John G. Messerly's Blog, page 48

May 18, 2020

Philosophy cannot resolve the question ‘How should we live?’

The question How should we live? is one that many ask in a crisis, jolted out of normal patterns of life. But that question is not always a simple request for a straightforward answer, as if we could somehow read off the ‘correct’ answer from the world.

This sort of question can be like a pain that requires a response that soothes as much as it resolves. It is not obvious that academic philosophy can address such a question adequately. As the Australian philosopher Raimond Gaita has suggested, such a question emerges from deep within us all, from our humanity, and, as such, we share a common calling in coming to an answer. Academia often misses the point here, ignoring the depth, and responding as if problems about the meaning of life were logical puzzles, to be dissolved or dismissed as not real problems, or solved in a single way for all time. True, at various times philosophers such as Gilbert Ryle and more recently Mikel Burley have called for a revision of academia’s approach towards these sorts of questions, for a ‘thickened’ or expanded conception. But, while improving our awareness of their complexity and diversity, such approaches still fail to address the depth that their human origin provides.

The presence of a humanness, or a depth, to these sorts of questions comes not just from the context in which they’re asked, but also from their origin, their speaker. They are real questions for real people, and shouldn’t be dismissed with a logical flourish or treated like an interesting topic for a seminar. I would laugh if I heard a computer ask How should we live? after beating it at chess, but I would cry to hear a wife ask her husband, on the death of their son, How should we live? Although the same words have been uttered, these questions have a different form: the mother’s question contains a qualitative depth, a humanness that isn’t there in the computer’s question. We must acknowledge this if we want to find an answer to the specific question she asked with such poignancy.

The computer is a thing that cannot meaningfully ask those sorts of questions; in contrast, it’s offensive to call a person a ‘thing’. Only a human can ask that sort of question within this sort of context. We would hear the mother’s words and say that they contain a depth that’s revealing something perhaps previously hidden about herself; the computer’s question isn’t even said to be shallow. It seems to have nothing of that sort to reveal about itself whatsoever, like a parrot repeating the words it has been taught without the complexity of the human context that gives them their usual meaning. This isn’t to say that computers won’t one day be intelligent, ‘conscious’ or ‘sentient’, or that human language is ‘private’; it’s closer to the Wittgensteinian remark that: ‘If a lion could talk, we could not understand him.’

This means that the form that a language takes reflects the complex social context of the life of the speaker, and the degree to which I share a similar form of life with the speaker is the same degree to which I can meaningfully understand the utterance. The ‘life’ of the computer, we suppose, is either one-dimensional due to it lacking depth or, even if it has depth, it would be uncommunicable through human language, because, simply put, we and they differ so much. The humanness that provides the depth to our language is simply inaccessible to silicon chips and copper wires, and vice versa.

This depth to the human condition is part of what we mean when we speak of our humanity, spirit or soul, and anyone who wishes to question or explore this aspect of the human condition must do so in a form of language that can access and replicate its depth. We call those sorts of languages spiritual. But this way of speaking shouldn’t be taken literally. It doesn’t mean that spirits, souls and God exist, or that we must believe in their literal existence in order to use this sort of language.

Questions about the meaning of life and others of a similar kind are often misconstrued by those too ready to think of them as straightforward requests for an objective true answer.

Consider, for example, what atheists mean by ‘soul’ when they refute the cognitive proposition that asserts the literal existence of souls, in comparison with what I mean when I describe slavery as soul-destroying. If atheists were to argue that slavery cannot be soul-destroying because souls don’t exist, then I would say that there’s a meaning here that’s lost on them by being overly literal. If the statement ‘Slavery is soul-destroying’ is forced into a purely cognitive form, then not only does it misrepresent what I mean to say, it actively prevents me from ever saying it. I want to express something that represents the depth of the sort of experience I’m having: this isn’t a matter of making an implied statement about whether or not souls exist – it’s not affected by the literal existence or non-existence of souls. This sort of meaning to spiritual language is found at a different dimension to where cognitivists look, irrespective of their atheism, and this is achieved through our capacity to embed a dimension of depth to the form of our language through the non-cognitive process of expressing, describing and evoking our sense of humanity within one another.

When considering how to answer the question How should we live?, we should first reflect on how it is being asked – is it a cognitive question looking for a literal matter-of-fact answer, or is it also in part a non-cognitive spiritual remark in answer to a particular human, and particularly human, situation? This question, so often asked by us in times of crisis and despair, or love and joy, expresses and indeed defines our sense of humanity.

______________________________________________________________________

by Dave Ellis – This article was originally published at Aeon and has been republished under Creative Commons.

May 15, 2020

Critical Thinking & COVID-19: Argument from Authoritarianism

“Critical Thinking & COVID-19: Argument from Authoritarian”

by Professor Michael LaBossiere (Reprinted with permission)

While it would be irrational to reject medical claims of health care experts in favor of those made by President Trump, there are those who do just that. Considerations of why people do this is mainly a matter of psychology, but the likely errors in reasoning are a matter for philosophy.

While those who accept Trump as a medical authority are falling victim to a fallacious appeal to authority, it is worth considering the specific version of the fallacy being committed. I am calling this fallacy the argument from authoritarian. The error occurs when a person believes a claim simply because it is made by the authoritarian leader they accept. It has this form:

Premise 1: Authoritarian leader L makes claim c.

Conclusion: Claim C is true.

The fact that an authoritarian leader makes a claim does not provide evidence or a logical reason that supports the claim. It also does not disprove the claim—accepting or rejecting a claim because it comes from an authoritarian would both be errors. The authoritarian could be right about the claim but, as with any fallacy, the error lies in the reasoning.

The use of my usual silly math example illustrates why this is bad logic:

Premise 1: The dear leader claims that 2+2 =7.

Conclusion: The dear leader is right.

At this point, you might be thinking about the consequences someone might suffer from not accepting what an authoritarian leader claims—they could be fired, tortured, or even killed. While that is true, there is a critical distinction between having a rational reason to accept a claim as true and having a pragmatic reason to accept a claim as true or at least pretend to do so. Fear of retaliation by an authoritarian can provide a practical reason to go along with them but this does not provide evidence.

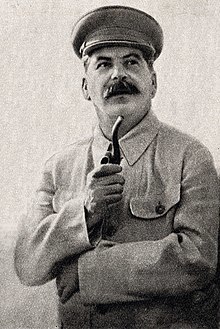

No matter how brutally an authoritarian enforces their view that 2+2=7 and no matter how many people echo his words, 2+2=4. While fear can provide people with a motivation to accept an argument from authoritarian, there are other psychological reasons driving the bad logic. This takes us to a simplified look at the authoritarian leader type and the authoritarian follower type. The same person can have qualities of both, and everyone has at least some of these traits—the degree to which a person has them is what matters.

An authoritarian leader type is characterized by the belief that they have a special status as a leader. At the greatest extreme, the authoritarian leader believes that they are the voice of their followers and that they alone can lead. Or, as Trump put it, “I alone can fix it.” Underlying this is the belief that they possess exceptional skills, knowledge, and ability that exceed those of others. As Socrates found out, people think they know far more than they do—but the authoritarian leader takes this to extremes and overestimates their abilities. This, as would be expected, leads them to make false claims and mistakes.

Since the authoritarian leader is extremely reluctant to admit their errors and limits, they must be dishonest to the degree they are not delusional and delusional to the degree they are not dishonest. Trump exemplifies this with his constant barrage of untruths and incessant bragging.

