John G. Messerly's Blog, page 52

February 18, 2020

How To Survive Trump

As usual Doug Mudar wrote a profound post, “Let’s Talk Each Other Down,” at his website The Weekly Sift. Mudar begins like this:

Looking around this week — in the media, among my friends, inside my own head — I observed that a lot of people are freaking out. Because Trump was acquitted, because he has started his revenge tour, because Republicans know he abused his power and don’t care, because the Democrats are doing it all wrong, because a virus is spreading out of control, because the State of the Union was full of lies, because both the National Prayer Breakfast and the Medal of Freedom have been desecrated, because a US senator willfully and illegally endangered the life of a whistleblower, because it’s been 65 degrees in Antarctica, because the Attorney General has given Trump carte blanche to violate campaign laws, because a billion-dollar disinformation project has begun, and because, because, because.

Now Mudar admits that he doesn’t know it’s all going to be ok. Not only because the signs are ominous, but because the future is uncertain. Moreover, you

might be in this state of uncertainty for the rest of your life. Maybe we’re doomed, but maybe we’re not. Nobody really knows. Democracy in America might soon be over, or it might get a reprieve. Truth might finally drown in a sea of disinformation, or maybe it will figure out how to swim in that sea. People are endlessly surprising. Just when you think they’re hopeless, they do something hopeful. And vice versa.

His main point then is that we don’t know that we’re all doomed either. That may not be much to hang your hat on, but’s it is something. After all, even if we don’t know things will be ok, we can still try to make things better. And we might succeed. But if

you’re waiting for a guarantee, for a political almanac that will tell you exactly when the sun will rise and the tide will turn, you’ll keep waiting and you’ll do nothing. Don’t go that way. Be hopeful. Throw your effort out there and see what happens. Because you never know.

That’s about the best we can do. Hope and act for the best, accepting that the outcome is uncertain. Thank you Dr. Mudar.

February 13, 2020

Francis Heylighen: Meaning and Worldviews

© Francis Paul Heylighen – (Reprinted with Permission)

Francis Heylighen is a Belgian cyberneticist investigating the emergence and evolution of intelligent organization. He presently works as a research professor at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel where he directs the transdisciplinary research group on “Evolution, Complexity and Cognition” and the Global Brain Institute. He is best known for his work on the Principia Cybernetica Project, his model of the Internet as a global brain, and his contributions to the theories of memetics and self-organization.

Below is the final section of his notes for the course he teaches called, “Mind, Brain and Body: a systemic perspective on the human condition.” It is a most worthwhile read.

Part 1 – The need for meaning

The problem of self-uncertainty is not solved just by developing an accurate self-concept. You not only need to know who you are, but how you fit in with the larger social and natural world, what you should do, and why. Happiness research, as well as philosophical reflection, has made it clear that people need a sense of purpose or meaning that gives direction to their life.

[image error]

The psychiatrist Viktor Frankl wrote an influential book, Man’s Search for Meaning[image error] in which he describes his experiences as a prisoner in a Nazi extermination camp. He observed that in these extremely harsh circumstances, in which people were robbed of any remains of their social identity, many just gave up and did not care anymore to survive. For them, without all the social values, norms, and things like status and possessions that gave them self-esteem, life seemed meaningless, and no longer worth clinging to. Those people were the first to die.

However, some people, including Frankl himself, managed to find meaning even in a

situation where they apparently had no control whatsoever over their fate. For example,

they might reflect about what they had achieved in their life before they were imprisoned,

or how they might use their painful experiences if ever they would be released (like writing a book about them, as Frankl did). Those were the people most likely to survive and to remain psychologically healthy. That inspired Frankl after the war to develop his “logotherapy” approach to help people with psychological problems find meaning in their

life.

Part 2 – What is meaning?

But what precisely is this meaning that people are looking for? What is it that makes

something meaningful or significant? How do we make sense of things?

The problem can be illustrated with a situation that is easy to imagine. Suppose that you walk into your office and discover a large, weirdly shaped contraption sitting on your desk. You do not know what it is, how it got there, what its function is, or what you are supposed to do with it. It simply does not fit into your understanding of the kind of situation that you expect to encounter in an office. Your natural reaction will be to ask: “What is the meaning of this?”

The question is simple, spontaneous and intuitive. However, it is not obvious to specify

what precisely would constitute an adequate answer. Describing the contraption is easy

enough: it has a specific shape, colors, parts, material… These properties can be established more or less objectively, by careful observation. But the meaning of the contraption is not in these visible components: it needs to emerge from the mind of the person that is confronted with it. Yet, meaning is not just a subjective impression: most of the time people agree about what things mean. While difficult to define or delimit, meaning is something we can recognize when we find it, and communicate it to others.

For example, suppose your colleague tells you that the contraption is an artwork that the

director received as a present. Knowing your interest in art, the director wanted your

opinion whether this piece would be suitable to exhibit in the entrance hall of the building.

That is how it ended up on your desk. Suddenly, the whole situation makes sense. While

you still do not know who made it, or what the creator’s intentions were, the contraption

has acquired a basic meaning. You know how to interpret it and how to react to it.

Thus, people are engaged in an on-going process of sense-making, of constructing ever

more refined and elaborate meanings for the phenomena and situations that they encounter. This process takes place simultaneously at different levels, from simple sensations (what was that sound I heard?), words (what did you say?), expressions (what do you mean by that?), more complex situations (what is going on here?), to a broad, global appraisal (what is the meaning of (my) life?). This process is the essence of cognition, mind and life: in order to survive, we need to make sense of the phenomena that confront us, so that we know how to deal with them. In order to advance and develop, we need to create new meanings, make new connections, see known things in a new light so that we discover novel ways to deal with them.

Part 3 – Existential meaning

More generally, we try to understand how our own life fits into the larger whole formed

by our natural and social environment. We also look for a direction in life, a system of

goals and values that tells us what to do, what to strive for, what to avoid. This leads many

people to ask the existential question: why do we exist? What is the meaning of life?

[image error][image error]

The existentialist philosophers, such as Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus, concluded that life is intrinsically absurd or meaningless. We just exist. There is no a priori reason or essence that explains who we are or why we are here. This rather depressing answer was inspired in part by the absurdities of the two world wars, including the extermination

camps that had marked Viktor Frankl. Another reason was the insight that philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche had formulated much earlier as “God is dead”. By this he meant that modern science has created a picture of the universe in which there is no longer any room for a God that tells us what we should do, and controls whether we obey His commandments.

In the older, religious worldview, purpose and meaning are imposed from the outside. We are supposed to follow God’s plan without doubting or questioning. If we do not, we will get our deserved punishment and suffer in Hell. If we do, we will be rewarded by an eternal life in Heaven. The world around us was created by God, and thus reflects His designs. This establishes an explicit system of values, norms, and explanations, or what we will further call a worldview (Vidal, 2012).

The worldview of science, on the other hand, may provide explanations, but it does not

provide norms or values. These scientific explanations seem to imply that we do not really

have a choice in how to behave, since events are either fully determined by the laws of

nature, or merely random and accidental. Therefore, to many people it seems as if science

implies that there is no meaning in life.

The solution proposed by Camus is that even though life is absurd, you need to rebel

against this absurdity and choose a purpose for yourself, leading your life as if there were

no absurdity (Camus, 2018). While Frankl formulates his philosophy in a more positive

way, his message is essentially the same: meaning is something we create for ourselves,

not something we can find in some big book of scriptures. Maslow and other humanists

formulate it even more positively: our nature as human beings is to maximally grow and

develop ourselves. We are free in choosing how to do this, but the drive to grow and to

seek and find meaning is already built into our mind and body. If we want to be happy, we

should follow that drive.

