule that (at least in part) defines democracy: when decisions must be made and democratic consensus is not achievable, majority rule cannot be allowed to violate the rights of individuals and minorities to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Rightly so. What is less clear regarding power in a democratic republic, however, is how to protect the rights of the majority from the tyranny of a powerful minority.

America’s founding fathers understood the threat of majority rule—i.e., of democracy (a word used in neither the Declaration nor the Constitution)—to one minority in particular, what James Madison called “the minority of the opulent” (by which he referred to the wealthy: the land-owners of the early American republic). Madison (the fourth U.S. President) has been called “the Father of the Constitution” due to the influence of his spoken and written words on the framing of the U.S. Constitution. The “permanent interests” of the country, represented by those who owned its land (the owning/ruling class of the time), Madison argued in 1787, “ought to be so constituted [that is, authorized by the U.S. Constitution] as to protect the minority of the opulent against the majority.” Madison and the other founders were, of course, class-conscious members of that “opulent” minority of land-owning aristocrats who led the colonies in the Revolutionary War against the British Empire.

As the late progressive historian, novelist, and essayist Gore Vidal pointed out, the two forces of which the founders were most frightened were, on one hand, the tyranny of a despotic ruler and, on the other, the rule of the masses. Which is to say that they were as frightened of democracy as they were of dictatorship. They coveted a republic after the fashion of the ancient Roman republic—which was anything but a democracy, even before Julius Caesar began turning it into an empire.

The American founders knew that democracy would always threaten the interests of the wealthy because the common people would naturally use whatever power they had to try to create a more equal distribution of the wealth produced by their own labor (if not, as the founders feared, to dispossess the owning class altogether). The birth and early growth of the United States corresponded to the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution, resulting in an ever-increasing number of Americans—formerly settlers, farmers and tradespeople—becoming part of the industrial “working class.”

The founders designed a constitution that allowed for some degree of political democracy while ignoring economic democracy, securing thereafter, for all intents and purposes, the (unspoken) socioeconomic distinction between the owning class and the working class in U.S. society.

The American mythology is, of course, that no class divisions exist in U.S. society. Rhetorical divisions of the working class into blue-collar and white-collar workers, and lower, lower-middle, middle, upper-middle and upper classes—with the owning/ruling class securely perched on the sky-highest beam of “the upper class”—serve to render invisible the obvious fact that the two-class system remains: the working class, which consists of employees who work for employers, and the owning class, who are the employers (the owners) of those employees. The over-riding power of the owning class is thereby obscured, rendering its freedom to exploit workers an invisible feature of the way things are. (The freedom of the owning class becomes visible, of course, in the form of its power, increasingly unhindered by the U.S. government, to impose harsh working conditions and low wages on workers.)

Initially, voters were required not only to be white males but also to be land-owners (landless white males being authorized to vote—on a state-by-state basis—from 1792 to 1856; African American males gained voting rights officially [though not, in practice, for long] in 1870; women in 1920; and American Indians in 1924). And initially, the U.S. Senate, unlike the U.S. House of Representatives, was not elected but appointed to office (the election of U.S. Senators resulting from the 17th Amendment to the Constitution in 1913).

These original constitutional provisions placed an obvious check on the power of the vast majority of Americans to influence their government and its policies. And power was gradually and partially redistributed to the people, as the history of voting rights clearly attests, only under pressure from the people, clearly indicating that the U.S. Constitution was always under review and always subject to amendment in the interest of democracy: of redistributing power to the people in the interest of freedom for all.

The result of constitutional protections of the “minority of the opulent,” writ large throughout American history, has naturally been that the owning class (that is, large land and business owners) has remained, ipso facto, the ruling class, whose members enjoy the power to (or power over those who) exercise governmental authority (including the necessary time and money to educate themselves for and dedicate themselves to it). Which, of course, they (with few exceptions) exercise in the interest of preserving and expanding the power, and corresponding wealth, of their own class.

The worldwide reality is that the powers that be—regardless of whether their rule takes the form of a dictatorship or a so-called “democracy”—will always view people-power/freedom for all as a threat. To read the writings of America’s founding fathers with understanding is to sense their internal struggle between, on one hand, their ideal of freedom for all and, on the other, their self-interest as aristocratic land-owners (and, for the most part, slave-owners). They had risked their lives to free themselves and their property (which, ironically, included those whom they wished to keep enslaved) from what they considered the oppressive power of the British Empire (which had already abolished the institution of chattel slavery), and they designed a constitution that would protect their interests in perpetuity. (This is not to demean the U.S. Constitution but, rather, to recognize it as—rather than a divine revelation—a human invention in need of further amendment in the interest of freedom for all, as the Bill of Rights makes clear was understood from very early on.)

Political democracy cannot exist without economic democracy because economic power is inseparable from political power. Those with economic power run the government because political power costs money. (The most obvious example, among many, is political campaigns, the cost of which typically makes politicians the servants of their corporate donors/masters.) If political democracy means, at least ideally, that political power is distributed among the citizens, who thus engage in self-government, then economic democracy can only mean that economic power is distributed among the workers, who thus engage in self-ownership. (And, of course, the vast majority of U.S. citizens are workers.)

Governmental protection (from exploitation by the owning class) and empowerment of workers (“the 99%”) is the general meaning of the term socialism (which is, of course, indicted as the arch-enemy of freedom by the powers that be). Socialism, in its original sense, calls for workers to retain control over the fruit of their own labor, instead of surrendering it to their employers/owners, whose intent is always to maximize the profits for themselves of “free enterprise.”

Today, “socialism” has come to refer to any government action, first, that regulates business activity to protect members of society (i.e., workers/consumers/citizens); and, second, that redistributes wealth from the owning class to the working class, primarily via a progressive taxation of wealth (i.e., the wealthier you are, the higher the tax rate on your income), redirecting that wealth into social programs that benefit all members of society. The primary examples of this kind of socialism in the U.S. government today are Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid, as well as (at least for the time being) public education, among other public services; it used to include public works programs that consisted of the government’s employing workers to construct and maintain infrastructure like roads and bridges, as well as the government’s providing public housing for the poor. (Public works programs have long since been considered too expensive to fund by the owning class and its tax-cutting, right-wing political representatives.)

