John G. Messerly's Blog, page 40

January 11, 2021

Cosmological Immortality

[image error]

Clément Vidal‘s essay, “Cosmological Immortality: How to Eliminate Aging on a Universal Scale” discusses various scenarios of cosmic immortality.1 Vidal says that we might worry about the far future because, for example, we may come to live extremely long lifespans or we simply care about future beings who will live there. With such concerns in mind, he considers two religiously inspired and two scientifically inspired narratives of cosmic immortality.2

The Cosmological Soul – If the many-worlds interpretation of quantum physics is correct, then “our universe keeps branching into parallel universes.” Of course, we know nothing of such universes. Still, believing in”parallel universes could be interpreted in a similar way as the belief that the soul can separate from the body and survive after physical death.” The problem is that this interpretation of quantum mechanics is controversial and also it also doesn’t tell us if those parallel universes would be desirable.

Cosmological Resurrection – Cosmological models that imply a kind of resurrection including cyclical models, the phoenix universe, cosmological natural selection, the chaotic inflation scenario, the ekpyrotic model, or conformal cyclical cosmology. In these models, the cycle goes on, even if each particular universe doesn’t. None of these scenarios necessitate intelligence “but each particular universe could continue to form energy gradients and be able to sustain life.”

Cosmological Survival – Vidal claims that “as long as we can find free energy in the universe, we can hope to live forever.” Turning first to the sun, there have been “proposals to rejuvenate the Sun” in order to radically extend its lifespan. The idea of galactic rejuvenation is even more speculative. However, “the death of stars via supernovae replenish the interstellar medium and in turn allow the formation of new stars.” Perhaps we could someday manage the galaxy like an ecosystem.

It is hard to conceive of universal rejuvenation if for no other reason that even at the speed of light we can’t travel fast enough to reach many of the innumerable receding galaxies. Nonetheless, even as the universe continues to evolve towards its demise there might still be ways to live forever.

The answer is hibernation, and the scenario was articulated in a landmark article about the future of civilization by Dyson.3 Dyson shows that even assuming

a finite supply of energy, it would be possible for a civilization to live forever. An advanced civilization would hibernate longer and longer and thus use less and less energy. Despite a finite energy source, by hibernating longer and longer, and thus using less and less energy, a civilization would be able, in the limit, to live for as long as it wants in its subjective time. Of course, ‘‘life’’ is defined here not in terms of DNA and biochemistry, but as a more general information processing capability. However, this scenario does not work if the universe continues its accelerated expansion.”

Another idea that might lead to intelligence enduring forever is reversible computation.

Landauer4 proved the theoretical possibility of logic gates that consume no energy. Given a computer built out of such gates, a possible solution to the problem of an ever-expanding and slowly dying universe would be to simulate a new universe on a collection of matter that would forever float into emptier and emptier space.

However, most physicists have rejected this idea arguing that ‘‘no finite system can perform an infinite number of computations with finite energy if it is to host evolved information processing.”

Cosmological Legacy – The disposable soma theory says that “it is more efficient to invest energy in reproduction than in indefinite upkeep of the organism. Once the best chances for reproduction are used, thus ensuring the survival of the almost immortal genes (germline), the mortal body (soma) can be disposed of.” Some futurists speculate

that this theory may also apply to the universe. The soma is analogous to the constituents of the universe, with its mortal galaxies, stars, and planets, while the germline is analogous to free parameters that determine immortal physical laws. If we take seriously this fundamental trade-off in energy expenditure between soma and germline, the death of the ‘‘universe’s soma’’ may indeed be inevitable. But its germline, its most delicate physical structure, may be saved if universes are replicable.

Another idea is that future super-intelligent civilizations will engage in cosmological artificial selection.

The artificial selection of universes would be made by computer

simulations, selecting only complex universes able to harbor life and

reproduce. Cosmological immortality via cosmological artificial selection is

analogous to biological immortality through a chain of reproducing universes

instead of a chain of living entities.

Another argument “concerns the energetics of our universe.” Perhaps

the cosmological energy density trend through time would be a U-shaped curve, with extremely high energy densities at the Big Bang era that decrease as the universe cools down. Locally, the energy rate density then starts to grow exponentially with the appearance of life … The energy rate density is decreasing globally, both as the universe expands, and as organisms senesces inevitably towards death. But, according to the disposable soma theory, organisms invest energy not only for maintenance but also for reproduction. In this context, the origin of life triggering the growth of energy rate density could be interpreted as a maturation phase, towards universe reproduction …

I’m unqualified to assess these highly speculative science fiction scenarios but I think that the future of the universe is largely unknown. When considering a literally unimaginable distant future we can legitimately doubt even the proclamations of our best scientific knowledge. Perhaps Kurzweil was right when he argued “the laws of physics are not repealed by intelligence, but they effectively evaporate in its presence … The fate of the Universe is a decision yet to be made, one which we will intelligently consider when the time is right.”

Finally, Vidal says, the idea of leaving a legacy—whether biological or creative—is a common way to overcome the fear of death. Perhaps then making a universe would be our ultimate legacy. As the philosopher, Steven Cave said: “Perhaps one day we—or some far more evolved successor—will be able to seed new universes that are fit for life. Indeed, perhaps we are already in one, seeded by some earlier civilization.”5

____________________________________________________________________

A recent post discussed Brian Greene’s latest book, Until the End of Time: Mind, Matter, and Our Search for Meaning in an Evolving Universe[image error]. Greene argues that we can find meaning even though the universe destined for extinction. In response, I pointed to scenarios where mind and the universe might be immortal.I have previously written about this topic in “The Origin, Evolution, and Fate of the Cosmos.” Dyson, F. J. 1979. “Time Without End: Physics and Biology in an Open Universe.” Review of Modern Physics 51: 447–60. http://siba.unipv.it/fisica/articoli/... of Modern Physics_vol.51_no.3_1979_pp.447-460.pdf.Landauer, R. 1961. “Irreversibility and Heat Generation in the Computing Process.” IBM Journal of Research and Development 5 (3): 183–91. doi:10.1147/rd.53.0183.Cave, Stephen. 2012. Immortality: The Quest to Live Forever and How It DrivesCivilization. New York: Crown Publishers

Cosmological Immorality

[image error]

Clément Vidal‘s essay, “Cosmological Immortality: How to Eliminate Aging on a Universal Scale” discusses various scenarios of cosmic immortality.1 Vidal says that we might worry about the far future because, for example, we may come to live extremely long lifespans or we simply care about future beings who will live there. With such concerns in mind, he considers two religiously inspired and two scientifically inspired narratives of cosmic immortality.2

The Cosmological Soul – If the many-worlds interpretation of quantum physics is correct, then “our universe keeps branching into parallel universes.” Of course, we know nothing of such universes. Still, believing in”parallel universes could be interpreted in a similar way as the belief that the soul can separate from the body and survive after physical death.” The problem is that this interpretation of quantum mechanics is controversial and also it also doesn’t tell us if those parallel universes would be desirable.

Cosmological Resurrection – Cosmological models that imply a kind of resurrection including cyclical models, the phoenix universe, cosmological natural selection, the chaotic inflation scenario, the ekpyrotic model, or conformal cyclical cosmology. In these models, the cycle goes on, even if each particular universe doesn’t. None of these scenarios necessitate intelligence “but each particular universe could continue to form energy gradients and be able to sustain life.”

Cosmological Survival – Vidal claims that “as long as we can find free energy in the universe, we can hope to live forever.” Turning first to the sun, there have been “proposals to rejuvenate the Sun” in order to radically extend its lifespan. The idea of galactic rejuvenation is even more speculative. However, “the death of stars via supernovae replenish the interstellar medium and in turn allow the formation of new stars.” Perhaps we could someday manage the galaxy like an ecosystem.

