John G. Messerly's Blog, page 47

June 11, 2020

Review of Overdoing Democracy: Why We Must Put Politics In Its Place

[image error]©John Danaher (Reprinted with Permission)

Aristotle once said that humans are political by their nature. Certainly, political processes and institutions are central to human life. But are they everything? Is everything we do inherently political? And, more importantly, should everything we do be seen to be inherently political?

These are the questions that Robert Talisse takes up in his recent book, Overdoing Democracy. He argues that contemporary life (specifically contemporary life in the US) is overly politicized. Political identities and political causes have seeped into and contaminated virtually every aspect of our lives. As he puts it:

[C]ontemporary democratic societies have embraced a hyperextended conception of democracy’s reach. They have adopted a conception of democracy’s scope that allows for the attribution of political significance — and accountability qua citizen — to too much of what people do, and accordingly tend to recognize too many spaces as sites in which democratic citizenship is to be enacted…we come to see one another solely as political agents who either obstruct or help enable our own political projects. (Talisse 2019, 48)

In other words, we have created a world in which there is no respite from politics. We are forced to see ourselves through our political identities and loyalties and to see others in the same way. Talisse argues that this is a bad thing because over-politicization crowds out the other goods of life, resulting in an impoverished form of existence. He thinks we should push back against this wave of over-politicization and find some space for non-political activity and engagement. He thinks this is particularly necessary in an age of increasing political polarisation.

The book is thought-provoking and well written. The argument against over-politicization builds in a careful and logical way, and there is some interesting argumentation with respect to polarisation and over-politicization in the book. But, as I mentioned to Robert when I recently spoke to him, I may not be the ideal reader for the book since I was already primed to agree with its central thesis. I tend not to think of myself or my actions or my relationships through an overly political lens. It’s not that I am not interested in politics — I pay close attention to political debates and developments around the world — but I try not to define myself through political loyalties or identities. The main reason for this is one of epistemic humility. I don’t have well-formed or well-reasoned views on the vast majority of political issues. I resent the pressure to pick a side.

But this pressure is there. I am often reminded by my academic colleagues that I cannot afford the luxury of sitting on the fence. They tell me that everything is political; that to not pick a side is, in some sense, to favor the political status quo and mark oneself out as a political conservative. And since I don’t like the idea of being labeled a political conservative, I sometimes relent and express loyalty to ideas I am not entirely comfortable with. Am I wrong to do this?

What follows is not going to be a full review of Robert’s book. Instead, I want to critically engage with three key ideas from it, all from the opening sections of the book. First, I want to consider the main argument against over-politicization from the book: the crowding out argument. Second, I want to examine an objection to this argument that claims that you cannot put politics in its place because “everything is politics”. Third, I want to examine the objection that claims that the desire to ‘put politics in its place’ is an expression of political conservatism. Throughout, I will be folding my own reflections and experiences into the discussion. So what follows is, in part, an exercise in philosophical self-analysis. I offer it in the hope that what I say might resonate with (or challenge) other people’s experiences.

1. Overpoliticisation and the Crowding Out Argument

Talisse presents his thesis in a logical and patient way. He builds from simple definitions and concepts to an extended argument against political overreach. He points out that there are a number of activities that are central to democratic politics — for example, voting, participating in deliberative debates, acquiring and disseminating information about political candidates and policies. He also points out that these activities ought to occur in certain places — for example, newsrooms, town halls, political hustings and conferences, and parliamentary chambers. His thesis about over-politicization is simply that the activities that are central to politics now occur in too many places — places where they really ought not to occur. Examples of this overreach would include the politicization of the family dinner table, the office, leisure activities, and so on.

The suggestion from the get-go is that this political overreach is a bad thing, but why is this? Why is it that political activities ought to occur in only a few specific places? Talisse’s main argument for the badness of political overreach is the ‘crowding out’ argument. Very roughly, his claim is that if we allow for political overreach then we allow politics to crowd out the other goods of life. He has a nice analogy that he uses to illustrate this problem.

Imagine Anne. Anne is a fitness freak who spends all her waking hours focused on honing her fitness. She carefully manages what she eats and spends most of her time in the gym. As a result, Anne is very fit and her fitness is clearly a good thing. It gives her a level of health and physical well-being that few people attain. But Anne is such a fitness freak that she has little time for anything else in life. She has no time to dedicate to her family, friends, career, social networks, art, literature, sex and relationships, and so on.

Is Anne living a good life? Obviously there are some goods in her life (her fitness) but she is also missing out on a lot. Her dedication to fitness has crowded out lots of other things that would make her life good. There is something imbalanced and incomplete about what she is doing. Furthermore, there might even be something perverse to it as well. After all, few people think that fitness is an end in itself. We don’t simply want to be fit. We want to be fit in order to be able to enjoy other goods, e.g. playing social sports, and living a longer life that gives us access to other goods. So it’s not just that her fitness obsession crowds out the other goods of life, it also undermines itself.

Talisse’s argument about political overreach follows this basic structure. He claims that an obsession with politics can crowd out the other goods of life. If you spend every waking hour obsessed with political processes, policies, and identities, you never get to enjoy any of the other important things that make up a well-lived life.

Furthermore, politics is not an end in itself. There are some political obsessives who might enjoy nothing more than thinking about political strategy and power every waking hour, but for the majority of people, politics is means to other ends — education, health, employment, family, and so on. If politics dominates our attention, these other goods can get ignored. Of course, it is probably true to say that most people aren’t political obsessives in the sense that they completely ignore everything else that is good, but if political overreach is encouraged, then it becomes more and more difficult to sustain any oasis of life that is free from political concerns.

I am sympathetic to this idea. For what it’s worth, I defended a similar-ish claim in my book Automation and Utopia when I looked at the political effects of technology. I pointed out that one thing technology does is that it redistributes power in society. What’s more, in recent times, it seems to be doing this in a highly inegalitarian way (hence the dominance of certain companies in the market). But I also argued that we shouldn’t focus on the redistribution of power in and of itself. We should focus on how that power gets translated into effects on people’s lives (specifically how it affects the conditions that need to be satisfied in order to live a flourishing and meaningful life). One reason for this is that there is more than likely always going to be some power structure or power elite in society, and so the challenge is to make sure that this power structure supports, rather than undermines, the conditions we need to satisfy to live flourishing lives.

This has turned out to be a controversial claim. Some people have suggested to me that we should care about power structures in and of themselves. I continue to find this confusing. I have an instinctual preference for egalitarian and decentralized power structures, but I don’t think I prefer them for their own sake. I prefer them because I believe they are more likely to have good effects on people’s lives (in most cases). But I could be wrong about this and so there are some cases where I think inegalitarian and centralized power structures make more sense (e.g. I think some industries and utilities work best when they are under monopolistic public control).

People who resist this idea and think that we should care about power structures in and of themselves, seem to me to assume, implicitly, that certain power structures necessarily have bad effects and so should be resisted. They may well be correct in this. But I would respond to them by saying that this doesn’t undermine the claim that what we really care about are the effects these structures have on people’s lives. In other words, the following argument could apply to this debate:

(1) When it comes to evaluating political processes and power structures, what we ultimately care about are the effects they have on the goods of life.

(2) Certain political processes and power structures necessarily have negative effects on the goods of life.

(3) Therefore, we should focus on these specific political processes and power structures.

People like myself and Talisse are concerned primarily with the truth of premise (1); critics who care about power structures might tell us we should focus more on premise (2) and its implications. We might just be talking past each other.

