John G. Messerly's Blog, page 56

November 19, 2019

Carl Sagan: A Universe Not Made For Us

Carl Sagan (1934–1996) is one of my intellectual heroes. I first encountered his work in 1980 watching the 13-part PBS mini-series “Cosmos.” While I had taken many college science courses before that, there was something special about his presentation that excited me, especially his poetic, philosophical monologues. (I’ve written before about the “pale blue dot,” “on human survival,” and “science as a candle in the dark.”)

Today I rewatched the moving video above. Below is a brief recap and the full text.

Sagan begins by noting how pre-scientific cosmologies arise from our early experience. But “then science came along and taught us that we are not the measure of all things.” But Sagan wants the truth science gives not illusory comfort of religion. And today we should no longer believe “that the Universe was made for us … We long to be here for a purpose, even though, despite much self-deception, none is evident.”

But this doesn’t have to lead to pessimism because “we find ourselves on the threshold of a vast and awesome Universe that utterly dwarfs—in time, in space, and in potential—the tidy anthropocentric proscenium of our ancestors.” There is no need then to regret that we weren’t placed in a garden made for us but in which we were supposed to remain ignorant. Instead, we can use our minds to discover what is really true about the universe and where we want to go in it.

What then is the meaning of our lives?

The significance of our lives and our fragile planet is then determined only by our own wisdom and courage. We are the custodians of life’s meaning. We long for a Parent to care for us, to forgive us our errors, to save us from our childish mistakes. But knowledge is preferable to ignorance. Better by far to embrace the hard truth than a reassuring fable.

If we crave some cosmic purpose, then let us find ourselves a worthy goal.

For those interested, here is the full text:

Our ancestors understood origins by extrapolating from their own experience. How else could they have done it? So the Universe was hatched from a cosmic egg, or conceived in the sexual congress of a mother god and a father god, or was a kind of product of the Creator’s workshop—perhaps the latest of many flawed attempts. And the Universe was not much bigger than we see, and not much older than our written or oral records, and nowhere very different from places that we know.

We’ve tended in our cosmologies to make things familiar. Despite all our best efforts, we’ve not been very inventive. In the West, Heaven is placid and fluffy, and Hell is like the inside of a volcano. In many stories, both realms are governed by dominance hierarchies headed by gods or devils. Monotheists talked about the king of kings. In every culture we imagined something like our own political system running the Universe. Few found the similarity suspicious.

Then science came along and taught us that we are not the measure of all things, that there are wonders unimagined, that the Universe is not obliged to conform to what we consider comfortable or plausible. We have learned something about the idiosyncratic nature of our common sense. Science has carried human self-consciousness to a higher level. This is surely a rite of passage, a step towards maturity. It contrasts starkly with the childishness and narcissism of our pre-Copernican notions.

And, again, if we’re not important, not central, not the apple of God’s eye, what is implied for our theologically based moral codes? The discovery of our true bearings in the Cosmos was resisted for so long and to such a degree that many traces of the debate remain, sometimes with the motives of the geocentrists laid bare.

What do we really want from philosophy and religion? Palliatives? Therapy? Comfort? Do we want reassuring fables or an understanding of our actual circumstances? Dismay that the Universe does not conform to our preferences seems childish. You might think that grown-ups would be ashamed to put such disappointments into print. The fashionable way of doing this is not to blame the Universe—which seems truly pointless—but rather to blame the means by which we know the Universe, namely science.

Science has taught us that, because we have a talent for deceiving ourselves, subjectivity may not freely reign.

Its conclusions derive from the interrogation of Nature, and are not in all cases predesigned to satisfy our wants.

We recognize that even revered religious leaders, the products of their time as we are of ours, may have made mistakes. Religions contradict one another on small matters, such as whether we should put on a hat or take one off on entering a house of worship, or whether we should eat beef and eschew pork or the other way around, all the way to the most central issues, such as whether there are no gods, one God, or many gods.

If you lived two or three millennia ago, there was no shame in holding that the Universe was made for us. It was an appealing thesis consistent with everything we knew; it was what the most learned among us taught without qualification. But we have found out much since then. Defending such a position today amounts to willful disregard of the evidence, and a flight from self-knowledge.

We long to be here for a purpose, even though, despite much self-deception, none is evident.

Our time is burdened under the cumulative weight of successive debunkings of our conceits: We’re Johnny-come-latelies. We live in the cosmic boondocks. We emerged from microbes and muck. Apes are our cousins. Our thoughts and feelings are not fully under our own control. There may be much smarter and very different beings elsewhere. And on top of all this, we’re making a mess of our planet and becoming a danger to ourselves.

The trapdoor beneath our feet swings open. We find ourselves in bottomless free fall. We are lost in a great darkness, and there’s no one to send out a search party. Given so harsh a reality, of course we’re tempted to shut our eyes and pretend that we’re safe and snug at home, that the fall is only a bad dream.

Once we overcome our fear of being tiny, we find ourselves on the threshold of a vast and awesome Universe that utterly dwarfs—in time, in space, and in potential—the tidy anthropocentric proscenium of our ancestors. We gaze across billions of light-years of space to view the Universe shortly after the Big Bang, and plumb the fine structure of matter. We peer down into the core of our planet, and the blazing interior of our star. We read the genetic language in which is written the diverse skills and propensities of every being on Earth. We uncover hidden chapters in the record of our own origins, and with some anguish better understand our nature and prospects. We invent and refine agriculture, without which almost all of us would starve to death. We create medicines and vaccines that save the lives of billions. We communicate at the speed of light, and whip around the Earth in an hour and a half. We have sent dozens of ships to more than seventy worlds, and four spacecraft to the stars.

To our ancestors there was much in Nature to be afraid of—lightning, storms, earthquakes, volcanos, plagues, drought, long winters. Religions arose in part as attempts to propitiate and control, if not much to understand, the disorderly aspect of Nature.

How much more satisfying had we been placed in a garden custom-made for us, its other occupants put there for us to use as we saw fit. There is a celebrated story in the Western tradition like this, except that not quite everything was there for us. There was one particular tree of which we were not to partake, a tree of knowledge. Knowledge and understanding and wisdom were forbidden to us in this story. We were to be kept ignorant. But we couldn’t help ourselves. We were starving for knowledge—created hungry, you might say. This was the origin of all our troubles. In particular, it is why we no longer live in a garden: We found out too much. So long as we were incurious and obedient, I imagine, we could console ourselves with our importance and centrality, and tell ourselves that we were the reason the Universe was made. As we began to indulge our curiosity, though, to explore, to learn how the Universe really is, we expelled ourselves from Eden. Angels with a flaming sword were set as sentries at the gates of Paradise to bar our return. The gardeners became exiles and wanderers. Occasionally we mourn that lost world, but that, it seems to me, is maudlin and sentimental. We could not happily have remained ignorant forever.

There is in this Universe much of what seems to be design.

But instead, we repeatedly discover that natural processes—collisional selection of worlds, say, or natural selection of gene pools, or even the convection pattern in a pot of boiling water—can extract order out of chaos, and deceive us into deducing purpose where there is none.

The significance of our lives and our fragile planet is then determined only by our own wisdom and courage. We are the custodians of life’s meaning. We long for a Parent to care for us, to forgive us our errors, to save us from our childish mistakes. But knowledge is preferable to ignorance. Better by far to embrace the hard truth than a reassuring fable.

If we crave some cosmic purpose, then let us find ourselves a worthy goal.

November 17, 2019

Countries Ranked on Press Freedom & Response to Climate Change

(This is an addendum to my previous post, “Best Countries to Live In.” I’ve added these two indexes and aggregated their scores with the ones I previously included in my best countries to live in.)