My own position (which I develop in more detail in my course on “Complexity and Evolution” (Heylighen, 2014b)) goes even further: this drive for growth and development is

not just part of human nature, but of life, and even the universe, in general. Contemporary

science shows that evolution has a preferred direction towards greater synergy, complexity

and intelligence. Therefore, life is intrinsically meaningful. Nevertheless, we are still free

in choosing how best to develop, and we must make sense of each new challenge we are

confronted with. Let us then try to understand more precisely what this sense-making

process consists of.

Part 4 – Components of meaning

To understand more concretely what meaning is, we must go back to our initial understanding of people as agents that interact with their environment. As we saw, agents are confronted with external phenomena that they perceive (challenges). They must make

sense of these phenomena in order to decide about the right action to take. That action

affects the phenomenon, triggering a new perception that leads possibly to a new action, in an on-going feedback loop between agent (subject) and phenomenon (object). This already defines three fundamental aspects of sense-making or meaning:

1) perception or knowledge acquisition: the agent should be able to gather information

and thus find out more about the phenomenon.

2) values or goals: the agent should be able to compare the situation as it understands it

with its preferences or desires, so as to decide whether the situation is OK as it is, or

should somehow be changed to make it better. That requires an evaluation of the phenomenon in terms of how positive (good) or negative (bad) it is. For example, seeing

an apple is good, but having the apple in your mouth to eat it is even better. Feeling

your hand being burned by a flame is bad, and therefore you should do something to

get your hand away from the heat.

3) action: once the agent has decided in what way the situation requires improvement, it

needs to find out which actions it could perform on the object to bring about that improvement. In the case of the apple, a possible action is to climb a ladder so that you

can grasp the apple and bring it to your mouth.

These three components are sufficient for a simple agent, such as bacterium, that functions according to simple condition-action rules. The bacterium should be able to sense its situation (1), evaluate to what degree it is good (e.g. being in the presence of food) or bad (e.g. being in the presence of poison) (2), and perform some action to make it better (e.g. move away from the poison and towards the food) (3).

More intelligent, “mindful” agents, such as human individuals, moreover need a deeper, more objective understanding of the situation or phenomenon independent of themselves. That allows them to better predict what will happen under different conditions or actions. That implies three more fundamental aspects of meaning:

4) properties: what kind of thing is it? What does it consist of? How would it react to different kinds of actions?

5) consequences or future: what is likely to follow? What will it lead to? To answer these questions, we normally need to first ask the following question:

6) origin or cause: where does that phenomenon come from? Why is it there? What caused it to happen?

Let us illustrate this 6-component scheme with an example we discussed in the context of

the brain. Suppose you see some movement underneath a bush in your garden, but it is not clear what is going on there. Your natural reaction is to try and make sense of the situation, so as to know what you should do.

First, you need to acquire more information (1): you will look more carefully and possibly push away some branches to get a better view. That may give you a better understanding of what it is (4) there under the bushes: a cat. Your next questions are likely to be: where did that cat come from (6), and what is it going to do (5)? If it is the cat of the neighbors, it is likely to just return to the neighbors’ garden, and you don’t need to do anything. But perhaps the cat looks miserable and frightened, so it may be lost. Your sense of values (2) tells you that that is not a good situation, so you need to do something about it. Therefore, you consider which actions would be appropriate in this situation (3), such as feeding the cat some milk, calling the animal rescue service, or asking around to check whether anybody has lost a cat.

Part 5 – Worldviews

The sense-making process as we just described it is very general. It is something we automatically apply to any kind of issue we are confronted with. This goes from immediate, local ones, such as a cat under the bush, or a contraption on the desk, to more general ones with consequences that extend over a longer period, such as the new requirements at work, or the political situation, to more global, long term ones, such as the impact of climate change. In each case, we interpret the situation in terms of the six components of meaning. At the largest scale, the issue is existential, about the meaning of life in general.

More concretely, the existential issue is to understand the role of humankind (the agent) with respect to the world (the phenomenon). “World” here means the totality, everything that exists around us, including the physical universe, the Earth, life, mind, society and

culture. A worldview can be defined as a global meaning-producing system. That means a general framework that helps us to answer the six sense-making questions. Thus, it would give direction and meaning to life.

This conception of a worldview was developed by the Belgian philosopher Leo Apostel (photo) and his colleagues in the “Worldviews” group (Aerts et al., 2002). Let us reformulate the six aspects of meaning as the six components of a worldview according to Apostel (using a different order from the sense-making scheme):

Ontology (model of the world):

This answers the question: “What is the world?” (4) It should provide a description of the

fundamental constituents and properties of the universe, such as matter and energy. In

philosophy, this corresponds to the domain of “ontology”, or the theory of what is or what

exists. It should allow us to understand how the world functions and how it is structured.

Metaphysics (explanation):

This answers the questions: “Why is the world the way it is? Where does it all come from?

Where do we come from?” (6). This is perhaps the most important part of a worldview. If

we can explain how and why a particular phenomenon (say life or mind) has arisen, we

will be able to better understand how that phenomenon functions and what it will lead to.

Futurology (model of the future):

This answers the question “Where are we going to?” (5). It should give us a list of possibilities, of more or less probable future developments.

Axiology or ethics (theory of values):

This answers such questions as: “What is good and what is evil? What should we strive for

and what should we avoid?” (2) This component includes morality or ethics, the system of

norms that tells us how we should or should not behave. It also gives us a sense of purpose, a direction or set of goals to guide our actions.

Praxeology (theory of action):

This answers the question “How can we act effectively?” (3) It is intended to help us to

solve practical problems and to implement plans of action.

Epistemology (theory of knowledge):

This answers the question “How can we acquire reliable knowledge?” (1). It should allow

us to distinguish better explanations or theories from worse ones. It should answer the

traditional philosophical question “What is true and what is false?” Actually, Apostel also listed a seventh component: integration of the different fragments of knowledge. This does not correspond to a specific part of the sense-making scheme, but rather reminds us that all elements are to be connected into a coherent view of the whole.

Part 6 – Assimilation and accommodation

The function of a worldview is to help us make sense of the important events in our life.

Such events may include a new job or project, the death of a loved one, a new relationship,

or a serious illness. When we manage to explain and evaluate such an event on the basis of

our worldview or some other meaning-producing scheme, then the event has been assimilated into the scheme: it is made to fit into our understanding of how the world functions.

However, if that fails, then the worldview itself may need to change in order to understand

what has happened. In such a case, sense-making requires accommodation of the worldview to the event, rather than assimilation of the event into the worldview. Such a drastic event that triggers a change of the meaning-producing system has been called a “cosmology episode” by the sociologist Karl Weick, since it implies a new perspective on the world (cosmos) (Weick, 1995).

Meaning-making is necessary when some event happens of which the initial interpretation

is discrepant with the global beliefs and values, so that it does not fit within the standard

scheme. For example, a hard-working employee who is proud of his achievements may be

suddenly dismissed from his company. Assuming this person believed that productive

effort leads to advancement, and that career advancement is the major goal of his life, the

dismissal will not only not make sense to him, it may put into doubt his very conception of

his life in relation to the world as he knows it. The natural reaction is to try to reduce the

discrepancy between the initial interpretation of the event (“I was dismissed in spite of my

hard work”) and the global meaning system (“I should work hard to achieve a well-deserved advancement”).

