John G. Messerly's Blog, page 44

September 10, 2020

Lars Tornstam on Gerotranscendence

Lars Tornstam (1943 – 2016)

My recent post, Summary of Maslow on Self-Transcendence, elicited many thoughtful comments. One reader, Dr. Janet Hively, suggested that self-transcendence is connected with aging, writing, “people gain experience and wisdom as they grow older, reaching the age for generativity toward the end of life.” She also suggested that I look into the theory of gerotranscendence, elucidated in detail by the Swedish sociologist Lars Tornstam in his 2005 book, Gerotranscendence: A Developmental Theory of Positive Aging[image error]. As Tornstam put it:

Gerotranscendence is the final stage in a natural process moving toward maturation and wisdom. The gerotranscendent individual experiences a new feeling of cosmic communion with the spirit of the universe, a redefinition of time, space, life and death, and a redefinition of self.1

Here is another definition:

The theory of gerotranscendence describes a … perspective shift from a more materialistic and rational view of life to a more transcendental [one] … leading to significant changes in the way of perceiving self, relationships with other people and life as a whole …2

According to Tornstam, growing older and “into old age has its very own meaning and character, distinct from young adulthood or middle age.” In other words, there is ongoing personality development into old age. Interviews with individuals between 52 and 97 years of age confirmed this idea and led to his theory of gerotranscendence. Gerotranscendent individuals are those who develop new understandings of: 1) the self; 2) relationships to others; and 3) the cosmic level of nature, time, and the universe. Specific changes that occur include:

Level of Self

A decreased obsession with one’s body

A decreased interest in material things

A decrease in self-centeredness

An increased desire to understand oneself

An increased desire for inner peace and meditation

An increased need for solitude

Level of Personal and Social Relationships

A decreased desire for prestige

A decreased desire for superfluous, superficial social interaction

A decreased interest in conforming to social roles

An increased concern for others

An increased need for solitude, or the company of only a few intimates

An increased selectivity in the choice of social and other activities

An increased spontaneity that moves beyond social norms

An increase in tolerance and broadmindness

An increased sense of life’s ambiguity

Cosmic Level

A decreased distinction between past and present

A decreased fear of death

An increased affinity with, and interest in, past and future generations

An increased acceptance of the mysteries of human life

An increased joy over small or insignificant things

An increased appreciation of nature

An increased feeling of communion with the universe and cosmic awareness

According to the theory of gerotranscendence, people should surrender their youthful identity in order to achieve true maturity and wisdom. This view of aging stands in contrast to the view that successful aging is a kind of perpetual youth where people try to remain active, productive, independent, healthy, wealthy and sociable. But an 80-year-old differs from their 50-year-old self, just as the latter did from their 30-year-old self. Your 80-year-old mother may not want to party, play golf, make money or be very much engaged, not because she’s sick or depressed, but because she now prefers painting, reading, writing, meditating, walking, gardening or listening to music. We are often so enamored with activity that we forget that Mom may enjoy sitting in her rocking chair sometimes. None of this implies that this is the only way to successfully age, just that it is a reasonable way.

[image error]

Now just growing older doesn’t mean that one will become gerotranscendent, although aging does bring existential questions about death and the meaning of life to the forefront. So how does one become a gerotranscendent? The process is mostly stimulated by experiencing hardships, challenges, transitions and the losses of living, combined with continual reflection about one’s life, the life of others, and universal life. Still there are a number of obstacles to becoming a gerotranscendent including:

job preoccupation (or ego differentiation): the inability to let go of your earlier careers. Gerotranscenders are able to transcend the way that their identity was tied to their previous work.

body preoccupation (or body transcendence): the inability to let go of obsessing about bodily ailments. Gerotranscenders care about their bodies, but transcend identifying with it.

ego preoccupation (or ego transcendence): inability to let go of obsessing about the ego. Gerotranscenders transcend the ego by accepting the inevitability of death, and by living more unselfishly.

Some of the weaknesses of the theory include the fact that gerotranscendence: 1) isn’t precisely defined; 2) is limited to old age when there are some younger persons who possess the above qualities; and 3) considers gerotranscendence from an individual perspective without much consideration of the social and biological factors that influence successful aging. It also seems to conflict with the fact that “the prevalence of depression in old age” is quite high.3

Still there is substantial evidence that gerotranscendence captures the essence of aging successfully. Much of this research is described in “Theory of Gerotranscendence: An Analysis,” by Rajani and Nawaid. Some of the highlights of this research show that those who have faced life crisis have higher levels of gerotranscendence, and that there is “a positive relationship between gerotranscendence and life satisfaction.” Furthermore, research has shown “a significant correlation between the cosmic transcendence and feeling of coherence and meaning of life. Transcendence in life promotes health, harmony, healing and meaningfulness in life of older adults. Studies have also attested the fact that people who find meaning in life tend to experience better physical health.”

Reflections – I like the gerotranscendent theory of aging. It reminds me somewhat of the idea of being “weened away from life” in Thorton Wilder’s marvelous play “Our Town.” It also brings to mind this profound statement about aging from the great philosopher Bertrand Russell in his essay,”How To Grow Old.”

The best way to overcome it [the fear of death]—so at least it seems to me—is to make your interests gradually wider and more impersonal, until bit by bit the walls of the ego recede, and your life becomes increasingly merged in the universal life. An individual human existence should be like a river: small at first, narrowly contained within its banks, and rushing passionately past rocks and over waterfalls. Gradually the river grows wider, the banks recede, the waters flow more quietly, and in the end, +without any visible break, they become merged in the sea, and painlessly lose their individual being. The man who, in old age, can see his life in this way, will not suffer from the fear of death, since the things he cares for will continue. And if, with the decay of vitality, weariness increases, the thought of rest will not be unwelcome. I should wish to die while still at work, knowing that others will carry on what I can no longer do and content in the thought that what was possible has been done.

