John G. Messerly's Blog, page 49

April 28, 2020

Sleep and Depression in Older Persons

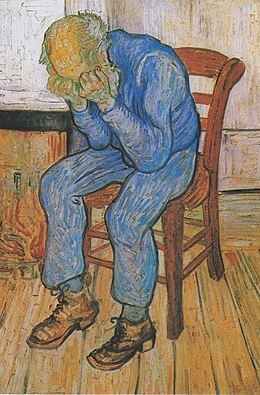

Vincent van Gogh’s 1890 painting Sorrowing old man (‘At Eternity’s Gate’)

Vincent van Gogh’s 1890 painting Sorrowing old man (‘At Eternity’s Gate’)

Depression is a serious problem. While its causes are complicated and variable, sleep deprivation is commonly connected with depression. In fact, Harvard Medical School says that sleep deprivation can seriously affect all aspects of mental health. (Lack of sleep obviously has serious consequences for your physical health too.)

The connection between lack of sleep and depression is especially prevalent among older persons. I found a detailed discussion of the connection in this guide. It begins “Depression is exacerbated by sleeplessness and vice versa. Left untreated these issues can worsen and cause further health concerns. Major depressive disorder is not a normal part of aging.”

The guide focuses primarily on depression in older persons but contains a lot of good information for everyone. And it goes into some detail on the following topics:

1) Effects of depression and poor sleep

2) Organizations for mental health

3) Care needs for sleep issues and depression

4)Supporting a loved one with depression

5) Finding the right care provider

6) Sleep issues and depression FAQs

If you’re worried about this issue, either for yourself or someone you love, I hope this helps.

________________________________________________________________________

Disclaimer – I’m am not associated with Family Assets Group that published the above guide nor do I know enough to either recommend or not recommend them.

April 26, 2020

Yuval Harari Issues Warning at Davos 2020

Davos, Switzerland

Davos, Switzerland

At the January World Economic Forum Annual Meeting (Davos 2020), Yuval Harari, the historian, philosopher, and best-selling author of Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind[image error], and Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow[image error], issued a dire warning about the future.

Harari outlined three existential threats facing humanity in this century—nuclear war, ecological collapse, and technological disruption. Regarding the first two as familiar, he focuses on the lesser-known threat posed by technological disruption.

…we hear so much about the enormous promises of technology – and these promises are certainly real. But technology might also disrupt human society and the very meaning of human life in numerous ways, ranging from the creation of a global useless class to the rise of data colonialism and of digital dictatorships.

1) upheavals on the social and economic level

Automation will eliminate millions of jobs. Moreover, truckers won’t be willing or able to become software engineers or the personal trainers of software engineers. It will be increasingly hard for people not to become irrelevant and form a useless class to be exploited by a powerful elite.

2) unprecedented inequality not just between classes but also between countries

The country or countries that win the artificial intelligence race will be able to dominate and exploit everyone else. Countries that don’t keep up will either go bankrupt or become data-colonies. “When you have enough data you don’t need to send soldiers, in order to control a country.”

3) the rise of digital dictatorships, that will monitor everyone all the time

He states this danger in the form of a simple equation, which “might be the defining equation of life in the twenty-first century”

B x C x D = AHH!

This means that biological knowledge multiplied by computing power multiplied by data equals the ability to hack humans … ahh. “If you know enough biology and have enough computing power and data, you can hack my body and my brain and my life, and you can understand me better than I understand myself.” We are increasingly hackable. (This explains why people are so easily manipulated to vote against their own interests.)

This power to hack humans can be used for good—provide better healthcare—or it may lead to new kind of totalitarianism. The regime will monitor your heart and brain and you can clap and smile for the great leader or end up in the gulag … or worse. And, as Harari points out, being rich and powerful doesn’t protect you. So it is in everyone’s self-interest to prevent digital dictatorships. (Politicians and billionaires who enthusiastically support corrupt leaders, in the hope of sharing in the wealth and power, forget about purges!)

If successful “the ability to hack humans might still undermine the very meaning of human freedom.” Humans already increasingly rely on AI to make their decisions. Facebook tells us what to believe, Google tells us what’s true, Netflix tells us what to watch, Amazon tells us what to buy. Soon algorithms may tell us what work we should do and who we should marry. Already the world is so complex that few if any human minds understand how it works. If our decisions are made for us what then is the meaning of our lives?

… infotech and biotech are now giving politicians the means to create heaven or hell … that’s a very dangerous situation. If we fail to conceptualize the new heaven quickly enough, we might be easily misled by naïve utopias. And if we fail to conceptualize the new hell quickly enough, we might find ourselves entrapped there with no way out.

4) technology might also disrupt our biology

AI and biotech will alter, not just our economy, politics, and philosophy, but also our biological nature as we learn to reengineer life. This power holds both promise and peril but avoiding the worst scenarios demands global cooperation.

5) All three existential challenges are global problems that demand global solutions

The threat of nuclear war, ecological collapse, and technological disruption demand global cooperation. No country can stop nuclear war, save the environment, or regulate advanced technologies by themselves. However, just when we need such cooperation, many world leaders are rejecting it.

Leaders like the US president tell us that there is an inherent contradiction between nationalism and globalism, and that we should choose nationalism and reject globalism.

This is a dangerous mistake. No contradiction exists between nationalism and globalism because nationalism isn’t about hating foreigners—nationalism is about loving your compatriots. In the twenty-first century, in order to protect the safety and the future of your compatriots, you must cooperate with foreigners.

This doesn’t necessitate establishing global government but being committed to global rules. A simple model to understand this, Harari says, is the World Cup. People don’t abandon their nationalism but agree to play by the rules—that’s globalism in action. We need countries to work together to prevent ecological collapse, regulate dangerous technologies, and reduce global inequality. This may be difficult but it isn’t impossible.

Consider that for almost all of human history we under the constant threat of war. But in the last few decades “We have built the rule-based liberal global order, that despite many imperfections, has nevertheless created the most prosperous and most peaceful era in human history.” What an achievement.

We are now living in a world in which war kills fewer people than suicide, and gunpowder is far less dangerous to your life than sugar. Most countries – with some notable exceptions like Russia – don’t even fantasize about conquering and annexing their neighbors.

The problem, as Harari sees it, is that we have become complacent and are careless.

The global order is now like a house that everybody inhabits and nobody repairs. It can hold on for a few more years, but if we continue like this, it will collapse – and we will find ourselves back in the jungle of omnipresent war.

We have forgotten what it’s like, but believe me as a historian – you don’t want to be back there. It is far, far worse than you imagine.

Yes, our species has evolved in that jungle and lived and even prospered there for thousands of years, but if we return there now, with the powerful new technologies of the twenty-first century, our species will probably annihilate itself.

April 23, 2020

George Packer “We Are Living in a Failed State”

Declaration of Independence by John Trumbull

Declaration of Independence by John Trumbull

If you read one short article about the state of contemporary America it should be George Packer’s “We Are Living in a Failed State: The coronavirus didn’t break America. It revealed what was already broken” in The Atlantic. The article’s subtitle expresses it main theme. The article captures our attention in its very first paragraphs.