This can happen by changing the initial interpretation, thus making sense of the situation

in a different way (e.g. “the company is financially in dire straits, so they had to let some

of their best people go”). In this case, the dismissal is attributed to a cause that does not

clash with the “working hard” value. The apparently discrepant situation has now been

assimilated into the worldview (“as long as finances allow, hardworking people are rewarded with advancement, so I should not let this setback stop me from continuing to

work hard”). Assimilation means that meaning has been found without the worldview

needing to change.

Accommodation is the more drastic process in which making sense of the situation requires a reorganization of the worldview itself (a “cosmology episode”). For example, the

dismissed employee may suspect that he was cheated by a competitor, who blackened his

name in order to get him dismissed and take his job, and conclude that “to reach my goals

it is better to cheat than to work hard”. Here a new meaning is created not just for the local

event, but also for the person’s global appraisal of life.

For another example, imagine that a person has a religious worldview according to which

good people are rewarded by God with a long and happy life, while bad people are punished. When that person’s beloved younger sister is killed on the road by a drunk driver, while the driver escapes punishment, this assumption comes under severe stress. One option is to still assimilate the event into the worldview, e.g. by assuming that the sister will anyway live happily in Heaven, while the driver will go to Hell, and that God intended this episode merely to test the family’s faith in Him. Another option is to accommodate the worldview, and conclude: “the benevolent God I believed in would never allow such an event to happen, therefore I must have been mistaken and God does not exist”.

Part 7 – The need for a new worldview

We live in a time that is characterized by very rapid, confusing, and difficult to understand

changes. We suffer from information overload and constant interruptions, caused by the

ubiquitous Internet, smartphones, and a globalized society, where faraway events can

immediately affect what happens here and now. The situation can be described by the

VUCA acronym. That means that it is:

Volatile: most things change rapidly, while very few things are permanent

Uncertain: we rarely can predict what will happen next

Complex: all these changes depend on each other in a way very difficult to grasp

Ambiguous: we do not really know what these changes are or what they mean

In sum, it is difficult to make sense of what is presently happening in the world. The resulting lack of meaning produces stress, alienation (feeling as if you don’t belong), and a

general sense of insecurity and self-uncertainty. As we saw, this is a basis for unhappiness.

It also tends to trigger a variety of psychological problems, such as depression, anxiety,

violence or even suicide.

We further saw that people suffering from self-uncertainty tend to compensate for this by

adopting social norms that are clear but simplistic and rigid. Thus, the situation makes

people attracted to worldviews that promise the opposite of the VUCA properties, by

proposing explanations, norms and values that are:

Eternal, rather than volatile,

Absolute, rather than uncertain,

Simple, rather than complex, and

Strictly defined, rather than ambiguous.

Such worldviews can be found e.g. in fundamentalist religions, nationalistic ideologies

and totalitarian systems. However, such worldviews merely deny the obvious VUCA

nature of our society, rather than addressing its challenges. That typically makes the problems worse rather than better—just like denying global warming would stop us from

developing policies that can mitigate its effects.

While such a rigid worldview can make people temporarily feel better, it does not propose

a strategy to reach a true understanding of unusual phenomena, because it will always

have an ad hoc explanation that can apply to anything. For example, in a religious worldview, like in the example of the sister killed by a drunk driver, any unexpected event can be explained by God’s inscrutable intentions that we just have to accept. Nationalist political worldviews, on the other hand, tend to attribute all problems or failures to some conspiracy by enemy forces. If no evidence of the conspiracy can be found, this merely

confirms that the conspirators are very powerful in hiding the evidence.

An effective worldview must provide a realistic description of the world, and a strategy to

deal with it that actually works. That means that we need a worldview that accepts change,

uncertainty and complexity, but that focuses on the positive aspects of how we can use

that complexity and change to work for us and make the world better. That is why I advocate an evolutionary-systemic worldview. Here people are seen as complex systems interconnected and embedded within other systems, including society and the ecosystem.

These systems through their interactions mutually adapt, discover synergies, and thus

develop, self-organize and evolve.

Part 8 – Creation of new meanings

No worldview can ever be finished or complete: we will never be fully certain, and there

will always be new phenomena, changes and mysteries to explore and make sense of.

Therefore, the evolutionary-systemic worldview is open-ended: permanently ready to

accommodate new insights. Thus, we need to continue searching for meaning. The traditional way is through symbolic reasoning: using language and logic to develop new explanations that relate known concepts (symbols) in a novel way, while using intuition to

select the most plausible and meaningful ones. But this is not sufficient (Heylighen, 2019).

The ambiguities of language and intuition can be overcome to some degree by the methods of science. By formalization (expressing symbols in an explicit, context-independent manner, like in mathematics), we can make our descriptions more precise and less subjective. By operationalization (grounding symbols in physical operations, such as experiments or measurements, that specify how the symbol is related to an external phenomenon), we connect these abstract descriptions to the real world. By testing our theories in that real world, we make sure their predictions are reliable.

However, not all meaning can be expressed in a strict, formal and operational manner.

Philosophy helps us to address questions as yet left unanswered by science, in particular

by searching for the deeper concepts, assumptions or foundations that support our theories, and by questioning conventional wisdom or seemingly obvious parts of our worldview. Philosophy also should help us to integrate the often-disconnected insights from science into a worldview that helps us answer all the “Big Questions” (Vidal, 2012).

Art can support us in this meaning-creating enterprise through its power to evoke feelings,

experiences and intuitive insights that cannot be expressed in words or conventional symbols. Thus, it stimulates our senses and imagination, making use of our “situated and

embodied” cognition to better grasp complex phenomena, such as shapes, movements or

sound sequences (Johnson, 2008).

Meditation, mindfulness and other “spiritual” techniques further open up our consciousness to the more subtle sensations and associations that tend to be ignored by rational, symbolic thinking (Heylighen, 2019). This makes us ready to transcend our individual, self-centered perspective, and to feel more connected to the larger whole—humanity, nature and the cosmos.

Thus, we feel awe in the face of the unimaginable complexity of the universe, and fascination for the mystery of everything that is still unexplained. But this mystery is not locked away as something that we could and should never try to comprehend, the way it is often portrayed in religions. On the contrary, it should stimulate our imagination and curiosity, and inspire us to question conventional assumptions and discover new meanings.

Still, the complexity of the universe is not just something negative, which casts doubt on

everything we know. It should also be seen as a source of growth and self-organization.

This may give us faith in the power of evolution to always find creative solutions to whatever challenges may appear. For this, we can find inspiration in what is nowadays called “Big History”, i.e. the story of the universe’s evolution from the Big Bang to contemporary civilization, and beyond.

As an overall conclusion, the meaning of human life is to live, develop and grow, while

seeking more harmony and synergy with the surrounding social, ecological and cosmological systems. For an individual human that means self-actualization, in the sense of maximally developing your talents, and self-transcendence, in the sense of applying these talents to help develop something bigger than your self.

Bibliography

Aerts, D., Apostel, L., De Moor, B., Hellemans, S., Maex, E., Van Belle, H., & Van der

Veken, J. (2002). Worldviews: From fragmentation to integration. Retrieved from

http://www.vub.ac.be/CLEA/pub/books/w...

Camus, A. (2018). The Myth of Sisyphus (Translation edition). Vintage.

Heylighen, F. (2019). Transcending the Rational Symbol System: How information technology integrates science, art, philosophy and spirituality into a global brain. In A. Lock, N. Gontier, & C. Sinha (Eds.), Handbook of Human Symbolic Evolution. Retrieved from http://pcp.vub.ac.be/Papers/Transcend...