It is hard to conceive of universal rejuvenation if for no other reason that even at the speed of light we can’t travel fast enough to reach many of the innumerable receding galaxies. Nonetheless, even as the universe continues to evolve towards its demise there might still be ways to live forever.

The answer is hibernation, and the scenario was articulated in a landmark article about the future of civilization by Dyson.3 Dyson shows that even assuming

a finite supply of energy, it would be possible for a civilization to live forever. An advanced civilization would hibernate longer and longer and thus use less and less energy. Despite a finite energy source, by hibernating longer and longer, and thus using less and less energy, a civilization would be able, in the limit, to live for as long as it wants in its subjective time. Of course, ‘‘life’’ is defined here not in terms of DNA and biochemistry, but as a more general information processing capability. However, this scenario does not work if the universe continues its accelerated expansion.”

Another idea that might lead to intelligence enduring forever is reversible computation.

Landauer4 proved the theoretical possibility of logic gates that consume no energy. Given a computer built out of such gates, a possible solution to the problem of an ever-expanding and slowly dying universe would be to simulate a new universe on a collection of matter that would forever float into emptier and emptier space.

However, most physicists have rejected this idea arguing that ‘‘no finite system can perform an infinite number of computations with finite energy if it is to host evolved information processing.”

Cosmological Legacy – The disposable soma theory says that “it is more efficient to invest energy in reproduction than in indefinite upkeep of the organism. Once the best chances for reproduction are used, thus ensuring the survival of the almost immortal genes (germline), the mortal body (soma) can be disposed of.” Some futurists speculate

that this theory may also apply to the universe. The soma is analogous to the constituents of the universe, with its mortal galaxies, stars, and planets, while the germline is analogous to free parameters that determine immortal physical laws. If we take seriously this fundamental trade-off in energy expenditure between soma and germline, the death of the ‘‘universe’s soma’’ may indeed be inevitable. But its germline, its most delicate physical structure, may be saved if universes are replicable.

Another idea is that future super-intelligent civilizations will engage in cosmological artificial selection.

The artificial selection of universes would be made by computer

simulations, selecting only complex universes able to harbor life and

reproduce. Cosmological immortality via cosmological artificial selection is

analogous to biological immortality through a chain of reproducing universes

instead of a chain of living entities.

Another argument “concerns the energetics of our universe.” Perhaps

the cosmological energy density trend through time would be a U-shaped curve, with extremely high energy densities at the Big Bang era that decrease as the universe cools down. Locally, the energy rate density then starts to grow exponentially with the appearance of life … The energy rate density is decreasing globally, both as the universe expands, and as organisms senesces inevitably towards death. But, according to the disposable soma theory, organisms invest energy not only for maintenance but also for reproduction. In this context, the origin of life triggering the growth of energy rate density could be interpreted as a maturation phase, towards universe reproduction …

I’m unqualified to assess these highly speculative science fiction scenarios but I think that the future of the universe is largely unknown. When considering a literally unimaginable distant future we can legitimately doubt even the proclamations of our best scientific knowledge. Perhaps Kurzweil was right when he argued “the laws of physics are not repealed by intelligence, but they effectively evaporate in its presence … The fate of the Universe is a decision yet to be made, one which we will intelligently consider when the time is right.”

Finally, Vidal says, the idea of leaving a legacy—whether biological or creative—is a common way to overcome the fear of death. Perhaps then making a universe would be our ultimate legacy. As the philosopher, Steven Cave said: “Perhaps one day we—or some far more evolved successor—will be able to seed new universes that are fit for life. Indeed, perhaps we are already in one, seeded by some earlier civilization.”5

____________________________________________________________________

A recent post discussed Brian Greene’s latest book, Until the End of Time: Mind, Matter, and Our Search for Meaning in an Evolving Universe[image error]. Greene argues that we can find meaning even though the universe destined for extinction. In response, I pointed to scenarios where mind and the universe might be immortal.I have previously written about this topic in “The Origin, Evolution, and Fate of the Cosmos.” Dyson, F. J. 1979. “Time Without End: Physics and Biology in an Open Universe.” Review of Modern Physics 51: 447–60. http://siba.unipv.it/fisica/articoli/... of Modern Physics_vol.51_no.3_1979_pp.447-460.pdf.Landauer, R. 1961. “Irreversibility and Heat Generation in the Computing Process.” IBM Journal of Research and Development 5 (3): 183–91. doi:10.1147/rd.53.0183.Cave, Stephen. 2012. Immortality: The Quest to Live Forever and How It DrivesCivilization. New York: Crown Publishers

January 7, 2021

Yes, America Is Descending Into Totalitarianism

(Given recent news in the USA I thought it worthwhile to reprint this post from 4 years ago.)

“In an ever-changing, incomprehensible world the masses had reached the point where they would, at the same time, believe everything and nothing, think that everything was possible and that nothing was true … Mass propaganda discovered that its audience was ready at all times to believe the worst, no matter how absurd, and did not particularly object to being deceived because it held every statement to be a lie … The totalitarian … leaders based their propaganda on the correct psychological assumption that … one could make people believe the most fantastic statements one day, and trust that if the next day they were given irrefutable proof of their falsehood, they would take refuge in cynicism. Instead of deserting the leaders who had lied to them, they would protest that they had known all along that the statement was a lie and would admire the leaders for their superior tactical cleverness.”

~ Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism

For weeks now, I have been reading and blogging about dozens of articles from respected intellectuals from both the right and left who worry about the increasingly authoritarian, totalitarian, and fascist trends in America. Interestingly, when I tried to escape my scholarly bubble by looking for voices arguing that we are NOT heading in this direction, I came up empty. I found partisans or apparatchiks who maintain that all is good, but I couldn’t find hardly any well-informed persons arguing that we have nothing to worry about. I know there are such people, but if so they must be a tiny minority.

Now I did find informed voices saying that, in the long run, things will be fine. That the arc of justice moves slowly forward, that we take 1 step back but then take 2 steps forward, etc. Such thinking about things from a larger perspective resonates with me. I write about big history and believe there may be directionality to cosmic evolution. I’ve argued that the universe is becoming self-conscious through the emergence of conscious beings, and I’ve even hypothesized that humans may become post-humans by utilizing future technologies. So I can’t be accused of ignoring the big picture.

However, at the moment, such concerns seem irrelevant. Yes, it may be true that life is getting better in many ways, as Steven Pinker recently noted. But such thoughts provide little consolation for the millions who suffer in the interim. When people lack health care and educational opportunities; when they are deported, tortured, falsely imprisoned, or killed in wars; when they live in abject poverty surrounded by gun violence and suffer in a myriad of other ways, none of this is ameliorated by appeals to a faraway future. Even if the world is better in a thousand years, that provides small consolation now.

What is almost self-evident is that America is now becoming more corrupt, and at a dangerously accelerating rate. In response, we must resist becoming like those of whom Yeats said: “The best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity.” So I state unequivocally that I agree with the vast majority of scholars and thinkers—recent trends reveal that the USA is becoming more authoritarian, totalitarian, and fascist. The very survival of the republic is now in doubt.

Of course, I could be mistaken—it’s hard to predict the future. Moreover, I am not a scholar of Italian history, totalitarianism, or mob psychology that enables fascist movements. But I do know that all of us share a human genome; we are more alike than different. Humans are capable of racism, sexism, xenophobia, cruelty, violence, religious fanaticism, and more. We are modified monkeys —in many ways we are a nasty species. As Mark Twain said: “Such is the human race … Often it does seem such a pity that Noah and his party did not miss the boat.”