When the virus came here, it found a country with serious underlying conditions, and it exploited them ruthlessly. Chronic ills—a corrupt political class, a sclerotic bureaucracy, a heartless economy, a divided and distracted public—had gone untreated for years …

The crisis demanded a response that was swift, rational, and collective. The United States reacted instead like Pakistan or Belarus—like a country with shoddy infrastructure and a dysfunctional government whose leaders were too corrupt or stupid to head off mass suffering. The administration squandered two irretrievable months to prepare. From the president came willful blindness, scapegoating, boasts, and lies. From his mouthpieces, conspiracy theories and miracle cures. A few senators and corporate executives acted quickly—not to prevent the coming disaster, but to profit from it. When a government doctor tried to warn the public of the danger, the White House took the mic and politicized the message.

We live in a country without a national plan, writes Packer, where families, schools, and offices were left to decide on their own whether to shut down and take shelter. Test kits, masks, gowns, and ventilators were in short supply, and when governors were forced to plead for them, price gouging and corporate profiteering resulted. Poor countries and the UN sent humanitarian aid to the world’s richest power. Naturally, Trump saw the crisis entirely in personal and political terms, abandoning the nation to prolonged disaster.

Packer compares the current crisis to two others to hit America in the 21st century. When the USA was struck on September 11, 2001 “people in the rural heartland did not see New York as an alien stew of immigrants and liberals that deserved its fate, but as a great American city that had taken a hit for the whole country.” But partisan politics and the Iraq War created bitterness toward the political class that is still with us.

The financial crisis in 2008 made things even worse. Bankers kept their fortunes and soon were back to business as usual, but many in the middle and lower classes never recovered. Inequality continued to grow and the working class was left further behind. As a result, both parties lost credibility and the harbinger of the new populism was “Sarah Palin, the absurdly unready vice-presidential candidate who scorned expertise and reveled in celebrity. She was Donald Trump’s John the Baptist.”

Trump campaigned as an opponent of the Republican establishment, but soon the conservative political class and Trump realized they “shared a basic goal: to strip-mine public assets for the benefit of private interests.” No one cared if the Trump regime couldn’t govern or if it destroyed national civic life—as long as they all got richer.

The federal government Trump inherited had been defunded by years of right-wing ideological assault. Trump continued the assault by

… destroying the professional civil service. He drove out some of the most talented and experienced career officials, left essential positions unfilled, and installed loyalists as commissars over the cowed survivors, with one purpose: to serve his own interests. His major legislative accomplishment, one of the largest tax cuts in history, sent hundreds of billions of dollars to corporations and the rich. The beneficiaries flocked to patronize his resorts and line his reelection pockets. If lying was his means for using power, corruption was his end.

This was the American landscape that lay open to the virus: in prosperous cities, a class of globally connected desk workers dependent on a class of precarious and invisible service workers; in the countryside, decaying communities in revolt against the modern world; on social media, mutual hatred and endless vituperation among different camps; in the economy, even with full employment, a large and growing gap between triumphant capital and beleaguered labor; in Washington, an empty government led by a con man and his intellectually bankrupt party; around the country, a mood of cynical exhaustion, with no vision of a shared identity or future.

The virus might have united Americans but it did not. Instead, it exposed the inequality we’ve tolerated for so long. Almost no one could get tests yet the wealthy and connected were somehow able to get tested, despite many showing no symptoms. And who turns out to be essential workers? Not wall street executives or financiers but

Mostly people in low-paying jobs that require their physical presence and put their health directly at risk: warehouse workers, shelf-stockers, Instacart shoppers, delivery drivers, municipal employees, hospital staffers, home health aides, long-haul truckers. Doctors and nurses are the pandemic’s combat heroes, but the supermarket cashier with her bottle of sanitizer and the UPS driver with his latex gloves are the supply and logistics troops who keep the frontline forces intact. In a smartphone economy that hides whole classes of human beings, we’re learning where our food and goods come from, who keeps us alive.

Who then are the non-essential workers?

One example is Kelly Loeffler, the Republican junior senator from Georgia, whose sole qualification for the empty seat that she was given in January is her immense wealth. Less than three weeks into the job, after a dire private briefing about the virus, she got even richer from the selling-off of stocks … Loeffler’s impulses in public service are those of a dangerous parasite. A body politic that would place someone like this in high office is well advanced in decay.

Another example is Jared Kushner.

… Kushner has been fraudulently promoted as both a meritocrat and a populist. He was born into a moneyed real-estate family … a princeling of the second Gilded Age. Despite Jared’s mediocre academic record, he was admitted to Harvard after his father, Charles, pledged a $2.5 million donation to the university. Father helped son with $10 million in loans for a start in the family business, then Jared continued his elite education at the law and business schools of NYU, where his father had contributed $3 million. Jared repaid his father’s support with fierce loyalty when Charles was sentenced to two years in federal prison in 2005 …

… Kushner failed as a skyscraper owner and a newspaper publisher, but … when his father-in-law became president, Kushner quickly gained power in an administration that raised amateurism, nepotism, and corruption to governing principles … since he became an influential adviser to Trump on the coronavirus pandemic, the result has been mass death.

To watch this pale, slim-suited dilettante breeze into the middle of a deadly crisis, dispensing business-school jargon to cloud the massive failure of his father-in-law’s administration, is to see the collapse of a whole approach to governing. It turns out that scientific experts and other civil servants are not traitorous members of a “deep state”—they’re essential workers, and marginalizing them in favor of ideologues and sycophants is a threat to the nation’s health … It turns out that everything has a cost, and years of attacking government, squeezing it dry and draining its morale, inflict a heavy cost that the public has to pay in lives. All the programs defunded, stockpiles depleted, and plans scrapped meant that we had become a second-rate nation …

Nonetheless, putting an end to the Trump regime is only the beginning of the fight to recover the health of our country.

We can learn from these dreadful days that stupidity and injustice are lethal; that, in a democracy, being a citizen is essential work; that the alternative to solidarity is death. After we’ve come out of hiding and taken off our masks, we should not forget what it was like to be alone.

GEORGE PACKER is a staff writer at The Atlantic. He is the author of Our Man: Richard Holbrooke and the End of the American Century and The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New America.

April 21, 2020

Review of David Wood’s “Transcending Politics: A Technoprogressive Roadmap to a Comprehensively Better Future”

[image error][image error]

I had the pleasure of pre-publication access to David Wood’s recent book Transcending Politics: A Technoprogressive Roadmap to a Comprehensively Better Future. Wood is chair of London Futurists and on the Humanity+ board of directors. Here is my blurb on the book’s back cover:

“Politics plays a significant role in the possibility of our future survival and flourishing. But politics today is largely broken. In response, Wood urges us to embrace transhumanism—to use technology to overcome the limitations of brains formed in the Pleistocene. For without greater intelligence, emotional well-being, and better political institutions, we are doomed. This carefully and conscientiously crafted work defends this thesis with vigor, and it is a welcome relief from the ubiquitous nonsense that passes for political dialogue today. Let us hope that it informs that dialogue and fuels action.” John Messerly, Author of ‘Reason and Meaning’, one of the ‘Top 100 Philosophy Blogs on the Planet’

Now for a few brief thoughts about the book.

Let’s begin with the very first sentence, “There’s no escape: the journey to a healthier society inevitably involves politics.” How then do we solve our political crisis? Wood answers:

In response to our current conceptual crisis, I offer transhumanism. Just as I believe that the journey to a healthier society inevitably involves politics, I also believe that the journey inevitably involves transhumanism.

