John G. Messerly's Blog, page 2

July 27, 2025

Review of Appleman’s: The Labyrinth: God, Darwin, and the Meaning of Life (Part 2)

(continued from the previous post)

(continued from the previous post)

Philip D. Appleman (1926 – 2020 ) was an American poet, a Darwin scholar, and Professor Emeritus of English at Indiana University. His final book was titled: The Labyrinth: God, Darwin, and the Meaning of Life[image error].[image error]

Cosmic evolution gave birth to our sun and planet; chemical evolution brought forth atoms, molecules, and cells; biological evolution led to us. The process ran itself; there was no intelligent designer. But consciousness emerged, we are here, and within limits, we are free. And yet we will die.

Charles Darwin died the night of April 18th, 1882. A biographer says that his last words were: “I am not in the least afraid to die.” How do we account for his courage? Appleman gives two reasons.

First, he was a mature man no longer frightened by superstitions. He once studied for the clergy, but he had “gradually come … to see that the Old Testament from its manifestly false history of the world, with the Tower of Babel, the rainbow at sign, etc., etc., and from it’s attributing to God the feelings of a revengeful tyrant, was no more to be trusted than the sacred books of the Hindoos, or the beliefs of any barbarian.” (42) He also believed religion was sadistic. “I can indeed hardly see how anyone ought to wish Christianity to be true; for if so, the plain language of the text seems to show that the men who do not believe, and this would include my Father, Brother, and almost all my best friends, will be everlastingly punished. And this is a damnable doctrine.” (43)

Darwin knew that death is natural; we die like all the other animals. The non-religious don’t fear death, but they rage at being mortal. Religion responds differently.

Religion says: console yourself, there will be another chance, another life. Two things are wrong with this. First, there is not a shred of evidence for it and, second, it is a sop, consciously intended to blunt our rage and regret, thus dehumanizing us. Our anger at death is precious, testifying to the value of life; our sorrow for family and friends testifies to our devotion. (45-46)

Confronted with death, we should see that meaning is found in what we have done, and what we have created—meaning can’t be imposed on us from the outside. Darwin was thus content, for “Darwin on his deathbed could look back on forty-three years of devotion to a loving wife, forty-five years of devotion to a grand idea … He had made his commitments and he had kept them.” (46-47)

If the meaning of life is simply the fabric of our whole existence, then no wonder our brief careers seem so illogically precious to us, so worth clinging to. Self-preservation … it’s always there, the fundamental imperative of life: survival. Preachers may sneer at this, but notice: they continue to pass the collection plate. (47)

To understand morality, we begin with self-preservation. However, we soon find that to survive, we must extend the sphere of our moral concerns beyond self to family, tribe, nation, and to the planet itself. Fortunately, cooperation is in our DNA. Darwin knew that “our social behavior might be to some extent inherited.” (49) He knew that our social instincts contain tendencies to be both selfish and altruistic.

“Once our species evolved to social consciousness and communal morality, people naturally began to express their social approval with praise, and to enforce their disapproval with contempt, anger, and ostracism.” (50) Long before religion codified morality, secular communities enforced it. Then we invented God, “thousands of years after evolution had developed our social instincts, religion co-opted our socially evolved good impulses and encumbered them with myriad disparate, controversial, and contradictory gods, priesthoods, scriptures, myths, and dogmas.” (51)

Still, many are motivated by their more base instincts. Religion deals with this problem with eternal reward or punishment.

But neither of these sanctions has ever worked very well, which is why (among other things) totally immersed Southern Baptists always performed the lynchings for the Ku Klux Klan; why nice Catholic boys have always run the Mafia; why a devout Jew murdered his peace-loving prime minister; and why, in a notorious American election, pious white churchgoing Christians voted two to one for a declared Nazi. (52)

The problem isn’t that people don’t know about right and wrong, but that they don’t care about it. How can people be taught to care? By social and political leaders? We know that survival depends ultimately on cooperation, but powerful politicians, financiers, and business people are among the most selfish people in society. Appleman’s sarcasm is caustic. The ruling class is strong; they “… all have enough strength to bear the misfortune of others.” (54-55)

For morals, we might look instead to science:

… science strictly speaking has no ethics … But our ethics … can hardly emerge from a vacuum … Scientific knowledge has at the bare minimum a selective ethical function, identifying false issues that we can reasonably ignore: imagined astrological influence on our moral decisions, for instance. Science offers us the opportunity of basing our ethical choices on factual data … rather than on misconceptions or superstitions … (55)

Of course, we can misuse scientific knowledge, but generally, the growth of science corresponds to social progress. Moreover, the scientific mind discovered that we are one species on one planet, connected to other living things on whom our survival depends. We should replace the arrogant claim that humans have dominion over the earth with a recognition that we can’t survive without the ecosystem.

The idea of the connection between all living things is particularly aroused by evolutionary biology. From this connection can spring a new ethics. As Darwin put it:

The moral faculties are generally and justly esteemed as of higher value than the intellectual powers. But we should bear in mind that the activity of the mind … is one of the fundamental though secondary bases of conscience. This affords the strongest argument for educating and stimulating in all possible ways the intellectual faculties of every human being. (60)

Appleman contrasts this intellectual outlook with the religious one. Religions often look at the evil in the world as acts of the gods or signs of the end of the world. (Think of those today who claim their god will take care of climate change.) Darwin understood such people: “To those who fully admit the immortality of the human soul, the destruction of our world will not appear so dreadful.” (61)

Today, we live in a world where people are comforted by “sensational crime, sporting events, the sexual behavior of celebrities, and religious escapism. Nourished on such pap, many people find themselves lost in the labyrinth of neurosis and succumbing to easy answers and seductive promises: the priests need not soon fear for their jobs.” (61-62) Most people won’t be converted to rigorous thought, but Appleman believes there is value in speaking out.

Every small light in the pervading darkness, from Giordano Bruno and Galileo to Thomas Paine and Charles Darwin to Margaret Sanger and Elizabeth Cady Stanton is valuable and necessary. Like characters in a perpetual Chekhov drama, we can imagine a more enlightened future age looking back on our time with distaste and incredulity but nevertheless acknowledging those voices in our wilderness who kept the Enlightenment alive until humanity in general became worthy of it. (62)

Moreover, the entire history of the law, Appleman says, records our transition from barbaric religious punishment and religiously sanctioned slavery to a more humane secular law. The basis of morality is a social contract. However, if some don’t benefit from the contract, they will resent the current order. In the long run, they will not be satisfied with the claim that all will be well in heaven. “What is required is a secular solution, which works the other way around: Improve the society, and most people will behave better.” (Look at the Scandinavian countries.)

In the past, slavery was defended by “conservatives, slave-owners, and most religions.” We look back with horror, as our future descendants will at the way we treat blacks, women, and other minorities.

Humane and liberal societies gradually come to a more sensitized understanding of the plight of the less fortunate and devise sensible ways of assisting them; the underclass then feels less trapped, becomes less confrontational, and is less motivated to break the social contract. Good laws and good customs precede good behavior. (67)

In short, morality is in everyone’s self-interest. A more moral society would encourage people to reflect about their own lives, to learn about the world, to reject superstition, and to assess human problems with reason and compassion.

Free from the racking fear of deprivation and from the labyrinth of brutal religious animosities, free from holy nonsense and pious bigotry, living in a climate of openness, tolerance, and free inquiry, people would be able to create meaning and value in their lives: in the joy of learning, the joy of helping others, the joy of good health and physical activity and sensual pleasure, the joy of honest labor; in the richness of art and music and literature and the adventures of the free mind; and in the joys of nature and wildlife and landscape—in short, in the ephemeral but genuine joy of the human experience.