Johnson, M. (2008). The meaning of the body: Aesthetics of human understanding. University of Chicago Press

Vidal, C. (2012). Metaphilosophical Criteria for Worldview Comparison. Metaphilosophy,

43(3), 306–347. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9973.2...

Weick, K. E. (1995). Sensemaking in organizations (Vol. 3). Sage

February 11, 2020

International Conference on Philosophy and Meaning in Life

The 3rd International Conference on Philosophy and Meaning in Life will be held June 17-19, 2020 at the University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK. The keynote speakers will be John Cottingham (Professor Emeritus of Philosophy, University of Reading) and Lisa Bortolotti (Professor of Philosophy, University of Birmingham).

The aim of the conference is to address fundamental questions about the meaning of and in life from a wide range of philosophical perspectives. Potential topics include: philosophical approaches to meaning in/of life; the relationship between death and meaning; anti-natalism and nihilism; procreation; spiritual, religious and psychological implications of meaning; metaphysical and epistemological issues concerning meaning; meaning in applied ethics, bioethics and environmental ethics; meaning in religious and philosophical traditions around the world; implications of meaning for health.

The conference works in close connection with the Journal of Philosophy of Life. The aim of this journal is to promote international dialogue on the philosophy of life. It features original, full-length papers as well as research reports and other relevant materials. Every paper in the journal is published in PDF format and is freely downloadable.

The journal defines philosophy of life as an academic research field that encompasses the following activities:

1) cross-cultural, comparative, or historical research on philosophies of life, death, and nature.

2) philosophical and ethical analysis of contemporary issues concerning human and non-human life in the age of modern technology.

3) philosophical analysis of the concepts surrounding life, death, and nature.

__________________________________________________________________________

I will try to read some of the essays in the journal and summarize them on the blog soon.

February 7, 2020

Review of Jason Brennan’s “Against Democracy”

[image error][image error]

(This essay originally appeared at 3 Quarks Daily. Reprinted with permission.)

“Political Hooligans” by Scott F. Aikin and Robert B. Talisse

Although the word “democracy” is commonly used to denote all that is good in politics, democracy is a dubious proposal. It is the thesis that you may be required to live according to rules that you reject, simply because those rules are favored by others. What’s more, democracy is the proposal that you may be rightfully forced to live according to rules that are supported only by others who are ignorant, misinformed, deluded, corrupt, irrational, or worse. Further still, under democracy, you may be rightfully forced to live according to the rules favored by a majority of your fellow citizens even though you are able to demonstrate their ignorance and irrationality, and despite the fact that you can debunk the rationales they offer in support the rules that you oppose. Democracy apportions political power to citizens as such rather than according to their ability to wield it responsibly.

The aspiration of democracy is that with its freedoms, we allow reasons to be exchanged so that the best will come to be recognized. Note that this is true of democracy at its best. And we know that real-world democracy is far from the ideal. We are in fact forced to live according to rules that are favored by ignorant, misinformed, and irrational citizens; and many of the rules we are forced to live by are defensible only by way of the flawed rationales embraced by the ignorant. In real-world democracy, we are indeed at the mercy of our irrational and ignorant fellow citizens. Knowing this, politicians and officials cater to majority irrationality, and, once in power, they govern for the sake of gaining reelection.

It’s difficult to see what could justify democracy. Maybe this is as it should be? Even under ideal conditions, political orders are always coercive, and so the task of justifying any mode of politics should be onerous. And the difficulty of justifying democracy should increase under non-ideal conditions such as those we currently face. Part of the task of democracy, even in its most ideal versions, is to critically assess the prevailing democratic order. And one way to assess a democracy is to envision alternative arrangements that might be superior.

In a recent book, provocatively titled Against Democracy, Jason Brennan takes up the chore of assessing existing democracy. His central contention is appropriately modest. He claims that if there is a workable nondemocratic political arrangement that can reasonably be expected to more reliably produce morally better policy decisions than existing democratic arrangements, we ought to try that alternative arrangement. Ultimately, he identifies a range of alternatives that he alleges will outperform democracy, all of which instantiate a political form he calls (borrowing a term coined by David Estlund) epistocracy, the rule of the knowers.

Hence Brennan’s argument is comparative; he aims to identify epistocratic alternatives that are better than democracy. Accordingly, he proceeds from a fairly dismal depiction of the state of the democratic citizenry. Brennan proposes a taxonomy of democratic character types: hobbits, hooligans, and Vulcans. Hobbits are uninterested in politics and so lack political information, frequently are devoid of stable political opinions, and tend to not vote. Hooligans, by contrast, consume political information and have strong and stable political views. However, they reason and gather political information in biased ways; they tend to be politically active, but they also tend to regard their political opposition as evil, ignorant, deluded, or worse. Vulcans are properly-behaved political epistemologists; they have well-grounded views, know the relevant social science and philosophy, and are able to disagree respectfully with others. However, as the requisite knowledge and dispositions are difficult to acquire, Vulcans are scarce.

According to Brennan, the trouble with democracy is that it is teeming with hooligans, “the rabid sports fans of politics.” More than this, democracy tends to encourage political hooliganism. And as the citizenry is hooliganized, it is mobilized in the direction of policies that are increasingly unjust and harmful; hence, according to Brennan, democracy turns us all — including Vulcans — into civic enemies. Hence democracy rots from the inside.

Brennan’s account of the corruption of democracy is undeniably resonant. Still, his depiction of the hooligan raises a difficulty. Unlike the images of the hobbit and the Vulcan, the portrayal of the hooligan is strictly second- or third-personal. That is, only the hobbits and Vulcans can embrace Brennan’s rendering of their political character. That is, hobbits are capable of assessing themselves as hobbits, and the same goes for Vulcans. Not so with the hooligans.

The trouble with the hooligans is not simply that they form political opinions in epistemically irresponsibly ways and then behave badly in the political arena; it’s also that they take themselves to be Vulcans. From the inside the hooligan takes himself to be a paragon of wisdom. His biases look to him like principles, his vices look like virtues, and his tribal allegiance to his political team looks to him perfectly rational. Political hooligans cannot understand themselves as such. To sincerely assess one’s reasoning as plagued by bias is to lose confidence in one’s reasoning. To assess one’s belief as the product of systematic epistemic dysfunction is to see the belief itself as corrupt. Delusion and self-deception are ineradicable parts of the political hooligan’s profile.

One might wonder, then, who Brennan’s audience is. The hobbits don’t read books about politics and don’t care about arguments in political philosophy. The politically-engaged all take themselves to be Vulcans (or at least not hooligans), and most of them are frustrated by the current state of democracy. But only a few of them (i.e., the true Vulcans) are actually moveable by reason and argument. Hence the hooligans will welcome Brennan’s call for epistocratic alternatives, but this is because they take themselves (and their fellow tribesmen) as especially strong candidates for leadership roles in whatever epistocratic order might take shape. Being hooligans, they believe themselves to be Vulcans, and they also are not susceptible to rational demonstration of their hooligan nature. Therefore any attempt to design an epistocracy that does not empower them (or members of their political tribe) will be regarded by them as yet another corrupt power-grab by their incompetent and sinister political enemies.