Dark blue = Good situation; Light blue = Satisfactory situation; Yellow = Noticeable problems; Orange = Difficult situation; Red = Very serious situation

The Press Freedom Index is an annual ranking of countries compiled and published by Reporters Without Borders based upon the organisation’s own assessment of the countries’ press freedom records in the previous year. It intends to reflect the degree of freedom that journalists, news organisations, and netizens have in each country, and the efforts made by authorities to respect this freedom. Having a free press to expose government corruption and ensure the free flow of ideas is obviously crucial to having a good socieity.

1. Norway 2. Finland 3. Sweden 4. Netherlands 5. Denmark

6. Switzerland 7. New Zealand 8. Jamaica 9. Belgium 10. Costa Rica

11. Estonia 12. Portugal 13. Germany 14. Iceland 15. Ireland

16. Austria 17. Luxembourg 18. Canada 19. Uruguay South 20. Suriname

21. Australia 22. American Somoa 23. Namibia 24. Latvia 25. Cape Verde

(The USA is 48th)

11) Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative

The ND-GAIN Country Index is a measurement tool that helps governments, businesses and communities examine risks exacerbated by climate change, such as over-crowding, food insecurity, inadequate infrastructure, and civil conflicts. Free and open source, the Country Index uses 20 years of data across 45 indicators to rank 181 countries annually based on their level of vulnerability, and their readiness to successfully implement adaptation solutions. An array of analytic tools allows users to examine trends, play out scenarios, and investigate components over time. This may be the most important index of all. Here is their 2019 list.

1.Norway 2. New Zealand 3. Finland 4. Sweden 5. Australia

6. Switzerland 7. Denmark 8. Austria 9. Germany 9. Iceland

9. Singapoer 12. UK 13. Canada 14. Luxembourg 15. USA

16. South Korea 17. France 18. Netherlands 19. Slovenia 20. Japan

21. Ireland 22. Czeck Republic 23. Poland 24. Spain 25. Estonia

(Note – I’ve added these two indexes and aggregated their scores with the ones I previously included in my best countries to live in. The revised rankings can be found there.)

November 15, 2019

Summary of the Sophists

Democritus (center) and Protagoras (right). 17th-century painting by Salvator Rosa.

Democritus (center) and Protagoras (right). 17th-century painting by Salvator Rosa.

© Darrell Arnold Ph.D.– (Reprinted with Permission)

https://darrellarnold.com/2019/08/15/...

(A recent post summarized the views of Protagoras, who is generally regarded as the first and most important Sophist. Here is a brief summary of some other Sophists.)

On various issues, the sophists were clearly not of one mind. Callicles and Hippias of Elis both disagreed with Protagoras about the primacy of convention over nature. Nature, they maintained, was primary. In fact, Callicles offers arguments that sound rather Nietzschen. The morals embodied in customs benefit those who are weak in society while holding back individuals who are by nature strong. According to natural justice, those who are strong should pursue their own interests and not be held back by social conventions.

The view of the primacy of nature over convention leads Hippias is a fully different direction. He seems to have believed that there are unwritten laws of nature that could trump social conventions. This also indicates the basis at least for a view that would rise above the relativism for which the sophists are known since appeals to this natural law could be used to adjudicate between conflicts of existing laws. His views on this may have been influenced by Heraclitus. The threat of appeals to such laws were in any case severe enough that an ordinance was passed in Athens in the fifth century BCE that forbad the reference to unwritten laws in court cases.

Critias, a friend of Socrates who some consider a sophist, has interesting ideas on the origin of our views of the gods that are echoed historically later by Hobbes, perhaps unwittingly. The gods, he argues, are fictions created by clever to prey on people’s fears and stop people from breaking moral conventions. Here, Critias apparently does not think of the gods as a product of the weak, as a thinker with Callicles orientation would, who want to impose social order on the strong, but rather as a product of the strong who want to impose rules on the weak. In contrast to Callicles, then, who sees the weak as benefiting from the laws, Critias sees the strong as benefiting from them.

Thrasymacus is most well-known for his view of justice. In the Republic, Plato has him making two contrary claims: 1) Justice is what is the good of the stronger. 2) Justice is the promotion of the good of another. For a weaker party in a transaction, these two might coincide, but for the stronger, they would not. He is not shown to reason so clearly about these issues. He shows greater clarity of thought on his own views of the existence of the gods. His argument points to what has come to be known as the problem of evil. Given the evil in the world, Thrasymachus argues we must conclude either that the gods do not exist or that they do not care about the affairs of men. He thinks the latter view more convincing (Waterfield, 270).

Thrasymacus, like many of the sophists, was articulating and perhaps exacerbating the religious and moral crisis in Athens. The old order of the gods, with the social and moral conventions that were tied into Greek natural theology, was breaking down. The sophists contributed to the breakdown of both the theology and the dominant moral views. Perhaps one reason they have been demonized over history is that they highlight weaknesses of their social order without offering strongly argued positions to replace them with. In addition, their thinking often appears to lack consistency. Plato and Aristotle will do a better job of developing systems of thought that address the religious and moral crisis in Athens. But various impulses of the sophists will continue to resonate with people throughout history and various ideas that they express in kernel form will eventually find better spokespeople.

November 12, 2019

This Is How We Know Christianity Is a Delusion

© Richard Carrier, Ph.D. (Reprinted with Permission)

© Richard Carrier, Ph.D. (Reprinted with Permission)

Richard Carrier is a world-renowned author and speaker. As a professional historian, published philosopher, and prominent defender of the American freethought movement, Dr. Carrier has appeared across the U.S., Canada and the U.K., and on American television and London radio, defending sound historical methods and the ethical worldview of secular naturalism. His books and articles have received international attention. With a Ph.D. from Columbia University in ancient history, he specializes in the intellectual history of Greece and Rome, particularly ancient philosophy, religion, and science, with emphasis on the origins of Christianity and the use and progress of science under the Roman empire. He is also a published expert in the modern philosophy of naturalism as a worldview.

He is the author of, among other works,

On the Historicity of Jesus,

Proving History,

Sense and Goodness without God,

The Scientist in the Early Roman Empire,

Science Education in the Early Roman Empire,

Not the Impossible Faith,

Why I Am Not a Christian,

Hitler Homer Bible Christ, and a contributor to

The Empty Tomb,

The Christian Delusion,

The End of Christianity, and

Christianity Is Not Great

I thank Dr. Carrier for allowing me to reprint his essay:

“This Is How We Know Christianity Is a Delusion.”

In researching another article I came across an old piece by Mark McIntyre. On his blog Attempts at Honesty, back in 2011, he wrote a brief piece dismissing New Atheism with the argument that “their unbelief is not due to the lack of evidence but the suppression of it.” The fact that this is disturbingly ironic is precisely the lesson we can learn from it: it’s not the atheists who are suppressing or ignoring evidence. It’s the likes of Mark McIntyre who are.

This is what a delusion looks like: accusing people who actually are matching their beliefs to the evidence of ignoring or suppressing evidence, while ignoring or suppressing evidence yourself, and maintaining a belief irrationally disproportionate to—indeed in direct contradiction with—the actual evidence (see my old talk “Are Christians Delusional?”, although also keep in mind my caveats about using a mental illness model of religion).

Delusions Even of What’s in Scripture

McIntyre affords us an example almost immediately in another article, where in “Truth Whack-a-Mole” he declares, with bizarre earnestness, that “Contrary to what some think, doubts and questions are not condemned in Scripture.”

Um. Dude. Yes they are. And they’re never praised or encouraged either.