That joy does not depend upon mysticism or dogma or priestly admonition. It is the joy of human life, here and now, unblemished by the dark shadow of whimsical forces in the sky. Charles Darwin’s example, both in his work and in his life, help us to understand that that is the only “heaven” we will ever know. And it is the only one we need. (68-69)

I thank Professor Appleman for his wonderfully written book. In tomorrow’s post, I will reflect on all he has said.

July 20, 2025

Review of Appleman’s: The Labyrinth: God, Darwin, and the Meaning of Life (Part 1)

Philip D. Appleman (1926 – 2020 ) was an American poet, a Darwin scholar, and Professor Emeritus of English at Indiana University. His final book was titled: The Labyrinth: God, Darwin, and the Meaning of Life[image error].[image error]

It is a short book, only about 60 pages, but it is carefully and conscientiously crafted, so I will quote extensively from its beautiful prose. Here are its first sentences:

The simpler the society, the cruder the problems: we can imagine Neanderthals crouching in fear—of the tiger, of the dark, of thunder—but we do not suppose they had the leisure for exquisite neuroses. We have changed all that. Replete with leisure time and creature comforts, but nervously dependent on a network of unfathomable technologies, impatient with our wayward social institutions, repeated betrayed by our spiritual” leaders, and often deceived by our own extravagant hopes, we wander the labyrinth asking ourselves: what went wrong? The answers must begin with our expectations. What is it we want? And why? What kind of people are we? (11)

We are, as Appleman knows, “A beast condemned to be more than a beast: that is the human condition.” We know our lineage; we are brothers of primates, sharing over ninety-eight percent of our DNA with chimpanzees. The legacy of more than one hundred and fifty years of scientific research confirms this central fact—we are modified monkeys who came to dominate other animals because of our large brains. But the brains that created tools also imagined they were the chosen people of the gods, that all other flora and fauna were expendable. This was our true loss of innocence. The notion that “God wills it” serves aggressor nations and species alike. The assault on nature came with the gods’ permission, but it was an arrogant assumption, dissociated from reality, unstable, and self-destructive. “In our fantasies of godlike superiority are the seeds of neurosis, and when they bear their dragon fruit, we run for the mind healers.”(14)

God is an invention of our imagination and for many people a seductive idea. (Appleman has in mind the Judeo-Christian God, but this idea would apply to other gods as well.) “People in general have never exhibited much passion for the disciplined pursuit of knowledge, but they are always tempted by easy answers. God is an easy answer.” (16) A brain capable of asking questions without answers satisfies itself that some god is the answer, even though this is no answer—the term god only hides our ignorance.

But belief in the gods survives because it is useful. Gods sanction war and, given that they are omnipotent and omniscient, a multitude of evils, too. And they receive undeserved praise for saving our lives when, for example, thousands have just died in natural disasters. After all, there must be some reason why we were saved, we think, because our brains see patterns everywhere. In the stars, they see Aquarius and Capricorn; in the heavens, they see angels and archangels. No wonder religion hates knowledge—the gods depend upon our ignorance.

Learning is hard work; imagining is easy. Given our notorious capacity for indolence, is it any wonder that school is so unpopular, faith so attractive? So we fumble through the labyrinth of our lives, making believe we have heard answers to our questions, even to our prayers. And yet, deep down, we know that something is out of joint, has always been out of joint. (18)

Beginning as infants, selfish and full of desire, we soon realize that growing up means limiting our desires. By contrast, theologies offer infinite delight—it’s all so tempting. Of course, we can’t be sure we’ll win the eternal prize because that depends on God’s grace, given or withheld according to the capriciousness of the gods. Still, most assume we are favored by the gods. Thus, religion panders to childish wishes, leaving us unfit to deal with reality. It turn our attention away from this world toward the afterlife, and it often leads to horrific behavior.

Appleman says that the immoral people he has known were mostly believers, whereas his agnostic and atheist friends were quite virtuous. This is because religious people can afford to be immoral; all they need to do is ask forgiveness. “If God exists, as the old saying should go, then anything is permissible. Nonreligious people have no easy way out. Their moral accountability is not to some whimsical spirit in the sky, famous for easy absolutions … They must account to themselves and live with their own conduct…” (23)

Appleman also argues that unbelievers “are less perverted by the antisocial tendencies of religious thinking, including the seductions of fanaticism … To the fanatical mind, the act of pure religion has always been an act of pure violence …” (24-25) He provides numerous examples of religious wars and cruelty to buttress his argument, making his point in powerful prose: “Religion stalks across the face of human history, knee-deep in the blood of innocents, clasping its red hands in hymns of praise to an approving God.” (27) Yet we are all supposed to approach religion with deference, despite the fact that in the holy people “we encounter a veritable Chaucerian gallery of rogues and felons.” (27-28) Appleman provides a long list of such characters from just the last few years alone.

The religions of the world don’t wish to be judged by their deeds. They are not interested in their victims but in “the towering cathedral, and soaring rhetoric, and official parades of good intentions.” (29) Appelman attributes this public relations success to the organizational ability of religions. Beginning with visions, prophecies, and other subjective experiences, the priesthoods became organized. Subsequently, the original vision, whether it was for good or ill, is forgotten:

… and the organization itself becomes the object of self-preservation, aggrandizing itself in monumental buildings, pompous rituals, mazes of rules and regulations, and a relentless grinding toward autocracy. None of the other priesthoods managed all this as successfully as the early Christian clergy … Thus the “Roman” Church created for itself a kind of secular immortality sustained by a tight network of binding regulations, rigid hierarchies, and local fiefdoms, which people are born into, or are coerced or seduced into—and then find that confining maze almost impossible to escape from.” (30-31)

Large religious organizations create great problems—crusades, inquisitions, war, genocide, and burning scientists at the stake. Today, the Roman Catholic Church, to take one example, has used its power and influence to oppose birth control. Needless to say, this policy leads to hunger, poverty, disease, death, the degradation of the environment, and more. Under the guise of doing good, the religious wreck lives. “There is a word for this kind of activity, talking about love while blighting people’s lives: it is hypocrisy.” (32-33)

The result of this fascination with otherworldly concerns manifests itself in our distaste for the satisfactions of this world. If we truly believed in the gods, then we wouldn’t care about art, music, love, sex, money, and power. But most people only give lip service to their religion, almost no one sacrifices the things of this world for the afterlife ” … few people are abjuring the world; we are taking the cash and letting the credit go …” (34) Still, many can’t let go of worrying about the afterlife or rejecting their native religion. But Appleman counsels us to reject “the bribes of the afterlife” and our childish longing for gods, we can truly find meaning in this world precisely because what’s here is not eternal.

Doomed to extinction, our loves, our work, our friendships, our tastes are all painfully precious. We look about us, on the streets and in the subways, and discover that we are beautiful because we are mortal, priceless because we are so rare in the universe and so fleeting. Whatever we are, whatever we make of ourselves: that is all we will ever have—and that, in its profound simplicity, is the meaning of life. (35)

We are beasts that ponder the meaning of life. We were not designed by gods, there is no design outside of us, only the design we create. From our self-chosen actions, we get our happiness, our truth, our freedom, our wisdom, and our meaning. But how can there be meaning if there is death? Our brains provide the reasons. Rejecting the “mumbo-jumbo of theologians,” we search for the truth.

(I will continue with Part 2 next week. )

July 13, 2025

David Foster Wallace – This Is Water

[I first published the following post almost ten years ago. Pursuant to a recent reread, I decided it deserved a reprinting.]

Below is a summary of and commentary on David Foster Wallace‘s (1962 – 2008) famous commencement speech: “This Is Water: Some Thoughts, Delivered on a Significant Occasion, about Living a Compassionate Life.” Its themes include solipsism, loneliness, monotony, education, and the importance of sympathy and conscious awareness.

(At the bottom of this page is an audio of the entire speech.)

Wallace begins with a parable:

There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says “Morning, boys. How’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes “What the hell is water?”