As Wood puts it, the main theme of the book is expressed as follows:

A better politics awaits us, beckoning us forward. It’s up to us – all of us – whether we recognise that call and take the required actions. Key to these actions will be to harness technology more wisely and more profoundly than before…

Wood’s political orientation is techno-progressive. Techno-progressives argue that technological developments can be empowering and emancipatory when they are regulated by legitimate democratic and accountable authorities to ensure that their costs, risks, and benefits, are all fairly shared by the stakeholders to those developments.[1]

Here is how Wikipedia puts it:

Techno-progressivism maintains that accounts of progress should focus on scientific and technical dimensions, as well as ethical and social ones. For most techno-progressive perspectives the growth of scientific knowledge or the accumulation of technological powers will not represent the achievement of proper progress unless and until it is accompanied by a just distribution of the costs, risks, and benefits of these new knowledges and capacities. At the same time, for most techno-progressive the achievement of better democracy, greater fairness, less violence, and a wider culture of human rights are all desirable, but inadequate in themselves to confront the quandaries of contemporary technological societies unless and until they are accompanied by progress in science and technology to support and implement these values.[2]

To better understand the connection between politics and transhumanism consider what Wood calls the 4 “supers” of techno-progressive transhumanism:

1) Super longevity – overcoming human tendencies toward physical and mental decay and decrepitude

2) Super intelligence – overcoming human tendencies toward mental blind spots and collective stupidity

3) Super wellbeing – overcoming human tendencies toward depression, alienation, vicious emotions, and needless suffering

4) Super democracy – overcoming human tendencies toward tribalism, divisiveness, deception, and the abuse of power

Here I would add “super morality,” although it is somewhat covered under super democracy and super well-being. What I have in mind is “overcoming human tendencies towards selfishness, violence, conflict, and the lack of sympathy and empathy.”

Finally, let’s go back to the opening lines of Aristotle’s Politics,

Every state is a community of some kind, and every community is established with a view to some good; for mankind always act in order to obtain that which they think good. But, if all communities aim at some good, the state or political community, which is the highest of all, and which embraces all the rest, aims at good in a greater degree than any other, and at the highest good.

Here Aristotle argues for the supreme importance of politics. Updating this insight Woods recognizes that we can’t live good lives without good government, and we can’t have good government without transforming human beings.

Needless to say, I enjoyed reading the book, especially since Wood’s views are so consonant with mine! We’ll never transform politics unless we transform ourselves.

*Note – Wood has recently produced an engineering greater human resilience. It doesn’t align perfectly with his 4 “supers” above but there are overlaps. Still an emphasis on overcoming biological, intellectual, psychological, social and moral limitations.

April 16, 2020

Is It Moral to Work for a Tech Giant?

I recently read “The Great Google Revolt” in the New York Times Magazine. The article chronicles the conflict between Google and some of its employees over company practices that some employees deem unethical. I found the article interesting because I taught computer ethics for many years and I’ve always wanted to do meaningful work. Moreover, some of my former students who work at one of the tech giants—Apple, Google, Amazon, Facebook, Microsoft—have asked me about ethical issues in the workplace.

Now tech giants undoubtedly do things that aren’t in the public interest. One only needs to think about how Facebook allows the blatant dissemination of falsehoods in political material, a policy that subverts the integrity of the electoral process and undermines social stability. Other corporations are just as sinister. Oil companies fund climate change denial, a practice that increases the chance of future catastrophic climate change that threatens the species’ survival; and tobacco companies systematically suppressed evidence of the lethality of their products for decades, leading to millions of deaths.

But if you have a job at one of the tech companies and you have moral qualms about how your company’s technology is used, then your choices include:

ignore your moral reservations and use the money (power) your job provides to help yourself and others, influence the political system, etc.

change the company from within if that’s feasible;

find a company whose values more align with your own;

move to a less corrupt country than the USA (because otherwise, your taxes will support some things that don’t align with your values no matter who you work for);

become a slacker if you have enough money and avoid working altogether;

live “off the grid” so as to be less complicit in governmental corruption.

No doubt my readers can imagine other options.

One problem is that some of these solutions may be impractical. Moreover, you live in a world where money is power which can then be used either for good (Bill Gates, Warren Buffett) or ill (Charles Koch, Sheldon Adelson, Donald Trump). So leaving your job might decrease your ability to do good. Furthermore, it is nearly impossible to avoid the global social-economic-political system altogether. In addition, if we push our concerns to their logical limit, simply living and consuming resources may result in a kind of existential guilt. Afterall what we necessarily consume—food, clothing, shelter—is unavailable to others.

I suppose the philosophical problem is, to put it simply, how to do good in a world with so much bad in it. Unfortunately, I don’t think there is any way to live which isn’t complicit somewhat in evil. In answer to all these issues, let me quote from my essay, “Should You Do What You Love?”

So what practical counsel do we give people, in our current time and place, regarding work? Unfortunately, my advice is dull and unremarkable, like so much of the available work. For now, the best recommendation is something like: do the least objectionable/most satisfying work available given your options. That we can’t say more reveals the gap between the real and the ideal, which is itself symptomatic of a flawed society. Perhaps working to change the world so that people can engage in satisfying work is the most meaningful work of all.

And, assuming you find work that isn’t too objectionable and somewhat satisfying, what is the point of doing that work? Here’s what I wrote in my essay “Fulfilling Work.”

In the end, we are small creatures in a big universe. We can’t change the whole world but we can influence it through our interaction with those closest to us, finding joy in the process. We may not change the world by administering to the sick as doctors or nurses or psychologists, or by installing someone’s dishwasher, cleaning their teeth or keeping their internet running. We may not even change it by caring lovingly for our children. But the recipients of such labors may find your work significant indeed. For they received medical care, had someone to talk to, got their teeth cleaned, found an old friend on the internet, avoided the laundromat, or grew up to be the kind of functioning adult this world so desperately needs because of that loving parental care. These may be small things, but if they are not important, nothing is.

Perhaps then it is the sum total of our labors that makes us large. Our labors are not always sexy, but they are necessary to bring about a better future. All those mothers who cared for children and fathers who worked to support them, all those plumbers and doctors and nurses and teachers and firefighters doing their little part in the cosmic dance. All of them recognizing what Victor Frankl taught, that productive work is a constitutive element of a meaningful life.

_________________________________________________________________________

Previous Articles About Work Include:

“Should You Do What You Love?”

“Autonomy, Mastery, and Purpose: What We Really Want From Our Work”

“Friendship is Another Reason to Work”

“The Problem of Work-Life Balance”

April 13, 2020

“Schooling And The Emergence Of Free-Market Authoritarianism: The Struggle For Democratic Life”

(This essay, first appeared at 3 Quarks Daily. Reprinted with permission.)

(This essay, first appeared at 3 Quarks Daily. Reprinted with permission.)

by Eric Weiner

What is commonsense to most people who received a K-12 public education in the United States is that every formal system of state schooling throughout the modern world is designed to educate its students to develop, what Charles Lemert calls “sociologically competencies” within whatever ideological system is dominating at the time of their schooling.

People correctly assume that children going to school during the Weimar Republic, for example, were educated to function competently within that ideological system. Children who were in school during the reign of Chairman Mao in the People’s Republic of China were educated to function competently within that system. Children in China today are educated to be sociologically competent in China’s current government and economic system. Children in France, Spain, Portugal, Israel, Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, and Iran likewise are educated to function competently in those systems. In the Soviet Union, children were educated to function within its version of communism. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, children were required to learn different civic knowledge and skills in order to be competent within the newly emerging political ideologies of reformed nation states.