So I do agree with Dr. Hively’s that there is a connection between age, and the wisdom to transcend the self and its concern with body, prestige, material possessions. Maslow’s self-transcendence is closely aligned with Tornstam’s gerotranscendence. This kind of wisdom and change of heart is hard to achieve without having lived and loved and suffered—the wisdom of the heart seems largely based upon time. This isn’t to say that older people are always wiser than younger people of course but, all things being equal, the achievement of wisdom is aided by time.

Yet, having said all this, I still believe that death itself is an evil that we should try to defeat. As I’ve written elsewhere, death should be optional. But for those of us who must age and die, Tornstam has shown us a noble and enlightening way to travel that road.

(I was led to Tornstam’s work when I encountered Maslow on self-transcendence.)

_______________________________________________________________________

1. “Transcendence in late life.” Generations, 23 (4), p. 11.

2. https://sv.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gerotra...

3. Rivard TM, Buchanan D. National Guidelines for Seniors’ Mental Health: The Assessment and Treatment of Depression. 2006.

I would like to sincerely thank Dr. Jan Hively for introducing me to Tornstam’s work.

(Note. This post first appeared on this blog on August 7, 2017.)

September 7, 2020

Types of Love

[image error]

I have discussed love in a number of previous posts: “On Love and Pain,” “Human Relationships on a Sliding Scale,”” There is no Afterlife,” “Romantic Love and the Idea of Settling,” “We Must Love One Another or Die,” “Is Love Stronger Than Death?” and “The Art of Loving.” But to best understand the concept of love we need to carefully define love.

Different Kinds of Love

The Greeks distinguished at least 6 different kinds of love:

1) Eros was the notion of sexual passion and desire but, unlike today, it was considered irrational and dangerous. It could drive you mad, cause you to lose control, and make you a slave to your desires. The Greeks advised caution before one gives in to these desires.

2) Philia denoted friendship which was thought more virtuous than sexual or erotic love. It refers to the affection between family members, colleagues, and other comrades. However, these persons are much closer to you than Facebook friends or Twitter followers.

3) Ludus defines a more playful love. This ranges from the playful affection of children all the way to the flirtation or the affection between casual lovers. Playing games, engaging in casual conversation, or flirting with friends are all forms of this playful love.

4) Pragma refers to the mature love of lifelong partners. After a lifetime of compromise, tolerance, and shared experiences a calm stability and security ensues. Commitment between partners is the key; they mutually support and respect each other.

5) Agape is a radical, selfless, non-exclusive love; it is altruism directed toward everyone (and perhaps to the environment too.) It is love extended without concern for reciprocity. Today we would call this charity; or what the Buddhists call loving-kindness.

6) Philautia is self-love. The Greeks recognized two forms. In its negative form philautia is the selfishness that wants pleasure, fame, and wealth beyond what one needs. Narcissus, who falls in love with his own reflection, exemplifies this kind of self-love. In its positive form philautia refers to a proper pride or self-love. We can only love others if we love ourselves; and the warm feelings we extend to others emanate from good feelings we have for ourselves. If you are self-loathing, you will have little love to give.1

These distinctions undermine the myth of romantic love so predominant in modern culture. People obsess about finding soul mates, that one special person who will fulfill all their needs—a perpetually erotic, friendly, playful, selfless, stable partner. In reality, no person fulfills all these needs. And the twentieth-century commodification of love renders the situation even worse. We buy love with engagement rings; market ourselves with clothes, body modifications, Facebook profiles, and on internet dating sites; and we look for the best object we can find in the market given an assessment of our trade value.

This is not to suggest that everything is wrong with the modern world or that the internet isn’t a good place to find a mate—it may be the best place. (Although I’m much too old to worry about it!) Rather I suggest that to be satisfied in love, as in life, one must cultivate multiple interests, strategies, and relationships. We may get the most stability from our spouse, but find playful times with our grandchildren or our golfing partners; we may find friendship with our philosophical comrades; and we might find an outlet for altruism in our charitable contributions or in productive work.

As for our most intimate relationships, we would do best to lower our expectations—again no one satisfies all our needs. As I said in my previous post, this is not the idealized love of Hollywood movies, but it is real love. No, you won’t have heart palpitations every time you see your beloved after 35 years, but you will feel the presence that accompanies a lifetime of shared love, a lifetime of struggling and fighting and working together. You will feel the continuity of knowing someone who knew you when you were young, middle age, and old, and they will feel the same. The accompanying serenity is peaceful and priceless. I hope everyone can experience this.

___________________________________________________________________________

1. Rousseau made a similar distinction between amour-propre and amour de soi. Amour de soi is a natural form of self-love; we naturally look after our own preservation and interests and there is nothing wrong with this. By contrast, amour-propre is a kind of self-love that may arise when we compare ourselves to others. In its corrupted form, it is a source of vice and misery, resulting in human beings basing their own self-worth on their feeling of superiority over others.

Note. This post first appeared on this blog on March 15, 2016.

September 3, 2020

The Case Against Hope

[image error]

Pandora trying to close the box that she had opened out of curiosity. At left, the evils of the world taunt her as they escape. The engraving is based on a painting by F. S. Church.

Hope is the worst of evils, for it prolongs the torment of men. ~ Friedrich Nietzsche

For the past few weeks, we investigated the concept of hope. In the process we have come to offer a spirited defense of hope and, to a lesser extent, optimism. I’d now like to “play the flip side,” as an old colleague used to say, and consider some critics of hope.