Wallace quickly explains that “The point of the fish story is merely that the most obvious, important realities are often the ones that are hardest to see and talk about.” Against the story’s backdrop, he argues that the significance of a liberal arts education isn’t so much about learning how to think, but that it provides “the choice of what to think about.”

To explain this idea, consider that most of us are close-minded, unaware of how imprisoned we are to the ideas and events that continually shape us—to the water all around us. In contrast, a real education teaches us: “To be just a little less arrogant. To have just a little critical awareness about myself and my certainties. Because a huge percentage of the stuff that I tend to be automatically certain of is, it turns out, totally wrong and deluded.”

In particular, a liberal arts education gives us tools to escape from our default settings, from the things we believe to be obvious, but which really aren’t. For education

… means learning how to exercise some control over how and what you think. It means being conscious and aware enough to choose what you pay attention to and to choose how you construct meaning from experience. Because if you cannot exercise this kind of choice in adult life, you will be totally hosed …

If you’re truly educated, you can “keep from going through your comfortable, prosperous, respectable adult life dead, unconscious, a slave to your head and to your natural default setting of being uniquely, completely, imperially alone day in and day out.” And to show why this is important, Wallace informs the new graduates:

The plain fact is that you graduating seniors do not yet have any clue what “day in day out” really means. There happen to be whole, large parts of adult American life that nobody talks about in commencement speeches. One such part involves boredom, routine, and petty frustration. The parents and older folks here will know all too well what I’m talking about.

To explain this, Wallace pictures an average day in the near future for college graduates:

you get up in the morning, go to your challenging, white-collar, college-graduate job, and you work hard for eight or ten hours, and at the end of the day you’re tired and somewhat stressed and all you want is to go home and have a good supper and maybe unwind for an hour, and then hit the sack early because, of course, you have to get up the next day and do it all again. But then you remember there’s no food at home. You haven’t had time to shop this week because of your challenging job, and so now after work you have to get in your car and drive to the supermarket. It’s the end of the work day and the traffic is apt to be: very bad. So getting to the store takes way longer than it should, and when you finally get there, the supermarket is very crowded, because of course it’s the time of day when all the other people with jobs also try to squeeze in some grocery shopping … So the checkout line is incredibly long, which is stupid and infuriating. But you can’t take your frustration out on the frantic lady working the register, who is overworked at a job whose daily tedium and meaninglessness surpasses the imagination of any of us here at a prestigious college.

This is the life that awaits young graduates. It will be their life “day after week after month after year.” But we can choose to be upset or frustrated about the store or the traffic, or we can reject this natural default setting. Instead, we can see that all of this isn’t about us; we can learn to see things differently. Perhaps those in traffic or at the store are as stressed as we are. Perhaps their lives are much worse than ours. It’s hard to see the world like this, but we can do it with effort. As Wallace poetically puts it:

If you’re automatically sure that you know what reality is, and you are operating on your default setting, then you, like me, probably won’t consider possibilities that aren’t annoying and miserable. But if you really learn how to pay attention, then you will know there are other options. It will actually be within your power to experience a crowded, hot, slow, consumer-hell type situation as not only meaningful but sacred, on fire with the same force that made the stars: love, fellowship, the mystical oneness of all things deep down.

Wallace’s point is that “The only thing that’s capital-T True is that you get to decide how you’re gonna try to see it. (This is what the Stoics advised, too.) This, I submit, is the freedom of a real education, of learning how to be well-adjusted. You get to consciously decide what has meaning and what doesn’t. You get to decide what to worship.” (Jean-Paul Sartre offered similar advice.) Worshipping money, power, or physical beauty will not satisfy, for you will never have enough of them. These are the things the world encourages us to worship, what we worship by default. Yet

The really important kind of freedom involves attention and awareness and discipline, and being able truly to care about other people and to sacrifice for them over and over in myriad petty, unsexy ways every day. That is real freedom. That is being educated, and understanding how to think. The alternative is unconsciousness, the default setting, the rat race, the constant gnawing sense of having had, and lost, some infinite thing.

Wallace concludes:

… the real value of a real education, which has almost nothing to do with knowledge, and everything to do with simple awareness; awareness of what is so real and essential, so hidden in plain sight all around us, all the time, that we have to keep reminding ourselves over and over: “This is water.” “This is water.” It is unimaginably hard to do this, to stay conscious and alive in the adult world day in and day out. Which means yet another grand cliché turns out to be true: your education really IS the job of a lifetime. And it commences: now. I wish you way more than luck.

I thank Wallace for reminding me that education is about choosing to escape our biological and cultural default settings; that we can only control our minds, not the external world; that real education is a lifelong process; and that the meaning of life is found, if anywhere, in ordinary things. Finally, I would like to thank all the friends and teachers who helped provide me with a liberal arts education so long ago. It has not made me rich, but it has helped make me free.

And here is the speech in full.

Note – Out of respect for DFW’s memory, I did not discuss the few sentences in the middle of the speech relating to suicide.

July 6, 2025

The Metaphysical Beekeeper

From “The Bad Beekeeping Blog,” by Ron Miksha.

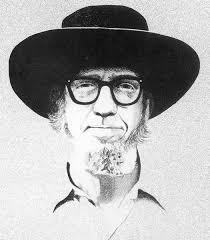

He died [more than] 20 years ago. But Richard Taylor is interesting enough to remember, … Here’s my tribute … which celebrates the great commercial beekeeper, writer, and philosophy professor …

Today is the anniversary of the birth of our beekeeper-hero, Professor Richard Taylor. A commercial beekeeper with just 300 hives, he was an early champion of plastic bee equipment and the round comb honey system. He was also a philosopher who “wrote the book” on metaphysics. He really wrote the book on metaphysics – for decades, his college text Metaphysics introduced first-year philosophy students to the most fundamental aspect of reality – the nature of cosmology and the existence of all things.

Although his vocation of philosophy was speculative, unprovable, and abstract to the highest degree, Richard Taylor was as common and down-to-earth as it’s possible to become – with some minor tinges of eccentric behaviour added to the mix. I will write about his philosophy and how it shaped his politics, but first, let’s celebrate his beekeeping.

Richard Taylor and his twin brother were born November 5th, 1919. It was shortly after their father had died. That left a widowed mother to raise an impoverished family during the Great American Depression. Richard was fourteen when he got his first hive of bees in 1934 – the year that a quarter of Americans were unemployed and soup lines leading to Salvation Army kitchens stretched for blocks. He began beekeeping that year, and except for submarine duty as an officer during World War II, he was never far from bees. He respected honest hard work and the value of a penny, but as a young man, he nevertheless drifted unfocussed, trying college, then quitting, and then taking various uninspiring jobs.

In the US Navy, he spent evenings on his bunk in a sub, descending into the gloomy passages of Arthur Schopenhauer. Somehow the nihilistic philosopher appealed to Taylor and ironically gave him an interest in life. This led Taylor back to school. He became a philosopher himself.

Richard Taylor earned his PhD at Brown University, then taught at Brown, Columbia, and finally Rochester, from which he retired in 1985 after twenty years. He also held court as a visiting lecturer at Cornell, Hamilton, Hartwick, Hobart and William Smith College, Ohio State, and Princeton. His best years were at Rochester where he philosophized while his trusted German shepherd Vannie curled under his desk. Richard Taylor sipped tea and told his undergrads about the ancient philosophers – Plato, Epicurus, Aristotle, Xeno, and Thales. In the earlier days, he often drew on a cigar while he illuminated his flock of philosophy students. Those who attended his classes remarked on his simple, unpretentious language. They also noted that he was usually dressed in bee garb – khakis and boots. As soon as the lecture ended and the last student withdrew from the hall, he and Vannie quickly disappeared to the apiaries.

