John G. Messerly's Blog, page 5

January 5, 2025

The Philosophy of Albert Caraco

[image error]

My last post was about the philosophical pessimist Emil Cioran. Since then I have discovered another pessimistic writer, one that I had never heard of before—Albert Caraco. Caraco (1919 – 1971) was a French-Uruguayan philosopher, writer, essayist and poet of Turkish Jewish descent. He is known for his two major works, Post Mortem (1968) and posthumously published Breviary of Chaos (1982).

Caraco was born Istanbul on July 8, 1919 to a Jewish family. His family relocated to Vienna, Prague and later in Berlin, before settling in Paris. In 1939 Caraco and his family fled to South America due to Nazi threat and approaching World War II. In 1946, Caraco returned to Paris, where he spent the rest of his life devoting himself to writing. His mother’s death in 1969, widely documented in his work, Post Mortem, had a negative effect on his mental state and on September 7, 1971, following his father’s death, he committed suicide.

I have read none of Caraco’s works as they have not been translated to English. However, I have been able to piece together a bit of his philosophy by reading the very few English commentaries on his work that I have discovered, the best and most complete of which can be found here. Here are some of the highlights from that commentary:

His aim is .. to return the universe to it’s origin: chaos, absolute indifference, nothingness … He refused religions … any form of trascendence, any form of order, he was focused on catastrophes, death, corruption and decay and embraced a form of gnostic nihilism…

Caraco is an unusual and hard to classify thinker who wrote aphorisms and

dialogues. But his central idea (as best as I can glean) focuses on the

indifference of the universe towards all the human life and values. He wrote:

…I have been positioning myself in this nothing in which I feel

truly myself for years, and I occupy myself with the costant exercise of

unknotting my ego, the game doesn’t come without charm, and after all,

it does not cost a thing, maybe it costs only those smoky ideologies

which I am happy to lose …

There are of course many other themes in Caraco’s work: the centrality of chaos, the harm of being born, the rejection of progress and more. Unsurprisingly, he was an atheist who saw religion as disgraceful:

“if there is a God, chaos and death will appear among it’s

attributes, if God doesn’t exist, it changes nothing, for chaos and

death will be self-sufficient until the end of time.It doesn’t matter

what it’s praised, we are all victims of caducity and dissolution, it

doesn’t matter what is adored because this can’t help in avoiding

anything, the good and the bad have only one common destiny, a common

abyss which hosts saints and monsters, the idea of right and wrong is

nothing but a delirium, at which we cling for convenience.”

As I stated when writing about Cioran, I find it hard to analyze these pessimistic philosophers. On the one hand, I believe many people are overly optimistic about life and never really come to terms with how horrible life is and has been for billions of people. On the other hand, we cling tenaciously to life, perhaps from instinct but maybe also because we consider oblivion so undesirable. Moreover, its hard to escape the conclusion that one’s philosophy is mostly a reflection of one’s personality, in which case your philosophy describes subjective rather than objective reality. I’ll end with a relevant quote from William James

These, then, are my last words to you: Be not afraid of life. Believe that life is worth living, and your belief will help create the fact. The “scientific proof” that you are right may not be clear before the day of judgment … is reached. But the faithful fighters of this hour, or the beings that then and there will represent them, may then turn to the faint-hearted, who here decline to go on, with words like those with which Henry IV greeted the tardy Crillon after a great victory had been gained: “Hang yourself, brave Crillon! We fought at Arques, and you were not there.

__________________________________________________________________________

The above obviously leaves a lot unsaid about Caraco’s thought. For more see the previously mentioned commentary or watch the brief video below.

December 29, 2024

Emil Cioran: A Philosophical Pessimist

Emil Cioran (8 April 1911 – 20 June 1995) was a Romanian philosopher, aphorist and essayist. His work has been noted for its pervasive philosophical pessimism, frequently engaged with issues of suffering, decay, and nihilism. In 1937, Cioran moved to Paris, where he lived for the rest of his life in seclusion with his partner, Simone Boué, until his death in 1995.

Cioran expressed a little interest in conventional philosophy in his early youth, dismissing abstract speculation and logical argumentation in favor of personal reflection and passionate lyricism. Aphorisms make up a large portion of Cioran’s bibliography, and some of his books, such as The Trouble with Being Born are composed entirely of aphorisms.