Many owners view any kind of progressive taxation of their wealth in the interest of social welfare as theft, ignoring the fact that they (or their forbears) acquired, and that they maintain and expand, their wealth on the backs of taxpayers, who fund the kind of society that has made the ongoing and growing prosperity of the wealthy possible: taxes fund the education of their workers, the infrastructure that allows the transport of their goods and services, the police whose primary duty is to protect their private property, etc. The reality is that the owning class is forever redistributing the wealth that is produced by its workers to itself, while using the political influence its wealth buys from government officials to engineer all kinds of loopholes and waivers in the tax system to minimize, and often eliminate, its payment of taxes.

Nevertheless, while the redistribution of wealth from owners to workers via progressive taxation —far from being theft—is altogether fair and just, it falls short of the redistribution of power that socialism, in the sense of workers’ ownership of their own labor and its fruits, calls for: the organizing of power relations in such a way that owners and workers would be equals because they would be one and the same people.

So, then, a government “of the people, by the people, and for the people”—that is to say, a democratic, or people-powered, government—would not just protect workers (“the 99%”) from exploitation by their owners but would free workers from their owners. Which is to say that a thoroughly democratic government would empower workers with the ownership of their own labor and its fruits. This would seem to be the goal that lies at the end of the road of progress toward freedom for all.

Nevertheless, the counterargument that insists that this goal is both unrealistic and unrealizable is ever-present, having been securely instilled in the American consciousness. And that counterargument is made, of course, by the very powers that be that have arranged the way things are.

January 2, 2020

Understanding Freedom: Freedom & Power

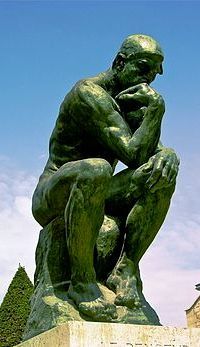

Four Freedoms, a series of paintings meant to describe the freedoms for which allied nations fought in World War II.

Four Freedoms, a series of paintings meant to describe the freedoms for which allied nations fought in World War II.

© Robert Orwell Hand – (Reprinted with Permission) https://understandingthings.net/2019/...

Americans like to say, “It’s a free country,” especially when someone expresses a desire to do something that might be frowned upon. The reality, however, is that freedom in America, or anywhere else, belongs only to those with the power to enjoy it.

When I was a college English composition professor, I sometimes assigned my students to write on the topic of freedom (arguably the supreme value in the hierarchy of values that we call “American”). We would begin with definitions, their most common: “being able to do whatever you want.” In that most were recent high-school graduates, their impatience with parental supervision made that definition especially understandable. And most Americans probably share that basic notion of freedom.

However, defining freedom as being able to do whatever misconstrues freedom as the presence of something, specifically, as an ability of some kind. Freedom is not, however, a human ability, nor is it the presence of anything at all. Freedom is, in fact, the absence of something, specifically, the absence of external restraints on a pre-existing ability. It may be the absence of parental supervision over what children are able to do, or, in the political and constitutional sense, the absence of governmental prohibitions of citizens’ ability, for example, to express dissent or to assemble in public. In other words, freedom means there is no one with recognized authority saying, “You can’t do that,” when you wish to do whatever it is you wish, and already have the ability, to do.

Another word for that ability to act according to your wishes is power.

So, rather than freedom being the ability to do whatever, freedom is being allowed to do whatever, assuming you already have the power to do it. The idea of freedom, then, also assumes the existence of a higher power that has the authority to either permit or prohibit whatever you have both the will and the power to do. If there were no higher powers—parental, governmental, or other—to potentially prohibit action, we would all naturally do, for better or for worse, whatever we had the will and the power to do, and the idea of freedom would be unnecessary and superfluous. But of course, the reality is that higher powers have always existed to thwart the lower, and lesser, powers—like yours and mine—that might otherwise threaten their monopoly on power. Which is why freedom became a thing in the first place.

Since, then, it is the absence of external restraints on your power to act, freedom assumes the presence of that power, removing whatever external force may otherwise restrain your power to do what you wish. Apart from the presence of power, then, freedom—the absence of external restraints—is useless, of no consequence, at best an empty slogan, a chimera that conjures up unrealizable hopes.

In short, you must have power for freedom to be relevant to your life.

So, for example, what use is freedom of speech if you lack the power of speech, or to otherwise communicate your thoughts and feelings? What use is freedom of thought if you lack the power to think. The totalitarian “Party” of George Orwell’s 1984 allowed all those outside the Party to have intellectual “freedom” only because it had already robbed them of intellect, by depriving them of education, even banning books as a means of self-education. Additionally, what use is freedom of choice if you lack the power to select among options—purchasing options, for instance, few or none of which you can afford? Ultimately, what use is any kind of freedom if you lack the power to ensure your probable future survival in the event of nuclear war or climate disaster?

Consequently, the experience of freedom is always the unrestrained exercise of power, that is, power unhindered by external forms of restraint. America is a “free country,” then, only for those with the power to experience America’s freedom. For those without at least viable access to power, “freedom” is a lie.

The powerful of the world (monarchs and masters and those who comprise “the ruling classes”) have always been free to act in their own interests, the only restraint being some competing force of relatively equal or greater power. In their given realms, rulers have always enjoyed the experience of freedom until they are overpowered and replaced by rivals, either from within their realms or from neighboring realms. And rather than freedom, the people under their rule experience the external restraints (military and economic and social) imposed on them by their rulers, so that their rulers can go on experiencing their own freedom to exercise their own power.

This freedom of rulers, however, isn’t typically called “freedom” because it isn’t a conscious thing at all; it is taken for granted if no external authority—no higher power—exists that can restrain the power of rulers. Their freedom is invisible, like the air we breathe, a matter of the way things are.

And the way things are has always been orchestrated by the powers that be.

Or maybe not. The earliest peoples of the world—organized in hunter-gatherer tribal societies—seem to have been characterized by a social egalitarianism that consisted more of power-sharing than of power-seeking, as much or more of cooperation than of competition; their primary external restraints were imposed on them by the natural world, which—by its threats of inclement weather, wild predators, and seasonal scarcity of food sources—limited their ability to survive on a daily basis. This is not to say that power was not exercised one over another but, rather, that power was not concentrated in the hands of a few; instead, power shifted from one to another according to situational contingencies that required a variety of abilities and skills.