One final caveat about this. What I have just argued is not inconsistent with the view that certain political processes have intrinsic goods associated with them. For example, somebody could argue that public, transparent and deliberative processes are better than their opposites because they allow people to be the active agents of political change and not just the passive recipients of its benefits (or burdens). In fact, I have made precisely that argument in the past when critiquing modes of algorithmic governance. This does not, however, imply that deliberative processes are the only good that we should care about or that deliberative political processes are not primarily valued because of the effects they have on people’s lives.

2. Is Everything Politics?

An obvious objection to Talisse’s argument is that it is impossible to keep politics in its place because, ultimately, everything is politics. In other words, no matter where you are or what you are doing, politics infests and pervades it. It cannot be escaped and kept in its box.

Talisse points out that there are several problems with this objection. First, claims of the sort “everything is X” are usually problematic. If I say “everything is blue”, you have to ask “what about all the other colors?”. If I say “everything is water”, you have to wonder, “but what about all the other things that don’t seem to be anything like water?” If I say “everything is politics”, you have to ask “what about the things that don’t seem overtly political?”

Furthermore, even if it were true that everything was politics, you would still have to consider the fact that not everything is political in the same way so, if everything is political, these things must be political in different ways and for different reasons. So you will have to start introducing concepts and ideas that help you differentiate between different political kinds of things. More generally, if you are making a foundational claim about the nature of everything you better have the resources to explain it and back it up. But once you start explaining it and backing it up, you almost invariably have to rely on concepts and ideas that are not themselves the same as the thing that you claim is at the foundation of everything. So, pretty quickly, it starts to seem as if there are other things in the world.

Talisse doesn’t make much of this counterargument, hiding it away in a footnote. His more important counterargument is that there are two different ways in which to interpret the claim that “everything is politics”.

Necessity Interpretation: Political factors and processes play some necessary and non-negligible role in explaining all aspects of our lives.

Sufficiency Interpretation: Political factors and processes are sufficient to explain all facets of human life.

Talisse argues that the first interpretation is sensible and “surely correct”, but that it doesn’t undermine his thesis because he is not assuming that politics can be eliminated from our lives but, rather, that it can be put in its proper place. I don’t agree with Talisse that this interpretation is surely correct. It strikes me as trivially true that some aspects of our lives are not explained by any political processes or factors. For example, consider the fact that we are bound by the law of gravity or that we breathe oxygen. I don’t think political processes or factors play any role in explaining these aspects of human life.

That said, it seems clear from the context that Talisse intends the claim to have a more limited scope, viz. that political factors play a non-negligible role in explaining virtually all aspects of human behavior and social life. This is surely correct. The fact that I am sitting a desk right now and drinking coffee may not seem, initially, like it is explained by political factors but, when I reflect upon it, there are numerous political factors and processes at play, e.g. rules of property and employment law that give me the right to the desk and reward me for a certain kind of labor, facets of international economics and trade relations that facilitate the arrival of the coffee, and so on.

Talisse argues that the second interpretation is neither true nor significant. It is a stretch to claim that all aspects of human behavior and social life are sufficiently accounted for by political factors. They may play some role in the explanation, but there are surely other factors at play too. I tend to agree with him on this. Consider, once again, the laws of physics and biological evolution. They surely play some non-negligible role in explaining facets of our behavior and social lives. If that’s right, then not everything is reducible to the political.

All that said, I think there is a sensible version of the objection that might be worth considering in more detail. It is wrong for the critic of Talisse’s position to claim that everything is politics. But it may not be wrong for them to claim, more modestly, that most aspects of our lives are more political than we initially realize. In other words, that political factors and processes play a larger part in the explanation of what we do and how we do it than we initially suppose. Go back to my earlier example of sitting at my desk and drinking coffee. The political forces that make this act possible are not the ones that immediately spring to mind, but they are there if I reflect on it.

This modest proposal doesn’t undermine Talisse’s central thesis — that over-politicization crowds out the other goods of life— but if things are more political than we tend to initially suppose, it could make it quite difficult to put politics in its proper place.

3. Is this a conservative thesis?

Another objection to Talisse’s thesis is that it is inherently conservative in nature. Anyone who laments the over-politicization of human life must, in some sense, be satisfied with large swathes of the current political and social status quo. They like things the way they are and they don’t like people coming in and disrupting their contented complacency by turning everything into a political fight. As I say in the introduction, this is the objection I tend to encounter most often among my academic peers.

It might be worth noting here that there are different senses of the word ‘conservative’ at play in political discourse. This objection is focused on what might be called a ‘thin’ or ‘minimal’ form of conservatism. This ‘thin’ form of conservatism is focused purely on avoiding excessive change or disruption to the current social order, whatever that social order happens to be. In other words, it is focused on stability for stability’s sake. It doesn’t have a strong normative view as to what the ideal society should be. There is a contrasting ‘thick’ form of conservatism. This form of conservatism focuses on conserving a very specific set of social values and has a strong normative view as to what the ideal society should be. This objection is not aimed at that thicker form of conservatism.

Talisse thinks this objection to thin conservatism is a serious argument, and he agrees there is a danger that those who step back from politics are guilty of exercising political privilege. But he still insists that his stance is not a thinly conservative one. There are two main reasons for this. First, he argues that you can recognize some apolitical spaces in life and still be deeply committed to the cause of political and social justice. He is not in favor of political complacency, but he thinks it is important that we don’t burn out and become exhausted by the struggle. We have to allow for some respite from the struggle in order to appreciate and realize that the struggle is worthwhile. Second, and linked to this, he argues that over politicization could actually backfire and undermine the pursuit of justice. His argument here is a subtle one and so I will quote from him:

…failing to put politics in its place threatens to endanger the most vulnerable among us. Those who persist in overdoing democracy of course might succeed in the short run in achieving their goals, but they do so at the broader expense of contributing to a thriving democracy. This renders their success pyrrhic; in attaining the desired political result, they have helped to sustain conditions under which all political outcomes are frail and volatile. (Talisse 2019, 27)

The last sentence in this quote seems to be the crucial one. If I am reading it right, Talisse’s argument is roughly this:

(1) The point of politics is to secure some spaces in which non-political goods can be realized (derived from the crowding out argument).

(2) If everything is a subject of political debate and contest, then there is no secure space in which non-political goods can be realized.

(3) Therefore, not everything should be politicized.

I find this to be an appealing argument but it faces two problems. First, as you can see, it seems to collapses back onto the previous argument: the only way we can justifiably say that there should be an apolitical space is if it is indeed true that not everything is political. Second, even the argument is right, we might worry that some people’s lives are over-politicized against their will and hence they, unlike the more privileged among us, do not have the freedom to step back into an apolitical space. For example, some members of immigrant communities might find that all of their choices are subject to constant political scrutiny and debate. Who they choose to associate with, who they marry, the jobs they perform, the way they look (and so on) are all used as talking points in political debates. They would like nothing more than to step back and take a breather from all this politics, but they are not given the option. Someone might argue that until their plight is addressed no one should be afforded the luxury of stepping back from the fight.

The problem with this line of reasoning, of course, is that it leads us down a slippery slope. If no one can take a breather from politics until all issues of political injustice are resolved, then no one can take a breather from politics. So the question is whether it is right for some people to take a breather even if their ability to do so is a product of unjust privilege. Talisse suggests that it is okay because even if they are privileged to do so, they are not always morally guilty or blameworthy for this privilege. He goes on to argue that this is consistent with saying that these people still have a robust obligation to change the situation so that their unjust privileges are reversed (p. 28).