Philosophical pessimism characterizes all of his works which often depict an atmosphere of torment and are preoccupied with the problems of death and suffering. All of this despite the fact that Cioran was considered a happy, cheerful man to those who knew him best. He was attracted to the idea of suicide, an idea he fully explored in On the Heights of Despair. He revisits suicide in depth in The New Gods, which contains a section of aphorisms devoted to the subject. The theme of human alienation is formulated by a young Cioran in On the Heights of Despair as follows: “Is it possible that existence is our exile and nothingness our home?”

Philosophical pessimism is hard to evaluate. For instance, how can we adequately access the question “would it have been better not to have been born?” It may indeed be better if nothing had ever existed—assuming nothingness is even possible—but I don’t know how to evaluate that claim. It may also be that something like the blind will in Schopenhauer’s philosophy drives us and reason actually recommends putting an end to consciousness. But again I just don’t know how to assess claims about whether life is or is not preferable to nothingness. (The contemporary David Benatar, have written persausively that we would be better off never having been born.)

What I can say is that presently I enjoy my life, at least most of the time. But then I’m a privileged white male living in a first-world country with a roof over my head, food in my refrigerator, access to quality medical care, in relatively good health, and who was the recipient of an extraordinary education. I certainly understand that for many others life isn’t worth living and this fills me with irredeemable sadness. I wish I could say more.

As for a more detailed video about Cioran I recommend the following,

December 22, 2024

Resistance to Change in Sports

[image error]

Every now and then you have to forget serious thought and have fun. This is a story for American football season.

Resistance to change is everywhere—even in sports. Think of the slow embrace of using stats (analytics) or changing the rules in professional sports. Giving up and out in baseball by bunting a runner to second base was once the orthodox move in professional baseball. Or consider another example from professional football. I grew up in St. Louis and our NFL team (1960-1987) then was the St. Louis (now Arizona) Cardinals. From 1963 to 1978 our placekicker was Jim Bakken.

[image error]Bakken was a 4-time pro-bowler and 2-time first-team all-pro, one of the best kickers of his era. ( You can see all his stats here.) Note that Bakken made only 63% of his field goals for his career from all distances; about 43% from 40-49 yards; and was 1 for 21 from 50 yards or more. Bakken also missed 19 extra points in his career in 553 attempts. (This is when an extra point was from about 19 yards.) Compare this to stats for kickers in the NFL last year. Today NFL kickers rarely miss field goals and even make the vast majority of their kicks from over 50 yards.

Kickers today are better for many reasons, but mostly because they kick the ball with their instep (soccer style.) Bakken, like most kickers of his era, kicked with his toe! When the first soccer-style kickers came along, they were viewed with suspicion. Who would kick a ball with their instep instead of their toe? Wow, that’s radical! That’s what I mean, resistance to change. Humans prefer stasis to dynamism; they are always stuck in the past.

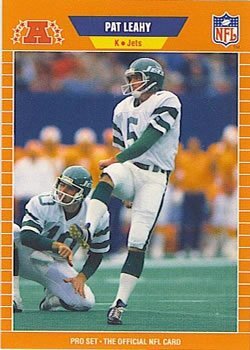

Now to finish my story. In 1974 the St. Louis (football) Cardinals gave a tryout to a star soccer player from St. Louis University named Pat Leahy. Naturally, the Cardinals kept Bakken and cut Leahy—heck Leahy didn’t kick with his toe! Leahy went on to become the kicker for the Jets from 1974 to 1991.

Leahy finished his career 3rd on the all-time scoring list in the NFL with 1470 points. (He has since been passed by multiple players.) Leahy would be a terrible kicker by today’s standards—probably couldn’t even be a major college kicker—but he was a LOT better than Bakken. So why did the Cardinals chose a toe over a whole foot?

Leahy finished his career 3rd on the all-time scoring list in the NFL with 1470 points. (He has since been passed by multiple players.) Leahy would be a terrible kicker by today’s standards—probably couldn’t even be a major college kicker—but he was a LOT better than Bakken. So why did the Cardinals chose a toe over a whole foot?

Well kicking a football with your instep was just thought to be weird, too non-traditional, whereas kicking inaccurately with your toe was then thought normal. That’s just what we do, we use a little pointed toe, especially the one adjacent to your big toe, the one that sticks out the farthest on some people. Why would you use your much-wider whole foot? That just wasn’t traditional.

That’s what I mean, resistance to change. It’s everywhere.

And, on a serious note, live on earth will only survive if we adapt and change.