Freedom could become a thing only after the emergence of social hierarchies, the result of the historical transition from hunter-gatherer societies to larger farming and herding societies and then to huge manufacturing societies, which concentrated power in the hands of a few, whose overruling power seemed necessary to maintain the increasingly complex structures and systems that provided for the survival of all. This development made survival more feasible for the people of the world, but it also made them the servants—more or less, the property—of the powerful.

It was only then that freedom could become a thing because those on the losing end of power relations could, and eventually would, somehow figure out that the way things are is not inevitable or irreversible—a matter, for example, of “the divine right of kings” or of “irresistible market forces”—but, instead, is the design of the (quite earthly and mortal) powers that be. The realization slowly dawned that power did not have to be the exclusive property of the few but could be divided among the many. And this distribution of power, to whatever degree it has been practiced, has been identified with the freedom to exercise it.

And once freedom became a thing, it could somehow eventually, at least in the human imagination, become the quintessential experience that constitutes human existence, defining human progress as progress toward the goal of freedom for all. This definition of human progress necessarily calls for the gradual lessening of the invisible, unspoken freedom—that is, the gradual reduction of the power—of the powers that be. Which is to say that only as restraints are imposed on the rulers of the world are restraints then lifted—if ever so gradually, in fits and starts—from the people of the world.

Freedom for all, then, must be the socio-economic-and-political meaning of equality: the evening out of power relations, the redistribution of socio-economic-and-political power among the people of the world.

Which is to say that freedom and equality are not—contrary to ideologies that seek to preserve the status quo of power relations—somehow opposed to one another, as if the more of one means, necessarily, the less of the other. (In the alleged sentiment of the early Virginia congressman John Randolph: “I am an aristocrat. I love liberty, I hate equality.”)

In fact, freedom without equality can only mean the ruthless oppression of the powerless by the powerful, the devastating and demoralizing exercise of whose power has simply been, at most times and places throughout human history, a matter of the way things are. Consequently, freedom and equality, in any kind of human terms that matter for everyday people, cannot exist except as two sides to the same coin.

Political “freedom” (Greek, eleutheria) emerged in ancient Greece during those on-and-off periods of “democracy” (or people-power: demos, lit., people; kratos, lit., power) in Athens from the 6th to the 4th centuries B.C.E. However, the birth of “freedom and democracy” was not, even ideally, a matter of freedom for all. In fact (as Hannah Arendt pointed out), Athenian “freedom” depended on slavery for its very existence because the primary obstacle to human freedom was understood to be necessity, specifically, the necessity of labor to secure one’s survival. The necessity of work was viewed as such a huge external restraint on a human being’s power that it made the “freedom” of any an impossibility without the slavery of many. Working to provide life’s necessities left no time for politics or philosophy or art or other pursuits that defined what it meant to be human in the Greek polis. Consequently, slaves were necessary to perform the productive labor that left men (though not women) free to conduct the affairs of state, and otherwise exercise the powers of their humanity. The necessity of female labor in childbirth was thought to exclude Greek women from the full possibilities of “freedom,” confining them, with few exceptions, to the private realm of household affairs.

Aristotle defined democracy as government by the poor—the vast majority of the people (Greek, demos) being poor—as opposed to oligarchy: government by the rich few. Yet even during the democratic periods of Athens, those who were most fully relieved of the necessity of labor by the larger number of their slaves and who could best afford a private education in rhetoric (originally, the political art of public speaking)—in short, the freest of the free—were the ones who exercised most of the power. These, of course, were the wealthiest citizens of Athens.

In the Western world (and as far as the labor of whites was concerned), slavery gradually and partially gave way to feudalism in the Middle Ages, masters becoming lords and slaves becoming serfs, virtually all governments being monarchies. The power of the lords was restrained primarily by the edicts of their kings, who often considered it their divine right to impose whatever their will might be on the nobility.

A limited freedom began to reemerge with the signing—under duress—of the Magna Carta (in 1215 C.E.), the primary purpose of which was to limit the power of King John over the barons of England, guaranteeing them certain forms of legal due process, thereby increasing their relative freedom from kingly oppression. Another kind of freedom was granted even the serfs in the form of “the commons”: land that was designated as public property, for the enjoyment and enhancement of all.

When democracy reemerged philosophically in Europe and then politically in America with its revolution, the idea of freedom for all began to be conceived as a God-given right, though the all still excluded non-whites and women. New, however, was—with the advent of the Industrial Revolution—the inclusion of workers, the necessity of labor somehow, at least theoretically, no longer a disqualifying factor in regard to their “freedom.” This inclusion of workers in the expanding circle of who qualified for freedom was necessitated by the Industrial Revolution, whose factories needed an ever-increasing supply of “free” labor and whose factory owners—via their influence over government policies regarding land and other natural resources—made sure that most alternative means of survival gradually became untenable and obsolete.

The end of the gradual economic transformation of masters (i.e., owners of people) into lords (i.e., owners of land) into employers (i.e., owners of companies/corporations) required the masses of people to willingly submit themselves to becoming employees, subject to the impersonalized and institutionalized working conditions of factories and, subsequently, other technology-driven enterprises. Workers had to be persuaded that they were freely choosing to do this in exchange for a wage. They were “free,” then, to work or not to work (in which case, to starve), and “free” to work for this, that or the other employer (all of whom exercised virtually limitless power over them in exchange for their strictly limited wages).

So (as progressive economist Richard Wolff points out), the economic transformation of slaves (who were the property of their masters) into serfs (who worked land that was the property of their lords) into employees (whose labor and its fruits, in exchange for a wage, are the property of their employers) is supposed to have completed the movement from slavery to freedom for all. In reality, however, calling the powerful “employers” rather than “masters” or “lords,” and calling the powerless “employees,” rather than “slaves” or “serfs,” doesn’t change the fundamental power relations between the powerful and the powerless, who continue to suffer the way things are as arranged by the powers that be.