For people educated in the United States, the connection to ideology and schooling is obvious except when it comes to their own perception of the kind of public schooling they and/or their children received. At most, people might blame the educational system for being too liberal or too conservative, but to recognize the constitutive connection between schooling and ideology goes too far. Ideology is something that defines other governmental and educational systems, not their own.

Ironically, this points to the deep level of ideological indoctrination that state schools have helped to achieve over several generations in the United States. Fueled by the complimentary discourses of choice, individualism, and Judeo-Christian morality, the connection between ideology and schooling is hidden in plain sight behind a translucent veil of American exceptionalism. What we are left with is an education system that teaches students to believe in an illusion of freedom, while disciplining what Michel Foucault famously called docile bodies and obedient minds.

This is not to say that there are not examples of schools, teachers and students that aren’t resisting these ideological forces of schooling. I will address those in another essay. But suffice it to say for now that however determined and important the work of resistance is, it operates more tactically than strategically, making its ideological impact negligible.

For at least the past fifty years, public schools in the United States have been preparing their students to function competently, yet blindly within a “free-market” ideology and a governmental system most accurately described as a neoliberal plutocracy. In spite of the constant attacks from the left and right about public education’s supposed failures, in Althusserian terms it is an incredibly efficient and effective “ideological state apparatus,” refined over the years in large part by educational psychologists, linguists, sociologists, and political scientists to produce a uniquely American subject, one that is unaware of its own civic ignorance and democratic incompetencies, yet is ubernationalistic, overly confident in its cognitive abilities, and morally superior.

Aside from some basic understanding of the role of “choice” as it relates to suffrage, the level of civic knowledge and skills that the average child is taught in public school is almost nonexistent. As a partial consequence of our public-school system’s success, we might now be witnessing the last gasps of our neoliberal plutocracy, while the emergence of “free-market” authoritarianism takes root.

These are remarkable times and whether you look upon this transformation in horror, excitement, caution, or boredom, our public schools, having long-ago abandoned the Jeffersonian mandate to educate young people to appreciate and participate in liberal democracy, have played an important role in preparing students over the last several decades to function competently within this emerging ideological formation.

This is not to say that curriculum developers, teacher-educators, school administrators, and pedagogical practitioners as well as those professionals mentioned in the last paragraph set out to undermine or eradicate neoliberal plutocracy or could foresee what is now emerging in the United States. In preparing students to be sociological competent in a neoliberal plutocracy they were unintentionally helping to lay the groundwork for the emergence of an even less democratic system. Schools don’t create ideological systems and are not the cause of their collapse; they are reactive state apparatuses. Yet they are powerful enough in cooperation with other cultural and political apparatuses to help create the conditions for the emergence of something new as they are, at the same time, working to reproduce the status quo. We might call the unintentional outcomes of this process the “collateral effect” of schooling.

Public schools were designed to ensure that a specific ideology takes root at a hegemonic level and flourishes over time. The fundamental role of public schools has consistently been to socialize young people to function competently in whatever ideological formation was dominating at the time of their schooling.

One notable exception to this can be seen in Thomas Jefferson’s aspirational goal for public schools; only through a system of public education could liberal democracy come to replace the existing plutocracy of which he was an active member. He argued that schools had to be designed with an eye to the future, the goal being to prepare young people to function competently in an ideological system not yet fully established yet sufficiently imagined. Jefferson understood that if a liberal democratic governing structure was to replace, at a hegemonic level, the existing white-supremacist, patriarchal plutocracy, a public system of schooling would have to be designed to prepare future generations with the civic knowledge and skills demanded by the ideology of liberal democracy. Our education system’s connection to ideology, from this historical perspective, is uncontroversial.

More controversial and particular to states with free-market economies and democratic systems of government is how states can prepare citizens for democracy while also educating them to function competently within the ideology of free-market capitalism. States that have no commitment or a “weak” commitment to “freedom,” liberty, and “rights,” have a much easier time doing this honestly and without too many contradictions. The Unites States of America, however, runs into trouble because there are some fundamental contradictions between the ideological demands of neoliberalism and the ideological needs of democracy. There are shared needs between the two ideologies, but they are less formative than the contradictions and less pronounced when seen from the vantage point of class interests.

It may have been Alfie Kohn who said that equity is a pre-condition of a functioning democracy, not its outcome. Capitalism has no such requirement and indeed, at an ideological level, demands inequality as a measure of its success; inequality is a precondition of capitalism as well as a measure of its health. An ideological education in free-market plutocracies, for everyone but the elite, demands no skills or knowledge in critical thinking, rhetoric, literature, philosophy, history or frankly any other academic discipline. Basic facility with reading and maths in combination with job training is really all this ideological formation requires of its citizens.

Obedience more than any other behavior is what is desired, taught, and rewarded. Functioning democracies demand the opposite from their citizens. As such, schools in the United States as well as in other free-market plutocratic ideologies “hide” their ideological agenda behind “official” curricular representations of freedom, liberty and rights. Public schools effectively and efficiently have managed to educate a citizenry unprepared to self-govern, but more than ready to follow state mandates, consume voraciously, and celebrate “negative freedom” (i.e., freedom from) as the ultimate expression of liberty.

Because the evolution of ideology happens over long periods of time, it is almost imperceptible to those being schooled in its norms and rules. Unless people are educated to see the specific ways in which their own ideological systems work, then it is likely they will be able to recognize ideological bias in other systems but remain blind to their own. There is no contradiction here; it’s how ideology and hegemony work. But this does not mean there was/is no push back against this kind of ideological education. There were (and still are) plenty of people who warned of what could happen if schools systematically abdicated their responsibility to educate young people to appreciate democracy and to function as democratic citizens, while, at the same time, schooling them to believe that neoliberalism is the same thing as democracy.

Over the past several decades, the people who run our schools have willfully ignored Jefferson’s warnings that without an educated citizenry a “natural aristocracy” would undermine the liberal democratic ideology of which he aspired to develop. They have been equally as dismissive of John Dewey’s prescient warning that if schools don’t teach young people how to be democratically competent they will be susceptible to the promises made by the demagogues of other ideological systems of governance. Noam Chomsky, also dismissed out-of-hand, has been discussing the “mis-education” of our young people and its implications for our democracy in light of the Trilateral Commission’s report on the indoctrinating role of schools since the mid-1970s. Ivan Illich’s ideas about the need to “de-school” our minds and bodies so that we can live democratically has had little impact on the design, content, and pedagogical focus of public education. Paulo Freire’s work is categorically dismissed as unsuitable and irrelevant to an American context as is the de-colonial work of Franz Fanon and Aimé Césaire. Michael Apple, Jean Anyon, Henry Giroux, and Stanley Aronowitz, among many other “critical” educators, have written hundreds of books and articles about the “hidden curriculum” in our public schools.

To reiterate, the hidden curriculum refers to those ideas, practices and values that students learn in U.S. public schools, beyond the scope of the “official” curriculum, that provides them the skills and knowledge they need to function competently within autocratic neoliberal formations. Stanley Aronowitz goes as far as to say that in the 21st century the “hidden curriculum” isn’t so hidden anymore. Even Diane Ravitch, the once influential neo-conservative architect of anti-democratic school design, has become a vocal critic of public education’s authoritarian tendencies.