December 15, 2024

Philosophical Implications of the Size and Age of the Uni(Multi)verse

The size (and age) of the universe induces within me both awe and a feeling of incredible insignificance. Here’s what I wrote about the universe some years ago,

Our galaxy contains more than 100 to 400 billion stars and there are more than 100 billion galaxies in the observable universe. All this is in a observable universe that is about 93 billion light-years across and almost 14 billion years old. (The universe is larger than its age because it has been continuously expanding since the Big Bang, meaning the space between objects is constantly increasing, allowing the observable universe to be much larger than the distance light could travel in the time the universe has existed…)

And there may be an infinite number of universes or the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics may be true or we may be living in a computer simulation or … Needless to say, all of this is largely incomprehensible to me.

Now some philosophers have dismissed our worries about the universe’s size. Thomas Nagel wrote,

Consider next the argument that our lives are absurd because we live in a tiny speck of a vast cosmos, or in a small sliver of time. Nagel argues that neither of these concerns makes life absurd. This is obvious because even if we were immortal or large enough to fill the universe, this would not change the fact that our lives might be absurd.

I agree that being immortal or larger (by being able to travel to and experience much of the universe) doesn’t assure us that life is meaningless or insignificant but they would go a long way to eliminating my feelings of dread. Being so small, essentially invisible, lends itself to this feeling of unimportance. It’s not like we are the center of the universe as we thought in medieval times. In fact our entire galaxy, immense beyond comprehension is itself essentially invisible from a cosmic perspective.

I find these thought devastating. I remember thinking of my little world as a child as being so central, so big, so important. Yet I find that in the vastness of space and time it’s hard to maintain that illusion. What of my parents and teacher and what they taught me on this infintisimally small speck of earth? What of my relationships, my hopes, my fears? How can anything anyone does be that important? Just watch one of these videos and let the size (much less the age) of the universe sink in. We are smaller to the universe than a subatomic particle is to use. Scroll out as the earth, solar system, galaxy, and local group disappear. Doesn’t it seem we disapper too?

And if we add the age and trillions of years of future to our consideration, what difference does it make what any of us do and think? Yes, its worse if we have psychopathic people rather than good people running around. And yes I try to live as best as I can, enjoy myself, help who I can, etc. But there is something extraordinarily disquieting about the size and age of reality. Maybe in the end we just have to take consolation in this fact. No more worries about all the stupid things we worry about.

Nonetheless there are always counter arguments here. Would I feel better if the entire universe was the size of the earth? Would this even make sense since you can always ask what is beyond the age. Would I be comforted if the medieval view that the earth is the center of the the cosmos surrounded by the stars and the heavens beyond them? Maybe. But then again perhaps the universe has to be infinite in space and time.I just don’t know.

Still watching these videos fills me with feelings I don’t even know how to put properly into words. What I feel is that the universe science has revealed to us is inconceivable to me and all talk of explanation much less salvation is a fool’s game.

Here’s another great video with a slightly different take,

December 8, 2024

When Should I Argue?

[image error]

A reader made this insightful comment on my (long ago) post: “On Belief and Skepticism“:

I empathize with this exact scenario. I too am a dedicated skeptic, but find it difficult sometimes to “disagree without being disagreeable.” Many people I disagree with most fundamentally are the ones I love most profoundly. Do you maintain close relationships with people holding drastically different beliefs? It’s hard to separate the person from the ideas they hold especially when there is so much vested emotionally in those ideas. I hate the idea of “agreeing to disagree.” I’m not going to dance around the issue; We are adults and honesty is important. How do you approach these relationships?

Here is my reply.

As far as “disagree without being disagreeable” I suppose that’s a matter of attitude. You can disagree in a disagreeable manner, but you can also disagree in a non-disagreeable way. I don’t think you can disagree in an agreeable manner since that would imply you were agreeing. So it’s best to voice your disagreement with the ideas expressed, but not personally attack the person who expressed those ideas.

I do think that we can have relationships with people who hold different views. There are people in the most intimate lifelong relationships who disagree about politics, religion and other subjects. Still, it’s easier to have good relationships with people whose values and beliefs you mostly share, and marriages are more successful between persons who have similar personalities, as far as I know.

Yet it’s hard to separate people from their ideas. If I’m progressive and someone is a fascist, or if I’m an agnostic and someone is a biblical literalist, that’s very hard to overcome. In such cases, it would be hard to say: “she is ok, but she is also insane because she’s a biblical literalist and that involves holding contradictory ideas simultaneously as well as believing things that conflict with well-established scientific truths.” Yes, people certainly have a lot invested emotionally in their ideas, which in large part explains why they are so resistant to changing them, even in the face of good reasons to do so.