In effect, the ancient Greek dependence of “freedom” on slavery has reemerged as the newest version of the way things are: if business owners are truly to experience freedom—now called “free enterprise”—a new form of slavery is required: what the owners call “free labor” has been called “wage slavery” by those who have continued to uphold and pursue the ideal of freedom for all.

Employment is called “wage slavery” because workers are required to surrender their labor and its fruits—which, for all intents and purposes, means their lives—to their owners. The terms “employer” and “employee” disguise the power relations between owning class and working-class: If the employer is the owner of the company and the employer of the employees who form the productive apparatus of the company, is he (or she) not also the owner of the workers?

Of course, this is the case only while workers are “on the job.” They go home as free men and women. But time spent “on the job” has always amounted to the vast majority of the waking hours of workers (even after labor unions forced owners to adopt the eight-hour workday). And workers are forced to do their jobs in exchange for a wage over which they have (especially in the absence of labor unions) little or no say, that is to say, no power. Well, not technically forced, of course, in that they are otherwise “free” to starve.

In the southern United States, chattel slavery continued for nearly a century—from the founding of the nation until the Civil War—because the “freedom” of the plantation owners to maintain their aristocratic status quo depended on it. And even with the abolition of slavery, the lords of the South engineered ways—most notably, the prison system, which was constitutionally authorized by the 14thAmendment to treat prisoners as slaves by requiring them to work without wages—to perpetuate slavery, by either falsely accusing, prosecuting and convicting African Americans of criminal offenses or inventing crimes (like “loitering”) for which to incarcerate them, on a widespread basis. (A common alternative, for those who were not imprisoned, was lynching.)

And poor southern whites—counterparts of the northern factory workers who were forced to sell their labor so cheaply—continued as virtual serfs, placated by the belief (fed them by their land-owning lords) that their whiteness granted them human dignity, despite their poverty, that black people necessarily lacked.

Every step of progress in the so-called “civilized world” toward the still unrealized goal of freedom for all has amounted to the forcible reduction of the invisible freedom of the powers that be, who rarely if ever voluntarily relinquish an ounce of their power. Their universal purpose has always been and, presumably, will always be, instead, to consolidate and expand their power (along with the wealth that power brings and that inevitably brings more power). In the words of Adam Smith (in The Wealth of Nations, 1776): “All for ourselves and nothing for other people, seems, in every age of the world, to have been the vile maxim of the masters of mankind.” As history shows, as long as the powerful few remain powerful, they will use their freedom to maintain and increase their power, allowing others only the relative freedom/power necessary to continue the process.

In the familiar words of the British political philosopher Lord Acton, “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” Power, on one hand, is necessary for people to satisfy their individual and collective needs and to gratify their individual and collective desires; on the other hand, when power is concentrated in the hands of a few, corruption is inevitable: the powerless many suffer at the hands and in the interests of the powerful few.

Accordingly, the more widely and broadly power is distributed, the less corrupting it will be. The invisible freedom of the powerful inevitably results, again and again, in the oppression of the powerless, regardless of whether or not the powerless are told that they are “free.” The power of the few, therefore, must be diffused, redistributed among the many, in the interest of freedom for all. And this, not to make the powerful few powerless but, instead, to allow them no more power than anyone else. Which is called equality.

(Next: Understanding and Freedom: Freedom and Government-Part 1)

December 31, 2019

A Philosopher’s Lifelong Search for Meaning – Table of Contents

(Author’s note. This is a table of contents for my posts last year about life and meaning. You can click on the links below to read any part of those essays.)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Two Questions about Life and Meaning

What Do We Mean by Meaning?

Should We Ask About Meaning?

Western Religions: Are They True?

Western Religions: Are They Good?

Western Religions: Do They Reveal Meaning?

Eastern Religions and Meaning in Life

Part 3 – Philosophy, Science, and Meaning

8. Western Philosophy and Meaning in Life

9. Science and Meaning in Life

10. Is Meaning in Life Enough?

Is There A Heaven?

Death is Bad For US

Individual Death and Meaning

Cosmic Death and Meaning

Scientific Immortality: Individual and Cosmic

Part 5 – Transhumanism and Meaning

A Fully Meaningful Cosmos

Transhumanism and Fully Meaningful Cosmos

Transhumanism and Religion

Cosmic Evolution and the Meaning of Life

The Meaning of Life

Part 6 – Skepticism and Meaning

21. Skepticism and Meaning

22. Back to Nihilism

Part 7 – Optimism and Hope

23. Attitudinal Optimism

24. Attitudinal Hope

25. Wishful Hope

Part 8 – Hope and Meaning

26. What I Hope For

27. The Source of Hope

28. Ignorance as a Justification of Hope

29.Hope and Meaning

30. Losing Hope

31. What Hope Recommends

32. Is Hope Enough?

Continue -> Preface

December 26, 2019

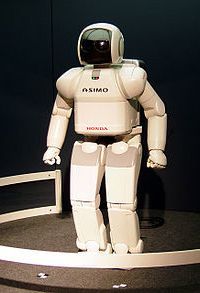

The Future of Being Human

The Institute of Art and Ideas runs an online ideas platform IAI.TV that’s been described as ‘Europe’s answer to TED.’ They have recently published a new academy course, “The Future of Being Human,” taught by Oxford University’s Future of Humanity Institute Fellow Anders Sandberg. The course is free to join. In the course, Anders covers the roots of transhumanist thinking and the possibilities of extending human life as we currently know it. You can view the course here. Below is a more detailed description of the course. Again the video course is free.

About the Course

Since the Ancient Greek legend of Icarus and Daedulus, humans have been fascinated by the potential of technology to transcend our biological limitations – to live longer, think smarter, and experience more. But what exactly could be achieved? Could we really do away with the nuisances of aging and death? Could our neural systems be put online, giving us the wealth of all human knowledge a thought away? Is this something we would even want? What are the dangers involved, and is it even possible to predict them? Are we in a position to even speculate about the effect of a transhumanist revolution would have on society, or is the uncertainty too great and risks too unpredictable? In this course, Fellow at Oxford’s Future of Humanity Institute Anders Sandberg explains the history, motivations and goals of transhumanism, and offers predictions of what humanity might resemble in a trillion years.