Kazantzakis’ Case Against Hope

I have previously expressed my affinity for the thought of the Greek novelist Nikos Kazantzakis (1883 – 1957). I have also discussed his case against hope in detail in, “Kazantzakis’ Epitaph: Rejecting Hope.” Here are a few highlights of his case against hope:

… leave the heart and the mind behind you, go forward … Free yourself from the simple complacency of the mind that thinks to put all things in order and hopes to subdue phenomena. Free yourself from the terror of the heart that seeks and hopes to find the essence of things. Conquer the last, the greatest temptation of all: Hope …

Why should we abandon hope according to Kazantzakis? Because we often lose hope and cease acting. Instead, we should seek and strive, even if our efforts are in vain. Don’t hope for good outcomes, or understanding, or meaning, he counsels, but ascend and move forward. We are tempted by hope, but the courageous live without it, carrying on in its absence. Kazantzakis describes his rejection of hope or optimism, in this passage from his autobiography, Report to Greco:

Nietzsche taught me to distrust every optimistic theory. I knew that [the human] heart has constant need of consolation, a need to which that super-shrewd sophist the mind is constantly ready to minister. I began to feel that every religion which promises to fulfill human desires is simply a refuge for the timid, and unworthy of a true man … We ought, therefore, to choose the most hopeless of world views, and if by chance we are deceiving ourselves and hope does exist, so much the better … in this way man’s soul will not be humiliated, and neither God nor the devil will ever be able to ridicule it by saying that it became intoxicated like a hashish-smoker and fashioned an imaginary paradise out of naiveté and cowardice—in order to cover the abyss. The faith most devoid of hope seemed to me not the truest, perhaps, but surely the most valorous. I considered the metaphysical hope an alluring bait which true men do not condescend to nibble …

Note – The hope that Kazantzakis rejects is metaphysical and forward-looking, and I too reject such hopes. And he wants us to act, which I argue is the essence of hope. Thus nothing he says here undermines the kind of hope I advocate.

Nietzsche’s Pessimism

There are many great pessimists in the Western philosophical tradition—Voltaire, Rousseau, Schopenhauer, and others—but let’s focus on Nietzsche. He associates weak pessimism with Eastern renunciation; strong pessimism with an Eastern notion of harmonizing contradictions; and Socratic optimism with Western philosophy’s emphasis on logic, beauty, goodness, and truth. Nietzsche’s pessimism refers to the fact that reality is cruel, irrational, and always changing; while optimism is the view that reality is orderly, intelligible, and open to betterment. Optimists mistakenly believe that they can overcome the abyss and make the world better by action, but Nietzsche wants us to see reality realistically and be pessimists.

Yet Nietzsche doesn’t want us to be weak pessimists like the Buddha, who advised us to eliminate desires, or like Schopenhauer, who believed that in resignation from striving we find freedom. Instead, Nietzsche wants us to be strong pessimists who affirm life rather than renounce it, who fill life with their enthusiasm, and who take pleasure in what is hard and terrible. Salvation and freedom come from accepting the contradictory and destructive nature of reality and responding with joyous affirmation.

In other words, Nietzsche’s response to the tragedy of life is neither resignation nor self-denial, but a life-affirming pessimism. He sees Socratic philosophy and most religion as an optimistic refuge for those who will not accept the tragic sense of life. But he also rejects Schopenhauer’s pessimism and nihilism. Nietzsche’s pessimism says yes to life. He counsels us to embrace life and suffer joyfully.

Note – Nietzsche’s thoughts are consistent with Kazantzakis’ and my own. He rejects both resignation and a hope which includes expectations. Instead, he calls us to action, as do I. Thus nothing he says here undermines the kind of hope I advocate.

Stoicism

While Michael and Caldwell used Stoicism to defend caring without lamentation, a view that they argue is consistent with optimism, most interpret the Stoics differently. For example, consider how the Stoics address the issue of anxiety. When you are anxious, most people try to cheer you up by telling you things will be ok. But the Stoics hate consolation meant to give hope—the opiate of the emotions. They believe that we must eliminate hope to find inner peace because hoping for the best makes things worse, especially because your hopes are inevitably dashed. Instead, they advise that we tell ourselves that things will get worse because, when we envision the worst, we will discover that we can manage it. And if things get too bad, the Stoics remind us that we can always commit suicide.

Or consider the Stoics on anger. Anger comes when misplaced hopes smash into unforeseen reality. We get mad, not at every bad thing, but at bad, unexpected things. So we should expect bad things—not hope they don’t occur—and then we won’t be angry when things go wrong. Wisdom is reaching a state where no expected or unexpected tragedy disturbs our inner peace, so again we do best without hope. Still, this doesn’t imply total resignation to our fate; there are still some things we might be able to change.

Finally, to better understand the Stoics rejection of hope, let’s listen to Seneca:

[t]hey [hope and fear] are bound up with one another, unconnected as they may seem. Widely different though they are, the two of them march in unison like a prisoner and the escort he is handcuffed to. Fear keeps pace with hope. Nor does their so moving together surprise me; both belong to a mind in suspense, to a mind in a state of anxiety through looking into the future. Both are mainly due to projecting our thoughts far ahead of us instead of adapting ourselves to the present.

Note – The Stoics reject hope as expectation, lamentation, and consolation; not hope as action. Thus nothing they say here undermines the kind of hope I advocate.

Simon Critchley’s Case Against Hope

Simon Critchley, chair and professor of philosophy at The New School for Social Research in New York City, recently penned this piece in the New York Times: “Abandon (Nearly) All Hope.” In it, he defends a theme similar to the one he argued for in his book, Very Little … Almost Nothing … [image error](I reviewed the book on this blog.) Critchley regards hope as another redemptive narrative, or perhaps as an element in all redemptive narratives. Instead of succumbing to the temptation of hope, he suggests we be realistic and brave—a view reminiscent of the one held by Nietzsche and Kazantzakis.

Critchley begins by asking: “Is it [hope] not rather a form of moral cowardice that allows us to escape from reality and prolong human suffering?” If hope is escapism or wishful thinking, if it is blind to reality or contrary to all evidence, then it is a form of moral cowardice?

To elucidate these ideas Critchley recalls Thucydides’ story of the Greeks’ ultimatum to the Melians—surrender or die. Rather than submit, the Melians hoped for a reprieve from their allies or their gods, despite the evidence that such hopes were misplaced. The reprieve never comes, and all the Melians were either killed or enslaved. In such situations, Critchley counsels, not hope, but courageous realism. False hopes will seal our doom as they did the Milians. From such considerations, Critchley concludes: “You can have all kinds of reasonable hopes … But unless those hopes are realistic we will end up in a blindly hopeful (and therefore hopeless) idealism … Often, by clinging to hope, we make the suffering worse.”