Because of the need to maintain the lies and delusions about their greatness and success, the authoritarian leader is intolerant of criticism, dissent, and competition. To the extent they can do so, they use coercion against those who would disagree and resort to insults when they cannot intimidate. Because the facts, logic, and science would tell against them, they tend to oppose all these things and form many of their beliefs based on their feelings, biases, and bad logic. They encourage their followers to do the same—in fact, they would not have true followers if no one followed their lead here. This describes Trump quite accurately.

While an authoritarian leader might have some degree of competence, their grotesque overestimation of their abilities and their fear of competent competition even among those who serve them will result in regular and often disastrous failures. Trump’s handling of COVID-19 provides an example of this. Maintaining their delusions and lies in the face of failure requires explaining it away. One approach is denial—to ignore reality, something Trump has been doing.

A second approach is to blame others—the leader is not at fault, because someone else is responsible. Trump has done this is well. One method here is scapegoating—finding someone else to bear undeserved blame for the leader’s failings. Trump has blamed Obama, the Democrats, the media, and the WHO for his failings. For the authoritarian, there is something of a paradox here. They must affirm their special greatness at the same time they are blaming vastly inferior foes who somehow manage to thwart them. These opponents must be both pathetic and exceptionally dangerous, stupid and brilliant, incompetent and effective, and so on for a host of inconsistent qualities.

An authoritarian leader obviously desires followers and fortunately for them, there are those of the authoritarian follower type. While opportunists often make use of authoritarian leaders and assist them, they are not believers. The authoritarian follower believes that their leader is special, that the leader alone can fix things. Thus, the followers must buy into the leaders’ delusions and lies, convincing themselves despite the evidence to the contrary. Trump’s supporters incorrectly believe him to be honest and competent. Some believe his untruths about COVID-19. And this is very dangerous.

Since the leader will tend to fail often, the followers must accept the explanations put forth to account for them. This requires rejecting facts and logic. The followers embrace lies and conspiracy theories—whatever supports the narrative of their leader’s greatness. Those who do not agree with the leader are not merely wrong, but as enemies of the leader—and thus enemies of the followers. The claims of those who disagree are rejected out of hand, and often with hostility and insults. Thus, the followers tend to isolate themselves epistemically—which is a fancy way of saying that nothing that goes against their view of the leader ever gets in. This motivates a range of fallacies including what I call an accusation of hate.

When I have attempted to discuss COVID-19 with Trump supporters, it almost always ends with them accusing me of hating Trump and their rejection of whatever claim I make that is not consistent with what Trump claims. I do think they are being sincere—like everyone, they tend to believe and reject claims based on how they feel about the source. Since they like Trump, they believe him in the face of all evidence. This is fallacious reasoning. Since I disagree with Trump’s false claims, it must follow that I hate Trump—otherwise I would just believe his untruths. It also follows, at least to them, that I am wrong. While this makes psychological sense, it is obviously bad logic and can be presented as a fallacy—the accusation of hate. It has this form:

Premise 1: Person A rejects Person B’s claim C.

Premise 2: Person A is accused of hating B.

Conclusion: Claim C is true.

As my usual silly math example shows, this is bad logic:

Premise 1: Dave rejects Adolph’s claim that 2+2=7.

Premise 2: Dave hates Adolph.

Conclusion: So, 2+2=7.

While hating someone would be a biasing factor, this does not disprove the alleged hater’s claim. It can have great psychological force—people tend to reject claims made by those they think hate someone they like. This is especially true in the case of authoritarian followers defending their leader.

Since authoritarian leaders are generally delusional liars who fail often, deny their failures and scapegoat others, they are extremely dangerous. The more power they have, the more harm they can do. They are enabled by their followers, which makes them dangerous as well. In a democracy, such as it is, the solution is to vote out the authoritarian and get a leader who does not exist in a swamp of lies and delusions. Until then, non-authoritarian leaders must step up to make rational decisions based on truth and good science—otherwise, the pandemic will drive America into ruin while lies and delusions are spun.

May 13, 2020

Everything Is Meaningless – But That’s Okay

(Originally published at 3 Quarks Daily. Reprinted by permission.)

by Charlie Huenemann

What would it be for life to have a “meaning”? What does it mean when people say life is meaningful? I’m not sure, so let’s start with smaller, more obviously meaningful things. Better yet, let’s start with some meaningless things.

When Bob sits down to polish the steel junk he’s about to haul to the scrap heap, we can say his activity is meaningless: there’s no point to it. Similarly, when my students sit down to prepare for an exam that I have decided to cancel, their work is pointless and meaningless. When Sally writes a memo about the futility of writing memos, crafting her prose to limpid perfection, with the aim of deleting her anti-memo memo before anyone reads it, we should feel some degree of concern for her mental well-being. Meaningless things have no point to them – nothing is achieved, no purpose can be fathomed, and the work we dedicate to them is entirely wasted. Meaningful things, let’s presume, are just the opposite.

So, how about life as a whole – your whole life, and the lives of everyone? If we believe in a Grand Scheme of Things, some cosmic contest with an unambiguous finish line, then we might then see lives as meaningful. The history of philosophy is crammed full of such Grand Schemes, but we might call upon Leibniz to present one of the greatest ones. This world, said Leibniz, is the best of all possible worlds, the very best world a just and omniscient being could call into existence, and it is made the best by all of the things people do, when taken as a whole. All finite things strive toward greater and greater perfections of being, and the world over time turns into something that is worthy of divine selection. If we embrace the Leibnizian scheme, we feel the pressure of bringing all our actions and thoughts to the highest reaches of moral and metaphysical perfection.

Everything is meaningful because everything contributes to the end God set for creation.

This is one thrillingly grand notion of cosmic meaningfulness – but hardly anyone now believes it. Most of us accept that the universe has not come about for the purpose of achieving anything. Cosmologists tell us that it’s something of a puzzle why there should be anything at all, and many of them are driven to the conclusion that there must be an infinity of possible universes, most of them boring beyond any description and a scant few of them including such noteworthy features as matter. They come to this conclusion precisely to avoid the conclusion our universe has anything to brag about. Our universe is the way it is because some universe had to be, and it’s consequently no surprise that we – as evolved, intelligent beings – would find ourselves in one of those rare universes in which something relatively interesting has happened.

What does our universe try to achieve? Well, if anything, it seems to enjoy growing entropy

– that is, it tries to shed itself of any order. Our universe would love nothing more than to become a thin, bland soup, and verdicts seem to go back and forth about whether it’s likely to succeed in this modest goal. The more fundamental point, of course, is that the universe itself does not really care one way or another about its own success. It just does whatever its laws tell it to do, and the laws, so far as we comprehend them, do not aim toward any special, purposeful end.

This tells us in the most straightforward way possible that all of existence is meaningless: everything has no point. “But hold on!” I hear you object. “That the universe doesn’t care should not mean that our lives are meaningless! Human lives are made meaningful by the hopes and aspirations of the people living them. We create our own meaning, with the ends we set and the decisions we make. You and I may have different values, of course, and we can enter into philosophical dialogue about them – but our dialogue presumes that lives can be meaningful, and indeed that there may be better and worse meanings to choose for our lives.”

While this is a cheery idea, I think it is completely false, even obviously false. I’ll grant, of course, that we can pretend that our lives are meaningful, and we can ginny up some enthusiasm for the purposes we imagine for our lives. But when we do this, we have to forget for the time being that (to repeat) all of existence is completely meaningless. We have to think that, somehow, that fact that we happen to value something is itself a meaningful fact – when it isn’t.