By the end of the course, you will have learned:

the reasons behind the unprecedented success of our species

the classical and religious roots of modern transhumanist thinking

the ways amateur transhumanists are modifying themselves today

why we age, and whether we can stop doing so

the dangers and costs of progress in genetic engineering

where meaning might be found in a life where anything is possible

As part of the course, there are in-video quiz questions to consolidate your learning and discussion boards to have your say.

IAI Academy courses are designed to be challenging but accessible to the interested student. No specialist knowledge is required.

About the Instructor

Anders Sandberg

James Martin Fellow at the Future of Humanity Insitute at Oxford University, his research centres on the ethical and social implications of future technologies and human enhancement.

Course Syllabus

Part One: Transformative Technologies

What physical and mental feats could enhanced humans achieve, and what has been achieved already?

Part Two: Transformed Societies

What would a transhuman society look like, and when might we expect to see it?

December 23, 2019

“A Meaning to Life,” Reply to Ruse

[image error][image error]

My last post expressed my effusive praise for Michael Ruse’s new book, A Meaning to Life. I would now like to comment on Ruse’s counsel that we can create and enjoy meaning in life despite the yearning for some non-existent salvific narrative—religious or scientific.

Ruse’s thoughts here echo those of various thinkers including Aristotle, Sartre, Barnes, Taylor, Hare, Singer, Thomson, Rachels, Frankl, Belshaw, Thagard, and Critchley all who agree in different ways that we create meaning in our lives.

A Meaningful Life

I would argue that certain universal human goods provide the deepest fulfillment and meaning. These goods include knowledge, friendship, health, skill, love, autonomy, fulfilling work, and aesthetic enjoyment. Such goods benefit us independently of whether we desire them because they fulfill our biological, psychological and social nature. The idea that good, happy, and meaningful lives involve universal human goods goes back at least to Aristotle. I think Ruse would agree with me thus far.

2. Is This Enough?

But should we be satisfied with the meaning available in life or should we want more? On the one hand, if our desire for meaning is too limited we will be too easily satisfied with our lives and the state of the world. On the other hand, if our desire for meaning is too great we will be too easily dissatisfied with our lives and the state of the world. So we should be content enough to experience the meaning life offers while discontent enough to want there to be more. I admit, though, the difficulty in balancing our outrage at suffering, injustice, and meaninglessness with a healthy dose of equanimity, acceptance, and serenity.

We should then be grateful to be the kinds of beings who can live meaningful lives. If that is all life can give, we should be satisfied. Ruse thinks we should be satisfied.

3. Death

The reason we might still be dissatisfied is that we die. Now many intellectuals claim that death is really good for us because immortality would be boring, hopeless, or meaningless. (Ruse suggests as much.) But people who say such things either really want to die or they deceive themselves. I think it’s generally the latter—they adapt their preferences to what seems inescapable. Happy, healthy people almost never want to die and are despondent upon receiving a death sentence. People cry at the funerals of their loved ones, accepting death only because they think it’s inevitable. I doubt they would be so accepting if they thought death avoidable.

So here’s our situation. After all the books and knowledge, memories and dreams, cares and concerns, effort and struggle, voices and places and faces, then suddenly … nothing. Is that really desirable? No, it isn’t. Death is bad. Death should be optional. Ruse seems to have a more negative view of immortality and a more positive view of death than I do.

4. Transhumanism

Transhumanism is an intellectual movement that aims to transform and improve the human condition by developing and making available sophisticated technologies to greatly enhance human intellectual, physiological, and moral functioning. Transhumanism is based on the idea that humanity in its current form represents an early phase of its evolutionary development. A common transhumanist thesis is that human beings may eventually transform themselves into beings with such greatly expanded abilities that they will have become godlike or posthuman. Notably, this includes defeating the limitation imposed by death.

Like Ruse, I don’t believe in any religious conception of an afterlife yet I would argue that transhumanism provides at least a realistic possibility of defeating death and potentially giving life more meaning. Transhumanism offers the possibility of a salvific narrative grounded in science and technology, something Ruse doesn’t address. I’ll admit to being skeptical about whether this potential future will be actualized—Ruse may be right that Murphy’s law generally prevails. But at least we have some non-supernatural reason to hope that the future will be more meaningful. Not sure how familiar Ruse is or what he thinks of transhumanism.

5. Cosmic Evolution

Ruse also mostly dismisses the idea of evolutionary progress, especially along the lines of thinkers like Julian Huxley and E.O. Wilson. While I hesitate to enter into a debate on this topic with a world-class authority on such matters as Ruse, perhaps transhumanism might shed a different light on this as well.

Think of it this way. If the big bang could expand to become a universe almost a hundred billion light-years across, if some of the atoms in stars could become us, and if unconscious random genetic evolution and environmental selection could give rise to conscious beings, then surely our (possible) transhuman descendants can direct cosmic evolution toward more perfect forms of being and consciousness. Or perhaps the universe is consciously doing this itself, as some panpsychists suggest.

Consider this cosmic vision. In our imagination, we exist as links in a golden chain leading onward and upward toward higher levels of being, consciousness, truth, beauty, goodness, justice, joy, love and meaning—perhaps even to their apex. We dream that our descendants will gradually transform and perfect their moral and intellectual natures, make themselves immortal, and bring about a fully meaningful reality. And if all this comes true then there is a meaning of life. Now I understand this is a highly speculative, mystical conception of the future but it is at least plausible. Ruse is skeptical of notions of progressive cosmic evolution.

6. Contentment is Easier for College Professors

Ruse is thankful for the good life he has lived and doesn’t expect more from life than it now offers. He certainly doesn’t desire or entertain any ideas about personal immortality. I commend him for living, as E.D. Klemke put it, “without appeal.” (Note that it is easier to be content if you’ve had access to quality health care, good education, clean water, political stability, etc. than it is for the millions who don’t have these things. I had many advantages and I’m guessing Ruse did too.) I’m guessing Ruse would grant the parenthetical remark.