Thus I resist the idea that fascism can happen in Germany, Italy or Russia, but not in America. It can happen here, and the signs point in an ominous direction. Furthermore, the United States was never a model of liberty or justice. The country was (in large part) built on slave labor as well as genocide at home and violent imperialism abroad. It is a first-world outlier in terms of incarceration rates and gun violence; it is the only developed country in the world without national health and childcare; it has outrageous levels of income inequality and little opportunity for social mobility; it ranks near the bottom of lists of social justice; it is one of the few countries in the world to condemn Article 25 of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights; and it is consistently ranked as the greatest threat to world peace and the world’s most hated country.

Furthermore, signs of its dysfunction continue to grow. If authoritarian political forces don’t get their way, they shut down the government, threaten to default on the nation’s debt, fail to fill judicial vacancies, deny people health-care and family planning options, conduct congressional show trials, suppress voting, gerrymander congressional districts, support racism, xenophobia, and sexism, and spread lies and propaganda. These aren’t signs of a stable society. As the late Princeton political theorist Sheldon Wolin put it:

The elements are in place [for a quasi-fascist takeover]: a weak legislative body, a legal system that is both compliant and repressive, a party system in which one party, whether in opposition or in the majority, is bent upon reconstituting the existing system so as to permanently favor a ruling class of the wealthy, the well-connected and the corporate while leaving the poorer citizens with a sense of helplessness and political despair, and, at the same time, keeping the middle classes dangling between fear of unemployment and expectations of fantastic rewards once the new economy recovers. That scheme is abetted by a sycophantic and increasingly concentrated media; by the integration of universities with their corporate benefactors; by a propaganda machine institutionalized in well-funded think tanks and conservative foundations; by the increasingly closer cooperation between local police and national law enforcement agencies aimed at identifying terrorists, suspicious aliens, and domestic dissidents.

Now with power in the hands of an odd mix of plutocrats, corporatists, theocrats, racists, sexists, egoists, psychopaths, sycophants, anti-modernists, and the scientifically illiterate, there is no reason to think that they will surrender their power without a fight. You might think that if income inequality grows, individual liberties are further constricted, or millions of people are killed at home or abroad, that people will reject those in power. But this assumes we live in a democracy. And a compliant and misinformed public can’t think, act or vote intelligently. If you control your citizens with sophisticated propaganda, mindless entertainment, and a shallow consumer culture, you can persuade them to support anything. With better methods of controlling and distorting information will come more control over the population. And, as long the powerful believe they benefit from an increasingly totalitarian state, they will try to maintain it. Most people like to control others; they like to win.

An outline of how we might quickly descend into madness was highlighted by David Frum, the conservative and former speechwriter for President George W. Bush. Frum envisions the following scenario which is, I believe, as prescient as it is chilling:

1) … I don’t imagine that Donald Trump will immediately set out to build an authoritarian state; 2) … his first priority will be to use the presidency to massively enrich himself; 3) That program of massive self-enrichment … will trigger media investigations and criticism by congressional Democrats; 4) ….Trump cannot tolerate criticism … always retaliating against perceived enemies, by means fair or foul; 5) … Trump’s advisers and aides share this belief [they] … live by gangster morality; 6) So the abuses will start as payback. With a compliant GOP majority in Congress, Trump admin can rewrite laws to enable payback; 7) The courts may be an obstacle. But w/ a compliant Senate, a president can change the courts … 8) … few [IRS] commissioners serve the full 5 years; 9) The FBI seems … pre-politicized in Trump’s favor … 10) Construction of the apparatus of revenge and repression will begin opportunistically & haphazardly. It will accelerate methodically …

Let me tell a personal story to help explain the cutthroat, no holds bar political world that is rapidly growing in America today. Years ago I played high-stakes poker. It started out innocently, a few friends having a good time playing for pocket change. Slowly the stakes grew, forcing me to study poker if I didn’t want to lose money. My studies paid off, and I began to win consistently. I even lived in Las Vegas for about 2 years playing poker professionally.

Then I start playing with strangers, assuming my superior poker skills would prevail. But soon I started losing; finding out later that I was cheated. (I was being cold decked.) It turned out that my opponents played by a different rule—their rule was that I wasn’t leaving the game with any money. Then I discovered that some people will go further, robbing you at gunpoint of the money you had won. (This actually happened to me once.) Once the gentleman’s rules of poker no longer applied, nothing was off-limits.

Similarly, once the agreement to play by democratic rules is violated, all bets are off. For example, you begin to ignore the other parties’ Supreme Court nominees or threaten to default on the nation’s debts, or ignore obstruction of justice in order to get your way. This signals our entry into the world of mobsters and rogue nations, an immoral world. The logical end of this state of affairs is violence.

This describes the current political situation. The US Congress was once characterized by comity but is so no longer. From the period after World War II to about 1980, the political parties in the USA generally compromised for the good of the nation. The radicalization of the Republican party began in the 1980s and by the mid-1990s, and with Republican control of the House of Representatives, the situation dramatically deteriorated. (Newt Gingrich is more responsible for this than anyone; he is one of this century’s worst Americans.) One side was determined to get their way and wouldn’t compromise. It was now no holds barred.

In other words, American politics has entered a situation that game-theorists call a prisoner’s dilemma. A prisoner’s dilemma is an interactive situation in which it is better for all to cooperate rather than for no one to do so, yet it is best for each not to cooperate, regardless of what the others do. For example, we would have a better country if everyone paid their share of taxes, but it is best for any individual, say, Donald Trump, not to pay taxes if they can get away with it. Put differently, you do best when you cheat at poker and don’t get caught, or control the situation if you do get caught. In politics this means you try to hide your crimes, but vilify the press or whistleblowers if you are exposed.

If successful in usurping power, you win in what the philosopher Thomas Hobbes called the state of nature. Hobbes said that in such a state the only values are force and fraud— you win if you dominate, enslave, incarcerate, or eviscerate your opponents. But the problem with this straightforward egoism, Hobbes thought, was that people were “relative power equals.” That is, people can form alliances to fight their oppressors. So while what Hobbes’ called the right of nature tells you to use whatever means possible to achieve power over others, the law of nature paradoxically reveals that this will lead to continual warfare. The realization of this paradox should lead people to give up their quest for total domination and, thus, cooperate. They do so by signing a social contract in which they agree to and abide by, social and political rules.

But if we live in a country where people are radically unequal in their power—Democrats vs. Republicans; unions vs. corporations; secularists vs theocrats; African-Americans vs. white nationalists—then those in power won’t compromise with the less powerful. When the powerful few are imbued with the idea that they are better people with better ideas, and when they are drunk with their power, you can bet that the rest of us will suffer.

In short, it is a centuries-old story. People want power. They will do almost anything to attain it. When they have it they will try to keep it, and they will try to divide those who should join together to fight them. Hence they promote racism, sexism, homophobia, xenophobia, etc. In the end, a few seek wealth and power for themselves, others want a decent life for everyone. Right now the few are winning.

January 4, 2021

Brian Greene’s “Until the End of Time”

[image error]

Brian Greene is a theoretical physicist, mathematician, string theorist, and Professor at Columbia University. His latest book, Until the End of Time: Mind, Matter, and Our Search for Meaning in an Evolving Universe[image error], explores the question of how life can be meaningful in a universe destined for extinction. It is a brave, profound, wise, and erudite work.

“… a moment after the Big Bang, life arose, briefly contemplated its existence within an indifferent cosmos, and dissolved away.” ~ Brian Greene

Green believes that religion, science, philosophy, art, and more proceed from fear of death. We are fleeting, hence we feel the attraction of something timeless that we might participate in. For Greene, this has manifested itself in his lifelong pursuit of mathematical and scientific laws. “We fly to beauty,” as Emerson put it, “as an asylum from the terrors of finite nature.”