This is a core fact about the meaning of meaningfulness: in order for an activity or pursuit to be meaningful, it can’t be a matter of pretending. Bob might pretend that the scraps of metal he is polishing will be widely appreciated for their beauty, or that they will be given as medals to valiant soldiers. But this does not make his polishing meaningful; it is only an illusion that helps him to keep up his pointless efforts. Leibniz’s Grand Scheme, by contrast, makes everything meaningful because, if he were right, everything really would be contributing toward a real and meaningful end. Leibniz may have been wrong, but at least he didn’t have to pretend.

“But I’m not pretending,” you might insist. “I am choosing to regard my pursuit as meaningful, and declaring it to be so!” Notice, however, that one could make this declaration about any pursuit whatsoever – polishing scraps of metal, saving the lives of children, creating monuments, eating monuments, counting blades of grass, and so on. That’s exactly where the attempt to “create” meaning fails. If anything can be made meaningful by an individual’s choice – then nothing really is meaningful. It is only a matter of individuals acting as if or pretending that their pursuits are meaningful.

“But, in fact, some pursuits are better than others. Obviously, it is more meaningful to save lives, create art, and extend knowledge than it is to count blades of grass!” But this is not at all obvious. It may seem obvious – but only if we forget about the larger frame of futility that encompasses all human endeavors. The people whose lives we save today: all will die later on, as will everyone who remembers them. The species we save: it will someday go extinct, as will every species. We forge friendships and loving relationships that history will easily forget within a generation or two. We create great works of art that will inevitably be ground down by our universe’s drift toward entropy. For a mind-bogglingly huge chunk of time, the universe had no conscious beings in it; and the universe will soon return to that state, or an even less interesting one, for another mind-bogglingly huge chunk of time. Anything we can possibly think of or manage to do or love will be swallowed up in those twin enormities like a crayon pitched into the Grand Canyon.

If this talk of deep time seems too remote, consider the question that gets raised from time to time over a glass of wine: “What would you do today if you knew the world was going to end tomorrow?” Most people would toss aside everything they have been doing because the very pointlessness of it all becomes starkly evident. Even doctors might take their last day off, once they realize that, despite their best efforts, their patients will die tomorrow anyway. Well, here’s a newsflash: the world will end, maybe not tomorrow, but someday. With what reason should the distance between “tomorrow” and “someday” magically bestow meaningfulness upon the things we do?

When we claim that we make our own lives meaningful, we are investing in a shady distinction between short-term futility and long-term futility. Short-term futility, we all agree, is bad, meaningless, absurd: there’s no point in rushing to paint the house when the tornado is on its way. We try to avoid putting time or effort into projects that are evidently and immediately futile. But then we go on to think that it is meaningful to save the rainforest since the extinction of life on earth will not happen any time soon – its futility is long-term. But long-term futility is every bit as futile as short-term futility. Isn’t it obvious that, in the fullness of time, everything we do is futile – but because of the shortness of our lives and the small scope of our horizons, we manage to forget this fact and dupe ourselves into thinking otherwise?

So, no, we cannot “make” our lives meaningful by just ignoring the fact that everything sooner or later vanishes into a deep and dark hole of time. But let me hasten to add that, at the same time, I’m a huge fan of existing. (Woody Allen: “Cloquet hated reality but realized it was still the only place to get a good steak.”) I think there’s plenty of fun to be had – at least for those of us not in tragically dire circumstances. Moreover, siding with thinkers like Hume, I think there’s a great contentment in seeing other people being helped, and great joy in behaving like a decent human being. I would even call myself an optimist, since I’m willing to defend the view that humans have made genuine moral progress over the centuries, and I believe we’ll continue to do so. I’m a big fan of my species, for the most part.

Each one of our examples of meaningless activities can all be thoroughly enjoyed and appreciated. Bob might take great pleasure in revealing the beauty hidden within scraps of metal. My students might enjoy being together and arguing and exploring their knowledge together, even if the exam has been canceled. Sally may be in the highest throes of amusement as she drafts her anti-memo memo, intending to delete it as soon as she finishes. Recognizing these clearly pointless activities as meaningless need not make them any less enjoyable or rewarding. The great experiment of our age – living without Grand Schemes – consists in recognizing that we don’t need meaning in order to find value.

The distinction I’m invoking is this. A pursuit is made meaningful in virtue of being part of some larger purpose or end that exists apart from us. But a pursuit or activity or achievement can be pleasurable or valuable by meeting some condition set by us – either deliberately (as in staged contests), or simply by us being the sort of beings we are. We generally are the sort of beings who like having fun, seeing beautiful things, and helping one another. And that’s why we value these things – regardless of the fact that they are ultimately meaningless.

Now this distinction might prompt us to wonder whether we ought to find value in meaningless things. Whether we “ought” to or not, I can’t say. But I think we can’t help but do it. If some Eeyore (like me) comes along pointing out the long-term futility of all things, we should recognize that the things we have been valuing still feel really valuable to us, even considering the fact that everything and everyone will get sucked up into the deep, dark hole of time. Indeed, Eeyore’s prophecy might prompt us to see even greater value in the things we cherish – precisely because any lives we may touch will be with us for such a vanishingly small segment of time.

So we should not mistake our valuing of our pursuits for meaningfulness. The fact that humans, for a short slice of time, find fulfillment in doing nice or noble or beautiful things is simply another fact – a rather small one, really – within an entirely pointless existence. Isn’t that grand?

May 11, 2020

Critical Thinking & COVID-19: Trump’s “Expertise”

Critical Thinking & COVID-19: Trump’s “Expertise”

by Professor Michael LaBossiere. (Reprinted with permission)

Donald Trump was elected president and hence he has the legal authority conferred by this office. By having legal authority is not the same as having authority as an expert. In this essay, I will assess Trump’s authority as a medical expert.

It might seem unfair to judge Trump’s medical expertise—all previous American presidents would also fall short here. But this must be done because Trump regularly contradicts the claims of public health experts, including Dr. Fauci. One example was Trump’s somewhat ambiguous backing of chloroquine in which he both agrees and disagrees with Fauci’s concerns while also recommending that people try it, contrary to the advice of public health experts. In the early days of the crisis, Trump claimed, contrary to the experts, that COVID-19 was like the flu and suggested that it would probably disappear in April. Trump also asserted that the Democrat’s criticism of his handling of the virus was a hoax. Which was not true. Trump also asserted that extensive testing for the virus was not necessary for the United States to return to normal, which contradicts the view of medical experts.

Examples of Trump contradicting the experts and making untrue claims about the virus and his response to the pandemic could fill an entire report, but these should suffice to show why this must be done: the President is making claims that contradict the views of public health and medical experts and the American people need to choose between the two sources. In my previous essay, I made the case for why Dr. Fauci should be accepted as a credible expert and believed. But I also need to assess Trump using the same standards to see if he is a credible expert on public health issues. Spoiler alert: he is not.

The first standard is that the person must have sufficient expertise in the subject. While Trump did attend college, he has no formal education in public health. He has no experience in the area, beyond what is happening now. He has no accomplishments—only failures. His only reputation in this area is based on his handling of the crisis, which is objectively bad. While he is the president, this has no relevance to expertise in public health. Bizarrely, Trump claimed (on camera) that he has a “natural ability” in science because of his uncle. He even went so far as to brag about knowing so much about COVID-19 that CDC officials had to ask him about this special knowledge. I should not have to say that is not how expertise works.

To be fair, Trump has admitted that he is not a doctor and the President is neither required nor expected to be competent in public health—which is why previous presidents left such matters to actual experts.