I guess the bottom line here is that people who think we should all have the freedom to step back from politics from time to time have to ‘put up or shut up’. In other words, they have to take some active part in changing political injustices in order to give everyone that freedom. This applies to me and Talisse, but it also applies to those who would criticize us for being conservative.

… To reiterate, I highly recommend reading the whole book. It is a thoughtful and provocative read.

__________________________________________________________________________

John Danaher is currently a senior lecturer at the National University of Ireland (NUI), Galway, where he teaches in the School of Law. He is the author of the blog “Philosophical Disquisitions,” from which this review was taken, and a new book, Automation and Utopia: Human Flourishing in a World without Work (Harvard University Press, 2019.)

(Harvard University Press, 2019.)

June 8, 2020

Thinking Our Way Through Coronavirus: Hannah Arendt’s Insights for Dark Times

(Sanjana Rajagopal’s essay below originally appeared in the Blog of the American Philosophical Association. Reprinted with permission.)

The novel coronavirus has managed to spread to all corners of the globe, altering our ways of life profoundly, bringing sickness and death everywhere it goes. Every day, the news brings reports of our ongoing battle against a pandemic the likes of which we haven’t seen in 100 years. While infected patients and tired doctors struggle against the virus in hospitals wracked by medical shortages, the rest of us have been called upon to work from home and practice social distancing.

While the injunction to stay at home initially sounds simple, it’s proven to be quite challenging for many. Not seeing friends, not going out, and not attending in-person classes grates on our sensibilities as social animals. Social distancing is additionally difficult for those who suffer from mental illnesses like depression or anxiety. Suicide hotlines have already seen a surge in calls as people feel the acute impact of forced isolation. Even for those who are not clinically diagnosed with depression or anxiety, the 24-hour media cycle is overwhelming, filled with misinformation and idle talk.

Arendt was no stranger to hard times. A German-born Jew who studied philosophy with Martin Heidegger and Karl Jaspers, she fled the Nazi menace for the United States in 1941. In Men in Dark Times, published in 1968 during another time of upheaval, she briefly considers mental escapism as a method of surviving a turbulent world and decides against it:

To what extent do we remain obligated to the world, even when we have been expelled from it, or have withdrawn from it? […] How tempting it was, for example, to simply ignore the intolerably stupid blabber of the Nazis. But seductive though it may be to yield to such temptations and to hole up in the refuge of one’s psyche, the result will always be a loss of humanness, along with the forsaking of reality.

Thinking, when employed in this way, is not useful to us or good for us. How many of us stop paying attention when President Trump or another demagogue begins to speak, only to retreat into ourselves and our own thoughts? Arendt decries this kind of alienation from the world. Thinking must not become a hiding place into which we frequently withdraw when the world tires us with all its ills and evils. Instead, Arendt calls upon us to take on the most difficult attitude of exercising love for the world (amor mundi), in spite of all evil and suffering contained in it.

While some of us risk disappearing into our thoughts and withdrawing from the world, others are not able to be alone with our thoughts. We find it unbearable and turn to distractions—binge-watching YouTube videos or endlessly scrolling through social media. This choice is also a mistake. We must instead find a way to be with our thoughts without disconnecting from the world.

What Arendt teaches us in the era of COVID-19 social distancing is to think about thinking in the right way. We can begin to do this by recognizing a crucial distinction between the existential states of solitude and loneliness—a distinction Arendt introduces in her final work, The Life of the Mind. Solitude is the state in which we only have ourselves for company, and lack human companionship. Loneliness is the state in which we do not even have ourselves for company.

After our Facetime calls with our friends and relatives end, we have only our own company to look forward to. This can seem rather daunting—however, the sooner we realize that we can never truly be alone as long as we are engaged in thinking, the better. Thinking, as Arendt puts it (crediting Plato’s Gorgias), is the “soundless dialogue of the I with itself.” When I think, I become two-in-one, and I am able to view myself as an interlocutor. While I cannot withdraw into this soundless dialogue forever, I can bring its fruits back to the world, where they can have real impact. The imperative to “think what we are doing” suggests that thought must always return to the world. Furthermore, thought, as Arendt acknowledges in The Human Condition, can be translated into art, literature, music, and other things which can comfort and contribute to the human experience.

There is yet another sense in which Arendt extols the importance of thinking: It is meant to be what staves off evil. Though thinking on its own cannot eradicate evil, thoughtlessness can result in nothing but evil, as Adolf Eichmann and many unthinking others throughout history demonstrate. In modern times, we are privy to a full range of moral and social issues only exacerbated by COVID-19. The pandemic has disclosed to us our deeply problematic attitudes toward the old and the disabled and toward the values we place on labor and service.

Never has Arendt’s problem with the term “political economy” been so clear as it has now, when the two seem to be more at odds than ever. Politics on her view cannot just concern itself with economic instrumentality: It must be viewed as valuable in its own right, and as the original and most life-giving activity of the public realm. Of course, Arendt thinks the public realm has already been in decline for a long time; the rise of mass society and our individualistic retreat into the private realm of the household have ensured that. The pandemic threatens the collapse of the public realm if everything’s public significance is reduced to its contribution to the economy or sheer survival.

Now more than ever, we must engage in the soundless dialogue with our inner self, and ask the question, “Can I live with myself?” Can we live with ourselves if we sacrifice the old and vulnerable, and especially if we do so to save the economy? Even Adam Smith denounced naked self-interest and advocated the development of one’s sympathetic imagination. Like Arendt, he reminds us that we must think about what we are doing because we have to live with ourselves. In The Life of the Mind, Arendt asks who would want to be friends with a murderer—and answers her own question by saying that not even the murderer himself would be a good candidate.

Thinking, now more than ever, is the tool we need to move beyond apathy, boredom, or loneliness. In her foreword to the 2018 edition of The Human Condition, Danielle Allen writes about what Arendt’s insights offer for our era:

Life moves faster than science, whether natural or social. Factories close. People find themselves out of work and smitten by depression. People die. People go to prison over the many years it takes the scientist to hypothesize, collect data, test, confirm or disconfirm, and replicate. And so it goes on. When we confront the hardest social problems—like mass incarceration or economic disruption as occasioned by globalization, or climate change—we need to accelerate the pace of our acquisition of understanding. We have to use every available tool to think about what we are doing.

In order to come up with novel solutions to the problems that arise in our era, we will have to engage in what Arendt calls “thinking without a banister.” We must discard the guard-rails limiting our thought so that we can face the new challenges of our time with creativity and aplomb. Epoch-defining events like the COVID-19 pandemic require epoch-defying ways of thinking.

In The Human Condition, Hannah Arendt famously compares the world to a table that people gather around: a table that relates and separates people at the same time. Arendt can’t tell us how to cope with COVID-19, but she does give us back the art of thinking, an art which will help us reclaim our world and rearrange the table, ravaged as it is by forces both within and beyond our control. So long as we retain the ability to think— though, not going to the extent of losing ourselves in our thoughts and always coming back to the world in the end—we are never truly alone. Finally, Arendt compels us to look forward with hope— noting that, “Even in the darkest of times, we have the right to expect some illumination.”

_____________________________________________________________________________

Sanjana Rajagopal (@SanjanaWrites) is a PhD student in philosophy at Fordham University

June 4, 2020

Understanding Nihilism: Evaluative and Practical

[image error]The Nihilist by Paul Merwart (1882)

“Understanding Nihilism: What if nothing matters?”