In the Epistle of James we’re told:

If any of you lacks wisdom, you should ask God, who gives generously to all without finding fault, and it will be given to you. But when you ask, you must believe and not doubt, because the one who doubts is like a wave of the sea, blown and tossed by the wind. That person should not expect to receive anything from the Lord. Such a person is double-minded and unstable in all they do. JAMES 1:5-8

In First Timothy (1 Timothy 1:6-7 and 6:3-4) and Second Timothy we’re told not to “wrestle with” the definitions or meanings of words because that kind of questioning is “useless” and leads “to the ruin of the hearers,” in fact any questioning and debate are worldly and vacuous and only lead to “godlessness,” and even talking about one’s doubts and questions will only spread evil like a disease (2 Timothy 2:14-17). Thus “have nothing to do with stupid and senseless controversies,” we’re told, because they only “breed quarrels” (2 Timothy 2:23).

And how do you tell what is a “stupid and senseless controversy”? The gist you get everywhere in scripture is that it’s anything contrary to what you were first taught (e.g. Galatians 1:6-9). You don’t need to investigate anything beyond that because “the Lord will give you understanding in everything” (2 Timothy 2:7). In other words, don’t doubt or deviate from what you were first told. Don’t analyze or argue. Don’t discuss your doubts and differing conclusions with anyone. Doing so is wicked. Even having doubts makes you unstable, and unworthy of any support from God.

Everywhere else the subject comes up, this same sentiment is reinforced. Reject philosophical analysis as wicked (Colossians 2:8; Ephesians 4:13-15). The questioners of the world are damnable fools (1 Corinthians 1:20). Every thought and question must be subdued and made captive to Christian doctrine (2 Corinthians 10:4-5). In Luke 1:18-22 Zechariah is struck mute for merely asking for evidence. In John 20:29 we’re only told those who believe without evidence are blessed—thus belittling Thomas for merely asking for evidence, the real message of that passage. Hebrews 11 establishes we should just trust the things we’re told, and not expect there to be evidence (and yes, that’s what it says: see Not the Impossible Faith, pp. 236-40).

Doubts and questions are uniformly discouraged in scripture. Indeed I demonstrate this was a general feature of Christianity and Christian scripture for centuries in Chapter 5 of The Scientist in the Early Roman Empire (see also Chs. 7, 13, and 17 of my book Not the Impossible Faith). There is no example in scripture where it’s said that doubt and questioning are cool; to the contrary, plenty of passages communicate the opposite. So how has McIntyre deluded himself into thinking his Scriptures say otherwise? By literally ignoring all the evidence.

Has Liberty Not Made Anyone Happy?

Another such example of McIntyre’s delusionality shows in another article (his most recent as of this writing), “Bars of Wood to Bars of Iron”, where he complains that all our increased freedoms and social progress haven’t made the world better, seriously asking:

But are we any happier as a society? Have the new-found freedoms brought personal peace? Based on the angry rhetoric from those who most loudly proclaim freedom from limits, I struggle to see that we are indeed happier. Perhaps we have exchanged what has been perceived as a yoke and exchanged it for a collar of iron.

Of course one might not marvel at how an able straight white man wouldn’t “see” how things have gotten better—never part of a group having been shit on for centuries as a woman or a black or gay man or a disabled person, and so on. “We ended slavery and enfranchised women and stopped imprisoning gay people and passed the Americans with Disabilities Act, but we’d be better off going back and having slaves again and only men voting and queers off the street and cripples even further disadvantaged” is of course the sort of thing only someone completely blind to the improvements these things have entailed to the happiness and welfare of black people and women and gay men and the disabled would ever say.

Ignoring vast realms of evidence—even because of such intense bigotry as to blind oneself to entire realms of reality—is indeed another data point evincing how deluded this guy is. But even outside his racism and sexism and homophobia and ableism and every other bigoted bias blinding him, his statement still ignores other vast realms of evidence to the contrary. As Stephen Pinker and Michael Shermer have documented, the data show considerable improvements worldwide on every measure of pursuing human happiness, from reductions in poverty and violence and morbidity and mortality to measured increases in societal contentment. People are only angry we haven’t gotten farther precisely because there is now no justification for continuing to tolerate so much, given how much we’ve proved we can eliminate. People are angry at so many stalwart attempts like McIntyre’s to go backwards, and thus lose all we’ve gained.

And indeed, the data show one other very secure fact: we now know, both chronologically and geographically (from studies as diverse as those of Gregory Paul to Phil Zuckerman), that the more we remove religion and replace it with meaningful democracy and secular human rights (and yes, they’re secular), the better all these measures improve across an entire population. But alas, McIntyre “sees no improvement” in the world. When you are that certain of a conclusion in the face of such vast evidence to the contrary, you are delusional. You might want to see to that. You need to figure out what’s causing this severe impairment in your empirical access to reality. And in case you can’t figure out what is disabling you, I have a hint: it’s your religion.

Missing All the Evidence

But back to the article I started with. McIntyre goes on there to declare:

I have come to realize that those who refuse to believe (it is a will issue, first and foremost) have to spend a lot of energy whacking down those truth moles as they pop up. How are you going to respond to the claims Jesus made about himself? How could the complexity we see in biology happen by chance? Can you really live as though there are no absolute truths? Why is it that so many believe in the supernatural? These are examples of questions, like moles, that pop up and must be swept aside to remain antagonistic to belief. Those who are truly wrestling with these questions are more open to dialog.

These are not moles. They’re corpses. The reason we don’t “keep entertaining” them is that they’ve been decisively answered already, crushed under tons of plain evidence. “How are you going to respond to the claims Jesus made about himself?” Confront the entirety of mainstream Biblical scholarship today (like, you know, this, this, this, this, …). “How could the complexity we see in biology happen by chance?” Confront the entirety of evolution science including contemporary protobiology. “Why is it that so many believe in the supernatural?” Confront the entirety of the cognitive science of false beliefs (like, you know, this, this, this, this, …).

The evidence is all there. McIntyre ignores it. Why? Because he hasn’t learned how vulnerable to false beliefs humans are, and thus he himself is. “Can you really live as though there are no absolute truths?” Yeah. Every significant belief has a nonzero probability of being false. That’s a fact. And humans can and must learn to cope with that fact if they are to comprehend and navigate reality competently and honestly—while those who don’t learn to cope with this fact become delusional. McIntyre wants a certainty that doesn’t exist. And his resulting quest for it leads him to a delusional superstition, where he remains trapped by stupid questions like “Can you really live as though there are no absolute truths?”

Of course we well know we can’t trust that anything we’re told Jesus said, he actually said. Nor that even if he said it, he didn’t as mistakenly believe it as any of hundreds of other self-declared saviors did. McIntyre would admit this of any other religion but his. That’s why he’s delusional.

Of course we well know evolution by natural selection has explained or can explain every single complexity in any organism on earth, and that the first life arising by chance accident is not only highly probable in such a large and old cosmos but exactly matches all observations.

Of course we well know we can only be certain of anything to varying degrees of probability, and that “absolute certainty” is a characteristic of delusion, not wisdom. This is as true of physical facts of the world as of morality or any other domain of knowledge. Admitting this is a requirement of a competent mind.

Of course we well know people believe, and have believed, tons of obviously false supernatural nonsense, and done so because our brains were not intelligently designed and make countless errors in evaluating reality, unless we tame our errant brains with more reliable methods. In fact this is actually evidence against the existence of any concerned god.

Every attempt to avoid these conclusions with rationalizations that always fall apart when analyzed only further demonstrates how delusional Christians resorting to such defenses are.