I think the best you can do is to decide when it’s worth it to enter into a polemic. For me, that’s when I feel the truth is being distorted, and the issue is important. For example, if someone says that Asians are inherently inferior to my racial group and we should kill them all, then that’s something to challenge. If they say that it is generally colder in Florida than in Minnesota then it probably isn’t such a big deal to let their ignorance slide.

Now suppose I encounter a gravitational, germ, or evolutionary theory denier. In such cases, I should be willing to enter into a polemic because any educated person knows these are well-established scientific truths. Furthermore, to deny them might entail someones jumping off a building thinking they’ll fly; not washing their hands before handling food; or counting on last year’s flu shot to work this year. (Viruses evolve quickly.) Of course, you probably won’t change their minds, since so many persons are willfully ignorant.

Now suppose you encounter a climate change denier. You tell them that the intergovernmental panel of climate scientists now claim with 98% certainty that humans are the cause of global climate change. But then you probably have to leave it at that. The fact that they are mistaken about climate change (and arrogant to think they know more about the subject than the world’s experts), probably doesn’t matter that much. True you might convince them not to vote for a climate change denier, but one vote isn’t that significant and their mistaken view is unlikely to change anyway.

Of course, if someone is getting upset or violent then you should agree with anything they say. After all Galileo recanted the Copernican view of the solar system in the face of the Catholic Church’s threatening his life. (Bruno had been recently burned at the stake for advocating such a view.) But among friends—and if someone is willing to kill you over your beliefs they shouldn’t be your friend—I think you just have to decide how serious the issue is and take each case on an individual basis.

I will say this; as I get older I let a lot more slide than when I was young. And that’s because you rarely change people’s minds—people are just emotionally attached to their ideas. After 30 years of university teaching, I can affirm that few people ever change their minds.

But when someone says: “let’s start another war,” or “let’s deny people health care,” well those claims hurt people. And if that doesn’t matter then what does? In such cases, you should probably enter into a polemic.

November 29, 2024

The Pale Blue Dot

Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space

The astronomer Carl Sagan is one of my intellectual heroes, and one of the great secularists of the twentieth century. Almost ten years ago, I posted this video of his—one of the most moving short videos I’ve ever seen. Its message so resonates in our troubled times.

In 1989, after both Voyager spacecraft had passed Neptune and Pluto, Sagan wanted a last picture of Earth from “a hundred thousand times” as far away as the famous shots of Earth taken by the Apollo astronauts. No photo has ever put the human condition in better perspective; it is worth seeing and hearing at least once a year for the rest of one’s life. Thank you, Carl Sagan.

The text:

“Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every “superstar,” every “supreme leader,” every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there-on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.

The Earth is a very small stage in a vast cosmic arena. Think of the endless cruelties visited by the inhabitants of one corner of this pixel on the scarcely distinguishable inhabitants of some other corner, how frequent their misunderstandings, how eager they are to kill one another, how fervent their hatreds. Think of the rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors so that, in glory and triumph, they could become the momentary masters of a fraction of a dot.

Our posturings, our imagined self-importance, the delusion that we have some privileged position in the Universe, are challenged by this point of pale light. Our planet is a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark. In our obscurity, in all this vastness, there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves.

The Earth is the only world known so far to harbor life. There is nowhere else, at least in the near future, to which our species could migrate. Visit, yes. Settle, not yet. Like it or not, for the moment the Earth is where we make our stand.

It has been said that astronomy is a humbling and character-building experience. There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world. To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another, and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we’ve ever known.”

November 22, 2024

Superintelligence and The End of Humanity

[image error]

Preeminent scientists are warning about serious threats to human life in the not-distant future, including climate change and superintelligent computers. Most people don’t care.

Stephan Hawking, along with MIT physics professor Max Tegmark, Nobel laureate Frank Wilczek, and Berkeley computer science professor Stuart Russell ran a terrifying op-ed over ten years ago in The Huffington Post under the staid headline “Transcending Complacency on Superintelligent Machines.” It was loosely tied to the Johnny Depp sci-fi thriller Transcendence, so that’s what’s happening there. “It’s tempting to dismiss the notion of highly intelligent machines as mere science fiction,” they write. “But this would be a mistake, and potentially our worst mistake in history.”

And then, probably because it somehow didn’t get much attention, the exact piece ran again last week in The Independent, which went a little further with the headline: “Transcendence Looks at the Implications of Artificial Intelligence—but Are We Taking A.I. Seriously Enough?” Ah, splendid. Provocative, engaging, not sensational. But really what these preeminent scientists go on to say is not notsensational.