Accordingly, given Brennan’s diagnosis of the trouble with democracy, the prospect of designing and implementing an episocratic alternative, even as an experiment to be tried, seems doomed. Given what hooligans are, any epistemologically responsible selection of an epistocratic body will be perceived by the majority of politically-active citizens (who are hooligans) as either rigged to favor their enemies, or designed to oppress their enemies. The hooligans of the former stripe will oppose the epistocratic innovation, and, as they’re hooligans, their opposition will take unwelcome forms. The hooligans of the latter kind might at first embrace the epistocracy, but then rebel once it’s clear that the epistocrats aren’t ruling in the favored ways.

The point here is that epistocracy among a population comprised mostly of hooligans likely will be unstable. Yet part of what makes for a well-performing political order is stability, and stability is a matter not only of the substantive justice of the policies that the governing body implements, but also of the ways in which the policies — and the bodies that make them — are generally perceived. Brennan may be correct to hold that hooligans ruin democracy. But that’s because hooligans ruin everything, including epistocracy.

A good deal of democratic theory is devoted to devising ways to transform hooligans into Vulcans. Brennan provides reasons for thinking that this project is unlikely to succeed. He proposes an epistocratic departure from democracy that aims to empower the Vulcans by constraining or eliminating the power of the hooligans and the hobbits. But this strategy invites social instability. Perhaps the better response is to sustain democratic political conditions but create ways to transform hooligans into hobbits?

February 5, 2020

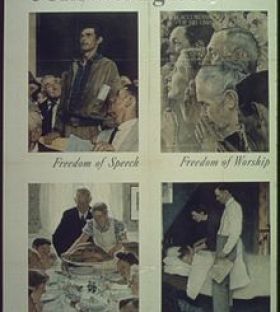

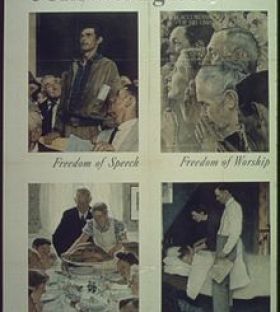

Understanding Freedom: Freedom and the Human Spirit (Conclusion)

© Robert Orwell Hand – (Reprinted with Permission) https://understandingthings.net/2019/11/01/understanding-freedom-part-v-freedom-and-politics-cont

© Robert Orwell Hand – (Reprinted with Permission) https://understandingthings.net/2019/11/01/understanding-freedom-part-v-freedom-and-politics-cont

To believe in the ideal of freedom for all, you must believe, generally speaking, that people can be trusted with power. Not, that is, with power over the lives of others—which invites and, when absolutized, assures corruption—but with power over their own lives, both individually and collectively. Another term for that individual and collective exercise of power is self-government.

This democratic belief in freedom for all cannot confine this self-governing power to just some people. Not just certain kinds of people. It views the power of self-government as the birthright of the people.

This does not require that people be perfect, just that they can (and that many do) learn and grow (which highlights the necessity of public schooling that educates students in American history rather than in American mythology). And it requires that rather than positioning themselves over others, leaders operate among the people. Which is to say that democratic leadership functions by example and persuasion rather than by authority and coercion. (Where coercive authority may be necessary as a last resort, it must always be justified as such in democratic terms). ,

This faith in the people is reinforced by a consideration of the only alternative to people power: allowing power to reside and remain (as it, of course, already does) in the hands of the powerful few. And this is the chief difference between what are, in political terms, alternatively called “the Right” and “the Left,” and why this distinction, properly understood, should and must be preserved.

To be on “the Right” is to believe that people in general cannot be allowed, because they are fundamentally unqualified, to exercise power and, therefore, to be trusted with power over their own lives (in any but a rhetorical sense). Consequently, people need “leaders” who control them—whether kings or lords or masters or bishops or bosses or officials—by making the decisions for them that they cannot be trusted to make for themselves. Thus, the conservative position has always been to defend the monarchy against the republic, the aristocracy against the commoners, the freedom of the powerful few against the freedom of all, so as to uphold the way things are as determined by the powers that be. And so much for democracy.

To be on “the Left,” in contrast, is to believe that people, despite their myriad imperfections and fallibilities, are in a far better position to decide for themselves what they need and want and how to cooperatively go about getting it, both individually and collectively, than any one or any group that would claim the right and, therefore, the freedom/power to rule over them. Which is the essence of democracy.

Your understanding of freedom may, finally, rest on how you interpret Jefferson’s famous assertion that “all men are created equal.” By “men,” did he and the others who signed the Declaration of Independence, refer only to “all” white, land-owning males (who were, after all, the only ones who were originally treated as possessing equal rights)?

If so, those who consciously believe that (or just unconsciously act like) whites are the supreme “race,” that males are superior to females, and/or that the material success of America and its owning/ruling class is a “blessing” bestowed by God on those who deserve it, may perhaps content themselves that they are in line with the “original intent” of the founders: that freedom was intended only for people like themselves (who, if not already there, nurse the hope that they will one day ascend to owning-class status). And that, therefore, talk of the equality of freedom for all is unnatural, running counter to the intended reality of things (which seems, judged by the effects of their rulings, to be the sentiment of the “originalists” who now form the majority of the U.S. Supreme Court, the only totally undemocratic—that is, unelected—branch of the U.S. government).

At the end of the 19th century—30-some years after the Emancipation Proclamation and the subsequent end of chattel slavery—a great debate ensued in the U.S. Congress regarding whether or not the Declaration’s assertion of the ideal of the equality of all human beings—of freedom for all—realistically applied to the non-white islanders of the Philippines and Puerto Rico and Cuba, and whether or not the Declaration’s demand for self-government necessarily excluded the U.S. from competition with the national powers of Europe for imperial expansion across the globe.

As historian Stephen Kinzer points out, avowed American imperialist and future U.S. President Teddy Roosevelt led the political charge for war with Spain (as well as the cavalry charge up San Juan Hill) to “liberate” Cuba, along with those other Spanish colonies. And, after the American victory over Spain, he led the charge for the U.S. annexation of those same colonies; this had only recently been done with the erstwhile nation of Hawaii (which eventually, of course, became the 50th state).

Anti-imperialists, like Mark Twain, viewed this movement as an unconstitutional betrayal of America’s founding principles, and they issued all-too-prophetic warnings that the path to empire would inevitably lead the U.S. into militarism and oligarchy.

But those eager to expand American territories (and markets) beyond the continental borders of the U.S. made the undeniable argument that U.S. expansion across the North American continent had always consisted of seizing the lands of peoples perceived to be inferior: specifically, American Indians and Mexicans, non-white and, therefore, considered unfit for self-government because, for all intents and purposes, less than fully human. For U.S. imperialists, it was simply a logical extension of the mythical doctrine of Manifest Destiny for the U.S. to accept its God-given role of bringing the American version of “freedom and democracy” to the rest of the world, whether the rest of the world wanted it or not. (After all, George Washington himself had called the newly-formed United States “a nascent empire” and, later, Thomas Jefferson called America “an Empire of Liberty.”)

And so it was that the U.S. launched its capitalist empire overseas, setting the stage for what became known as “the American Century” (and increasingly reducing talk of the U.S. being a “democracy” to merely a rhetorical flourish, necessary to appease and confuse the general population).

Historically, the “freedom and democracy” that the U.S. government has tried to spread, both diplomatically and militarily, throughout the world is the capitalist version thereof. The capitalist version of “freedom” is the unhindered power of capitalists to expropriate resources and exploit labor and expand markets in their own and in whatever other countries they choose. And the capitalist version of “democracy” is a political system legitimized by—and, as far as the people are concerned, virtually reduced to—voting, wherein voters vote for candidates who are allowed (by being financed by the powers that be) to run for office because they represent the interests of the U.S. capitalists and their international allies, the oligarchs who virtually run the governments of their own countries. (The democratic-alternative model of independent, small-donor-financed political campaigns pioneered by Bernie Sanders is—like so much of Sanders’ approach to politics—the exception that proves the rule.)