7. Hope

I do agree with Ruse that we can never know intellectually whether life has a meaning or not. Again, I would suggest that a reasonable kind of hope is what keeps us going. As James Fitzjames Stephens taught me long ago:

We stand on a mountain pass in the midst of whirling snow and blinding mist, through which we get glimpses now and then of paths which may be deceptive. If we stand still we shall be frozen to death. If we take the wrong road we shall be dashed to pieces. We do not certainly know whether there is any right one. What must we do? ‘Be strong and of a good courage.’ Act for the best, hope for the best, and take what comes … If death ends all, we cannot meet death better.

Still, of any proposed solutions about life and meaning, we can always ask whether it’s enough. But then, what would count as enough? The problem is that nothing is enough if we expect definitive answers to our questions about life and meaning. If our expectations are too high they will be dashed. Our questions simply don’t allow for the precision of mathematics or physics—the best we can do is to adumbrate. But if there is a voluntary component here, if we have a modicum of free will, then we can be optimistic, we can hope. And while this isn’t an answer, being optimistic and having hope helps us live well.

Of course, some will still not be satisfied. They imagine that Apollo lives on Mt. Olympus and gives life meaning or they accept some other childish nonsense. Many prefer having the void as purpose rather than being devoid of purpose. They are so forlorn that the bromides of popular religion, philosophy, and politics appeal to them.

But if we accept our ignorance in this infinite and to us mostly unknown universe and if we reject illusory nonsense, then we can begin to better understand how we might play a meaningful part in a cosmic drama that leads, hopefully, onward and upward to higher levels of being and consciousness. We may really be as links in that golden chain.

So let us reject pain, suffering, death, and destruction and try to create a better and more meaningful reality. We must grow up and take our destiny into our own hands. For we are responsible for the truth and lies, the beauty and the ugliness, the love and the hate. And we can find meaning in life by playing our small role in making life increasing meaningful. Surveying our long past and indefinite future I’ll end by echoing the poetry of the great biologist Julian Huxley:

I turn the handle and the story starts:

Reel after reel is all astronomy,

Till life, enkindled in a niche of sky,

Leaps on the stage to play a million parts.

Life leaves the slime and through the oceans darts;

She conquers earth, and raises wings to fly;

Then spirit blooms, and learns how not to die,

Nesting beyond the grave in others’ hearts.

I turn the handle; other men like me

Have made the film; and now I sit and look

In quiet, privileged like Divinity

To read the roaring world as in a book.

If this thy past, where shall thy future climb,

O Spirit, built of Elements and Time!

December 22, 2019

“A Meaning to Life,” Reply to Ruse

[image error] [image error]

My last post expressed my effusive praise for Michael Ruse’s new book, A Meaning to Life. I am especially interested in Ruse’s counsel that we enjoy the meaning life has to offer without yearning for some salvific narrative—religious or scientific. The life we have, he says, is enough.

I very much like this idea of being content with what life has to offer and I have advocated this exact idea in my own writing. Here is an excerpt:

But should we be satisfied with the meaning available in life or should we want more? On the one hand, if we have too few desires we will be too easily satisfied with our lives and the current state of the world. On the other hand, if we have too many desires we will be too easily dissatisfied with our lives and the current state of the world. So we should be content enough to experience the meaning life offers while discontent enough to want there to be more. Still, I admit that it is hard to balance our outrage at suffering, injustice, and meaninglessness with a healthy dose of equanimity, acceptance, and serenity.

Again, we should be grateful to be the kinds of beings who can live meaningful lives. If that is all life can give, we should be satisfied. Still, we can imagine that the meaning in our lives prefigures some larger meaning. We can envisage—and we desire—that there is a meaning of life.

So I agree that the idea of eliminating or at least decreasing our desires—advocated variously by the Buddhists and the Stoics—is a good prescription for our own happiness, especially concerning desires for material things or physical pleasures. But my desire concerns wanting the lives of others to be better, especially those of future people. And as I have written I think transhumanism is a realistic, scientific philosophy that may allow us to live more meaningful lives than we do now. (Remember too that it is easier to be content if you’ve lived with access to quality health care, good education, clean water, political stability, etc. Much harder to be content for the millions who don’t have such luxuries.)

Ruse is thankful for the good life he has lived and doesn’t expect more from life than it now offers. He certainly doesn’t desire or entertain any ideas about personal immortality. I commend him for living, as E.D. Klemke put it, “without appeal.” My point is that life could offer more if we improve it. It is at least possible that our descendants achieve greater levels of being and consciousness, and experience more meaning. Now I fully acknowledge skepticism about whether this will happen, and I admit that only a reasonable hope keeps us going. My point is simply that there are some reasons to believe that the future may be better than the past or the present. That in large part is what keeps some of us going.

In the end, I’ll voice my agreement with both Ruse and Haldane: “My own suspicion is that the Universe is not only queerer than we suppose, but queerer than we can suppose.” That may not be much to hang your hat on, but it provides some small, and yet intellectually-honest, consolation.

December 20, 2019

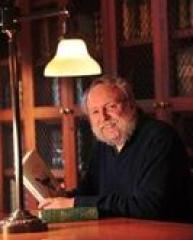

Review of “A Meaning to Life” by Michael Ruse

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

Michael Ruse (1940 – ) is a philosopher of science who specializes in the philosophy of biology, the relationship between science and religion, the creation-evolution controversy, and the demarcation problem within science. His most recent work, A Meaning to Life, is one volume in the Philosophy in Action series from Oxford University Press. (I have read many of his books through the years—he is an especially erudite scholar.)

The first chapter, entitled “The Unraveling of Belief,” explains (roughly) how the medieval Christian worldview slowly unraveled, primarily because of the Renaissance, the Reformation, and the Scientific Revolution—especially Darwinism.

In the world of the struggle for existence and natural selection, everything, including us humans, is simply the product of the blind forces of nature—no rhyme, no reason, no meaning or Meaning. Forget about eternal bliss and that sort of thing. You are not going to get it down here, and you are not going to get it up there. Truly, in the words of Camus, nigh a century later, life is absurd. (53)

But is this conclusion drawn too hastily? The rest of the book tries to answer this question.