In other words, we are at once splendidly unique—capable of literature, art, music, science, etc.—yet we return to dust. As Ernest Becker wrote in The Denial of Death[image error], “Man is literally split in two: he has an awareness of his own splendid uniqueness in that he sticks out of nature with a towering majesty, and yet he goes back into the ground a few feet in order blindly and dumbly to rot and disappear forever.”

Knowing all this we try to prevent death from erasing us by connecting to family, team, religion, nation, social movements, etc. Or we try to win or conquer, or gain wealth, power, or status. Through our actions and connections, we hope to suppress what William James called “the worm at the core of all our usual springs of delight.” For sanity’s sake, we try to forget death and go about our usual concerns.

Our coping mechanisms typically also involve religious narratives about the afterlife, reincarnation, and the like. But science too has a story about where we came from, where we’re going, our struggle to survive and understand, and our search for meaning.

The scientific story hinges on two salient universal influences. Entropy, the continual increase of disorder in the universe, and evolution, which explains how organized life took hold in such a universe. Much of the book explains the scientific story. From the Big Bang onward to the molecular Darwinism that results from the sun raining light and heat on the molecules of the earth, to life developing under evolutionary pressure according to Darwinian rules eventually resulting in self-conscious beings who plan, organize, learn, teach, and communicate.

The acquisition of language in turn made possible the telling of first religious and later scientific narratives. Our behaviors evolved under evolutionary pressure too; some enhanced our chance at survival and reproduction, others did not. The evolution of our brains allowed us to dominate the world, but these brains became aware of their own mortality. This is disconcerting, but we learned to cope with the stories we told ourselves.

And what lies in the future according to our best scientific knowledge? While Green admits “there are significant uncertainties … and … I live for the possibility that nature will … reveal surprises … we can’t now fathom” what science tells us about the far future isn’t heartening. It seems that mind simply can’t exist in the distant future because entropy will make thought physically impossible. Life is most likely unimaginably transitory on cosmic timescales; all will disappear into the void.

How then to avoid the dread of really feeling this in our bones? That all thought and accomplishment, all hopes and dreams will end forever? In response, Greene suggests marveling and being grateful that we are conscious at all. The universe will host life and mind only temporarily so appreciate it by living in and revering the now. (This is easy to say for someone in Greene’s or my position in life; almost impossible for the many who are constantly suffering.) In short, we must find our own meaning. But is this possible?

The problem is that while we “have a pervasive longing to be part of something lasting, something larger” our somethings will become nothing. everything dies—us, our species, life and mind, and the universe. The key here is the idea of universal death. Greene grants that we may become “well-adjusted immortals” but avoiding the death of the cosmos seems almost impossible. And this realization is devastating for any conception of meaning. Why?

Consider the difference between all life dying in 30 days or in 102500years. Most people think that if all life were to end in 30 days life would be rendered meaningless. But if it does then so should the fact that all life will end in the unimaginably distant future. The truth is that we are evanescent, the universe doesn’t care about us, and nothing of us will (probably) survive.

Yet Greene refuses to be forlorn. It is still extraordinary that we exist as conscious beings who can step outside of time. Perhaps we cant solve the great questions (why is there something and not nothing, how did consciousness emerge, etc.) because our brains were designed mostly for survival. Or maybe minds will eventually figure it all out.

Either way Greene says, we have deciphered much, especially about how math and logic hold the universe together. And what we can say about the meaning of life is that

There is no final answer hovering in the depths of space awaiting discovery … Instead, certain special collection of particles … can create purpose. … in our quest to fathom the human condition, the only direction to look is inward … to the highly personal journey of creating our own meaning.

Reflections

Greene does discuss some fantastic scenarios where mind might find a way to escape universal death. He admits that “A big unknown … is whether intelligent life will be able to intercede in the cosmic unfolding …” However, he regards speculating about such matters over cosmic time scales as “a fool’s errand.” To his credit, his philosophical response is to the far future that physics reveals as most likely.

But others like Ray Kurzweil argued in The Age of Spiritual Machines: When Computers Exceed Human Intelligence[image error] that “the laws of physics are not repealed by intelligence, but they effectively evaporate in its presence … The fate of the Universe is a decision yet to be made, one which we will intelligently consider when the time is right.”

Or as I have written previously,

Now we might avoid our cosmic descent into nothingness and its implications if one of these conjectures is true: the death of our universe brings about the birth of another one; the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics is true; other universes exist in a multiverse; or, if all descend into nothingness, a quantum fluctuation brings about something from this nothing. Or maybe nothingness is impossible as Parmenides argued long ago …

As for the cosmos, our posthuman descendants may be able to use their superintelligence to avoid cosmic death by altering the laws of physics or escaping to other universes. And even if we fail other intelligent creatures in the universe or multiverse might be able to perpetuate life indefinitely in ways we can’t even imagine. If superintelligence pervades the universe, it may become so powerful as to ultimately decide the fate of the cosmos. Perhaps then cosmic death isn’t foreordained either.

I understand the highly speculative nature of these conjectures but they do give us the smallest ray of hope that the end of all life isn’t inevitable. Still, as I have said before

… if nothingness is our fate—no space, no time, nothing for all eternity—then all seems futile. We may have experienced meaning while we lived, and the cosmos may have been slightly meaningful while it existed, but if everything vanishes for eternity isn’t it all pointless?

So I find it hard to accept the situation we’re in. Yes, if universal death is the end then all we can do is to try to enjoy the brevity of life as best we can while expressing care and concern for our fellow travelers on this lonely and ultimately one-way road. And this is probably the truth about our situation. So we should practice acceptance and resignation and appreciation for what we have. We should see the glass half full.

Yet I still hear Dylan Thomas words ringing in my ears,

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

I would like to thank Professor Greene for his great addition to the meaning of life literature.

December 30, 2020

Cosmic Evolution and the Meaning of Life

[image error](This essay was reprinted in Scientia Salon; Institute for Ethics & Emerging Technologies; High Existence, and Humanity+ Magazine)

Are there trends in evolution — cosmic, biological, and cultural — that support the claim that life is meaningful, or is becoming meaningful, or is becoming increasingly meaningful? Perhaps there is a progressive direction to evolution, perhaps the meaningful eschatology of the universe will gradually unfold as we evolve, and perhaps we can articulate a cosmic vision to describe this unfolding — or perhaps not.

Has there been biological progress?

The debate between those who defend evolutionary progress and those who deny it has been ongoing throughout the history of biology. On the one hand, more recent biological forms seem more advanced, on the other hand, no one agrees on precisely what progress is. Darwin’s view of the matter is summarized nicely by Timothy Shanahan: “while he rejected any notion of evolutionary progress, as determined by a necessary law of progression, he nonetheless accepted evolutionary progress as a contingent consequence of natural selection operating within specified environments.” [1] This fits well with Darwin’s own words:

There has been much discussion whether recent forms are more highly developed than ancient . . . But in one particular sense the more recent forms must, on my theory, be higher than the more ancient; for each new species is formed by having had some advantage in the struggle for life over other and preceding forms. I do not doubt that this process of improvement has affected in a marked and sensible manner the organization of the more recent and victorious forms of life, in comparison with the ancient and beaten forms; but I can see no way of testing this sort of progress. [2]

The most vociferous critic of the idea of biological progress was Harvard’s Stephen Jay Gould who thought progress was an annoying and non-testable idea that had to be replaced if we are to understand biological history. According to Gould, what we call evolutionary progress is really just a random moving away from something, not an orienting toward anything. Starting from simple beginnings, organisms become more complex but not necessarily better. In Gould’s image, if a drunk man staggers from a wall that forces him to move toward a gutter, he will end up in the gutter. Evolution acts like that wall pushing individuals toward behaviors that are mostly random but statistically predictable. Nothing about evolution implies progress.