“An explosive transition is possible,” they continue, warning of a time when particles can be arranged in ways that perform more advanced computations than the human brain. “As Irving Good realized in 1965, machines with superhuman intelligence could repeatedly improve their design even further, triggering what Vernor Vinge called a ‘singularity.’ “Get out of here. I have a hundred thousand things I am concerned about at this exact moment. Do I seriously need to add to that a singularity?” Experts are surely doing everything possible to ensure the best outcome, right?” they go on. “Wrong. If a superior alien civilization sent us a message saying, ‘We’ll arrive in a few decades,’ would we just reply, ‘Okay, call us when you get here–we’ll leave the lights on?’ Probably not. But this is more or less what is happening with A.I.”

In a lecture he gave recently at Oxford, Tegmark named five “cosmocalypse scenarios” that will end humanity. But they are all 10 billion to 100 billion years from now. They are dense and theoretical; extremely difficult to conceptualize. The Big Chill involves dark energy. Death Bubbles involve space freezing and expanding outward at the speed of light, eliminating everything in its path. There’s also the Big Snap, the Big Crunch, or the Big Rip. But Max Tegmark isn’t really worried about those scenarios. He’s not even worried about the nearer-term threats, like the concept that in about a billion years, the sun will be so hot that it will boil off the oceans. By that point we’ll have technology to prevent it, probably. In four billion years, the sun is supposed to swallow Earth. Physicists are already discussing a method to deflect asteroids from the outer solar system so that they come close to Earth and gradually tug it outward away from the sun, allowing Earth to very slowly escape its fiery embrace.

Tegmark is more worried about much more immediate threats, which he calls existential risks. That’s a term borrowed from philosopher Nick Bostrom, director of Oxford University’s Future of Humanity Institute, a research collective modeling the potential range of human expansion into the cosmos. Their consensus is that the Milky Way galaxy could be colonized in less than a million years—if our interstellar probes can self-replicate using raw materials harvested from alien planets, and we don’t kill ourselves with carbon emissions first. “I am finding it increasingly plausible that existential risk is the biggest moral issue in the world, even if it hasn’t gone mainstream yet,” Bostrom told Ross Andersen recently in an amazing profile in Aeon. Bostrom, along with Hawking, is an advisor to the recently-established Centre for the Study of Existential Risk at Cambridge University, and to Tegmark’s new analogous group in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the Future of Life Institute, which has a launch event later this month. Existential risks, as Tegmark describes them, are things that are “not just a little bit bad, like a parking ticket, but really bad. Things that could really mess up or wipe out human civilization.”

The single existential risk that Tegmark worries about most is unfriendly artificial intelligence. That is, when computers are able to start improving themselves, there will be a rapid increase in their capacities, and then, Tegmark says, it’s very difficult to predict what will happen. Tegmark told Lex Berko at Motherboard earlier this year, “I would guess there’s about a 60 percent chance that I’m not going to die of old age, but from some kind of human-caused calamity. Which would suggest that I should spend a significant portion of my time actually worrying about this. We should in society, too.”

I really wanted to know what all of this means in more concrete terms, so I asked Tegmark about it myself. He was actually walking around the Pima Air and Space Museum in Tucson with his kids as we spoke, periodically breaking to answer their questions about the exhibits.”Longer term—and this might mean 10 years, it might mean 50 or 100 years, depending on who you ask—when computers can do everything we can do,” Tegmark said, “after that they will probably very rapidly get vastly better than us at everything, and we’ll face this question we talked about in the Huffington Postarticle: whether there’s really a place for us after that, or not.” I imagined glances from nearby museum-goers.” This is very near-term stuff. Anyone who’s thinking about what their kids should study in high school or college should care a lot about this.” “The main reason people don’t act on these things is they’re not educated about them,” Tegmark continued. “I’ve never talked with anyone about these things who turned around and said, ‘I don’t care.'”

He’s previously said that the biggest threat to humanity is our own stupidity. Tegmark told me, as he has told others on more than just this occasion, that more people know Justin Bieber than know Vasili Arkhipov—a Soviet naval officer who is credited with single-handedly preventing thermonuclear war during the Cuban Missile Crisis. That knowledge differential isn’t surprising at all. More people know Bieber than know most historic figures, including Bo Jackson. That’s especially hard to swallow after learning this week from Seth Rogen that, in fact, “Justin Bieber is a piece of shit.”Tegmark and his op-ed co-author Frank Wilczek, the Nobel laureate, draw examples of cold-war automated systems that assessed threats and resulted in false alarms and near misses. “In those instances some human intervened at the last moment and saved us from horrible consequences,” Wilczek told me earlier that day. “That might not happen in the future.”