The second chapter, “Has Religion Really Lost The Answer?” explores the extent to which religion can survive the scientific onslaught and still provide meaning. Consider first some questions science hasn’t so far sufficiently answered: 1) why is there something rather than nothing? 2) why be moral? 3) why are we consciousness? 4) what is the meaning of life?

Now Christianity does answer such questions—God, God, God, and God—but the problem is that it takes faith to believe all this, a faith Ruse lacks. Why? He offers a number reasons especially: 1) the existence of evil; 2) the problem of different faiths (it’s unlikely that yours is the true one); and 3) the irreconcilability of the Greek and Jewish conceptions of God; the former being abstract, outside of space and time, while the latter is personal.

Buddhism also answers these questions. For instance, life has meaning because of the possibility of attaining nirvana. But the issue here, as it was for Christianity, is whether religious claims are true. And Ruse simply doesn’t believe in Nirvana or reincarnation. As for those who insist that non-believers believe anyway and are doomed if they don’t, Ruse replies, “Don’t be so condescending—and dangerous. That kind of thinking led to the Inquisition. Darwinism opened the void. Religion doesn’t fill it.” (96)

Chapter 3, “Darwinism As Religion,” asks whether Darwinism itself provides answers to questions about life’s meaning. Can an evolutionary worldview give us an objective meaning of life? Can it show us how to live? Or can it at least give us subjective meaning? Ruse is skeptical of Darwinism as religion despite the efforts of great thinkers like Herbert Spencer, T. H. Huxley, Julian Huxley, and E. O. Wilson. They all emphasize progress as central to life’s meaning but Ruse is ultimately skeptical of claims about progress.

The argument connecting progress and evolution is straightforward. Evolution is progressive and over time creates more meaning. As a part of this process, we should try to steer evolution toward higher and more meaningful states of being and consciousness. But here Ruse reaffirms his skepticism. “Regular religion can’t do the job, so make up a naturalistic religion of your own. Neither approach takes the Darwinian revolution as seriously as it should … Darwinian thinking takes meaning out of the world.” (131)

So we are on our own after all. How then to avoid despair?

The final chapter, “Darwinian Existentialism,” attempts to present a naturalistic, subjectivist answer to the question of life’s meaning from a Darwinian perspective. The relevant insight from existentialism is that meaning must be found within. And for Ruse, this search must be informed by an evolutionarily view of our biological and social nature. So what is a meaningful life in a Darwinian world? It is, as Aristotle argued, to live in accord with our human nature. We create meaning through a love of family and friends, our moral life in society, fulfilling work, art, literature, music, and in the life of the mind.

But what if we still long for the big Meaning that religion promised? “As one who was brought up intensely religious, I would be a liar if I denied that there is always that lingering trace of sadness at hope extinguished.” (161) But do we really want the promises of religion? To be continually reincarnated or spend an eternity sitting on a cloud playing the harp. Ruse thinks not. But, you might object, surely eternity is better than that. Ruse replies that we simply have no idea of how to visualize what eternity could even be like.

Where does this leave Ruse?

… I can give you a good Darwinian account of Meaning in terms of our evolved human nature. This is not a weak substitute. This is the real thing. I have worked hard in my life to do what I do—raise five children, teach for over forty years, write more books than it is decent to count. I have found it immensely satisfying. I see no reason to expect anything beyond this. From an eternity of oblivion. To an eternity of oblivion. Everlasting dreamless sleep, without the need to get up in the middle of it to go to the bathroom. Absurd if you will, although I would not call it this. In the end, … I am an agnostic. I just don’t know whether life has any … Ultimate Meaning. (169)

In support of his agnosticism Ruse quotes J. B. S. Haldane, “My own suspicion is that the Universe is not only queerer than we suppose, but queerer than we can suppose.” And Ruse concludes with some advice, “There may be something more. There may not. Don’t spend your life agonizing about this or letting people manipulate you with false promises. Think for yourself … Life here and now can be fun and rewarding, deeply meaningful.” (170)

______________________________________________________________________

Let me express my sincere appreciation to Professor Ruse for this carefully and conscientiously crafted and deeply personal work. I will reply in a future post.

December 18, 2019

Depression and Truth

My last post elicited a comment from a reader apparently worried that, based on the contents of the post, I might be clinically depressed. Anyone who knows me personally would find this laughable, although my reader only knows me through my writing so that is an excuse. But the comment did get me to thinking.

First, the comment confused an assessment of human nature and existential reality with the author’s psychological state. I believe that humans are flawed because of their intellectual wiring and that the meaningfulness of life is largely in doubt. (I nonetheless emphasize hope throughout my voluminous writings on meaning and life.) I am also a happy man with a loving wife of 40 years and kids and grandkids I adore and who, I’m confident, feel similarly about me. Life may be meaningless, but that’s not necessarily a reason to be pessimistic!

But even if someone is depressed (or otherwise ill) that doesn’t invalidate their arguments. To claim the opposite is to commit the “ad hominem” fallacy. Additionally, studies show that depressed individuals have a more accurate view of themselves and reality than non-depressed ones and that happy people may be somewhat delusional. So this gives us good reasons to lend more credence to the views of the depressed. I’m not sure I’d go that far but the main point is that the issue of depression is (mostly) irrelevant here.**

Secondly, while my reader may be genuinely concerned about me, the remark could also be interpreted as condescending. (One of the problems with the written word is that you don’t have non-verbal clues to help clarify someone’s intent.) Maybe my reader simply disagrees with me and concludes therefore that I should see a doctor. If that’s what my reader thinks I don’t believe that argument holds much weight.

But let me reiterate that the basic distinction is between an individual being clinically depressed or otherwise mentally ill (although many categories of the DSM-V are controversial) and being someone who is disappointed at the difference between the world as it is and as you wish it were—which is one of the main points I was trying to convey in my post. Perhaps I didn’t state this as clearly as I could have. If not Bertrand Russell expressed my sentiments exactly in his final manuscript:

Consider for a moment what our planet is and what it might be. At present, for most, there is toil and hunger, constant danger, more hatred than love. There could be a happy world, where co-operation was more in evidence than competition, and monotonous work is done by machines, where what is lovely in nature is not destroyed to make room for hideous machines whose sole business is to kill, and where to promote joy is more respected than to produce mountains of corpses. Do not say this is impossible: it is not. It waits only for men to desire it more than the infliction of torture.