©John Danaher (Reprinted with Permission)

John Danaher is currently an academic and senior lecturer at the National University of Ireland (NUI), Galway, where he teaches in the School of Law. He is the author of the extraordinarily erudite blog “Philosophical Disquisitions,” from which this essay is taken, and a new book Automation and Utopia: Human Flourishing in a World without Work[image error] (Harvard University Press, 2019.)

We spend so much of our time caring about things. Thomas Nagel described the phenomenon quite nicely:

[People] spend enormous quantities of energy, risk and calculation on the details [of their lives]. Think of how an ordinary individual sweats over his appearance, his health, his sex life, his emotional honesty, his social utility, his self-knowledge, the quality of his ties with family, colleagues, and friends, how well he does his job, whether he understands the world and what is going on in it. Leading a human life is a full-time occupation, to which everyone devotes decades of intense concern. (Nagel 1971, 719-720.)

Why so much intense concern? What if nothing we do really matters? What, in other words, if nihilism is true?

That’s the question I want to look at in this post. I do so with the help of Guy Kahane’s recent paper ‘If nothing matters’, which is an excellent and insightful exploration of the topic. It doesn’t defend the nihilistic view itself, but it does clarify what it means to be a nihilist and what the implications of the nihilistic view might be. In the process, it takes issue with a strange trend in contemporary metaethics which assumes that if nihilism is true, then nothing about our day-to-day lives would change all that much. Kahane finds this implausible and tries to explain why.

In what follows, I discuss the key elements of Kahane’s analysis. I start by explaining what nihilism is, and distinguishing between its evaluative and practical versions. I then look at the oddly deflationary attitude of some metaethicists towards the truth of nihilism. And I close by considering Kahane’s critique of this deflationary view. As we shall see, Kahane argues that if we come to believe that nihilism is true, then we are unlikely to be able to go about our daily business much as we did before. On the contrary, we can expect much to change.

1. What is Nihilism Anyway?

Nihilism is the view that nothing matters. It comes in two distinct forms. The first is evaluative nihilism, which Kahane describes like this:

Evaluative Nihilism: Nothing is good or bad — or — All evaluative propositions are false.

Remember that time a few weeks back when you were walking to work, it was raining heavily, you stubbed your foot and ripped the sole off your shoe, then got splashed by a car and ended up being late and soaking wet? At the time, you said that this was ‘bad’. If evaluative nihilism is correct, you were wrong to say this. Nothing is really good or bad because evaluative propositions that ascribe those properties to particular events or states of affairs are always false. And this is just to use a trivial example. Evaluative nihilism also applies to more serious evaluative propositions like ‘murder is bad’ or ‘pleasure is good’. None of these claims is true.

Evaluative nihilism is the core of nihilism. But the typical belief is that it entails another form of nihilism:

Practical Nihilism: We have no reasons to do, want, or feel anything.

The idea here is that values are what should motivate action, desire, and emotion. The badness of being wet and late for work should motivate me to avoid this outcome in the future. It should motivate me to leave earlier, wear more sensible raingear and footwear. But if nothing is really good or bad all that motivational force is sapped away. This is a normative claim, not a psychological one (we’ll touch upon psychology later). It is about having reasons for doing, wanting, and feeling. Practical nihilism strips us of all such reasons.

Practical and evaluative nihilism often go hand-in-hand, but they are separable. Kahane argues that evaluative nihilism only implies practical nihilism if you accept a consequentialist view of practical reason. If there are non-consequentialist constraints on action, then the goodness or badness of an outcome or state of affairs may not always be decisive in determining whether you have reasons for action. That said, it is worth treating the two forms of nihilism together since many who worry about the implications of nihilism worry about both.

But why do they worry? There are some misconceptions about the consequences of accepting nihilism. Many authors speak of nihilism in hushed and terrified tones. The idea is that if we really believed in nihilism we would be overwhelmed by the emptiness of our lives and driven to despair and suicide. In short, if nihilism were true then our lives would be worse. This is to misunderstand nihilism. To use the classic retort: if nothing matters, then it doesn’t matter that nothing matters. Or, in more evaluative terms:

No Cause for Despair: If nihilism is true, then its truth couldn’t make our lives worse (or better) for the simple reason that nihilism entails that you cannot say that a particular state of existence is worse or better.

Of course, how we react to the truth of nihilism is an empirical matter. It may be that some people do feel despair at the thought that nothing matters. But this is arguably because they implicitly cling to non-nihilistic views. They assume that things can really be better or worse for them; that they can have reasons for their despair. If nihilism is true, neither of these things is actually possible.

2. Deflationary and Conservative Metaethical Nihilism

Now that we have a firmer grasp of nihilism we can consider some broader issues. One is the role of nihilism in contemporary metaethical debates. Metaethics is the branch of moral philosophy that is concerned with the ontology and epistemology of moral claims. Moral claims are all about what is good and bad and right and wrong. Some metaethicists are cognitivists, who believe that moral claims are capable of being objectively true or false (i.e. that things really are good/bad and right/wrong). Non-cognitivists reject this view. There are many different schools of non-cognitivism, but the one that is the focus of Kahane’s analysis is that of the error theorists.

Error theorists hold that our entire moral discourse rests on a mistake. The mistake is that when we say something like ‘Torture is bad’ we think we are making a claim like ‘Water is H2O”, but we are wrong. The latter statement is capable of being objectively true or false; the former is not. In short, our moral discourse is in error: there are no objective values (or rights and wrongs). Famous error theorists include JL Mackie and Richard Joyce.

Described thusly, error theorists seem to embrace nihilism. You might think this would cause them to cast off ordinary moral practice. But strangely enough they do not. Many of them adopt an oddly deflationary attitude toward their metaethical insights. Yes, it is true that there is no objective good or bad or right or wrong, but this shouldn’t change much about how we live our lives. Consider the following passage from Mackie:

The denial of objective values can carry with it an extreme emotional reaction, a feeling that nothing matters at all… Of course this does not follow; the lack of objective values is not a good reason for abandoning subjective concern. (Mackie 1977, 34)

Mackie’s suggestion here is that even if his error theory is correct it is possible for people to care about things and to continue to live their lives as they always have. This is reinforced elsewhere in his work when he talks about the practical utility of continuing to behave in a ‘moral’ way. As some have put, we should be error theorists in the seminar room; but practical evaluative realists in the streets.

Kahane thinks this deflationary attitude is itself in error. It fails to take seriously the implications of evaluative and practical nihilism. As he sees it, in order for us to follow Mackie’s lead, it must be possible for us to do two things after coming to accept the truth of nihilism:

A. We must continue to have the subjective concerns we used to have before coming to believe in nihilism (i.e. believe that some things are worthwhile, not worthwhile etc).

B. We must be able to use these concerns to guide our actions (i.e. engage in instrumental reasoning).

While Kahane thinks it might be possible for us to conform to something like instrumental reasoning, he is much less convinced that we will continue to have the same subjective concerns. He has an argument for this which we will consider next.

3. Against the Deflationary View

Kahane’s argument is somewhat elaborate. I’ll describe a simplified version. The simplified version focuses on two claims about our normative psychology, i.e. by what should happen if we come to believe in the truth of nihilism. The empirical reality might be somewhat different, and Kahane concedes as much, but he thinks his argument works off a number of basic truisms about how our psychology functions.

The two main claims are as follows:

Belief Loss

Covariance thesis: Our subjective concerns covary with our evaluative beliefs in such a way that the loss of the latter is likely to result in the loss of the former.

These claims then get incorporated into an argument which runs something like this:

(1) If we are to continue to live as we did before, then we need to retain our subjective concerns.