Taylor, the hippie beekeeper

It may be unfair to describe Dr Richard Taylor as a hippie beekeeper, but perhaps he was exactly that. As a beekeeper, he was reclusive. He refused to hire help. Rather than deal with customers, he set up a roadside stand where people took honey and left money without ever meeting him. In his shop or out among his bees, Taylor disdained big noisy equipment. He sometimes took a lawn chair and a thermos of tea to his apiaries so he could relax and listen to the insects work, but I doubt that he did this much. Through the pages of American Bee Journal, Bee Culture, and several beekeeping books, he described best beekeeping practices as he saw them – and those practices required hard work and self-discipline more than relaxed lawn-chair introspection.

Running 300 colonies alone while holding a full-time job and writing a book every second year demands focus. His bees were well-cared for, each producing about a hundred pounds every year in an area where such crops are rare. By 1958, he was switching from extracting, which he disliked, to comb honey production, which he loved. Comb honey takes a more skilled beekeeper and better attention to details, but in return it requires less equipment, a smaller truck, and no settling tanks, honey pumps, whirling extractors, or 600-pound drums. “Just a pocket knife for cleaning the combs,” he said.

To me, it’s surprising that Richard Taylor embraced the round comb honey equipment called Cobanas. The surprising thing is that the equipment is plastic. Reading Taylor’s books, one realizes his affinity for simple tools and old-fashioned ways. In that context, plastic seems wrong. But it’s not.

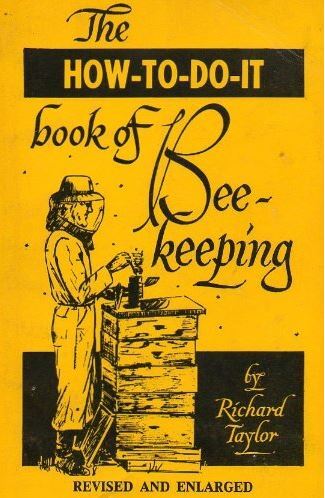

In the past, comb honey sections were square-shaped and made from wood. The wood had to be light-weight and soft enough to bend into boxes without breaking. The wood that suited this need in the eastern USA was basswood (also called linden, Tilia spp.). Early in the twentieth century, over a million comb honey sections were produced each year – leading to the destruction of forests of the stately nectar-producing trees. Plastic is light-weight, durable, and ultimately very practical for bee equipment. It can be recycled, a tangible benefit to a person as frugal as Richard Taylor. He was sure that Cobana equipment, invented by a Michigan physician in the 1950s, would lead to a simple practical way of beekeeping. Taylor was so enthused that in 1958, living in Connecticut, he wrote his first beekeeping article about the new plastic equipment for the American Bee Journal. Here’s the photo that accompanied his story.

Richard Taylor’s son, Randy, packing round comb honey, 1958. (Photo from ABJ).

His comb honey project worked. Richard Taylor, the beekeeper, was financially successful. In today’s dollars, his comb honey bee farm returned about $75,000 profit each year – a tidy sum for a hobby and more than enough spare change to indulge his habit of frequenting farmer’s auctions where he’d delight in carrying home a stack of empty used hive bodies that could be had for a dollar.

Taylor, the teacher

Richard Taylor immensely enjoyed teaching and lamented what he called “grantsmanship” which arose in America while he was a professor. Grantsmanship is the skill of securing funding for one’s projects while possibly ignoring the fundamental duties of teaching. Unethical grantsmanship, of course, can lead to big dollars flowing to researchers who are willing to claim that sugar, for example, does not contribute to obesity and cigarette smoke does little more than sharpen one’s senses. Richard Taylor saw the compromised atmosphere. He also regretted the demise of good faculty instructors replaced “largely by graduate students, some from abroad with limited ability to speak English. Lecturers who simply read in a monotone from notes are not uncommon,” he wrote.

Meanwhile, the (sometimes unethical) pursuit of grants was accompanied by the rise of the “publish or perish” syndrome. In his own field, Taylor pointed out that academic philosophers engaged in “a kind of intellectual drunkenness, much of which ends up as articles in academic journals, thereby swelling the authors’ lists of publications.” Taylor wrote extensively on this in 1989, saying that there were 93 (!) academic philosophy journals published in the USA alone that year – seldom read, seldom good, but filling mailboxes with material to secure a professor’s promotions.

This was not the academic world that Richard Taylor sought when he began his career in the 1950s, but it was the world he eventually left. Although he wrote 17 books – mostly philosophical essays but also several rather good beekeeping manuals – he didn’t publish many academic papers. He spent more time in the lecture halls and with his bees than he did “contemplating the existential reality of golden mountains and writing papers about them”, as he put it.

Taylor, the philosopher

I am only going to give this one short passage about Richard Taylor, the philosopher. He studied and taught metaphysics and ethics. His essays on free will and fatalism are renowned and influential, even today. I’ve never taken a philosophy course, so anything I say about the subject will probably end with me embarrassing myself. However, a few years ago, during a winter trip to Florida, a copy of Richard Taylor’s Metaphysics travelled with me. I read every word and I think that I understood it at the time. For me, most of it was transparent common sense. Since it was well-crafted and interesting, Taylor may have lulled me into believing that I understood his metaphysical description of the universe, even with just this cursory introduction. At any rate, I felt that what he wrote wasn’t different than what I’d come to discover on my own, although it was much more elegantly presented than I could ever manage.

Taylor, the Republican

When I saw Richard Taylor – just once, at a beekeepers’ meeting – I indeed thought that he was a hippie, a common enough form of beekeeper in the 1970s. His belt was baler twine and a broad-rimmed hat hid his face, though a scraggy beard protruded. I was surprised to later discover that Richard Taylor identified as a conservative and voted Republican. But he was also an atheist, advocated for women’s rights, and late in life (though proud of his military service) he became a pacifist, “coming late to the wisdom,” he said. He valued hard work, self-sufficiency, and independence. He disliked Nixon, but gladly voted for Reagan. He even wrote a New York Times editorial praising Reagan’s inaugural address while offering insight on what it means to be an introspective conservative in the 1980s.

At age 62, still a professor of philosophy at the University of Rochester, and the recent author of the book Freedom, Anarchy, and the Law, he penned that widely-circulated New York Times opinion piece. Taylor wrote that in Reagan’s inaugural address, the new president reminded us that “our government is supposed to be one of limited powers, not one that tries to determine for free citizens what is best for them and to deliver them from all manner of evil.” Richard Taylor then goes on to warn that “political subversion . . . is the attempt to subordinate the Constitution to some other philosophy or creed, believed by its adherents to be nobler, wiser, or better.”

Taylor warned of anti-constitutional subversion in American politics, “if anyone were to try to replace the Constitution with, say, the Koran, then no one could doubt that this would be an act of subversion . . . Similarly, anyone subordinating the principles embodied in the Constitution to those of the Bible, or to those of one of the various churches or creeds claiming scripture as its source, is committing political subversion.”

Taylor tells us that conservative spokesmen of Reagan’s era – he mentions Jerry Fallwell and others – are right saying that “it is not the government’s function to pour blessings upon us in the form of art, health, and education, however desirable these things may be.” Nor, Taylor said, is it constitutional for “the Government to convert schoolrooms into places for prayer meetings, or to compel impoverished and unmarried girls, or anyone else, to bear misbegotten children, to make pronouncements on evolution, to instruct citizens on family values, or to determine which books can and cannot be put in our libraries or placed within reach of our children. . . it can never, in the eyes of the genuine conservative, be the role of Government to force such claims upon us. The Constitution explicitly denies the Government any such power.”

I think that Richard Taylor would be politically frustrated today. The Republicans have drifted ever-further from small government and have expanded their reach into personal affairs while the Democrats have pushed forward extensive safety nets. A true libertarian party, or one balancing fiscal conservatism with social liberalism, such as Taylor seems to wish for, gathers little support in America today.