Second, the claim must be in the person’s area of expertise. Trump is, has been established, not a public health expert. His supporters did argue that his alleged expertise in business (despite a deep history of failures) qualified him to be president. But does being a businessperson qualify a person as a public health expert? If it does, we should be turning to Jeff Bezos and other billionaires for our medical advice. Also, if this does hold true, then you should just go to a successful local business (such as a plumber) for your health care needs. So, even if Trump is the great businessperson that his supporters claim, this does not make him an expert in public health.

Third, there needs to be an adequate degree of agreement among the other experts in the field. As noted above, the experts disagree with Trump and agree with each other when it comes to many of his claims. As such, they should be accepted over him—especially since he is not an expert.

Fourth, the expert must not significantly biased. Trump is clearly biased—he has made it evident that his main concern is his re-election. When asked about allowing a cruise ship to disembark its passengers, his biggest worry was that it would impact his numbers. This is but one example of how he prefers untruths that he thinks help him to truths that help the county. As I noted in the previous essay, the fact that a person is biased does not entail that any specific claim they make is false—so to infer that a claim Trump makes is false because he is biased it would be to fall victim to an ad hominem. But his bias reduces his credibility.

Fifth, the area of expertise must be a legitimate area or discipline. Public health is certainly legitimate, but Trump is not in that field. Sixth, the authority must be identified. Well, we do know that Trump is saying what Trump says.

Finally, the expert needs to be honest and trustworthy. It has been established beyond all doubt that Trump is a chronic liar. His specific lies about the pandemic are being tracked by the Atlantic—a list that keeps growing. As I noted in the previous essay, the fact that a person is dishonest does not entail that any specific claim they make is false—so to infer that a claim Trump makes is false because he makes it would be to fall victim to an ad hominem. But his relentless lying destroys his credibility.

By applying these standards to Trump what is obvious is established by reason: if Trump and public health care experts disagree, the rational thing to do is believe the public health experts over Trump.

There are, of course, those that support Trump over the experts and have great (perhaps even absolute) faith in him. Speaking to these devoted supporters, I propose that you put your faith to the test. This will get dark, so consider this a trigger warning.

Imagine that you experience the following: “a headache that changes depending on the time of day and position of the head and gets worse over time, seizures and numbness.” You wisely decide to seek medical attention, for these are signs of a possible brain tumor. When you get to the doctor’s office, the receptionist says “you are in luck! Dr. Sanjay Gupta and President Trump are here and able to see you. Which one do you want to see?” If you believe that Trump should be trusted on public health over the medical experts, then you should choose to have Trump examine you—after all, you believe that he knows better than the medical experts. If you do not trust Trump about this and would trust Dr. Gupta, then you should trust the health experts over Trump when he contradicts them. Now, to get darker,

Suppose that you find out that you do have a brain tumor and the receptionist says “Sorry about that, but you are in luck because Dr. Gupta and President Trump are scrubbed up and ready to cut that tumor out of your head!” If you believe Trump over the medical experts in the case of COVID-19, then you accept that he is the best medical expert—so you should be happy to have him cut a hole in your head. If you are unwilling to let Trump do this, then you should not trust him over the medical experts when it comes to COVID-19.

While Trump is legally President, this does not make him a medical expert. When his claims contradict those of public health care experts, believe the experts. Believing Trump in such cases can put you and other people in danger.

May 6, 2020

The Stoics on Death (Walking Through a Cemetery)

(This is my 1000th post.)

(This is my 1000th post.)

I take regular walks through a cemetery in my neighborhood and recently noticed a new grave for a twelve-year boy who had been killed in a car accident. Coincidentally, on one of my walks, I encountered the parents of the young boy who were visiting the gravesite. I told them that I had passed the grave before and expressed my condolences. They thanked me. Still, the mother was inconsolable and her heartfelt weeping moved me.

Walking home I naturally thought about death, a topic about which I’ve often written about. Having recently read Brian Earp‘s essay, “Against Mourning,” I wondered if it could provide solace. Here is a brief summary of the piece.

The essay inquires into the extent to which we should grieve over the death of loved ones. The answer, according to the ancient Stoics, is that we shouldn’t grieve, at least not much. Instead, we should accept what we can’t change and move on. I suspect this sounds as cold to you as it does to me. Parents cry at the death of their child and why shouldn’t they?

The key here is the Stoic distinction between what we can and cannot control. Since we can’t change the fact, for instance, that a child has died we should accept it. But this seems crazy. In fact, failing to mourn long enough suggests psychological dysfunction and may even deserve condemnation.

Earp asks us to imagine a race of ‘Super-resilient’ people who are just like us but who don’t mourn when their loved ones die; they are super Stoics. But isn’t that grotesque? Doesn’t our moral intuition suggest that moving on too quickly is unseemly? For if you truly love someone isn’t it psychologically impossible to quickly move on? And if you don’t sufficiently lament their passing isn’t this a sign that you didn’t really love the deceased?

On the contrary, the Stoics claim it is possible to truly love someone and yet be relatively unmoved by their death, arguing that you can refrain from grieving for them if you have spent your life preparing for their death. But if you haven’t trained for your loved one’s deaths, writes Earp, then there probably is something wrong with you if you don’t grieve. In that case, perhaps you really didn’t love the deceased.

To be clear the Stoics didn’t maintain that we should “be unfeeling like a statue” as Epictetus said. We are social animals and we naturally love our family. So it is acceptable to experience some grief on the death of loved ones but much less than we usually suppose. It isn’t a matter of denying all feelings and emotions but to resist being controlled by them and thereby to determine what is appropriate. As Seneca said:

… Tears fall, even when we try to suppress them, and shedding them is a relief to the mind … Let’s allow them to fall, but not summon them up. Let what flows be what emotion forces from us, not what is required to imitate others. Let’s not add anything to our genuine mourning, increasing it to follow someone else’s example.

And here is Epictetus:

What you love … has been given to you for the present, not that it should not be taken from you, nor has it been given to you for all time, but as a fig is given to you or a bunch of grapes at the appointed season of the year. But if you wish for these things in winter, you are a fool. So if you wish for your son or friend when it is not allowed to you, you must know that you are wishing for a fig in winter.

But how do we train or prepare for the death of a child? For the Stoics, this is a matter of recognizing that even your little child will die. As Marcus Aurelius said: “In all your actions, words, and thoughts, be aware that it is possible that you—and by extension the ones you love most dearly—may depart from life at any time.” Or as Seneca wrote: “Let us continually think as much about our own mortality as about that of all those we love … Now is the time for you to reflect … Whatever can happen at any time can happen today.”

And from Epictetus:

… remind yourself that what you love is mortal … at the very moment you are taking joy in something, present yourself with the opposite impressions. What harm is it, just when you are kissing your little child, to say: Tomorrow you will die, or to your friend similarly: Tomorrow one of us will go away, and we shall not see one another any more?

Peter Adamson has called the above “the most chilling single passage in all of ancient philosophy.” But remember, argues Earp, “Epictetus is not counseling that we should take no joy in our children, much less that we should cultivate an attitude of cold indifference to protect ourselves emotionally in case they go before their time.” Instead, he is reminding us of the preciousness of the moment, reminding us to treat others well and to enjoy their companionship … now.

Stoics then grieve “as little as Nature will allow” because they have ridden themselves of false beliefs and prepared themselves for the inevitable. When the worst happens they cope well, not because they didn’t love, but because they prepared. We could say their love was richer than most because by reminding themselves love wouldn’t last they were able to more thoroughly relish the moment. They experience loss but also fondly recall the deep love they experienced. According to Seneca: “Let us see to it that the recollection of those whom we have lost becomes a pleasant memory to us.”