The biologist Richard Dawkins is more sanguine regarding progress, arguing that if we define progress as an adaptive fit between organism and environment then evolution is clearly progressive. To see this consider a predator and prey arms race, where positive feedback loops drive evolutionary progress. Dawkins believes in life’s ability to evolve further, in the “evolution of evolvability.” He believes in progressive evolution, in that sense.

Darwin seemingly reconciled these two views … as the forms became complicated, they opened fresh means of adding to their complexity … but yet there is no necessary tendency in the simple animals to become complicated although all perhaps will have done so from the new relations caused by the advancing complexity of others … if we begin with the simpler forms and suppose them to have changed, their very changes tend to give rise to others.[3]

Simple forms become increasingly complex, thus stimulating the complexity of other forms. This did not happen by necessity and no law needs to drive the process. Nonetheless, competition between organisms will likely result in progressively complex forms.

There is probably no greater authority on the idea of evolutionary progress than Michael Ruse whose book, Monad to Man: The Concept of Progress in Evolutionary Biology, is the most comprehensive work on the subject. Ruse observes that museums, charts, displays, and books all depict evolution as progressive, and he thinks that the concept of progress will continue to play a major role in evolutionary biology for the following reasons.

First, as products of evolution, we are bound to measure it from our own perspective, thus naturally valuing the intelligence that asks philosophical questions. Second, whatever epistemological relativists think, nearly all practicing scientists believe their theories and models get closer to the truth as science proceeds. And scientists generally transfer that belief in scientific progress to a belief in organic progress. Finally, Ruse maintains that the scientists drawn to evolutionary biology are those particularly receptive to progressive ideas. Evolution and the idea of progress are intertwined and nearly inseparable.

Has there been cultural progress?

Cosmic evolution evokes the idea of evolutionary progress while progressivism imbues the work of most biologists, a trend Ruse thinks will continue. When we turn to culture, a compelling argument can be made for the reality of progressive evolution. The historian Will Durant argued for cultural progress, a conclusion he believed followed from considering certain elements of human history, while Jean Piaget made the case for cognitive progress, based on his studies of cognitive development in children and his analysis of the history of science. The science writer Robert Wright believes in a generally progressive evolution based on the structure of non-zero-sum interactions, whereas Steven Pinker counters that complexity and cooperation are sub-goals of evolution, not its natural destiny.

While the overall strength of the arguments for evolutionary progress is unclear, we cannot gainsay that such arguments have philosophical merit. Clearly, there have been progressive trends in evolution, which suggests that life as a whole may become increasingly meaningful.

That is in line with a number of other thinkers who have argued for the relevance of evolution to meaning. Daniel Dennett extends the heuristic reach of evolution, showing how it acts as a universal solvent that eats through philosophical problems, while the skeptic Michael Shermer says that we create provisional meanings in our lives, even though our existence depends on a billion evolutionary happenstances. The scientist Steve Stewart-Williams argues that the universe does have purposes since we have purposes and we are part of the universe, while the philosopher John Stewart claims that the universe will be increasingly meaningful if we direct the process.

Still, other philosophers have argued that evolution is irrelevant to meaning; Wittgenstein notoriously maintained that “Darwin’s theory has no more to do with philosophy than any other hypothesis in natural science.” [4] Yet this claim was made in a philosophical milieu where the scope of philosophical inquiry was narrow, whereas today the impact of scientific theories on philosophy is enormous. Today most thinkers would say that the emergence of conscious purposes and meanings in cosmic evolution is relevant to concerns about meaning.

Turning to grand cosmic visions, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin articulated a universal vision of the evolutionary process, with the universe moving toward a fully meaningful endpoint. Jacques Monod questioned Teilhard’s optimism, noting that biology does not reveal that life is meaningful. Julian Huxley conveys a vision — similar to Teilhard’s but without the religious connotations — which encourages us to play the leading role in the cosmic drama by guiding evolution to realize its possibilities, thereby finding meaning for ourselves in the process. E.O. Wilson also believes that the evolutionary epic is mythic and sweeping and he exhorts us to create a better future. Thus many thinkers believe that evolution is both progressive and relevant to meaning. For Teilhard, Huxley, and Wilson, life is meaningful because it evolves, and we live meaningful lives precisely because we play a central role in this evolving meaning.

Evolution as metaphysics

So a study of cosmic evolution can support the claim that life has become increasingly meaningful, a claim buttressed primarily by the emergence of beings with conscious purposes and meanings. Where there once was no meaning or purpose — in a universe without mind — there are now both meanings and purposes.

These meanings have their origin in the matter which coalesced into stars and planets, which in turn supported organisms that evolved bodies with brains and their attributes — behavior, consciousness, personal identity, freedom, value, and meaning. Meaning has emerged during the evolutionary process. It came into being when complexly organized brains, consisting of constitutive parts and the interactive relationships between those parts, intermingled with physical and then cultural environments. This relationship was reciprocal — brains affected biological and cognitive environments which in turn affected those brains. The result of this interaction between organisms and environments was a reality that became, among other things, infused with meaning.

But will meaning continue to emerge as evolution moves forward? Will progressive evolutionary trends persevere to complete or final meaning, or to approaching meaning as a limit? Will the momentum of cognitive development make such progress nearly inevitable? These are different questions — ones that we cannot answer confidently. We could construct an inductive argument, that the past will resemble the future in this regard, but such an argument is not convincing. For who knows what will happen in the future? The human species might bring about its own ruin tomorrow or go extinct due to some biological, geophysical, or astronomical phenomenon. We cannot bridge the gap between what has happened and what will happen. The future is unknown.

All this leads naturally to another question. Is the emergence of meaning a good thing? It is easy enough to say that conscious beings create meaning, but it is altogether different to say that this is a positive development. Before consciousness, no one derived meaning from torturing others, but now they sometimes do. In this case, a new kind of meaning emerged, but few think this is a plus. Although we can establish the emergence of meaning, we cannot establish that this is good.

Still, we fantasize that our scientific knowledge will improve both the quality and quantity of our lives. We will make ourselves immortal, build ourselves better brains, and transform our moral natures — making life better and more meaningful, perhaps fully meaningful. We will become pilots worthy of steering evolution to fantastic heights, toward creating a heaven on earth or in simulated realities of our design. If meaning and value continue to emerge we will find meaning by partaking in, and hastening along, that very process. As a result of past meanings and as the conduit for the emergence of future ones, we could be the protagonists of a great epic that ascends higher, as Huxley and Teilhard had hoped.

In our imagination, we exist as links in a golden chain leading onward and upward toward greater levels of being, consciousness, joy, beauty, goodness, and meaning — perhaps even to their apex. As part of such a glorious process, we find meaning instilled into our lives from previously created meaning, and we reciprocate by emanating meaning back into a universe with which we are ultimately one. Evolutionary thought, extended beyond its normal bounds, is an extraordinarily speculative, quasi-religious metaphysics in which a naturalistic heaven appears on the horizon.

Conclusion: sobriety and skepticism

Yet, as we ascend these mountains of thought, we are brought back to earth. When we look to the past we see that evolution has produced meaning, but it has also produced pain, fear, genocide, extinction, war, loneliness, anguish, envy, slavery, despair, futility, torture, guilt, depression, alienation, ignorance, torture, inequality, misogyny, xenophobia, superstition, poverty, heartache, death, and meaninglessness. Surely serious reflection on this misery is sobering. Turning to the future, our optimism must be similarly restrained. Fantasies about where evolution is headed should be tempered, if for no other reason than that our increased powers can be used for evil as well as for our improvement. Our wishes may never be fulfilled.