Note – I too reject false hopes, but Critchley admits you can have reasonable hopes. Thus nothing he says here undermines the kind of hope I advocate.

Oliver Burkeman on Hope as Deception

In a recent column in the Guardian, Oliver Burkeman argued that what is often called hope is really deception—hoping for things that are virtually impossible. For example, hoping that one wins the lottery, or that the victims of an accident have survived when their deaths are near certainties.

By contrast, letting go of hope often sets us free. To support this claim he refers to “recent research … suggesting that hope makes people feel worse.” For instance: the unemployed who hope to find work are less happy than those who accept they won’t work again; those in the state of hoping for a miraculous cure for a terminal disease are less happy than those who accept that they will die; and people more often act for change when they stop hoping that others will do so. Perhaps there is something about giving up hope and accepting a reality that is comforting.

Note – I too reject hope with expectations. Thus nothing he says here undermines the kind of hope I advocate.

My Reflections

The common theme in these critiques is the futility of false hopes, which lead inevitably to disappointment. I agree. If I hope to become the world’s most famous author or greatest tennis player, my expectations are bound to be dashed. Silly to hope for such things. Much better to hope that I enjoy writing and tennis despite my shortcomings in both.

For instance, when confronted by the reality of the concentration camps, Viktor Frankl didn’t hope to dig his way out of his prison. That wasn’t impossible. Instead, he hoped that the war would end and he might be freed. That was realistic. Thus the difference between false and realistic hope. The former is delusional, the latter worthwhile. Sometimes only fools keep believing; sometimes you should stop believing. False hopes prolong misery.

But I want to know if I’m justified in hoping (without expectation) that life has meaning or that truth, beauty and goodness matter. And I think I am. Why? Because regarding questions about the ultimate purpose of ourselves and the cosmos, we just don’t know enough to say that hope is unjustified. It is reasonable to think that life might have meaning, it is not impossible that it does. Thus this is not a false hope, even if the object of my hopes may not be fulfilled.

Thus we can legitimately hope that life is meaningful without being moral cowards. Of course, life may be pointless and meaningless. We just don’t know. But if we bravely accept that we just don’t know whether life is meaningful or not, then we live with moral and intellectual integrity. And there is no more honest or better way to live.

____________________________________________________________________

Note. This post first appeared on this blog on March 14, 2017.

August 31, 2020

Marcel on Creativity and Hope

[image error]

There are two ideas in Marcel’s philosophy, in addition to those considered in my last post, that I would like to discuss briefly—the importance of creative fidelity and of hope.

Creative Fidelity – For Marcel to exist existentially, as opposed to just functionally, one must be creative. As he argues: “A really alive person is not merely someone who has a taste for life, but somebody who spreads that taste, showering it, as it were, around him; and a person who is really alive in this way has, quite apart from any tangible achievements of [theirs], something essentially creative about [them] …”1

What Marcel calls “creative fidelity” involves giving a part of ourselves to others, which we do by sharing love and friendship, as well as through the creative, performing, and fine arts. Creative fidelity binds us to others, recognizing their subjectivity while expressing our own. Creative fidelity is the tenacious, constant desire to elaborate who we are—to have a greater sense of being, we need creative fidelity. We become creatively faithful when we bridge the gap between ourselves and others when we make ourselves present to them.

Hope – Hope guarantees fidelity by defeating despair—it gives us the strength to continually create—but it is not the same as optimism. Optimism, like fear or desire, imagines or anticipates a favorable or unfavorable outcome. We “desire that x” or “fear that x.” Hope is different. We don’t hope that x, we simply hope. Hope rejects the current situation as final, but it doesn’t anticipate a specific result that will deliver us from our plight. Hope transcends anticipating a specific form of our deliverance—it is a vague hoping. My desires can be thwarted, but if I maintain hope no outcome will shake me from hoping. It is the very non-specificity of hoping that gives hope its power.

Yet hope is not passive; it is not resignation or acceptance. Instead, “Hope consists in asserting that there is at the heart of being, beyond all data, beyond all inventories and all calculations, a mysterious principle which is in connivance with me.”2 This implies that hope is an active willing, not a surrender. And hope is a willing, a wanting, not only for ourselves but for others. “There can be no hope that does not constitute itself through a we and for a we. I would be tempted to say that all hope is at the bottom choral.”3 For genuine hope we cannot depend completely upon ourselves—it derives from humility, not pride.

This example points to the dialectical engagement of despair and hope—where there is hope there is always the possibility of despair, and only where there is the possibility of despair can we respond with hope. Despair, says Marcel, is equivalent to saying that there is nothing in the whole of reality to which I can extend credit, nothing worthwhile. “Despair is possible in any form, at any moment and to any degree, and this betrayal may seem to be counseled, if not forced upon us, by the very structure of the world we live in” (Marcel 1995, p. 26). Hope is the affirmation that is the response to this denial. Where despair denies that anything, in reality, is worthy of credit, hope affirms that reality will ultimately prove worthy of an infinite credit, the complete engagement, and disposal of myself.

Thus there is a dialectical relationship between hope and despair. We can respond to despair with hope, and within hope, there is always the possibility of despair. To despair is to say there is nothing worthwhile in the world: “Despair is possible in any form, at any moment and to any degree, and this betrayal may seem to be counseled, if not forced upon us, by the very structure of the world we live in.”4 Hope is an affirmative response to despair. Hope affirms that your creative fidelity, your work, your concern, your love, and your life, all ultimately matter.

Reflections – I like the idea of creative fidelity. It is reminiscent of Marx’s idea of non-alienated labor, labor that elaborates who we are, connecting us with ourselves, nature, and others. The world would be better if culture encouraged us to be creatively faithful.