Nonetheless, can we really avoid despair when we lose someone we truly loved? “[T]here is a lot of empirical evidence that people do, as a matter of fact, ‘move on’ from even great personal losses much more quickly than they would predict.” Still, does this mean something is wrong with them for moving on too quickly?

On the contrary, “resilience to losing those we love plays a deep and systematic role in making us the kinds of creatures that can overcome the frequent and inevitable setbacks that we must suffer over a lifetime.” Adapting to loss may then be as much a part of our nature as the experience of grief. Our adaptive capacity explains “how someone could be willing to risk her life for her husband while failing to be significantly traumatized by his death … It just … [is]a remarkable trait of our species that caring very deeply about someone is compatible with a strongly muted reaction to their death.”

This is essentially the Stoic position.

Brief Reflections

On re-reading the article, I felt a disconnect between its academic tone and the subjective experience of grieving. It is easy to say that I should react stoically if my wife or one of my children or grandchildren died before me, but if that is strength, I’m weak. No doubt that’s what Descartes had in mind when he remarked,

But I confess there is need of prolonged discipline and frequently repeated meditation to accustom the mind to view all objects in this light; and I believe that in this chiefly consisted the secret of the power of such philosophers[The Stoics] as in former times were enabled to rise superior to the influence of fortune, and, amid suffering and poverty, enjoy a happiness which their gods might have envied.

Simply put, it is hard to be a practitioner of Stoicism.

Turning to another issue, I agree with Earp that remembering that we will die can spur us to treat others better. (Even if science eventually defeats death we should still treat each other better.) I also think that people often adapt to their circumstances, which is both good and bad. Good because it helps them endure, bad because they become complacent and don’t’ try to change things for the better—especially by making death optional.

Now Plato called philosophizing “practicing death.” If that’s true I’ve had a lot of practice. Still, thinking about death isn’t the same as experiencing it—a rehearsal isn’t the actual play. Analogously, words just don’t capture the experience.

However, walking through cemeteries is at least a bit of a rehearsal. I typically proceed slowly, looking at the tombstones and any available photos, and reading the epitaphs. I focus on the dates inscribed and relate them to my grandparents, parents, or children’s lives. I place the lives of the dead in a historical context. They were of my grandparents, parents, my own, or even my children’s generation. I’m not sure why I find it comforting to go there but by the time I return home, I tend to treat my wife better.

Walking through the cemetery also reminds me of how trivial my life is in the big scheme of things. All these people had their hopes, their dreams, their loves, their triumphs, their tragedies, and now, for them at least, that’s all gone. Mine will be too.

And when I encounter someone who has lost a loved one in the cemetery, which has happened on more than one occasion, I’m struck by the tragedy of life and death. The Stoics may help us cope, but it is a somewhat cruel world if adaptation is our best option.

Perhaps the young boy’s mother should have prepared better; perhaps she should have cried less; perhaps she should adapt quicker. But she has heartbroken, and I couldn’t blame her.

As I walked home I almost cried.

May 5, 2020

Critical Thinking & COVID-19: Argument from Authority

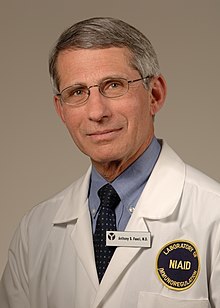

Dr. Anthony Fauci graduated first in his 1966 class at Cornell Medical College

Dr. Anthony Fauci graduated first in his 1966 class at Cornell Medical College

“Critical Thinking & COVID-19: Argument from Authority”

by Professor Michael LaBossiere (Reprinted with permission.)

There are many sources of information about the pandemic and not all of them are good or reliable. But accurate information is critical to your well being and even your survival. Unfortunately, not all sources are good and reliable. Some sources mean well but are unintentionally spreading misinformation. Other sources have malicious intent and are spreading disinformation. While being an expert on these matters is the best way to sort out which sources to trust, most of us are not experts in these areas. But we are not helpless. While we cannot become medical experts overnight, you can learn the basic skills for assessing sources and gain the ability to critically evaluate those who claim to have the truth.

When you accept a claim from a source because the source is supposed to be an authority, you are using an argument from authority. Despite its usefulness, it must be remembered that it is a relatively weak argument—you do not have direct evidence for the claim but are believing it because you think the source is credible. The gist of this reasoning is that you are accepting a claim because the source probably knows the truth and is probably telling the truth. Despite the inherent weakness in this argument, a true expert is more likely to be right than wrong when making considered claims within their area of expertise. While the argument is usually presented informally, it has the following structure:

Premise 1: A is (claimed to be) an authority on subject S.

Premise 2: A makes claim C about subject S.

Conclusion: Therefore, claim C is true.

An informal example would be to believe that you should not shake hands anymore because Dr. Anthony Fauci says you should not, and you trust his expertise. So how do you know when an authority really is an expert? Fortunately, there are clear standards that can be applied even if you know little or nothing about the claim being made. To the degree that the argument meets the standards, then it is reasonable to accept the conclusion. If the argument does not meet the standards it would be a fallacy (a mistake in logic) to accept the conclusion. It would also be a fallacy to reject the conclusion because the appeal to authority was fallacious.

First, the person must have sufficient expertise in the subject. A person’s expertise is determined by their relevant education (formal and otherwise), experience, accomplishments, reputation, and position. These should be carefully assessed to consider how much they establish expertise. For example, a person might occupy an impressive position because of family connections rather than ability or knowledge. The degree of expertise required varies from claim to claim. For example, someone who has completed college biology courses could be considered an expert when they claim that a virus replicates in living creatures by hijacking the cell mechanism. But a few college courses in biology would not make them an expert in epidemiology. Dr. Fauci is an excellent example of an expert on the pandemic.

Second, the claim must be in the person’s area of expertise. Expertise in one area does not automatically confer expertise in another. For example, being a world-renowned physicist does not automatically make a person an expert on morality or politics. Unfortunately, this is often overlooked or intentionally ignored. Actors and musicians, for example, are often accepted as experts in fields far outside their artistic expertise. Billionaires are also often wrongly regarded as experts in fields way outside their lanes. This does not mean that their claims outside their field are false, just that they lack the expertise to provide a good reason to accept the claim. Once again, Dr. Fauci is an excellent example here in the context of the pandemic.

Third, there needs to be an adequate degree of agreement among the other experts in the field. If there is not adequate agreement it would be a fallacy to appeal to the disputing experts. This is because for a claim made by one expert there will be a counterclaim by another qualified expert. In such cases appealing to the authorities would be futile.

That said, no field has complete agreement, so a certain degree of dispute is acceptable when using this argument. How much is acceptable is a matter of serious debate, but the gist is that the majority view of the qualified experts is the rational thing to believe. While they could turn out to be wrong, they are more likely to be right. In cases in which there is majority consensus non-experts sometimes pick the dissenting expert they agree with. This is not good reasoning; agreeing with an expert is not a logical reason to believe that the expert is right. Fortunately, the medical experts generally agree with each other about the key pandemic facts—though some disagreements do exist.

Fourth, the expert must not significantly biased. Examples of biasing factors include financial gain, political ideology, sexism, and racism. A person’s credibility is reduced to the degree that they are biased. While everyone has biases, this becomes a matter of concern when the bias is likely to unduly influence the person. For example, a doctor who owns a company that produces an anti-viral medication could be biased when making claims about the efficacy of the medication on COVID-19. Bias needs to be judged carefully and to reject a person’s claim because of bias can be a fallacy. After all, a person could resist their biases and even a biased person can be right. Going with the anti-viral example, to reject the doctor’s claim that it works because they can gain from its sale would be an ad hominem fallacy. While unbiased experts can be wrong, an unbiased expert is more credible than a biased expert—other factors being equal. Dr. Fauci serves as an excellent example here—he only seems biased in favor of keeping us healthy and alive.