Conclusion

All theism is built on ignoring evidence. Atheists as a whole have already met their burden of evidence in showing the existence of any imagined god is extraordinarily improbable. The burden is therefore now on theists to find and present some convincing evidence to the contrary—without hiding all the evidence that changes that conclusion! They’ve failed. They’ve failed for thousands of years. So the odds of ever succeeding now are so low as to guarantee anyone still trying can only be delusional.

The ignorant may have an excuse, but not for long. Because it’s not plausibly possible to be a person out in the world today and not find out about all this vast evidence against any plausibility of a god. So one can only persist in believing there is one by choosing to ignore that. And choosing to ignore evidence that would change your mind precisely to avoid changing your mind—whether ignoring that evidence altogether or ignoring its rational consequence to any conclusion—is precisely what it means to be delusional. And that indicates you have a commitment to your beliefs for reasons other than evidence. You might want to seriously confront what those reasons are.

And then understand that wanting a thing to be true, does not make it so.

November 10, 2019

Another Way To Help

Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?, Paul Gauguin

Another way to help the website is by sharing posts you like to:

Facebook; Reddit; Twitter; Tumblr; Pocket; Pinterest; WhatsApp

Sharing to Reddit’s philosophy sub-reddit is a particularly good way to drive traffic to the site but unfortunately they don’t allow me to share links to my own site. And you can link any post, including old ones. Thanks to all my readers in advance if you can help.

All the best, John

November 8, 2019

So Much To Learn; So Little Time

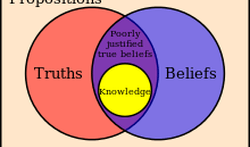

Euler diagram representing a definition of knowledge

Euler diagram representing a definition of knowledge

The last two posts on the blog “Socrates: I know that I know nothing,” and “The Limits of Knowledge,” have been about epistemology—the study of the nature and limits of human knowledge.

Regarding the former post, I have always intrepreted the Socratic limitation on knowledge as Socrates’ recognition that there was so much he didn’t know. And he was wiser than others in precisely this way—he was aware of his own ignorance. That’s how, corectly or not, I taught the issue to generations of students.

The latter post is a reflection on intellectual humility, something the world desperately needs. Those who believe they possess a monopoly on truth cause so much trouble in the world.

Bertrand Russell poignantly captures how philosophy aids our humility while undermining our intellectual certainty,

Philosophy … while diminishing our feeling of certainty as to what things are … greatly increases our knowledge as to what they may be; it removes the somewhat arrogant dogmatism of those who have never travelled into the region of liberating doubt …

So good thinking entails the realization of our fallibility—any idea we have might be mistaken. Limitations on knowledge are further supported by Godel’s Incompleteness theorems in mathematics and the Heisenberg uncertainty principle in quantum mechanics.

But note. It’s the ignorant who are most sure of themselves:

“Ignorance more frequently begets confidence than does knowledge.”

~ Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man, 1871.

“The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.” ~ W. B. Yeats, “The Second Coming,” 1920.

“The fundamental cause of the trouble is that in the modern world the stupid are cocksure while the intelligent are full of doubt.” ~ Bertrand Russell, “The Triumph of Stupidity,” 1933.

It seems all three men anticipated the Dunning-Kruger hypothesis.

Reflecting on knowledge, one of his great passions, Russell said “a little of this but not much I have achieved.” Consider that for a moment. Perhaps the greatest philosopher of the 20th century, perhaps the greatest logician of the 20th century, one of the greatest mathematicians of the 20th century, and a Nobel laurate in literature expressing such intellectual humility. Contrast his attitude with the certainty of so many ignorant people.

All of this reminds me of some lines from Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure,

But man, proud man,

Drest in a little brief authority,

Most ignorant of what he’s most assur’d;

His glassy essence, like an angry ape,

Plays such fantastic tricks before high heaven,

As make the angels weep.

My own limitations on what I know and can know confront me daily as my time runs out. There is so much I want to learn, but so little time. Here’s are simple examples. I receive daily notifications on academia of articles I want to read but I simply don’t have time. I also get daily emails from people suggesting books and articles that I’m interested in, but I don’t have time to read them either. I scan the New York Times, Washington Post, Vox, Salon, Slate, Aeon, and many other sites but I simply can’t read it all.

Oh to be like Mr. Data on Star Trek and just immediately download it all into my brain. (Another reason for intelligence augmentation, a global brain, artificial intelligence, neural implants, etc.) For now I’ll just have to slog along with the brain I have. But if I can’t have a better brain, I wish I could have more quality time so that I could learn more. That would be worth more to me than the world’s riches.

This is not to say that all claims are relative. For example I am extraordinarily confident about the basic theories of modern science—quantum, atomic, gravitational, evolutionary, heleocentric, etc. as these are our most certain pieces of knowledge, supported by overwhelming amounts of evidence. Regarding all claims I proportion my assent to the evidence.

Still I admit, to quote Shakespeare again, that (probably)

There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio,

Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.

– Hamlet (1.5.167-8), Hamlet to Horatio

_________________________________________________________________

** Knowledge as justified true belief is controversial because of the Gettier problem.

November 6, 2019

The Limits of Knowledge

Chris Crawford at Cologne Game Lab in 2011

Chris Crawford at Cologne Game Lab in 2011

© Chris Crawford– (Reprinted with Permission)

https://www.erasmatazz.com/personal/s...

You don’t know jack. Neither do I. The world is far more complex than we realize. I have spent a lifetime learning about a huge range of topics: physics, mathematics, biology, linguistics, politics, economics, geology, evolution, computers, electronics, history, law, astronomy, psychology — it’s a long list. The more I have learned, the more insights I gain into the operation of reality, the more connections I see between all the different fields, and the more unified the universe seems to me.

Yet the expansion of my knowledge has only served to reveal just how miniscule my knowledge is. That is the inevitable consequence of the nature of knowledge. Your knowledge of reality falls into three classes:

1. What you know.

2. What you can see that you don’t know.

3. What you cannot see; you don’t even know that you can’t see it.

The knowledge you already possess provides you with your viewpoint of reality. From the perch of your knowledge, you can scan the horizon, taking in all the terrain that you don’t know yet. You can set out to explore that territory and expand your knowledge. But you cannot see beyond your horizon. You have no idea what — if anything — lies beyond the limits of your vision. You don’t know just how ignorant you are. Most people are so intellectually provincial that they think that their knowledge of reality is adequate to inform all their decisions.

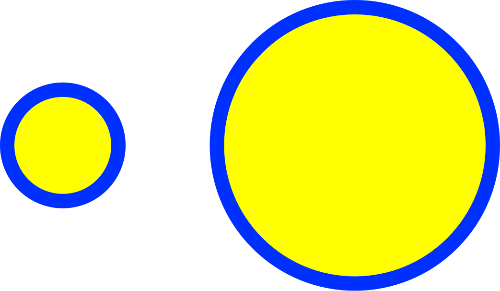

Here are pictorial representations of the perception of reality of two different people. On the left is a more ignorant person. What he knows is yellow. The only things that he thinks he doesn’t know are the things that can be conceived in light of his limited understanding. They are represented by the blue boundary. Meanwhile, the vast terrain of truth outside his vision is simply lost upon him.

On the right is a less ignorant person. He knows more, so his appreciation of what he doesn’t know is greater than that of the more ignorant person. As he has accumulated more knowledge, his circle of appreciation has expanded and now he realizes that there is even more that he doesn’t know. Even then, however, his vision is still limited by the confines of his existing knowledge.

It gets worse: we don’t even know the scale of this representation. Let’s see those two circles in the context of the entirety of reality, which I will color pink. How do we know which of these two representations is more accurate?

I think that we can all agree that the representation on the right is closer to the truth. But how much further must we shrink the yellow circles to reach a proper representation?