Although the emergence of free-market authoritarianism was never over-determined, the writing, at least for these intellectuals, was on the wall. These educational and political thinkers, through a critical analysis of democratic principles and schooling understood the fundamental and somewhat obvious implication of not educating citizens to appreciate democracy and function as democratic citizens; without civic knowledge and skills the democratic experiment would eventually wither and die and be replaced by something else. No one has a crystal ball in which they could see the outcome of this kind of ideological education. Social engineering is a historically sloppy science. And because there are always people struggling to teach against the grain of the hidden curriculum, teacher-centered pedagogies, and instrumental literacies, the emergence of free-market authoritarianism from the evolving neoliberal plutocracy was never over-determined.

Indeed, even at this writing it remains to be seen as to whether this emerging new governmental structure will continue to grow and solidify or whether proponents of democracy (or some other ideology) will be able to do anything to derail its rise to power. But you don’t need a Ph.D. to understand what happens when schools stop educating people about the benefits of democracy and how to live democratically. If young people are schooled to think about education as, first and foremost, a means to a job, then that is what they will think. If they are not taught to appreciate democracy and act democratically then they won’t. If they are not taught how to work across their differences to solve common problems, they will look to a leader that promises to fix all their problems.

Anecdotally, when I ask my undergraduate students why they chose to go to college, they unanimously say it’s about getting a good job. When asked about their understanding about democracy generally and their civic knowledge and skills specifically, they know almost nothing. When asked about “global citizenship,” they typically know even less. When asked if they had to learn these things in elementary, middle or high school, they overwhelmingly say no. If they did learn some basic ideas about these things, they certainly didn’t learn them in a way that makes them competent actors in a democratic system of self-governance. Once we go over the many skills and types of knowledge a person must have to responsibly participate in democratic life, they acknowledge they don’t know the information and don’t have the skills that a functioning democracy requires of its citizens.

Many of them, reasonably then, don’t participate in democratic activities if/when they are available. More troubling perhaps is their docility in the face of authoritarian expressions of power. Most of these students are “good,” meaning they do what they are told. Unless hiding behind a veil of anonymity, they don’t typically challenge, disrupt, disagree, interrogate, critique, or engage across differences of opinion and experience, even when they are in an environment that encourages this kind of behavior. But they all know how to consume and they all want to be trained to get a “good” job after they graduate.

This is the outcome of the kind of ideological schooling many of our young people have gotten over the last several decades with regards to our current neoliberal plutocracy and it has been incredibly successful. Everyday in public schools across the United States students and teachers acquire and learn the knowledge and skills they will need to be considered competent in a free-market plutocracy. Some of the lessons are explicit, while others are embedded in the hidden curriculum. Some of the skills and knowledge is learned because of what is actually taught, while other skills and knowledge is acquired because of what is not taught. Whether the knowledge and skills translate into some kind of measurable success (happiness, wealth, power, prestige, etc.) will depend a lot on where the student’s family is on the index of social and cultural capital.

But regardless, when in school, choice is constrained, as it always is, by economic, social and cultural capital. Power is hierarchal and intimately tied to knowledge and literacy. Discipline is unleashed through structures of reward and punishment. Inequality is naturalized. Opportunity indexes freedom which references “choice.” Individualism normalizes atomization. Docility and obedience equates with good behavior while disruptions are “criminalized” or “pathologized.” Speech is constrained and managed by rules and regulations that serve the status quo. Morality and country intersect in a form of currency. The medium, as Marshall McLuhan foresaw, is the message.

In this transitional moment, what is arising will remain unforeseen until it is more established in some structural way. Yet we must continue to think critically and speculatively using the best intellectual resources we have to anticipate what system is emerging from our free-market plutocracy. We can and should also continue to struggle and organize against any emerging system that appears to be taking the form of authoritarianism even if we are not certain as to the final form it will take.

But we can’t simply be fighting against these emerging systems; we must also be as diligent in fighting for alternatives. Whether the fight is for liberal, direct, radical, or some other form of a self-governing system, we should be prepared to articulate a defense of this ideology and have a plan for how to educate people to function competently and critically within it. Whether or not free-market authoritarianism or some other autocratic system of governance establishes itself in the United States, I believe we can and should reassert the value of a democratic education in preparing young people to both appreciate democracy and learn the skills that will allow them to function democratically.

A democratic education prepares young people to recognize and resist demagoguery when confronted by it. It supports their intellectual and emotional development with regards to diversity and difference. It prepares them to interrogate ideological formations, their own and others. It teaches them civic skills and knowledge so that they not only can participate but are compelled to participate in their communities. It teaches dialogue, debate, rhetoric, argument, critical thought, creative problem-solving, organizing, strategies of resistance, empathy/compassion, and compromise.

Democracies require a citizenry educated in literature, philosophy, theology, geography, media, rhetoric, critical/creative thinking, and history. Democracy is not a zero-sum game therefore students should learn that “winners” don’t take all, but have a responsibility to make sure the “losers” still get some of what they want or need. Democracy requires a level of intellectual maturity and emotional intelligence. A democratic education teaches young people to care for each other, to see themselves in each other. It can be loud, angry, frustrating, and intimidating, but it also demands mutual respect and a commitment to non-violence. Democratic education begins by structuring our schools in a way that requires students and teachers to think and act democratically. It’s not so much about teaching about democracy (although that’s part of it), but having daily and substantive democratic experiences. This is Dewey’s major contribution to our understanding of democratic education; we learn how to live in a democracy by living democratically. If a free-market authoritarian system does finally take root, we can thank our system of public schooling for helping to prepare our young people to reflexively act and think in accordance with its ideological assumptions and demands.

Schooling And “The Emergence Of Free-Market Authoritarianism: The Struggle For Democratic Life”

(This essay, first appeared at 3 Quarks Daily. Reprinted with permission.)

(This essay, first appeared at 3 Quarks Daily. Reprinted with permission.)

by Eric Weiner

What is commonsense to most people who received a K-12 public education in the United States is that every formal system of state schooling throughout the modern world is designed to educate its students to develop, what Charles Lemert calls “sociologically competencies” within whatever ideological system is dominating at the time of their schooling.

People correctly assume that children going to school during the Weimar Republic, for example, were educated to function competently within that ideological system. Children who were in school during the reign of Chairman Mao in the People’s Republic of China were educated to function competently within that system. Children in China today are educated to be sociologically competent in China’s current government and economic system. Children in France, Spain, Portugal, Israel, Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, and Iran likewise are educated to function competently in those systems. In the Soviet Union, children were educated to function within its version of communism. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, children were required to learn different civic knowledge and skills in order to be competent within the newly emerging political ideologies of reformed nation states.

For people educated in the United States, the connection to ideology and schooling is obvious except when it comes to their own perception of the kind of public schooling they and/or their children received. At most, people might blame the educational system for being too liberal or too conservative, but to recognize the constitutive connection between schooling and ideology goes too far. Ideology is something that defines other governmental and educational systems, not their own.

Ironically, this points to the deep level of ideological indoctrination that state schools have helped to achieve over several generations in the United States. Fueled by the complimentary discourses of choice, individualism, and Judeo-Christian morality, the connection between ideology and schooling is hidden in plain sight behind a translucent veil of American exceptionalism. What we are left with is an education system that teaches students to believe in an illusion of freedom, while disciplining what Michel Foucault famously called docile bodies and obedient minds.

This is not to say that there are not examples of schools, teachers and students that aren’t resisting these ideological forces of schooling. I will address those in another essay. But suffice it to say for now that however determined and important the work of resistance is, it operates more tactically than strategically, making its ideological impact negligible.