There is an artist imprisoned in each one of us. Let him loose to spread joy everywhere.

__________________________________________________________________

**I’ll admit that the source of a view isn’t completely irrelevant to how seriously you consider someone’s opinion. For example, I don’t get my views about science from athletes or movie actors; I tend to discount arguments of the scientifically illiterate. Still, even here the arguments should be assessed on the basis of their strengths or weaknesses. The simple fact that an athlete or movie star presents an argument for flat earth (it’s spherical), against biological evolution (true beyond a reasonable doubt) or that vaccines cause autism (they don’t), the fact that they aren’t scientists doesn’t by itself make those arguments ridiculous. They’re ridiculous because they’re demonstrably false.

Arguments about morality and the meaning of life are somewhat different since they can’t be resolved in the same way that scientific arguments can. In such cases, we have to weigh the evidence as best we can and draw our own conclusions. Still, if someone were clinically depressed or psychopathic that would give us some reason to discount their views, though not a definitive reason to do so.

I believe it was Hume who said that a person’s philosophy mostly reflects their personality. That may be true. But some people, after nurturing the ability to assess impartially as far as this is humanly possible, are better at separating what they want to believe from what is likely to be true. I’ll grant there is no knock-down argument either way and the extent to which personality affects beliefs is an open question.

Finally, let me say that the scientific method is the best way that humans have ever created for doing separating truth from fiction. Our beliefs should be proportional to the reasons and evidence we have for or against them.

For more see mine and some of my contributors’ musings on epistemology: here, here, here, here, here, and here.

December 15, 2019

Personal Reflections at the end of 2019

British calendar, 1851, Metropolitan Museum of Art

British calendar, 1851, Metropolitan Museum of Art

There are many thoughts that pass through my mind in the course of a day or week. Many necessitate a book-length analysis to do justice to them, but that I won’t do! Instead, let me briefly mention a few of the things that I have recently pondered.

1. Does suffering eliminate the possibility of meaning? That is, even if the cosmos slowly evolves into a perfect state, does that justify all the suffering that led to such perfection? At first glance, it seems not. Dostoevsky advanced a similar argument in the Brothers Karamazov—no heaven can justify the gratuitous evil of the suffering of an innocent child. But if some cosmic plan—I doubt there is one exists—demands suffering then that’s a bad plan.

2. There are a few hypersane individuals among us but they’re probably the exception. And even so-called normal people, are often fanatics or fascists. I’m reminded of a Mark Twain quote: “Such is the human race. Often it does seem such a pity that Noah and his party did not miss the boat.”

3. Maybe humans are better than I think. Some argue they are unique among animals in the way they teach each other. Others argue that we distinguish ourselves from non-human animals by having involved fathers. In the words of Shakespeare, “What a piece of work is a man, how noble in reason, how infinite in faculties, in form and moving how express and admirable, in action how like an angel, in apprehension how like a god!” Then again, looking honestly at this world, we must wonder what Shakespeare was thinking.

4. When I think about my grandchildren I experience an overwhelming desire to shield them from the world. They are so innocent; they see no evil in the world; they have no sense of the danger that surrounds them. I now understand why Buddha’s parents wanted to keep him in the palace. I so wish they lived in a world that the could fully embrace.

5. I think humanity will probably destroy itself. For how will we master the residual selfish and violent instincts of our evolutionary past? How will we survive with a reptilian brain characterized by tribalism, territoriality, short-term thinking, cognitive bugs, etc.? How will reptiles armed with nuclear weapons avoid Armageddon? I just don’t know.

6. I was watching a video about starting a fire without matches. It’s really hard to do! Then the parallels with civilization became apparent. Think of how hard it was, how much labor and love and death went into creating a society in which I don’t have to start fires or hunt food. I turn my radiator handle and I get heat; I hunt at the grocery store. Neither requires much effort. It’s so easy to forget the horror and deprivation of the state of nature. How hard it would be to recreate it from scratch.

7. I was thinking about cults. Some say that when a few people believe something crazy it’s called a cult, and when many people believe something crazy, it’s called a religion. Others claim that a cult plus time equals religion. But let’s not single out religion. Consider the modern-day Republican/Trump party. They protect their fascist leaders like churches protect their child abusers. They are now a cult. And they excommunicate the heterodox.

8. Corruption is everywhere. I suppose the world has always been corrupt but, at least until early adulthood, I thought the world was basically alright. Now I have my doubts. I’m wondering if the problem is both in the stars and in ourselves. And if so, why is that? It seems that growing up is, in large part, leaving many of our dreams behind.

9. There is so much we don’t know about ourselves. We don’t understand our own motives, we deceive ourselves, and we overestimate our ability (Dunning-Kruger effect). All this assumes we have a self, as both Hume (bundle theory) and the Buddhists (no-self) deny. Buddhism, interestingly, may offer a way out of this paradox. My own hunch is that we are windows, vortexes, or apertures through which the universe temporarily becomes conscious. But then again this is too mystical for me. I just don’t know who I am.

10. We have so much information and so little time to sort through or analyze it—the amount of information in the world is unmanageable. I’d love to ponder it all, but I cannot. We also have a lack of wisdom in our world. The only ultimate solution I know of is to enhance our intelligence, as I have argued many times. It also occurs to me that the denigration of expertise is especially problematic when we can’t be experts at more than a very few things.

11. Violence is declining according to Steven Pinker in The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined[image error]. Many disagree with Pinker on this point including John Gray, Will Koehrsen, and Herman and Peterson. I think the major flaw in Pinker’s thinking here is that he doesn’t sufficiently account for existential risks. Historical data tells us almost nothing about what will happen tomorrow. Climate change, environmental degradation, or nuclear war may soon obliterate both the earth and Pinker’s hypothesis. Unimaginable violence may be right around the corner. I hope I’m wrong.

___________________________________________________________________________

Addendum – More Things To Think About

This article suggests that economic inequality is inevitable.

This article suggests that happiness isn’t a matter of relentless, competitive work.

This article suggests that I forget Plato, Aristotle, and the Stoics and embrace Epicureanism.