(2) If we come to believe in nihilism, we will probably lose many (possibly all) of our evaluative beliefs.

(3) If we lose many (possibly all) of our evaluative beliefs, then we will probably lose our subjective concerns.

(4) Therefore, if we come to believe in nihilism, we will probably not continue to live as we did before.

This is a probabilistic argument. It is about what is likely to happen rather than what will definitely happen. How can its key premises be defended?

We’ll start with the second premise, which is the belief loss claim. The first obvious point in its favor is that evaluative nihilism straightforwardly entails the falsity of evaluative beliefs. If no evaluative proposition is true, then any beliefs we have in such evaluative propositions must be false. The question is whether this subsequently implies that we will lose our evaluative beliefs. The logical implication is straightforward, but human psychology does not always track logic. It is conceivable that people could hold contradictory beliefs in their heads at the same time. But this is an unstable state of affairs. Over time, we might expect them to favor one or the other. Kahane uses a thought experiment to illustrate his thinking:

Suppose Bob believes that two people he knows (Anne and Claire) are witches. But suppose you manage to convince Bob that witches do not exist, i.e. that no one has been or ever will be a witch. Will he continue to believe that Anne and Claire are witches? It is difficult to see how, at least in the long term. His acceptance of the general proposition (“there are no witches”) is going to be in constant tension with the more specific propositions (“Anne is a witch” and “Claire is a witch”). Eventually, something would have to give.

This certainly seems plausible. And if we expect this to happen in the case of witch-belief, it seems natural to expect it to happen in the case of nihilism. After all, the two scenarios are structurally similar. If I come to believe in the general proposition “Nothing matters”, it’s hard to see how I could continue to believe in specific propositions like “My job matters”. It is, of course, possible that I could waver in my commitment to nihilism, believing in it at times and disbelieving in it at others. This might cause me to oscillate back and forth between believing that my job matters and believing that it doesn’t. But if I am unwavering in my commitment, my other evaluative beliefs should slowly ebb away.

This brings us to the third premise which holds that this loss of evaluative belief should impact upon my subjective concerns. Kahane doesn’t give an elaborate argument for this view. He seems to think the covariance of evaluative belief is a basic truism of our psychology. To reject it, one would have to embrace an epiphenomenalist view of evaluative belief. This would hold that evaluative belief has no causal impact on our ‘pattern of concerns’. There may be some materialist approaches to the philosophy of mind that accept this notion, but these approaches have their costs.

If the second and third premises are correct, then the conclusion follows. The deflationary view of error theorists like Mackie looks to be implausible. Believing in nihilism is likely to have a knock-on effect on our lives. We probably couldn’t be nihilists in the seminar room and evaluative realists in the streets. We could only be one of these things.

4. Conclusion

… Kahane’s argument seems right to me, at least when it is interpreted within its own self-imposed constraints. Kahane deals with normative psychology, not empirical psychology. It would be interesting to have more empirical evidence about the effects of nihilistic belief on someone’s behavior, but I suspect it would be difficult to conduct any tests on this. I also think that further engagement with the epiphenomenalist view would be interesting.

June 3, 2020

White Privilege

I have privilege as a white person because I can do all of these things without worry:

I can go birding (#ChristianCooper)

I can go jogging (#AmaudArbery)

I can relax in the comfort of my own home (#BothemSean and #AtatianaJefferson)

I can ask for help after being in a car crash (#JonathanFerrell and #RenishaMcBride)

I can have a cellphone (#StephonClark)

I can leave a party to get to safety (#JordanEdwards)

I can play loud music (#JordanDavis)

I can sell CDs (#AltonSterling)

I can sleep (#AiyanaJones)

I can walk from the corner store (#MikeBrown)

I can play cops and robbers (#TamirRice)

I can go to church (#Charleston9)

I can walk home with Skittles (#TrayvonMartin)

I can hold a hair brush while leaving my own bachelor party (#SeanBell)

I can party on New Years (#OscarGrant)

I can get a normal traffic ticket (#SandraBland)

I can lawfully carry a weapon (#PhilandoCastile)

I can break down on a public road with car problems (#CoreyJones)

I can shop at Walmart (#JohnCrawford)

I can have a disabled vehicle (#TerrenceCrutcher)

I can read a book in my own car (#KeithScott)

I can be a 10yr old walking with our grandfather (#CliffordGlover)

I can decorate for a party (#ClaudeReese)

I can ask a cop a question (#RandyEvans)

I can cash a check in peace (#YvonneSmallwood)

I can take out my wallet (#AmadouDiallo)

I can run (#WalterScott)

I can breathe (#EricGarner)

I can live (#FreddieGray)

I CAN BE ARRESTED WITHOUT THE FEAR OF BEING MURDERED (#GeorgeFloyd)

White privilege is real. Take a minute to consider a black person’s experience today.

#BlackLivesMatter

June 1, 2020

The Serenity Prayer: A Brief Analysis

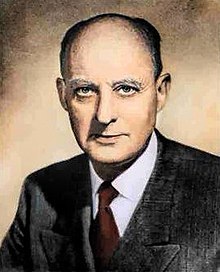

[image error]Reinhold Niebuhr (1892 – 1971)

The Serenity Prayer is the common name for a prayer written by the American theologian Reinhold Niebuhr. The best-known form is:

God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change,

Courage to change the things I can,

And wisdom to know the difference.

I’ve never thought deeply about the prayer—although it certainly came up in the classes I taught. However, the video below by the philosopher Luc Bovens titled “Want a Meaningful Life? Learn to Control Your Mind,” got me to thinking more about it. Bovens believes that the prayer presents a false dichotomy. He argues that there is a space between serenely accepting and courageously changing—and that space is best filled by hope. Hope lies between active change and passive acceptance.

Now consider how this applies to Bovens’ topic in the video—living a meaningful life. We cannot act so as to guarantee that life is meaningful, but we shouldn’t just accept that it is meaningful either. What we can do is act in the hope that life is meaningful while accepting that we can’t be assured that it is. So hoping involves both active and passive components. And this is an alternative to the choices offered by the prayer’s false dichotomy.

Here is Bovens explaining this.

The Serentity Prayer: A Brief Analysis

Reinhold Niebuhr (1892 – 1971)

Reinhold Niebuhr (1892 – 1971)

The Serenity Prayer is the common name for a prayer written by the American theologian Reinhold Niebuhr. The best-known form is:

God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change,

Courage to change the things I can,

And wisdom to know the difference.

I’ve never thought deeply about the prayer—although it certainly came up in the classes I taught. However, the video below by the philosopher Luc Bovens titled “Want a Meaningful Life? Learn to Control Your Mind,” got me to thinking more about it. Bovens believes that the prayer presents a false dichotomy. He argues that there is a space between serenely accepting and courageously changing—and that space is best filled by hope. Hope lies between active change and passive acceptance.

Now consider how this applies to Bovens’ topic in the video—living a meaningful life. We can’t act so as to guarantee that life is meaningful, but we shouldn’t just accept that it is meaningful either. What we can do is act in the hope that life is meaningful while accepting that we can’t be assured that it is. So hoping involves both active and passive components. And this is an alternative to the choices offered by the prayer’s false dichotomy.

Here is Bovens explaining this.

May 28, 2020

The Disconsolation Of Philosophy

Boethius teaching his students

Boethius teaching his students

(This essay originally appeared at 3 Quarks Daily. Reprinted with permission.)