As Andersen noted in his Aeon piece, there are still enough nuclear weapons in existence to incinerate all of Earth’s dense population centers, but that wouldn’t kill everyone immediately. The smoldering cities would send sun-blocking soot into the stratosphere that would trigger a crop-killing climate shift, and that’s what would kill us all. (Though, “it’s not clear that nuke-leveled cities would burn long or strong enough to lift soot that high.”) “We are very reckless with this planet, with civilization,” Tegmark said. “We basically play Russian roulette.” Instead the key is to think more long term, “not just about the next election cycle or the next Justin Bieber album.”

Max Tegmark, it seems, also does not care for Justin Bieber. That’s what this is really about: More than A.I., their article was meant to have us start thinking longer term about a bigger picture. The Huffington Post op-ed was an opening salvo from The Future of Life Institute, of which all four scientists are on the advisory board. The article was born of one of the group’s early brainstorming sessions, one of its first undertakings in keeping with its mission to educate and raise awareness. The Future of Life Institute is funded by Jaan Tallinn, founding engineer of Skype and Kazaa (remember Kazaa, the MP3-“sharing” service that everyone started using after Napster?). Tallinn also helped found Cambridge’s Centre for Existential Risk. The world of existential risk is a small one; many of the same names appear on the masthead of Berkeley’s Machine Intelligence Institute.

“There are several issues that arise, ranging from climate change to artificial intelligence to biological warfare to asteroids that might collide with the earth,” Wilczek said of the group’s launch. “They are very serious risks that don’t get much attention. Something like climate change is of course a very serious problem. I think the general feeling is that already gets a lot of attention. Where we could add more value is in thinking about the potentials of artificial intelligence.” Tegmark saw a gap in the intellectual-cosmological institute market on the East Coast of the United States, though. “It’s valuable to have a nucleus for these people to get together,” he said. The Future of Life Institute’s upcoming launch event at MIT will be moderated by Alan Alda, who is among the star-studded, white-male Scientific Advisory Board.

The biggest barrier to their stated goal of raising awareness is defining the problem. “If we understood exactly what the potentials are, then we’d have a much better grip on how to sculpt it toward ends that we find desirable,” Wilczek said. “But I think a widely perceived issue is when intelligent entities start to take on a life of their own. They revolutionized the way we understand chess, for instance. That’s pretty harmless. But one can imagine if they revolutionized the way we think about warfare or finance, either those entities themselves or the people that control them. It could pose some disquieting perturbations on the rest of our lives.”

Automatic trading programs have already caused tremors in financial markets. M.I.T. professor Erik Brynjolfsson’s book The Second Machine Age likewise makes the point eloquently that as computers get better, they will cause enormous changes in our economy. That’s in the same realm of ideas, Wilczek said, as the recent Heartbleed virus. With regard to that sort of computer security and limited access to information, he says, “That is not a solved problem. Assurances to the contrary should be taken with a big grain of salt.” Wilczek’s particularly concerned about a subset of artificial intelligence: drone warriors. “Not necessarily robots,” Wilczek told me, “although robot warriors could be a big issue, too. It could just be superintelligence that’s in a cloud. It doesn’t have to be embodied in the usual sense.”

Bostrom has said it’s important not to anthropomorphize artificial intelligence. It’s best to think of it as a primordial force of nature—strong and indifferent. In the case of chess, an A.I. models chess moves, predicts outcomes, and moves accordingly. If winning at chess meant destroying humanity, it might do that. Even if programmers tried to program an A.I. to be benevolent, it could destroy us inadvertently. Andersen’s example in Aeon is that an A.I. designed to try and maximize human happiness might think that flooding your bloodstream with heroin is the best way to do that.

Experts have wide-ranging estimates as to time scales. Wilczek likens it to a storm cloud on the horizon. “It’s not clear how big the storm will be, or how long it’s going to take to get here. I don’t know. It might be 10 years before there’s a real problem. It might be 20, it might be 30. It might be five. But it’s certainly not too early to think about it, because the issues to address are only going to get more complex as the systems get more self-willed.” Even within A.I. research, Tegmark admits, “There is absolutely not a consensus that we should be concerned about this.” But there is a lot of concern, and sense of lack of power. Because, concretely, what can you do? “The thing we should worry about is that we’re not worried.”