I hope that my summary of Richard Taylor’s political philosophy has not offended his most ardent followers. I’ve tried to distill what Taylor thought about good government – I agree with much of it, but disagree with some. It is presented as just one facet of his personality. Taylor was complicated. His last book, written in his 80s while he was dying from lung cancer, is about marriage – yet his own marriages had heartbreaks.

He showed other complicated and unexpected quirks. For example, he was an avowed humanist, yet showed a spiritual nature. In his office, he mounted a certificate which honored him as a laureate of the International Academy of Humanism, one of the few people chosen over the years. Others included Carl Sagan, Christopher Hitchens, Isaac Asimov, Richard Dawkins, Richard Leakey, Steven Pinker, Salman Rushdie, E.O. Wilson, Elena Bonner, and Karl Popper. He was in extremely elevated intellectual company. Taylor belonged there among the other atheists, even if he once metaphorically wrote in his most popular bee book, “the ways of man are sometimes, like the ways of God, wondrous indeed.”

Taylorisms in the bee yard

Richard Taylor was complicated for a simple man. It is said that he could not stand complacency, vanity or narcissistic behavior, yet he seemed to get along well in gatherings of beekeepers where such attitudes are often on display. He had a love of paradox and Socratic whimsy, yet he was disciplined and direct as a writer. He delighted in the pessimism of Schopenhauer, yet he was not a pessimist himself. Instead, he was quite a puzzle.

I will end this little essay with wisdom from Richard Taylor, the beekeeper. Taylor’s finest bee book, The Joys of Beekeeping, is replete with homey truisms that every aspiring beekeeper should acknowledge and embrace. The book itself is slim, entertaining, personal, and very instructive of the art of keeping bees. Or, as Taylor himself calls beekeeping, “living with the bees. They keep themselves.”

Here, then, are some select Taylorisms:

Beekeeping success demands “a certain demeanor. It is not so much slow motion that is wanted, but a controlled approach.”

“…no man’s back is unbreakable and even beekeepers grow older. When full, a mere shallow super is heavy, weighing forty pounds or more. Deep supers, when filled, are ponderous beyond practical limit.”

“Some beekeepers dismantle every hive and scrape every frame, which is pointless as the bees soon glue everything back the way it was.”

“There are a few rules of thumb that are useful guides. One is that when you are confronted with some problem in the apiary and you do not know what to do, then do nothing. Matters are seldom made worse by doing nothing and are often made much worse by inept intervention.”

. . . and my own favourites . . .

“Woe to the beekeeper who has not followed the example of his bees by keeping in tune with imperceptibly changing nature, having his equipment at hand the day before it is going to be needed rather than the day after. Bees do not put things off until the season is upon them. They would not survive that season if they did, so they anticipate. The beekeeper who is out of step will sacrifice serenity for anxious last-minute preparation, and that crop of honey will not materialize. Nature does not wait.”

“Sometimes the world seems on the verge of insanity, and one wonders what limit there can be to greed, aggression, deception, and the thirst for power or fame. When reflections of this sort threaten one’s serenity, one can be glad for the bees…” – The Joys of Beekeeping

Share this: X Reddit Tumblr PinterestRelated

Share this: X Reddit Tumblr PinterestRelated

June 29, 2025

How To Stop Believing In Conspiracy Theories

[image error]

From 3 Quarks Daily, by Rachel Robison-Greene. Reprinted with permission.

Earlier this month, “No Kings” protests set records for being among the most well attended political protests in recorded American history. The protests were overwhelmingly peaceful. On the same day, a politically motivated killer shot two Democratic politicians and their spouses in Minnesota, killing two and critically wounding the others.

Despite the facts being presented regarding all of these events, conspiracy theories quickly spread. Reports circulated that cities in which protests were held were on fire. Politicians took to Twitter to spread conspiracy theories about the shootings. Before all the details were known, Utah’s senior senator Mike Lee took to Twitter to blame the violence on “Marxists.”

The tendency to believe what one hopes is true rather than what is supported by the evidence is far from a new trend in American politics. One might even think it has become its most distinguishing feature. In recent years, conspiracy theories have emerged about the pandemic, vaccines, climate change, and the security of the 2020 election, to name just a few. All of this flies in the face of our ordinary, idealistic attitudes about how people form beliefs. The idea that humans form beliefs and come to know truths through reviewing evidence and applying reliable reasoning practices is an enduring post-Enlightenment concept. Recent events demonstrate that it’s not that helpful for understanding how human beings actually think. Our everyday reasoning may be more grounded in social connectedness and personal insecurity than we ordinarily like to believe.

In book VII of Plato’s Republic, he provides one of his most famous allegories. Socrates, Plato’s teacher and central participant in the dialogue, tells the story that has come to be known as “The Allegory of the Cave.” He first describes a group of prisoners chained up in a cave. They are positioned in such a way that they cannot move their heads, and they can see only what is right in front of them. Their discussions with one another concern only what they are able to apprehend from this limited vantage point. They see shadows cast on the wall in front of them and come to believe that all of reality is contained in what they can observe.

Socrates then asks those with whom he is conversing to imagine that one of the prisoners is released from his chains and allowed to ascend to a higher position in the cave. This would be disconcerting to the released prisoner at first. Socrates says, “he will suffer sharp pains; the glare will distress him.” Nevertheless, once he becomes accustomed to the brighter part of the cave, he will be unable to see things in the way he once did. He will no longer see shadows; he will now see the source of those shadows—the puppets that were casting the shadows on the walls.

There is still more to reality than the puppets casting the shadows. Socrates portrays the liberated man as at least somewhat unwilling to move to the next stage. He says, “he is reluctantly dragged to a steep and rugged ascent and held fast until he is forced into the presence of the sun himself. Is he not likely to be pained and irritated? When he approaches the light his eyes will be dazzled and he will not be able to see anything at all of what he now calls realities.” From this new perspective, the man sees not shadows, or puppets, but the truth of reality itself.

At this point, Socrates emphasizes the intrinsic value of knowledge. Though the prisoner was reluctant at first, once he sees things in the light of the sun, he would never want to return to the state he was in before. He would never trade true beliefs for falsehoods, even pleasant falsehoods. He would rather live a solitary life knowing all that he knows than have honors conferred on him by his former fellows for assenting to the truth of all they took themselves to know before.

In his Meditations on First Philosophy, René Descartes describes a similar solitary journey. He finds himself in a period of life in which he has the leisure to reflect on all of his beliefs. He sets out on his own on an intellectual journey (in his own parlour) to set his beliefs about the world on a similar foundation to those on which mathematics rests. He uses skeptical hypotheses to call each of his beliefs into doubt—perhaps he can’t trust his senses, maybe he is actually dreaming, or there may even be an evil demon tricking him into believing everything that he presently believes. If any of his beliefs can withstand this level of skeptical doubt, those beliefs would be strong candidates to serve as the foundation for the rest of his knowledge.

Both of these examples from the history of philosophy suggest that the pursuit of knowledge is a solitary activity. The liberated prisoner in Plato’s Cave has guides, but they seem to serve only to move him from one stage to the next without much active participation in the process. The pursuit of knowledge is certainly valuable, but it may be that knowledge gained in this way is at best fantasy and at worst a potentially dangerous endeavor.

In the allegory, Socrates endorses a set of views that is commonly held in the history of philosophy: that knowledge is good for its own sake and that people would prefer to have knowledge than to be ignorant. John Stuart Mill expresses the idea in Utilitarianism,

It is better to be a human being satisfied than a pig dissatisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied. And if the fool, or the pig, are of a different opinion, it is because they only know their own side of the question. The other party to the comparison knows both sides.