I also like the idea of hope, but I think the distinction between optimism, hope, wishes, and longings needs to be more carefully drawn. The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language defines optimism as: “A tendency to expect the best possible outcome or dwell on the most hopeful aspects of a situation.” In neither of these senses am I or is Marcel an optimist. We do not expect our most fervent wishes to come true, nor do we dwell on the most hopeful possibilities. The same source defines hope similarly: “To wish for something with expectation of its fulfillment. To look forward to with confidence or expectation.” In neither of these senses do I or Marcel have hope, because hope thus defined anticipates or expects an outcome.

The sense of hope that both Marcel and I believe in is the verb form of hope—hoping that something happens or becomes the case—which is essentially the same as wishing or longing for something. We hope, wish, or long for some vaguely defined outcome which we do not expect to be fulfilled. For example, we may wish or hope that life is meaningful. But to wish or hope this does not imply that we believe, have faith in, anticipate, or expect that life is meaningful—we are just hoping. Furthermore, our wishes, hopes, and longings exist in the realm of emotions and are thereby immune from intellectual criticism. After all, there is nothing irrational about hoping we win a lottery. We may know the chances of winning are remote, but as long as it’s possible to win, there is nothing wrong with wishing that we win. Of course, it’s stupid to think that we’ll win a typical lottery or to plan our lives as if we’ll win, but surely it is permissible to wish or hope for the winning numbers.

Finally, I will say this about hope, and I think Marcel would agree. Hope helps us to brave the struggle of life while keeping alive the possibility that we will create a better and more meaningful reality. In this sense hope is an attitude we have in the present that motivates us to act; it does not imply passivity or resignation. Hope is most precious.

(Since the above publication, I have further explored this issue in, “A Defense of Hope.”)

__________________________________________________________________________

1. Marcel, Gabriel. The Mystery of Being, Volume I. (Chicago: Charles Regnery Co, 1951) 139.

2. The Philosophy of Existentialism. Translated by Manya Harari. New York: Carol Publishing Group, 1995) 28.

3. Tragic Wisdom and Beyond. Translated by Stephen Jolin and Peter McCormick. Publication of the Northwestern University Studies in Phenomenology and Existential Philosophy, ed. John Wild. (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1973) 143.

4. The Philosophy of Existentialism. Translated by Manya Harari. New York: Carol Publishing Group, 1995) 26.

(Note. This post first appeared on this blog on April 16, 2014.)

August 27, 2020

Marcel on the broken world, problems, and mysteries

[image error]

Gabriel Marcel (1889-1973), who was born and died in Paris, was one of the leading Christian existentialists of the twentieth century. Two of his ideas that I find fascinating are his notion of the broken world, and the distinction between a problem and a mystery.

The Broken World – According to Marcel we live in a “broken world,” where “ontological exigence” is ignored or silenced. What he means is that exigencies, crises, difficulties, and pressures plague our being. This doesn’t imply that the world was once intact, rather that it is broken in essence—both in its past and present. In the here and now, our being is characterized by a refusal to reflect, imagine and wonder, which leads us to deny both the tragic and the transcendent. Marcel believed this is primarily due to the functions we play in modernity—functions that reduce us to automatons who lose a sense of wonder about being.

This ontological exigence, this desire of being for transcendence, meaning, coherence and truth, derives from the sense that something is amiss or lacking in the world. Marcel claims this longing is not mere wishing, but an urge or appeal that springs forth from our very nature. Without this sense of longing for transcendent meaning, one doesn’t notice that the world is broken. In this sense exigence is a good thing.

Commentary – I do think we live in a broken world; there is something deeply wrong with being. But I think Marcel’s mistaken when he says that we cannot live well without an appeal to transcendence. For Marcel transcendence is beyond us, and experiencing it involves “a straining of oneself towards something, as when, for instance, during the night we attempt to get a distinct perception of some far-off noise.”1 I assume this noise is Marcel’s God. As my readers know I acknowledge the longing, but doubt the existence of the object of Marcel’s longing. Still, the object of Marcel’s longing is amorphous, so Marcel is a mystic. I too can say that reality is mysterious.

Problems and Mystery – The broken world contains multiple problems which are capable of solutions. With data and technology we can solve problems. But we do not completely participate with a problem as a unique individual. We could substitute one scientist for another and the problem wouldn’t change—it exists independently of the scientist. And solutions to problems become common knowledge which can be rediscovered by anyone.

But we are intimately involved in a mystery. It is a sphere in which the distinction between what is inside and outside of me loses significance. When dealing with mysteries subjectivity matter, a mystery is one’s own. Moreover, mysteries can’t be solved; they are meta-problematic. (Hence the well-known aphorism attributed variously to Marcel and others: “Life is not a problem to be solved but a mystery to be lived.”) Mysteries are ineffable, incommunicable, and yet our subjectivity is built upon participating in them. I can have a problem—I can possess it—but essentially I am a mystery, for my mysteries involve my being. Ultimately, to truly confront mystery according to Marcel, one must open themselves up to the avenues designed for this purpose—religion, art, and metaphysics.

Commentary – There are some scientific problems we have solved—how the species evolved—and there are unsolved problems—how to reconcile relativity and quantum theories. Whether the unsolved problems are different from unsolved mysteries is debatable. And whether there are some essentially unsolvable, problems or mysteries—incapable of being understood in principle—raises deep issues in philosophy of language and epistemology. Still, I’m not sure if the problem and mystery distinction holds.

But whether we call them problems or mysteries there is much that is unknown and perhaps unknowable. I agree then that there are mysteries, but I’m not sure what to make of it when mystics talk of them. Perhaps mystics should heed Wittgenstein’s advice: Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” So if we do talk about mystery, we would do well not take our musings too seriously.

And yet there is something so compelling about a mystery …[image error]

__________________________________________________________________________

1. 1951a, The Mystery of Being, vol.1, Reflection and Mystery. Translated by G. S. Fraser. London: The Harvill Press.