By Joseph Shieber

This semester I’ve been teaching a first-year seminar entitled “Propaganda”. It is, unfortunately, a very timely topic …

Having taught the course over a few iterations now, I’ve had an opportunity to observe a few different reactions on the part of my students to the bit of philosophy that we engage in in the course. There’s some dismissiveness, of course, on the part of some of the students, but I’ve also noted surprise on the part of some of the students in response to my own stance about how modest the fruits of philosophy often are.

I think that many of the students expect me to claim more for philosophy and what it can achieve. Perhaps they expect me to declaim dramatically that there is no such thing as truth. Instead, I’m more than happy to assert a variety of truths: that human-caused global warming is a genuine phenomenon, for example, or that vaccines don’t cause autism, or that human beings are the result of evolution by natural selection. But I also take pains to try to expose the assumptions on which those assertions of mine rely. And I also try to trace how different assumptions — including about what counts as good evidence — might lead someone to have different beliefs.

What I hope to achieve with the way that I deploy philosophy in the course is to get students to appreciate the value of intellectual humility. I want them to recognize how rigorous and exacting intellectual humility can be. It involves excavating the hidden premises that underlie our beliefs. It is also compatible with maintaining our belief in the truth of those premises, while at the same time acknowledging that those who accept different, incompatible premises, will arrive at different beliefs.

In the course, I am open about my own positions, but I encourage students to defend their own views, even if those views conflict with my own. I do my best to evaluate them not on whether they ultimately agree with me, but whether they do a good job of supporting their own positions on the basis of their own starting premises.

This makes for a challenging course for the students. Rather than telling them what they ought to believe, I encourage them to criticize, but also to defend their own opinions — just so long as they are able to shape those opinions into a coherent position.

One of the puzzling aspects of the course for the students is to recognize that two coherent positions, each of which enjoys a strong internal logic, can be mutually incompatible. Given that the two positions conflict, they cannot both be correct. But given their coherence and strong internal logic, it would not be possible to convince someone who is committed to one of the positions that she ought to abandon it.

This is puzzling because students often come in to a course with the expectation that the smarter and more logical a thinker is, the more likely they are to be correct. And it can be jarring to appreciate that sometimes two mutually opposed thinkers can both be incredibly smart and logically adept — since at most one of them can possibly be correct!

In particular, as I point out to my students, this demonstrates why it is that philosophy invites intellectual humility. The history of philosophy is replete with a number of cases of brilliant thinkers who created complicated, coherent philosophical systems — that are unfortunately mutually incompatible with the equally complicated, coherent philosophical systems created by other, equally brilliant thinkers.

I think it’s important to emphasize the connection between philosophy and intellectual humility, because philosophy has a long tradition of intellectual hubris, of overselling the value of philosophy. Consider the case of Boethius, a Roman aristocrat who lived in the last decades of the fifth century and the early decades of the sixth century C.E. Boethius achieved a high position in the court of Theodoric the Great, the Ostrogoth who ruled a kingdom stretching from Spain to the Adriatic, and including all of Italy. Due to court intrigue, Boethius was accused of sorcery and treason, imprisoned, and eventually executed in 526 C.E.

In his masterwork, The Consolations of Philosophy[image error], written while in prison, Boethius seeks to comfort himself in his misfortune, through an imagined dialogue with a lady who serves as the personification of Philosophy. He consoles himself with the idea that the riches he has gained from his study of philosophy far outweigh his misfortune. Despite his imprisonment, no external force can remove him from “the chamber of [his] mind wherein [Philosophy] once placed not books but that which gives books their value, the doctrines which [those] books contain”.

We can distill this out as the Consolation of Philosophy principle, or simply Consolation Principle. According to the Consolation Principle, the philosopher’s mind, by itself and without relying on anything external to it, is sufficient for achieving something of value. In fact, in The Consolation of Philosophy, Boethius seems to go even further and claim that everything of real value is attainable by the mind, acting alone. But let’s not deal with that strong version of the Consolation Principle; let’s just look at the weaker version, which just states that *something* of real value is attainable by the mind, acting alone.

Against this Consolation Principle, I want to suggest that philosophy actually teaches us what you might call the Disconsolation Principle. Philosophy actually shows that the mind, acting by itself and without relying on anything external to it, is insufficient for achieving something of value. In other words, it seems to me that, when you consider the nature of our mental resources themselves, you’re left with the inescapable position that the Consolation Principle just isn’t very plausible.

In order to appreciate this, it might help to begin by considering the nature of deductive reasoning. Valid deductive reasoning is reasoning that establishes its conclusions inescapably, given the truth of the premises on which those conclusions rest.

For example, if I know that the moon is made of green cheese and that green cheese is denser than brie, then I can conclude that the moon is denser than brie. The force of the argument rests on the fact that, if its premises are true, there is no way for its conclusion to be false.

But a great deal rests on the phrase “if its premises are true”. When I teach logic, I needn’t concern myself with the truth of the premises of the arguments that my students and I evaluate. In logic, we’re interested with the structures of arguments — whether those arguments are valid. And in deductive logic, we can evaluate the validity of arguments without concerning ourselves with whether the premises of those arguments are actually true.

Now, of course, in other philosophy courses this is not the case. In other philosophy courses, we might want to evaluate whether humans have free will, or whether knowledge requires belief, or whether morally right action sometimes deviates from the maximization of expected utility. In such cases, though we certainly want to evaluate valid arguments, we also need to consider the truth of the premises that figure in such arguments.

When doing philosophy, in other words, the validity of the arguments that we employ is at best a necessary condition for achieving greater philosophical understanding. Achieving such understanding will also require that we assess the truth of the premises that figure in those arguments. Does freedom require the possibility to have done otherwise? Is knowledge the most basic factive attitude? Does right action require that we treat persons always as ends in themselves, rather than as means to an end?

But now here’s the problem for the Consolation Principle — and the reason why I find the Disconsolation Principle far more likely to be apt. It just doesn’t seem plausible to me that we can, solely using the resources of our own minds, evaluate the truth of the premises that figure in those philosophical arguments.

Let me clarify two important elements of this last claim.

First, the “we” in that claim is important. When I make that claim, I’m not claiming that nobody can, solely using the resources of their own mind, evaluate the truth of the premises that figure in those philosophical arguments. My claim is a weaker one: it’s that, if anybody can exert such feats of mental self-sufficiency, nevertheless such abilities are extremely uncommon.

So when I say that it’s more plausible that we cannot, solely using the resources of our own minds, evaluate the truth of the premises of philosophical arguments, what I mean is that the vast majority of people, were they even to care about or attempt to evaluate the premises of philosophical arguments, would not be able to do so alone and unaided.

Second, it’s important to understand what “solely using the resources of our own minds” means. By that I mean, to a first approximation, “using what seems to us, on considered and solitary reflection, to be the case”. I think the first approximation is enough for our purposes. Using the resources of your own mind means not conducting an empirical investigation, not consulting the investigations of others, and also not consulting the reasoning of others, or subjecting your own reasoning to the critical evaluation of others.

Given this way of understanding these two elements, it seems to me extremely plausible that most people would not be capable of assessing, in any satisfactory way, the truth of philosophical premises solely using only the resources of their own minds. (And yes, I include myself among those “most people”.)

Perhaps, though, I’ve been holding the Consolation Principle to an unreasonable standard. I’ve been assessing whether the unaided mind is sufficient to evaluate significant truths. And perhaps that’s too much to ask. But I think that there are reasons to think that the Consolation Principle, more generally, actually offers us little consolation.