For at least the past fifty years, public schools in the United States have been preparing their students to function competently, yet blindly within a “free-market” ideology and a governmental system most accurately described as a neoliberal plutocracy. In spite of the constant attacks from the left and right about public education’s supposed failures, in Althusserian terms it is an incredibly efficient and effective “ideological state apparatus,” refined over the years in large part by educational psychologists, linguists, sociologists, and political scientists to produce a uniquely American subject, one that is unaware of its own civic ignorance and democratic incompetencies, yet is ubernationalistic, overly confident in its cognitive abilities, and morally superior.

Aside from some basic understanding of the role of “choice” as it relates to suffrage, the level of civic knowledge and skills that the average child is taught in public school is almost nonexistent. As a partial consequence of our public-school system’s success, we might now be witnessing the last gasps of our neoliberal plutocracy, while the emergence of “free-market” authoritarianism takes root.

These are remarkable times and whether you look upon this transformation in horror, excitement, caution, or boredom, our public schools, having long-ago abandoned the Jeffersonian mandate to educate young people to appreciate and participate in liberal democracy, have played an important role in preparing students over the last several decades to function competently within this emerging ideological formation.

This is not to say that curriculum developers, teacher-educators, school administrators, and pedagogical practitioners as well as those professionals mentioned in the last paragraph set out to undermine or eradicate neoliberal plutocracy or could foresee what is now emerging in the United States. In preparing students to be sociological competent in a neoliberal plutocracy they were unintentionally helping to lay the groundwork for the emergence of an even less democratic system. Schools don’t create ideological systems and are not the cause of their collapse; they are reactive state apparatuses. Yet they are powerful enough in cooperation with other cultural and political apparatuses to help create the conditions for the emergence of something new as they are, at the same time, working to reproduce the status quo. We might call the unintentional outcomes of this process the “collateral effect” of schooling.

Public schools were designed to ensure that a specific ideology takes root at a hegemonic level and flourishes over time. The fundamental role of public schools has consistently been to socialize young people to function competently in whatever ideological formation was dominating at the time of their schooling.

One notable exception to this can be seen in Thomas Jefferson’s aspirational goal for public schools; only through a system of public education could liberal democracy come to replace the existing plutocracy of which he was an active member. He argued that schools had to be designed with an eye to the future, the goal being to prepare young people to function competently in an ideological system not yet fully established yet sufficiently imagined. Jefferson understood that if a liberal democratic governing structure was to replace, at a hegemonic level, the existing white-supremacist, patriarchal plutocracy, a public system of schooling would have to be designed to prepare future generations with the civic knowledge and skills demanded by the ideology of liberal democracy. Our education system’s connection to ideology, from this historical perspective, is uncontroversial.

More controversial and particular to states with free-market economies and democratic systems of government is how states can prepare citizens for democracy while also educating them to function competently within the ideology of free-market capitalism. States that have no commitment or a “weak” commitment to “freedom,” liberty, and “rights,” have a much easier time doing this honestly and without too many contradictions. The Unites States of America, however, runs into trouble because there are some fundamental contradictions between the ideological demands of neoliberalism and the ideological needs of democracy. There are shared needs between the two ideologies, but they are less formative than the contradictions and less pronounced when seen from the vantage point of class interests.

It may have been Alfie Kohn who said that equity is a pre-condition of a functioning democracy, not its outcome. Capitalism has no such requirement and indeed, at an ideological level, demands inequality as a measure of its success; inequality is a precondition of capitalism as well as a measure of its health. An ideological education in free-market plutocracies, for everyone but the elite, demands no skills or knowledge in critical thinking, rhetoric, literature, philosophy, history or frankly any other academic discipline. Basic facility with reading and maths in combination with job training is really all this ideological formation requires of its citizens.

Obedience more than any other behavior is what is desired, taught, and rewarded. Functioning democracies demand the opposite from their citizens. As such, schools in the United States as well as in other free-market plutocratic ideologies “hide” their ideological agenda behind “official” curricular representations of freedom, liberty and rights. Public schools effectively and efficiently have managed to educate a citizenry unprepared to self-govern, but more than ready to follow state mandates, consume voraciously, and celebrate “negative freedom” (i.e., freedom from) as the ultimate expression of liberty.

Because the evolution of ideology happens over long periods of time, it is almost imperceptible to those being schooled in its norms and rules. Unless people are educated to see the specific ways in which their own ideological systems work, then it is likely they will be able to recognize ideological bias in other systems but remain blind to their own. There is no contradiction here; it’s how ideology and hegemony work. But this does not mean there was/is no push back against this kind of ideological education. There were (and still are) plenty of people who warned of what could happen if schools systematically abdicated their responsibility to educate young people to appreciate democracy and to function as democratic citizens, while, at the same time, schooling them to believe that neoliberalism is the same thing as democracy.

Over the past several decades, the people who run our schools have willfully ignored Jefferson’s warnings that without an educated citizenry a “natural aristocracy” would undermine the liberal democratic ideology of which he aspired to develop. They have been equally as dismissive of John Dewey’s prescient warning that if schools don’t teach young people how to be democratically competent they will be susceptible to the promises made by the demagogues of other ideological systems of governance. Noam Chomsky, also dismissed out-of-hand, has been discussing the “mis-education” of our young people and its implications for our democracy in light of the Trilateral Commission’s report on the indoctrinating role of schools since the mid-1970s. Ivan Illich’s ideas about the need to “de-school” our minds and bodies so that we can live democratically has had little impact on the design, content, and pedagogical focus of public education. Paulo Freire’s work is categorically dismissed as unsuitable and irrelevant to an American context as is the de-colonial work of Franz Fanon and Aimé Césaire. Michael Apple, Jean Anyon, Henry Giroux, and Stanley Aronowitz, among many other “critical” educators, have written hundreds of books and articles about the “hidden curriculum” in our public schools.

To reiterate, the hidden curriculum refers to those ideas, practices and values that students learn in U.S. public schools, beyond the scope of the “official” curriculum, that provides them the skills and knowledge they need to function competently within autocratic neoliberal formations. Stanley Aronowitz goes as far as to say that in the 21st century the “hidden curriculum” isn’t so hidden anymore. Even Diane Ravitch, the once influential neo-conservative architect of anti-democratic school design, has become a vocal critic of public education’s authoritarian tendencies.

Although the emergence of free-market authoritarianism was never over-determined, the writing, at least for these intellectuals, was on the wall. These educational and political thinkers, through a critical analysis of democratic principles and schooling understood the fundamental and somewhat obvious implication of not educating citizens to appreciate democracy and function as democratic citizens; without civic knowledge and skills the democratic experiment would eventually wither and die and be replaced by something else. No one has a crystal ball in which they could see the outcome of this kind of ideological education. Social engineering is a historically sloppy science. And because there are always people struggling to teach against the grain of the hidden curriculum, teacher-centered pedagogies, and instrumental literacies, the emergence of free-market authoritarianism from the evolving neoliberal plutocracy was never over-determined.

Indeed, even at this writing it remains to be seen as to whether this emerging new governmental structure will continue to grow and solidify or whether proponents of democracy (or some other ideology) will be able to do anything to derail its rise to power. But you don’t need a Ph.D. to understand what happens when schools stop educating people about the benefits of democracy and how to live democratically. If young people are schooled to think about education as, first and foremost, a means to a job, then that is what they will think. If they are not taught to appreciate democracy and act democratically then they won’t. If they are not taught how to work across their differences to solve common problems, they will look to a leader that promises to fix all their problems.