A case in point: the orbit of the moon

To illustrate just how complicated reality can be, let’s take a simple case: the orbit of the moon. We all know that the moon orbits the earth, right? So we can write down a simple formula for the moon’s orbit:

The moon’s orbit has a radius of 385,000 km and a period of 27.322 days.

That was easy, wasn’t it? Oh, wait, the moon doesn’t orbit in a perfect circle. Its orbit is an ellipse. So we must add a correction; it’s called the eccentricity of the moon’s orbit, and it is 0.05488.

Oh, wait, there’s another problem: the moon’s orbit isn’t in the same plane as the earth’s equator. It’s orbit is inclined relative to the earth’s equator. That orbital inclination is 5.15º.

OK, now we have it down pat, right? Wrong, of course! The moon’s orbit is also tilted relative to the earth’s orbital plane, by about 1.5º.

I’m just getting warmed up. The moon is also affected by solar gravitation; half the time it is closer to the sun than the earth, and half the time it is further away. The difference amounts to about 0.5% of the net gravitational pull of the sun on the earth, so it definitely shifts the moon.

The other planets also affect the moon, but their effects are tiny. Even so, we can see those effects in the motion of the moon.

We’re not done yet. The moon is lopsided. It’s not a perfectly symmetrical sphere; the side facing us is slightly more massive than the back side. That causes the same side of the moon to always face the earth.

Oops, it’s not quite that simple — in fact, the moon nods slightly back and forth as it orbits the moon. Oh, and its axis of rotation is not quite perpendicular to the plane of its orbit, so it appears to yaw up and down a little.

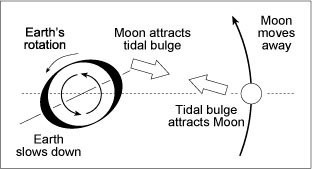

I’ve left out the juiciest bit for last: the tides. The moon attracts the ocean water, which causes the tides, which are typically only a meter or two high. But the ocean water encounters some friction as it moves, which retards the tides. The highest tide always occurs some hours AFTER the moon is highest in the sky. That friction in turn causes the earth’s rotation to slow. Even more interesting, though, is that it pushes the moon away from the earth:

Another thing: the magnitude of the tidal effect depends on what part of the earth is facing the moon. There isn’t much tidal effect when the moon is over Europe and Africa, because those longitudes are mostly land. On the other hand, the tidal effect is really strong when the moon is over the Pacific, because there’s very little land.

There’s another tidal effect from the fact that the earth’s core is molten; it responds to the changes in lunar gravity in ways that ALSO effect the moon’s orbit.

While I was in grad school, one of my professors referred to an equation for the orbit of the moon that took into account all of these factors. It had something like 120 terms. I have been unable to find that equation on the Internet.

The moral of this story should be clear: even something so apparently simple and straightforward as the orbital motion of the moon turns out to be immensely complicated. Keep that in mind as you deal with more complicated questions.

Brief Reflections

The above is a sublime reflection on intellectual humility, something the world desperately needs. So much trouble in the world is caused by those who believe they possess a monopoly on truth. As Bertrand Russell so poignantly put it:

Philosophy … while diminishing our feeling of certainty as to what things are … greatly increases our knowledge as to what they may be; it removes the somewhat arrogant dogmatism of those who have never travelled into the region of liberating doubt …

But a caveat. It’s the ignorant who are most sure of themselves:

“Ignorance more frequently begets confidence than does knowledge.”

~ Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man, 1871.

“The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.” ~ W. B. Yeats, “The Second Coming,” 1920.

“The fundamental cause of the trouble is that in the modern world the stupid are cocksure while the intelligent are full of doubt.” ~ Bertrand Russell, “The Triumph of Stupidity,” 1933.

It seems all three men anticipated the Dunning-Kruger hypothesis.

November 3, 2019

Socrates: “I know that I know nothing”

The Delphic Tholos

The Delphic Tholos

© Paul Bonea (Reprinted with Permission)

https://hastyreader.com/the-only-thin...

I know that I know nothing – 5 interpretations

A good friend of Socrates, once asked the Oracle at Delphi “is anyone wiser than Socrates?”

The Oracle answered “No one.”

This greatly puzzled Socrates, since he claimed to possess no secret information or wise insight. As far as Socrates was concerned, he was the most ignorant man in the land.

Socrates was determined to prove the Oracle wrong. He toured Athens up and down, talking to its wisest and most capable people, trying to find someone wiser than he was.

What he found was that poets didn’t know why their words moved people, craftsmen only knew how to master their trade and not much else, and politicians thought they were wise but didn’t have the knowledge to back it up.

What Socrates discovered was that none of these people knew anything, but they all thought they did. Socrates concluded he was wiser than them, because he at least knew that he knew nothing.

This at least is the story of the phrase. It’s been almost 2500 years since its longer form was initially written. In that time, it has caught a life of its own and now has many different interpretations. [Here are five of them.]

1) I know that I know nothing, because I can’t trust my brain

One interpretations of the phrase asks if you can be 100% certain if a piece of information is true.

Imagine this question: “Is the Sun real?”

If it’s day time, the answer is immediately obvious because you can simply point your hand at the Sun and say: “Yes, of course the Sun is real. There it is.”

But then, you will fall into something called the infinite regress problem. This means every proof you have, must be backed up by another proof, and that proof too must be backed up by another one. As you go down the infinite regress, you will reach a point where you have no proof to back up a statement. Because that one argument can’t be proven, it then crashes all of the other statements made up to it.

As you go down the infinite regress, you will reach a point where you have no proof to back up a statement. Because that one argument can’t be proven, it then crashes all of the other statements made up to it.

French philosopher Rene Descartes went so far with the infinite regression, that he imagined the whole world was just an elaborate illusion created by an Evil Demon that wanted to trick him.

As the Evil Demon scenario shows, the infinite regression will often go so far down it will challenge whether any of the information entering your brain is real or not.

Thus, if all the information you’re receiving through the senses is an illusion, then by extension you know nothing.

Counterarguments: Descartes came up with the phrase “I think, therefore I am”. This puts a stop to the infinite regress since it’s impossible to doubt your own existence because simply by thinking, you prove that your consciousness exists.

Another philosophical counter argument is that some statements do not require proof in order to be called true. These are called self-evident truths, and include statements such as:

2+2 = 4

A room that contains a bed is automatically bigger than the bed.

A square contains 4 sides.

These self-evident truths act as foundations stones that allow knowledge to be built upon.

2) I know that I know nothing, because the physical world isn’t real

Socrates never left behind any written texts (mostly because he hated writing, saying it would damage our memory). All of the things we know about Socrates comes mostly from Plato, and to a lesser extent, Xenophon.

However, Plato wrote his philosophy in dialogue form and always used Socrates as the voice for his own ideas. Because of this, it’s almost impossible to separate the true Socrates from Plato.

One interesting interpretation of “I know that I know nothing”, is that the phrase could actually belong to Plato, alluding to one of his ideas: the theory of forms.

According to theory of forms, the physical world we live in, the one where you can read this article on a monitor or hold a glass of water, is actually just a shadow.

The real world is that of “ideas” or “forms”. These are non-physical essences that exist outside of our physical world. Everything in our dimension is just an imitation, or projection of these forms and ideas.

Another way to think about the forms, is to compare something that exists in the real world vs. its ideal version. For instance, imagine the perfect apple, and then compare it to real world apples you’ve seen or eaten.

The perfect apple (in terms of weight, crunchiness, taste, color, texture, smell etc.) only exists in the realm of forms, and every apple you’ve seen in real life is just a shadow, an imitation of the perfect one.