When relatively progressive leaders manage, against the odds, to ascend to political power in other nations, threatening the interests of capital by moving to use resources and labor and markets, to whatever degree manageable, to build more educated, healthy and prosperous societies, the U.S. government demonizes them (through the mouthpiece of the U.S. corporate media) as “corrupt dictators,” cripples their national economies with sanctions, and when that doesn’t work, directs CIA-engineered military coups to effect “regime change” (20th and 21st century examples having included Iran, Guatemala, Chile, and Honduras, with Venezuela the current target).

And this version of “freedom and democracy” accords perfectly with the view that the “all men [who] are created equal” are the white, big-business-and-land-owning capitalists of America.

If, however, “all men”—as it has progressively been understood throughout American history—is the founders’ archaic, gender-neutral representation of all human beings—not only Americans but all members of the human race—then the way things are as determined by the powers that be is exposed as un-American, at least as far as the nobler instincts of the founding fathers enshrined in the Declaration of Independence are concerned. And this expansive and inclusive sense of “all men” laid the foundation for a radical American progressivism in the interest of freedom for one and all.

So, thinking Americans are faced with a clear choice about how to regard their common history. Perhaps what have been called America’s original sins—African-American slavery and Native-American genocide—were not really sins at all but, to the contrary, part of the working out of a divine plan, or at worst, necessary evils in the building of “America”; in that case, the return to (or the maintenance of) America’s imperial greatness is the right goal.

If, however, American greatness is not a matter of the “freedom” of the world’s only superpower to impose its will (for better or, as has typically been the case, for worse) on the rest of the world, if American greatness is, instead, a matter of progress toward the as-yet-far-from-attained goal of freedom for all in America and in the rest of the world, then a national reassessment of American history is long overdue.

The aftermath of this historical reassessment would unavoidably result in recognizing with deep regret the moral darkness of slavery and genocide out of which “America” emerged. This recognition would, reasonably and appropriately, result in the U.S. government’s investing in the socio-economic-and-political empowerment of the African and Native American communities against whom these national sins were committed (and who continue to suffer under their legacy).

And, as far as African Americans are concerned, this would be part and parcel of the empowerment of American workers in general. As progressive political scientist Adolph Reed, Jr., points out, all movement toward the empowerment of American workers would disproportionately benefit African Americans, the vast majority of whom are members of the American working class and make up a sizeable part of it. Only as all members of the U.S. working class—of whatever color or gender—see themselves as aligned not against one another but against the powers that be, will they work together for their own and each other’s empowerment in the interest of freedom for all.

Regarding the American Indian community, the appropriate historical reassessment can only mean the restoration to tribal sovereignty of native nations over their reservation lands and resources, including the economic support necessary to develop their economies and to protect and preserve the water they share with the rest of America. Native communities have led the way in the 21st century in standing against the ongoing environmental assaults perpetrated by the fossil fuel industry, which continues to enjoy the aggressive (as in violent) support of both the U.S. and state governments. Only as an increasing number of Americans in general identify with the struggles of native communities against the powers that be, embracing those struggles as their own, will justice belatedly come to what’s left of native America.

Conservatives, of course, would cry out that the U.S. government cannot possibly afford the necessary funds for working-class and tribal economic empowerment (not to mention reparations of any kind), just as they moan and groan about the unaffordability of Social Security and Medicare and Medicaid. And this, even as they continually form and pass legislation that spends trillions of taxpayer dollars on American wars all over the planet and on tax cuts for the tiny minority of the wealthiest and most powerful Americans.

The grim reality is that since World War II, the financial priority of the powers that be, represented by their conservative and moderate political proxies, has been the funding of the military-industrial complex (in Eisenhower’s original, unedited formulation: the military-industrial-congressional complex) in the interest of the maintenance and expansion of the American empire.

And in the wake of the 1960s, due to the threat to empire of the civil-rights and anti-war movements (which threatened to redirect significant funding away from “defense” spending to the economic development of the African American community and, subsequently, other minority groups and the poor in general), the powers that be have responded by constructing a prison-industrial complex. The emergence of mass incarceration—the U.S. consisting of 5% of the world’s population and 25% of the world’s prisoners—has seen the virtual criminalization of non-whiteness, naturally accompanied by the criminalization of poverty and immigration. And this has set the stage for the increasing criminalization of dissent, targeting any grassroots movements for social and economic and environmental justice that dare to get out on the streets. (Witness the ruthless police repression of, among other examples, the Occupy Wall Street movement in 2011 and of the Standing Rock Lakota and allied opposition to the Dakota Access Pipeline in 2016.)

In sum, the U.S. military-industrial complex represents the assault of the powers that be on the possibilities of freedom in the rest of the world while the U.S. prison-industrial complex—along with increasingly militarized local police departments—represents their assault on the remaining possibilities for the freedom of American citizens themselves. All, of course, in the name of preserving and spreading freedom and democracy.

Only with an honest, sincere, and widespread acknowledgement of the history of unfreedom in America can there emerge a realistic prospect for progress toward freedom for one and all. And that is because only this kind of reassessment of the unfreedom in America’s past will awaken a realization of the alarming degree to which the scales have been so heavily tipped against freedom in America’s present.

But the emergence of a realistic prospect of freedom for all in America will not come without furious resistance on the part of the powers that be.

In 1984, George Orwell’s dystopian vision of the disappearance of freedom from the face of the earth (freedom being the first casualty of the war on truth), O’Brien, the grand inquisitor of “the Party,” asks Winston, the now-exposed dissenter, how “one asserts power over another.” Winston replies, “By making him suffer.” O’Brien then explains why this is, indeed, the case: “Unless he is suffering, how can you be sure that he is obeying your will and not his own? Power is in inflicting pain and humiliation. Power is in tearing human minds to pieces and putting them together again in new shapes of your own choosing.”

Through O’Brien, Orwell describes not what power must be but what power must become in a state in which the people become permanently powerless. When power becomes the exclusive and permanent possession of the few over the many, its features are distorted and misshapen in monstrous ways because that is precisely what is necessary to maintain the status quo: the permanent and absolute subservience of the powerless.

O’Brien’s and Winston’s assessment of how one asserts power over another is necessarily the case when the one represents the powerful few whose permanent possession of power depends on the permanent powerlessness of another, that is, the many, who can’t be allowed to obey for any ulterior motives—whether in the hope of eventually ascending to the status of the chosen few, or merely in the hope of being left alone and unmolested—because in either case they remain a potential threat. For the powers that be to secure their hold on all the power, the many must obey because they lack both the power and the will to disobey, and this requires their suffering.

According to Neil Postman (in his 1986 book, Amusing Ourselves to Death), among others, Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (written in 1931)—a vision of the future according to which humans give up their freedom for the physical and mental comfort of material affluence and drug-induced euphoria—seemed more prophetic of cultural and political developments in the late 20th century than Orwell’s more darkly and brutally dystopian 1984 (written in 1948). As long as the New Deal and Great Society programs of the mid-to-late twentieth century kept the capitalist beast, at least to some extent, at bay—meaning that the agenda of the powers that be had necessarily to be less obvious, more covert—this seemed an accurate perception. And it certainly continues to be the case that the desire to be perpetually entertained distracts many Americans (at least those whose heads are still economically above water) from concerns about threats (even from the truthlessness of Trump) to their freedom.