Fifth, the area of expertise must be a legitimate area or discipline. While there can be a debate about what counts as a legitimate area, there are clear cut cases. For example, if someone claims to be an expert in magical healing crystals and recommends using quartz to ward off COVID-19, then it would be unwise to accept their claim. Using Dr. Fauci again, his field is clearly legitimate.

Sixth, the authority must be identified. If a person says a claim is true because an anonymous expert makes the claim, there is no way to tell if the person is a real expert. This does not make the claim false (to think otherwise would be a fallacy) but without the ability to assess the unnamed expert, you have no way to know if they are credible. In such cases, suspending judgment can be a rational option. As would be expected, unnamed experts are often used on social media so it is wise to be even more wary about such platforms. It is also wise to wary of false attributions—for example, someone might circulate false claims and attribute them to Dr. Fauci.

Finally, the expert needs to be honest and trustworthy. While being honest means that a person is saying what they think is true, it does not follow that they are correct. But an honest expert is more credible than a source that is inclined to dishonesty. But to infer that a dishonest source must be wrong would be an error. Dr. Fauci has an excellent reputation for honesty.

While these standards have been presented in terms of assessing individuals, the same standards apply to institutions and groups. For example, the CDC as an institution is a credible expert.

In terms of who to trust in the pandemic, the clear experts are Dr. Fauci, the CDC, and WHO. This is not to say that you should uncritically believe all their claims, but they are the best sources. As far as other sources, some are good while some are actively dangerous to believe.

May 3, 2020

Critical Thinking & COVID-19: Credibility

“Critical Thinking & COVID-19: Credibility” by Professor Michael LaBossiere.

(Reprinted with permission.)

While assessing the credibility of sources is always important, the pandemic has made this a matter of life and death. Those of us who are not epidemiologists or medical professionals must rely on others for our information. While some people are providing accurate information, there are well-meaning people unintentionally spreading unsupported or even untrue claims. There are also people knowingly and maliciously spreading disinformation. Your well-being and even survival depend on being able to determine which sources are credible and which are best avoided.

There are two types of credibility: rational and rhetorical. A bit oversimplified, rational credibility means that you should believe the source and rhetorical credibility means that you feel you should believe the source. The difference between the two rests on the difference between logical force and psychological force.

Logical force is objective and is a measure of how well the evidence/reasons given for a claim support that claim in terms of showing that it is true. When it comes to arguments, this is assessed in various ways ranging from applying the standards of an inductive argument to cranking out a truth table, to grinding through a proof. To the degree that a source has rational credibility, it is logical to accept the claims coming from that source.

Psychological force is subjective and is a measure of how much emotional influence something has on a person’s willingness to believe a claim. This is assessed in practical terms: how effective was it in persuading someone to accept the claim? While the logical force of an argument is independent of the audience, psychological force is audience dependent. What might persuade one person to accept a claim might enrage another into rejecting it with extreme prejudice. Political devotion provides an excellent example. If you present the same claim to Democrats and Republicans while saying that Trump said it, you will probably get very different reactions.

Psychological force provides no reason or evidence for a claim but is vastly more effective at persuading people than logical force. To use an analogy, the difference between the two is like the difference between junk food and kale. While junk food is tasty, it lacks nutritional value. While kale is good for you, it is not very appealing to most people. So, when people ask me how to “win” arguments, I always ask them what they mean by “win.” If they mean “provide proof that my claim is true”, then I say they should use logic. If they mean “get people to feel I am right, whether I am right or not”, then I say they should focus on the psychological force. As we will see in future essays, rhetoric and fallacies (bad logic) have far more psychological force than good logic.

The vulnerability of people to psychological force makes it exceptional dangerous during a pandemic—if people are assessing sources based on how they feel about the source, they are far more likely to accept disinformation and misinformation. This leads to acting on false beliefs and this can get people killed. The health and survival of people depend on being able to assess sources and this requires being able to neutralize (or at least reduce) the influence of psychological force. This is a hard thing to do, especially since the fear and desperate hope created by a pandemic makes people even more vulnerable to psychological force and less trusting of logical force. But it is my hope that this guide will provide some small assistance in doing this.

One step in weakening psychological force is being aware of the factors that are logically irrelevant but psychologically powerful. One set of factors consists of all the qualities that make people appealing and attractive but have no logical relevance to whether their claims are credible. One irrelevant factor is the appearance of confidence. A person who makes eye contact, has a firm handshake, is not sweating, and does not laugh nervously seems credible—which is why scammers and liars learn to behave this way.

But a little reflection shows that these are irrelevant to rational credibility. To use my usual silly math example, imagine someone saying “I used to think 2+2=4, but Billy looked me right in the eye and confidently said 2+2=12. So that has to be true.” Obviously, there are practical reasons to look confident when making claims, but confidence proves nothing. And lack of confidence disproves nothing. For example, “I used to think 2+2=4, but Billy seemed nervous and unsure when he said that 2+2=4. So, he must be wrong.”

Rhetorical credibility is also generated by qualities that might look for in a date or friend. These can include physical qualities such as height, weight, attractiveness, and style of dress. These also include age, ethnicity, and gender. But these are all logically irrelevant to rational credibility. To use the silly math example, if someone said, “Billy is tall, handsome, straight, wearing a suit, and white so when he says that 2+2=12, he must be right!” you know that would be stupid. Yet when people see a source that is appealing, they tend to believe them despite the irrelevance of the appeal. The defense is to ask yourself if you would still believe the claim if it was made by someone unappealing to you.

Rhetorical credibility also arises from good qualities that are still irrelevant to rational credibility. These include kindness, niceness, friendliness, sincerity, compassion, generosity, and so on for a range of virtues. While someone who is kind and compassionate will generally not lie, this does not entail that they are a credible source. For example, “Billy is so nice and kind and he says 2+2=12. I had my doubts at first, but how could someone so nice be wrong?” To use a less silly example, a very kind person might be very misinformed and pass on dangerous information about COVID-19 with the best of intentions. A defense is to ask yourself if you would still believe the claim if it was made by someone who had bad qualities. But what about honesty?

While it is tempting to see honesty as telling the truth, the more accurate definition is that an honest person says what they think is true. They could be honestly making a false claim. A dishonest person is willing to try to pass off as true what they think is untrue, but they could be wrong about it being untrue. And most dishonest people do not lie all the time. As such, while honesty does have some positive impact on rational credibility and dishonesty a negative impact, they are not decisive. But an honest source is generally preferable to a dishonest one.

In these polarized times, it is especially clear that group affiliation, ideology, and other values have a huge impact on how people judge rhetorical credibility. If a claim is made by someone on your side or matches your values, then you will tend to believe it. For example, Trump supporters will tend to believe what Trump says because Trump says it. If a claim is made by the other side or goes against your values, then you will tend to reject it. For example, anti-Trump folks will tend to doubt what Trump says. While affiliations and values lead people to engage in motivated “reasoning” it is possible to resist their siren lure and try to assess the rational credibility of a source.

One defense is to use my stupid math example as a guide: “Trump says that 2+2=12; Trump is my guy so he must be right!” Or “Trump says 2+2=4, but I hate him so he must be wrong.” Another defense is to try to imagine the claim being made by the other side or someone who has different values. For example, a Trump supporter could try imagining Obama or Clinton making the claims about Hydroxychloroquine that Trump makes. As a reverse example, Trump haters could try the same thing. This is obviously not a perfect defense but might help some. An excellent historical example of how ideology can provide rhetorical credibility is the case of Stalin and Lysenko—by appealing to ideology Lysenko made his false views the foundation of Soviet science. This provides a cautionary tale worth heading in these troubled times.