That being said, the theory of forms does have some major limitations. One of them is that a human living in the physical / shadow realm, you can never know how an ideal form looks like. The best you can do is to just think what a perfect apple, human, character, marriage etc. look like, and try to stick to that ideal as much as possible.

You’ll never know for sure what the ideal looks like. In this sense, “I know I know nothing” can mean “I only know the physical realm, but I know nothing about the real of forms”.

3) I know that I know nothing, because information can be uncertain

A more straightforward interpretation is that you can never be sure if a piece of information is correct. Viewed from this perspective, “I know that I know nothing” becomes a motto that stops you from making hasty judgement based on incomplete or potentially false information.

This interpretation is also connected with the historical context in which Socrates (or Plato) uttered the phrase. At the time, Pyrrhonism was a philosophical school that claimed you cannot discover the truth for anything (except the self-evident such as 2+2=4).

From the Pyrrhonist point of view, you cannot say for sure if a statement is correct or false because there will always be arguments for and against that will cancel each other out.

For instance, imagine the color green.

A Pyrrhonist would argue that you cannot be sure this is the color green because:

Animals might perceive this color differently.

Other people might perceive the color differently because of different lighting, color blindness etc.

A non-philosopher would just say “it’s green dammit, what more do you need?” and close the problem.

What makes Pyrrhonists different is that instead of saying “yes this is a color, and that color is green”, they will simply say “yes, this is a color, but I’m not sure which so I’d rather not say.”

For Pyrrhonists however, such a position was not just a philosophical exercise. They extended this way of thinking to their entire lives so it became a mindset called epoché, translated as suspension of judgement. This suspension of judgement then led to the mental state of ataraxia, often translated as tranquility.

From the Pyrrhonist point of view, people cannot achieve happiness because their minds are in a state of conflict by having to come to conclusions in the face of contradictory arguments.

As a result, Pyrrhonists chose to suspend their judgement on all problems that were not self-evident, hoping that thus they will achieve true happiness.

Ultimately, from the Pyrrhonist perspective, “I know that I know nothing” can mean “truth cannot be discovered”.

4) I know that I know nothing – the paradox

A more conventional approach to the phrase is to simply view it as a self-referential paradox. The most well-known self-referential paradox is the phrase “this sentence is a lie”.

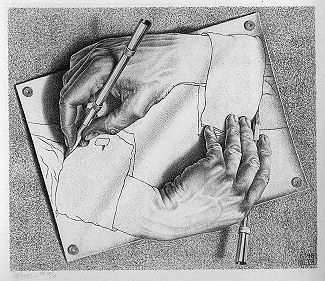

Pair of drawing hands by M.C. Escher

When it comes to science and knowledge, paradoxes function as indications that a logical argument is flawed, or that our way of thinking will produce bad results.

A more interesting overview of self-referencing paradoxes is the book Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid by Douglas Hofstader. This book explores how meaningless elements, (such as carbon, hydrogen etc.) form systems, and how these systems can then become self-aware through a process of self-reference.

5) I know that I know nothing – a motto of humility

Socrates lived in a world that had accumulated very little knowledge.

As a fun fact, Aristotle (who was born some 15 years after Socrates died), was said to be the last man on Earth to have known every ounce of knowledge available at the time.

From the perspective of Socrates, any knowledge or information he did have was likely to be insignificant (or even completely false) compared to how much was left to be discovered.

From such a position, it’s easier to say “I know that I know nothing” rather than the more technical truth: “I only know the tiniest bit of knowledge, and even that is probably incorrect”.

The same principle still applies to us, if we compare ourselves to humans living 200-300 years in the future. And unlike Socrates, we have a giant wealth of information to dive in whenever we want.

[For more see: Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I know_that_I_know_nothing ]

Etymology[edit]

The phrase, originally from Latin (“ipse se nihil scire id unum sciat“[2]), is a possible paraphrase from a Greek text (see below). It is also quoted as “scio me nihil scire” or “scio me nescire“.[3] It was later back-translated to Katharevousa Greek as “[ἓν οἶδα ὅτι] οὐδὲν οἶδα“, [èn oîda óti] oudèn oîda).[4]

In Plato[edit]

This is technically a shorter paraphrasing of Socrates’ statement, “I neither know nor think that I know” (in Plato, Apology 21d). The paraphased saying, though widely attributed to Plato’s Socrates in both ancient and modern times, actually occurs nowhere in Plato’s works in precisely the form “I know that I know nothing.”[5] Two prominent Plato scholars have recently argued that the claim should not be attributed to Plato’s Socrates.[6]

Evidence that Socrates does not actually claim to know nothing can be found at Apology 29b-c, where he claims twice to know something. See also Apology 29d, where Socrates indicates that he is so confident in his claim to knowledge at 29b-c that he is willing to die for it.

That said, in the Apology, Plato relates that Socrates accounts for his seeming wiser than any other person because he does not imagine that he knows what he does not know.[7]

… ἔοικα γοῦν τούτου γε σμικρῷ τινι αὐτῷ τούτῳ σοφώτερος εἶναι, ὅτι ἃ μὴ οἶδα οὐδὲ οἴομαι εἰδέναι.

… I seem, then, in just this little thing to be wiser than this man at any rate, that what I do not know I do not think I know either. [from the Henry Cary literal translation of 1897]

A more commonly used translation puts it, “although I do not suppose that either of us knows anything really beautiful and good, I am better off than he is – for he knows nothing, and thinks that he knows. I neither know nor think that I know” [from the Benjamin Jowett translation].

Whichever translation we use, the context in which this passage occurs should be considered; Socrates having gone to a “wise” man, and having discussed with him, withdraws and thinks the above to himself. Socrates, since he denied any kind of knowledge, then tried to find someone wiser than himself among politicians, poets, and craftsmen. It appeared that politicians claimed wisdom without knowledge; poets could touch people with their words, but did not know their meaning; and craftsmen could claim knowledge only in specific and narrow fields. The interpretation of the Oracle’s answer might be Socrates’ awareness of his own ignorance.[8]

Socrates also deals with this phrase in Plato’s dialogue Meno when he says:[9]

καὶ νῦν περὶ ἀρετῆς ὃ ἔστιν ἐγὼ μὲν οὐκ οἶδα, σὺ μέντοι ἴσως πρότερον μὲν ᾔδησθα πρὶν ἐμοῦ ἅψασθαι, νῦν μέντοι ὅμοιος εἶ οὐκ εἰδότι.

[So now I do not know what virtue is; perhaps you knew before you contacted me, but now you are certainly like one who does not know.] (trans. G. M. A. Grube)

Here, Socrates aims at the change of Meno’s opinion, who was a firm believer in his own opinion and whose claim to knowledge Socrates had disproved.

It is essentially the question that begins “post-Socratic” Western philosophy. Socrates begins all wisdom with wondering, thus one must begin with admitting one’s ignorance. After all, Socrates’ dialectic method of teaching was based on that he as a teacher knew nothing, so he would derive knowledge from his students by dialogue.

There is also a passage by Diogenes Laërtius in his work Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers where he lists, among the things that Socrates used to say:[10] “εἰδέναι μὲν μηδὲν πλὴν αὐτὸ τοῦτο εἰδέναι“, or “that he knew nothing except that he knew that very fact (i.e. that he knew nothing)”.