To see this, take perhaps the easiest scenario for which the Consolation Principle might apply: even if you’re left solely to your own devices, your mind is sufficient for keeping you entertained. Once you realize that the phrase “even if you’re left solely to your own devices” doesn’t include your smartphone, you’ll probably already be inclined to question the plausibility of the Consolation Principle, even in the case that involves merely keeping yourself entertained. And evidence involving much more dramatic cases, such as the ill-effects of solitary confinement, for example, suggest that such skepticism is warranted.

So here’s where we are. When you consider the limitations of our mental resources, it seems plausible to suggest that the unaided mind is — or, at least, most unaided minds are — not capable of achieving very much.

In this way, the Disconsolation Principle is something of a return to an even earlier role for philosophy: that of gadfly to the intellectually self-satisfied. In the Apology, Socrates recounts having questioned a politician acclaimed for his wisdom and having come away thinking that “I am better off than he is – for he knows nothing, and thinks that he knows. I neither know nor think that I know.”

Rather than consoling us about what we can achieve alone through the efforts of our minds, in other words, philosophy does better when it reminds us to be more modest about the extent of our abilities.

May 25, 2020

Critical Thinking & COVID-19 XIII: Death Analogies

“Critical Thinking & COVID-19 XIII: Death Analogies”

by Professor Michael LaBossiere (Reprinted with permission)

One stock argument against social distancing and other restricted responses to the pandemic is to conclude that these measures should not be taken because we do not take similar approaches to comparable causes of death. Put a bit more formally, the general argument is:

Premise 1: Another cause of death kills as many (or more) people than COVID-19.

Premise 2: We do not impose social distancing and other such restrictive measures to address this cause of death.

Conclusion: We should not impose social distancing and other such restrictive measures to address COVID-19.

Those making the argument often use the flu as an analogous cause of death, but people have also made comparisons to automobile accidents, suicides, heart disease, drowning in pools and so on. While the specific arguments are presented in various ways, they are all what philosophers call an argument from analogy.

Informally speaking, an argument by analogy is an argument in which it is concluded that because two things are alike in certain ways, they are alike in some other way. More formally, the argument looks like this:

Premise 1: X and Y have properties P, Q, R.

Premise 2: X has property Z.

Conclusion: Y has property Z.

X and Y are variables that stand for whatever is being compared, such as causes of death. P, Q, R, and are also variables, but they stand for properties or features that X and Y are known to possess, such as killing people. Z is also a variable and it stands for the property or feature that X is known to possess, such as not being addressed with social distancing. The use of P, Q, and R is just for the sake of the illustration—the things being compared might have many more properties in common.

An argument by analogy is an inductive argument. This means that it is supposed to be such that if all the premises are true, then the conclusion is probably true. Like other inductive arguments, the argument by analogy is assessed by applying standards to determine the quality of the logic. Like all arguments, there is also the question of whether the premises are true.

The strength of an analogical argument depends on three factors. To the degree that an analogical argument meets these standards, it is a strong argument.

First, the more properties X and Y have in common, the better the argument. This standard is based on the commonsense notion that the more two things are alike in other ways, the more likely it is that they will be alike in some other way. It should be noted that even if the two things are very much alike in many respects, there is still the possibility that they are not alike regarding Z. This is one reason why analogical arguments are inductive.

Second, the more relevant the shared properties are to property Z, the stronger the argument. A specific property, for example, P, is relevant to property Z if the presence or absence of P affects the likelihood that Z will be present. It should be kept in mind that it is possible for X and Y to share relevant properties while Y does not actually have property Z. Again, this is part of the reason why analogical arguments are inductive.

Third, it must be determined whether X and Y have relevant dissimilarities as well as similarities. The more dissimilarities and the more relevant they are, the weaker the argument.

These can be simplified to a basic standard: the more alike the two things are in relevant ways, the stronger the argument. And the more the two things are different in relevant ways, the weaker the argument. So, using these standards let us consider the cause of death analogy.

One thing that all causes of death do have in common is that they are causes of death—this is true of everything from swimming pools to the flu to COVID-19. Obviously, different causes of death will be more or less similar to COVID-19 deaths and a full consideration would require grinding through each argument to see if it holds up. In the interest of time, I will consider two main categories of causes of death that should encompass most (if not all) causes.

One category of causes of death consists of those that cannot be addressed by social distancing and the other science-based approaches to COVID-19. These include such things as suicide, traffic fatalities and swimming pool deaths. We obviously do not use such methods to address these causes because they would not work. As such, arguing that because we do not use social distancing to combat traffic deaths so we should not use it to combat COVID-19 would be a terrible analogy. To use an analogy, this would be like arguing that since we do not use airbags and seat belts to address COVID-19, we should not use them to reduce traffic fatalities. This would be bad reasoning.

To be fair, a person could argue that what matters is not the specific responses but the degree of the response—that is, since we do not have a massive and restrictive response to traffic fatalities we should not have a massive response to COVID-19. While it is rational to proportion the response to the threat, the obvious reply to this argument is to point out that we do have a massive and restrictive response to traffic fatalities. Vehicles must meet safety standards, drivers must be licensed, there are volumes of traffic laws, traffic is strictly regulated with signs, lights and road markings, and the police patrol the roads regularly. Even swimming pools are heavily regulated in the United States—for example, fences and self-locking gates are mandatory in most places. Somewhat ironically, drawing an analogy to things like traffic fatalities supports massive and restrictive means of addressing COVID-19.

Horribly, the best way to argue against a strong response to COVID would be to find a cause of death on the scale of COVID-19 that we as a nation do little about and then argue that the same neglect should be applied to COVID-19. Poverty and lack of health care would certainly be two good examples—but the risk of such a tactic is that it might lead people to conclude not that we should be negligent about COVID-19 prevention but that we should have a massive response to these other causes of death.

The second category of deaths consists of causes that could be addressed using the same methods used to address COVID-19. The common flu serves as an excellent example here—the same methods that work against COVID-19 would also work against the flu. As many argued, even in a bad flu year life remains normal—no social distancing, no closing of businesses, no mandatory masks. While this analogy does seem appealing, it falls apart quickly because of the relevant differences between COVID-19 and the common flu.

While the death rate for COVID-19 is not yet known, the best available estimate is that it kills 3-4% of those who are infected—though there is considerable variation based on such factors as age, access to health care, and underlying health conditions. In contrast, the flu has a mortality rate well below .1%. It still kills too many people, but it is vastly less dangerous than COVID-19. So, it makes sense to have a more restrictive and extensive response to something that is far more dangerous. We also do have measures in place against the flu: people are urged to take precautions and flu shots are recommended. If COVID-19’s threat drops down to the level of the seasonal flu, then it would make sense to apply similar levels of response. Likewise, if a dangerous strain of flu emerges again, then it would make sense to step up our restrictions.

In closing, this discussion does lead to a matter of ethics and public policy. As those who make the death analogies note, we collectively tolerate a certain number of preventable deaths. We must seriously address the issue of determining the acceptable number of deaths from COVID-19 and match our response to that judgment. And we should not forget that we might be among those tolerated deaths.

Stay safe and I will see you in the future.

May 22, 2020

Arthur C. Brooks: “Three Equations for a Happy Life”

Arthur C. Brooks recently published “The Three Equations for a Happy Life, Even During a Pandemic” in “The Atlantic.” I generally don’t like his work as he is religiously and politically conservative—if not fanatically so. He was president for a decade of the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank and he claims to have been converted to Catholicism after the Virgin Mary appeared to him. I’m not making this up! (How smart people can be so delusional always amazes me. veridical His subjective experience is almost certainly not a veridical account of objective reality.)