In the twenty-first century, though (particularly, in the wake of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, and the subsequent “War on Terror”), a case for the superior prescience of 1984 seems quite arguable. While Orwell did not foresee the digital revolution and the way it would make information available to the many—even despite the dis-informational agenda of the powers that be (which may nevertheless yet be realized via the state-enforced end of internet neutrality)—he certainly foresaw the war on truth, as well as on privacy by the surveillance state, personified by “Big Brother”; he also foresaw the current reality of endless war, which consumes so many billions of tax-payer dollars that could—but won’t—be spent on the healthcare and housing and education and infrastructure that would speed progress toward the goal of freedom for all.

Orwell apparently believed that as early as the beginning of the twentieth century, technology had advanced to the point that a relatively equal standard of living for all the peoples of the earth was a realizable goal. However, in the internal world of 1984, in the wake of World War II and potential nuclear devastation, the few at the top of the hierarchical organizations of the world’s societies have devised a strategy whereby their power will be permanently preserved via endless war (along with linguistic mind control and mass surveillance).

The totalizing mind-control imposed by “the Party” of 1984 on its members is not as far removed as it may seem from the ongoing project of today’s corporate powers that be: to infuse capitalism’s market values and belief system into people’s everyday thinking via the corporatization of the mainstream media and, increasingly, the internet. The violence perpetrated by “the Party” of 1984 on its members to disable their freedom of thought—that is, people’s ability to think critically and creatively—has been rendered virtually unnecessary by at least two factors: first, the near monopolization and corporatization of communication by Facebook, Amazon, Google and Apple; and second, the mind-numbing and consciousness-shrinking effects of standardized testing (by means of its demand for comprehensionless-reading and communicationless-writing) on the public education system.

Nevertheless, the mastery of the powers that be at “tearing human minds to pieces and putting them together again in new shapes of your own choosing” is on display in America today by means of an economic violence (now called “austerity”) that is only somewhat less brutal, in its deprivation of working people’s basic necessities, than the physical violence of 1984. (Witness the passive compliance, and in some cases active complicity, of the growing mass of have-nots with their corporate overlords in the face of income inequality unmatched since just before the Great Depression, though promising signs of grassroots resistance are emerging.)

Clearly, 1984 depicts Orwell’s perception of the communist totalitarianism of mid-20th-century Stalinism, but he was equally as wary of the potential capitalist totalitarianism that has since been emerging in the form of neoliberalism. In a pre-1984 book review of The Road to Serfdom, by Friedrich Hayek, the influential Austrian pioneer of unregulated capitalism (in which book Hayek sounds the conservative alarm regarding the economics of communist totalitarianism), Orwell suggested that unregulated capitalism would result in “a tyranny probably worse [than communist totalitarianism], because more irresponsible, than that of the State.” More “irresponsible” because its power is directed exclusively toward the priority of profit at the expense of all else, from individual human rights to the planetary survival of the human race.

And this capitalist totalitarianism is currently leaving even the possibility of freedom for any but the powers that be in jeopardy.

Which suggests an answer to 1984’s enduring question as to why the powerful of the world should be so adamantly and unalterably opposed to a human equality that technology has now made theoretically realizable. That answer: As long as even a remote possibility of freedom for all remains—the possibility of an equal distribution of power to the powerless and, thus, the fall of the power elite—then the status quo, the position of the powerful few, will remain uncertain. And concentrated power craves certainty, because the powers that be always feel—albeit often unconsciously—how tentative and contingent their power really is. And not least, how incompetent they are at predicting the future. Consequently, any threat of equality, of people-power—of the possibility of freedom for all—is intolerable and must be ground to dust.

“I’ll tell you what freedom is to me,” proclaimed the late, great African American singer-songwriter and civil rights activist Nina Simone: “No fear!”

The effect of all the external restraints on people-power imposed by the powers that be—from school-and-church-and-media indoctrination to voter disenfranchisement, from patriarchy to homophobia, from worker and consumer exploitation to unemployment, imprisonment and execution—is that those external restraints are internalized in the form of fear. Fear itself is the greatest restraint on people power because it starves and strangles the human spirit of resistance.

Freedom, then, is not merely the absence of external restraints after all, but much further and deeper, freedom is the absence of the internalized restraint of fear—fear of some form of punishment for exercising the power to be (which means, by extension, the power to express) yourself, especially in unauthorized and, therefore, unacceptable ways. This is the fear that is bred into the soul by the way things are as orchestrated by the powers that be.

When understood as the unrestrained, unhindered power of all human beings to be themselves, individually and collectively (respecting and protecting that self-governing power for all), freedom reveals itself to be a spiritual thing (which is not to say, a religious thing).

The ideal of freedom for all assumes that below the physical-social-economic-political surface of human existence dwells a human spirit—a mental and moral energy—that unites all human beings in a universal sister-and-brother-and-other-hood. And that in the face of the fear-instilling, fear-inducing external restraints that the powerful impose on the powerless, a human spirit exists within each of us that can resist, that can somehow refuse to allow fear to modify our behavior into compliance with and subservience to the powers that be, and instead, can act in concert with others to transform the way things are.

And if so, freedom is the self-claimed thing that unleashes the power to realize the twin human aspirations to individuality and community: the freedom from fear that releases the power to love both yourself and your neighbor as yourself.

And this neighbor-love that begins with and depends on self-love—even as the words, “You shall love your neighbor as yourself,” have been virtually emasculated by religious and humanitarian rhetoric—is the spiritual power that arms, however haltingly, the one who has tasted and is growing into freedom, and that aims at the goal of freedom for all. This power of neighbor-as-self-love is the spiritual dynamic that energizes the politics of people-power from the inside out, unifying the people—”the 99%”—by disarming our addictions to the tribalism, suspicion, mistrust, rivalry and bigotry—in short, the fear—that divides the human animal into herds, civil society into, at best, peacefully co-existing and, at worst, warring factions.

The absence of progress toward the ideal of freedom for all does not mean that the way things are stays the same, socioeconomically and politically, for the people of the world: great for the powerful few and relatively good for some of the many, while ranging from relatively to thoroughly bad to absolutely horrific for most of them.,

Despite having determined, for all intents and purposes, the shape and color of socio-political-economic-and-environmental reality, the powers that be are never content with the way things are. While accepting temporary setbacks when they must, they are always determined to take full possession of whatever is left, to make full use of the available technology to have it all. As Adam Smith (ironically, one of capitalism’s economic heroes) scornfully wrote of them in 1776, “All for ourselves and nothing for other people, seems, in every age of the world, to have been the vile maxim of the masters of mankind.” And this, no matter how unsustainable for human existence it may ultimately and finally (and more and more imminently) prove to be.

It may not be too late to reverse the disappearing of freedom from the face of the earth, but only if and as the powers that be are confronted by the power of the people, claiming the human political-and-spiritual right to freedom for one and all—the unhindered, unrestrained power of neighbor-as-self-love—as their own: the freedom from fear to transform the way things are into a human reality that can work for one and all.

Understanding Freedom: Chap 4 (Conclusion) – Freedom and the Human Spirit

© Robert Orwell Hand – (Reprinted with Permission) https://understandingthings.net/2019/11/01/understanding-freedom-part-v-freedom-and-politics-cont

© Robert Orwell Hand – (Reprinted with Permission) https://understandingthings.net/2019/11/01/understanding-freedom-part-v-freedom-and-politics-cont

To believe in the ideal of freedom for all, you must believe, generally speaking, that people can be trusted with power. Not, that is, with power over the lives of others—which invites and, when absolutized, assures corruption—but with power over their own lives, both individually and collectively. Another term for that individual and collective exercise of power is self-government.

