Faith and Properly Basic Beliefs

Triumph of Faith over Idolatry by Jean-Baptiste Théodon (1646–1713)

Triumph of Faith over Idolatry by Jean-Baptiste Théodon (1646–1713)

A reader asked my opinion of this quote: “The function of faith is to take a basic belief and cloak it in the aura of a properly basic belief.” ~ Anonymous

Faith

Here I take the reader to be referring to religious faith, although faith more generally is trust or belief in a person, thing, or concept. Furthermore, religious faith itself is a concept with various meanings. For instance, it might refer to believing in spite of or without evidence, having sufficient warrant for one’s beliefs, experiencing a personal relationship with some (perceived) God, or simply having concern about humanity. It is also thought to exist in degrees such that faith may develop, grow, and/or deepen.

For this discussion, I’ll consider religious faith, at least among Christians, as having belief or trust in a religious person (God, Jesus), thing (heaven, prayer), or concept (soul, grace).

Properly Basic Beliefs

Properly basic beliefs (also called basic, foundational, or core beliefs) are, under the epistemological view called foundationalism, the axioms of a belief system. Foundationalism holds that all justified beliefs are either basic—they don’t depend upon other beliefs—or non-basic—they do derive from one or more basic beliefs.

In the philosophy of religion, reformed epistemology is a school of thought concerning the nature of knowledge as it applies to religious beliefs. Central to Reformed epistemology is the proposition that belief in God is “properly basic” and not need to be inferred from other truths to be rationally warranted.

Belief in God as Properly Basic

The philosopher/theologian most associated with this view is Alvin Plantinga. Basing his position on the theology of John Calvin he argues that we possess a special faculty or divine sense for knowing that God exists without any argument or evidence. As Plantinga puts it:

Calvin’s claim, then, is that God has created us in such a way that we have a strong tendency or inclination toward belief in him. This tendency has been in part overlaid or suppressed by sin. Were it not for the existence of sin in the world, human beings would believe in God to the same degree and with the same natural spontaneity that we believe in the existence of other persons, an external world, or the past. This is the natural human condition; it is because of our presently unnatural sinful condition that many find belief in God difficult or absurd. The fact is, Calvin thinks, one who does not believe in God is in an epistemically substandard position—rather like a man who does not believe that his wife exists, or thinks she is likely a cleverly constructed robot and has no thoughts, feelings, or consciousness. Although this belief in God is partially suppressed, it is nonetheless universally present. (Plantinga and Wolterstorff. Faith and Rationality. University of Notre Dame Press, 1983, pg. 66.)

Plantinga concludes that “there is a kind of faculty or cognitive mechanism, what Calvin calls sensus divinitatis or a sense of divinity, which in a wide variety of circumstances produces in us beliefs about God.” Thus belief in God is on par with other basic beliefs. According to Plantinga, properly basic beliefs include:

I see a tree (known perceptually),

I am in pain (known introspectively),

I had breakfast this morning (known through memory), and

God exists (known through the sensus divinitatis).

This Is One Of The Most Desperate and Frightening Arguments in the History of Philosophy

It’s hard to believe that anyone would find this argument convincing unless they were already firmly committed to believing in, or are fervently motivated to believe in, a God. First of all, the lack of theistic belief around the world undercuts the argument from a divine sense. Why then so many non-believers? Furthermore, people’s ideas of the nature of Gods vary substantially. Why then so many different conceptions? Second, if the Gods are so properly basic then why are they so hidden? Why century after century do they remain so silent, so absent?

Let me also say that I’m glad I didn’t study these arguments extensively. Becoming immersed in nonsense often gives it the aura of respectability. But does anyone really believe that the non-spatial, non-temporal God of classical theism—omnipotent, omniscience, omnibenevolent, immutable, etc.—is as basic as the other beliefs listed above? I’m sure some people would say yes, but why then is there infinitely more disagreement about the existence and nature of Gods than about the existence of trees and breakfast? I think even the Gods would be amused by this argument.

Finally, reformed epistemology is quite pernicious. Once you decide your privately held beliefs must be true and needn’t be justified by evidence available to all then I fear for what might follow. Believing one has a monopoly on truth has often led to disaster.

Back To The Quote

“The function of faith is to take a basic belief

and cloak it in the aura of a properly basic belief.”

I believe the quote has it about right. Here’s my explanation of how I think this works (psychologically.) You fervently believe something because it seems true, it comforts you, you want to believe it, your group believes it, etc. Then you dig in and hold on tenaciously. But at some point, you realize your beliefs could be mistaken. Then you look for an intellectual defense to bolster your emotionally held beliefs, to defend them against outsiders. In your search, you happen to discover Christian reformed epistemology, finding that your beliefs are axiomatic or properly basic. No need for evidence, problem solved!

So the encounter with the intellectual argument augments one’s faith or belief. You begin with the belief, look for supporting reasons and then, not surprisingly, you find them. (For more see “Psychological Impediments to Good Thinking.”) Finding what seem to be good reasons further bolsters the faith. So faith makes you more receptive to viewing your beliefs as properly basic, and viewing your beliefs as properly basic bolsters your faith. They are a feedback loop. Faith is the water in which all this swims and in its absence, an argument that your beliefs are basic will never be convincing.

Psychological Explanations

Of course, you can provide a psychological explanation of mine or anyone’s beliefs. Perhaps my natural psychological tendencies lean toward being skeptical, questioning authority, wanting intellectual explanations, etc. This, in turn, was exacerbated by a scientific and philosophical education and other environmental factors. If all this is true then our beliefs simply reflect the combination of our nature and nurture. But this isn’t completely right either. Some ideas are true independent of people because they are more robust, more predictive, more consistent with the evidence, ie., more likely to be true. These are the well-confirmed ideas of modern science. All beliefs are not created equal.

Final Thoughts

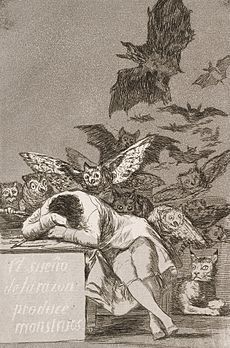

In the end, I’m an evidentialist—the evidence is of primary importance to me regarding belief. But defenders of reformed epistemology say that they don’t need evidence for something properly basic because it’s axiomatic just like a = a, or triangles having 3 sides. But to me, this seems wildly implausible. And I shiver at the thought of those who defend controversially beliefs by essentially saying, “my belief in God is just like your belief that there is a table in front of you.” This is someone you cannot reason with and, as the Spanish painter, Francisco Goya so aptly put it. “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters.”

Francisco Goyo, “El sueño de la razón produce monstruos”