Anecdotally, when I ask my undergraduate students why they chose to go to college, they unanimously say it’s about getting a good job. When asked about their understanding about democracy generally and their civic knowledge and skills specifically, they know almost nothing. When asked about “global citizenship,” they typically know even less. When asked if they had to learn these things in elementary, middle or high school, they overwhelmingly say no. If they did learn some basic ideas about these things, they certainly didn’t learn them in a way that makes them competent actors in a democratic system of self-governance. Once we go over the many skills and types of knowledge a person must have to responsibly participate in democratic life, they acknowledge they don’t know the information and don’t have the skills that a functioning democracy requires of its citizens.

Many of them, reasonably then, don’t participate in democratic activities if/when they are available. More troubling perhaps is their docility in the face of authoritarian expressions of power. Most of these students are “good,” meaning they do what they are told. Unless hiding behind a veil of anonymity, they don’t typically challenge, disrupt, disagree, interrogate, critique, or engage across differences of opinion and experience, even when they are in an environment that encourages this kind of behavior. But they all know how to consume and they all want to be trained to get a “good” job after they graduate.

This is the outcome of the kind of ideological schooling many of our young people have gotten over the last several decades with regards to our current neoliberal plutocracy and it has been incredibly successful. Everyday in public schools across the United States students and teachers acquire and learn the knowledge and skills they will need to be considered competent in a free-market plutocracy. Some of the lessons are explicit, while others are embedded in the hidden curriculum. Some of the skills and knowledge is learned because of what is actually taught, while other skills and knowledge is acquired because of what is not taught. Whether the knowledge and skills translate into some kind of measurable success (happiness, wealth, power, prestige, etc.) will depend a lot on where the student’s family is on the index of social and cultural capital.

But regardless, when in school, choice is constrained, as it always is, by economic, social and cultural capital. Power is hierarchal and intimately tied to knowledge and literacy. Discipline is unleashed through structures of reward and punishment. Inequality is naturalized. Opportunity indexes freedom which references “choice.” Individualism normalizes atomization. Docility and obedience equates with good behavior while disruptions are “criminalized” or “pathologized.” Speech is constrained and managed by rules and regulations that serve the status quo. Morality and country intersect in a form of currency. The medium, as Marshall McLuhan foresaw, is the message.

In this transitional moment, what is arising will remain unforeseen until it is more established in some structural way. Yet we must continue to think critically and speculatively using the best intellectual resources we have to anticipate what system is emerging from our free-market plutocracy. We can and should also continue to struggle and organize against any emerging system that appears to be taking the form of authoritarianism even if we are not certain as to the final form it will take.

But we can’t simply be fighting against these emerging systems; we must also be as diligent in fighting for alternatives. Whether the fight is for liberal, direct, radical, or some other form of a self-governing system, we should be prepared to articulate a defense of this ideology and have a plan for how to educate people to function competently and critically within it. Whether or not free-market authoritarianism or some other autocratic system of governance establishes itself in the United States, I believe we can and should reassert the value of a democratic education in preparing young people to both appreciate democracy and learn the skills that will allow them to function democratically.

A democratic education prepares young people to recognize and resist demagoguery when confronted by it. It supports their intellectual and emotional development with regards to diversity and difference. It prepares them to interrogate ideological formations, their own and others. It teaches them civic skills and knowledge so that they not only can participate but are compelled to participate in their communities. It teaches dialogue, debate, rhetoric, argument, critical thought, creative problem-solving, organizing, strategies of resistance, empathy/compassion, and compromise.

Democracies require a citizenry educated in literature, philosophy, theology, geography, media, rhetoric, critical/creative thinking, and history. Democracy is not a zero-sum game therefore students should learn that “winners” don’t take all, but have a responsibility to make sure the “losers” still get some of what they want or need. Democracy requires a level of intellectual maturity and emotional intelligence. A democratic education teaches young people to care for each other, to see themselves in each other. It can be loud, angry, frustrating, and intimidating, but it also demands mutual respect and a commitment to non-violence. Democratic education begins by structuring our schools in a way that requires students and teachers to think and act democratically. It’s not so much about teaching about democracy (although that’s part of it), but having daily and substantive democratic experiences. This is Dewey’s major contribution to our understanding of democratic education; we learn how to live in a democracy by living democratically. If a free-market authoritarian system does finally take root, we can thank our system of public schooling for helping to prepare our young people to reflexively act and think in accordance with its ideological assumptions and demands.

April 9, 2020

Summary and Meaning of Camus’ “The Plague”

[image error]Albert Camus (1913 – 1960) was a French author and philosopher who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1957. His novel The Plague[image error] has recently garnered much worldwide attention do to the pandemic of 2020. As a philosopher familiar with Camus’ thought, I’d like to highlight the book’s main philosophical themes. But first a very brief plot summary.

Part 1

In the town of Oran, thousands of rats die. People become hysterical and the authorities respond by killing rats. The main character, the atheist Dr. Bernard Rieux, realizes there is a plague, but the authorities are slow to accept the situation, fighting over how to respond. Eventually, they declare a pandemic. Soon the hospitals are overflowing and many die.

Part 2

The people react differently to the town’s quarantine. Some try to commit suicide or covertly leave town; a priest assumes the plague is divine punishment; a criminal becomes wealthy as a smuggler; and others, like Dr. Rieux, treat patients as best they can.

Part 3

The situation worsens and the authorities shoot people who try to flee. They declare martial law to control violence and looting; conduct funerals without ceremony or concern for the families of the deceased. Gradually, people become despondent, wasting away both emotionally and physically.

Part 4

The plague continues for months and again responses vary. Dr. Rieux controls his emotions in order to continue his work, while others seemingly flourish due to their close connection with strangers. An antiplague serum is developed but it doesn’t save even an innocent child. The priest argues that the child’s suffering is a test of faith—the priest soon dies too.

Part 5

Gradually deaths from the plague start to decline and people begin to celebrate. But many of the main characters have died of the disease. Dr. Rieux’s wife, who was being treated elsewhere for an unrelated illness, also dies. The narrator concludes the novel by stating that there is more to admire than to despise in humans.

Camus’ Philosophy

The key to understanding Camus’ novels is to know that he was an atheist and an existentialist who emphasized the absurd—the conflict between our desire for value and meaning and our inability to find any in a meaningless and irrational universe.

But Camus believed that we should revolt against absurdity—not by cowardly committing suicide or fleeing into religious faith—but by taking responsibility for our lives, enjoying the goodness and beauty around us, and by creating our own meaning in an objectively meaningless world. We do this primarily by struggling against suffering and death even if our efforts fail. This is what the novel’s hero does, fighting defiantly against absurdity.

Philosophical Themes in the Novel

The plague represents this absurdity. There is no justice regarding who lives and dies from the plague; there is no rational or moral meaning to be derived from it; religious myths or angry gods don’t explain it. The gods watch the unfolding calamity with arms folded either unwilling or unable to do anything. The plague is neither rational nor just.

Moreover, wishful thinking doesn’t help, but instead, it distorts reality. Miracle cures won’t work and real cures aren’t right around the corner. Life is fleeting, our lives are ephemeral. Neither wealth nor education completely shield us from microscopic pathogens. Yet people forget all this. They’re surprised that they’re vulnerable, that their status or accomplishments don’t provide immunity. They shouldn’t be surprised.