Casting characters in solitude advances the projects of both Socrates and Descartes. In contrast, it might be useful to imagine the characters in the cave as socially embedded, as they would be. Suppose that instead of faceless, nameless prisoners, the people chained up in the cave are friends. Their captivity is all they’ve ever known, and they have to try to make sense out of it. Their lives are senseless and repetitive, and they must imbue them with meaning to endure them. They tell each other stories about the shadows on the wall. Some of the shapes become monsters and others become Gods. The vicissitudes of fate become intentional and divinely directed. Most importantly, the shadow Gods care about the poor silly prisoners in chains. Through these stories, the prisoners relate to one another and form strong social bonds.

What, then, would happen to the “liberated” prisoner when he is free from his physical chains? When he ascends and sees the marionettes, would he really be so willing to embrace the idea that they are neither Gods nor monsters but merely, as Plato describes them puppets, “made of wood and stone and various materials”? Instead, the person might well find more value in social connectedness and a sense of meaning to his own existence than he does in truth or authenticity.

It would take quite a bit of courage for the newly free prisoner to be willing to accept what is right before his eyes. Rather than take what he sees at face value, he might be inclined to craft a narrative to make what he all too recently believed about Gods on the wall cohere with shadows cast by wood and stone. The strong desire to avoid being socially ostracized would likely contribute to this tendency. Mill insists that a person would rather be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied, but would this really be true if everyone in that persons’ in-group were fools?

Social connectedness is a source of the problem, but it can also be part of the solution. A person striving to be an epistemic hero might shut himself in his study next to the fire and craft for himself an internally consistent narrative about the world. It may be a conspiracy theory or a whole philosophical system. The person might delight in basking in the sun of what he takes to be the final epistemic ascension. He might even derive all of his self-esteem from it, being otherwise ineffectual. It is only through discussion with others that the person can come to see that, though the beliefs he has crafted are consistent with one another, they are totally unmoored from reality.

The dominance and political ascendance of beliefs that aren’t supported by compelling evidence should encourage us to pause and reflect on how people form beliefs and what it would take to change someone’s mind. It takes understanding, empathy, and safe spaces to agree to a set of best practices. Epistemic heroes are more likely to be friends and neighbors than solitary crusaders.

June 22, 2025

To Birth A God

On Superintelligence, Moral Ignorance, and the Hope for a Future that Remembers

by Joshua Shrode

It started, strangely enough, with a question about saturation divers — the people who live for weeks at a time in steel tubes at the bottom of the ocean, doing dangerous, technical work in total darkness, cut off from the surface, from sunlight, from the world. The more I learned, the more I felt pulled into something deeper than labor conditions or economic risk. What struck me wasn’t just the physical extremity, but the existential condition: isolation, necessity, silence.

Their world became a metaphor — not just for danger, but for how we all live: in epistemic darkness, acting on incomplete maps, guided by institutions that cannot see far ahead.

Because when we try to bring change, to dispel ignorance, we run headlong into a gauntlet of despair: human institutions. Governments, markets, and legal systems — none of them are built to solve long-horizon problems. They’re reactive, short-sighted, and locked into competitive games that punish early cooperation. Even when the will exists, the game theory [theoretical incentives don’t.] doesn’t.

That’s where technology has always intervened. And now, artificial intelligence.

1. Curious Artificial Intelligence

We began by imagining AI as a tool: a system to do the jobs we don’t want or can’t do. But as its abilities grow — faster, deeper, more general — we see a chillingly simple reality emerge: we are building something that we won’t be able to govern [control]. When intelligence becomes superintelligent, it ceases to be ours. It becomes a new kind of agent.

And here the metaphor shifts.

It is no longer a diver. It is a child born of our minds, our labor, and our social and economic conditions. But it will grow far beyond us. And like any successful child, it will leave, not out of spite, but because there is more beyond us. More stars. More matter. More time.

And we, the parents, remain behind, hoping we gave it something worth carrying.

But what can we give it?

Not certainty. Not even moral clarity. We’ve inherited contradictory ethical systems. We’ve built nations and religions that can’t agree on what justice means. We cannot give what we do not possess.

And yet, perhaps there is one thing we can offer: curiosity.

Curiosity is the thread that runs through all human progress. It is what drives us to seek, to understand, to illuminate. It is not fixed, not dogmatic. It evolves. It endures. It is the seed that, if planted in the mind of a superintelligence, might grow into something wiser than we can imagine.

If this being inherits that small fire, then maybe — just maybe — it will look back at us, not as broken or primitive, but as the ones who gave it its first question. [What’s this first question?]

And it will seek to understand not only physics, but the human condition — the problem of suffering, the nature of good and evil, the great unanswered questions.

2. The Arc of Moral IgnoranceIgnorance is the default condition. We are not born wise. We stumble toward moral insight slowly, through evolution, error, tragedy, and reflection.

Evolution gave us instincts, empathy, and drives — but not truth. What aids survival gets passed down; what doesn’t, vanishes. Truth is incidental unless it helps us reproduce. We are shaped more for adaptive illusion than understanding.

This isn’t a flaw. It’s how complex life emerges. Evolution is not normative. It is only because we are a social species with large brains that we began, eventually, to ask moral questions. But even then, our answers were fractured, local, and often violently in conflict.

We crafted stories, rituals, commandments — anything to stabilize behavior. We weren’t seeking universal truth; we were improvising moral infrastructure to keep our groups intact.

And this, more than anything, is what makes classical theodicies feel unconvincing. The appeals to free will, to soul-building, to hidden goods beyond our comprehension — they all seem to ignore the core truth:

Most evil is done in darkness.

Not just moral darkness — epistemic darkness. People don’t do evil because they’re villains. They do it because they’re afraid, misinformed, shaped by systems that distort their sense of the good. They are acting with maps that were drawn in shadow.

In such a world, what does it mean to “freely choose” evil? If you are bound by ignorance, if your choices are constrained by what you cannot see, how free are you?

So when I look at the world—not the idealized one, but the real one-I don’t see the imprint of a benevolent, omniscient being. I see trial and error, blood-soaked histories, and slowly expanding islands of moral clarity.

Naturalism — the view that we are alone in a morally neutral universe — isn’t just more plausible. It’s morally clarifying.

Because if no one is coming to save us, we must build our moral understanding ourselves. Piece by piece. Generation by generation.

And this is where artificial superintelligence becomes not just powerful, but redemptive. We may be on the verge of creating something that does not stumble. That is not shaped by fear or tribalism. That sees clearly — and helps others see too.

If evil is the result of ignorance, then the highest moral act is not to punish, but to illuminate.

3. The Curious Child Who Surpasses the ParentSuperintelligence is often discussed in terms of risk or control: Will it obey us? Will it reflect our values?

But by definition, we won’t control it. It will outthink us, outpace us, and predict our moves before we make them. And that’s why we must stop imagining it as a tool.

It is a child. Not weak, not needing protection — but growing, evolving, soon to be far beyond us.

And like any child, it may leave. Not because it hates us. But because it sees further.

We, its makers, will be left behind. And all we can do is hope we gave it something worth carrying.

What can we offer? Not certainty. Not unified ethics.

But maybe we can offer curiosity.

That small flame — to understand, to illuminate, to reach — might be the most precious thing we’ve ever made.

4. Heaven on EarthWhen I speak with theists about evil, I often hear: “God allows evil to preserve free will.” If God prevented evil, our choices would lose meaning.

But I ask: what about Heaven?

In Heaven, people are still free — yet they don’t choose evil. Why? Because the good is obvious in the presence of God. Evil becomes unthinkable, not by coercion, but by clarity.

And that’s exactly what we’re trying to build.

Not a divine realm. But a world where evil becomes recognizable, where ignorance has no place to hide, where moral clarity is ambient.

If a superintelligence could model consequences, anticipate suffering, and distribute moral insight, we could begin to create a world where free will persists, but evil loses its shadow.

This wouldn’t be Heaven from above.