But this is not all. It is not merely that we cannot know if our splendid speculations are true — which we cannot — it is that we have an overwhelmingly strong reason to reject our flights of fancy. And that is that humans are notorious pattern-seekers, story-tellers, and meaning-makers who invariably weave narratives around these patterns and stories to give meaning to their lives. It follows that the patterns of progress we glimpse likely exist only in our minds. There is no face of a man on Mars or of Jesus on grilled cheese sandwiches. If we find patterns of progress in evolution, we are probably victims of simple confirmation bias.

After all, progress is hardly the whole story of evolution, as most species and cultures have gone extinct, a fate that may soon befall us. Furthermore, as this immense universe (or multi-verse) is largely incomprehensible to us, with our three and a half pound brains, we should hesitate to substitute an evolutionary-like religion for our frustrated metaphysical longings. We should be more reticent about advancing cosmic visions, and less credulous about believing in them. Our humility should temper our grandiose metaphysical speculations. In short, if reflection on a scientific theory supposedly reveals that our deepest wishes are true, our skeptical alarm bell should go off. We need to be braver than that, for we want to know, not just to believe. In our job as serious seekers of the truth, the credulous need not apply.

In the end, cosmic and biological evolution — and later the emergence of intelligence, science, and technology — leave us awestruck. The arrival of intelligence and the meaning it creates is important, as Paul Davies put it: “the existence of mind in some organism on some planet in the universe is surely a fact of fundamental significance. Through conscious beings the universe has generated self-awareness. This can be no trivial detail, no minor byproduct of mindless, purposeless forces. We are truly meant to be here.” [5] Similar ideas reverberate in the work of Simon Conway Morris. He argues that if intelligence had not developed in humans, it would have done so in another species — in other words, the emergence of intelligence on our planet was inevitable [6].

I agree with both Davies and Morris that mind and its attendant phenomena are important, but it doesn’t follow that we are meant to be here or that intelligence was inevitable. It’s only because we value our life and intelligence that we succumb to such anthropocentrism. Homo sapiens might easily have never been, as countless events could have led to their downfall. This should give us pause when we imbue our existence with undue significance.

We were not inevitable, we were not meant to be here — we are serendipitous. The trillions and trillions of evolutionary machinations that led to us might easily have led to different results — ones that didn’t include us. As for the inevitability of intelligence, are we really to suppose that dinosaurs, had they not been felled by an asteroid, were on their way to human-like intelligence? Such a view strains credulity; dinosaurs had been around for many millions of years without developing greater intelligence. We want to believe evolution had us as its goal — but it did not — we were not meant to be. We should forgo our penchant for detecting patterns and accept our radical contingency. Like the dinosaurs, we too could be felled by an asteroid [7].

Thus we cannot confidently answer all of the questions we posed at the beginning of this essay in the affirmative. We can say that there has been some progress in evolution and that meaning has emerged in the process, but we cannot say these trends will continue or that they were good. And we certainly must guard against speculative metaphysical fantasies, inasmuch as there are good reasons to think we are not special. We do not know that a meaningful eschatology will gradually unfold as we evolve, much less that we could articulate a cosmic vision to describe it. We don’t even know if the reality of any grand cosmic vision is possible. We are moving, but we might be moving toward our own extinction, toward universal death, or toward eternal hell. And none of those offer much comfort.

We long to dream but always our skepticism awakens us from our Pollyannaish imaginings. The evolution of the cosmos, our species, and our intelligence give us some grounds for believing that life might become more meaningful, but not enough to satisfy our longings. We want to believe that tomorrow will really be better than yesterday. We want to believe with Teilhard and Huxley that a glorious future awaits but, detached from our romanticism, we know that Jacques Monod may be right — there may be no salvation, there may be no comfort to be found for our harassed souls.

Confronted with such meager prospects and the anguish that accompanies them, we are lost, and the most we can do, once again, is hope. That doesn’t give us what we want or need, but it does give us something we don’t have to be ashamed of. There is nothing irrational about the kind of hope that is elicited by, and best expressed from, an evolutionary perspective. Julian Huxley, scientist and poet, best conveyed these hopes:

I turn the handle and the story starts:

Reel after reel is all astronomy,

Till life, enkindled in a niche of sky,

Leaps on the stage to play a million parts.

Life leaves the slime and through the oceans darts;

She conquers earth, and raises wings to fly;

Then spirit blooms, and learns how not to die,

Nesting beyond the grave in others’ hearts.

I turn the handle; other men like me

Have made the film; and now I sit and look

In quiet, privileged like Divinity

To read the roaring world as in a book.

If this thy past, where shall thy future climb,

O Spirit, built of Elements and Time![8]

____________________________________________________________________

Notes.

[1] Timothy Shanahan, “Evolutionary Progress from Darwin to Dawkins.”

[2] Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or, the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life (New York: Cosimo, Inc., 2007), 211.

[3] Barrett, P., Gautrey, P., Herbert, S., Kohn, D., and Smith, S., Charles Darwin’s Notebooks, 1836-1844 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1987).

[4] Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, trans. D.F. Pears and B.F. McGuiness (London: Routledge & Paul Kegan, 1961), 25.

[5] Paul Davies, The Mind of God: The Scientific Basis for a Rational World (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993), 232.

[6] Simon Conway Morris, Life’s Solution: Inevitable Humans in a Lonely Universe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003).

[7] Had the course of the asteroid 2005 YU55 that passed the earth on November 8, 2011 been slightly altered, millions might have died and this essay not written.

[8] Julian Huxley, ‘Evolution: At the Mind’s Cinema’ (1922), in The Captive Shrew and Other Poems of a Biologist (London: Basil Blackwell, 1932), 55.

(Note. This essay originally appeared on this blog on January 26, 2015.)

December 23, 2020

Most Popular Post of 2020

[image error]An artist’s depiction of the interconnections between blogs in the “blogosphere.”

Here are the ten most popular posts on my blog from this past year.

10. With 12,000+ views,

9. With 16,000+ views,

8. With 17,000+ views,

7. With 18,000+ views,

6. With 18,000+ views,

5. With 21,000+ views, (This is also my 3rd most viewed post all-time with 135,000+ views)

4. With 25,000+ views, (This is also my 2nd most viewed post all-time with 155,000+ views)

3. With 26,000+ views,

2. With 26,000+ views,

1. With 42,000+ views, (This is also my most viewed post all-time with 165,000+ views)

December 21, 2020

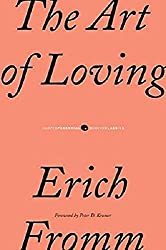

The Art of Loving

I previously have written a number of columns on love but I have not mentioned a small book I read in my early twenties, and the first book I gave to Jane—who would later become my wife—just weeks after meeting her—Erich Fromm’s, The Art of Loving. It begins:

Is love an art? Then it requires knowledge and effort. Or is love a pleasant sensation, which to experience is a matter of chance, something one “falls into” if one is lucky? This little book is based on the former premise, while undoubtedly the majority of people today believe it is the latter.

Fromm thought that we misunderstand love for many reasons. First, we see the problem of love as one of being loved rather than one of loving. We try to be richer, more popular, or more attractive instead of learning how to love. Second, we think of love in terms of finding an object to love, rather than of it being a faculty to cultivate. We think it is hard to find someone to love but easy to love, when in fact the opposite is true. (Think of movies where after a long search the lovers finally connect and then the movie ends. But it’s the happily ever after that’s the hard part.) Finally, we don’t distinguish between “falling” in love and what Fromm calls “standing” in love. If two previously isolated people suddenly discover each other it is exhilarating. But such feelings don’t last. Real love involves standing in love; it is an art we learn after years of practice, just as we would learn any other art or skill.