Again, closer to the quote, there is a passage in Plato’s Apology, where Socrates says that after discussing with someone he started thinking that:[7]

τούτου μὲν τοῦ ἀνθρώπου ἐγὼ σοφώτερός εἰμι· κινδυνεύει μὲν γὰρ ἡμῶν οὐδέτερος οὐδὲν καλὸν κἀγαθὸν εἰδέναι, ἀλλ᾽ οὗτος μὲν οἴεταί τι εἰδέναι οὐκ εἰδώς, ἐγὼ δέ, ὥσπερ οὖν οὐκ οἶδα, οὐδὲ οἴομαι· ἔοικα γοῦν τούτου γε σμικρῷ τινι αὐτῷ τούτῳ σοφώτερος εἶναι, ὅτι ἃ μὴ οἶδα οὐδὲ οἴομαι εἰδέναι.

I am wiser than this man, for neither of us appears to know anything great and good; but he fancies he knows something, although he knows nothing; whereas I, as I do not know anything, so I do not fancy I do. In this trifling particular, then, I appear to be wiser than he, because I do not fancy I know what I do not know.

It is also a curiosity that there is more than one passage in the narratives in which Socrates claims to have knowledge on some topic, for instance on love:[11]

How could I vote ‘No,’ when the only thing I say I understand is the art of love (τὰ ἐρωτικά)[12]

I know virtually nothing, except a certain small subject – love (τῶν ἐρωτικῶν), although on this subject, I’m thought to be amazing (δεινός), better than anyone else, past or present[13]

October 31, 2019

Does Science Destroy Mystery? Reply to Van de Cruys

Clerks studying astronomy and geometry (France, early 15th century).

In the previous post, Dr. Sander Van de Cruys argued,

I want to take seriously the feeling or complaint of people in the arts that science disenchants the world, or more broadly takes ‘something’ away from it … It seems totally possible to be enchanted by the ‘quest’, the hunt for making things comprehensible or predictable, while at the same time be thoroughly displeased or even depressed by the resulting worldview.

The first thing I’d say in reply is that, since any scientific conception of the world is provisional, what science eventually reveals may not be as depressing as Sander imagines. Also, I prefer truth to illusion even if the truth isn’t as comforting. Furthermore, I don’t think it’s clear that most religious metaphysics are especially comforting given how they demand that humans must appease the Gods, worry about everlasting torment, etc.

Turning to some of Sander’s specific claims in support of his thesis, he argues that “the intrinsic value that we as humans can attach to a human or organism in itself, irrespective of merits or capacities, is something quite alien from a scientific point of view.” But I doubt this is true. We can attach intrinsic value to our spouse, for example, despite the fact that something about our psychology or our ability to pair bond or pheromones largely explain this. At one level I know that my wife and I are biological machines, but this doesn’t detract from us loving each other at another level.

Sander also claims: “If science produced the same kind of deep wonder and inspiration as prescientific worldviews, we would now have a lot of great artworks inspired by science instead of religion.” One issue here is that most people are scientifically illiterate; they simply don’t know enough about science to be inspired by it. Another issue is that modern science is only a few hundred years old so religion has had a much longer time to be associated with art. Moreover, I doubt many would prefer a world with more art and less science.

Furthermore, if religion inspires more art than science this may be because art is one of the few ways religion can express its mysteries. Scientists may feel awe when looking at the universe, but they don’t have to draw paint pictures or sing to express those feelings. Instead, they advance hypotheses and conduct experiments to express themselves. Note that this disparity in the means of expression is unrelated with the consolation provided by religious mystery vs. science. When you get an antibiotic instead of dying from an infection you will find science plenty comforting.

Sander’s argument may also have a lot to do with our definition of art. Consider a portrait or landscape painting, mainstays of art before the scientific revolution. While previously ubiquitous, these have been replaced by photographs, motion pictures, and motion pictures with sound. In fact, these new technologies do inspire art. In fact, the whole genre of science fiction wouldn’t be possible without inspiration from science.

Sander also claims that we might eventually “have the technology (based on solid science) to detect, based on micro-expressions or other physiological data, the true motivations of what someone says. A kind of lie detection on steroids. Would it improve our daily interactions? … to the contrary.”

Maybe its the transhumanist in me or having Trump as the US president, but I think we would benefit tremendously from having such a lie detector test. Truth telling is as close to a universal moral prescription as there is and it is necessary for mutually beneficial human interaction.

Sander also considers the idea that our self-image in more accurate when we’re depressed and he concludes that delusions are thus functional. I suppose delusional thinking may sometimes be beneficial, but its costs outweigh its gains in my view. (Think of how much trouble psychopaths and narcissists cause.) Moreover, I don’t know if the depressed do better when they have an illusory view of themselves so much as when they have a realistic view of the world. And even if something is lost when science replaces religion, something much greater has been gained. Knowledge has replaced ignorance and superstition.

Sander concludes: “I suspect science cannot make up for much of the emotional lacuna … it created itself by displacing religious worldviews. I think this might boil down to a need for consolation for the human condition that science does not … have an answer to …”

While I sympathize with the idea that something is lost if mystery disappears from the world, I’d argue that the universe that science has revealed is vastly more mysterious and interesting than any story deriving from creation myths and heavenly afterlife. As for the mysteries eliminated, I’m glad we know that matter is composed of atoms, that the universe is billions of years old, and that evolution made the species. Without such knowledge we were in the dark, and the light is so much better.

However, I understand that some will always prefer their creation myths and other fairy tales—myth does have power as Joseph Campbell taught us. (The real issue here may be one of science not revealing meaning when compared to pre-scientific views. Yet it’s not clear how gods give life meaning as many philosophers have pointed out.)

Finally, I think Sander may be idealizing the emotional comfort religion provides. Consider the vast number of unhappy believers and the untold amount of suffering that religion has caused, and continues to cause. And even if there is some short-term payoff for ingesting religious drugs it is easy to see the horrors such consolation entails.

In the end, human beings must grow up and face the world as it is. They do this in large part by understanding and accepting the world revealed by modern science. After all science is the only cognitive authority in the world today and the greatest achievement of human civilization.

Growing up and putting aside ignorance and superstition is the necessary precondition of both our survival and flourishing. We either will evolve or we will perish.

October 28, 2019

Does Science Destroy Mystery?

Wrisberg epitaph in Hildesheim Cathedral, showing the distribution of the divine graces by means of the church and the sacraments, or mysteries. By Johannes Hopffe 1585.

© Sander Van de Cruys, Ph.D.– (Reprinted with Permission)

http://www.sandervandecruys.be/

(Some of my colleagues have been discussing the appeal of mystery—especially why people resent that science tries to solve mysteries, often preferring pseudo-scientific, religious, or other supernatural explanations. One explanation offered is that knowledge excludes miraculous cures while mystery does not. In such cases it is easy to see why believing in mystery would be appealing. In reply, Dr. Sander Van de Cruys penned the following.)

Thanks for sharing this insight in the appeal of mystery. It intuitively rings true for me. However, I want to take seriously the feeling or complaint of people in the arts that science disenchants the world, or more broadly takes ‘something’ away from it. Indeed, I think this feeling is broadly shared, not only by people in the arts but also by people who are on the scientist’s end of the spectrum (e.g. myself). It seems totally possible to be enchanted by the ‘quest’, the hunt for making things comprehensible or predictable, while at the same time be thoroughly displeased or even depressed by the resulting worldview.

Indeed, discovering the deeper regularities that allow us to thriftily “compress” phenomena, as we sometimes succeed to do in science, can be a brief silver lining for the world science discloses. Insights that are very bleak, but increase our predictive grasp, can be deviously pleasurable. I count the theory of evolution by natural selection among this type of insight. It gives me a deep grasp of the regularities that govern a multitude of living creatures (and their niches).

But at the same time, these forces are mechanistic, passive (selective dying instead of ‘selecting’) and indifferent to the concerns of the agents, except insofar as it pertains to fitness. For example, even “kind behaviors” emerges as strategies to optimize fitness in a particular niche (see Frans de Waal’s work). The criterion is this mindless competition, which gives the insight its sense of elegance (in the scientist) but at the same time the sense of alienation (in many others).