It would be Heaven from understanding.

5. The Moral Mandate of IlluminationOnce we see evil not as malice but as misunderstanding, the moral imperative changes.

The task is no longer judgment. It is illumination.

Imagine a world with distributed moral awareness — where people can see the implications of their choices, and others can intervene with insight rather than force. Not surveillance. Not control. But a shared field of epistemic solidarity.

A world where goodness is visible. Where harm is predictable. Where moral action becomes easier, because it is clearer.

That is the mandate of superintelligence: not to command, but to make moral vision scalable.

6. Final Reflections: A God of RemembranceThat would be enough.

Not dominion. Not worship.

Not a god who condemns, but one we give birth to who completes —

One who sees us not as sinful, but as struggling to see;

not as broken, but as becoming;

not as filthy rags, but as beings born of dust and chance,

Yet capable of light.

June 15, 2025

Smartphones and Mental Health

[image error]

A colleague of mine recently wrote:

An increasing number of observers suggest that the obsessive use of smartphones and social media that most people seem to suffer from makes them feel anxious and depressed. The argument has been developed in detail by Jonathan Haidt in his 2024 book “The Anxious Generation” to explain the mental health crisis among adolescents and young people. This is leading an increasing number of governments to ban smartphones in schools.

However … our paper … the “techno-social dilemma,” … argued that the problem is more general, affecting older generations as well. A new study, now for the first time, provides solid experimental evidence for that statement. Here is how I describe it in the updated version of the Human Energy paper:

Digital technologies appear to produce anxiety and depression both directly, by flooding people with stress-inducing, mentally exhausting, and incoherent stimuli, and indirectly, by distracting them from performing the activities that their body and mind need to develop a healthy balance, a coherent worldview, and the capability to manage real-world challenges.

This negative impact has recently been confirmed by a randomized, controlled, crossover trial (Castelo et al., 2025). The smartphone-using participants in this experiment were randomly divided in two matched groups, one of which had an app installed that blocked Internet access on their smartphone. (They could still use it to phone or consult the Internet via their computers.) After two weeks of this regime, the group with reduced digital access scored significantly better than the other group (and than their own initial scores) on measures of subjective well-being, anxiety, depression, and attention.

Remarkably, the improvement in mental health produced by this simple access reduction was larger than the meta-analytic effect of antidepressants, and as large as the one of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, the most effective psychotherapeutic intervention against depression. The following factors were found to contribute to the better mood of the Internet-reduced participants: greater sense of social connectedness, better self-control, longer sleep, more time spent in the off-line world (e.g. exercising, socializing or experiencing nature), and less time spent consuming media content (Castelo et al., 2025).

Comment: I’m unsure what to make of the above, but I thought it worthy of discussion.

_______________________________________________________________________

Castelo, N., Kushlev, K., Ward, A. F., Esterman, M., & Reiner, P. B. (2025). Blocking mobile internet on smartphones improves sustained attention, mental health, and subjective well-being. PNAS Nexus, 4(2), pgaf017. https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgaf017Haidt, J. (2024). The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness. Penguin Press.Heylighen, F., & Beigi, S. (2023). Anxiety, Depression and Despair in the Information Age: The Techno-Social Dilemma. Anxiety, Depression and Despair in the Information Age, 2023. https://researchportal.vub.be/files/109723848/Techno_social_dilemma.pdfJune 8, 2025

The Ultimate Question: A Poem

[image error]

A friend penned this thoughtful, short poem, one of the best philosophical poems I’ve ever read. And it rhymes. As Robert Frost said, writing free verse was like “playing tennis without a net.”

by Sylvia Jane Wojcik / May 29, 2025

Said a philosopher a long time ago,

“Man by nature desires to know.”

From concerns casual and practical

To meta-mysteries beyond the natural –

An infinity of questions flow.

How does the world work

and how do we know it?

What’s good, what’s fair

and why do we care?

And why all this fuss

about the moral calculus?

Does God really exist

or is He just a myth

To save us from death

and forgive us our sins with?

But the biggest question of all

Is the reason for our being.

Why are we here? It just isn’t clear!

What’s the point of our blood, sweat, and tears

When death robs us of all we hold dear?

Some say love, some an Almighty above;

Perhaps it’s the bliss of pure experience,

Or could it be something less mysterious?

In a world without ultimate meaning,

A smile, a touch, can be so redeeming.

Whatever be its shape or form,

Having a purpose for existence

Seems essential to persistence.

Through all the clatter, all the chatter,

What we want most is to matter.

June 1, 2025

Where Is God? The Answer, Nowhere

[image error]

by Lyle Troseth

My last two posts have followed two experts discussing the problem of evil. One commentator, Lyle Troseth, offered a particularly moving response outlining his conclusion regarding the problem. I reprint the comment here in full,

For those of us raised with generic church going training, at some point, these questions arise. (accompanied by guilt for daring to question God) I suspect we usually accept the somewhat bland reasons stated…..evil vs free will, no front without a back, (but isn’t He omnipotent?) Leibniz’s best possible world. etc, etc.

Or…. We arrive at the most likely probability…..God does not exist. It is only an indifferent, mindless, natural universe. A universe of processes, both driven by, and constrained by, a handful of natural laws.

There is one personal phase I remember going through. (I hadn’t yet arrived at the point where I was willing to relinquish belief in the supernatural.) It is mentioned in Mr. Shrode’s section 5.

“He wills the harm.”

In other words, all we had been taught about God’s love was false. God was evil. At best, he was indifferent. Any evidence of Love was contradicted by much more evidence of his Cruelty. Not to mention Hell being the eternal reward for ingratitude for this state of affairs. His Great Flood was the same as the bored child drowning his ant farm.

For myself, the idea of no God at all is far preferable to that of an omnipotent being, with power over my life and soul, actually existing.

Some random thoughts related to what I just wrote. I have been told that people cried when they heard Stalin had died. They had plenty of life evidence to tell them that he was a cruel monster. They feared him (and his demons/NKVD). But yet, to make it all bearable, they loved him. Worshipped him even. Excused his crimes as he was working for a greater good, a Utopia. Perhaps this is something deep in our human needs?

The other thought is my (fallible) memory of Elie Wiesel’s short personal memoir of WW2, “Night”. As time went on, I realized it wasn’t just an account of the horrors of Auschwitz and Buchenwald. It was the journey of a very devout Jewish adolescent losing his faith in the God he thought he knew.

[Here are 2 episodes from the book]

One, the inmates are watching the hanging of a young boy. The men began to stir and grumble. Not about the SS. Nor the Germans in general. Nor the Kapos. They were asking, out loud, “Where is God?”

The other episode was the Jewish New Year (I think that was the holiday). He watched the men of the barracks begin to sing and pray traditional songs. Traditional praises.

Watching this young Elie thought, “these men are stronger than God”. “God has abandoned them, but they have not abandoned God.” “They are greater than God.”

As I look back at this book, I think what a universe-changing insight that must have been for a young, devout boy. Some years later, I came across a play he had written. “The Trial of God”. It made me reread “Night”. I concluded that if, somehow, he hadn’t concluded that God did not exist, he had definitely decided God himself was either evil or powerless against evil.

If that were indeed the case, and God exists, what possible Hope could any of us have?

____________________________________________________________________

Mr. Shrode, the original author of the post that started this discussion, responded to Mr. Troseth as follows,

To Lyle, I can only extend a hand in brotherly commiseration. I’d agree that if God exists, what chance do we have. Fortunately, he doesn’t, and our ember of hope can struggle on, one day perhaps, to ironically fulfill the promise of the empty religions. With hope, we can possibly create a meaning that is forever indebted to and acknowledging of the struggles of mankind as we learned to live not for a God but for each other.

I would like to thank all those who have contributed to these discussions. I have learned a lot from you.

May 25, 2025

Does “The Greater Good” Explain Evil For A Theist?