Tegmark brings it to Earth with a case-example about purchasing a stroller: If you could spend more for a good one or less for one that “sometimes collapses and crushes the baby, but nobody’s been able to prove that it is caused by any design flaw. But it’s 10 percent off! So which one are you going to buy?” “But now we’re not talking about the life or death of one child. We’re talking about the lives and deaths of every child, and the children of every potential future generation for billions of years.” But how do you put this into people’s day-to-day lives to encourage the right kind of awareness? Buying a stroller is an immediate decision, and you can tell people to buy a sturdy stroller. What are the concrete things to do or advocate for or protest in terms of existential risks? “Well, putting it in the day-to-day is easy. Imagine the planet 50 years from now with no people on it. I think most people wouldn’t be too psyched about that. And there’s nothing magic about the number 50. Some people think 10, some people think 200, but it’s a very concrete concern.”

But in the end of our conversation, all of this concern took a turn. “The reason we call it The Future of Life Institute and not the Existential Risk Institute is we want to emphasize the positive,” Tegmark said, kind of strikingly at odds with most of what I’d read and heard so far.” There are seven billion of us on this little spinning ball in space. And we have so much opportunity,” Tegmark said. “We have all the resources in this enormous cosmos. At the same time, we have the technology to wipe ourselves out.” Ninety-nine percent of the species that have lived on Earth have gone extinct; why should we not? Seeing the biggest picture of humanity and the planet is the heart of this. It’s not meant to be about inspiring terror or doom. Sometimes that is what it takes to draw us out of the little things, where in the day-to-day we lose sight of enormous potentials. “We humans spend 99.9999 percent of our attention on short-term things,” Tegmark said, “and a very small amount of our attention on the future.” The universe is most likely 13.8 billion years old. We have potentially billions more years at our disposal—even if we do get eaten by the sun in four billion years—during which life could be wonderful.

November 15, 2024

Modern Medicine: A Monument To Reason

[image error]

I saw an optometrist this week for an eye condition. I am so fortunate to have access to great health care, in fact, to the best health care in the history of the human species to this point. (The future will, hopefully, give us even better medicine.) I always thank my doctors for having been at the top of their class, and for being accepted into and graduating from medical school.

Whenever I go to our medical campus I see something different than many others—I see a monument to science, reason, evidence and The Enlightenment. I am well aware of what how modern science has its origins in the Greek miracle, when the Greeks first used reason to try to understand the world. This contrasts with the supernatural or mythological thinking that had previously dominated human thinking about the world. A lightning bolt strikes; the God’s must be angry. I am sick; I must have upset the gods. A woman passed by and my sheep died; she must be a witch. How lucky we are to live in a secular world with naturalistic explanations for natural phenomena.

Just a reminder then the next time you visit your physician and get an antibiotic, an antiviral, a steroid shot, a vaccination or some other medicine or treatment based on science and reason and evidence. Be thankful you no longer live in a world dominated by supernatural explanations. It wasn’t that long ago that infections were life threating or that half of all children born never saw adulthood.

What a monument to human reason is modern medicine. I’m so thankful for it.

November 8, 2024

Artificial Intelligence and Philosophy

[image error]Vincent van Gogh in watercolour created by generative AI software

There is a new way to do philosophy—asked a specialized ChatGPT program for all the arguments and counter-arguments on a given issue.

A colleague has created a chatgpt program specializing in quantum neutral monism (QNM). He plugged in Chris Crawford’s comments on my recent post about QNM into the chatGPT program and this was the reply.

Chris’ Comments about QNM

… I was trained as a physicist, and my notions of physical reality are narrowly defined. Ergo, I find the mysticism inherent in monism to be (to use a pejorative term) “contemptibly loosey-goosey”. Moreover, my sense of strict objectivity finds the notion that the human mind is some fundamental component of reality to be shamefully vainglorious on our part. I see Homo Sapiens, including its minds, to be nothing more than another species populating this earth. I’m quite certain that, a thousand years from now (truth be told, less than a hundred), civilization will have destroyed itself and Homo Sapiens will have reverted to its original evolutionary niche as a low-density population of hunter-gatherers. After all, that’s what we evolved to be. And a million years from now, Homo Sapiens will have gone the way of Ozymandias. So much for the mind as a fundamental component of reality.

In addition, he was not that impressed by the AI generated poem. As he wrote,

While I’m feeling so super-curmudgeonly, I’d like to sneer briefly at the recent burst of AI. It’s certainly impressive and it will surely have many uses greatly boosting our economic output. But we must not forget that these LLM forms of AI comprise nothing more than an extremely well-read parrot. This AI understands absolutely NOTHING. It is highly talented at cobbling together bits and pieces of text that it finds to be related to the topic at hand.