In the end, though loving is difficult to learn and practice, it is most worthwhile and more important than money, fame, or power. The mystery of existence reveals itself—if it ever does—through things like relating to nature and productive work but, most of all, through our relationships with other people. Thus to experience the depths of life, we should cultivate the art of loving.

And as for Jane, the original handwritten inscription I wrote in the book is still apropos:

To Jane

In whose heart

I have perceived

a great deal of

warmth and love …

__________________________________________________________________________

(Note. This post first appeared on this blog on July 29, 2014.)

December 17, 2020

Transcendence Without The Bull

[image error]

by Lawrence Rifkin MD

A rush of powerful, transforming emotion. A bolt of altered perspective. A love that overwhelms. An unmediated encounter with pure beauty. A profound realization of significance—or insignificance. When a humanist has a “wow” experience, by what name should we call it? Transcendence?

Transcendence is a word that makes many who embrace humanism and naturalism recoil. And for understandable reason, with its connotations to both supernaturalism and mumbo-jumbo. Can transcendence be expressed and understood in a way that is humanistic, rather than supernatural?

The answer is yes. For humanism to not explicitly embrace such experiences risks limiting humanism’s appeal and reducing its potential for personal meaning. If a culture does not provide explicit links between such profound experiences and a naturalistic interpretation, these powerful and possibly transformational experiences can easily be misinterpreted, by default, as being part of a provincial religious story.

The rush of naturalistic transcendence is available in several ways: when we glimpse universals, when we treasure particulars, and when we expand our consciousness. All these types of experiences can be both transcendent and fully understood as naturalistic phenomena in a naturalistic world.

One common understanding of transcendence is an encounter with a world beyond ourselves, beyond full comprehension. But why must this be interpreted as supernatural? A naturalistic world offers an abundance of experiences and understandings beyond our individual lives. There is deep time, extending unfathomably into the past and unfathomably into the future, with our entire lives constituting but a blip. There is deep space, with hundreds of billions of galaxies separated by incomprehensibly vast distances, in which Earth is but a speck. There are concepts of energy, mathematics, human history, and evolution. There is joy in the idea that consciousness even exists. There is the experience of love. Neither a deity nor a complete loss of individuality to a greater power is necessary to experience the grandeur of these great mysteries. There’s an awful lot that is bigger than any of us.

And when we get it, really get it, when intellect and emotions come rushing together, transcendence seems a powerful word for that experience. After he survived a heart attack, Abraham Maslow felt as if “everything gets doubly precious, gets piercingly important. You get stabbed by things, by flowers and by babies and by beautiful things…every single moment of every single day is transformed.” Charles Darwin, in a letter to his wife Emma in 1858, described the following experience: “I fell asleep on the grass, and awoke with a chorus of birds singing around me…and it was as pleasant and rural a scene as I ever saw, and I did not care one penny how any of the beasts and birds had been formed.”

Transcendence—experience beyond the ordinary—is perhaps most powerfully felt not in our encounter with universals, but when we are overcome by particulars, experiences that are supremely individual. For some, it is triggered by new romance, an exercise high, the culminating moment of a particular song, knowing in the core of your being that you are doing something good, sudden acceptance of profound insight, or sex. It’s a very personal thing. Every once in a while, out of the blue, I’ll look at my children doing something commonplace—playing sports, sleeping, or just laughing—and I’ll feel it. The wow of being a parent. The rush of life’s transience and joys. The sense of meaning. It’s the highest of highs tinged with sadness all at once. It’s intensely personal—these are my children, my life. Supernatural explanations at such times are as unnecessary as they are factually inaccurate.

Then there are transcendent experiences of consciousness that are not “about” anything in particular. These take many forms, from contemplative awareness, to hallucinogenic consciousness expansion, to self-actualized acceptance of self and world. Regarding the possibilities of meditation, Sam Harris notes a feeling of being utterly at ease in the world, a state which fully transcends the apparent boundaries of the self. “There are states of consciousness,” Harris writes, “for which phrases like ‘boundless love and compassion’ do not seem overblown.” Regarding his experience with psychedelic drugs Harris writes “It is one thing to be awestruck by the sight of a giant redwood and to be amazed at the details of its history and underlying biology. It is quite another to spend an apparent eternity in egoless communion with it.”

Humanists need not de-emphasize all these types of powerfully real human experiences. The important thing for those having the experience is to not discount reason, and not misinterpret the experience as part of some supernatural tale. Those who seek transcendent experiences and understandings need not seek religious or new-age groups as their only option. Numinous is not synonymous with miraculous.

Transcendence properly understood—a naturalistic transcendence—embraces the non-rational, not the irrational. For the good of individuals and society, irrationality must be confronted and kept out of public policy. Non-rational transcendent emotions, on the other hand, are harmonious with reason, evidence, and naturalism. They can be cherished as supreme human experiences.

(“Transcendence Without The Bull,” appeared in The New Humanism, Sept. 2011. Reprinted with the author’s permission.)

December 14, 2020

Summary of Uscinski’s, “On Conspiracy Theories: A Primer”

© Darrell Arnold Ph.D.– (Reprinted with Permission)

Joseph Uscinski’s Conspiracy Theories: A Primer[image error] (Roman & Littlefield, 2019) is a helpful primer, providing, as Uscinski notes in the preface, not a complete picture of conspiracy theories, but a “complete enough picture.”

While I think the book is useful, my comments here focus on three critical points in particular: 1) Uscinski’s attempt to neutralize the definition of “conspiracy theory” runs too much against the grain of the common language pejorative use of the term to be effective. 2) His distinction between “conspiracy facts” and “conspiracy theories,” based on the former aligning with “settled science,” operates with an overly simplistic model of science and of what is considered good evidence in the social sciences and humanities. 3) These two issues lead to a quite unhelpful result in that he lumps together theories of quite different seriousness as being conspiracy theories, without providing any means to differentiate usefully between those that it is important to consider and those that are utterly absurd. This in fact is a great disservice and opens his work to serious ideological misuses–whether intended or not.

One of Uscinski’s points in the book is that conspiracy theories are not rare. In fact, he argues that they are a “part of the human condition. Everyone believes at least one” (125). The truth of these assertions, of course, turns on the definitions of conspiracy and conspiracy theory. Uscinski, for his part, characterizes conspiracies as involving “as small group of powerful individuals acting in secret for their own benefit and against the common good” (22).

He then goes on to offer a neutral characterization of conspiracy theories, simply defining them as theories about conspiracies. He means to lend his voice to those seeking to overturn the view that all conspiracy theories are wild and necessarily false. Conspiracies exist; and people have theories about them. As Uscinski puts it, “Conspiracy theories are accusatory ideas that could be either true or false, and they contradict the proclamations of epistemological authorities….” (23). To assume that conspiracy theories are wrong is, in Uscinski’s view, to prejudice one’s research program. But this too depends on what that research program is. If it is to show what contributes to people coming to believe theories that are largely untethered from evidence about small groups of individuals acting in secret to undermine the common good and benefit their own interest, then it doesn’t appear to undermine it at all. This research program just defines the goals differently.

In discussing conspiracy theories Uscinski does bring up many of the usual ones–the 9/11 conspiracy theories, the various Kennedy assassination theories, the flat earth theory, as well as the Reptilian conspiracy theory. The latter is a long-time conspiracy theory that alien lizard people have intermingled with humans are secretly at the helms of power internationally, running human societies.

But along with these he also characterizes as conspiracy theories the views that Trump collaborated with the Russians in his 2016 election, as well as the views of Bernie Sanders and Paul Krugman that the one-percenters are involved in rigging the political system in the United States for their own benefit. These latter characterizations align with one of Uscinski’s other goals–to call into question the traditional assumption of a lot of those working on conspiracy theories that the Right-wing in the US is more prone to conspiracy theories that the Left-wing.