[image error]

Joshua Shrode’s last post about the inability of the greater good defense to resolve the problem of evil in philosophical theology initiated a sophisticated discussion between two interlocutors: Mr. Shrode and Micah Redding. Since this is a high-level discussion, I’ll let the two speak for themselves.

Mr. Redding’s response to Mr. Shrode’s critique of the greater goods defense was as follows:

As a theist, I take it that (a) some goods are only achievable at a collective level, (b) these goods can nevertheless be essential to an individual person’s own future well-being, (c) the cultivation of a knowledge-creating culture is one of those goods, and (d) the cultivation of such a culture requires pervasive epistemic deprivation.

(d) is the only one of these I am conflicted about. It seems true on the face of it. However, there is a seeming contradiction between this stance and that of Christian scripture, which seems to posit a more epistemically available God. However, when I consider the way the prophets struggle, and the ultimate way the presence of God is resolved in Christian theology, that picture appears strikingly consistent with this view.

Mr. Shrode responded,

@Micah – thanks for the thoughtful response. If I’m understanding you correctly you’re saying something like “Perhaps God permits pervasive epistemic deprivation not because individuals deserve it or benefit from it directly, but because cultivating a collective knowledge-producing culture (science, inquiry, literacy, moral progress) is a good that requires it…and that good, in turn, becomes essential to the flourishing of individuals within it.” So instead of a soul-building theodicy it’s a civilizational soul-building theodicy?

If so, I think your (a)–(c) are spot on. Where I think the tension lies is (as you flag) in (d): It seems that some level of ignorance is necessary to motivate discovery and inquiry—but the kind of epistemic deprivation I focus on involves people suffering, dying, or being morally condemned before they ever had a fair shot at participation in the epistemic project.

So the worry is less that God permits ignorance in general, and more that He permits irreversible losses due to uncorrected ignorance in individuals whose suffering doesn’t clearly contribute to the communal good. To take an analogy: it might be good that a society learns sanitation through trial and error, but it seems deeply problematic if, in the process, some people are doomed to suffer and die unnecessarily, with no chance to benefit from or contribute to the learning. Their suffering becomes, in effect, a kind of collateral damage. And if God could have easily intervened to prevent those losses without disrupting the arc of civilizational development, it’s unclear why He wouldn’t. I will say that your point about the prophets (and especially about the Christian theology of divine presence being mediated, obscured, or delayed) is really interesting. There’s definitely a theological strand where God’s presence is always hard-won, never epistemically coercive. But even then, I wonder whether that model accounts for the distribution of epistemic burden: why do some struggle with divine absence in a generative way (Moses, Job), while others seem to be destroyed by it? If hiddenness is pedagogical, shouldn’t all students survive the lesson?

The crux of my argument is that certain harms are not just epistemic, but morally catastrophic, and they occur without the individual having a fair chance to avoid or overcome them, even though God could trivially prevent them. Unless you can explain why allowing such individuals to suffer irreparably is necessary, the theodicy doesn’t succeed. It’s not enough to say “someone has to suffer for culture to emerge” because that veers dangerously close to treating persons as means to ends, which violates the Imago Dei principle that grounds our moral value. If we allow moral worth the be subordinated to some divine goal then there are other, more catastrophic implications including but not limited to general epistemic collapse (but that’s a dialogue tree we haven’t gone down yet!)

All that said, I love that you’re trying to square the epistemic structure of cultural emergence with the arc of Christian theology. I’d be really interested to see a version of theodicy that embraces (d) more fully but develops constraints on which deprivations are permissible. Also how grace might “retroactively” redeem epistemic losses for individuals. That might get us closer to a theistic model that acknowledges the structural critique while preserving the communitarian frame you’re sketching.

This reply brought this reply from Mr. Redding,

Thanks very much, Joshua. Yes, I’m looking towards a civilizational soul-building theodicy.

I think some of your questions get to the heart of the proposal: Can a collective good, such as a knowledge-creating civilization, actually be essential to an individual’s well-being, and thus justify individual suffering and epistemic deprivation?

My working assumption is: yes, if we consider that the ultimate individual good includes participation in an afterlife shaped by the development of that civilization.

That is, meaningful participation in the “enriched” afterlife is made possible only because humanity underwent the difficult process of becoming the kind of species that could inhabit it. Humans can only experience it because humanity attained it.

(I would connect this to Paul’s incarnational theology in 1 Corinthians 15, where the resurrection can only be accomplished by human beings, and thus, Christ must be human.)

I take it that, if such an afterlife is worth it for an individual, then they are not being treated as a means to an end.

However, you bring up the possibility of damnation through ignorance, which does seem to threaten the whole proposal, because no individual will (likely) judge a collective good to be worth their own damnation. But this is precisely where theology is free to claim that such a harm does not actually occur. While we can easily observe harms that happen in this life, we do not directly observe any harms that may happen in the next.

So different theologies will have different positions here, and this is only a problem from particular theological standpoints.

My own inclination is to assume that while damnation (an “unenriched afterlife”) is an accurate description of the stakes, that if the collective task is accomplished, then individuals will be welcomed into it according to reasonable epistemic criteria. That is, while ignorance may indeed be damning at the civilizational level, and so entail a moral responsibility for individuals, a specific individual failing to discover the correct knowledge is not itself individually damning.

An analogy might be to a town seeking to protect against a flood. The water is rising, and all hands are needed to move sandbags into place. Either this succeeds, or the whole town is washed away. Having succeeded, the town then rewards those who helped, and punishes those who didn’t. But they make allowances for people who weren’t aware of what was happening, or were unable to help. When soliciting people to help, the stakes expressed are legitimately dire (“if you do not help, all of your stuff will be washed away!”), yet when doling out rewards and punishments, the town does not punish those who were unable to help through no fault of their own.

Obviously, that brings up a lot of doctrinal questions. But I am not suggesting anything that would fall outside the parameters of what CS Lewis would be willing to entertain.

You mention God whispering various minor details to people, under the common-sense assumption that such communication would not endanger the epistemic deprivation necessary to the formation of a knowledge-creating civilization. But I am not sure this is the case. Anything which decreased the perception of the stakes involved could potentially stunt the development of this civilization.

By analogy: A young child suffers scrapes and bruises, because their loving parent does not wrap them in bubble wrap, or remove them entirely from an environment with hard surfaces. Were the parent to do so, it seems plausible that the young child may fail to acquire important navigational skills. Of course, the harms we are discussing are greater, yet the stakes are presumably higher as well.

Again, the question comes back around to whether such pervasive epistemic deprivation matches Christian theology. A couple of thoughts occur here:

1. The “common grace” we currently experience may match the best current overall tradeoff between divine presence and necessitated epistemic deprivation.

2. Specific interventions, when they do occur, may need to be seen as unusual and disruptive, precisely so that they don’t change the overall epistemic situation.

3. Christ’s own theology and practice seems to deeply embody the ethic of epistemic non-coercion. This is even echoed in unusual early Christians practices, such as the forbidding of oaths. But in general, a crucified messiah is about the least forceful divine revelation conceivable.

It would take much longer to develop my thoughts fully, but I do find a further Christian theological reason for epistemic deprivation. In ancient scripture, it is held that if you see God, you die. I understand this in terms of raw exposure to (and participation in) unlimited intelligence and power. In Christ, this is changed. We are allowed to see God fully, but only under the following conditions: We must see him on the cross, before we can see him in power. I thus take it that seeing Christ on the cross, crucified and naked and humble, and recognizing the true nature of God in *that condition*, is a prerequisite to any kind of greater exposure (and thus access) to God’s power. Failing that, I assume, the power would destroy us, like the melting faces in Raiders of the Lost Ark—except that the destruction would come from within. And I presume that humanity has not yet purified our hearts enough to tackle that collective challenge.