While this short guide tries to help people avoid falling victim to mere rhetorical credibility, standards are also needed to determine when you should probably trust a source—that is, standards for rational credibility. That is the subject of the next essay.

Stay safe.

May 1, 2020

“Critical Thinking & COVID-19: Assessing Claims”

“Critical Thinking & COVID-19: Assessing Claims” by Professor Michael LaBossiere.

(Reprinted with permission.)

Critical thinking can save your life, especially during a pandemic of viruses, disinformation, and misinformation. Laying aside all the academic jargon, critical thinking is the rational assessment of a claim in order to determine whether you should accept a claim as true, reject it as false, or suspend judgment about the claim. People often forget that they have the option to suspend judgment—in a time of misinformation and disinformation, this can sometimes be the best option.

Suppose that you see a post on Facebook claiming that drinking alcohol will reduce your chances of getting sick, you see a tweet about how gargling with bleach can kill the virus, or you hear President Trump extolling the virtues of hydroxychloroquine as a treatment for the virus. How can you rationally assess these claims if you are not a medical expert? Fortunately, critical thinking can help you here, even if you got most of your medical knowledge from watching Grey’s Anatomy.

When you get a claim that is worth assessing, the first step is to run it against your own observations and see if it matches them. If it does not, then this is a mark against it. If it does, that is a plus. Take the bleach claim as an example. If you go look at a bottle of bleach you will observe that it has clear safety warnings. While it will probably kill viruses it contacts, the warning label also indicates that it will also hurt you. Hence, the rational assessment of the claim that gargling bleach is a good way to protect yourself against the virus will reveal that this is not true. While your own observations are a good check on claims, they are obviously not infallible—so it is wise to critically consider their reliability. But do not gargle with bleach.

The second step, which usually happens automatically, is to test the claim against your background information. Your background information is all the stuff you have learned over the years. When you get a claim worth testing, you match it up against your background information to get a rough assessment of its initial plausibility—how likely it seems to be true on first consideration. This initial plausibility can obviously be adjusted as you investigate more. As an example, consider the claim about alcohol’s effect on the virus.

On the one hand, you probably learned that alcohol can be used to sterilize things—so that raises the plausibility of the claim. But you probably have not heard of people protecting themselves successfully from the flu or cold (which are also caused by viruses) by drinking alcohol. Also, you probably have in your background information the fact that the alcohol used to sterilize things is poisonous and that the alcohol you can safely drink is not used in this manner. So, the rational thing to do would be to take the claim about alcohol to be probably false.

One obvious problem here is that everyone’s background information is chock full of false beliefs. From my own experience, I know that I have believed many false things—so I infer I still believe false things. I just do not know which ones are false—if I did, I would stop believing them. Because of our fallibility, this method has a serious flaw: you could be accepting or rejecting a claim because of a false belief in your background information. This is why it is a good idea to assess your beliefs and weed out the bad ones—you can only be rationally confident of your assessment of a claim to the degree that you can be rationally confident that the background information you are using is correct. The more you know, the better you will be at making such assessments—so learning is a good thing.

While having false beliefs can cause errors in assessing claims, people are also impacted by biases and fallacies. Since there is a multitude of both, I will only briefly discuss a few that are especially relevant during this pandemic. People tend to be biased in favor of their group, be it their religion, political party, or sports team. This leads people to tend to believe claims made by members of their group, which fuels the groupthink fallacy: believing that a claim is true because someone in your group made the claim and you are proud of your group.

This can also be seen as a version of the appeal to belief fallacy in which one believes that a claim is true because their group believes that it is true. While the virus kills across party lines, the pandemic has become politicized. Because of this, people who have strong partisan feelings will tend to believe what their side says and disbelieve the other side—but this is bad logic. As such, making rational assessments in the pandemic (or anytime) requires taking the effort to set aside such biases and consider the claim as objectively as possible. This is a hard thing for some people to do, but your life depends on it in this time of misinformation and disinformation.

Since pandemics are terrifying and people want to have hope, it is also important to be on guard against the poor logic of appeal to fear/scare tactics and wishful thinking. An appeal to fear occurs when a person accepts a claim as true because of fear rather than having actual evidence or reasons to do so. Something that provides good reasons can be scary—but if the only “reason” to accept a claim is fear, then the fallacy is committed. To illustrate, the virus is scary because it can kill you. This does give you a good reason to take precautions against it—so reasoning that because it is deadly, you should be careful would not be an error. But if someone believes that bleach will protect them because they have been scared into accepting this, then they are a victim of the fallacy (and bleach). In addition to fear, there is also hope.

Wishful thinking is a classic fallacy in which a person believes a claim because they want it to be true (or reject a claim because they want it to be false). Since there is currently no vaccine or cure for the virus, it is natural for people to engage in wishful thinking—to believe claims simply because they want them to be true. For example, a person might think that they will not get sick from the virus out of wishful thinking—which can be very dangerous to themselves and others. As another example, a person might believe that drinking alcohol will protect them from the virus because they want it to be true; but this is not true.

The defense against wishful thinking is not to give up hope, but to not let false hope make you believe things without evidence. This can be hard to do—these are difficult times and objectively considering claims can lead to disappointment. But wishful thinking can get you and others killed—so keep hold of hope, but do not let false hope blind you. In the next essay, I will discuss how to assess experts and alleged experts.

April 30, 2020

“Critical Thinking & COVID-19: Straw Person, Steel Person, and Just Kidding”

“Critical Thinking & COVID-19: Straw Person, Steel Person, and Just Kidding”

by Professor Michael LaBossiere. (Reprinted with permission)

During a White House press briefing President Trump expressed interest in injecting disinfectants as a treatment for COVID-19. In response, medical experts and the manufacturers of Lysol warned the public against this. Trump’s defenders adopted two main strategies. The first was to interpret Trump’s statements in a favorable way; the second was to assert they were “fact-checking” the claim that Trump told people to inject disinfectant. Trump eventually claimed that he was being sarcastic to see what the reporters would do. From the standpoint of critical thinking, there is a great deal going on here involving rhetorical devices and fallacies. I will briefly go over how critical thinking can sort through this situation and how it can be used in analogous situations.

When interpreting or reconstructing claims and arguments made by others, philosophers are supposed to apply the principle of charity. Following this principle requires interpreting claims in the best possible light and reconstructing arguments to make them as strong as possible. There are three reasons to follow the principle. The first is that doing so is ethical. The second is that doing so avoids committing the straw person fallacy, which I will talk more about in a bit. The third is that if I am going to criticize a person’s claims or arguments, criticism of the best and strongest versions also takes care of the lesser versions.

The principle of charity must be tempered by the principle of plausibility: claims must be interpreted, and arguments reconstructed in a way that matches what is known about the source and in accord with the context. For example, reading quantum physics into the works of our good dead friend Plato would violate this principle.

Getting back to injecting disinfectants, it is important to accurately present Trump’s statements in context and to avoid making a straw person. The Straw Person fallacy is committed when one ignores a person’s actual claim or argument and substitutes a distorted, exaggerated or misrepresented version of it. This sort of “reasoning” has the following pattern:

Premise 1: Person A makes a claim or argument X.

Premise 2: Person B presents Y (which is a distorted version of X).

Premise 3: Person B attacks Y.