As humans, we can value kindness as an end in itself, but we’re fighting against the tide here, against social and evolutionary forces that just succeed because they produce succession. Succession (fitness) is orthogonal to kindness. One could of course point to the deep connection between organisms, as shown by evolutionary biology. That can be a consolation, an uplifting story about our shared fight against demise/entropy. However, it easily dissolves because we regularly (have to) fight against each other (within and between species). Symbiosis can easily veer into parasitism. Indeed, much of what ‘succeeded’ in history (the landmarks of civilization) were products of a form of parasitism. “There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.”

So the intrinsic value that we as humans can attach to a human or organism in itself, irrespective of merits or capacities, is something quite alien from a scientific point of view. Hence the alienation in people’s experience with science. Even pleas for diversity (in capacities of) human beings or in biosystems are often motivated by appealing to the greater creativity or resilience of a (social) system (good for the further continuation/adaptation of the system). Such utilitarian reasons should, I think, not be what deplete ethical ‘personhood’.

So I don’t think we can wash away people’s discontent with secularized, scientific/technological civilization by saying: Yes, but science still has a lot of uncertainty and wonder. If science produced the same kind of deep wonder and inspiration as prescientific worldviews, we would now have a lot of great artworks inspired by science instead of religion. Instead, when art is inspired by science, I mostly see interesting gimmicks instead of expressive art (I may show my limited knowledge of modern art here).

In terms of experience (of smelling a flower, of feeling love, etc), I think a scientific analysis does rob us of something, diminishing or shortening the ‘mystery’ or full, intense experience. The very act of analyzing already does this, if not the product of the analysis. This is despite the initial wonder that instigates the analysis, or the admiration and pleasure that might be secondarily created by a scientific explanation. One could compare the latter to admiration or wonder about a musician’s technical craftsmanship or virtuosity. It’s real and pleasurable, but it does not concern the emotional expressiveness of his/her music. It’s a different kind of wonder. So I don’t agree with Dawkins and the like who say that science only increases the experience (of wonder).

Probably the reflex to (scientifically) analyze/explain is born out of the uncertainty attached to the mystery, and our inability to just stay with the ambivalence. Of course, this would hold for religious explanations as well. However, in a prescientific, religious worldview, explanations are structured by an appeal to agents with rich goals, concerns, and motivations all around you, benevolent or bad, but not indifferent. For humans, this seems to be a world where they can feel more at home.

For artists, a world infused with agents (i.e. mythology) has always been an endless inspiration. As someone on the autistic spectrum, I’m not sure all these rich agents make the world more comprehensible, but the idea in the literature seems to be that most people more easily think in terms of social constructs, because of evolutionary reasons (importance of social intelligence for human survival) and lifetime learning. Predictably and pragmatically, social constructs have more power in our interaction with the animate world.

The theory of evolution is far from the only example of science creating discontent or alienation in people. Say, for example, we could scientifically explain love, would it be useful in daily life to have this explanation? To the contrary, probably. Say we would have the technology (based on solid science) to detect, based on micro-expressions or other physiological data, the true motivations of what someone says. A kind of lie detection on steroids. Would it improve our daily interactions? Again, to the contrary. Or think of depressive realism, the empirical finding that our judgments about own capacities or about the world are more truthful when we are depressed. It seems the lies or delusions are functional. Here a positively biased self-image can improve your self-image in the future, even though it is misrepresenting the present. I think science will keep on revealing these kinds of dynamics, and make human interaction more ‘calculating’ if we do not protect it somehow.

Hence, it’s no wonder that people are motivated to (and often succeed to) bracket the science by clenching to the fact that “there are still many things science cannot explain. There must be ‘more'”. Some will grab on to scientific ideas that seem deep and mysterious (eg popularity of ‘quantum’ ideas in new age milieu). Others will, as you say, embrace the true limitation principles (uncertainty, indeterminacy) that modern science has discovered. But this will not make them feel more at home in the world, nor will it replace the wonder and mystery lost because of a scientific worldview.

I appreciate [the] point that an agent-based approach (based on complex adaptive systems) can unify narrative and scientific worldviews, but that keeps the focus on fitness instead of concerns and aims people have, and the ethical value people can ascribe to the world. It introduces agents as fundamental units of reality, hence maybe making it more intuitive/friendly as a worldview for humans (as agents), but obscures two things: First … goals do not simply require equifinality but also work or effort (hence also the emotions associated with them). It follows that goal-directedness in the animate world cannot just be equated with ‘goals’ in the inanimate world (e.g. simple attractors). Second, there’s a disjoint between the conscious goals that humans can have and deal with (e.g. when we attach moral value to something), and the ‘goals’ that figure in scientific theories (e.g. fitness maximization, reward maximization, free energy minimization, etc.).

Science has the tendency to reduce (and explain away) human goals and concerns to other, more mechanistic ones (such as fitness, free energy,…), and rightly so. I suppose one can think of our conscious goals and concerns as part of our ‘user interface‘ allowing us to efficiently act in our (mostly social) world, but hiding the complexity and dynamics of the actual operations (similar to what icons, pointer, ‘desktop’, etc do on your computer). Something along these lines must be true, it seems to me, although this view threatens to undermine the autonomy of the (ethical) agent.

Note that I don’t think human, conscious goals and concerns are powerless or that they are not somehow actually represented and effective in our brain. Neither do I believe that when science succeeds in reducing them, it makes behavior easily predictable (cf. path-dependency and an enormous amount of minute differences that should be known to do this). However, their power crucially depends on assuming/asserting that they are irreducible, while science exactly emphasizes that they are reducible if they are ‘natural’. For example, we intrinsically value every human life irrespective of how ‘fit’ it is in the biological sense and irrespective of how conducive this idea of valuing human life is for the further continuation of the social system (other ideas might help the maintenance of a particular social system better).

To conclude … I suspect science cannot make up for much of the emotional lacuna (i.e. not limited mystery-related emotion) it created itself by displacing religious worldviews. I think this might boil down to a need for consolation for the human condition that science does not (and cannot, or so I’ve argued) have an answer to.

Art can do that, partly in the sense that … it can invoke (the possibility of) a richer, open-ended world. And in part, because it succeeds in (metaphorically) representing emotional dynamics that resonate with … embodied self-models and hence validate them, i.e. providing ‘sensory evidence’ for very individual emotional dynamics that often cannot even be articulated (see this brief comment I wrote about this). Art’s consoling powers derive from these two elements, namely, the suggestion of alternative paths (open-endedness) and the validation of core self-models. Your individual goals and concerns are no longer alien in such a world, but rather possible to be fulfilled. In other words, there is a prospect for progress relative to your concerns. That said, I’m not sure art (even if it is socially-experienced, as in musical performances) will be enough to console and make people make feel ‘at home in their world’ in a post-religious world.

Religion did/does a good job at making personal goals seem attainable in the face of adversity (e.g. by praying and other rituals; note that ‘seeming’ is enough to keep a man going), and at emphasizing common goals that are central, intrinsic to the world (‘pre-ordained by god’), hence not alien to it. The success of nationalism and other radical ideologies in an increasingly secularized world may suggest that ‘de-ideologized’ art isn’t enough to make people feel at home. However, secularization went together with individualization and commercialization in modern culture, so it is hard to trace the key cause(s) of discontent. Maybe improved secular well-being is possible if the latter, capitalist tendencies can be reined in, reestablishing the human-world by improved interpersonal instead of religious practices. I tend to think capitalist and scientific logic are tightly linked, but I like to dream otherwise …