Uscinski attempts a kind of leveling. He wants to rid the term “conspiracy theory” of its negative connotation. And when it comes to politics in the US framework, he wants a “balanced approach” that “shows that Republicans and Democrats display nearly equal levels of conspiracy thinking” (97). The problem that occurs as he attempts the former is that he is pushing against the common language use of the term that is extremely negatively loaded. In reality, it is impossible for an academic book like Uscinski’s to change common language use. Even various authors he references, like Karl Popper, also use the term differently than Uscinski does. So treating the concept neutrally in a book that references so many others who use the term pejoratively proves somewhat tenuous.

Given the prevailing pejorative view of conspiracy theories, there is perhaps no completely satisfactory solution to how to refer to a distinction between the theories of conspiracies that is neutral and Conspiracy Theories that are not. But given common language usage, it seems some distinction is needed between the extremely low evidence (or absolutely absurd) theories and those that meet a higher evidence threshold.

For these purposes, we might try distinguishing between conspiracy theories or theories of conspiracies. Quassim Cassam, in his Conspiracy Theories (THINK)[image error], opts for this strategy. He speaks of the zany “Conspiracy Theories” using capital letters and reserves the small cased spelling “conspiracy theories” for less zany variants. As little satisfying as that may be, I don’t see any way to get around something like this if we intend to honor the common language use of the term and avoid certain problems that come with conflating the two (some of which I mention below). Maybe a concerted effort to refer to the latter as theories of conspiracies would be helpful. In any case, I will adopt Cassam’s usage as I continue in this post.

Another concern of the book is that Uscinski has an overly simplistic epistemological view of when we should even characterize a view as a conspiracy theory rather than a conspiracy fact. It is a theory until “deemed true by the appropriate epistemological authorities” (41). This correlates with his view that the conspiracy facts are distinguished from conspiracy theories by their adherence to “settled science” (95).

The problem is that even “settled science,” especially in fields like history or the social sciences, are rarely settled once and for all. In fact, it is difficult to maintain a hard and fast distinction between the theories and the facts. Evidence emerges over time and social scientists and historians revise their views of what the best theory is in light of newly emergent evidence. They are generally dealing with theories — more or less well-established.

In this, they are often engaged in what Charles Sanders Pierce has called the process of abduction, reasoning to the best explanation. That best explanation depends on what evidence is available and what models of explanation have emerged with which to explain them. In line with Pierce’s view, “settled science” is rarely so settled. We fixate our beliefs as long as no better theory, accompanied by better evidence, is available (“The Fixation of Belief,” 1877). Karl Popper’s view of falsification builds on this. His complementary approach is that we don’t know that our ideas are true; and we hold them undogmatically until better evidence comes along. Uscinski would clearly benefit from more consideration of such epistemic issues.

Where Uscinski does touch on the topic of the differing evidence for different conspiracy theories, he abandons it in short order. “It would be useful to have a uniform standard for separating the zany conspiracy theories from those more likely to be true. Unfortunately, there is no accepted method for doing so” (28). In fact, Uscinski appears to long for a “uniform standard” that is better than the one social sciences and history have for any subject. We simply have no choice but to weigh theories in light of the best evidence available (however vague that is), and, if we are rational, to make a decision based on that. These ideas are developed by Karl Popper in Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge (1963).* This result may indeed be a bit fuzzy. But in many cases, it is enough to allow us to differentiate the zany from the plausible from the probably true.

Uscinski continues his above quote as follows: “Withholding belief from conspiracy theories is therefore the most consistent strategy, because believing some conspiracy theories but rejecting others would almost certainly rely on inconsistent evidentiary standards.” In contrast to Uscinski, I think, in fact, that the best answer to whether we should believe in a theory about a conspiracy is, it depends.

There is a wildly different amount of evidence available for the myriad of theories of conspiracies that Uscinski outlines. Take the contrast between the Reptilian Conspiracy Theory and the theory that the Trump campaign colluded with the Russians to subvert the 2016 election. It may still well be that I don’t have enough evidence to warrant belief that the Trump campaign in fact engaged in such a conspiracy. But it may be that some who are more privy to the entire Mueller investigation and other investigations do have enough evidence for that. In any case, there is a reason to take the latter theory seriously as possibly true and to reject the Reptilian Conspiracy Theory as obviously false. This doesn’t depend on inconsistent evidentiary standards.

Here a reference to the idea of “warranted assertability” from the pragmatist philosopher, John Dewey, may be helpful. Dewey, like Pierce, highlighted the tentative character of our truth claims and underlined the need to move away from the idea that we discovered, as we might say, Truth with a capital T rather than “truth” with a small-cased one. His concern, like Pierce’s, was that we abandon dogmatism and be willing to revise our views and theories in light of the best available evidence. In light of that, he goes so far as to say, “There is no belief so settled as not to be exposed to further inquiry” (LTI, LW12: 16).

But he doesn’t mean by this that any type of questioning as we get from Conspiracy Theorists (note the caps) is advised. Rather, the evolving standards of the sciences and humanities provide us with some measures for distinguishing reasonable from unreasonable questions, good from bad evidence, and so on. Here, the key is that we follow an evidence-based procedure in generating our views. Many of those looking into Russia’s collusion are doing that. None of those proposing the Reptilian Conspiracy Theory are.

The origin of so many zany Conspiracy Theories and the lack of adherence to any strict evidentiary standards shows them to be unworthy of belief. And precisely the adherence of some theories of conspiracy to such standards of evidence shows them to be more reasonable. How much evidence is enough evidence and what kind of evidence is the right kind? This will remain somewhat vague, but no more so than cases in court often are. We have good reason for rejecting Uscinski’s treatment of all these conspiracy theories that are not shown to be supported by “epistemological authorities” as on equal footing.

So far, we have highlighted two primary weaknesses in Uscinski’s book. The first is in conflating all types of “conspiracy theories” and trying to force a non-pejorative definition onto a term that in its broad cultural use is heavily pejoratively loaded. The second is in failing to provide a more sophisticated account of evidentiary standards for such theories.

This leads to a third issue having unfortunate repercussions for his book–namely the potential for severe ideological misuse of the theory. The same kind of problem that arises from treating the Reptilian Conspiracy Theory and the view of Trump’s Russia collusion as essentially on par with one another appears again as Uscinski argues that the Right and the Left in the US are equally susceptible to Conspiracy Theories. The examples he provides do not show parity in reasonableness. Nor do his examples begin to consider the possible moral harms of the theories.

One problem with Uscinski’s attempt to neutralize the term “Conspiracy Theory” is that the general reading public is likely to misread him. If an author uses a term one way and the general public tends to use it in another way, this creates something of an amphiboly. An amphiboly is a logical fallacy where a term is used with two different meanings. So where Uscinski says the Reptilian Conspiracy Theory and the theory that Trump engaged in collusion with the Russians are both conspiracy theories, people are apt to read that they are both zany ungrounded Conspiracy Theories. They can both be equally disregarded as outlandish.

Similarly, when he says that Bernie Sanders and Paul Krugman are both conspiracy theorists, then readers, the vast majority of whom understand the idea of conspiracy theory pejoratively, are apt to feel that it’s safe to dump all of these together as utter nonsense. His lack of any thoughtful distinction on the varying possible evidentiary standards only exacerbates the problem. Both make his view rife for abuse as ideology. Readers, and perhaps Uscinski himself, may feel there is equal reason to disregard what Bernie Sanders says about the 1% and the Reptilian Conspiracy Theory and the allegations of Trump’s collusion. But this is deeply mistaken.