(Note. This post first appeared on this blog on April 15, 2014.)

August 24, 2020

Gibran on Loneliness

[image error]

When I was about 18 years old I read the following words by the Lebanese artist, poet, and author Kahlil Gibran in a short collection of his writing entitled The Voice of the Master.[image error]

Life is an island in an ocean of loneliness, an island whose rocks are hopes, whose trees are dreams, whose flowers are solitude, and whose brooks are thirst.

Your life is an island separate from all the other islands and regions. No matter how many are the ships that leave your shores for other climes, no matter how many are the fleets that touch your coast, you remain a solitary island, suffering pangs of loneliness and yearning for happiness. You are unknown to others and far removed from their sympathy and understanding.

A few paragraphs later Gibran concludes that solitude is the price we pay for being unique individuals. In his view, we could completely know another, and thus escape our solitude, only if we were identical with them. I’m not sure that conclusion follows but I do think he’s right that we are, at the deepest level, alone.

We can ameliorate this loneliness by sympathizing with and loving others, but we never clearly see the world from their point of view nor they from ours. I’ve had good friends, loving parents and children, but they don’t know me nor do I know them completely. Even my wife and I, loving companions for almost forty years, remain partly mysterious to each other.

We might even say that we are strangers to ourselves too. But then the self isn’t alone so much as illusory. For who is this me that doesn’t know myself? Is that some other me? And is there another me that doesn’t that me? Such questions can be asked ad infinitum.

This is the flip side of saying that I do know myself. But who is this me that knows myself? Is that some other me? And is there is another me that knows that me? Again we confront an infinite regress.

In the end, I think we are both opaque and transparent to ourselves and to others. I think that’s because we are, simultaneously, both the same and different as everyone else, although I realize these statements are paradoxical. In the end, we just know so little about life. We live, not only alone but largely in the dark. But by remaining optimistic against a background of loneliness and nihilism we are ennobled. We can shake our fist indignantly at life and laugh at it simultaneously. ______________________________________________________________________

Personal Note – In one of the very first philosophy classes I took as an undergrad the Professor told us that this would be serious philosophy, not feel-good stuff like … Gibran. Wow was I disheartened. I was only 18 and proud that I had read Gibran. Of course, I now know what the professor meant—good analysis is necessary for good philosophy and Gibran’s poetry was hardly analytical. But sometimes poetic language sears an idea into the mind better than analytical prose. And that’s why I’ve always remembered those words. “Life is an island in an ocean of loneliness.” A beautiful image of a profound insight.

___________________________________________________________________________

Note. This post first appeared on this blog on April 1, 2018.

Gibran on Lonliness

[image error]

When I was about 18 years old I read the following words by the Lebanese artist, poet, and author Kahlil Gibran in a short collection of his writing entitled The Voice of the Master.[image error]

Life is an island in an ocean of loneliness, an island whose rocks are hopes, whose trees are dreams, whose flowers are solitude, and whose brooks are thirst.

Your life is an island separate from all the other islands and regions. No matter how many are the ships that leave your shores for other climes, no matter how many are the fleets that touch your coast, you remain a solitary island, suffering pangs of loneliness and yearning for happiness. You are unknown to others and far removed from their sympathy and understanding.

A few paragraphs later Gibran concludes that solitude is the price we pay for being unique individuals. In his view, we could completely know another, and thus escape our solitude, only if we were identical with them. I’m not sure that conclusion follows but I do think he’s right that we are, at the deepest level, alone.

We can ameliorate this loneliness by sympathizing with and loving others, but we never clearly see the world from their point of view nor they from ours. I’ve had good friends, loving parents and children, but they don’t know me nor do I know them completely. Even my wife and I, loving companions for almost forty years, remain partly mysterious to each other.

We might even say that we are strangers to ourselves too. But then the self isn’t alone so much as illusory. For who is this me that doesn’t know myself? Is that some other me? And is there another me that doesn’t that me? Such questions can be asked ad infinitum.

This is the flip side of saying that I do know myself. But who is this me that knows myself? Is that some other me? And is there is another me that knows that me? Again we confront an infinite regress.

In the end, I think we are both opaque and transparent to ourselves and to others. I think that’s because we are, simultaneously, both the same and different as everyone else, although I realize these statements are paradoxical. In the end, we just know so little about life. We live, not only alone but largely in the dark. But by remaining optimistic against a background of loneliness and nihilism we are ennobled. We can shake our fist indignantly at life and laugh at it simultaneously. ______________________________________________________________________

Personal Note – In one of the very first philosophy classes I took as an undergrad the Professor told us that this would be serious philosophy, not feel-good stuff like … Gibran. Wow was I disheartened. I was only 18 and proud that I had read Gibran. Of course, I now know what the professor meant—good analysis is necessary for good philosophy and Gibran’s poetry was hardly analytical. But sometimes poetic language sears an idea into the mind better than analytical prose. And that’s why I’ve always remembered those words. “Life is an island in an ocean of loneliness.” A beautiful image of a profound insight.

___________________________________________________________________________

Note. This post first appeared on this blog on April 1, 2018.

August 20, 2020

A Monopoly on Truth

Truth, holding a mirror and a serpent (1896). Olin Levi Warner, Library of Congress

Truth, holding a mirror and a serpent (1896). Olin Levi Warner, Library of Congress

As a follow-up to my recent post about truth, I would like to clarify what I see as the grave danger of being certain that one possesses the truth. As for truths in the natural sciences our concerns are irrelevant. Science by its nature is provisional; it is always open to contrary evidence and willing to adjust its views based on new evidence. Thus arrogant dogmatism is virtually impossible given the scientific method. The attitude of searching for truth and accepting provisionally what the evidence reveals prevents the kind of absolute certainty which is our main concern.