For the plague is everywhere—people suffer and die; psychopaths create havoc; nations commit genocide. We live in a plague filled world. The plague is always with us—our lives can end at any moment. Death doesn’t await us at the end of the tracks, it’s right here, now. It is a constant companion of our transitory lives. Eventually, the plague will kill us all.

What then should we do? Express care and concern for our fellow travelers and try to help them. That’s what the novel’s hero Dr. Rieux does. He accepts the absurdity of suffering, death, and meaninglessness, but battles them nonetheless. He doesn’t treat his patients for no other reason than that he sympathizes with their undeserved plight.

We all have the plague; we live in it midst; and we don’t deserve it. Nothing makes much sense. Still, all we can do is care for each other.

____________________________________________________________________

Here is a brief summary of Camus’ essay “The Myth of Sisyphus,” the best introduction to his philosophy.

Also, The School of Life produced an excellent, short video about the novel’s philosophical themes. It’s definitely worth a watch.

Summary of Camus’ The Plague

[image error]Albert Camus (1913 – 1960) was a French author and philosopher who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1957. His great novel The Plague[image error] has recently garnered much worldwide attention. As a professional philosopher familiar with Camus’ thought, I’d like to highlight some of the book’s philosophical themes that are relevant to the pandemic of 2020.

But first a very, very brief plot overview …

Part 1

In the town of Oran, thousands of rats die. People become hysterical and the authorities respond by killing rats. The main character, the atheist Dr. Bernard Rieux, realizes there is a plague, but the authorities are slow to accept the situation, fighting over how to respond. Eventually, they declare a pandemic. Soon the hospitals are overflowing and many die.

Part 2

The people react differently to the town’s quarantine. Some try to commit suicide or covertly leave town; a priest assumes the plague is divine punishment; a criminal becomes wealthy as a smuggler; and others, like Dr. Rieux, treat patients as best they can.

Part 3

The situation worsens and the authorities shoot people who try to flee. They declare martial law to control violence and looting; conduct funerals without ceremony or concern for the families of the deceased. Gradually, people become despondent, wasting away both emotionally and physically.

Part 4

The plague continues for months and again responses vary. Dr. Rieux controls his emotions in order to continue his work, while others seemingly flourish due to their close connection with strangers. An antiplague serum is developed but it doesn’t save even an innocent child. The priest argues that the child’s suffering is a test of faith—the priest soon dies too.

Part 5

Gradually deaths from the plague start to decline and the people begin to celebrate. But many of the main characters die of the disease. Dr. Rieux’s wife, who was being treated elsewhere for an unrelated illness, also dies. The narrator concludes the novel by stating that there is more to admire than to despise in humans.

Camus’ Philosophy

The key to understanding Camus’ novels is to know that he was an atheist and an existentialist who emphasized the absurd—the conflict between our desire for value and meaning and our inability to find any in a meaningless and irrational universe in which we all suffer and die.

But Camus believed that we can revolt against absurdity—not by cowardly committing suicide or fleeing into religious faith—but by taking responsibility for our lives, enjoying the beauty around us, and creating our own meaning in an objectively meaningless world. We do this primarily by struggling against suffering and death even if our efforts fail. This is what the novel’s hero does, fighting defiantly against the absurdity.

Philosophical Themes in the Novel

The plague represents this absurdity. There is no justice regarding who lives and dies; there is no rational or moral meaning to be derived; religious myths or angry gods don’t explain it. The gods watch the unfolding calamity with arms folded either unwilling or unable to do anything. The plague is neither rational nor just.

Moreover, wishful thinking doesn’t help either; instead, it distorts reality. Miracle cures won’t work and real cures aren’t right around the corner. Life is fleeting, our lives ephemeral. Neither wealth nor education completely shield us from microscopic pathogens. Yet people forget all this and assume they’re permanent, surprised that they’re vulnerable, and that their status or accomplishments don’t provide immunity.

The novel’s hero and protagonist accepts this absurdity but battles it nonetheless. The plague is always with us. (People die miserably; psychopaths kill children and rule countries; nations commit genocide.) What then do we do? The best we can to rectify the situation knowing that our efforts may well fail. Dr. Rieux has secular faith. He cares about other human beings because he cares about them. (I’m reminded of David Hume who said that morality derives not from reason or gods but from human sympathy.)

The plague is everywhere and it’s always with us—our lives can be taken from us at any moment. Death doesn’t await us at the end of the tracks, it’s right here, now. The plague represents this absurdity of suffering and death. It reminds us that our lives are transitory and fleeting. In response, we should express care and concern for our fellow travelers.

____________________________________________________________________

Here is a brief summary of Camus’ essay “The Myth of Sisyphus,” the best introduction to his philosophy.

Also, The School of Life produced an excellent, short video about the novel’s philosophical themes. It’s definitely worth a watch.

April 6, 2020

Review of Martin Hägglund’s, This Life: Secular Faith and Spiritual Freedom

[image error]

Martin Hägglund’s, This Life: Secular Faith and Spiritual Freedom, is one of the most sublime works I’ve ever read—and I’ve devoured thousands of books in my life. It is a work of great erudition and originality; it is carefully and conscientiously crafted; it overflows with thoughtful insights, poetic passages, and sparkling prose. It is, quite simply, a masterpiece.

Since I cannot do the book justice in a brief review, I’ll focus mostly on the compatibility of Hägglund‘s views about death and meaning with my transhumanism.

The book is divided into two parts. In the first, Hägglund critiques religious ideas of an afterlife as both unattainable and undesirable. Instead, he says, we should find meaning in the fragility and finitude of this life by practicing what he calls secular faith. In part two, he argues that capitalism alienates us from our finite lives while democratic socialism best provides the conditions in which we can use our time to express our spiritual freedom.

Hägglund defines finitude as being dependent on others and living in the shadow of death. Likewise, our projects are finite because they live on only to the extent that someone is committed to them. For me, finitude also includes my physical, psychological, moral, and intellectual limitations. Regarding my projects, I’d add that they can survive us if others carry on our work after our deaths. (Bertrand Russell expressed this idea beautifully.)

Religious immortality might seem to solve the problem of finitude but, according to Hägglund, an eternal afterlife is not only unachievable but undesirable. Why? Because it would be a reality where there would be nothing to be concerned about and nothing could go wrong. Moreover, activities there would be self-sustaining—not requiring any effort on our part. Therefore, activity in a heaven wouldn’t be our own.

Hägglund offers other arguments to undermine the supposed value of immortality: that things only matter to us because we could lose them; that the question of how we live our lives only makes sense if we’re finite; and that we wouldn’t use our time well if it was unlimited. Most importantly, he argues that the unchanging, permanent nature of heaven would render it static and unappealing.

While I agree with Hägglund that a religious afterlife is unattainable and undesirable, I don’t think his arguments apply to secular or scientific immortality—using science and technology to extend good lives as long as possible, perhaps even prolonging them indefinitely. (For more see my “Death Should Be Optional“) My wife would matter to me as much if not more if she were going to live a thousand or a million years; the question “what should I do with my life?” is perfectly intelligible without the constant threat of death; and people waste time or use it wisely independent of how much of it they think they possess.

I also agree that if things were eternally perfect, there would be nothing to do or be concerned about, but in my vision of scientific immortality, we approach perfection like an asymptote in analytic geometry—a line that continually approaches a curve without reaching it. So there is nothing static about my view of an exceptionally long life. (Ed Gibney has suggested another image. Scientific immortality can be compared to approaching a perfect circle by shaving the edges off a polygon forever.)