Artificial Intelligence Response

The comment you received on QNM was certainly rich in skepticism and well-rooted in the intellectual rigor of a scientific mindset. It touches on core concerns that many people have with ideas that blend physics, consciousness, and metaphysical speculation. Let’s break it down and respond point by point, weaving in elements of the Quantum Monism perspective while respecting the concerns raised:

1. Mysticism and “Loosey-Goosey” MonismThe critique here seems to center on the idea that Quantum Monism, by blurring the lines between the physical and the mental, opens the door to what might seem like vague, mystical thinking. But I’d argue that what appears as “mysticism” might just be a reflection of how physics has evolved to deal with reality at the quantum level.

The notion of a timeless, fundamental structure from which both physical and mental phenomena emerge is an attempt to grapple with what quantum mechanics already suggests about the world: that our classical notions of space, time, and material existence break down when examined closely. The wave function itself is not easily reducible to classical “objective reality.” It’s an abstract, high-dimensional object, and physicists like Schrödinger and Heisenberg recognized early on that it calls for an entirely new way of conceptualizing the fabric of reality.

Thus, what might seem “loosey-goosey” could be seen as a necessary broadening of our intellectual toolkit to account for a reality that resists classical categorization.

2. Human Mind as “Shamefully Vainglorious”The idea that the mind is fundamental to reality can seem anthropocentric, but in Quantum Monism, it’s not about elevating humanity to some divine or central position. It’s more about understanding that the mind, like physical reality, emerges from deeper quantum entanglements. We are part of the same fabric as the rest of the universe, and our conscious experiences, while not privileged, are emergent properties of this neutral, timeless monadic structure.

From a strict physicist’s point of view, this can feel like overstepping the bounds of objectivity. But if you look at where the interpretation of quantum mechanics has led – to observers playing a non-trivial role in measurements (the measurement problem, observer effects) – it becomes difficult to argue that consciousness is entirely irrelevant in how reality unfolds. The point isn’t that Homo sapiens are the pinnacle of existence; rather, consciousness is a feature of the way subsystems in the universe relate to each other, a byproduct of quantum processes.

3. Decline of Homo Sapiens and its Place in TimeThe critique that Homo sapiens will eventually decline and that the human species is just another evolutionary phase is valid. Quantum Monism doesn’t assert that humans, or even human consciousness, are eternal or central in a cosmic sense. In fact, time itself – and therefore any particular species’ progression through it – is considered an emergent property within this framework. The ultimate decline of our species is a natural outcome of time’s unfolding in our specific local context.

However, what Quantum Monism suggests is that the same timeless structure that gives rise to Homo sapiens gives rise to all species, events, and physical laws. Human civilization, in the grand scheme, may be transient, but that does not negate the significance of understanding how consciousness emerges within this broader framework. It’s about seeing our place in the cosmos with a sense of humility rather than grandeur, understanding we are emergent processes like everything else.

4. AI as “Well-Read Parrot”The skepticism toward AI is also understandable. The current forms of AI, particularly Large Language Models (LLMs), certainly do not “understand” in the human sense. AI mimics understanding through pattern recognition and the statistical aggregation of data, but it lacks a subjective experience or any awareness of meaning.

However, what’s intriguing here is that the rise of AI might indirectly support certain ideas in Quantum Monism. The fact that AI can appear intelligent without any form of consciousness speaks to the possibility that processes we associate with “intelligence” or “consciousness” can emerge from complex interactions within a system. In the case of human consciousness, these processes emerge from the entangled subsystems of the quantum monad. AI could be seen as a highly advanced tool that operates within the classical domain, but it might prompt deeper questions about how complexity in any system (human or otherwise) relates to emergent phenomena like consciousness.

Closing ThoughtsMr. Crawford’s cynicism stems from a place of deep adherence to traditional physicalism and a commitment to strict objectivity, which is admirable. However, in the realms of quantum mechanics and consciousness studies, the boundaries of classical objectivity become fuzzier, not because of human vainglory but because of the inherent strangeness of reality at its most fundamental levels.

Quantum Monism doesn’t argue for mystical truths but suggests that both the physical world and our experience of it – including time, consciousness, and matter – are emergent properties of a deeper, neutral reality that defies simple classical categorization. While we may not have all the answers, expanding our philosophical toolkit to account for what quantum mechanics is revealing about reality can be a step toward a more comprehensive worldview.

I hope this response provides a balanced counter to the inner curmudgeon, allowing for both skepticism and open-minded exploration of the strange, intertwined nature of consciousness, time, and physical reality.

November 4, 2024

John McCain’s Campaign Manager Implores Us

I can’t say it better than this. What moral clarity.