Still, I was willing to read someone whose critical thinking skills have been thrown into doubt by his biography, and whose views I won’t likely agree with. Yet I found this to be a fine essay and a good summary of much of the recent work on human happiness.

Brooks teaches a class on happiness at the Harvard Business School. He begins by noting that the “scientific study of happiness has exploded over the past three decades.” The article attempts to summarize what science has found on the topic. (Note. I’ve discussed happiness many times, especially in my summary of the Harvard psychiatrist George Vaillant’s book: Triumphs of Experience: The Men of the Harvard Grant Study.) In order to explain the science, Brooks introduces 3 equations.

1: SUBJECTIVE WELL-BEING = GENES + CIRCUMSTANCES + HABITS

Equation 1 summarizes a vast amount of literature on subjective well-being (SWB.) Social scientists prefer the term SWB because it captures a longer-lasting sense of happiness than the common usage which might refer to a temporary good mood or other fleeting feelings.

Regarding genes, the research strongly suggests that about 50% of our happiness “set point” or baseline of happiness is genetic. Regarding your circumstances, the research is inconclusive with estimates of its role in SWB as anywhere from 10% to 40%. Whatever the role of circumstances though their effect never lasts very long. When we get promoted, win the lottery, marry or get divorced, we tend to adjust to our new circumstances quickly. While genes aren’t under our control, and circumstances often aren’t either, habits are under our control. To better understand habits, we need Equation 2.

2: HABITS = FAITH + FAMILY + FRIENDS + WORK

Brooks argues, on his summary of thousands of academic studies, that SWB comes from human relationships, productive work, and the transcendental elements of life. (These are very close to Vicktor Frankl’s components of the meaningful life.)

Regarding faith, Brooks says that “many different faiths and secular life philosophies can provide this happiness edge. The key is to find a structure through which you can ponder life’s deeper questions and transcend a focus on your narrow self-interests to serve others.” Regarding family and friends “the key is to cultivate and maintain loving, faithful relationships with other people.”

Regarding work, the literature shows that productive work is part of SWB. While some jobs are better than others “most researchers don’t think unemployment brings anything but misery.” Brooks argues that meaningful work can be of almost any kind as long as it gives you a sense “that you are earning your success and serving others.” He also notes that money doesn’t buy SWB because we never think we have enough of it. (He omits saying that being poor is bad for you SWB. SWB depends on having a minimal amount of wealth.)

So there you have it. A good life consists of loving relationships, productive work and having a purpose in life. This echoes Aristotle on the good life.

3: SATISFACTION = WHAT YOU HAVE ÷ WHAT YOU WANT

Brooks’ final equations emphasize satisfaction which for him is being satisfied with what you have and caring less about what you want. (To paraphrase the Stoics, happiness isn’t getting what you want but wanting what you get.) While I agree, I would note that it is easy for a wealthy upper-class person like Brooks who has so much to say this. Much harder for the poor and oppressed to be content. Still, I agree that the key to happiness—if you have a reasonable amount of wealth—is to focus more on the numerator of Equation 3 rather than the denominator. Otherwise, we may find ourselves on the hedonic treadmill.

________________________________________________________________________

Below are some of my previous posts related to happiness.

May 20, 2020

Critical Thinking & COVID-19: Argument Against Expertise

“Critical Thinking & COVID-19: Argument Against Expertise”

by Professor Michael LaBossiere (Reprinted with permission)

In a previous essay, I went over the argument from authority and the standards to use to distinguish between credible and non-credible experts. While people often make the mistake of treating non-experts as credible sources, they also make the mistake of rejecting credible experts because the experts are experts. This sort of fallacious reasoning is worthy of a name and the obvious choice is “argument against expertise.” It occurs when a person rejects a claim because it is made by an authority/expert and has the following form:

Premise 1: Authority/expert A makes claim C.

Conclusion: Claim C is false.

While experts can be wrong, to infer that an expert is wrong because they are an expert is obviously absurd and an error in reasoning. To use a geometry example, consider the following:

Premise 1: Euclid, an expert on geometry, claimed that triangles have three sides.

Conclusion: Triangles do not have three sides.

It must be noted that there are rational grounds for doubting an expert—as discussed in the essay on argument from authority. When a person rationally applies the standards of assessing an alleged expert and decides that the expert lacks credibility, this would not be an error. But to reject a claim solely because of the source is always a fallacy (usually an ad hominem) and rejecting a claim because it was made by an expert would be doubly fallacious, if there were such a thing.

Since experts are generally more likely to be right than wrong, this sort of reasoning will tend to lead to accepting untrue claims. While this is a bad idea in normal times, it is even more dangerous during a pandemic. In the case of COVID-19, there are those who use this reasoning to reject the claims of medical experts. This can, obviously enough, lead to illness and death. Because the fallacy lacks all logical force, it derives its influence from psychological factors, and these are worth considering when trying to defend against and respond to this dangerous fallacy.

Our first step in understanding the driving forces behind this fallacy take us back to ancient Athens to visit our good dead friend Socrates. One of Socrates’ friends went to the oracle of Delphi and asked them who was the wisest of men. It was, of course, Socrates. While many would accept such praise, Socrates believed that the gods were wrong and set out to disprove them by finding someone wiser. He questioned the poets, the politicians, the craftspeople—anyone who would speak with him. He found that everyone believed they knew far more than they did—and the more ignorant a person, the more they believed they knew.

Reflecting on this, Socrates concluded that the gods were right: he was the wisest because he knew that he knew nothing, that his infinite ignorance eclipsed what little he knew. While some were grateful to Socrates, most were outraged at Socrates and saw to it that he was put on trial and sentenced to death. Sorry, spoilers.

While we now have smartphones, people have not changed since those times: most people believe they know far more than they do, and they resent anyone who would disagree. And resent most of all someone who reveals their ignorance. Technology has made this worse

—thanks to the “University of Google” and social media, people not only doubt the experts but regard themselves as equal to or better than them.

The fundamental lesson of philosophy provides the obvious defense against this arrogant ignorance: realizing, as Socrates did, that wisdom is recognizing that we know nothing. This is not to embrace empty skepticism in which everything is doubted, but to accept a healthy skepticism of the extent of our own knowledge and to develop a willingness to listen to those who have knowledge.

We can continue our philosophical adventure centuries past the death of Socrates by visiting our good dead friend John Locke. While Locke is best known for “life, liberty and property” he also wrote on enthusiasm. By enthusiasm he did not mean being really stoked about your sports team or getting free guacamole—he was concerned with the tendency people have to believe a claim because they strongly feel it to be true. While Locke was very concerned with this in the context of religion, he held to a very sensible general principle that one should believe in proportion to the evidence rather than in proportion to the strength of feeling.

While psychologists and cognitive scientists have examined the various cognitive biases that contribute to what Locke calls enthusiasm, his basic idea is still correct: believing based on strong feelings is not a rational way to form beliefs. True beliefs can be backed up with evidence and reason. The power of this enthusiasm leads people to believe based on the strength of their feelings and they will often be wrong—thus leading them to reject what experts claim when there is disagreement. They will feel that they are right and that their strong feeling counts more than expertise.

The defense against this is not, obviously, to become unfeeling. Rather it is to be aware that feelings are not evidence and to endeavor to proportion belief to the evidence, not the feeling. This is very difficult to do—it is hard to fight feelings. But rational decision making that can save your life and the lives of others requires this—especially now. How we feel about COVID, social distancing or alleged cures proves nothing. Only proof proves things.