This democratic belief in freedom for all cannot confine this self-governing power to just some people. Not just certain kinds of people. It views the power of self-government as the birthright of the people.

This does not require that people be perfect, just that they can (and that many do) learn and grow (which highlights the necessity of public schooling that educates students in American history rather than in American mythology). And it requires that rather than positioning themselves over others, leaders operate among the people. Which is to say that democratic leadership functions by example and persuasion rather than by authority and coercion. (Where coercive authority may be necessary as a last resort, it must always be justified as such in democratic terms). ,

This faith in the people is reinforced by a consideration of the only alternative to people power: allowing power to reside and remain (as it, of course, already does) in the hands of the powerful few. And this is the chief difference between what are, in political terms, alternatively called “the Right” and “the Left,” and why this distinction, properly understood, should and must be preserved.

To be on “the Right” is to believe that people in general cannot be allowed, because they are fundamentally unqualified, to exercise power and, therefore, to be trusted with power over their own lives (in any but a rhetorical sense). Consequently, people need “leaders” who control them—whether kings or lords or masters or bishops or bosses or officials—by making the decisions for them that they cannot be trusted to make for themselves. Thus, the conservative position has always been to defend the monarchy against the republic, the aristocracy against the commoners, the freedom of the powerful few against the freedom of all, so as to uphold the way things are as determined by the powers that be. And so much for democracy.

To be on “the Left,” in contrast, is to believe that people, despite their myriad imperfections and fallibilities, are in a far better position to decide for themselves what they need and want and how to cooperatively go about getting it, both individually and collectively, than any one or any group that would claim the right and, therefore, the freedom/power to rule over them. Which is the essence of democracy.

Your understanding of freedom may, finally, rest on how you interpret Jefferson’s famous assertion that “all men are created equal.” By “men,” did he and the others who signed the Declaration of Independence, refer only to “all” white, land-owning males (who were, after all, the only ones who were originally treated as possessing equal rights)?

If so, those who consciously believe that (or just unconsciously act like) whites are the supreme “race,” that males are superior to females, and/or that the material success of America and its owning/ruling class is a “blessing” bestowed by God on those who deserve it, may perhaps content themselves that they are in line with the “original intent” of the founders: that freedom was intended only for people like themselves (who, if not already there, nurse the hope that they will one day ascend to owning-class status). And that, therefore, talk of the equality of freedom for all is unnatural, running counter to the intended reality of things (which seems, judged by the effects of their rulings, to be the sentiment of the “originalists” who now form the majority of the U.S. Supreme Court, the only totally undemocratic—that is, unelected—branch of the U.S. government).

At the end of the 19th century—30-some years after the Emancipation Proclamation and the subsequent end of chattel slavery—a great debate ensued in the U.S. Congress regarding whether or not the Declaration’s assertion of the ideal of the equality of all human beings—of freedom for all—realistically applied to the non-white islanders of the Philippines and Puerto Rico and Cuba, and whether or not the Declaration’s demand for self-government necessarily excluded the U.S. from competition with the national powers of Europe for imperial expansion across the globe.

As historian Stephen Kinzer points out, avowed American imperialist and future U.S. President Teddy Roosevelt led the political charge for war with Spain (as well as the cavalry charge up San Juan Hill) to “liberate” Cuba, along with those other Spanish colonies. And, after the American victory over Spain, he led the charge for the U.S. annexation of those same colonies; this had only recently been done with the erstwhile nation of Hawaii (which eventually, of course, became the 50th state).

Anti-imperialists, like Mark Twain, viewed this movement as an unconstitutional betrayal of America’s founding principles, and they issued all-too-prophetic warnings that the path to empire would inevitably lead the U.S. into militarism and oligarchy.

But those eager to expand American territories (and markets) beyond the continental borders of the U.S. made the undeniable argument that U.S. expansion across the North American continent had always consisted of seizing the lands of peoples perceived to be inferior: specifically, American Indians and Mexicans, non-white and, therefore, considered unfit for self-government because, for all intents and purposes, less than fully human. For U.S. imperialists, it was simply a logical extension of the mythical doctrine of Manifest Destiny for the U.S. to accept its God-given role of bringing the American version of “freedom and democracy” to the rest of the world, whether the rest of the world wanted it or not. (After all, George Washington himself had called the newly-formed United States “a nascent empire” and, later, Thomas Jefferson called America “an Empire of Liberty.”)

And so it was that the U.S. launched its capitalist empire overseas, setting the stage for what became known as “the American Century” (and increasingly reducing talk of the U.S. being a “democracy” to merely a rhetorical flourish, necessary to appease and confuse the general population).

Historically, the “freedom and democracy” that the U.S. government has tried to spread, both diplomatically and militarily, throughout the world is the capitalist version thereof. The capitalist version of “freedom” is the unhindered power of capitalists to expropriate resources and exploit labor and expand markets in their own and in whatever other countries they choose. And the capitalist version of “democracy” is a political system legitimized by—and, as far as the people are concerned, virtually reduced to—voting, wherein voters vote for candidates who are allowed (by being financed by the powers that be) to run for office because they represent the interests of the U.S. capitalists and their international allies, the oligarchs who virtually run the governments of their own countries. (The democratic-alternative model of independent, small-donor-financed political campaigns pioneered by Bernie Sanders is—like so much of Sanders’ approach to politics—the exception that proves the rule.)

When relatively progressive leaders manage, against the odds, to ascend to political power in other nations, threatening the interests of capital by moving to use resources and labor and markets, to whatever degree manageable, to build more educated, healthy and prosperous societies, the U.S. government demonizes them (through the mouthpiece of the U.S. corporate media) as “corrupt dictators,” cripples their national economies with sanctions, and when that doesn’t work, directs CIA-engineered military coups to effect “regime change” (20th and 21st century examples having included Iran, Guatemala, Chile, and Honduras, with Venezuela the current target).

And this version of “freedom and democracy” accords perfectly with the view that the “all men [who] are created equal” are the white, big-business-and-land-owning capitalists of America.

If, however, “all men”—as it has progressively been understood throughout American history—is the founders’ archaic, gender-neutral representation of all human beings—not only Americans but all members of the human race—then the way things are as determined by the powers that be is exposed as un-American, at least as far as the nobler instincts of the founding fathers enshrined in the Declaration of Independence are concerned. And this expansive and inclusive sense of “all men” laid the foundation for a radical American progressivism in the interest of freedom for one and all.

So, thinking Americans are faced with a clear choice about how to regard their common history. Perhaps what have been called America’s original sins—African-American slavery and Native-American genocide—were not really sins at all but, to the contrary, part of the working out of a divine plan, or at worst, necessary evils in the building of “America”; in that case, the return to (or the maintenance of) America’s imperial greatness is the right goal.

If, however, American greatness is not a matter of the “freedom” of the world’s only superpower to impose its will (for better or, as has typically been the case, for worse) on the rest of the world, if American greatness is, instead, a matter of progress toward the as-yet-far-from-attained goal of freedom for all in America and in the rest of the world, then a national reassessment of American history is long overdue.

The aftermath of this historical reassessment would unavoidably result in recognizing with deep regret the moral darkness of slavery and genocide out of which “America” emerged. This recognition would, reasonably and appropriately, result in the U.S. government’s investing in the socio-economic-and-political empowerment of the African and Native American communities against whom these national sins were committed (and who continue to suffer under their legacy).