However, when humans believe strongly in areas where truth is difficult or perhaps impossible to attain, or where truth might not even exist, the situation is dire. Unlike in science, where the evidence constrains our thinking, in religion, for example, one can believe virtually anything. Moreover, these beliefs are often held with great fervency. It takes no willpower to believe in gravity or evolution—because the evidence overwhelms an impartial viewer—whereas in religion it often takes much faith. If we combine fervency of belief with strong faith we have a potent mix. If we feel strongly and we reject anything that will contradict our beliefs, naturally we may soon regard our beliefs as infallible. Crusades, inquisitions, persecution, and religious wars are the natural outgrowth of such attitudes. The great American philosopher John Dewey reflected on our concerns:

If I have said anything about religions and religion that seems harsh, I have said those things because of a firm belief that the claim on the part of religions to possess a monopoly of ideals and of the supernatural means by which alone, it is alleged, they can be furthered, stands in the way of the realization of distinctively religious values inherent in natural experience…. The opposition between religious values as I conceive them and religions is not to be abridged. Just because the release of these values is so important, their identification with the creeds and cults of religions must be dissolved.

The contemporary American philosopher Simon Critchley also captured our revulsion at arrogant dogmatism in a recent column in the New York Times entitled: “The Dangers of Certainty: A Lesson From Auschwitz.” Critchley advocates tolerance regarding our assessment of other persons; thereby rejecting the certainty that leads to arrogance, intolerance, and dogmatism.

The play of tolerance opposes the principle of monstrous certainty that is endemic to fascism and, sadly, not just fascism but all the various faces of fundamentalism. When we think we have certainty, when we aspire to the knowledge of the gods, then Auschwitz can happen and can repeat itself. Arguably, it has repeated itself in the genocidal certainties of past decades. … We always have to acknowledge that we might be mistaken. When we forget that, then we forget ourselves and the worst can happen.

Critchley also includes a moving video excerpt from Dr. Jacob Bronowski, a British mathematician and polymath. In the old video Bronowski visits Auschwitz, where he reflects on the horrors that follow when people believe themselves infallible. The video serves as a testimony to remind all of us of our fallibility.

Note. This post first appeared on this blog on February 5, 2014.

August 17, 2020

Philosophy, Science, and Religion

[image error]

In order to more clearly conceptualize Western philosophy’s territory, let’s consider it in relation to two other powerful cultural forces with which it’s intertwined: religion and science. We may (roughly) characterize the contrast between philosophy and religion as follows: philosophy relies on reason, evidence, and experience for its truths; religion depends on faith, authority, grace and revelation for truth. Of course, any philosophical position probably contains some element of faith, inasmuch as reasoning rarely gives conclusive proof; and religious beliefs often contain some rational support, since few religious persons rely completely on faith.

The problem of the demarcation between the two is made more difficult by the fact that different philosophies and religions—and philosophers and religious persons within similar traditions—place dissimilar emphasis on the role of rational argument. For example, Eastern religions traditionally place less emphasis on the role of rational arguments than do Western religions, and in the east philosophy and religion are virtually indistinguishable. In addition, individuals in a given tradition differ in the emphasis they place on the relative importance of reason and faith. So the difference between philosophy and religion is one of emphasis and degree.

Still, we reiterate what we said above: religion is that part of the human experience whose beliefs and practices rely significantly on faith, grace, authority, or revelation. Philosophy gives little if any, place to these parts of human experience. While religion generally stresses faith and trust, philosophy honors reason and doubt.

Distinguishing philosophy from science is equally difficult because many of the questions vital to philosophers—like the cause and origin of the universe or a conception of human nature—increasingly have been taken over by cosmologists, astrophysicists, and biologists. Perhaps methodology best distinguishes the two, since philosophy relies on argument and analysis rather than empirical observation and experiment. In this way, philosophy resembles theoretical mathematics more than the natural sciences. Still, philosophers utilize evidence derived from the sciences to reformulate their theories.

Remember also that, until the nineteenth century, virtually every prominent philosopher in the history of western civilization was either a scientist or mathematician. In general, we contend that science explores areas where a generally accepted body of information and methodology directs research involved with unanswered scientific questions. Philosophers explore philosophical questions without a generally accepted body of information

Philosophical analysis also ponders the future relationship between these domains. Since the seventeenth-century scientific revolution, science has increasingly expropriated territory once the exclusive province of both philosophy and religion. Will the relentless march of science continue to fill the gaps in human knowledge, leaving less room for the poetic, the mystical, the religious, and the philosophical? Will religion and philosophy be archaic, antiquated, obsolete, and outdated? Or will there always be questions of meaning and purposes that can never be grasped by science?

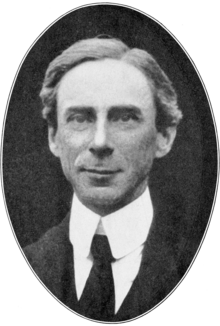

Bertrand Russell (1872-1970), one of the twentieth century’s greatest philosophers, elucidated the relationship between these three domains like this: “All definite knowledge … belongs to science; all dogma as to what surpasses definite knowledge belongs to theology. But between theology and science there is a no man’s land, exposed to attack from both sides; this no man’s land is philosophy.”

_______________________________________________________________________

Note. This post first appeared on this blog on March 22, 2016.

August 13, 2020

“A Free Man’s Worship”

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (1872 – 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, historian, atheist, and social critic. He is, along with his protégé Ludwig Wittgenstein, one of the founders of analytic philosophy and widely held to be one of the 20th century’s most important logicians. He co-authored, with A. N. Whitehead, Principia Mathematica, an attempt to ground mathematics in logic. His writings were voluminous and covered a vast range of topics including politics, ethics, and religion. Russell was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1950 “in recognition of his varied and significant writings in which he champions humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought.” Russell is thought by many to be the greatest philosopher of the 20th century.

Russell’s view of the meaning of life is set forth most clearly in his 1903 essay: “A Free Man’s Worship.” It is truly one of the classics of the meaning of life literature. It begins with an imaginary conversation about the history of creation between Mephistopheles, the devil, and Dr. Faustus, a man who sells his soul to the devil in return for power and wealth. In Russell’s story, God had grown weary of the praise of the angels and thought it might be more amusing to gain the praise of beings that suffered. Hence God created the world.