Conclusion: Therefore, X is false/incorrect/flawed.

This sort of “reasoning” is fallacious because attacking a distorted version of a claim or argument does not constitute a criticism of the position itself. This fallacy often makes use of hyperbole, a rhetorical device in which one makes an exaggerated claim. A Straw Person can be highly effective because people often do not know the real claim or argument being attacked. The fallacy is especially effective when the straw person matches the audience’s biases or stereotypes—they will feel that the distorted version is the real version and accept it.

While this fallacy is generally aimed at an audience, it can be self-inflicted: a person can unwittingly make a Straw Person out of a claim or argument. This can be done entirely in error (perhaps due to ignorance) or due to the influence of prejudices and biases.

The defense against a Straw Man, self-inflicted or not, is to take care to get a person’s claim or argument right and to apply the principle of charity and the principle of plausibility.

Some of Trump’s defenders have been claiming that Trump was the victim of a straw person attack; they are “fact-checking” and asserting that Trump did not tell people to drink bleach. Somewhat ironically, they might be engaged in Straw Person attacks when attempting to defend Trump from alleged Straw Person attacks—warning people to not drink bleach or inject disinfectants is not the same thing as claiming that Trump told people to drink bleach.

His defenders are right that Trump did not tell people to drink bleach. His exact words, from the official White House transcript, are as follows: “And then I see the disinfectant, where it knocks it out in a minute. One minute. And is there a way we can do something like that, by injection inside or almost a cleaning. Because you see it gets in the lungs and it does a tremendous number on the lungs. So it would be interesting to check that. So, that, you’re going to have to use medical doctors with. But it sounds—it sounds interesting to me.”

Trump does not, at any point, tell people to drink bleach—he does not even use those words. He does not even tell people to inject disinfectant. As such, the “Clorox Chewables” and similar memes can be seen as a form of visual Straw Person attack against Trump—they can also be seen as the rhetorical device of mockery. To avoid committing the Straw Person fallacy, we need to use Trump’s actual statements—so attacking him for advocating drinking bleach would be an error. Somewhat ironically, Trump’s actual statements are so terribly mistaken that they sound like a Straw Person.

While Trump does not directly tell people to inject disinfectants, he can be seen as engaging in a form of innuendo—a rhetorical technique in which something is suggested or implied without directly saying it. Anyone who understands the basics of how language and influence works would get that Trump’s remarks about injecting disinfectant would cause some people to believe that this was a good idea or at least lead them to think this was something worth considering. There is evidence for this in the form of calls to New York City poison control centers and similar calls in Maryland and other states. Although there have been some claims that people have been hospitalized because of misusing disinfectant, I have not seen adequate confirmation of these claims.

One main feature of innuendo is that it allows a person to deny they said what they implied or suggested—after all, they did not directly say it. Holding someone accountable requires having adequate evidence that they did intend what their words imply or suggest—this can be challenging since it requires insights into their character and motives. There is also an obvious moral issue here about the responsibility of influential people to take care in what they say—something that goes beyond critical thinking. Spoiler: the president needs to be careful in what he says.

Trump clearly uses words that convey the idea that he thinks medical doctors should test injecting disinfectants into peoples’ lungs as a possible treatment for COVID-19. This takes us back to my earlier discussion of experts and my case that Trump is not an expert. I should not have to say this, but injecting disinfectants into lungs would be extremely dangerous—something that almost anyone should know. Given Trump’s well-established record of dangerous ignorance, interpreting his words as meaning what they clearly state does meet the conditions of the principle of charity and the principle of plausibility: these are his exact words, in context and with full consideration of the source.

Some of Trump’s defenders have tried to use what I will call the Steel Person fallacy. The Steel Person fallacy involves ignoring a person’s claim or argument and substituting a better one in its place without justification. This sort of “reasoning” has the following pattern:

Premise 1: Person A makes claim or argument X.

Premise 2: Person B presents Y (which is a better version of X).

Premise 3: Person B defends Y.

Conclusion: Therefore, X is true/correct/good.

This sort of “reasoning” is fallacious because presenting and defending a better version of a claim or argument does not show that the actual version is good. A Steel Person can be highly effective because people often do not know the real claim or argument being defended. The fallacy is especially effective when the Steel Person matches the audience’s positive biases or stereotypes—they will feel that the improved version is the real version and accept it. The difference between applying the principle of charity and committing a Steel Person fallacy lies mainly in the intention: the principle of charity is aimed at being fair, the Steel Person fallacy is aimed at making a person’s claim or argument appear much better than it is and so is an attempt at deceit.

While this fallacy is generally aimed at an audience, it can also be self-inflicted: a person can unwittingly make a Steel Person out of a claim or argument. This can be done entirely in error (perhaps due to ignorance) or due to the influence of positive biases. The defense against a Steel Man, self-inflicted or not, is to take care to get a person’s claim or argument right and to apply the principle of plausibility.

In the case of Trump, he is clearly expressing interest in injecting disinfectants into the human body. Some of his defenders created a Steel Man version of his claims, contending that what he really was doing was presenting new information about using light, heat, and disinfectant killing the virus. To conclude that Trump was right because of this unjustified better version of his statements has been offered would be an error in logic. While light, heat, and disinfectant probably can destroy the virus, Trump’s claim is clearly about injecting disinfectant into the human body—which, while not telling people to drink bleach, is a dangerously wrong claim.

Trump himself undermined these defenders by saying “I was asking a question sarcastically to reporters like you just to see what would happen.” If this is true, then his defenders’ claims that he was not talking about injecting disinfectant would be false—he cannot both be saying something dangerously crazy to troll the press and be making a true and rational claim about cleaning surfaces. Trump seems to be attempting to use a rhetorical device popular with the right (although anyone can use it). This method could be called the “just kidding” technique and can be put in the meme terms “for the lulz.”

One version of the “just kidding” tactic occurs when a person says something that is racist, bigoted, sexist, or otherwise awful and does not get the positive response they expected or are called out and held accountable for what they said. The person’s “defense” is that they did not really mean what they said, they were “just kidding. “As a rhetorical technique, it is an evasive maneuver designed to avoid accountability. The defense against this tactic is to assess whether the person was plausibly kidding or not—that is, did they intend to be funny without malicious intent and fail badly or are they trying to weasel out of accountability for meaning what they said? This can be difficult to sort out since you need to have some insight into the person’s motives, character, and so on.

Another version of the “just kidding” tactic is somewhat similar to the “I meant to do that” tactic. When someone does something embarrassing or stupid, they will often try to reduce the humiliation by claiming they intended to do it. In Trump’s injection case, he is claiming that intended to say what he said and that he was being sarcastic—thus he meant to do it but was just kidding.

If Trump was just kidding, he thought it was a good idea to troll the media during a pandemic—which is a matter for ethics rather than critical thinking. If he was not kidding, then he was attempting to avoid accountability for his claims—which is the point of this tactic. The defense against this tactic is to assess whether the person was plausibly kidding or not—that is, did they really mean to do it and if what they meant to do was just kidding.

This requires having some insight into the person’s character and motives as well as considering the context. In the case of Trump, the video shows him addressing his remarks to the experts rather than the press and he seems completely serious. There is also the fact that a president engaged in a briefing on a pandemic should be serious rather than sarcastic. As such, he does not seem to be kidding. But Trump has put himself in a dilemma of awfulness: he was either seriously suggesting a dangerous and stupid idea to the nation or trying to troll the press during a briefing on a pandemic that is killing thousands of Americans. Either way, he is terrible.

April 29, 2020

Review of “Planet of the Humans”