Russell describes the epic cosmic drama, and how after eons of time the earth and human beings came to be. Humans, seeing how fleeting and painful life is before their inevitable death, vowed that there must be some purpose outside of this world. And though following their instincts led to sin and the need for God’s forgiveness, humans believed that God had a good plan leading to a harmonious ending for humankind. God, convinced of human gratitude for the suffering he had caused, destroyed man and all creation.

Russell argues that this not-so-uplifting story is consistent with the world-view of modern science. To elaborate he penned some of the most pessimistic and often quoted lines in the history of twentieth-century philosophy:

That man is the product of causes which had no prevision of the end they were achieving; that his origin, his growth, his hopes and fears, his loves and his beliefs, are but the outcome of accidental collocations of atoms; that no fire, no heroism, no intensity of thought and feeling, can preserve an individual life beyond the grave; that all the labors of the ages, all the devotion, all the inspiration, all the noonday brightness of human genius, are destined to extinction in the vast death of the solar system, and that the whole temple of Man’s achievement must inevitably be buried beneath the debris of a universe in ruins–all these things, if not quite beyond dispute, are yet so nearly certain, that no philosophy which rejects them can hope to stand. Only within the scaffolding of these truths, only on the firm foundation of unyielding despair, can the soul’s habitation henceforth be safely built.

Still, despite the ultimate triumph of vast universal forces, humans are superior to this unconscious power in important ways—they are free and self-aware. This is the source of their value. But most humans do not recognize this, instead choosing to placate and appease the gods in hope of reprieve from everlasting torment. They refuse to believe that their gods do not deserve praise, worshiping them despite the pain the gods inflict. Ultimately they fear the power of the gods, but such power is not a reason for respect and worship. For respect to be justified, creation must really be good. But the reality of the world belies this claim; the world is not good and submitting to its blind power enslaves and ultimately kills us.

Instead, let us courageously admit that the world is bad, Russell says, but nevertheless love truth, goodness, beauty, and perfection, despite the fact that the universe will destroy such things. By rejecting this universal power and the death it brings, we find our true freedom. While our lives will be taken from us by the universe, our thoughts can be free in the face of this power. In this way, we maintain our dignity.

However, we should not respond to the disparity between the facts of the world and its ideal form with indignation, for this binds our thoughts to the evil of the universe. Rather we ought to follow the Stoics, resigned to the fact that life does not give us all we want. By renouncing desires we achieve resignation, while the freedom of our thoughts can still create art, philosophy, and beauty. But even these goods ought not to be desired too ardently, or we will remain indignant; rather we must be resigned to accept that our free thoughts are all that life affords in a hostile universe. We must be resigned to the existence of evil, and to the fact that death, pain, and suffering will take everything from us. The courageous bear their suffering nobly and without regret; their submission to power an expression of their wisdom.

Still, we need not be entirely passive in our renunciation. We can actively create music, art, poetry, and philosophy, thereby incorporating the ephemeral beauty of this world into our hearts, achieving the most that humans can achieve. Yet such achievements are difficult, for we must first encounter despair and dashed hopes so that we may be somewhat freed from the Fate that will engulf us all—freed by the wisdom, insight, joy, and tenderness that our encounter with darkness brings. As Russell puts it:

When, without the bitterness of impotent rebellion, we have learnt both to resign ourselves to the outward rule of Fate and to recognize that the non-human world is unworthy of our worship, it becomes possible at last so to transform and refashion the unconscious universe, so to transmute it in the crucible of imagination, that a new image of shining gold replaces the old idol of clay.

In our minds, we can create beauty in the face of Fate and tragedy, and thereby thwart nature to some extent. Life is tragedy, but we need not give in; instead, we can find the “beauty of tragedy” and embrace it. In death and pain, there is sanctity, awe, and a feeling of the sublime. Such feelings allow us to reject petty and trivial desires, and to transcend the loneliness and futility we experience when confronted with vast forces which are both indifferent and inimical to us. To take the tragedy of life into one’s heart, and respond with renunciation, wisdom, and charity, is the ultimate victory for man: “To abandon the struggle for private happiness, to expel all eagerness of temporary desire, to burn with passion for eternal things—this is emancipation, and this is the free man’s worship.” For Russell the contemplation of Fate and tragedy are the way we subdue them.

As for our fellow companions, all we can do is to ease their sorrow and sufferings, and not add to the misery that Fate and death will bring. In this, we can take pride. Nonetheless, the universe continues its inevitable march toward its own death, and humans are condemned to lose everything. All we can do is to cherish those brief moments when thought and love ennoble us, and reject the cowardly terror of less virtuous persons who worship Fate. We must ignore the tyranny of reality that continually undermines all of our hopes and aspirations. As Russell so eloquently puts it:

Brief and powerless is man’s life; on him and all his race the slow, sure doom falls pitiless and dark. Blind to good and evil, reckless of destruction, omnipotent matter rolls on its relentless way; for man, condemned today to lose his dearest, tomorrow himself to pass through the gate of darkness, it remains only to cherish … the lofty thoughts that ennoble his little day; disdaining the coward terrors of the slave of Fate, to worship at the shrine that his own hands have built; undismayed by the empire of chance, to preserve a mind free from the wanton tyranny that rules his outward life; proudly defiant of the irresistible forces that tolerate, for a moment, his knowledge and condemnation, to sustain alone, a weary but unyielding Atlas, the world that his own ideals have fashioned despite the trampling march of unconscious power.

Summary – There is no objective meaning in life. We should be resigned to this, but strive nonetheless to actively create beauty, truth, and perfection. In this way, we achieve some freedom from the eternal forces that will destroy us.

__________________________________________________________________

Russell, “A Free Man’s Worship,” 61.

(Note. This post originally appeared on this blog on December 12, 2015.)